Our work so far has transformed the way we prevent and respond to family violence. However, we have not yet delivered the full extent of the vision of the Royal Commission into Family Violence (the Royal Commission).

We are only part-way through our plan. Our work needs time to take effect.

We know we must continue with this unfinished business.

Many Victorians continue to use violence against intimate partners and family members. This violence cuts lives short and causes lifelong harm.

It also places an enormous burden on our economy.

We simply cannot afford to step back from this challenge.

We need to disrupt the cycle of family violence. If we don’t, the costs to people’s lives will continue to be devastating and the costs to the economy will be unsustainable.

How many people are being harmed by family violence in Victoria now?

- 92,296 family violence incidents were reported [1]

- 41% of recorded sexual offences related to family violence [2]

- 66,309 individuals or families were referred for support through The Orange Door network [3]

Who experiences family violence?

Violence against people of different ages

From July 2021 to June 2022 in Victoria:

- 5,258 family violence incidents were perpetrated against a person aged 65 or older [4]

- 33,240 family violence incidents had children present [5]

- 34,437 referrals to The Orange Door network included at least one child [3]

The gendered nature of family violence

From July 2021 to June 2022 in Victoria:

- 73% of people who were reported as perpetrators of family violence were male [6]

- 71% of people who had family violence perpetrated against them were female [4]

- 61% of children who had family violence perpetrated against them were girls [4]

- 63% of people over the age of 65 who had family violence perpetrated against them were women [4]

Violence against Aboriginal women and children

Family violence is not part of Aboriginal culture or Aboriginal identity. However, it has a disproportionate impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Victoria. This is particularly the case for women and children.

This impact is the same whether Aboriginal people live in rural, regional or urban areas.

A significant proportion of family violence and violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and children is perpetrated by non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men from many cultural backgrounds [7].

Family violence also contributes to the increasing criminalisation of Aboriginal women in Victoria. This is because a significant proportion of Aboriginal women in prison have experienced family violence or sexual abuse [8].

Aboriginal women are:

- 45 times more likely to experience family violence than non-Aboriginal women [9]

- 25 times more likely to be killed or injured from family violence than non-Aboriginal women [9]

Experiences of violence across our community

Particular communities face a greater risk of family violence. They include multicultural and multifaith communities, LGBTIQ+ communities, people with a disability, sex workers and women in or exiting prison.

Together with people living in rural and regional areas, these groups may also face barriers when they seek help. This is because their experiences of family violence may be less visible and less well understood [10].

When people identify with more than one of these communities, the risks and challenges can be heightened.

- Women with disability are almost 2 times more likely to experience physical or sexual violence from a partner than women without disability [11]

- 43% of LGBTIQ+ Victorians have been abused by an intimate partner [12]

- 70-90% of women in custody have experienced abuse [13]

- 38% of LGBTIQ+ Victorians have been abused by a family member [13]

- The Orange Door network has provided support to 141,565 people in regional/rural areas since 2018

- Women from refugee backgrounds are particularly vulnerable to financial abuse, reproductive coercion and immigration-related violence [14]

Is family violence decreasing in Victoria?

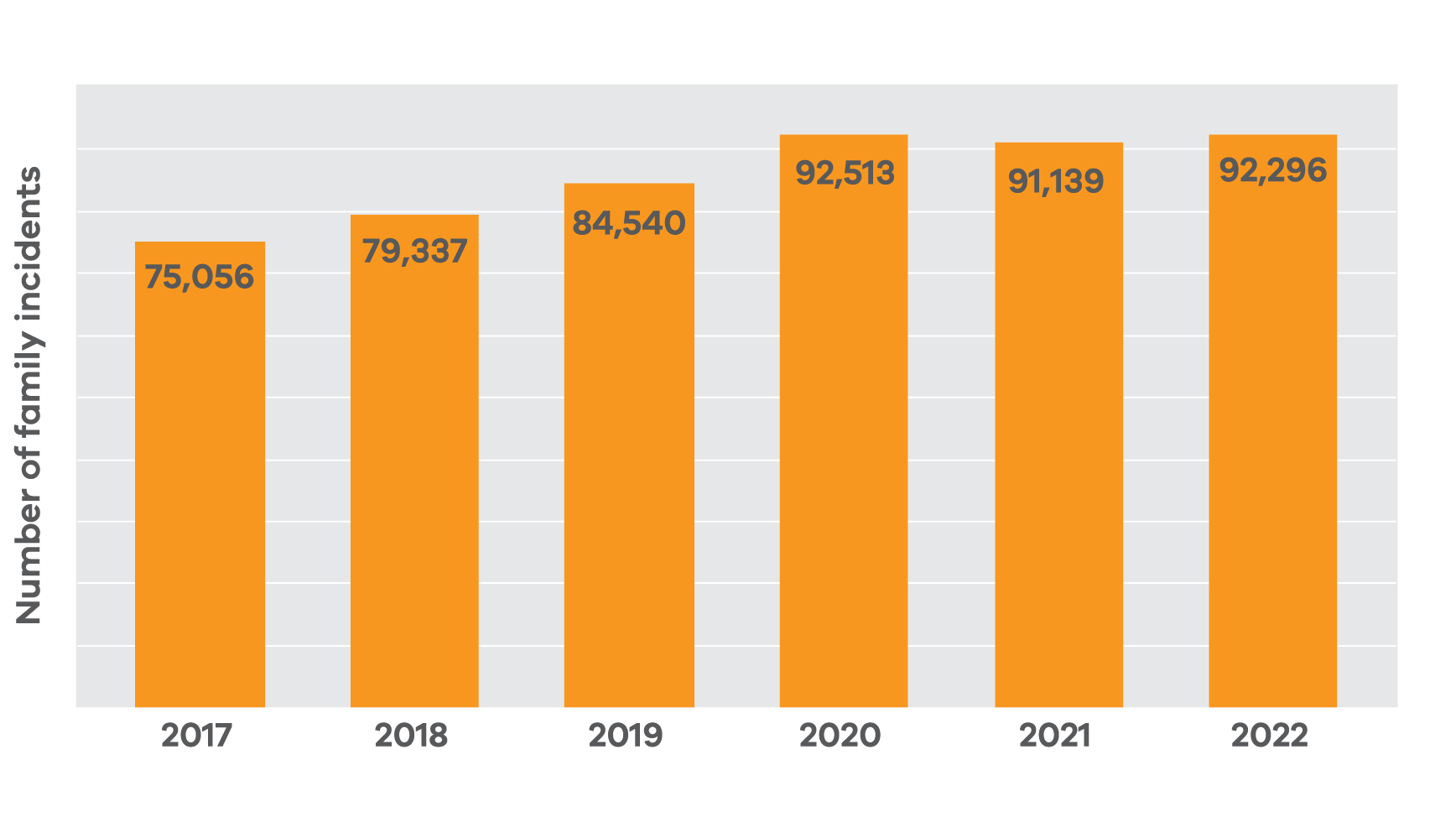

Reports of family violence to police appear to have stabilised in recent years. However, we do not yet know if family violence has peaked.

This is because many people do not report their experience of family violence to police or seek any help.

In fact, more than a third of people who have experienced physical violence [15], and half of those who have experienced sexual assault, have not yet sought help [16].

After the Royal Commission, we set out to reduce this gap between the number of family violence incidents in Victoria and how many of those are reported. We worked to increase people’s understanding of family violence, so it was easier to identify. We strengthened the way we respond to family violence so more people would feel confident to report it or seek help.

Success would mean reports would increase at first and this is exactly what happened. Reports of family violence steadily increased in the early years of Ending family violence: Victoria's 10-year plan for change.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have also contributed to this increase. Family violence workers reported that, during the pandemic, there were more first-time reports of family violence, and those reports were more likely to involve severe violence [17].

Reports of family violence now look like they are levelling off. However, they are 23 per cent higher than they were in 2017. Reports have increased from 75,056 in 2017 [18] to 92,296 in 2022 [19].

We do not yet have all the data we need to truly understand the extent of family violence in the community.

While we work to build this data, we will continue to focus on reducing the gap between prevalence and reporting so we can be confident no one is left behind as rates of violence fall.

We are also doing ground-breaking work to see if we can predict when family violence will peak and then decline in Victoria.

References

[1] CSA (Crime Statistics Agency) 2023a, Key figures: year ending December 2022, accessed 7 June 2023.

[2] CSA (Crime Statistics Agency) 2022a, Victoria Police data tables (2021–2022): Table 21. Offences recorded by offence categories and family incident flag, July 2017 to June 2022, accessed 4 July 2023.

[3] Family Safety Victoria 2022, The Orange Door annual service delivery report 2020–21: referrals and access, State of Victoria, accessed 26 June 2023.

[4] CSA Crime Statistics Agency) 2022b, Victoria Police data tables (2021–2022): Table 4 Affected family members by sex and age July 2017 to June 2022, accessed 1 August 2023.

[5] CSA (Crime Statistics Agency) 2023b, Family incidents: T1 family incidents recorded and rate per 100,000 population, accessed 9 June 2023.

[6] CSA (Crime Statistics Agency) 2022c, Victoria Police data tables (2021–2022): Table 6 Other parties by sex and age July 2017 to June 2022, accessed 8 June 2023.

[7] Our Watch 2023, Challenging misconceptions about violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, accessed 7 June 2023.

[8] VEOHRC (Victorian Equal Opportunities and Human Rights Commission) 2013, Unfinished business: Koori women and the justice system, State of Victoria, accessed 26 June 2023

[9] State of Victoria 2021a, Family violence reform rolling action plan 2020–2023: Aboriginal self-determination, accessed 7 June 2023.

[10] State of Victoria 2021b, Everybody matters: inclusion and equity statement, accessed 20 June 2023.

[11] People with Disability Australia and Domestic Violence NSW (PWDA and DVNSW) 2021, Women with disability and domestic and family violence: a guide for policy and practice, accessed 22 June 2023.

[12] Department of Families, Fairness and Housing 2022, Pride in our future: Victoria’s LGBTIQ+ strategy 2022–32, State of Victoria.

[13] ANROWS (Australian National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety) 2020, Women’s imprisonment and domestic, family, and sexual violence: research synthesis, accessed 22 June 2023.

[14] AIFS (Australian Institute of Family Studies) 2018, Intimate partner violence in Australian refugee communities, accessed 22 June 2023.

[15] AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2022a, Family, domestic and sexual violence data in Australia, accessed 7 June 2023

[16] AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2020 Sexual assault in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 7 June 2023.

[17] Pfitzner N, Fitz-Gibbon K and True J 2020, Responding to the ‘shadow pandemics’: practitioner views on the nature of and responses to violence against women in Victoria, Australia during the COVID-19 restrictions.

[18] CSA (Crime Statistics Agency) 2016, Predictor of recidivism amongst police recorded family violence perpetrators.

[19] CSA (Crime Statistics Agency) 2023c, Family incidents, accessed 7 June 2023.

Updated