Indicator: Increased awareness of what constitutes violence

Being able to identify violence is critical, as it can prompt people to seek help or report if they have, or someone they know has, experienced domestic violence, sexual assault, harassment or other forms of violence. Understanding that violence includes a range of behaviours, including non-physical forms of violence, such as emotional, financial or technology-facilitated abuse, can contribute to a shift in attitudes that condone or minimise these types of violence.

This indicator provides insights into the level of understanding of what domestic violence and violence against women looks like, and whether advocacy and awareness raising efforts are having an impact.

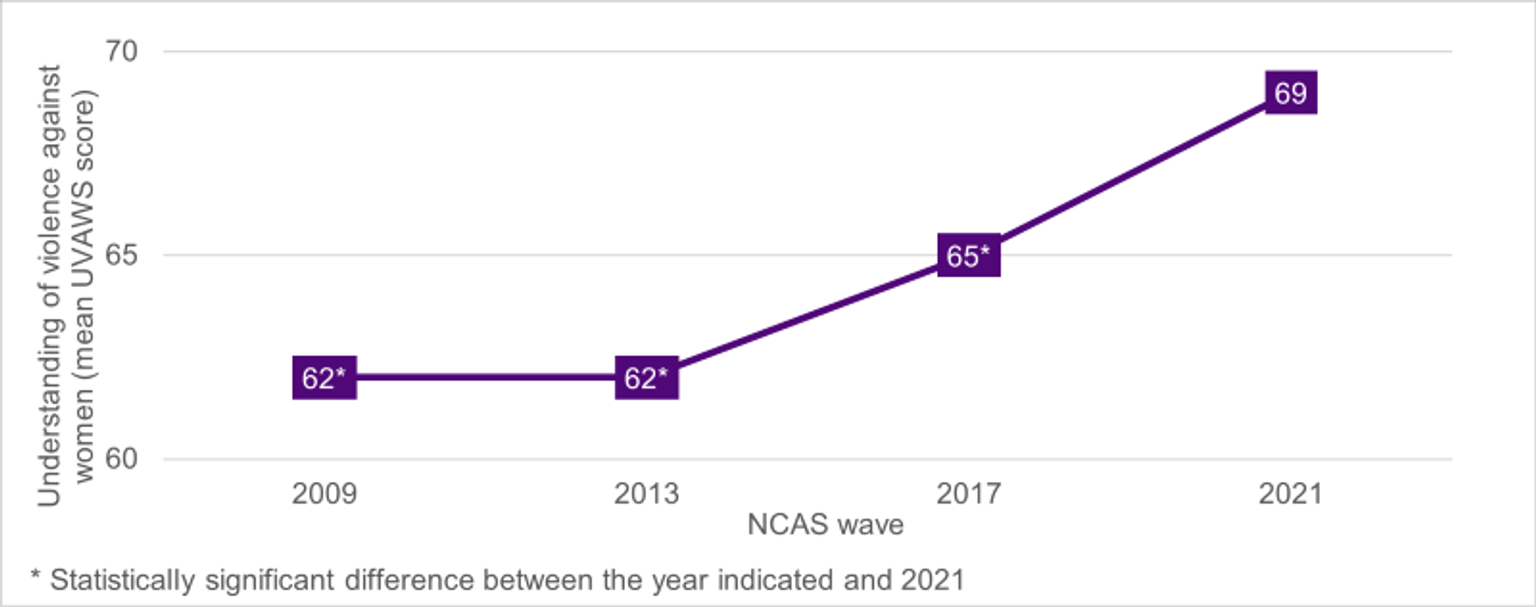

Measure: Victorian mean score on the Understanding of Violence Against Women Scale (UVAWS)

The Understanding of Violence Against Women Scale (UVAWS) examines whether people recognise the range of violent, abusive, and controlling behaviours as domestic violence and violence against women, and that men are the main perpetrators of this violence.

Figure 1 shows that Victoria had a significantly higher mean UVAWS score in 2021 compared with 2009, 2013 and 2017. This finding indicates a significant increase over time in Victorians’ understanding of violence against women.

UVAWS subscale scores indicate an improvement in Victorians’ understanding of the different behaviours that constitute domestic violence and violence against women more broadly. Both the subscales scores for ‘Recognise violence against women’ (68) and ‘Recognise domestic violence’ (69) were significantly higher for Victoria in 2021 compared to all previous years.

Despite these improvements, 39 per cent of Victorians still believe domestic violence was perpetrated by men and women equally in 2021. This is despite Personal Safety Survey, police and court data clearly showing that most perpetrators are men, and most victims and victim survivors are women.

This suggests Victorians, like Australians more broadly, are generally better at recognising behaviours that constitute domestic violence than they are at understanding that domestic violence is highly gendered in that it is disproportionately perpetrated by men against women.

Indicator: Decrease in attitudes that justify, excuse, minimise, hide or shift blame for violence

This indicator relates to condoning violence against women, which is one of the four gendered drivers of family violence and violence against women identified in Change the story.

Violence against women can be condoned or excused through social attitudes and norms, practices or structures. For example:

- justifying violence against women on the basis that it is acceptable for men to use violence in certain circumstances

- excusing violence by attributing it to external factors or implying that men cannot be held fully responsible for their own behaviour

- trivialising violence based on the perception that its impacts are not serious enough to warrant action

- downplaying violence by denying it seriousness, that it occurs or denying that certain behaviours constitute violence

- shifting blame for the violence from the perpetrator to the victim.

This indicator is important to monitor, because evidence indicates that when societies, institutions, communities or individuals support or condone violence against women, the prevalence of violence is higher.1 Men who hold these beliefs are more likely to perpetrate violence against women, and both women and men who hold these beliefs are less likely to support victims and hold perpetrators to account.2

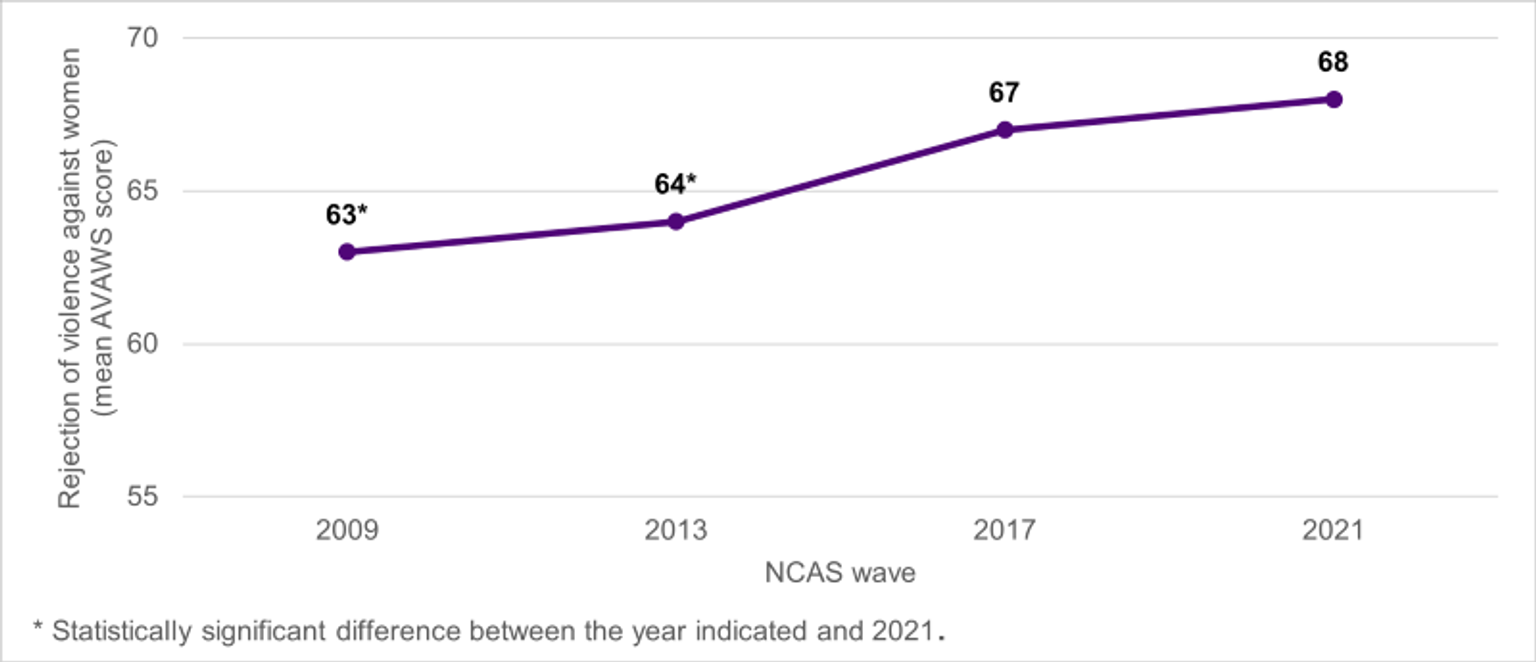

Measure: Victorian mean score on the Attitudes towards Violence Against Women Scale (AVAWS)

The Attitudes towards Violence against Women Scale3 (AVAWS) measures the rejection of problematic attitudes regarding violence against women. These include attitudes that minimise violence against women, distrust women’s reports of violence, and objectify women or disregard consent.

The mean AVAWS score for Victoria was significantly higher in 2021 than it was in 2009 and 2013. This indicates a significant increase over time in attitudes that reject violence against women (Figure 2). However, like the rest of Australia, no significant increase in AVAWS scores was observed in Victoria between 2017 and 2021. This was largely due to a plateau in attitudinal rejection of domestic violence; Victorians’ rejection of sexual violence did significantly improve between these years.

There were improvements over time on two of the AVAWS subscales for Victoria:

- the ‘Mistrust women’ subscale indicated increased rejection of attitudes that women lie about being victimised to gain some advantage (68 per cent in 2021 compared with 66 per cent 2017; this scale was not included in the 2009 and 2013 survey)

- the ‘Minimise violence’ subscale indicated increased rejection over the longer term of attitudes that downplay the seriousness of violence and shift blame to victims and survivors (from 65 per cent in 2009 to 69 per cent in 2021). However, this rejection plateaued between 2017 and 2021, with no statistically significant change between these years.

There was no significant improvement in Victoria on the ‘Objectify women’ subscale between 2017 and 2021. The ‘Objectify women’ subscale measures attitudes that objectify women and disregard consent. This does not necessarily mean that Victoria is lagging behind other jurisdictions. Instead, it indicates Victoria progressed more slowly compared to the national average on those subscales between 2017 and 2021.

These results are a reminder that changing the deeply held attitudes that allow violence to occur is not easy. It is complex, long-term work that requires dedicated focus, investment and effort across the community.

Footnotes

1 European Commission 2010, Factors at play in the perpetration of violence against women, violence against children and sexual orientation violence: A multi-level interactive model. European Commission, Brussels. https://www.humanconsultancy.com/assets/factor-model-en/index.html

2 Heise L 2011, What works to prevent partner violence: an evidence overview. Department for International Development, United Kingdom. https://www.oecd.org/derec/49872444.pdf

3 Note that the wording of this scale in the NCAS has changed since the publication of the Family Violence Outcomes Framework implementation strategy, and the measure here has been adjusted to reflect this.

Updated