- Date:

- 29 Dec 2023

Foreword from the Minister for Prevention of Family Violence, Minister Vicki Ward

I’m pleased to present the Ending family violence annual report, which documents the crucial work done across government to prevent and respond to family violence in Victoria.

It’s been seven years since the Royal Commission into family violence handed down its final report. We committed to implement all 227 of its recommendations and began the task of building a new, stronger and more coordinated family violence system.

And we did it - in 2022, we implemented the final 23 of those 227 recommendations. It’s been a period of fast-paced whole-scale change funded by an investment of more than $3.86 billion and led by many dedicated individuals and organisations across Victoria, a huge achievement.

During 2022, five more Orange Doors opened, completing the state-wide rollout of The Orange Door network, along with the opening of four new specialist refuges and expansion of the Central Information Point. Legislative amendments were passed supporting victim survivors of family violence giving evidence and seven additional courts in the Specialist Family Violence Court Division started operations.

It is all wonderful progress, but the work needs to go on.

So, we are keeping the focus on Ending family violence, our 10-year plan, guided by the current Family Violence Reform Rolling Action Plan 2020-2023. I’m pleased to note that we are on track to complete most of the remaining activities outlined in the plan, driving the next phase of reform and creating a system that is more connected, sustainable and delivering better outcomes for victim survivors.

We committed to ending family violence here in Victoria. We knew it wouldn’t be easy and we knew it would take generations, but it has to be done.

The Ending family violence annual report shows how far we’ve come and reveals the sobering truths about just how far we still have to go. It shows how we are continuing our work to build a nation-leading family violence system, with transparency and accountability.

Acknowledgments

Content warning

This document contains reference to and descriptions of acts of family and sexual violence.

If you have experienced violence or sexual assault and need immediate or ongoing help, contact 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) to talk to a counsellor from the national sexual assault and domestic violence hotline. For confidential support and information, contact Safe Steps’ 24/7 family violence response line on 1800 015 188.

If you have concerns about your safety or that of someone else, please contact the police in your state or territory, or call Triple Zero (000) for emergency help.

Our commitment to end family violence

The 2015 Royal Commission into Family Violence (Royal Commission) highlighted the devastating prevalence and impact of family violence across Victoria. Family violence cuts lives short, inflicts significant harm, and creates cycles of intergenerational trauma and violence.

Our vision is a future where all Victorians are safe, thriving and live free from family violence. Ending family violence: Victoria’s plan for change is our 10-year plan to work towards this vision.

It laid the foundation for a period of fast-paced change, backed with investment of more than $3.86 billion since 2016. The Victorian Government has now implemented all 227 of the Royal Commission’s recommendations. However, we remain focused on our 10-year plan. We are implementing it through a series of three consecutive action plans. Our current work is guided by the second Family violence reform: rolling action plan 2020–23.

About this report

This report outlines the key actions undertaken by the Victorian Government in 2022 to implement the 10-year plan and the second Rolling action plan. It does not capture the full breadth and depth of work undertaken by the family violence sector across Victoria, nor its many achievements over the past year.

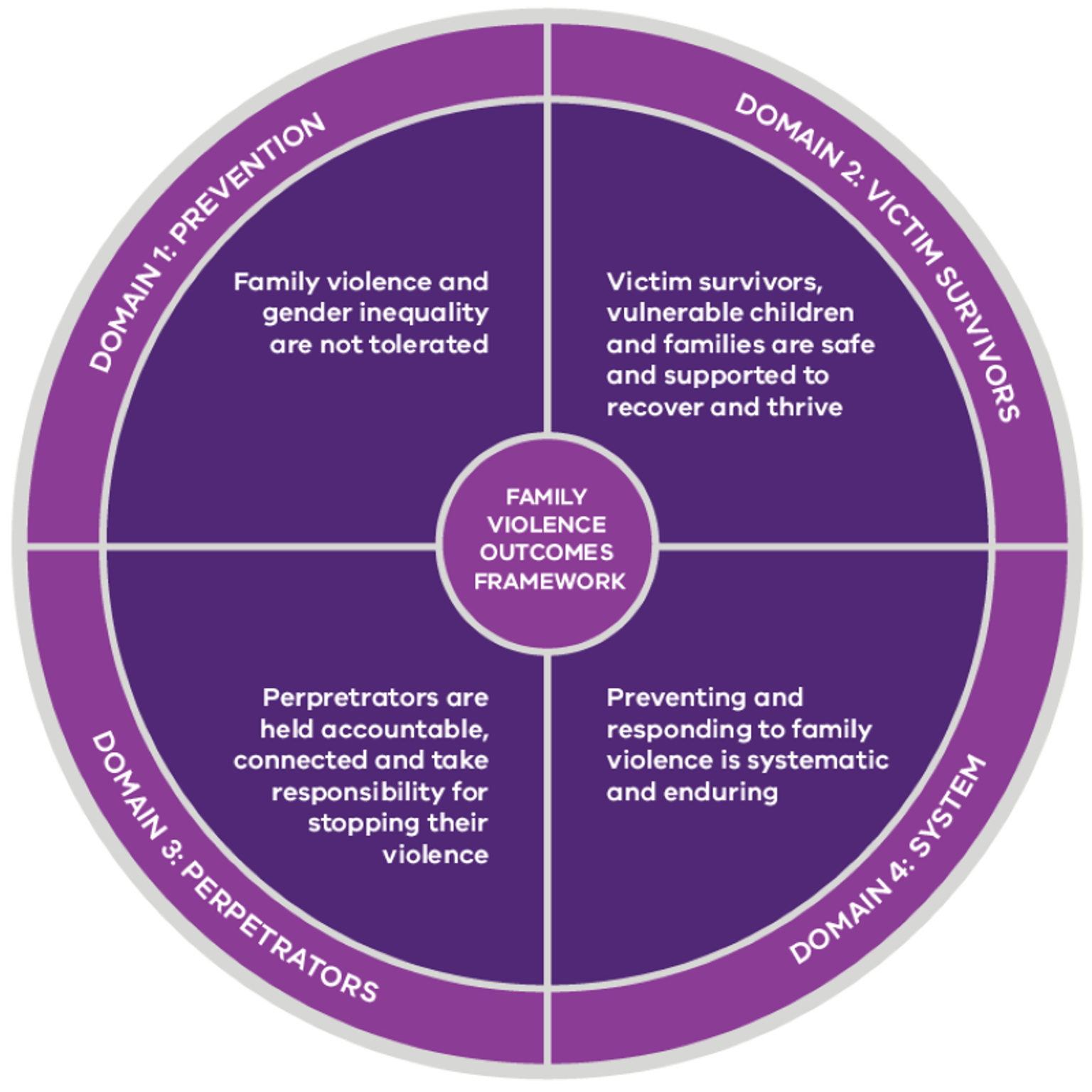

The report also includes an annual update on the outcomes of our efforts. We use the Family Violence Outcomes Framework to monitor progress towards our goals.

The Victorian Government acknowledges and thanks every person who works to prevent and respond to family violence across our state. We acknowledge the tireless efforts of the family violence sector, which designs and delivers nation-leading primary prevention initiatives and frontline services, and provides expert advice to government, including through the Family Violence Reform Advisory Group.

We acknowledge our enduring partnership with Aboriginal people and organisations through the Dhelk Dja Partnership Agreement and reaffirm our commitment to self-determination.

The lived experience of victim survivors is at the heart of this. We acknowledge their resilience, diversity and powerful insights that help guide our efforts, including through the formal advice we receive from the Victim Survivors Advisory Council.

Previous reports

A future where all Victorians are safe, thriving and live free from family violence

The Victorian Government has delivered on its commitment to implement all 227 recommendations of the Royal Commission into Family Violence.

In 2022, we passed a significant milestone on the path towards a Victoria free from family violence: the implementation of the final 23 recommendations of the Royal Commission.

This achievement is the result of more than six years of dedication, investment and collaboration across government and the family violence sector.

To implement these remaining recommendations in 2022, we:

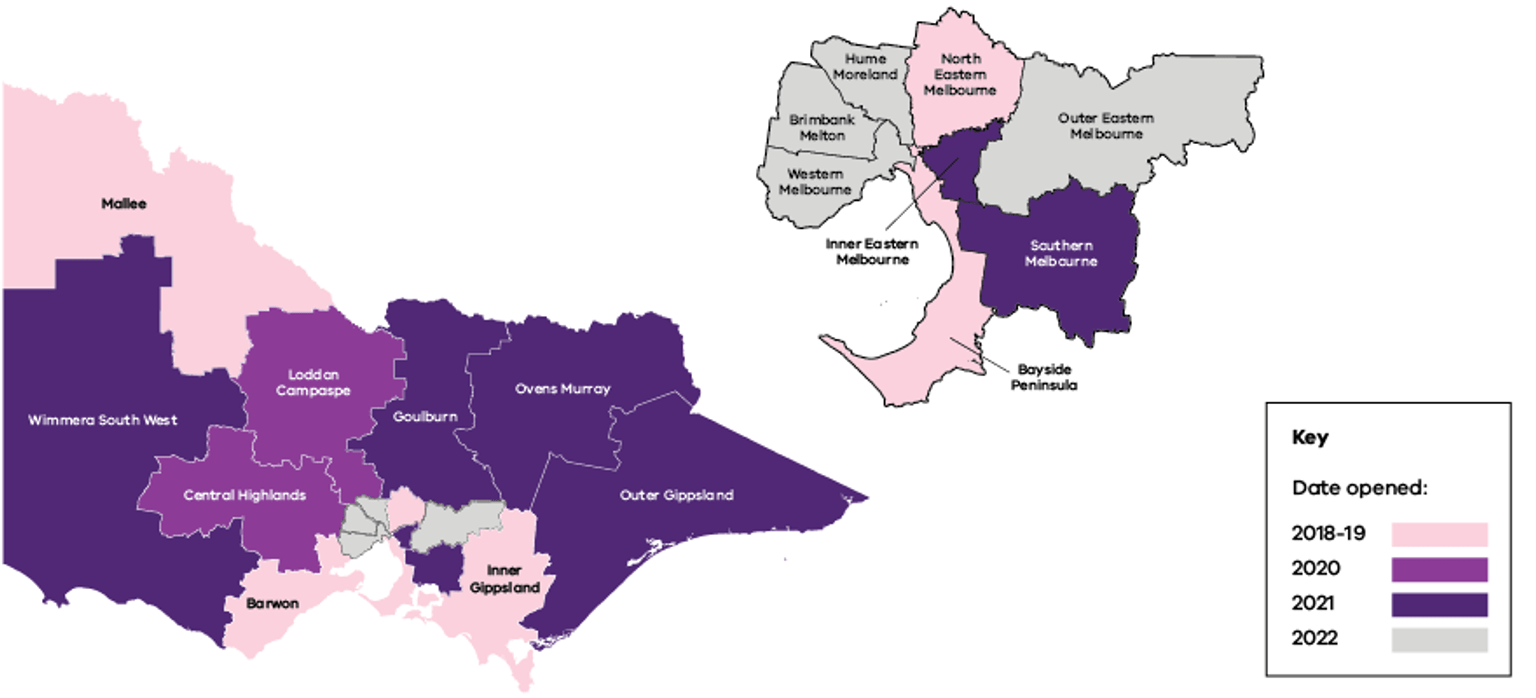

- opened five Orange Doors to complete the statewide rollout of The Orange Door network across Victoria. This network brings services together in accessible locations to support people affected by family violence.

- established an additional seven Specialist Family Violence Courts, bringing the total number to 12 sites operating across Victoria at the end of 2022. The facilities and services at these courts make the court experience safer and more responsive to the communities needs.

- passed amendments to the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 and the Criminal Procedure Act 2009 to enable victim survivors of family violence to give evidence from a place other than the courtroom. This keeps victim survivors safe by minimising the potential for further trauma and avoiding direct contact with perpetrators during court proceedings. The change is being embedded through the Remote Hearing Support Service, which became available for family violence hearings at 11 Victorian Magistrates’ Court locations in 2022.

- opened four core and cluster refuges. These provide safe and private independent unit accommodation for victim survivors. Fourteen core and cluster refuges are now operational.

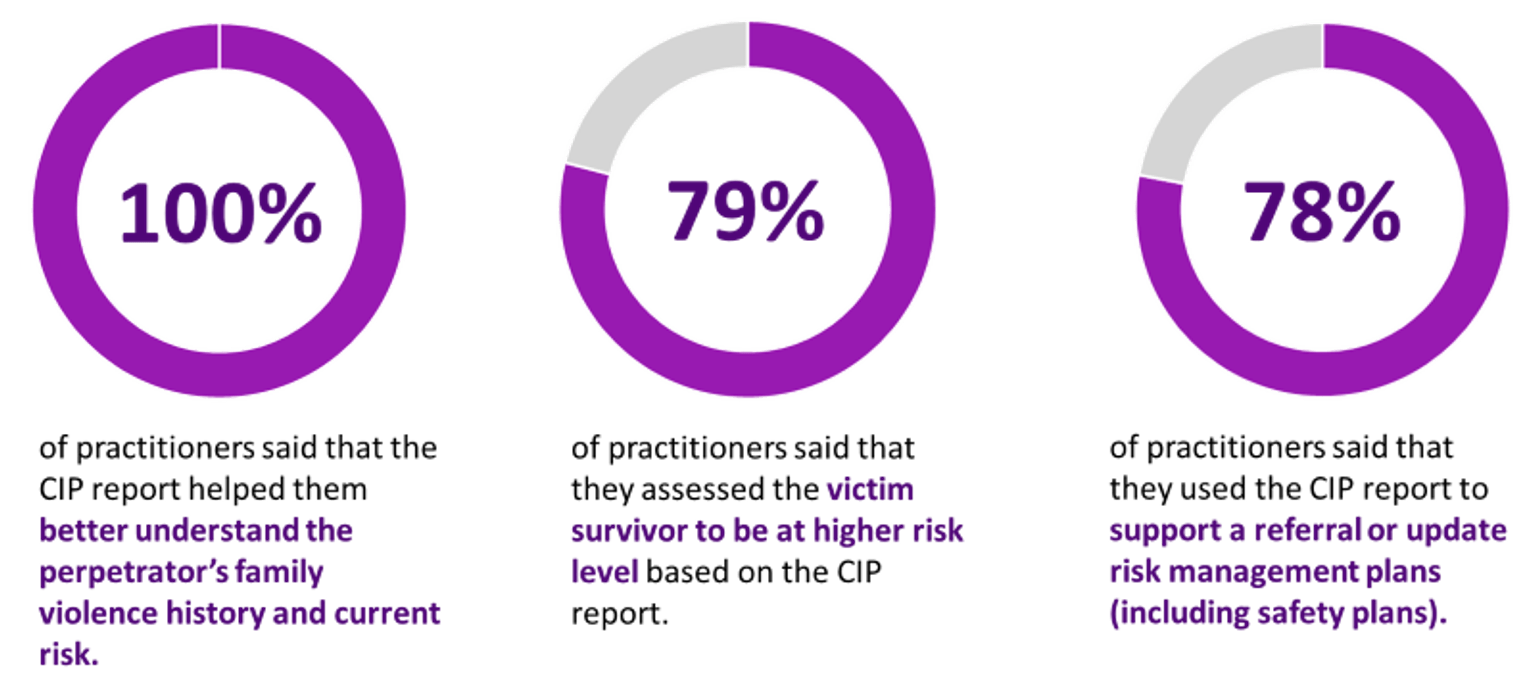

- expanded the Central Information Point (CIP) to Safe Steps and the Men’s Referral Service. This enables these services to share information about a perpetrator or alleged perpetrator which is compiled into a consolidated report to assist with family violence risk assessment and management. The work builds on the implementation of CIP for The Orange Door network from 2018 to 2022, and for the Risk Assessment and Management Panels from 2020 to 2022.

Is family violence decreasing in Victoria?

After the Royal Commission, we set out to reduce the gap between the number of family violence incidents in Victoria and how many of those are reported to police. We have had some success in doing this.

Reports of family violence steadily increased in the early years of our 10-year plan. This is in part because our reforms made it easier for people to identify family violence, report it and seek help. The COVID-19 pandemic may also have contributed to this increase. Family violence workers reported more first-time reports of family violence during the pandemic.1

In addition, our reforms mean police are more responsive to the complexity of family violence. More perpetrators are being reported and sentenced for breaching family violence orders, including against former partners.2

We have strengthened the system so that victim survivors now have more entry points to seek help, including through Victoria Police, The Orange Door network and Safe Steps. Client surveys show an 86 per cent satisfaction rate with The Orange Door services.3 The Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor reported that victim survivors’ experiences with the family violence system are more positive compared with the pre-reform period.4

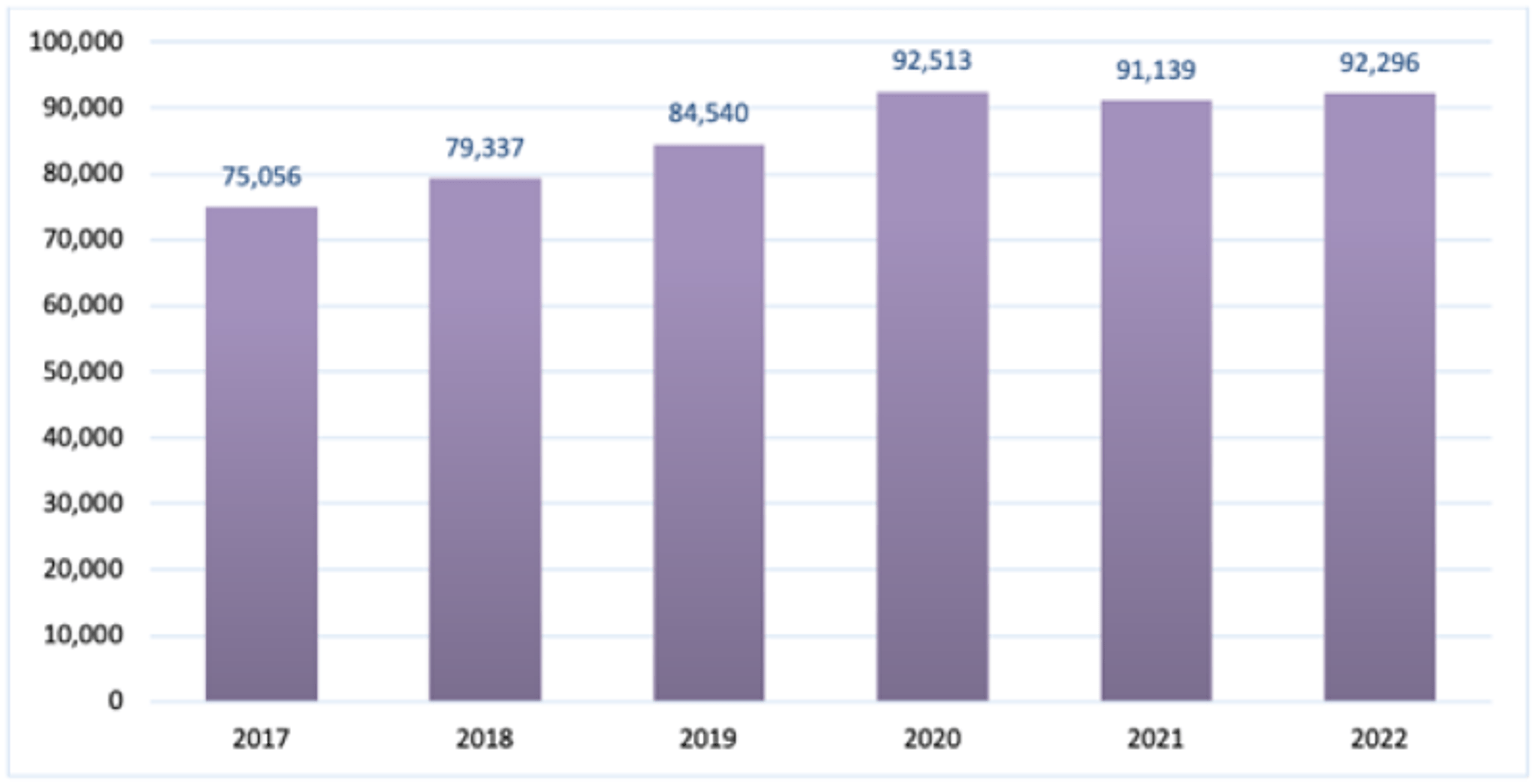

Reports of family violence appear to be plateauing, but they remain 23 per cent higher than in 2017, having increased from 75,056 reports in 2017 to 92,296 reports in 2022.

We do not yet have all the data we need to fully understand the extent of family violence in the community, especially how it affects specific groups and communities. While we build this data capability, we will focus on reducing the gap between prevalence and reporting so we do not leave anyone behind.

Footnotes

1 Pfitzner N, Fitz-Gibbon K and Tru J 2022, ‘When staying home isn’t safe: Australian practitioner experiences of responding to intimate partner violence during COVID-19 restrictions’. Journal of Gender-Based Violence. DOI:10.1332/239868021X16420024310873.

2 Sentencing Advisory Council 2022, Sentencing breaches of family violence intervention orders and safety notices, Third Monitoring Report, pp. 4, 18–20. https://www.sentencingcouncil.vic.gov.au/publications/sentencing-breach…

3 Department of Families, Fairness and Housing 2022, Annual report 2021–22, p. 52. https://www.dffh.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/202209/FINAL%…

4 Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor 2022, Crisis response to recovery model for victim survivors, December 2022, p. i. https://www.fvrim.vic.gov.au/monitoring-victorias-family-violence-refor…

The Rolling Action Plan 2020–2023

The Rolling action plan 2020–2023 is our second rolling action plan under the Ending family violence: Victoria’s 10-year plan.

Its purpose is to focus our efforts and investment as we work towards a Victoria free from family violence.

It does this by setting out 10 specific priorities for the period of the plan and reaffirming our commitment to three reform-wide priorities. These are discussed in the ‘Our progress against the Rolling action plan’ section that follows.

The 10 specific priorities are:

- reforming the way courts respond to family violence

- implementing Dhelk Dja: Safe our way – a 10-year agreement for the delivery of family violence services for Aboriginal Victorians

- providing access to safe, secure and stable housing

- improving legal assistance access, representation and integration across the family violence system

- putting in place the MARAM and information sharing frameworks to provide a shared approach to family violence risk assessment and management across justice, community, education and health

- creating a system-wide approach to create an effective web of accountability for perpetrators and people who use violence

- effecting long-term behavioural change through primary prevention to stop family violence before it starts

- coordinating research and evaluation across the family violence reform

- delivering The Orange Door network – an accessible and visible service for people experiencing family violence and children and families in need of support

- the development of a dynamic, collaborative and specialist family violence workforce based on Building from strength: 10-year industry plan

The Rolling action plan highlights two additional themes:

- Children and young people – the Rolling action plan recognises that children and young people are victim survivors in their own right with their own distinct needs. It sets out the tailored support children and young people need to be safe and recover from family violence.

- Sexual assault and family violence – the Rolling action plan recognises that sexual violence, abuse and harm share the same origins in gender inequality as other forms of family violence. and outlines how the family violence system is responding to sexual assault.

Each of these themes is considered across the delivery of all areas of family violence reform.

Our progress against the Rolling action plan 2020-2023

We committed to 209 activities in the second Rolling action plan. At the end of 2022:

- 121 (58 per cent) are complete, up from 40 in 2021. This includes ongoing activities that are now under way

- 82 (39 per cent) are in progress, with most of these on track to be completed in 2023

- 6 (3 per cent) are in progress but have experienced delays.

Download

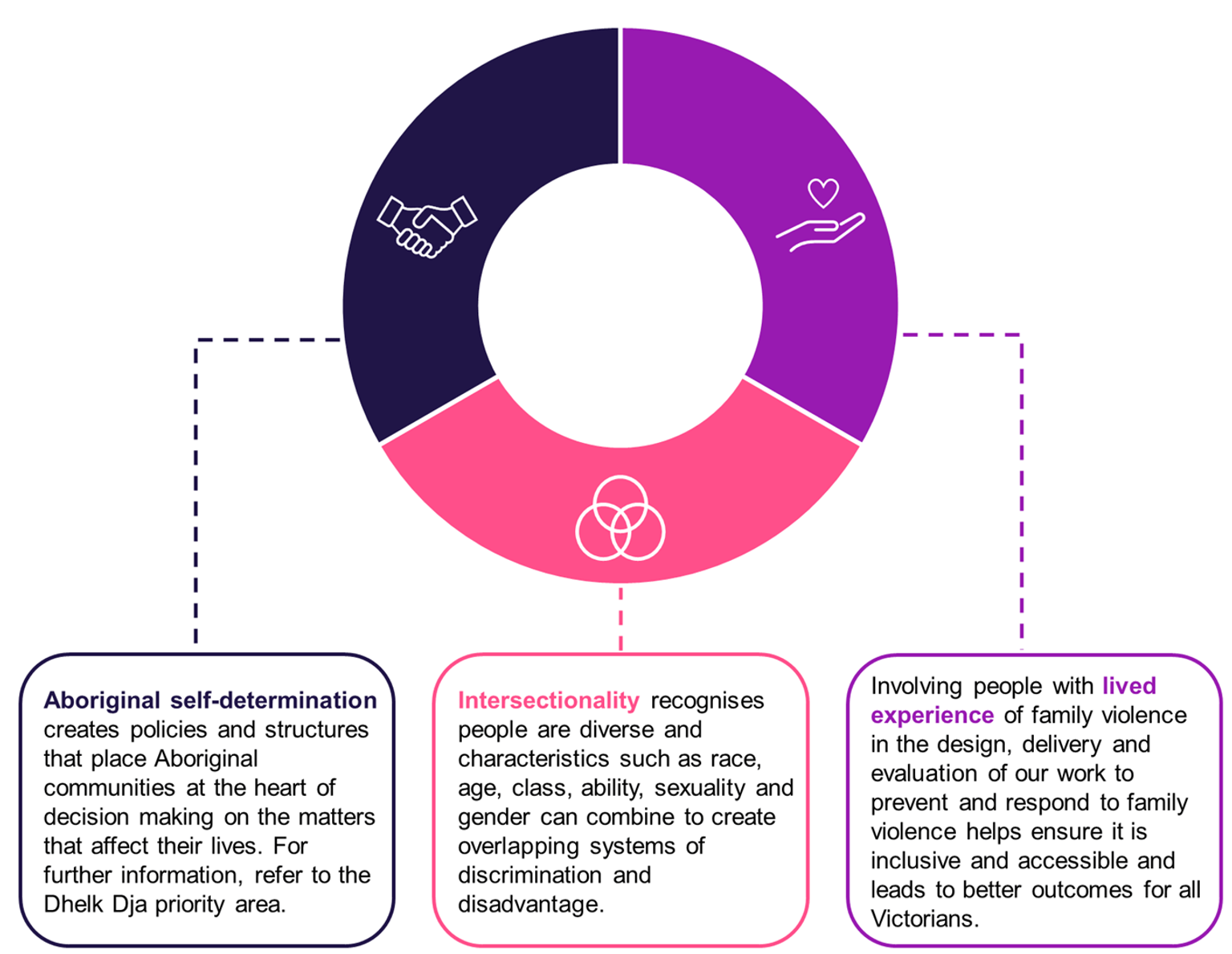

The following sections highlight key actions taken in 2022 in relation to:

- the reform-wide priorities of lived experience and intersectionality (Aboriginal self-determination is addressed under the priority relating to Dhelk Dja: Safe our way)

- the additional themes of sexual assault and children and young people

- the 10 specific priorities under the Rolling action plan.

Reform-wide priorities

Lived experience

- The Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council introduced seven new members in October 2022. It co-designed the Lived experience strategy and the online forum More than our story: Action, wisdom and change.

- The Lived Experience Strategy sets out clear priorities and actions to create more opportunities for people with lived experience to lead and influence the implementation of the family violence reform.

Intersectionality

- As part of the Intersectionality Capacity Building Project, we piloted and released resources to equip family violence and universal service workforces to embed an intersectional approach across family violence, sexual assault, and child and family services.

- Through the LGBTIQ+ Family Violence Capacity Building Initiative, we continued to build the capacity of specialist family violence workers to provide appropriate support and resources for LGBTIQ+ communities. Key achievements include the development of the Inclusive refuge guide and the roll out of LGBTIQ+ inclusion training to sexual assault services.

Additional themes

Children and young people

- Approximately 3,000 therapeutic services were provided to children to support their healing and recovery from family violence. These included services such as child–parent attachment therapy for children under five, and play, art and music therapies.

- The Adolescent Family Violence in the Home program was expanded across the state. The program delivers a new early intervention model of care for young people aged 12 to 17 years who use violence and their families, to reduce violence in the home and increase the safety of impacted family members. Approximately 1,040 children and young people, and their families, participate in the program each year, including 170 Aboriginal families.

- We funded the Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare to develop eight practice guides to support workers across The Orange Door network and the broader sector to engage more effectively with children and young people in their own right.

- Monash University was funded to deliver a lived experience research project to inform the development of the Child and young-person-focused MARAM practice guides and tools. The I believe you report report was published in 2023. It presents findings from 17 in-depth interviews conducted with Victorian children and young people, aged 10 to 25, with lived experience of family violence.

Sexual assault

- 15,788 sexual assault support services were provided to victim survivors of recent and past sexual assault, including children and young people. These services included immediate crisis support such as counselling, advocacy, and liaison with Child Protection as well as long-term therapies to support healing and recovery.

- We upgraded the statewide Sexual Assault Crisis Line delivered by Sexual Assault Services Victoria. This upgrade will provide an improved service for victim survivors of sexual assault, enhance record-keeping and provide a web-based chat option.

Courts

Reforming the courts response to family violence

We are transforming the court system to make it safer and more accessible for all people affected by family violence, including children and young people. Courts are also working to increase the accountability of people who use violence and encourage them to change their behaviour.

Specialist Family Violence Courts are the centrepiece of these reforms. They provide a trauma-informed response for people affected by family violence and give them more choice over their court experience. A team of specially trained magistrates, operational staff and family violence practitioners ensure that community members can access tailored and effective family violence services at court and beyond.

Specialist magistrates have the power to order respondents to attend approved counselling through the Court Mandated Counselling Order Program. This helps promote the safety of people affected by family violence by holding respondents accountable for their use of violence and supporting positive behaviour change.

Key activity in 2022

- An additional seven Magistrates’ Courts were established, bringing the total number of Specialist Family Violence Courts in operation to 12. These courts are now operating at Ballarat, Broadmeadows, Dandenong, Frankston, Geelong, Heidelberg, Latrobe Valley, Melbourne, Moorabbin, Ringwood, Shepparton and Sunshine. Two further specialist courts will be established in Bendigo in 2023 and Wyndham in 2025.

- The Remote Hearing Support Service was made available at 11 Victorian Magistrates’ Courts in 2022. This service provides specialist support to affected family members to appear remotely in their family violence proceeding from a safe and confidential location.

- The Court Mandated Counselling Order Program was rolled out to all 12 Specialist Family Violence Courts. This includes providing specialist training to judiciary and court staff. The program helps keep respondents to family violence intervention orders accountable and supports them to change their behaviour.

- We evaluated the implementation and effectiveness of the Koori Family Violence Intervention Order Breaches pilot in Mildura to inform the further development of this pilot. The pilot allowed for breaches of FVIOs to be heard in the Mildura Koori Court, rather than the mainstream Magistrates’ Court. The pilot provides victim survivors and people who use violence with a more culturally appropriate response to reduce the impacts of family violence. It also improves court users’ perceptions of the courts and reduces recidivism.

- The Integrated Counselling and Case Management Program was trialled and evaluated at the Ballarat Specialist Family Violence Court. This program provides integrated case management to address the complex interplay between family violence, alcohol and other drugs, and mental health issues.

- All Victorian Specialist Family Violence Courts have continued to implement the MARAM framework and embed it into practice. The MARAM framework supports a system-wide approach to assessing and managing the risk of family violence.

- Family violence training for interpreters was delivered over four courses to 63 participants. Feedback from this training confirmed the course had increased skills and confidence of all participants.

Dhelk Dja: Safe our way

Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families

Family violence is not a part of Aboriginal culture. Colonisation, dispossession, child removal and other discriminatory governmental policies have resulted in significant intergenerational trauma, structural disadvantage and racism. These have had long-lasting and far-reaching consequences, including a disproportionate level of family violence against Aboriginal people.

Victoria has committed to an Aboriginal-led agreement Dhelk Dja: Safe our way – strong culture, strong peoples, strong families (the Dhelk Dja Agreement) to address family violence in Aboriginal communities. The agreement is grounded in the self-determination principles within Korin Korin Balit-Djak, Victoria’s Aboriginal health, wellbeing and safety strategic plan 2017–2027.

Key activity in 2022

- We funded 33 Aboriginal-led initiatives and services under Dhelk Dja Family Violence Fund. This Fund supports eligible Aboriginal organisations and community groups to enable a range of Aboriginal-led tailored responses for victim survivors and people who use violence to reduce the disproportionate prevalence and impact on Aboriginal people and communities.

- The Aboriginal Family Violence Prevention Mapping Initiative was published in July 2022 mapped government-funded Aboriginal family violence prevention initiatives from 2016 to 2021. It found more than $18.7 million has been invested in 251 initiatives since 2016, with more than 88 per cent of this funding provided to Aboriginal community-controlled organisations (ACCOs) and community groups.

- We made significant progress towards establishing two Aboriginal Access Points, which commenced operation in 2023.1 The design of Aboriginal Access Points and the service pathways they offer has been community-led and self-determined by Aboriginal peoples and will be delivered by ACCOs.

- The Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum endorsed the Second Dhelk Dja three-year action plan. Regional action plans will be developed to support the implementation of the recently endorsed Three-year action plan and will be reviewed annually.

- We expanded the Police and Aboriginal Community Protocols Against Family Violence. This will enable statewide coverage. The protocols define a model for collaboration between police and local Aboriginal communities to address family violence. They operate in 10 Victorian areas with seven additional areas expected to commence in late 2023.

Footnotes

1 Locations include Bayside Peninsula led by the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA) and Barwon, led by Wathaurong Aboriginal Organisation.

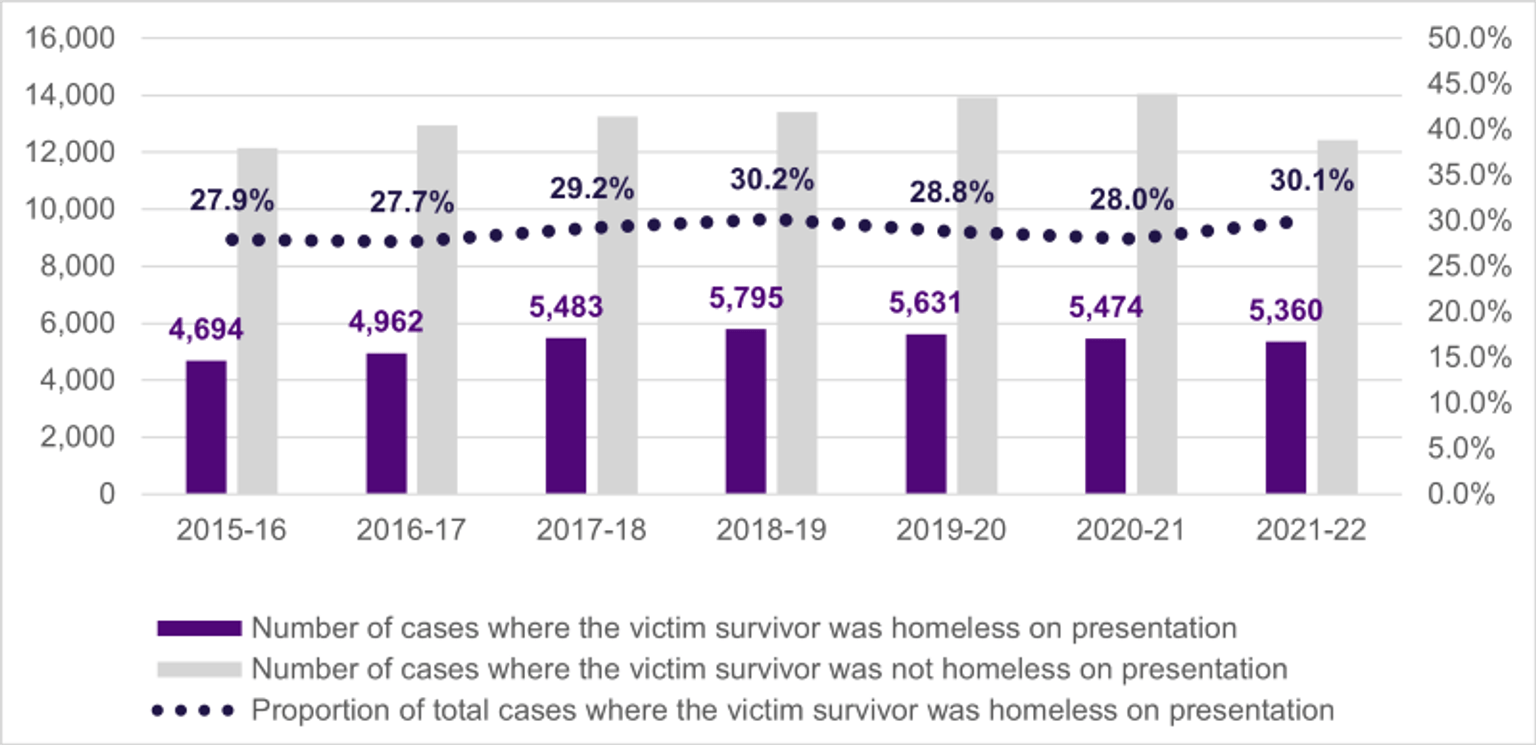

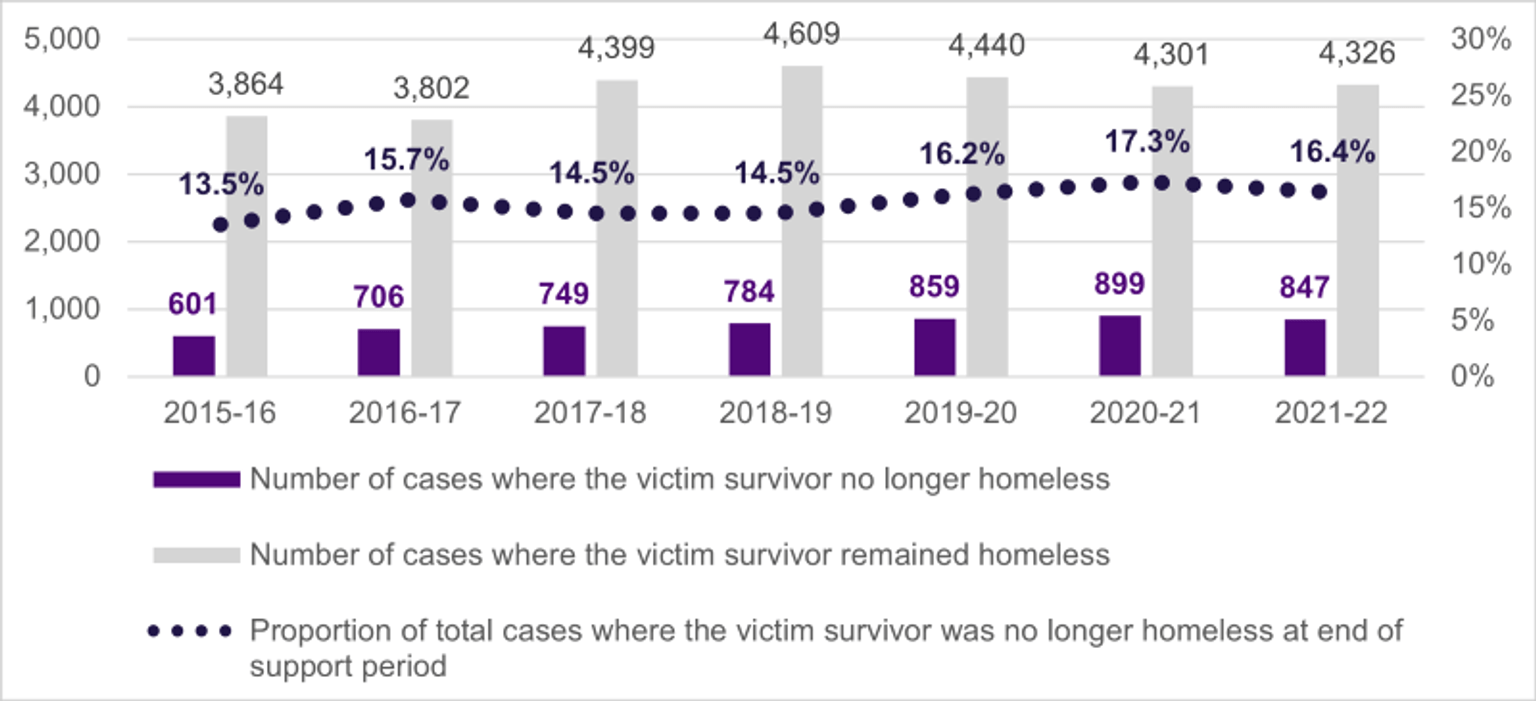

Housing

Improving access to safe and stable housing options

Safe and appropriate accommodation and housing are critical to the safety and long-term recovery of victim survivors.

While many victim survivors want support to stay in their own homes and communities, those who cannot stay at home need immediate short-term refuge followed by timely access to a stable home in a suitable location. This longer-term housing helps provide them with security and stability in their employment and education. However, family violence continues to be a leading cause of homelessness, especially for women and children.

Victoria is delivering on the $5.3 billion Big Housing Build, to increase social and affordable housing. On completion, it will deliver more than 4,200 new social housing dwellings across metropolitan Melbourne and regional Victoria. This includes the delivery of up to 1,000 dwellings for victim survivors of family violence.

Key activity in 2022

- We opened four new core and cluster refuges. These provide victim survivors with immediate access to safe independent living (known as clusters), while also offering 24/7 comprehensive support services on site (known as the core). The new refuges cater to people who have historically experienced barriers to access. This includes victim survivors with adolescent sons, victim survivors from diverse cultural and faith backgrounds, larger families, LGBTIQ+ victim survivors and those with substance dependency.

- Aboriginal-specific core and cluster refuges provide a space for Aboriginal women and children experiencing family violence to receive culturally appropriate support. One Aboriginal-specific refuge is operational, with the final two in the design phase.

- In 2021–22, we funded inTouch Multicultural Centre Against Family Violence (inTouch) to work with all refuges across Victoria to enhance service responses for victim survivors on temporary visas in refuge. This included training and capacity building for refuge staff in culturally responsive practice and working with temporary visa holders.

- The Personal Safety Initiative continued to provide safety and security planning for victim survivors including the installation of home security and/or property modifications to enable victim survivors to remain safely in their own homes, return home, or safely relocate to a new home. In 2021–22, the initiative supported 1,403 safety and security home audits, which made security and technology recommendations for victim survivors.

Legal assistance

Improving legal assistance access, representation and integration across the family violence system

We are working to improve early access to legal assistance and representation for people affected by family violence, as well as those who use violence.

One of the ways we are doing this is by integrating legal services across statewide family violence services, such as The Orange Door network.

This supports victim survivors to understand their legal options and make informed decisions about their family and safety needs. It also helps perpetrators understand police and court processes and meet any obligations associated with court outcomes.

Key activity in 2022

- The Pre-Court Engagement and Resolution Program was expanded to seven Magistrates’ Court locations following a successful pilot in Frankston. This program proactively engages people prior to their court hearing so that they are better prepared and able to understand and participate in the court process. The program is now operating in Broadmeadows, Dandenong, Latrobe Valley, Melbourne, Ringwood, Sunshine and Werribee.

- Through the Specialist Family Violence Legal Practice Model, resources were developed in consultation with people with lived experience and justice sector partners, to improve referrals to family violence legal and non-legal services before court.

- Djirra enhanced its Aboriginal Family Violence Legal Service. across metropolitan Melbourne. It also opened four new regional offices in Morwell, Echuca, Bendigo and Ballarat, bringing the total number of regional offices to seven. This service supports Aboriginal people who are experiencing or have experienced family violence. It also assists people experiencing family violence who are parents of Aboriginal children.

- Pre-separation legal information is now available on the Victorian Legal Aid website, providing free, easily accessible information to support victim survivors to understand their rights before leaving a relationship. Victorian Legal Aid also launched the Screening, Triage and Referral Tool to identify an individuals’ legal needs and direct to relevant legal information and referrals.

- Women’s Legal Service Victoria continued to deliver the Safer Families program to Community Legal Centres. This professional development program supports community legal centre lawyers to provide high-quality, effective advice and representation to clients experiencing family violence.

MARAM and information sharing

A shared approach to risk assessment and information sharing

The Family Violence MARAM framework, the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme, the Child Information Sharing Scheme and the Central Information Point support a consistent approach to assessing and managing the risk of family violence.

They also increase collaboration between services through information sharing. They support workforces to understand their responsibilities in identifying and responding to family violence. They help us respond to family violence in more accessible and equitable ways.

Key activity in 2022

- In 2021–22, 43,191 professionals across family violence, health, education, justice and other social service settings received MARAM training. This brings the total to more than 107,456 professionals from over 6,000 government and non-government organisations who have now undertaken training since commencement of the reforms in 2018.

- As part of the expanded MARAM training, frontline universal services workforces, such as health and education workers, received victim survivor-focused training to assist them to respond appropriately and effectively, including through collaboration with other services.

- Family violence training and resources aligned with the MARAM framework were developed for public maternity services. In 2022, public maternity staff completed 1,452 units of training. Key record-keeping systems were updated to include screening questions which support maternity service providers to screen and identify patients for family violence and refer them to appropriate services in accordance with the MARAM framework.

- We commenced development of additional MARAM guidance and tools for working directly with children and young people to identify, assess and manage family violence risk and wellbeing. This work is part of the continuous improvement model underpinning the MARAM framework. The standalone practice guides and tools are anticipated for release in 2024 and will support all workforces prescribed under the MARAM framework to undertake:

- direct risk and wellbeing assessment and management for children and young people as victim survivors in their own right

- risk and wellbeing assessment for young people using family violence in the home and in dating relationships

- We published and commenced implementation of the comprehensive Adults using violence MARAM practice guides to support specialist workforces responding to and working with perpetrators to identity and respond to coercive control and misidentification and to manage risks of system abuse. As part of this work, we launched the MARAM Predominant Aggressor Identification tool and practice guidance to support professionals across the family violence system, including police, to accurately identify perpetrators of family violence who are claiming to be victims.

- For further information on the implementation of MARAM in 2021–22, please refer to the MARAM framework annual report 2021–22.

Perpetrators and people who use violence

Developing a system-wide approach to keeping perpetrators accountable, connected and responsible for stopping their violence

Every time a person who uses violence interacts with the family violence service system, there is an opportunity to influence behaviour change. This change is more likely to happen when the government, the broader service system, community and society are working together to prevent violence or intervene early.

This is why we are developing a system-wide approach to keep people who use violence visible and accountable to take responsibility for their violence and change their behaviour.

Key activity in 2022

- We contributed to the draft National principles to address coercive control, with the consultation draft released in September 2022. These principles will help enable a shared understanding of coercive control across Australia and will help to inform more consistent responses. The principles are expected to be finalised in 2023.

- We increased access to men’s behaviour change programs, with over 641 placements in these programs and 203 individual case management placements in Community Correctional Services in 2021–22.

- In 2022, the Place for Change Program (formerly the Medium-term Perpetrator Accommodation Service) provided approximately 50 adults using family violence with up to six months of stable accommodation. Access to accommodation is dependent upon recipients’ behavioural and attitudinal change to address their use of violence.

- We expanded the Tuning into Respectful Relationships program bringing the total number of prisons invited into the program to 11. The short program introduces remand and short sentence prisoners to the concept of healthy relationships including building awareness of the benefits of respectful attitudes and behaviours and understanding the connection between disrespect and acts of violence. In 2021–22, Anglicare delivered this program to 206 participants including 148 men, 59 women, two transgender people and one gender-diverse person.

- We recognise many perpetrators of family violence are also clients of other social service programs. From June 2022, the Better, Connected Care reform (formerly Common Clients) operates statewide and began testing new integrated, person-centred service models through the Putting Families First pilot.

- We designed the intensive interventions for high-risk perpetrators pilot service model (the serious-risk pilot), to increase the visibility of serious-risk perpetrators across the system and the coordination and management of responses. The pilot will provide a dedicated, coordinated response to serious-risk perpetrators and victim survivors impacted by their violence. Across three sites, the pilot program will deliver intensive interventions and individual behaviour change work through specialist family violence services and multi-agency collaboration to help prevent future harm to victim survivors.

Primary prevention

Changing community attitudes and behaviours to help stop family violence and all forms of violence against women before it starts

Primary prevention aims to address the underlying drivers of family violence and all forms of violence against women to prevent violence from occurring in the first place. These drivers include gender-biased systems, structures, norms, attitudes, practices and power inequality.

Primary prevention is a long-term strategic approach that seeks to engage people of all ages in the places where they live, work, learn and play. It aims to drive social and cultural change towards a society where Victorians can live free from violence.

The Free from violence: second action plan 2022–2025 sets out our approach to primary prevention. Under this plan, we are working to scale up the most effective primary prevention approaches and increase the capability and capacity of the primary prevention workforce.

Key activity in 2022

- Respect Victoria’s three-yearly report, Progress on preventing family violence and violence against women in Victoria was tabled in Parliament in September 2022. The inaugural report spans 2018 to 2021, articulating the progress Victoria has made and outlining opportunities for future action.

- The Preventing Violence Through Sport Grants Program funded 12 partnerships to deliver prevention training in community sports settings. The partnerships comprise a diverse range of community sports clubs and leagues, local governments and women’s health services, reaching young people and communities across metropolitan, regional and rural Victoria.

- We supported 33 organisations to deliver primary prevention, awareness raising and early intervention projects with over 27 multicultural communities and five faith groups through the Supporting Multicultural and Faith Communities to Prevent Family Violence Program.

- Rainbow Health Australia developed and published the Pride in prevention partnership guide: a guide to primary prevention of family violence experienced by LGBTIQ+ communities. This guide aims to build the capacity of LGBTIQ+ organisations and practitioners and the broader prevention sector.

- Respect Victoria delivered behaviour change campaigns including the statewide Respect Women: ‘Call It Out' (Respect Is) campaign in October 2022. The campaign featured diverse stories of what respect means in the context of the drivers of violence against women.

- In partnership with Jesuit Social Services, we designed an early intervention project targeting at-risk boys and young men at critical points in their development to equip them with the skills and confidence to challenge harmful norms and attitudes that lead to violence against women.

- Up to 48,200 families benefited from the Baby Makes 3 program,1 which promotes equality in parenting by supporting new parents to build mutual respect for each other, and challenges gendered expectations of becoming a parent. Fifty-three childbirth and parenting educators completed training to deliver the program.

- Balit Booboop Narrkwarren, which means ‘strong baby and family’ in Woiwurrung language, is a culturally adapted model of the Baby Makes 3 program to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families. In 2022, an additional 11 people were trained as Balit Booboop Narrkwarren Champions to deliver the program for Aboriginal families.

Footnotes

1 HealthAbility 2022, ‘Baby Makes 3 wins VicHealth’s Outstanding Health Promotion Award 2022’, https://healthability.org.au/services/baby-makes-3/

Research and evaluation

Coordinating research and evaluation across the family violence reform

A strong evidence base is key to delivering long-term, sustainable reform of our family violence system. It tells us what is working, what needs to be adjusted and where to focus our efforts for the greatest effect.

We are focusing on research activities that fill gaps in knowledge across primary prevention, early intervention and response, and working to improve the quality, availability and use of data to build our understanding and drive improvement.

Key activity in 2022

- Victoria’s Family violence research agenda 2021–2024 was released in February 2022. It articulates the Victorian Government’s research priorities to strengthen evidence and support strategic decision-making in relation to family violence and sexual assault.

- To support the Research agenda, we funded 13 research projects across seven subject areas under the Family Violence Research Grants Program. This research is not only building evidence but also translating it into practice to support better outcomes and long-lasting change for both victim survivors and those who use violence.

- Respect Victoria progressed a number of primary prevention-focused research projects, including:

- the No more excuses report, which explores the extent and nature of violence against women with disability in Australia, and what works to prevent this violence before it starts

- the Aboriginal Family Violence Primary Prevention Research Project, which is being conducted by Urbis Consulting in partnership with Yorta Yorta researcher and community development expert Karen Milward

- the Migrant and Refugee Women and Girls Research Project, conducted by Monash University, explores the ways that that primary prevention and coercive control are understood by migrant and refugee Victorians, with a particular focus on women and their experiences

- the Evidence Synthesis Review Project, which sought to strengthen understanding of the similarities and differences in what drives different forms of family violence and violence against women.

- The Harmony Study, conducted by Latrobe University in partnership with the inTouch Multicultural Centre Against Family Violence, worked with primary care clinicians to increase their ability to identify and intervene early in situations of family violence among migrant and refugee communities.

- The Dhelk Dja monitoring, evaluation and accountability plan was prepared by the Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum to accompany Dhelk Dja: Safe our way – strong cultures, strong peoples, strong families.

- The Family Violence Data Portal is updated every quarter. Since its creation, there have been several modifications to include new data. For example, sexual violence data was added to the portal for the first time on 1 December 2021 and is regularly updated.

- Evaluations of family violence initiatives were undertaken in 2022. This included the evaluation of the Risk Assessment and Management Panels (RAMPs) which provided a set of themed recommendations and next steps to inform future directions for RAMPs.

The Orange Door network

Delivering an accessible and visible service for people experiencing family violence and children and families in need of support

The Orange Door network is the first of its kind in Australia.

It provides a single visible and accessible entry point for Victorians to access family violence, child and family services and Aboriginal services. This single-entry point means individuals and families are able to engage with one service to meet their current needs and navigate broader system responses without having to re-tell their story.

Through the Victorian Government’s partnerships with community service organisations, The Orange Door network provides tailored support for:

- adults, children and young people who are experiencing family violence

- families who need support with the care and wellbeing of children and young people

- perpetrators and people who use family violence.

Key activity in 2022

- Through the opening of Orange Doors in Brimbank Melton, Wimmera, Outer Eastern Melbourne, Hume Merri-bek and Western Melbourne, the statewide rollout of The Orange Door network across Victoria was completed.

- In 2022, more than 164,000 people, including 69,000 children accessed both immediate and longer-term support through The Orange Door network, bringing the total number of people supported by The Orange Door to 303,000, including 121,000 children, by the end of 2022.

- We commenced implementation of The Orange Door Aboriginal inclusion action plan.

- As part of the implementation of the Lived experience strategy, we commenced the second evaluation of The Orange Door network. The evaluation considered client experiences of The Orange Door and was designed and delivered in collaboration with peer evaluators who have lived experience of family violence or the child and family services system.

- In October 2022, The Orange Door in the Bayside Peninsula area commenced a pilot to connect clients of The Orange Door with legal services, which allows clients access to a dedicated lawyer with their Orange Door Practitioner present in a supportive and trauma-informed environment.

- We implemented the Strengthening Cultural Safety Training Program in all The Orange Door locations where there is a partnership in place with a local Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisation. Cultural Safety Project Leaders have been employed to facilitate cultural safety self-assessments and provide foundational training to The Orange Door staff.

- We progressed The Orange Door partnership performance framework including development of initial measures and data collection, with trial reporting to commence in 2022–23.

- The Orange Door induction training has been refreshed.

- A suite of operational guidance has been developed to support integrated practice in operational areas of The Orange Door. This includes guidance on workflows that support the interdisciplinary teams across all Orange Door networks.

Workforce development

Strengthening the specialist family violence and primary prevention workforces

Strengthening the capability of the people who work to prevent and respond to family violence is critical to reform success.

We are also building the family violence capabilities of workforces that intersect with family violence including community services, health, police, courts, schools and early years services.

The focus for the Rolling action plan is to continue to strengthen our specialist prevention and response workforces by:

- recruiting and retaining people with skills from diverse backgrounds

- working to create clear career pathways that develop expertise and knowledge

- providing training and skills development

- creating a workplace where people feel valued and supported.

Key activity in 2022

- In 2022, over 1,700 individuals completed the course in Identifying and Responding to Family Violence Risk. This free TAFE course delivers foundational family violence knowledge and skills to undertake MARAM screening and identification. It is targeted to universal services workers.

- We delivered the Fast Track Program, supporting 127 mid-career and senior practitioners to develop skills and capabilities in family violence prevention and response. Program participants directly attribute workplace achievements to the confidence and capabilities gained through the Program.

- In July 2021, the Mandatory Minimum Qualifications Policy for specialist family violence response practitioners commenced with a five-year transition period. Under the policy, new specialist family violence practitioners must hold a minimum of a social work degree or equivalent qualification or be working towards this. Almost $2 million in adjustment funding was distributed across 78 organisations.

- In partnership with 22 Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations, we delivered a scholarship program for 33 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employees to support them meeting the Mandatory Minimum Qualifications Policy. The scholarship program builds on the existing investment in upskilling and expanding the Aboriginal family violence workforce.

- The Family Violence and Sexual Assault Traineeships Program piloted, with 312 trainee places funded across 31 family violence, sexual assault, primary prevention and community services organisations to support workers undertake further education and training.

- In 2022, 52 graduates and 57 trainees commenced in funded roles designed to build capacity within the family violence, sexual assault and prevention sector.

- We published the Family violence workforce health, safety and wellbeing guide. The guide provides evidence-based tools and guidance that recognise the health, safety and wellbeing impacts experienced by the family violence workforce. It supports promoting and protecting the health, safety and wellbeing of employees in the workplace and enables practitioners and organisations to become advocates for workplace health, safety and wellbeing.

Family Violence Outcomes Framework

Translating our vision of a Victoria free from family violence into a quantifiable set of outcomes, indicators and measures

The Family Violence Outcomes Framework translates our vision for a Victoria free from violence into a quantifiable set of outcomes, indicators, and measures.

The framework comprises four domains that reflect the long-term changes we want to achieve through our family violence reforms. These are:

- Prevention: Family violence and gender inequality are not tolerated

- Victim Survivors: Victim survivors, vulnerable children, and families are safe and supported to recover and thrive

- Perpetrators: Perpetrators are held accountable, connected, and take responsibility for stopping their violence

- System: Preventing and responding to family violence is systemic and enduring

Each domain contains a set of outcomes, indicators and measures. A short definition for each of these terms is provided in the table below.

Definitions of outcomes, indicators and measures

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Outcomes | Articulate what success looks like, and are clear, unambiguous, high-level statements about the things that matter to prevent family violence in Victoria |

| Outcome indicators | Specify what needs to change to achieve each outcome and set the direction of change, for example, are we looking for an increase or decrease? |

| Outcome measures | Provide the more granular and specific details about what will change and how we will know if we are making progress. They enable us to determine the size, amount or degree of change achieved |

The Family Violence Outcomes Framework measurement and monitoring implementation strategy sets out our staged approach to measuring and monitoring the outcomes of family violence reform in Victoria.

This approach is founded on our understanding that it will take time to address data gaps, strengthen the validity and reliability of data sets, and build capability and capacity across the family violence system to collect, analyse, and report outcomes data.

Strengthening how we measure family violence outcomes

The outcomes framework provides a clear focus on the long-term outcomes we are working towards. However, we still have considerable work to do to strengthen the indicators and measures, increase the quality of data we have access to, and use that data in more sophisticated ways.

This will help us better understand the impact of our work and more meaningfully report on the outcomes we are achieving.

There are two key challenges we working to address:

1. Tracking our progress against long-term outcomes

Currently, the outcomes, indicators, and measures relate to long-term goals and use population-level data. While these are important elements of a statewide outcomes framework, they are not sensitive to change in the short-term. This makes it difficult to track our progress as we work towards our long-term goals. When data is at population level, it is also more difficult to measure the impact of reforms on particular communities to inform decision-making about where additional effort or investment may be required.

2. Strengthening data quality and availability

Measuring outcomes and monitoring progress requires different types of data across each of the four domains. For example, the Prevention domain uses program and project-level data gathered through community partners that are delivering primary prevention initiatives. The data relates to the specific projects they deliver and there is little consistency and few systems in place to track the collective outcomes of these projects.

The Victim Survivors, Perpetrators and System domains rely heavily on service delivery data, which comes from four key datasets: police incidents, intake (The Orange Door, Safe Steps and Men’s Referral Services), case management and refuges, and program data from both therapeutic programs and Men’s Behaviour Change Programs.

The systems supporting these datasets were developed at different times and sit on different platforms that do not to talk to one another. This makes it difficult to track client journeys through the family violence system and therefore measure outcomes.

These challenges are not unique to Victoria. Strengthening data collection systems is also a key priority under the National plan to end violence against women and children (2022–2032).1

To address these challenges, we will:

- develop meaningful short- and medium-term indicators and measures

- identify data sources for all measures by mapping reform initiatives, exploring opportunities to link datasets, and creating new data sets to address gaps

- enter into data-sharing agreements with data custodians to develop linked datasets and mandate how data is collected and analysed

- develop a data improvement strategy to strengthen data quality, reliability, and availability

- develop data collection tools and systems to report and analyse data, and integrate them into programs, services, and evaluations

- disseminate guidance materials that are clear, specific, and practical to implement.

Domain overview and related data

Footnotes

1 Commonwealth Government 2023, National plan to end violence against women and children 2022–2032, p. 27. https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/11_2022/national_p…

Domain 1: Prevention

Family violence and gender inequality are not tolerated

Most violence, including family violence, is committed by men.1 This violence is grounded in gender inequality. It is driven by men’s control of decision-making, limits to women’s independence, rigid gender stereotypes, cultures of masculinity that emphasise aggression, dominance and control, and the condoning of violence against women.2

Primary prevention focuses on stopping family violence and violence against women before it starts. This requires coordinated action across multiple settings that challenge the attitudes, social norms, and behaviours that perpetuate gender inequality and condone violence towards women.

Victoria’s approach to primary prevention is set out in Free from violence: Victoria’s strategy to prevent family violence. It was launched in 2017. The strategy guides our engagement with Victorians of all ages and from all communities to prevent family violence in all the places where they live, work, learn and socialise.

We do this work in partnership with local councils, women’s health services, maternal and child health services, multicultural, youth and community organisations, sporting clubs, educational institutions, settlement services and workplaces. Respect Victoria plays a critical role as Victoria’s dedicated organisation for the prevention of family violence and violence against women.

Prevention outcomes we are working towards

- Family violence and gender inequality are not tolerated.

- Victorians hold attitudes and beliefs that reject gender inequality and family violence.

- Victorians actively challenge attitudes and behaviours that enable violence.

- Victorian homes, organisations and communities are safe and inclusive.

- All Victorians live and practise confident and respectful relationships.

Strengthening our data

To address the challenges with long-term, population-level outcomes, we are developing short- and medium-term indicators and measures for our prevention work. These are milestones on the pathway to driving down family violence and violence against women in Victoria. They will help us know we are on track to achieving our long-term outcomes.

Currently, we rely heavily on population-level data to understand changes in the Victorian community’s understanding of, and attitudes about, violence against women. We are working to identify additional sources of data from programs and initiatives delivered in the community.

Program-level measures are currently being piloted through evaluations of primary prevention programs to test whether they are fit-for-purpose, and ensure there is consistency in outcomes data collection, analysis and reporting. Including this additional data from evaluations will enable us to better understand both the individual and collective impact of prevention programs across Victoria.

The next steps for the ‘Prevention’ domain include confirming the feasibility of data sources, establishing data-sharing agreements with data custodians, developing data collection tools and systems for reporting data, and integrating these into programs and projects. Implementation will be supported by guidance materials.

Data in this report

The primary prevention data in this report is drawn from two population-level representative surveys:

- the National Community Attitudes Towards Violence Against Women Survey (NCAS), administered by Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS)

- the Personal Safety Survey (PSS), administered by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).

These data sources allow us to monitor attitudes over time. This includes community understanding of violence against women, attitudes towards this violence and towards gender equality, and the prevalence of violence in Victoria.

They also enable the monitoring of societal norms and practices in relation to gender equality and the drivers of violence against women, as well as the proportion of women in Victoria who experience sexism, sexual harassment and gender discrimination.

While there are four long-term outcomes in the ‘Prevention’ domain, only three have data available. The outcome, ‘Victorian homes, organisations and communities are safe and inclusive’ does not have data to report against the measure ‘Proportion of women who feel safe walking home at night’. The Australian Bureau of Statistics has not released Victorian data for this measure from the Personal Safety Survey.

Footnotes

1 Our Watch 2019, Men in focus: summary of evidence in review. https://media-cdn.ourwatch.org.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/11/06…

2 Our Watch 2018, Change the story: a shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women in Australia, 2nd ed. https://www.ourwatch.org.au/resource/change-the-story-a-shared-framewor…

1.1 Victorians hold attitudes and beliefs that reject gender inequality and family violence

Indicator: Increased awareness of what constitutes violence

Being able to identify violence is critical, as it can prompt people to seek help or report if they have, or someone they know has, experienced domestic violence, sexual assault, harassment or other forms of violence. Understanding that violence includes a range of behaviours, including non-physical forms of violence, such as emotional, financial or technology-facilitated abuse, can contribute to a shift in attitudes that condone or minimise these types of violence.

This indicator provides insights into the level of understanding of what domestic violence and violence against women looks like, and whether advocacy and awareness raising efforts are having an impact.

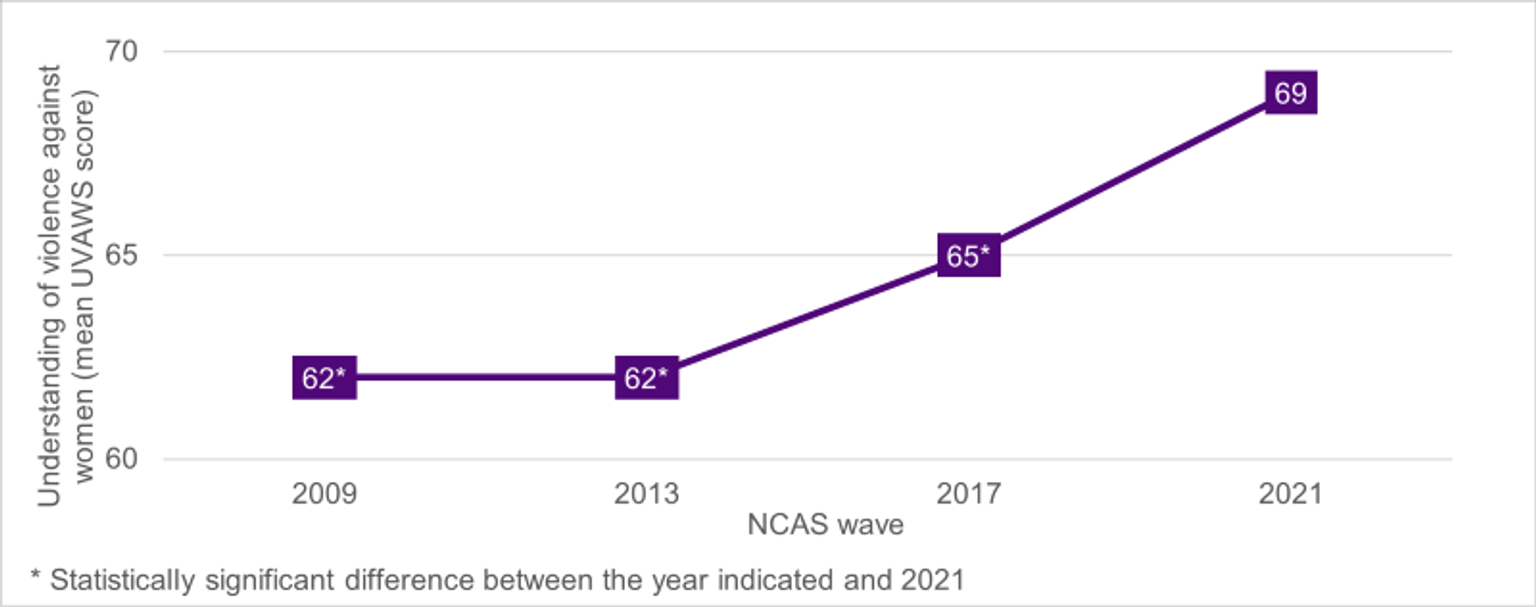

Measure: Victorian mean score on the Understanding of Violence Against Women Scale (UVAWS)

The Understanding of Violence Against Women Scale (UVAWS) examines whether people recognise the range of violent, abusive, and controlling behaviours as domestic violence and violence against women, and that men are the main perpetrators of this violence.

Figure 1 shows that Victoria had a significantly higher mean UVAWS score in 2021 compared with 2009, 2013 and 2017. This finding indicates a significant increase over time in Victorians’ understanding of violence against women.

UVAWS subscale scores indicate an improvement in Victorians’ understanding of the different behaviours that constitute domestic violence and violence against women more broadly. Both the subscales scores for ‘Recognise violence against women’ (68) and ‘Recognise domestic violence’ (69) were significantly higher for Victoria in 2021 compared to all previous years.

Despite these improvements, 39 per cent of Victorians still believe domestic violence was perpetrated by men and women equally in 2021. This is despite Personal Safety Survey, police and court data clearly showing that most perpetrators are men, and most victims and victim survivors are women.

This suggests Victorians, like Australians more broadly, are generally better at recognising behaviours that constitute domestic violence than they are at understanding that domestic violence is highly gendered in that it is disproportionately perpetrated by men against women.

Indicator: Decrease in attitudes that justify, excuse, minimise, hide or shift blame for violence

This indicator relates to condoning violence against women, which is one of the four gendered drivers of family violence and violence against women identified in Change the story.

Violence against women can be condoned or excused through social attitudes and norms, practices or structures. For example:

- justifying violence against women on the basis that it is acceptable for men to use violence in certain circumstances

- excusing violence by attributing it to external factors or implying that men cannot be held fully responsible for their own behaviour

- trivialising violence based on the perception that its impacts are not serious enough to warrant action

- downplaying violence by denying it seriousness, that it occurs or denying that certain behaviours constitute violence

- shifting blame for the violence from the perpetrator to the victim.

This indicator is important to monitor, because evidence indicates that when societies, institutions, communities or individuals support or condone violence against women, the prevalence of violence is higher.1 Men who hold these beliefs are more likely to perpetrate violence against women, and both women and men who hold these beliefs are less likely to support victims and hold perpetrators to account.2

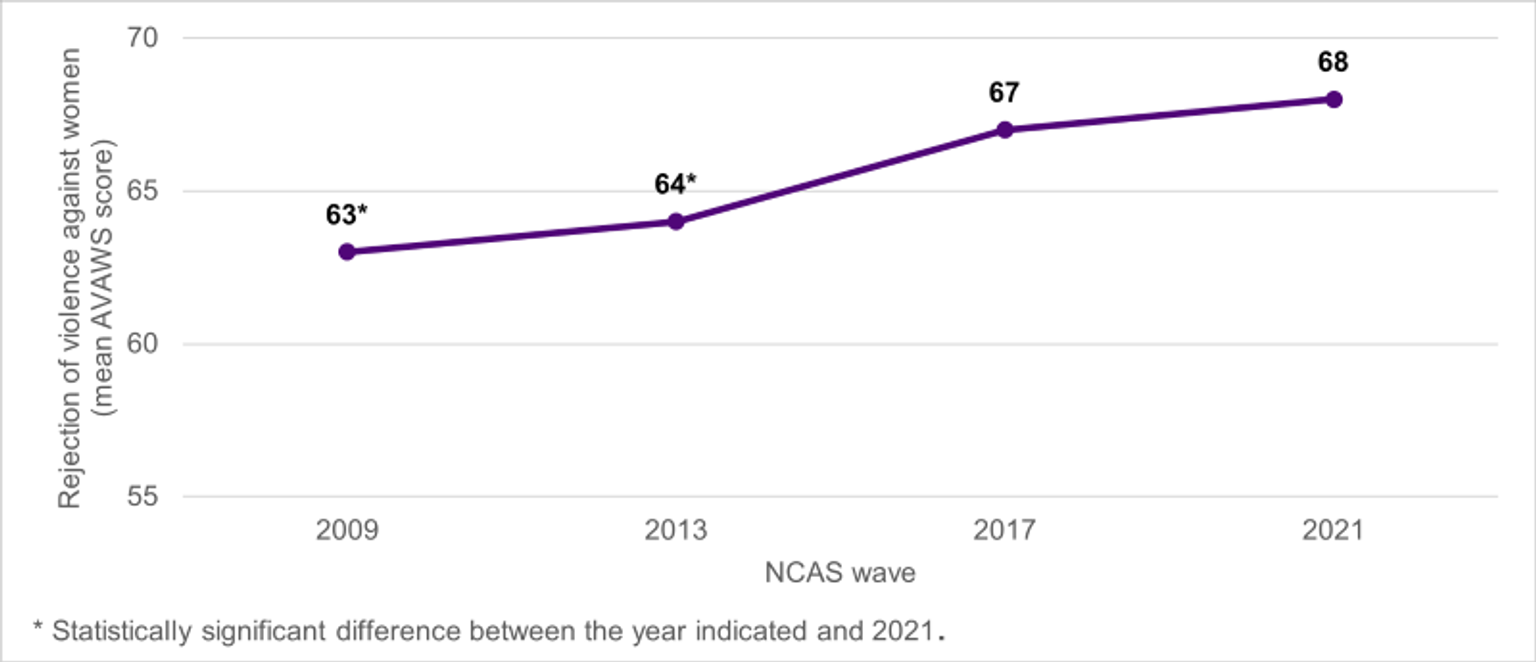

Measure: Victorian mean score on the Attitudes towards Violence Against Women Scale (AVAWS)

The Attitudes towards Violence against Women Scale3 (AVAWS) measures the rejection of problematic attitudes regarding violence against women. These include attitudes that minimise violence against women, distrust women’s reports of violence, and objectify women or disregard consent.

The mean AVAWS score for Victoria was significantly higher in 2021 than it was in 2009 and 2013. This indicates a significant increase over time in attitudes that reject violence against women (Figure 2). However, like the rest of Australia, no significant increase in AVAWS scores was observed in Victoria between 2017 and 2021. This was largely due to a plateau in attitudinal rejection of domestic violence; Victorians’ rejection of sexual violence did significantly improve between these years.

There were improvements over time on two of the AVAWS subscales for Victoria:

- the ‘Mistrust women’ subscale indicated increased rejection of attitudes that women lie about being victimised to gain some advantage (68 per cent in 2021 compared with 66 per cent 2017; this scale was not included in the 2009 and 2013 survey)

- the ‘Minimise violence’ subscale indicated increased rejection over the longer term of attitudes that downplay the seriousness of violence and shift blame to victims and survivors (from 65 per cent in 2009 to 69 per cent in 2021). However, this rejection plateaued between 2017 and 2021, with no statistically significant change between these years.

There was no significant improvement in Victoria on the ‘Objectify women’ subscale between 2017 and 2021. The ‘Objectify women’ subscale measures attitudes that objectify women and disregard consent. This does not necessarily mean that Victoria is lagging behind other jurisdictions. Instead, it indicates Victoria progressed more slowly compared to the national average on those subscales between 2017 and 2021.

These results are a reminder that changing the deeply held attitudes that allow violence to occur is not easy. It is complex, long-term work that requires dedicated focus, investment and effort across the community.

Footnotes

1 European Commission 2010, Factors at play in the perpetration of violence against women, violence against children and sexual orientation violence: A multi-level interactive model. European Commission, Brussels. https://www.humanconsultancy.com/assets/factor-model-en/index.html

2 Heise L 2011, What works to prevent partner violence: an evidence overview. Department for International Development, United Kingdom. https://www.oecd.org/derec/49872444.pdf

3 Note that the wording of this scale in the NCAS has changed since the publication of the Family Violence Outcomes Framework implementation strategy, and the measure here has been adjusted to reflect this.

1.2 Victorians actively challenge attitudes and behaviours that enable violence

Indicator: Decrease in sexist and discriminatory attitudes and behaviours

As noted in Change the story, there is a strong and consistent association between gender inequality and levels of violence against women. Indeed, there are significantly and consistently higher rates of violence against women in countries characterised by gender inequality and poor human rights protections.1

The NCAS shows that the strongest predictor of violence-supportive attitudes and a lower understanding of violence against women is the degree to which respondents hold sexist attitudes.2

Tracking this indicator is important to understand the prevalence of sexist and discriminatory attitudes in Victoria. It also tells us whether efforts to promote attitudes and behaviours that support gender equality are having an impact at the population level.

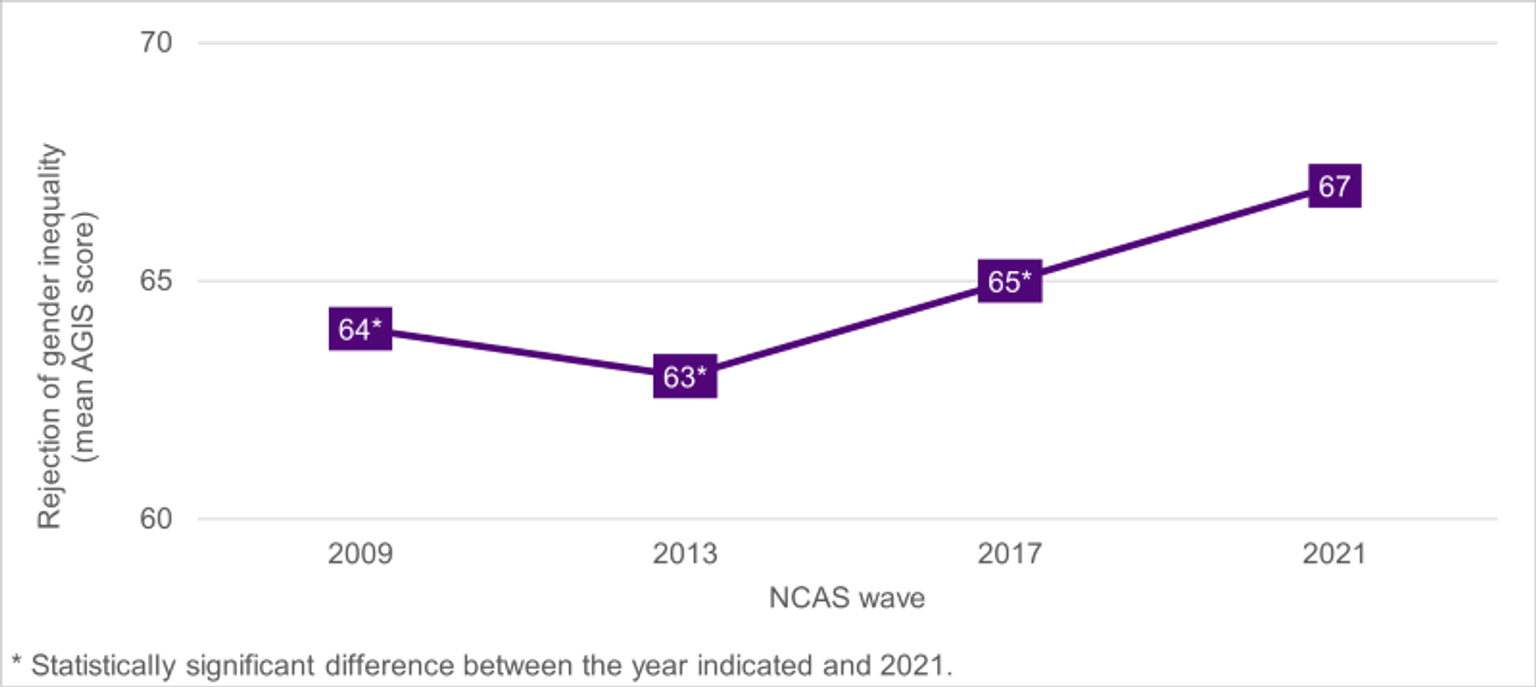

Measure: Victorian mean score on the Attitudes towards Gender Inequality Scale (AGIS) Scale3

The Attitudes towards Gender Inequality Scale (AGIS), generated through the NCAS, measures rejection of problematic attitudes regarding gender inequality. These include attitudes that reinforce gender roles, undermine women’s leadership in work and public life, limit women’s autonomy in intimate relationships, normalise sexism and deny inequality.

The Victorian mean AGIS score was significantly higher in 2021 compared with 2009, 2013 and 2017 (Figure 1).

This finding indicates a significant increase over time in Victorians’ attitudes that reject gender inequality. This is a positive sign of progress in Victoria, and it is reasonable to suggest that our efforts to advance gender equality and prevent violence against women have contributed to this progress.

The AGIS subscale findings indicate increased rejection by Victorians of attitudes that:

- limit women’s autonomy in intimate relationships (64 per cent in 2009 to 66 per cent in 2021)

- downplay sexism (64 per cent in 2017 and 66 per cent in 2021)

- reinforce traditional, rigid gender roles (66 per cent in 2017 to 67 per cent in 2021).

However, there was no significant improvement in the ‘Undermine leadership’ subscale or the ‘Deny inequality’ subscale between 2017 and 2021, indicating little or no change in attitudes that undermine women’s leadership in work, public life and attitudes that deny gender inequality experiences.

Overall, these results show us that Victoria’s long history of investing in gender equality is having an impact. This foundational work sets a strong base to support our primary prevention efforts to challenge the underlying drivers of gendered violence. It will take some time for the impact of this work to flow through in the form of community-wide changes in attitudes and behaviours.

Indicator: Decrease in prevalence of reported workplace and everyday sexism, sexual harassment, and gender discrimination

Tracking the prevalence of sexism, sexual harassment and gender discrimination in workplaces and everyday settings enables us to see whether these forms of discrimination and violence are decreasing over time. This helps us understand whether our efforts to progress gender equality and prevent violence against women are having an impact.

Tracking these forms of discrimination and violence is also important because they are connected to the drivers of violence against women more broadly, including within families and intimate relationships.

We know that sexual assault is under-reported to Victoria Police. Evidence suggests this is because of mistrust in formal state systems, such as police and the courts, and in workplace processes. Data from the Personal Safety Survey captures family violence perpetrated against victim survivors who may have chosen not to report to police.

Measure: Proportion of Victorian women aged 18 years and over who have experienced sexual harassment (in any setting) in the last 12 months

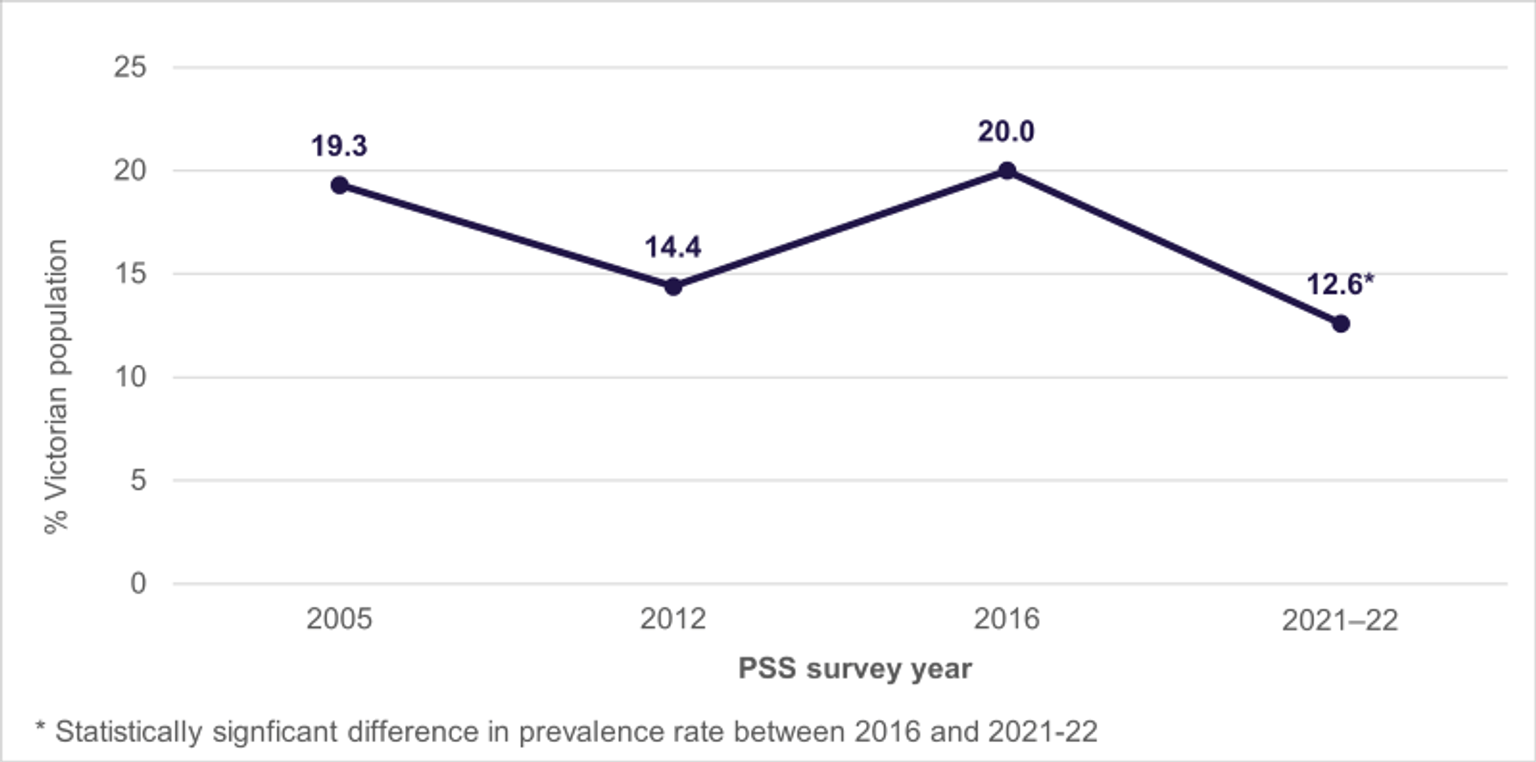

The rate of sexual harassment against women over a 12-month period has fluctuated since 2005. However, the survey indicates that the percentage of Victorian women who experienced sexual harassment within the 12-month period from 2021–22 is the lowest it has been since the PSS survey began.

Although 2021–22 PSS state and territory results by gender are not yet available, the Australia-wide results show women are almost three times as likely as men to have experienced sexual harassment in the previous 12-months.

Footnotes

1 United Nations Women 2011, In pursuit of justice: progress of the world’s women. UN Women, New York. https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2011/1/…

2 Coumarelos C, Weeks N, Bernstein S, Roberts N, Honey N, Minter K and Carlisle E 2023, Attitudes matter: The 2021 National Community Attitudes towards Violence against Women Survey (NCAS), Findings for Australia, research report 02/2023, ANROWS.

3 Note that the wording of this scale in the NCAS has changed since the publication of the Family Violence Outcomes Framework implementation strategy, and the measure here has been adjusted to reflect this.

Domain 2: Victim survivors

Victim survivors, vulnerable children and families, are safe and supported to recover and thrive

The Royal Commission highlighted how complex the family violence and sexual assault service systems were for victim survivors and families. Many people did not know what supports were available or how to access them. When people did seek help, they encountered a system that was difficult to navigate.

Under the reform, victim survivors are accessing more timely and responsive assistance, tailored to their individual circumstances. Supporting victim survivors is at the heart of the many changes across family violence services, housing, Victoria Police and the Magistrates’ Court.

The Royal Commission also found children and young people were often the ‘silent victims’ of family violence, but that this was shifting with children and young people being increasingly recognised as victim survivors in their own right. It found there was a need for dedicated support for children and young people, tailored to meet their distinct needs.

Since 2016, significant progress has been made in strengthening our response to children and young people as victim survivors in their own right and to drive change where children and young people interact with the system.

Our outcomes

Victim survivors, vulnerable children and families are safe and supported to recover and thrive

- Families are safe and strong.

- Victim survivors are safe.

- Victim survivors are heard and in control.

- Victim survivors rebuild lives and thrive.

Strengthening our data

To measure our outcomes for victim survivors, we rely heavily on service delivery data to track change and the impact of reforms over time. This data is drawn from four key datasets: police incidents, intake services across The Orange Door, Safe Steps and men’s referral services, case management and refuges, and therapeutic programs.

As previously mentioned, the current data sets captured across these systems are dependent on distinct platforms that do not connect. One of the challenges we need to address is that, currently, these datasets do not talk to one another to track client progress across different types of services. This makes it difficult to monitor victim survivors’ journeys through the family violence system and to measure outcomes across the system.

Across Australian states and territories, there is increasing commitment to strengthen family violence and sexual assault data collection systems. This is reflected as a priority under the National plan to end violence against women and children 2023–2032.

Work is also under way to develop short- and medium-term indicators and measures for victim survivors with a clearer connection to reform activities.

Data in this report

Data for the ‘Victim survivor’ domain has been sourced from the Crime Statistics Agency, the Victorian Police Law Enforcement Assistance Program and the Coroners Court of Victoria. Other data sources are Homelessness Data Collection, and the Orange Door Client Relationship Management (CRM) system.

2.1 Families are safe and strong

Indicator: Reduction in children and young people who experience family violence

Victoria’s family violence reforms recognise children as victim survivors in their own right. Any exposure they may have to family violence, is considered as part of a family violence incident.

This violence has a profound effect on children. It can affect their physical and mental wellbeing, development, and schooling, and is the leading cause of children’s homelessness in Australia.1

Measure: Number/proportion of unique affected family members who are children

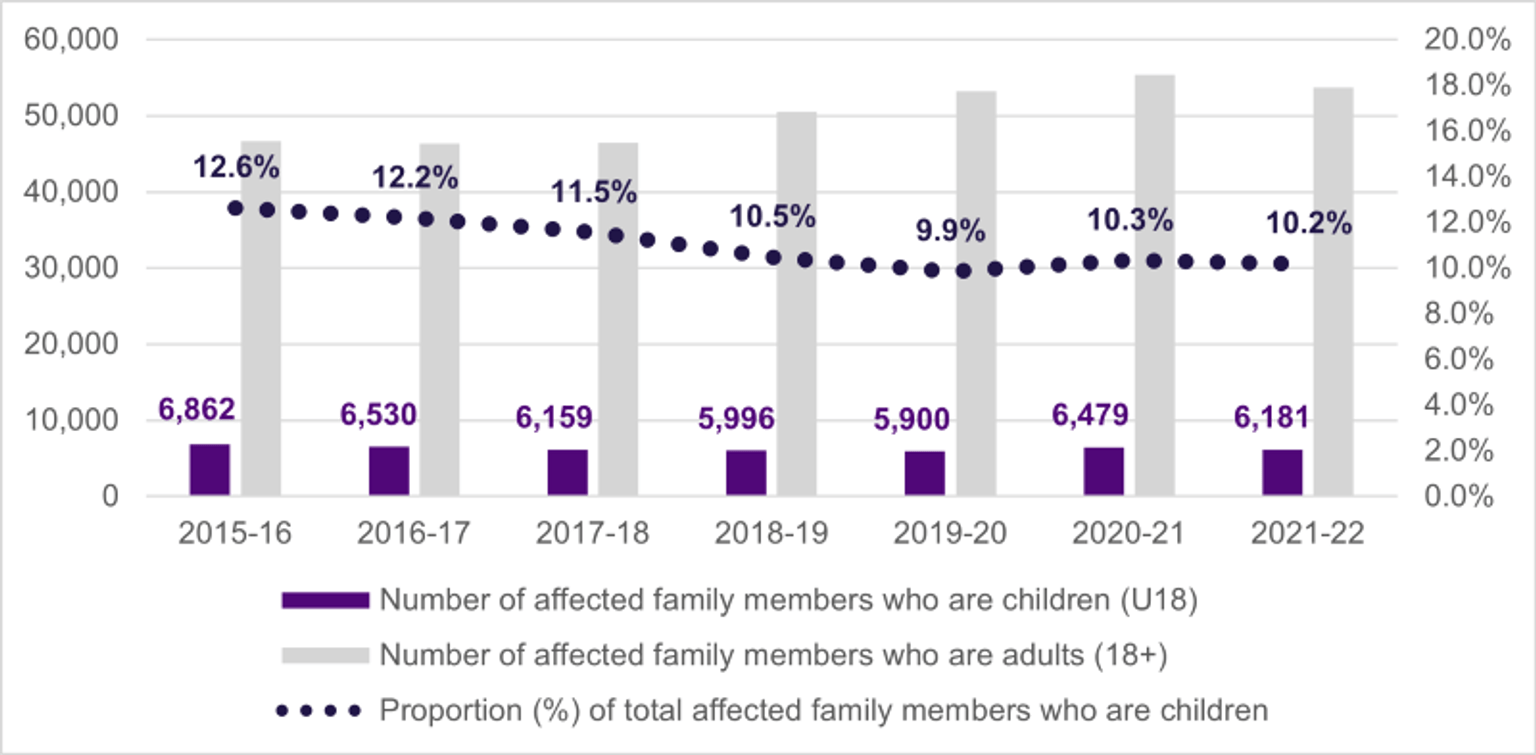

A total of 6,181 children were listed on family violence incident reports to police in 2021–22, representing just over 10 per cent of affected family members in police reports.

Generally, the percentage of children recorded as affected family members has been decreasing slightly each year since 2015.

Measure: Number/proportion of unique affected family members who are children – by Aboriginal status

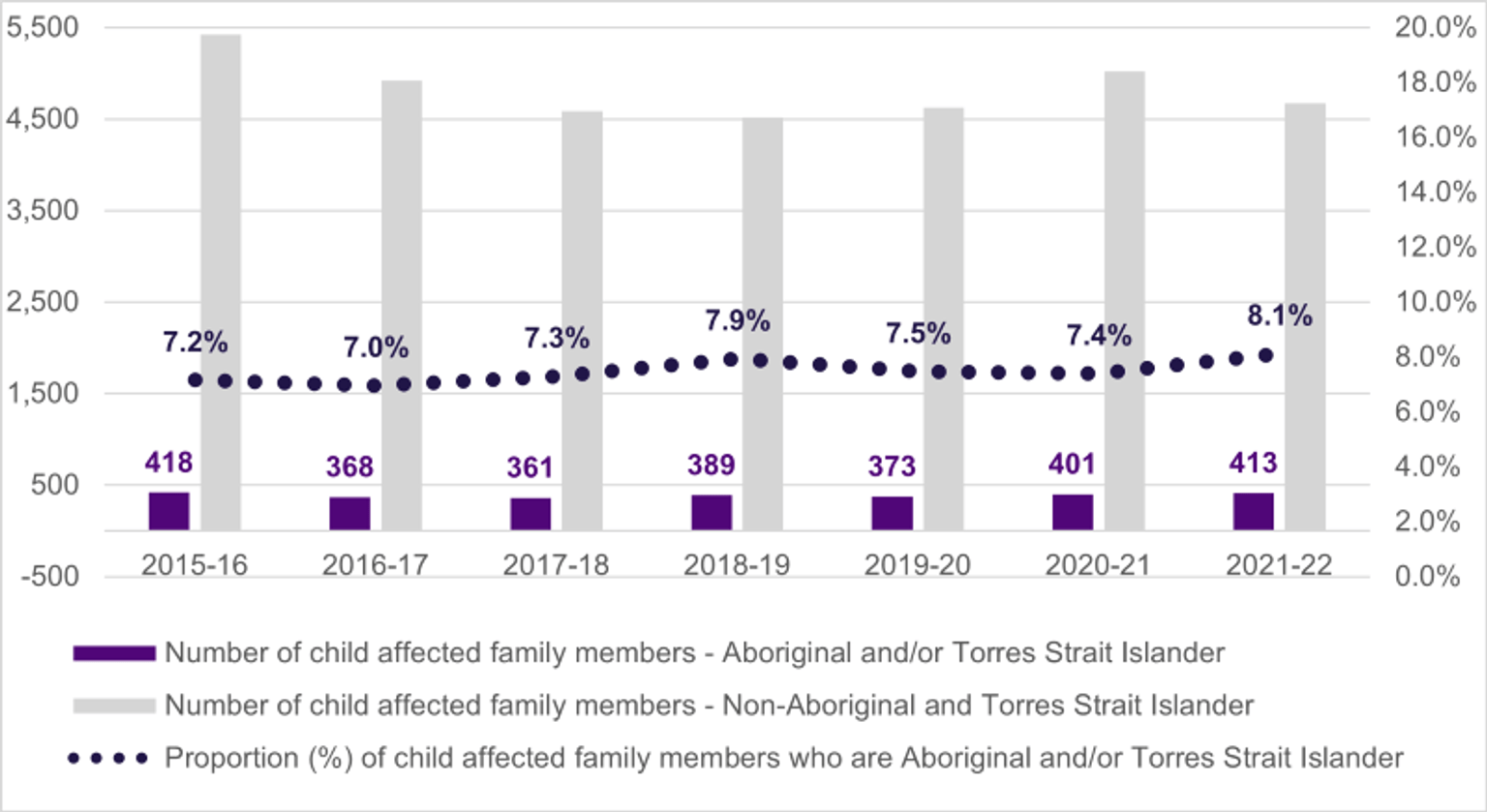

Where Aboriginal status is known, 8.1 per cent of children recorded as affected family members in 2021–22 identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander.

Although the proportion of child affected family members who are Aboriginal has remained relatively stable, 8.1 per cent is the highest proportion since 2015–16. We will monitor this closely in 2023 to determine if a trend is emerging.

Aboriginal children are overrepresented as a cohort. The 2021 Census (Australian Bureau of Statistics) indicates Aboriginal and Torres Strait children make up 1.8 per cent of the total child population in Victoria (0–17 years old).

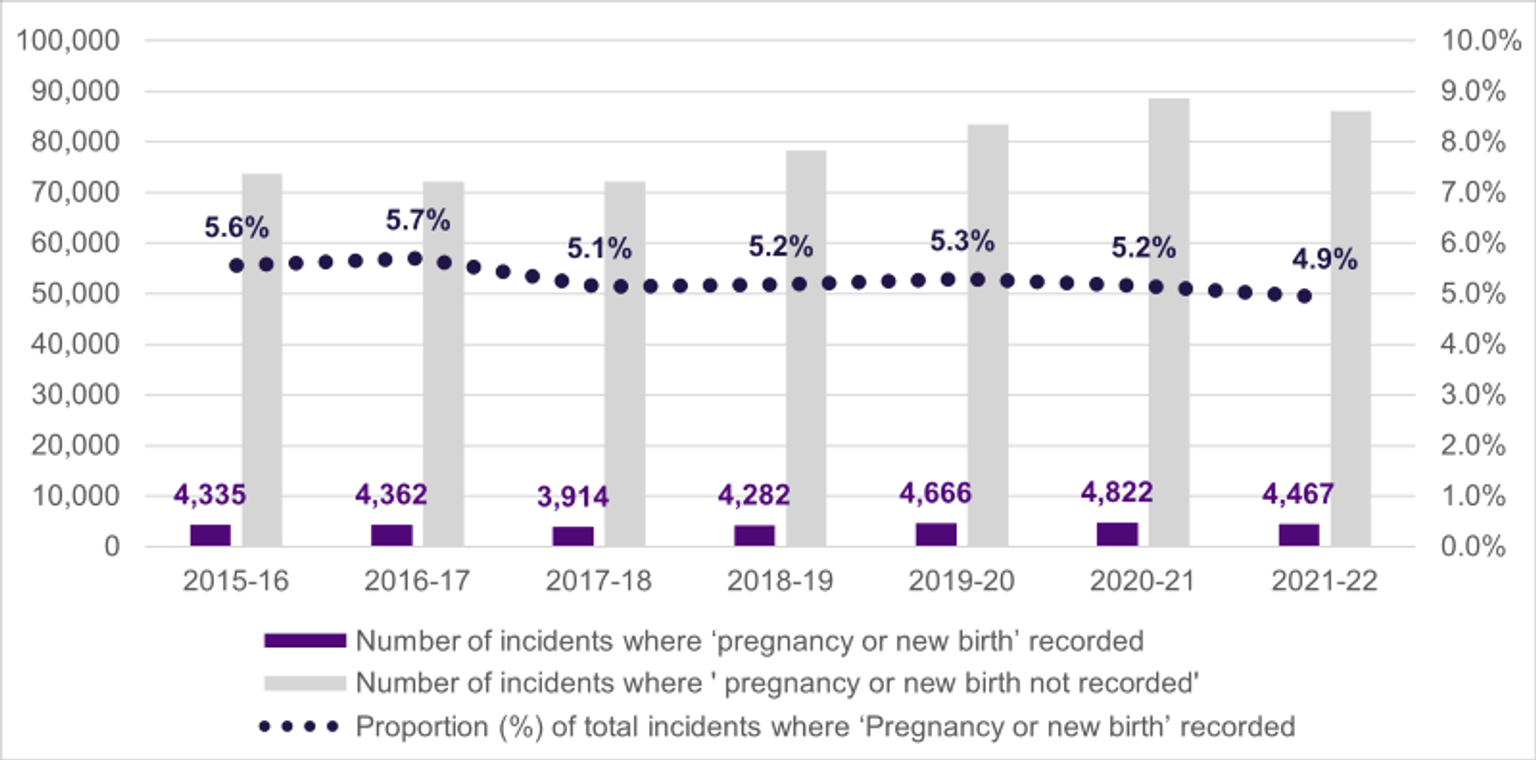

Indicator: Reduction in family violence among women who are pregnant or have a newborn

Family violence during pregnancy is a significant indicator of future harm to the woman and her children. Family violence often commences or intensifies during pregnancy. It is associated with increased rates of miscarriage, low birth weight, premature birth, foetal injury and foetal death.

Pregnancy and early parenthood are opportune times for early intervention, as women are more likely to have contact with health and other professionals.

Measure: Number/proportion of family violence incidents where ‘pregnancy or new birth’ is recorded

In 2021–22, there were 4,467 family violence incidents attended by Victoria Police where pregnancy or new birth was recorded as a risk factor. This equates to 4.9 per cent of total annual family violence incidents attended by Victoria Police.

Time series data shows the proportion of incidents where this risk factor is recorded has remained relatively stable over the past seven financial years (between 4 and 6 per cent). However, the 2021–22 level is the lowest it has been over these seven years.

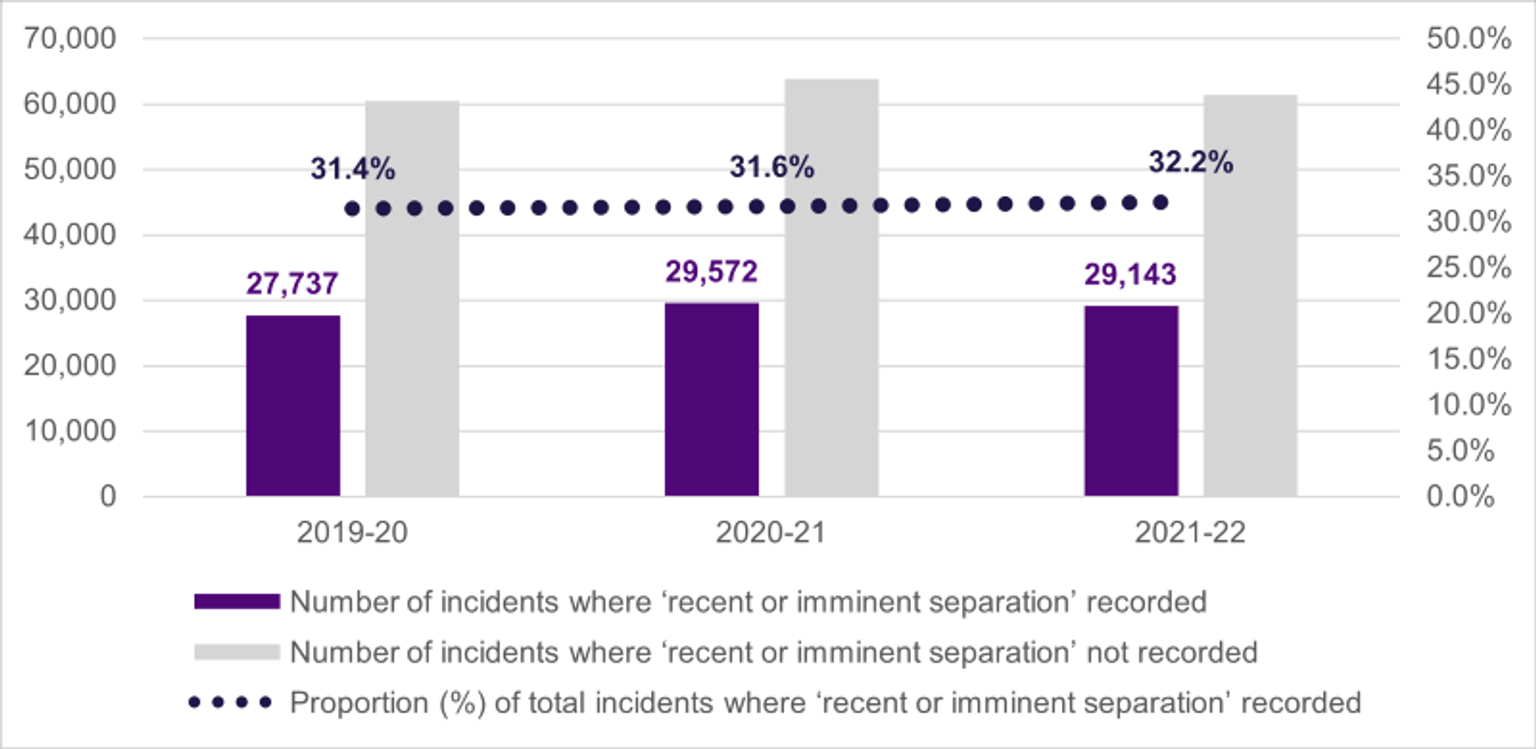

Indicator: Reduction in level of risk for victim survivors immediately post-separation

High-risk periods for people experiencing family violence include when a victim survivor starts planning to leave, immediately prior to taking action, and during the initial stages of, or immediately after, separation.

It is common for perpetrators to continue, and often escalate, their violence after separation. This may be as an attempt to gain or reassert control over a victim survivor, or as punishment for leaving the relationship.

Measure: Number/proportion of family violence incidents where ‘recent or imminent separation’ is recorded

If a family violence incident involves current or former partners, police will record whether the couple recently separated.

In 2021–22, recent separation was recorded in one-third (32.2 per cent) of family violence incident reports.

The proportion of incidents where recent or imminent separation was recorded has remained stable since 2019–20 (between 31 and 32 per cent).

In 2019–20, Victoria Police introduced statewide changes to family violence recording practices through a new Risk Assessment and Risk Management report (L17). These changes to recording practices mean that it is not practical to compare data prior to 2019.

Footnotes

1 Campo M 2015, Children’s exposure to domestic and family violence: Key issues and responses, CFCA paper no. 36, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 5. https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/childrens-exposure-domestic-and-f…

2.2 Victim survivors are safe

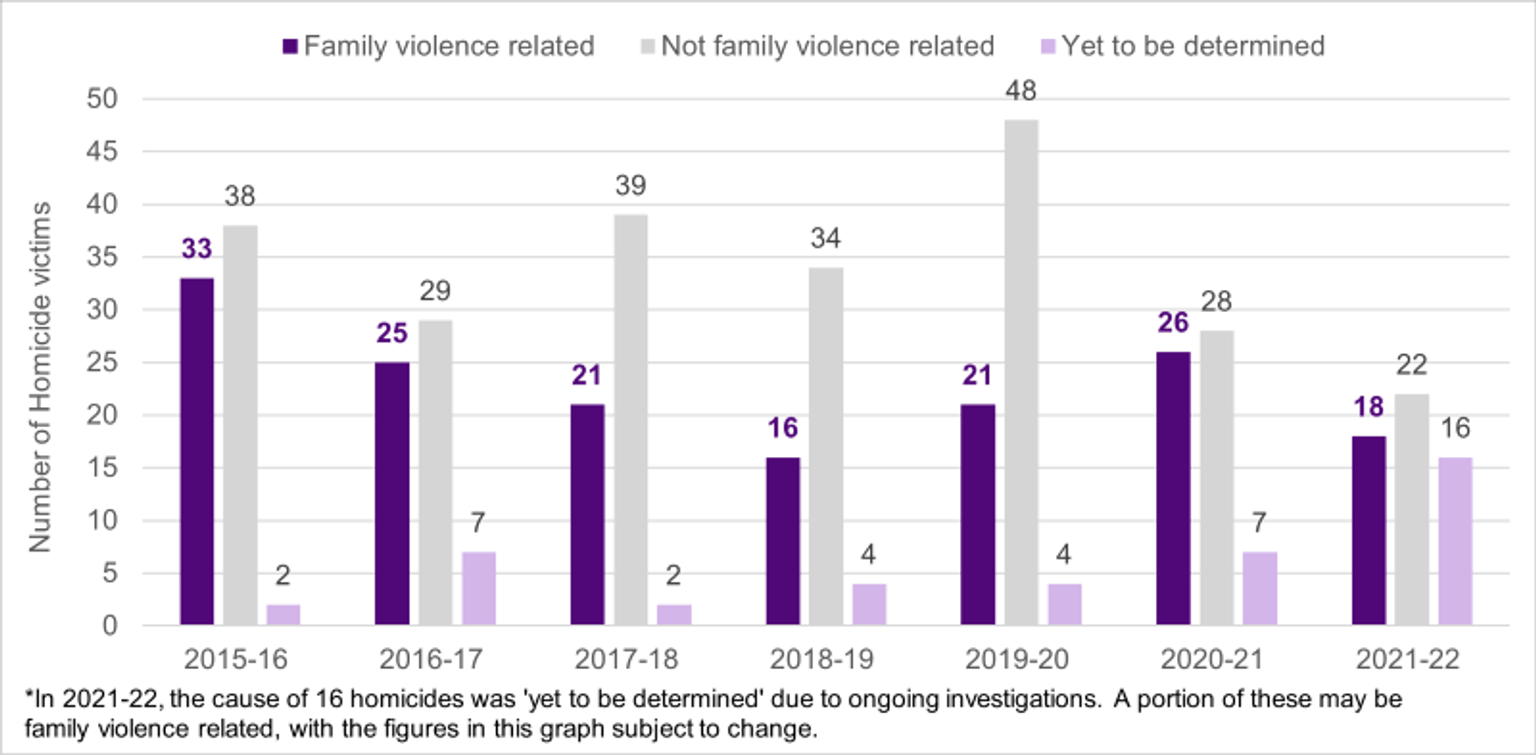

Indicator: Decrease in family violence deaths

Measure: Number of family violence-related deaths

Analysis of data over the past seven financial years indicates that the number of family violence homicides has not significantly decreased. However, 2015–16 had the highest number of family violence-related homicides over this period, with a lower number of homicides in every year since.

Most family violence related homicide victims are women and girls, representing 14 of the 18 victims in 2021–22.

The time lag between when a homicide is reported to the register and when an investigation concludes (and identifies whether a homicide was related to family violence) is the key reason for the higher number of ‘yet to be determined’ homicides in the two most recent years, as shown in Figure 1.

Table 1 provides Victorian data on the number and rate (per 100,000 people) of family violence related homicide victims from 2015–16 to 2021–22. While it may appear that family violence related homicides are decreasing, figures for 2021–22 are likely to increase as investigations into ‘yet to be determined’ homicides are finalised.

Table 1: Family violence related homicide victims - number and rate per 100,000

| Type of homicide victim | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of family violence related homicide victims | 33 | 25 | 21 | 16 | 21 | 26 | 18 |

| Family violence related victims - rate per 100,000 | 0.53 | 0.40 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.271 |

Source: Coroners Court of Victoria data extracted from the Victorian Homicide Register by the Crime Statistics Agency

Notes

1This figure is likely to change as more ‘yet to be determined’ homicides are finalised by investigations and the Coroner.

2.3 Victim survivors are heard and in control

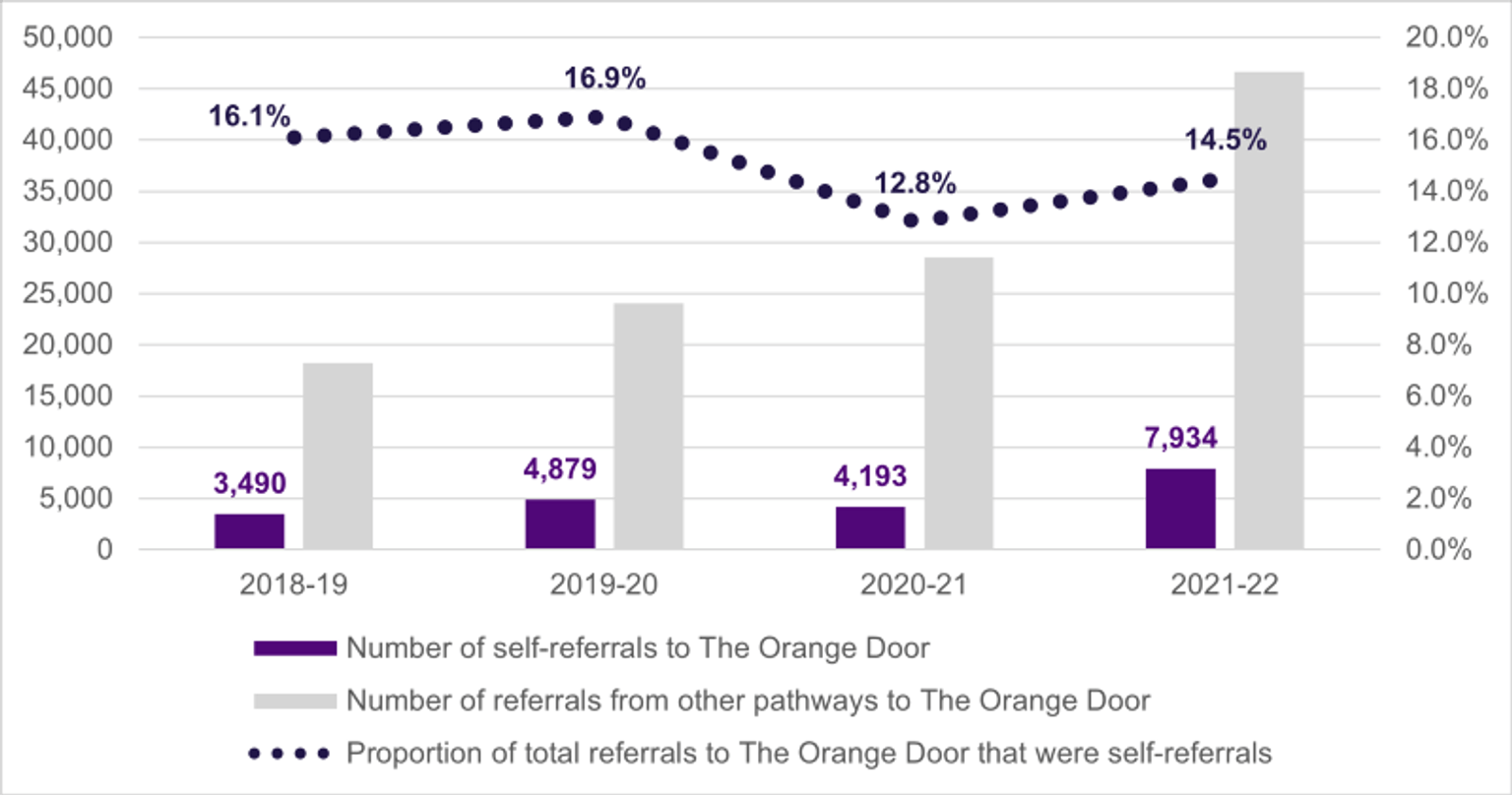

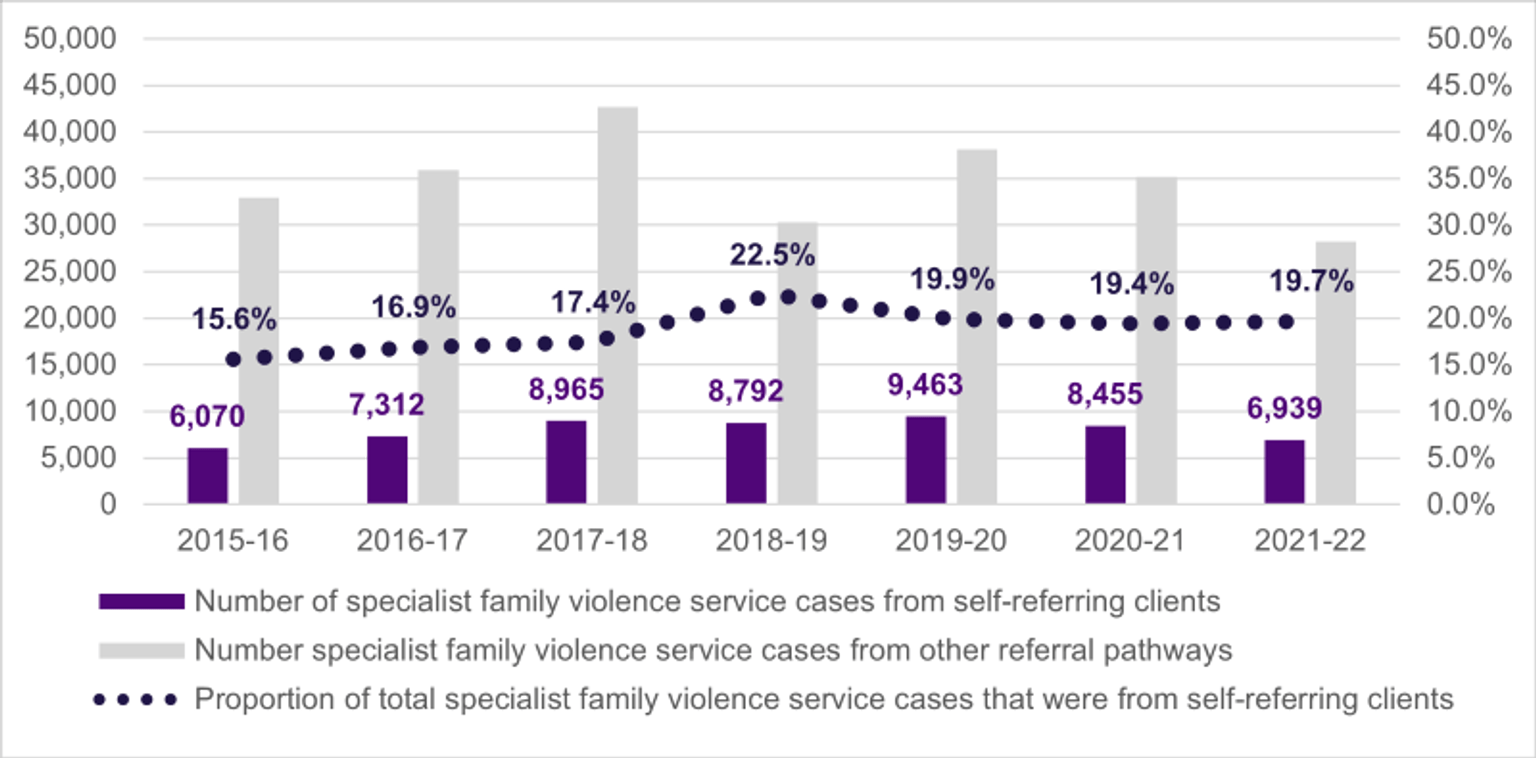

Indicator: Increase in self-referrals to family violence support services

A key principle of the family violence service system is that there is no wrong door for seeking support or advice. Referrals to family violence services or to The Orange Door can be made from police, a non-family violence service provider or a person experiencing violence and their family and friends. Self-referrals are one important way victim survivors can access support and get help when and where they need it, giving people choice in how they engage with the family violence service system.

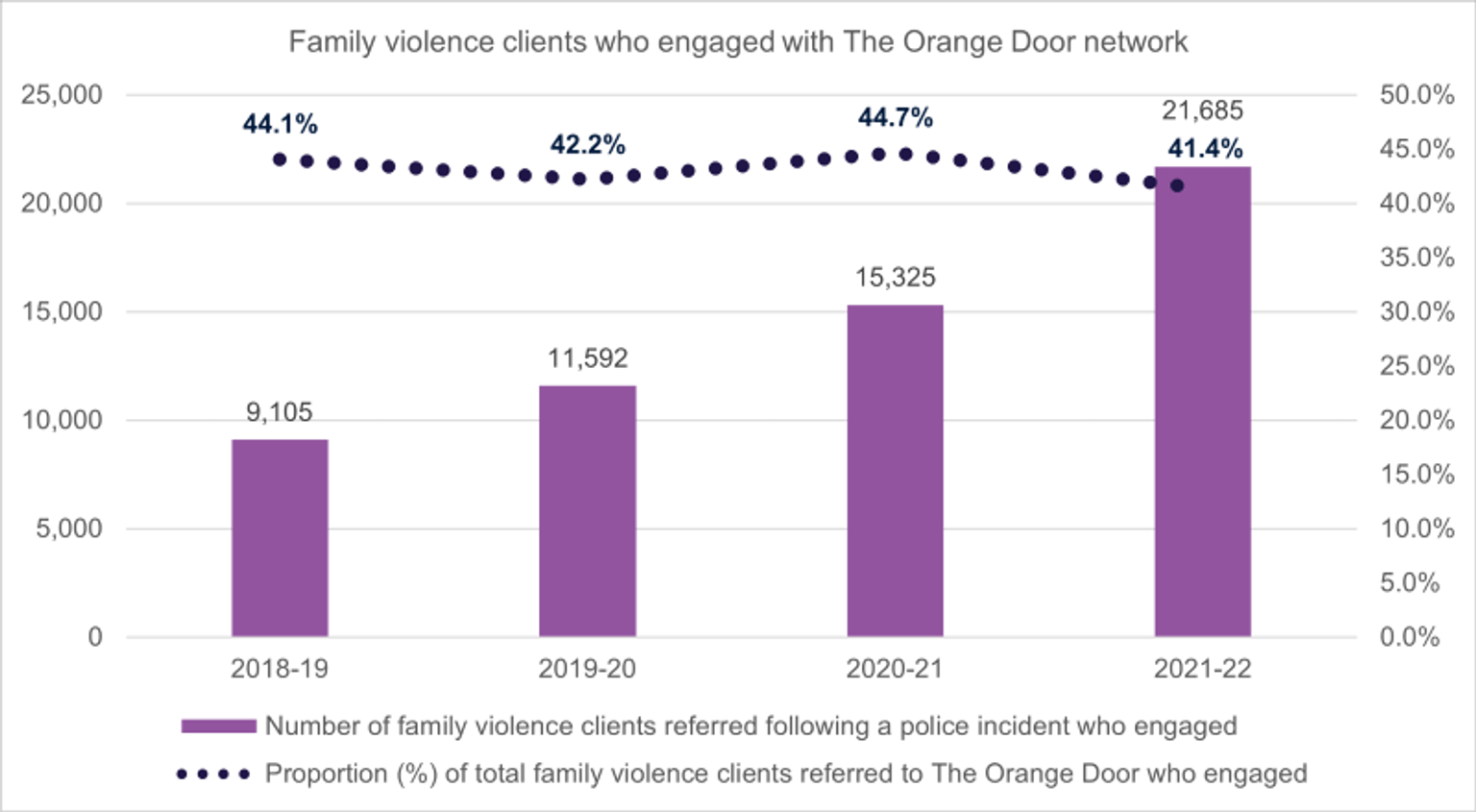

Measure: Number and proportion of self-referrals to The Orange Door network by victim survivors

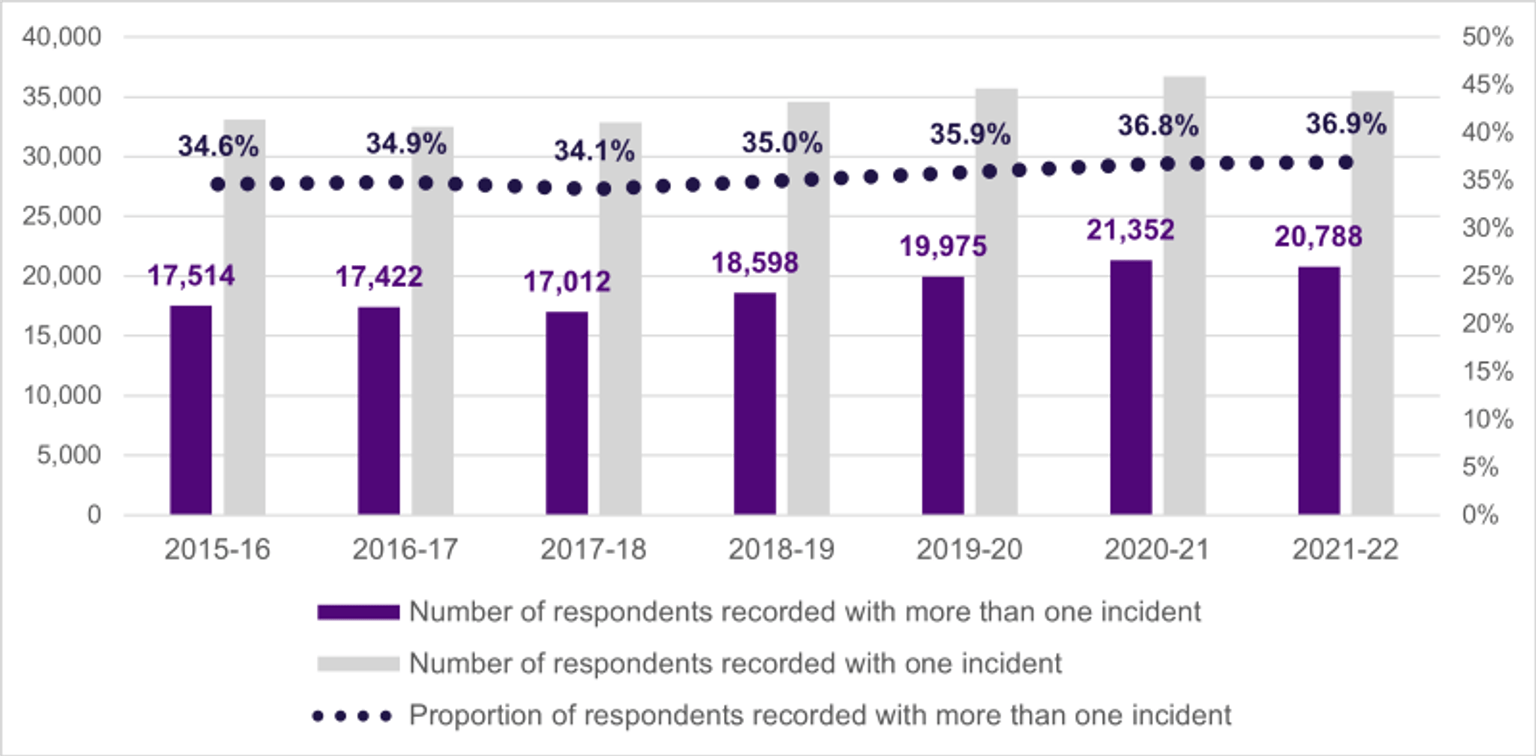

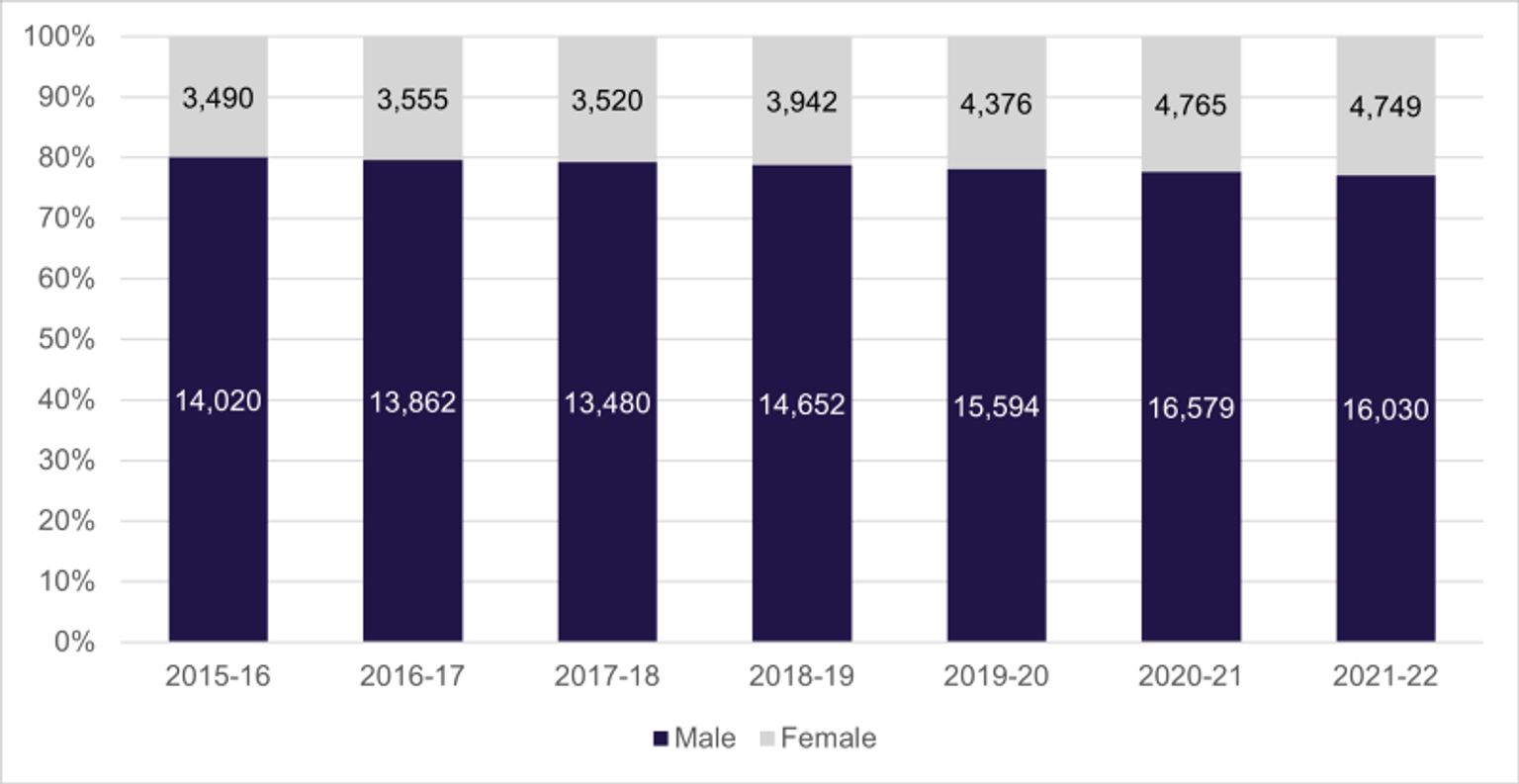

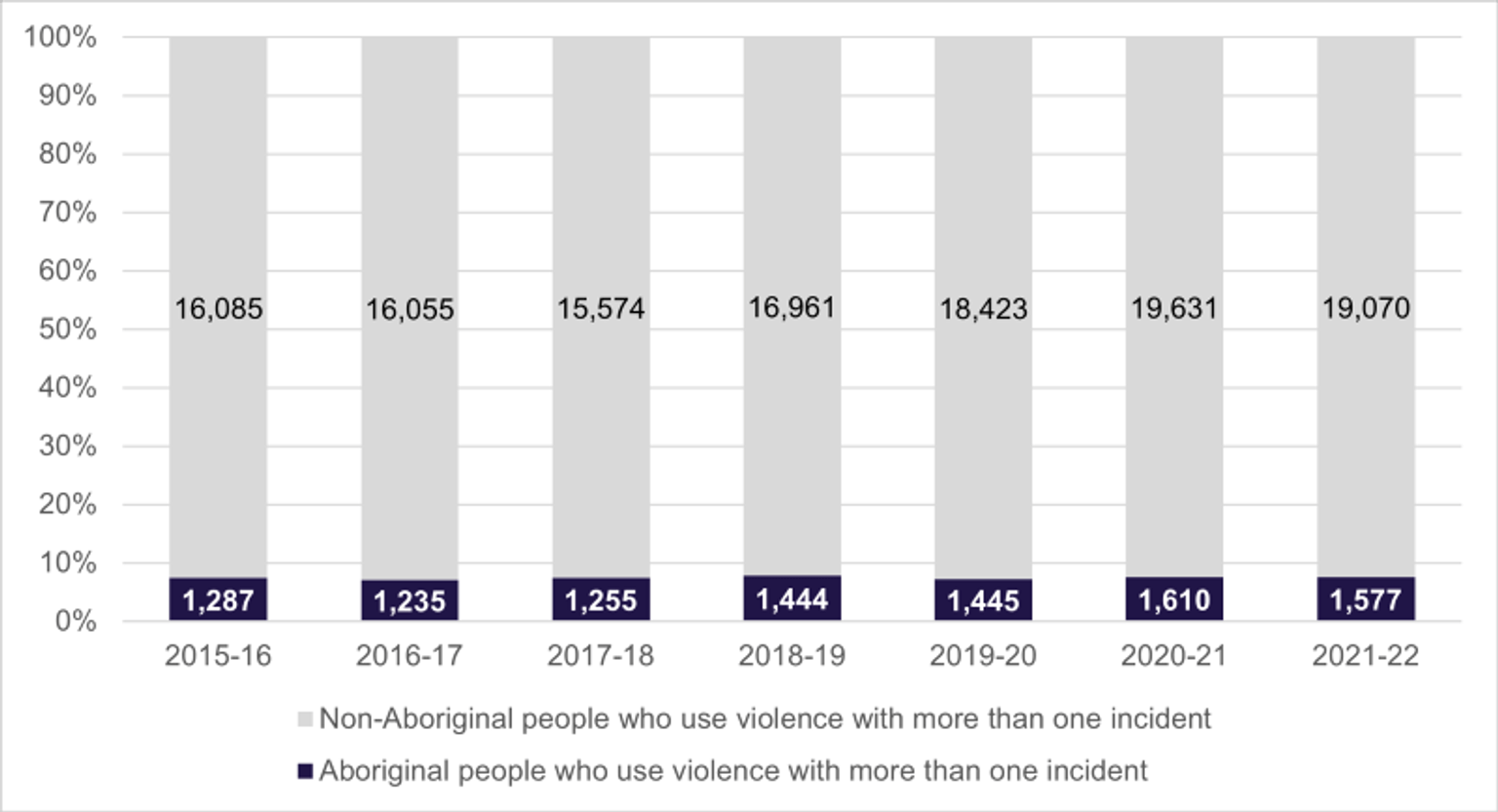

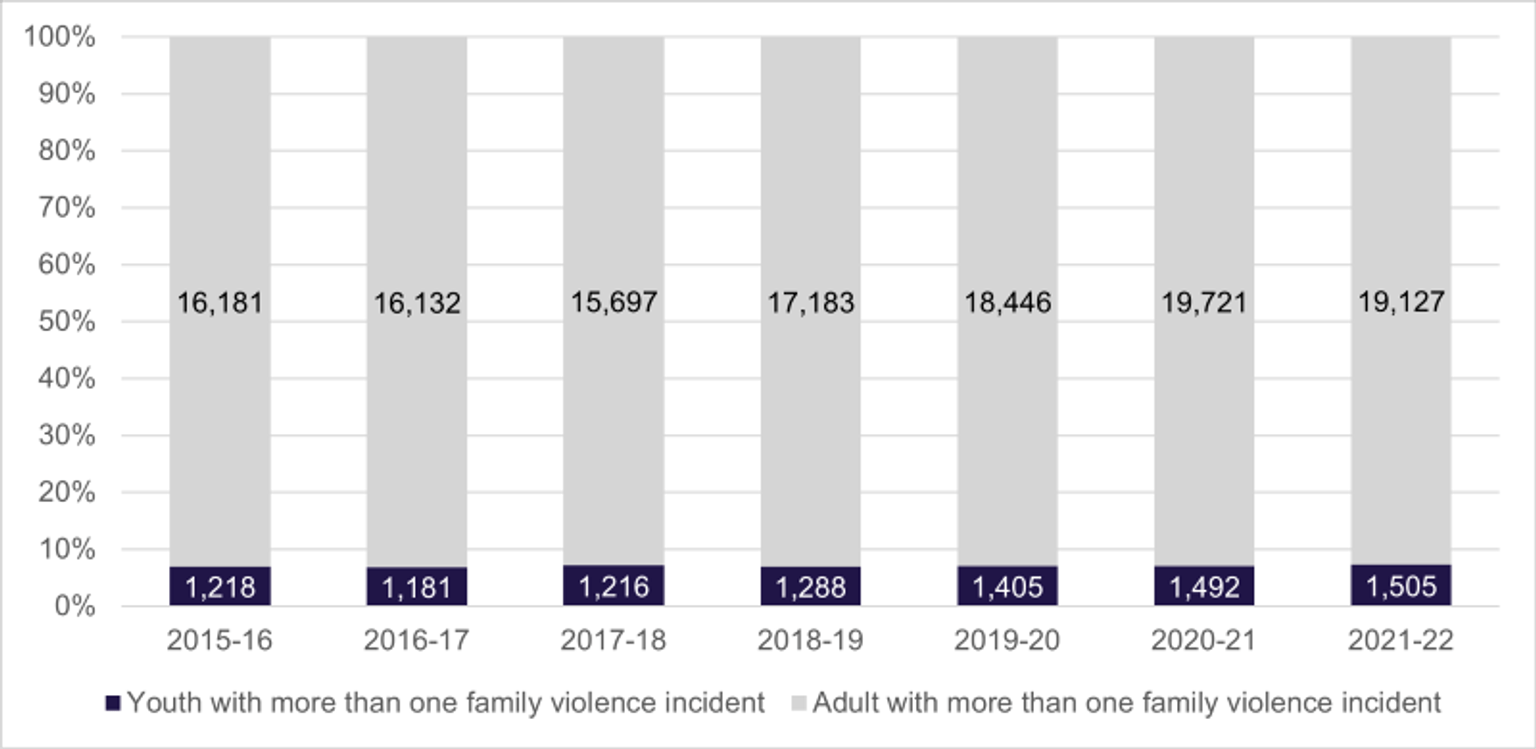

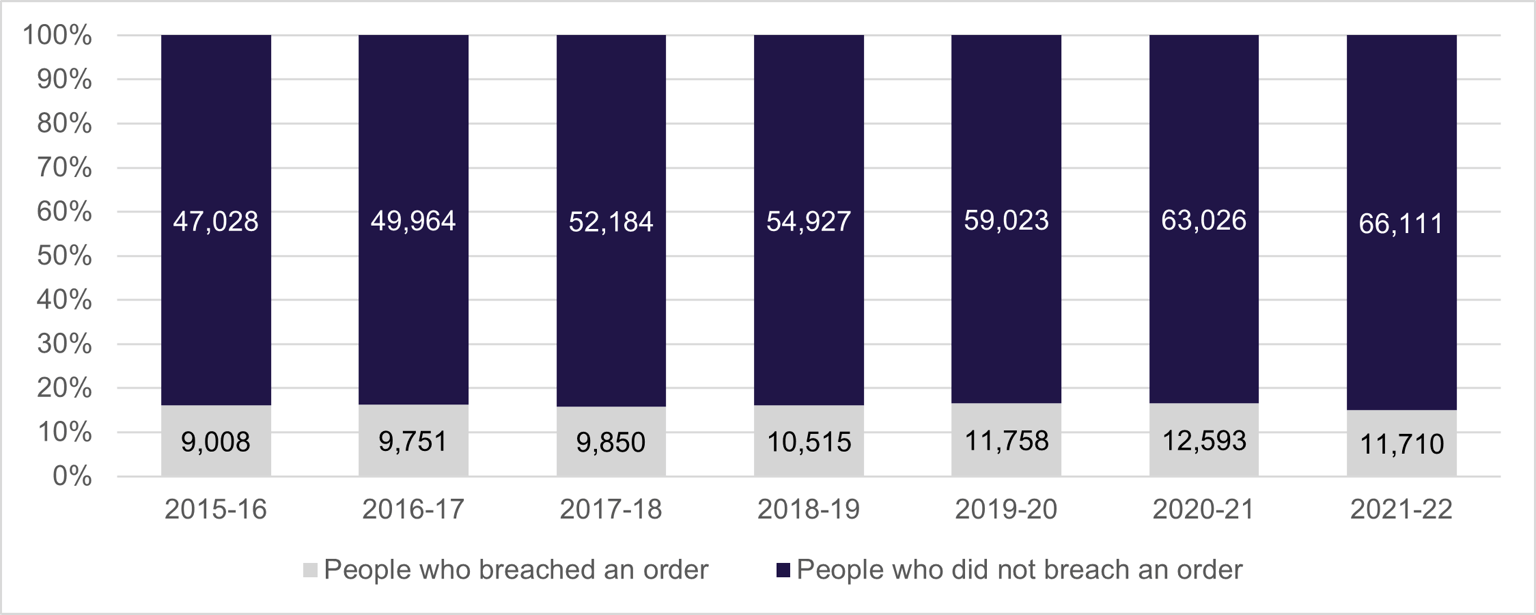

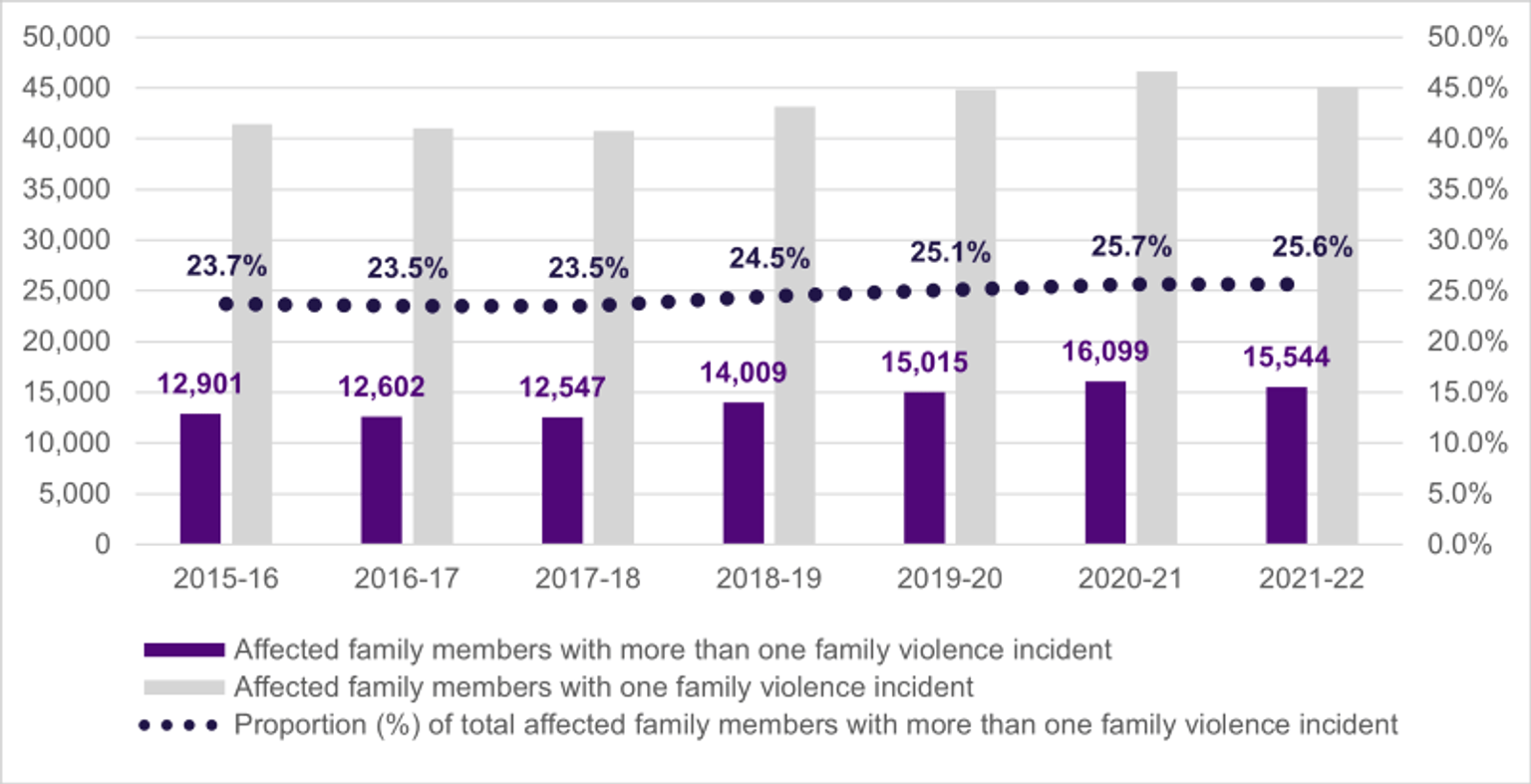

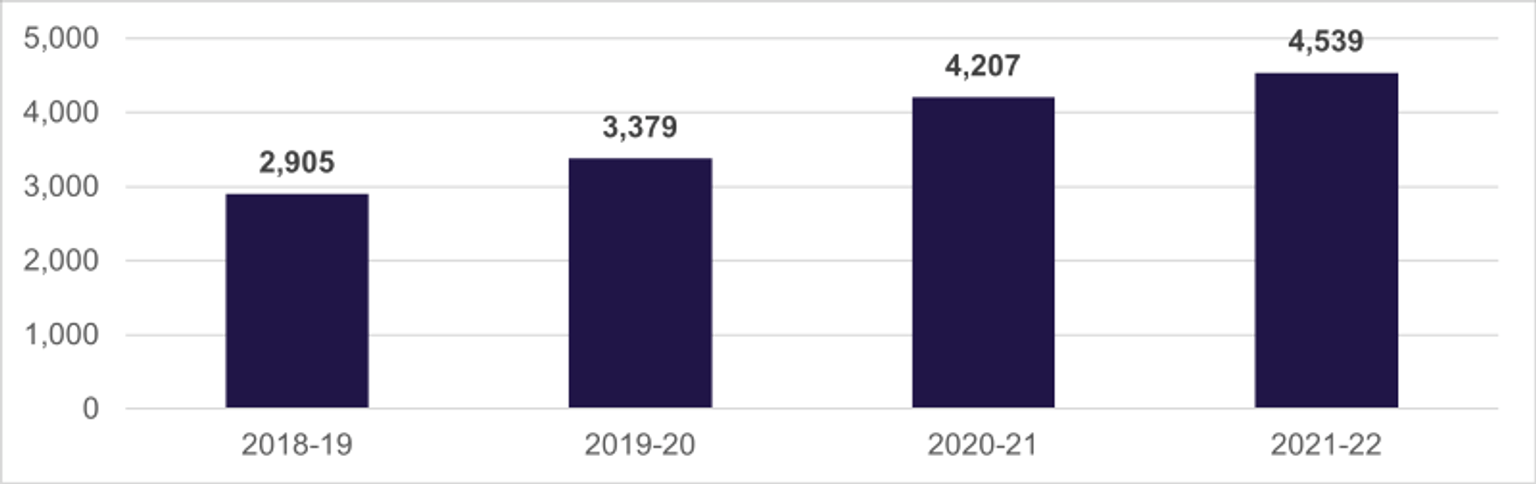

The number of self-referrals to The Orange Door network by victim survivors increased over the last four years. This is partly due to the progressive expansion of The Orange Door network over that period.