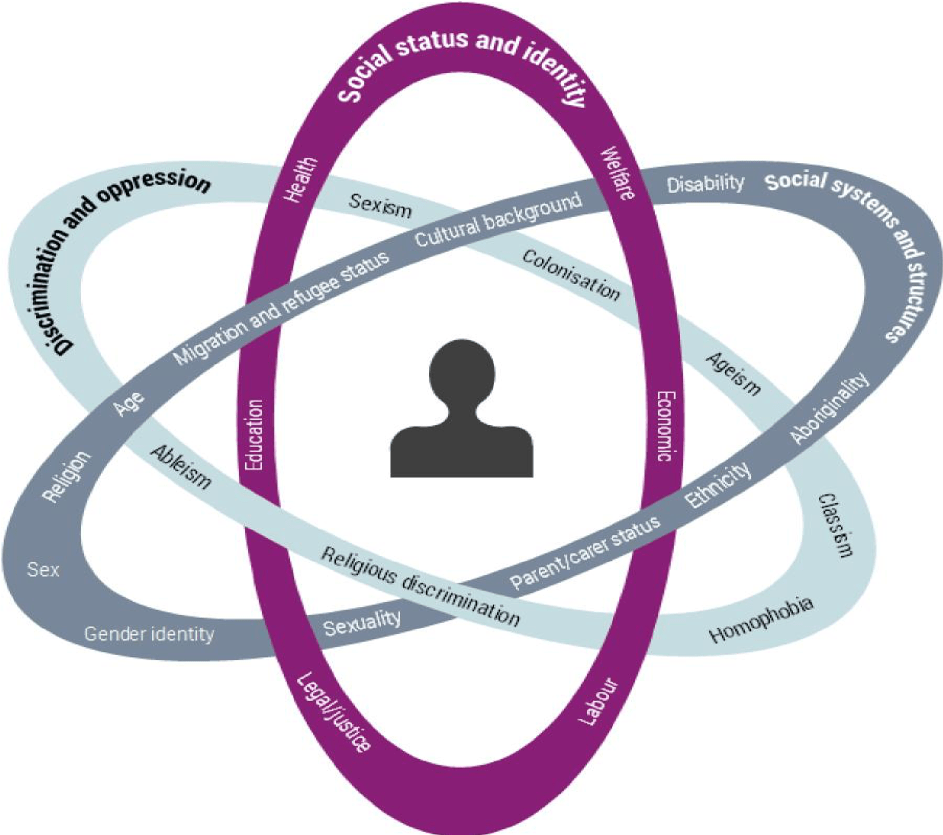

Many factors combine to form an individual’s identity and experience. While this framework has looked at priority communities in discrete sections, it should be noted that identity is complex and individuals should not be categorised based on one aspect of their identity. The Victorian Government’s Family Violence Diversity and Intersectionality Framework defines intersectionality as “different aspects of a person’s identity that can expose [that person] to overlapping forms of discrimination and marginalisation”.366 These aspects can include gender, class, ethnicity and cultural background, religion, disability and sexual orientation.367, 368

It is critical that family violence service providers and agencies adopt an intersectional approach. In the context of family violence, this means that services need to identify how the factors noted above can be associated with different sources of oppression and discrimination, and how those intersections can lead to increased risk, severity and frequency of experiencing different forms of violence.369 Services should appreciate the role that multiple sources of identity play in a person’s lived experiences, and be accessible, inclusive, non-discriminatory and responsive to the needs of diverse groups.

Due to the lack of existing administrative data concerning the priority communities discussed in this framework, minimal information is known about how diversity characteristics interact to compound the risk of family violence. However, some examples of how different aspects of a person’s identity can intersect to increase the risk of exposure to family violence have been outlined below. It is important to note that family violence is not part of any culture or unique to any specific community; however, the presence of power imbalances, discrimination and stigma experienced by diverse communities may heighten the risk of family violence.

Example 1. Gender inequality means that women are most at risk of experiencing family violence. The risk for women in diverse communities is exacerbated by intersecting social and institutional disadvantages, which create additional barriers to service access and disclosure. Aboriginal women are significantly more likely to be exposed to family violence and require hospitalisation for injuries than non-Aboriginal women, which may be explained by the intersection of race and gender-based discrimination and inequality.370

Example 2. Older people from CALD backgrounds who have recently migrated to Australia may experience social isolation, as they often lose their support networks through the process of relocation. They may also experience difficulties in accessing services, including facing language barriers, or having apprehension about contacting a mainstream service. As a result, older people from CALD backgrounds may become dependent on family members more fluent in English to meet their daily needs, which is problematic if these family members are responsible for perpetrating violence against them. Cultural norms and a fear of being ostracised from their family and community may prevent older CALD people from seeking help.371

Example 3. Children with disabilities are at increased risk of experiencing abuse, neglect and other forms of maltreatment, perpetrated by a parent or carer. Statistics on the victimisation of children with disabilities are limited, however, international studies have found that children with physical, sensory, intellectual and mental disabilities are twice as likely to experience violence than children that do not have disabilities.372

Example 4. Some CALD communities may hold more conservative views on gender and sexuality due to their cultural and religious backgrounds. These attitudes and beliefs may support or reinforce discrimination and violence against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people. The rejection of people on the basis of their sexuality or gender, and threats of ‘outing’ someone, may be used as a form of control and abuse within some CALD communities.373

Example 5. Disabilities disproportionately affect people over the age of 65. The care needs of older people with disabilities may place time and financial pressures on family members, and create tension or conflict within the home environment. Older people with disabilities are more vulnerable to abuse as a result of the accumulated risk associated with age-related disabilities or lifelong disabilities.374

In order to understand how family violence affects people in diverse communities, data needs to be reliably and consistently collected from the priority communities included in this framework. The collection of high quality, disaggregated data from these communities will not only enhance our understanding of the experiences of people from diverse groups, but will also provide information about the impact of family violence on people from intersectional backgrounds, and the unique risks and challenges that they face.

The framework can assist Priority 1: Building Knowledge from the Everybody Matters: Inclusion and Equity Statement (Everybody Matters)375 released in April 2019. Priority 1 focuses on research and data collection to fill gaps in current knowledge. Everybody Matters highlights the need to collect data around the unique experiences of people who access the service system from early intervention to response. The framework directly aids the fulfillment of this goal.

Modified from the Equality Institute 2017, and Our Watch 2017. 367, 377

366 State Government of Victoria, Diversity and Intersectionality Framework, viewed 22 June 2018, https://www.vic.gov.au/familyviolence/designing-for-diversity-and-intersectionality/diversity-and-intersectionality-framework.html

367. Ibid.

368. Frawley, P, Dyson, S, Robinson, S & Dixon, J 2015, What does it take? Developing informed and effective tertiary responses to violence and abuse of women and girls with disabilities in Australia, Landscapes: State of knowledge no. 3, ANROWS, Alexandria.

369. The Equality Institute 2017, Preventing and responding to family violence: Taking an intersectional approach to address violence in Australian communities, viewed 22 June 2018, www.equalityinstitute.org/family-violence-primary-prevention-in-victoria/

370. State of Victoria (Department of Premier and Cabinet) & the Equality Institute 2017, Family violence primary prevention: Building a knowledge base and identifying gaps for all manifestations of family violence, viewed 22 June 2018, https://www.vic.gov.au/system/user_files/Documents/fv/Family_Violence_Primary_Prevention%20-%20Building_a_knowledge_base_and_identifying_gaps_for_alll_manifestations_of_family_violence.pdf

371. Blundell, B B & Clare, M 2012, Elder Abuse in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Communities: Developing Best Practice, Centre for Vulnerable Children and Families: The University of Western Australia and Advocare Incorporated, Perth.

372. State of Victoria (Department of Premier and Cabinet) & the Equality Institute 2017, Family violence primary prevention: Building a knowledge base and identifying gaps for all manifestations of family violence, viewed 22 June 2018, https://www.vic.gov.au/system/user_files/Documents/fv/Family_Violence_Primary_Prevention%20-%20Building_a_knowledge_base_and_identifying_gaps_for_alll_manifestations_of_family_violence.pdf

373. Ibid.

374. Ibid.

375 Everybody Matters: Inclusion and Equity Statement, Viewed 17 April 2018, https://w.www.vic.gov.au/system/user_files/Documents/fv/Everybody%20Matters%20Inclusion%20and%20Equity%20Statement.pdf

376 The Equality Institute 2017, Preventing and responding to family violence: Taking an intersectional approach to address violence in Australian communities, viewed 22 June 2018, www.equalityinstitute.org/family-violence-primary-prevention-in-victoria/

377 Our Watch 2017, Intersectionality graphics, viewed 22 June 2018, https://www.ourwatch.org.au/getmedia/4135841b-76e8-4f11-88c4-76be0c8e12ae/Intersectionality-images.zip.aspx?ext=.zip

Updated