People with disabilities were recognised by the RCFV as a priority community affected by family violence. This section of the framework highlights the unique forms of family violence perpetrated against people with disabilities and the difficulties experienced responding to or reporting family violence incidents. It is noted that there are limitations which exist in current data standards, and that available administrative data concerning people with disabilities and their experiences of family violence are limited. This section contains data items recommended for use to ensure the consistent and accurate collection of disability information by organisations who respond to or provide services for family violence incidents.

Terminology and definitions

While there are many terms which can be used to describe people with disabilities, it is widely accepted that people-first language228 is favoured. However, there is some debate as to whether disability should be expressed in its singular or plural form.229 The framework will use the term ‘people with disabilities’, as this term is used in the RCFV report, and is recommended by the Judicial College of Victoria in their Disability Access Bench Book.230

Disability is a complex and evolving concept, and there is no standard definition of disability used across all government agencies and services. The DHHS Disability Action Plan 2018-2020231 defines people with disability as a diverse group, with a shared experience of encountering negative attitudes and barriers to full participation in everyday activities. The Disability Action Plan outlines that some conditions and impairments are present from birth and in other cases, people acquire or develop a disability during their lifetime from an accident, condition, illness or injury. The action plan acknowledges that some people are said to have dual disability. In their standard set of questions to capture information on disability, the AIHW defines disability as “a general term that covers:

- impairments in body structures or functions (for example, loss or abnormality of a body part)

- limitations in everyday activities (such as difficulty bathing or managing daily routines)

- restrictions in participation in life situations (such as needing special arrangements to attend work)”232

The AIHW definition informs national existing data standards for the collection of disability information, and this framework draws on those national standards.

| Legislative definitions of disability |

|---|

| State and Commonwealth legislation include various definitions of disability. These definitions range from broad (for example, the Equal Opportunity Act 2010 (Vic)) to specific (for example, the Guardianship and Administration Act 1986 (Vic)). Please note that this framework may not identify individuals who meet a specific legislative definition of disability. If an office or agency is required to identify people with disabilities in response to legislation which has a narrow definition of disability, they may need to collect additional information from clients beyond what is included in this standard to meet their specific internal needs. |

| How does mental illness relate to disability? |

|---|

| Psychosocial disability is a term used to describe individuals living with a disability that is associated with a severe mental illness.233 It is important to note that not all people with a mental illness will experience psychosocial disability,234 and although mental illness may overlap with experiences of disability, it is not often considered a disability in its own right. This section of the framework will discuss mental illness from the context of a psychosocial disability, and data items included in this standard only concern the collection of mental illness information where it is a source of disability. Agencies and service providers seeking to collect information on mental illness from a broader context than disability are encouraged to review existing national standards (for example, METeOR identifier: 399750 – Person identified with a mental health condition indicator).235 |

Family violence and people with disabilities

The RCFV report and research provides detailed information regarding what is known about the experiences of family violence faced by people with disabilities, and recommendations to address these issues. Summarised below are key points regarding the prevalence and issues stemming from family violence impacting this community.

Prevalence

Research and evidence presented to the RCFV suggested that people with disabilities are more often subjected to family violence compared with the general population. Although data in Australia are limited, research highlighted by the Australian Human Rights Commission found that nearly half of women with a disability surveyed in the UK reported having experienced domestic violence in their lives.236 In their research paper ‘Voices against Violence (paper 1)’, Women with Disabilities similarly acknowledged that international research indicates that women with disabilities are at a heightened risk of experiencing family and sexual violence compared to women without disabilities.237

The Human Rights Commission noted that a national survey of 367 family violence agencies found that approximately 22% of women and children accessing services were recorded as having a disability. While this number does not account for women with disabilities who do not access family violence services, it does support the position that this population is at a heightened risk for family violence victimisation in Australia.

Contributing circumstances and specific presentations of family violence risk

Family violence incidents are often understood to occur within relationships characterised by coercion, control and domination. It was noted by the RCFV that when perpetrators are in a position of power within a relationship, there is a higher occurrence of family violence.238 Due to social and environmental barriers, people with disabilities may more often be in a position of inequality with others, which in turn increases their risk of abuse. In their submission to the RCFV, the Office of the Public Advocate stated that “[w]hile women with disabilities experience many of the same forms of violence that other women experience, what they experience may be particular to their situation of disadvantage, cultural devaluation and increased dependency on others”.239

The RCFV found that when people with disabilities are dependent upon others for assistance they are:

- more likely to experience family violence240

- more likely to be abused by a wide range of perpetrators (including intimate partners, family members and caregivers)241

- more likely to be exposed to a wide range of abuses (including abuses which exploit a person’s need for assistance, such as withholding access to medication)242

- less likely to report family violence to others.243

Under-reporting and barriers to accessing services

Most crimes against people with disabilities go unreported, largely because of multifaceted barriers which prevent or discourage them from reporting crime.244 Under-reporting of family violence incidents involving people with disabilities is typically explained by the environmental, social and personal factors which impact a person’s decision to either not disclose incidents of family violence, or, when family violence is reported, to withhold information about their disability. In order to improve the quality of administrative data which exists in Victoria concerning people with disabilities impacted by family violence, barriers to reporting must be addressed.

Some of the reasons that people with disabilities may not disclose a family violence incident, or not access family violence services include:

- fear of discrimination or discriminatory treatment

- lack of knowledge about what constitutes family violence, who to report to and how the report can be made

- fear they will not be believed or viewed as credible

- fear that the abuse will be minimised or not taken as seriously as it should be

- reluctance to disclose stemming from past experiences of how people with disabilities have been treated by police and government agencies, including having been restrained or placed in involuntary care

- an inability to use oral or written language to communicate the details of a family violence incident in a way that is required by a person collecting data

- poor physical access to services, including building access restrictions, and limited phone and technology access

- concerns regarding the consequences of reporting. For example, if a person is physically dependent on the perpetrator, they may worry about that person being removed if no other care arrangement can be made. Similarly, if the person reports and nothing is done, the abuse may worsen.

Why do we need to collect information on disability?

The need to collect data on disability by family violence service providers and agencies was noted by the RCFV, with recommendation 170 stating that “the Victorian Government adopt a consistent and comprehensive approach to the collection of data on people with disabilities who experience or perpetrate family violence”.245 In Victoria, there is currently minimal available information on people with disabilities and their experience with family violence. Without adequate data on the subject, it is difficult to make informed decisions about service demand, intervention strategies and risk factors associated with future exposure to family violence.

Limited available data

A major concern highlighted by the RCFV was the absence of national level data which can be used to understand the prevalence of family violence impacting people with disabilities. One of the best sources of survey data in Australia concerning family violence is the ABS Personal Safety Survey (PSS). The PSS collects information from men and women aged 18 and older about the nature and extent of violence experienced since the age of 15. While the survey contains valuable information on family violence in Australia, a small sample size limits the amount of information which can be collected. The survey currently captures information about disability status in addition to intimate partner violence, stalking, emotional abuse and physical and sexual abuse, however it notably does not collect information about many forms of family violence disproportionately experienced by people with disabilities, including family violence that is perpetrated by parents, children, or familial-like individuals, such as carers. In addition, the PSS does not offer assistance for people with communications disabilities to complete the survey, so this population is excluded from the data collection. As such, it is difficult to get a full picture from this survey about the impact of family violence on people with disabilities.

There is also an absence of administrative data available concerning people with disabilities and their experience with family violence. It was found that the lack of existing data can largely be attributed to the significant barriers people with disabilities face when seeking to report family violence,246 and inadequate data collection practices employed by agencies and service providers.247 In order to improve the collection of data on people with disabilities, attention should be directed to both reducing the barriers that people with disabilities face when reporting an incident, and improving the practices used by agencies and services for collecting disability information.

Operational need to identify disability and provide reasonable adjustments

People with disabilities may face significant barriers which impact their ability to access an agency or service. Under the Equal Opportunity Act 2010 (Vic) there is a duty for organisations “to take reasonable, proportionate and proactive steps towards eliminating discrimination”.248 Organisations should therefore be actively identifying people with disabilities in order to fulfil an operational need to offer appropriate accommodations where required. Failure to provide such adjustments may be determined to constitute indirect discrimination against a person with a disability.

Indirect discrimination is described in the Equal Opportunities Act 2010 (Vic) to occur when: “a person imposes, or proposes to impose, a requirement, condition or practice –

(a) that has, or is likely to have, the effect of disadvantaging people with an attribute and

(b) that is not reasonable”.249

An example of indirect discrimination includes a requirement that all people, without exception, wishing to file a complaint or grievance must do so in writing. This indirectly discriminates against those who are unable to write.

Challenges in current data collection practices

In the 2017 ‘Australia’s Welfare’ report, the AIHW noted that most non-disability specific services in Australia do not collect information on whether a person has a disability.250 When these services include the option to collect disability information, very often the associated questions are either not asked or responses are not recorded.

There are a number of explanations for inconsistent collection of disability information by agencies and service providers in Victoria. The lack of a consistent definition of disability across Australia, and the fragmented structure of disability supports and services, present a problem for standardised and comprehensive reporting of disability data. The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), National Disability Agreement, and state governing bodies all provide definitions of disability.251 As a result, the scope and detail of disability information collected may not be consistent across services. In addition, different types of services will collect different information depending on what is most relevant for service provision. For example, medical services may be more likely to collect disability information by way of diagnoses and medical history, while non-disability specific services may be more interested in collecting information concerning support needs or a need for reasonable adjustments.

A further barrier for the collection of consistent data may be that people with disabilities are reluctant to disclose their disability to service providers. This is due in part to a history of discrimination, people may also feel a service will not be able to help them if they disclose their disability.

Organisational culture, training and policies also play a role in the absence of administrative data concerning people with disabilities and their experience with family violence. This can include that the collection of disability information is not seen as a core business function, or that staff are reluctant or unsure of how best to collect disability information for fear of causing offence.

Existing data standards

In recent years there has been a push to ensure that the needs of people with disabilities when interacting with services and programs in Australia are addressed. In particular, the National Disability Strategy (NDS) 2010-2020 encourages improvements in performance by non-disability specific services in delivering outcomes for people with disabilities. A key first step in ensuring that services are more responsive to the needs of people with disabilities is to reliably and consistently identify individuals who may require accommodations. Additionally, the NDS recognises that “[g]ood data and research are especially necessary for a sound evidence base to improve the effectiveness of mainstream systems for people with disability”.252 As a result, there has been a national movement towards the creation and adoption of a standardised collection method to be used by services nationally to produce reliable and comparable data concerning people with disabilities.

Australian Bureau of Statistics

The Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC)

Currently, the main survey used by the ABS to collect information on disability in Australia is the Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC) which is designed to collect “information about the wellbeing, functioning and social and economic participation of people with disabilities in Australia”.253 The SDAC collects a comprehensive range of information about people with disabilities, but the level of detail and number of questions included in the survey is higher than what would be practical for use in an administrative setting.

The Supplementary Disability Survey (SDS)

In 2016, the ABS trialled a Supplementary Disability Survey (SDS), which is a short set of disability questions designed by the Washington Group on Disability Statistics, a branch of the United Nations Statistical Commission. This set of questions is known as the Washington Group Short Set, and was created to address an urgent need for internationally comparable data on disability.

The questions focus on limitations and impairments experienced in six domains. For each domain, respondents are asked to identify the level of impairment they face. The domains and impairment levels are described in the tables below.

| Domains |

|---|

| (1) Seeing |

| (2) Hearing |

| (3) Walking |

| (4) Cognition |

| (5) Self-care |

| (6) Communication |

| Measurement of difficulty |

|---|

| (a) No difficulty |

| (b) Some difficulty |

| (c) A lot of difficulty |

| (d) Cannot do at all |

Advantages of the SDS are that it is an internationally comparable standard, and it was designed with brevity, simplicity, and an ability to identify individuals with disabilities from a broad range of nationalities and cultures. However, the ABS found that the results of the SDS did not provide comprehensive information on disability, were not comparable with the SDAC, and the questions were not suitable for identifying intellectual or psychological disabilities or young children with disabilities.254

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Standardised Disability Flag Module

In 2012-13, the AIHW was tasked to design a short set of questions to be used nationally by all nondisability specific services to identify individuals with a long-term health condition or disability who report an activity limitation, a specific education participation restriction and/or a specific employment participation restriction.

The AIHW standardised disability flag module (the flag)255 (METeOR Identifier: 521050) is based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, a classification of health domains put forward by the World Health Organisation, and is also consistent with surveys used by the ABS for collecting information on disability. It is intended for use across a wide range of sectors, enabling nationally consistent collection of information used to identify people with disabilities or long term health conditions who experience difficulties or need assistance in various areas of their life.

The flag’s questions can fit into an organisation’s typical process of collecting administrative data, whether this be the completion of a digital or paper form, or by staff interviewing a client or their proxy. The flag is comprised of three groups of questions:

- activity and participation need for assistance cluster (METeOR identifier: 505770)

- education participation restriction indicator (METeOR identifier: 520889)

- employment participation restriction indicator (METeOR identifier: 520912)

The flag is comprised of 10 mandatory questions which fall into one of the above groups. Responses concerning activity participation and need for assistance consist of eight questions which are recorded on a four point scale, ranging from ‘have no difficulty’ to ‘always/sometimes need help or supervision’. Questions concerning education and employment participation restrictions are asked separately and require a yes/no response.

Activity and participation need for assistance cluster (METeOR identifier: 505770)256

These questions are about whether you have any long-term health conditions or disabilities. A longterm health condition is one that has lasted, or is expected to last, 6 months or more. Examples of long-term health conditions that might restrict your routine activities include severe asthma, epilepsy, mental illness, hearing loss, arthritis, depression, autism, kidney disease, chronic pain, speech impairment or stroke.

| Choose one answer for each row | Always sometimes need help or supervision | Have difficulty but don’t need help and/or supervision | Don’t have difficulty but use aids/equipment/medication | Have no difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-care e.g. showing or bathing; dressing or undressing; toileting; eating food. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Mobility e.g. moving around the house; moving around outside the home; getting in or out of a chair; using public transport. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Communication e.g. understanding or being understood by other people, including people you know; using a telephone. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Managing things around the home e.g. getting groceries; preparing meals; doing washing or cleaning; taking care of pets. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Managing tasks and handling managing time; planning activities; coping with pressure or stressful situations. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Personal relationships e.g. making friends; meeting new people; showing respect to others; coping with feelings and emotions. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Community life e.g. participating in sports, leisure or religious activities; being part of a social club or organisation. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Education participation restriction indicator (METeOR identifier: 520889)257

|

The next question is about whether a long-term health condition or disability affects your participation in education, including school or another educational institution (such as TAFE, university, or skills centre). Participation in education is considered to be affected if you:

Does a long-term health condition or disability affect your participation in education? □ Yes |

Employment participation restriction indicator (METeOR identifier: 520912)258

|

The next question is about whether a long-term health condition or disability affects your participation in work. Participation in work is considered to be affected if you:

Does a long-term health condition or disability affect your participation in work (paid and/or volunteering)? □ Yes |

Applying data standards to the collection of disability information in a family violence context

While standards exist in Australia for the collection of disability information in the context of particular administrative collections by mainstream organisations and in the collection of survey data, there is no standard designed specifically for mainstream agencies who are collecting information in response to a family violence incident. Services and agencies who respond to family violence can be considered distinct from many other organisations in that they are often interacting with people in a crisis situation who may be experiencing extreme distress or an immediate need for service. In these circumstances, asking a number of questions about a person’s disability or daily limitations may not always be realistic or practical. It is however important information to establish in order to know how to appropriately respond to the person experiencing the family violence. Although the AIHW flag is recommended for use as the national standard for collecting information on disability, an abridged set of disability questions is also presented in this section for agencies and services who cannot practically implement the AIHW flag.

Data collection standard for collecting disability information

When collecting information about disability it is recommended that data collectors explain why the information is being collected, and ask if the client is comfortable answering questions about their health or disability. If a disability is disclosed, this should signal that a direct service response or referral to an appropriate service may be required.

It is recommended that service providers and agencies ask a person if they would like assistance to answer questions. This may include having a support person who can assist them (provided that this person is not the perpetrator or known by the perpetrator).

This data collection standard may have limitations for collecting information from certain people including those from different cultural backgrounds or experiences, or people with cognitive disabilities. Staff collecting information using this standard should therefore be mindful of the information being collected, including what it will be used for and when the collection methods should be altered to adjust for people who are from different cultures or have unique communication needs. More information can be found under ‘Considerations when implementing data items’ on page 81.

Agencies and services should note that questions about disability and health information are considered to be private information, and relevant privacy legislation, including the Health Records Act 2001 (Vic) and the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 (Vic) should be considered by data custodians when collecting and storing this information. Information concerning privacy and security considerations is discussed on page 18.

Overview of data collection standard

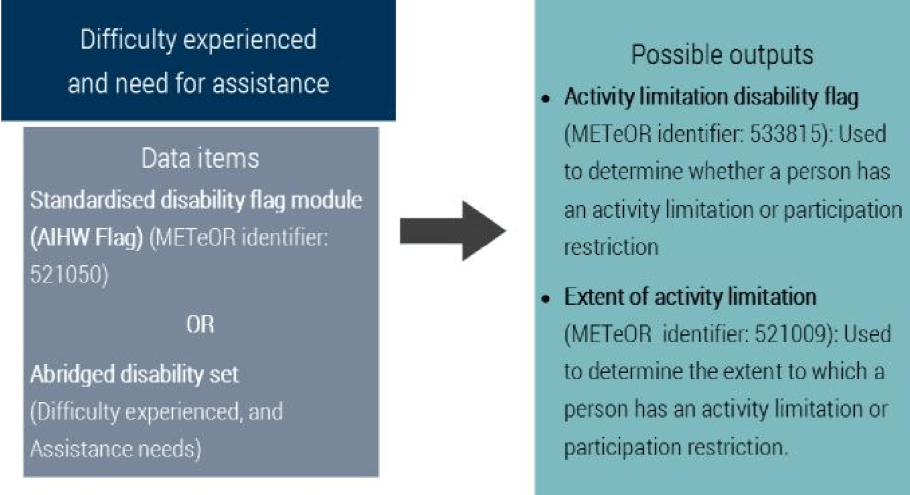

The disability standard proposed in this framework contains two components; ‘difficulty experienced and need for assistance’ and ‘disability group’. These two components contain data items which can be used to derive METeOR outputs. Agencies and services can use these outputs to identify whether a person has an activity limitation, the extent of their limitation, and to provide information about the disability group.

Difficulty experienced and need for assistance

This component collects information on difficulty experienced by a person and their need for assistance with employment, education and routine activities. This information can be gained either through use of the AIHW flag, or through the abridged disability set. Responses from either of these data collection sets can be used to derive METeOR data items as outputs, which provide information on whether a person experiences an activity limitation or participation restriction, and the extent of this limitation or restriction.

Disability group

This question asks respondents which response option(s) best describe the group(s) responsible for an impairment of body structure or function, limitation in activity or restriction in participation. Outputs from this component will provide more details about a person’s experience of disability, and may be used to flag for conditions which are of interest for research purposes, including acquired brain injuries.

Abridged disability set

Where it is not practicable for a service or agency to use the AIHW flag, the abridged set of questions below is recommended. These two questions relate to the difficulty experienced by an individual and their assistance needs.

Difficulty experienced – Question phrasing and response categories

|

Because of a long-term health condition, mental illness or disability lasting or expected to last 6months or longer, do you experience any difficulty or restriction which affects your participation in activities at work, school1 or when doing routine tasks2? □ Yes 1. School refers to a range of educational institutions, including University, TAFE and other learning centres. 2. Routine tasks include bathing, dressing, eating, moving around the house or outside the home, communicating with others, making decisions, learning new things, preparing meals, managing daily routine, caring for children or others, coping with stress, making new friends or socialising with others. |

Assistance needs – Question phrasing and response categories

|

Because of a long-term health condition, mental illness or disability lasting or expected to last 6 months or longer, when at work, school or doing routine tasks, which of the following options best describes your need for assistance? □ Always/sometimes need help or supervision |

Using and interpreting responses

The ‘difficulty experienced’ and ‘assistance needs’ questions should be collected together in order for agencies and services to gather meaningful information about a person’s experience of disability or activity limitation. The results of these questions may be mapped to METeOR outputs. For information on how these response options can be mapped, please see ‘How to map responses from the abridged disability set to METeOR data items’ on the following page.

Disability group

This data item has been modified from the AIHW Disability group code (METeOR identifier: 680763).259 The advantage of using this question is that it captures additional information on disability, which is important for research and evaluation purposes. For instance, the RCFV identified that people with acquired brain injuries were a priority for research efforts concerning family violence, with current available information indicating that this group may be at an increased risk for using and experiencing family violence.

For this data item, the option to select multiple categories is strongly recommended. It is noted that some data collection systems may not be able to currently accommodate for multiple categories to be selected, however it is encouraged that service providers look into options for collecting multiple responses for disability group. People with disabilities often have comorbid conditions and may find it difficult to choose only one category which primarily causes impairments to their routine activities. If it is not possible to allow individuals to select multiple categories of disability, respondents should be asked to select the category which primarily causes the most difficulty for them in daily life.

It should be noted that this data item is not suitable for use on its own to collect information about disability. This question should be used in combination with the AIHW flag or the abridged disability set in order to collect information about disability.

Question phrasing and response categories

|

Do you have a long-term health condition or disability which can be described under the following categories? □ Intellectual (including Down syndrome) |

Using and interpreting responses

Responses from this data item can be used in combination with the previous data items used to collect information about the difficulty a person experiences and their need for assistance in order to provide detailed information about a person’s experience of disability.

When collecting data verbally, information and guidance should be provided to assist a respondent in understanding the response categories. Definitions can be found in the glossary at the end of this section.

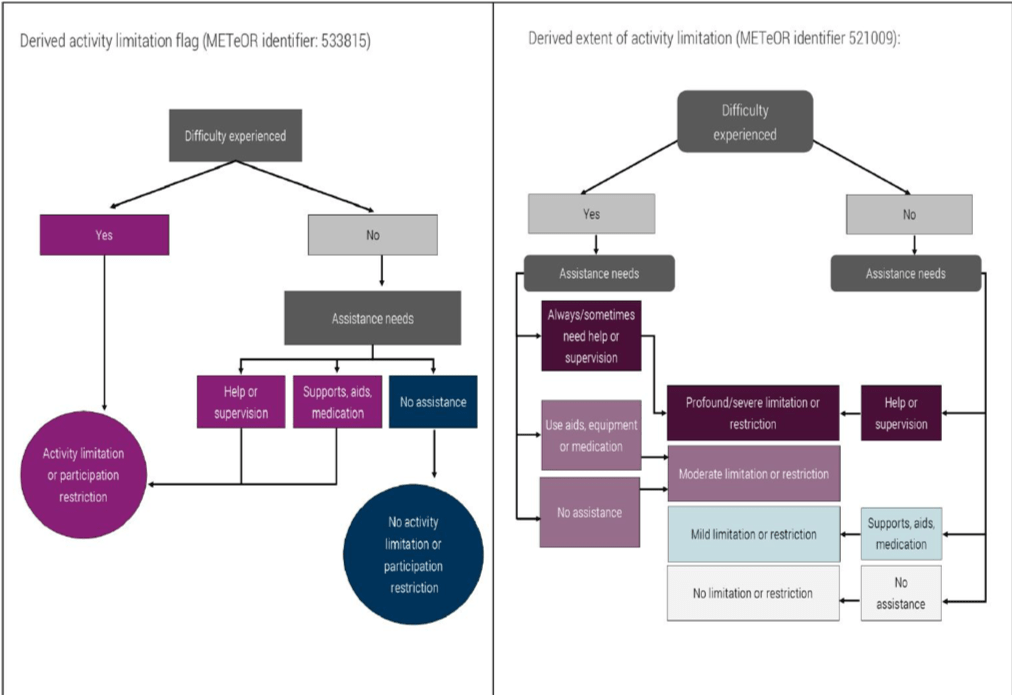

How to map responses from the abridged disability set to METeOR data items

If an agency or service uses the abridged disability set rather than the AIHW flag, responses can be mapped to existing METeOR data items. The following figure describes how responses from the abridged disability set can be used to derive the response options included in the METeOR data items ‘derived activity limitation flag’, and ‘derived extent of activity limitation.’

Reasonable adjustment question [optional but recommended]

Although this question is not part of the data collection standard and will not directly capture information about disability, it is recommended for use by service providers, particularly when clients or respondents have disclosed that they face difficulties on account of a disability. Organisations in Victoria are obligated under the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) and the Equal Opportunity Act 2010 (Vic) to provide reasonable adjustments when needed for people with disabilities to access their services.

As many services will have ongoing communication with people accessing their services, this question asks if any adjustments need to be made regarding how an organisation communicates with a client. A service or agency should also ask other questions about reasonable adjustments which are specific to the services that they provide, for example, whether someone requires mobility assistance. The Australian Human Rights Commission’s factsheet ‘Access for all: improving accessibility for consumers with disability’ is a good resource for agencies or services looking to improve accessibility for people with disabilities.260

|

How should we communicate with you? □ Verbal communication |

Considerations when implementing data items

Data collectors should be mindful when questioning people with certain communication needs or people from different cultural backgrounds, that additional discussion may be needed to gain accurate information about disability. Administrative collection of disability information typically involves organisations asking close-ended questions about a person’s health and functioning. While this method is ideal for generating easily reportable data, it may present problems when collecting information from certain audiences. The following information highlights population groups who may benefit from the use of alternative wording or collection methods when asking about disability information, and the proper terminology to use when discussing concepts surrounding disability.

People who require assistance to communicate

People with disabilities who have difficulty communicating are especially at risk of not reporting incidents of family violence, largely because of the communication barriers they face when attempting to seek help. If an agency or service provider finds that they cannot communicate with a person with a disability through their normal business communication practice, then they should explore other methods which can be used to communicate with that person. Service providers should also be mindful to offer multiple communication options for people with disabilities when collecting information, including offering options for verbal communication, written communication, or communicating through an agreed third party.

People with a cognitive disability or need for easy English

Cognitive disability is a term used to describe a wide variety of impaired brain functions including impairment in comprehension, reasoning, adaptive functioning, judgement, learning or memory that

is the result of any damage to, dysfunction, developmental delay, or deterioration of the brain or mind.261 Cognitive disability can be used to incorporate a number of conditions, such as intellectual disability, acquired brain injuries, autism and dementia. People with a cognitive disability may have difficulty learning and recalling skills, following instruction, recognising cause and effect, or performing physical and cognitive tasks. Part of providing a more accessible service for people with a cognitive disability may include the use of easy English. Easy English is specifically designed to make sense to people who have difficulty reading and understanding English. It is a style of writing that is simple and concise, focuses on presenting key information rather than the detail, and uses a mix of words and images to enhance the message for the reader.262 Style guides and fact sheets can be found on the Scope website, www.scopeaust.org.au/service/accessible-information/.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

People from Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander communities may require alternative wording or additional conversation surrounding the concepts of disability, mental illness or medical conditions. While Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander views on disability vary between different people, environments and cultures, there are some general concepts which may be relevant to discussions surrounding disability data collection by service providers. In their report entitled ‘Cultural Proficiency in Service Delivery for Aboriginal People with a Disability’, the NDS noted several barriers which may impact a person of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin from disclosing disability information. These include:263

- In certain traditional Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander cultures, people with medical conditions or physical impairments are not viewed as distinct from the general population. Individuals from these communities may not have comparable concepts to assist with understanding disability as it is viewed in a Western context.

- Many people of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin experience discrimination, and may therefore be reluctant to have a second label applied to them which can be further prone to discrimination or discriminatory treatment.

- Some traditional Aboriginal communities view disability as a consequence of being ‘married the wrong way’. In these cases, disability may be a source of stigma or shame related to a ‘bad karma’ view of disability.

Additionally, the First Peoples Disability Network have emphasised that health for Aboriginal peoples focuses not only on physical health, but also encompasses spiritual, cultural, emotional and social wellbeing.264 Health is therefore more than the absence of sickness, but involves the relationship with family and community, providing a sense of belonging and connection with the environment. This holistic definition of health varies from how disability is defined in the disability data collection standard used in the framework, and therefore responses gained from data collection may not represent how Aboriginal people view their own health and wellbeing.

If any of the above barriers appear to be relevant when questioning an Aboriginal person about disability information, it may be more useful to have an open-ended discussion about a person’s routine life activities and needs for assistance, rather than relying on close-ended questions about disability.

People from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds

It was revealed during consultation with service providers that people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds may benefit from alternative wording or additional conversation surrounding the concepts of disability, mental illness or long-term medical conditions. In particular it was noted that recent immigrants to Australia and people with limited English may experience difficulty understanding complex questioning around their health, or their ability to perform routine tasks. Additionally, in some circumstances refugees and new immigrants to Australia may not have had much exposure to Westernised medical care, making it less likely for these people to have received a recognised medical diagnosis. As such, they may be unaware if they have a condition which would be considered a source of disability. Finally, it was noted that many cultures outside of Australia do not have comparable concepts around disability and mental illness, and questions about these concepts may be confusing or offensive. In these cases, open ended discussions may be beneficial in making a determination about a person’s need for assistance.

People with a psychosocial disability

As this data collection standard was designed to capture information about a wide range of disabilities, the wording used in the data items may not be intuitive to trigger the disclosure of a psychosocial disability, particularly in cases where a condition is episodic. When appropriate, data collectors can employ alternative wording when asking about disability status. This can involve explaining that a condition can be something that causes a person difficulty for certain periods of time, and not necessarily something that is experienced daily, or at a constant level of severity.

Inclusive language

When describing disability, language that respects all people as active individuals with control over their own lives should be used. Negative language, such as ‘suffers from depression’, ‘afflicted with Multiple Sclerosis’ or ‘confined to a wheelchair’, should be avoided,265 and neutral phrases like ‘person experiencing depression’ or ‘person who uses a wheelchair’ should be used instead. As mentioned at the beginning of this section, using person-first language, for example, ‘people with disabilities’ is also preferred to outdated and offensive terms like ‘disabled person’, ‘bi-polar person’, ‘handicapped’ or ‘the disabled’.266 This language reinforces the notion that the term disability describes the barriers that a person faces when engaging with their environment, and it does not define the characteristics of an individual. ‘Training and resources’, at the end of this section, outlines organisations in Victoria and nationally that provide advocacy, information, training and assistance for agencies or service providers working with people with disabilities.

Training and resources

Training and communication resources

Australian Sign Language Interpreters’ Association Victoria

The Victorian professional body for Auslan interpreters.

Website: www.asliavic.org.au

Email: info@asliavic.com.au

Beyond Blue

Provides information and support to help everyone in Australia achieve their best possible mental health. They can provide special resources and training for schools, workplaces, aged care and health professionals.

Website: www.beyondblue.org.au

Phone: 03 9810 6111

Communication Rights Australia

Communication Rights Australia provides advocacy and professional independent communication support worker (ICS) services.

Website: www.communicationrights.org.au

Phone: 03 9555 8552

Disability Advocacy Resource Unit

Provides training and resources to keep disability advocates informed and up to date about issues affecting people with disabilities in Victoria.

Website: www.daru.org.au

Phone: 03 9639 5807

Disability Justice Advocacy

Advocacy support for people with a disability in Victoria.

Website: www.justadvocacy.com

Phone: 03 9474 0077

Scope

Information and communication support services for people with complex communication needs. Scope can assist with developing communication aids and Easy English materials.

Website: www.scopevic.org.au

Phone: 1300 472 673

VicServ

The peak body for mental health services in Victoria.

Website: www.vicserv.org.au

Phone: 03 9519 7000

Victorian Mental Illness Awareness Council

The peak Victorian non-government organisation for people with lived experience of mental health or emotional issues. Part of their role is to provide education to the community about mental illness from the consumer perspective, and they engage in educational activities for service providers who work in clinical and community support sectors.

Website: www.vmiac.org.au

Phone: 03 9380 3900

Disability information and advocacy bodies

Amaze

Information about autism spectrum disorder.

Website: www.amaze.org.au

Phone: 03 9657 1600

Blind Citizens Australia

Information about people who are blind or have low vision.

Website: www.bca.org.au

Phone: 1800 033 660

Cerebral Palsy Support Network

Information about people with cerebral palsy.

Website: www.cpsn.org.au

Phone: 03 9478 1001

Down Syndrome Victoria

A membership organisation providing parents, families, professionals and friends of people with Down Syndrome with support, information and resources.

Website: www.downsyndromevictoria.org.au

Email: info@dsav.asn.au

First Peoples Disability Network

A peak organisation representing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living with disability.

Website: www.communicationrights.org.au

Phone: 03 9555 8552

Headspace

The National Youth Mental Health Foundation provides early intervention mental health services to 12-25 year olds, along with assistance in promoting young peoples’ wellbeing. Information and services for young people, their families and friends as well as health professionals can be accessed through their website, Headspace centres, online counselling service eheadspace, the Digital Work and Study Service and postvention suicide support program headspace School Support.

Website: www.headspace.org.au

Phone: 03 9027 0100

Mind Australia

One of the country’s leading community-managed specialist mental health service providers, supporting people dealing with the day-to-day impacts of mental illness, as well as their family, friends and carers.

Website: www.mindaustralia.org.au/about-mind

Phone: 1300 286 453

Sane

Support and information about mental health disabilities.

Website: www.sane.org

Helpline: 1800 18 7263

VicDeaf

Information and services for people who are deaf or hard of hearing and individuals and organisations working with people who are deaf or hard of hearing, including Auslan interpreting services.

Website: www.vicdeaf.com.au

Phone: 03 9473 1111

Vision Australia

A national provider of blindness and low vision services.

Website: www.visionaustralia.org

Phone: 1300 84 74 66

Women with Disabilities

Information and advocacy for women with disabilities.

Website: www.wdv.org.au

Phone: 03 9386 7800

Glossary

Activity: Describes the execution of one or more tasks that a person may need to perform as part of their daily life. Can include cognitive, emotional, communication, health care, household chores, meal preparation, mobility, property maintenance, reading or writing, self-care or transportation related tasks.

Activity limitations: Difficulties an individual may have in executing activities, which may vary with the environment. Activity is limited when an individual, in the context of a long-term health condition or disability, either has a need for assistance in performing an activity in an expected manner, or cannot perform the activity at all.267

Disability: Disability is a complex and evolving concept, and there is no standard definition. AIHW defines it is a general term that covers impairments in body structures or functions (for example, loss or abnormality of a body part), limitations in everyday activities (such as difficulty bathing or managing daily routines) or restrictions in participation in life situations (such as needing special arrangements to attend work).268 The DHHS disability Plan 2018-19 defines people with a disability as a diverse group with a common shared experience of encountering negative attitudes and barriers to full participation in everyday activities.269

Impairments: Problems in body function or structure such as organs, limbs and their components.270

Mental health problem: Describes the broad range of features that interfere with how a person thinks, feels and behaves, but to a lesser extent than a mental illness. A person experiencing poor mental health therefore may not meet diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder, but may still experience a negative impact on their life.271

Mental illness: A clinical diagnosable illness that significantly interferes with an individual’s cognitive, emotional or social ability. The diagnosis of mental illness is generally made according to the classification systems of the ‘Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders’ (DSM) or the ‘International classification of diseases’ (ICD).272

Psychosocial disability: A disability arising from a mental health issue.273

Reasonable adjustment: A modification made to the provision of a service in order to assist a person with an impairment to participate, access or derive benefit from that service. When determining whether an adjustment is reasonable or not, consult section 45(3) of the Equal Opportunities Act 2010 (Vic).

| Disability group |

|---|

|

The list below provides definitions for the response categories used in the ‘disability group’ data item on page 79. Intellectual: Applies to conditions appearing in the developmental period (0-18 years) and is associated with impairments of mental functions, difficulties in learning and performing certain routine activities, and limitations with adaptive skills in the context of community environments when compared with others of the same age. This category includes Down syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, Specific learning: Refers to learning disorders, including Attention Deficit Disorder, other than intellectual.275 Autism: Includes Asperger’s syndrome and Pervasive developmental delay.276 Physical: Used to describe conditions that are attributable to a physical cause or impact on the ability to perform physical activities, such as mobility. Physical disability often includes impairments of the neuromusculoskeletal systems including the effects of paraplegia, quadriplegia, muscular dystrophy, motor neuron disease, neuro muscular disorders, cerebral palsy, absence or deformities of limbs, spina bifida, arthritis, back disorders, ataxia, bone formation or degeneration and scoliosis.277 Acquired brain injury: Used to describe multiple disabilities arising from damage to the brain acquired after birth. Damage can result in deteriorated cognitive, physical, emotional or independent functioning. Causes include blunt force trauma, strokes, brain tumours, infection, poisoning, lack of oxygen and degenerative neurological disease.278 Neurological: Applies to impairments of the nervous system occurring after birth, and includes epilepsy and organic dementias (for example, Alzheimer’s disease), as well as conditions such as multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease.279 Deafblind (dual sensory): Refers to a dual sensory impairment associated with severe restrictions in communication and participation in community life. Deafblindness is not just vision impairment with a hearing loss, or a hearing loss with a vision impairment. Deafblindness is a unique disability of its own requiring distinct communication and teaching practices.280 Vision: Encompasses blindness and vision impairment (not corrected by glasses or contact lenses), which can cause severe restriction in communication and mobility, and in the ability to participate in community life.281 Hearing: Encompasses deafness, hearing impairment and hearing loss.282 Speech: Encompasses speech loss, impairment and/or difficulty in being understood.283 Psychosocial: Includes an experience of disability associated with a mental illness.284 |

228 People-first language emphasises the person first, and not the disability. For example, using ‘person with a disability’, rather than ‘the disabled’.

229 People with Disability Australia 2017, Terminology used by PWDA, viewed 21 June 2018, www.pwd.org.au/studentsection/terminology-used-by-pwda.html

230 Judicial College of Victoria and VEOHRC 2016, Disability Access Bench Book, viewed 21 June 2018, www.judicialcollege.vic.edu.au/disability-access-bench-book

231 DHHS Disability Action Plan 2018-2020, https://dhhs.vic.gov.au/publications/disability-action-plan-2018-2020

232 AIHW Metadata Online Registry, Standardised disability flag module, viewed 21 June 2018, http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemld/521050

233 National Mental Health Consumer & Carer Forum (NMHCCF) 2011, Unravelling Psychosocial Disability, A Position Statement by the National Mental Health Consumer & Carer Forum on Psychosocial Disability Associated with Mental Health Conditions, NMHCCF, Canberra, p.9.

234 Ibid.

235 AIHW Metadata Online Registry, Person – formally diagnosed mental health condition indicator, code N, viewed 21 June 2018,

http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemld/399750

236 Ibid p.29.

237 Woodlock, D, Healey, L, Howe, K, McGuire, M, Geddes, V & Granek, S 2014, Voices Against Violence Paper One: Summary Report and Recommendations, Women with Disabilities Victoria, Office of the Public Advocate and Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria.

238 RCFV 2016, Volume 5 Report and recommendations, p.177.

239 Office of the Public Advocate 2015, Submission to the Victorian Royal Commission into Family Violence, no. 905, p.10, viewed 22

June 2018, www.rcfv.com.au/Submission-Review

240 RCFV 2016, Volume 5 Report and recommendations, p.177.

241 Ibid p.173.

242 Ibid.

243 Ibid p.183.

244 VEOHRC 2014, Beyond doubt: The experiences of people with disabilities reporting crime – Research findings, viewed 21 June 2018, www.humanrightscommission.vic.gov.au/our-resources-and-publications/reports/item/894-beyond-doubt-the-experiences-ofpeople-with-disabilities-reporting-crime.

245 RCFV 2016, Volume 1 Report and recommendations, p.90.

246 RCFV 2016, Volume 5 Report and recommendations, p.172.

247 VEOHRC 2014, Beyond doubt: The experiences of people with disabilities reporting crime – Research findings, viewed 21 June 2018, www.humanrightscommission.vic.gov.au/our-resources-and-publications/reports/item/894-beyond-doubt-the-experiences-ofpeople-with-disabilities-reporting-crime

248 VEOHRC, Positive duty, viewed 21 June 2018, www.humanrightscommission.vic.gov.au/home/the-law/equal-opportunity-act/positiveduty#what-is-the-positive-duty

249 Ibid.

250 AIHW 2017, Australia’s Welfare 2017, Australia’s welfare series no. 13, AIHW, Canberra, p.39.

251 Ibid.

252 Commonwealth of Australia 2011, National Disability Strategy 2010-2020, viewed 21 June 2018, www.dss.gov.au/ourresponsibilities/disability-and-carers/publications-articles/policy-research/national-disability-strategy-2010-2020

253 ABS 2016, 4430.0 Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings, 2015, viewed 21 June 2018,

http://abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/4430.0Main%20Features202015?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=4430.0&issue=2015&num=&view

254 ABS 2016, 4450.0 Supplementary Disability Survey, 2016, viewed 21 June 2018, www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4450.0

255 The AIHW Data Collection Guide for use of the standardised disability flag module can be downloaded at www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=60129557264

256 AIHW Metadata Online Registry, Activity and participation need for assistance cluster (disability flag), viewed 21 June 2018,

http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemld/505770

257 AIHW Metadata Online Registry, Person – education participation restriction indicator, code N, viewed 21 June 2018,

http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemld/520889

258 AIHW Metadata Online Registry, Person – employment participation restriction indicator, code N, viewed 21 June 2018,

http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemld/520912

259 AIHW Metadata Online Registry, Disability group code N[N], viewed 21 June 2018, http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemld/680763

260 Australian Human Rights Commission 2016, Access for all: Improving accessibility for consumers with disability, viewed 21 June 2018, www.humanrights.gov.au/employers/good-practice-good-business-factsheets/access-all-improving-accessibility-consumers

261 Smith, M 2017, ‘Communicating effectively with people with cognitive disability’, paper presented at the Council of Australasian

Tribunals Conference, viewed 21 June 2018, http://www.coatconference.com.au/resources/Melinda%20Smith%20-%20PRESENTATION.pdf

262 Scope, Accessible Information and Easy English, https://www.scopeaust.org.au/service/accessible-information

263 National Disability Services 2014, Cultural Proficiency in Service Delivery for Aboriginal People with a Disability, viewed 21 June 2018, www.idfnsw.org.au/images/A_Guide_to_Cultural_Proficiency_in_Service_Delivery_for_Aboriginal_People_-_Information.pdf

264 First Peoples Disability Network Australia 2016, Intersectional Dimensions on the Right to Health for Indigenous Peoples – A Disability Perspective, http://www.disabilityjustice.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Intersectional-Dimensions-on-the-Right-to-Health-for-Indigenous-Peoples---A-Disability-Perspective-FPDN.pdf

265 Judicial College of Victoria and VEOHRC 2016, Disability Access Bench Book, viewed 21 June 2018, www.judicialcollege.vic.edu.au/disability-access-bench-book

266 Ibid.

267 Ibid.

268 AIHW Metadata Online Registry, Standardised disability flag module, viewed 21 June 2018, http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemld/521050

269 DHHS Disability Action Plan 2018-2020, https://dhhs.vic.gov.au/publications/disability-action-plan-2018-2020

270 World Health Organisation 2018, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), viewed 21 June 2018,

www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/

271 Department of Health, National Mental Health Policy 2008: Glossary, viewed 13 June 2018, www.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-pubs-n-pol08-3

272 National Mental Health Consumer & Carer Forum (NMHCCF) 2011, Unravelling Psychosocial Disability, A Position Statement by the National Mental Health Consumer & Carer Forum on Psychosocial Disability Associated with Mental Health Conditions, NMHCCF, Canberra, p.6.

273 National Disability Insurance Agency, Psychosocial disability, viewed 21 June 2018, ndis.gov.au/psychosocial/products

274 AIHW Metadata Online Registry, Disability group code N[N], viewed 21 June 2018, http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemld/680763

275 Ibid.

276 Ibid.

277 Ibid.

278 National Disability Services, Disability Types and Description, viewed 21 June 2018, www.nds.org.au/disability-types-anddescriptions

279 Ibid.

280 AIHW Metadata Online Registry, Disability group code N[N], viewed 21 June 2018, http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemld/680763

281 Ibid.

282 Ibid.

283 Ibid.

284 National Disability Insurance Agency, Psychosocial disability, viewed 21 June 2018, www.ndis.gov.au/psychosocial/products

Updated