- Published by:

- Department of Education

- Date:

- 2 Sept 2024

The Information Sharing and Family Violence Reforms – Guidance and Tools is designed to support education workforces to:

- implement the Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS) and Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS) in their workplaces

- share information confidently, safely, and appropriately to improve children’s and families’ wellbeing and safety, and manage family violence risk

- meet their responsibilities under the Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM)

- identify and respond to family violence in a safe and consistent way and make better reports and referrals.

Introduction

About this resource

This resource is intended to support schools and services, system and statutory bodies, and education health, wellbeing, and inclusion workforces to:

- implement the Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS) and Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS) in their workplaces

- share information confidently, safely, and appropriately to improve children’s and families’ wellbeing and safety, and manage family violence risk

- meet their responsibilities under the Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM)

- identify and respond to family violence in a safe and consistent way and make better reports and referrals.

CISS, FVISS and MARAM are collectively known as the Reforms in this resource. This resource is for:

- long day care, kindergarten and before and after school hours care services (referred to as services in this resource)

- government, Catholic and independent schools (referred to as schools in this resource)

- Catholic and independent system bodies that assist, manage, or govern schools in Victoria (referred to as system bodies in this resource)

- Victorian Institute of Teaching, Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority, and Victorian Registration and Qualifications Authority (referred to as statutory bodies in this resource)

- some education health, wellbeing, and inclusion workforces (for example, Department of Education’s Health, Wellbeing, and Inclusion Workforces).

This resource is divided into 4 audience-based sections:

- Introduction

- School and service leaders

- All staff

- Staff who use CISS and FVISS

- MARAM nominated staff.

It also includes the following resources:

- Tools

- Staff supports and other resources.

How to use this resource

Each section of this resource provides tailored guidance to reflect the different roles and responsibilities of staff at your school or service. You may need to read one or more sections depending on your role.

You can download all tools and templates from this publication.

All schools and services must ensure all tools and templates are stored in a secure location that can only be accessed by relevant staff, such as school and service leaders, MARAM nominated staff and authorised staff.

You must also follow all data security and record management requirements that apply to your school or service. For more information, please see How do I keep records? in the MARAM nominated staff section.

Training and support

The Department of Education (the department) offers a range of learning options on the Reforms for schools and services, system and statutory bodies, and education health, wellbeing, and inclusion workforces. This includes webinars, eLearning modules and face-to-face training.

For more information see Training for the information sharing and MARAM reforms.

If you have any further questions about CISS, FVISS and MARAM, or this resource, including support with implementation, contact the Enquiry Line:

- Email: cisandfvis@education.vic.gov.au

- Phone: 1800 549 646 from 9 am to 5 pm Monday to Friday.

Staff wellbeing support

Supporting children and families who are experiencing wellbeing and safety concerns, including family violence, can be highly stressful and challenging. Given the reported prevalence of family violence, there is also a high likelihood you may know or be someone who has experienced or is experiencing family violence.

Staff wellbeing is a shared responsibility between you, your team and your organisation.

It is important to be aware of the impacts that supporting people experiencing family violence can have on you. Signs of vicarious trauma and burnout include experiencing intrusive thoughts of a victim survivor’s situation or taking on too great a sense of responsibility. These are common responses to the challenges of this type of work.

This resource addresses issues of family violence. If you are concerned for your safety or that of someone else, contact the police, and call 000 for emergency assistance.

If you have experienced violence or sexual assault and require immediate or ongoing assistance, contact 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) to talk to a counsellor from the National Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence hotline. For confidential support and information, contact Safe Steps 24/7 family violence response line on 1800 015 188.

If you need to talk to someone it is recommended that you speak to your leadership team about arranging appropriate support. You can also talk to your GP or an allied health professional. Victorian government school staff can also contact the Department of Education’s Employee Wellbeing Support Services on 1300 291 071.

For more information, see Staff supports and other resources.

Overview of the Information Sharing and Family Violence Reforms

As educators, carers and health, wellbeing, and inclusion professionals, you share a common purpose – to give each child the best start to a happy, healthy, and prosperous life. The wellbeing and safety of children is essential for their learning and development, and you are well placed to support them.

CISS, FVISS and MARAM (the Reforms) build on and complement your existing child and family wellbeing and safety responsibilities and practices. The Reforms aim to improve the wellbeing and safety of Victorian children, and to reduce family violence.

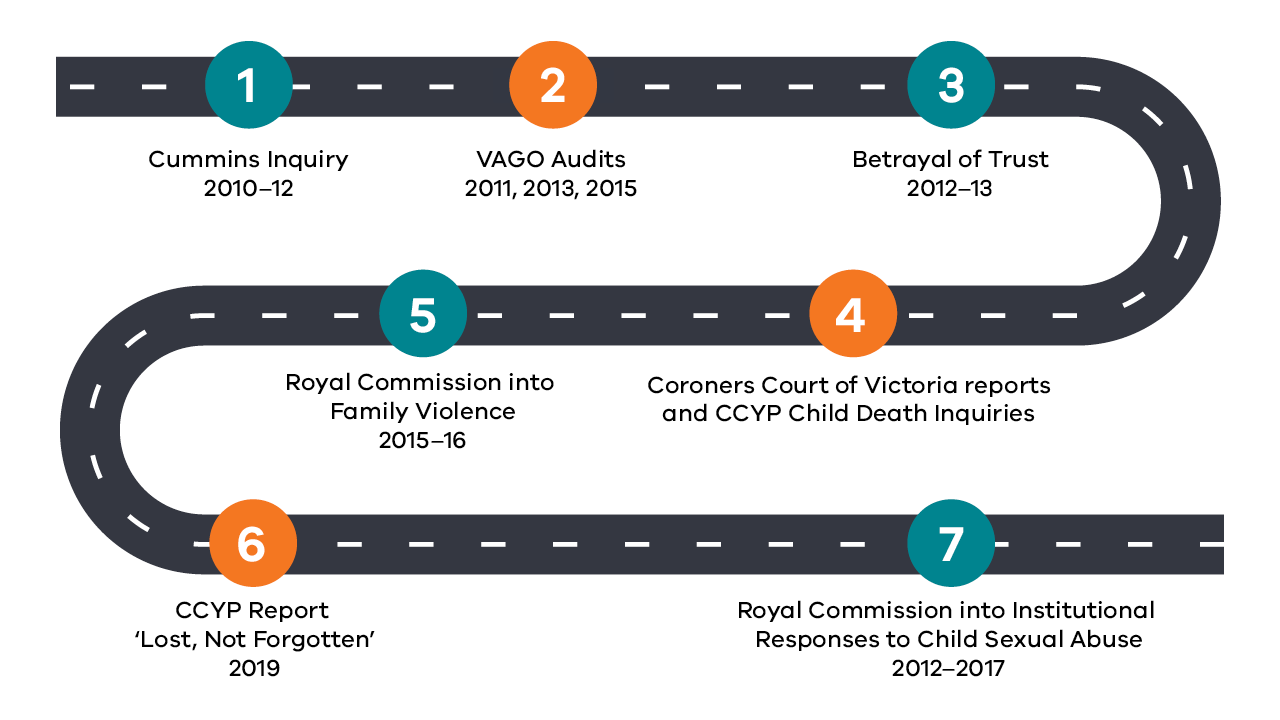

The Reforms enable Information Sharing Entities (ISEs) to request and share relevant information with one another to support child wellbeing and safety and assess or manage family violence risk. Information sharing and service collaboration are vital in identifying risks early and facilitating early and appropriately targeted support. Numerous Royal Commissions, coronial inquests and independent inquiries over a decade have made this clear.

The Reforms authorise schools and services, system and statutory bodies, and education health, wellbeing and inclusion workforces to:

- respond to requests for information to promote child wellbeing or safety, and/or assess and manage risk of family violence (this is mandatory)

- request information to promote child wellbeing or safety and/or manage risk of family violence

- proactively share information to promote child wellbeing or safety and/or manage risk of family violence.

The Reforms have been designed to promote the wellbeing and safety of children and families by:

- improving earlier identification of issues or risks, including family violence risk, and enabling earlier support and participation in services

- increasing collaboration and supporting a more coordinated and integrated approach to service delivery across the service system

- empowering professionals to make informed decisions

- promoting shared responsibility for wellbeing and safety, and defining responsibilities for identifying and responding to family violence across the service system, including creating consistent and collaborative practice

- identifying wellbeing and safety issues and risks, and obtaining relevant information to share in relation to family violence (by applying MARAM guidance on what to look for and what questions to ask).

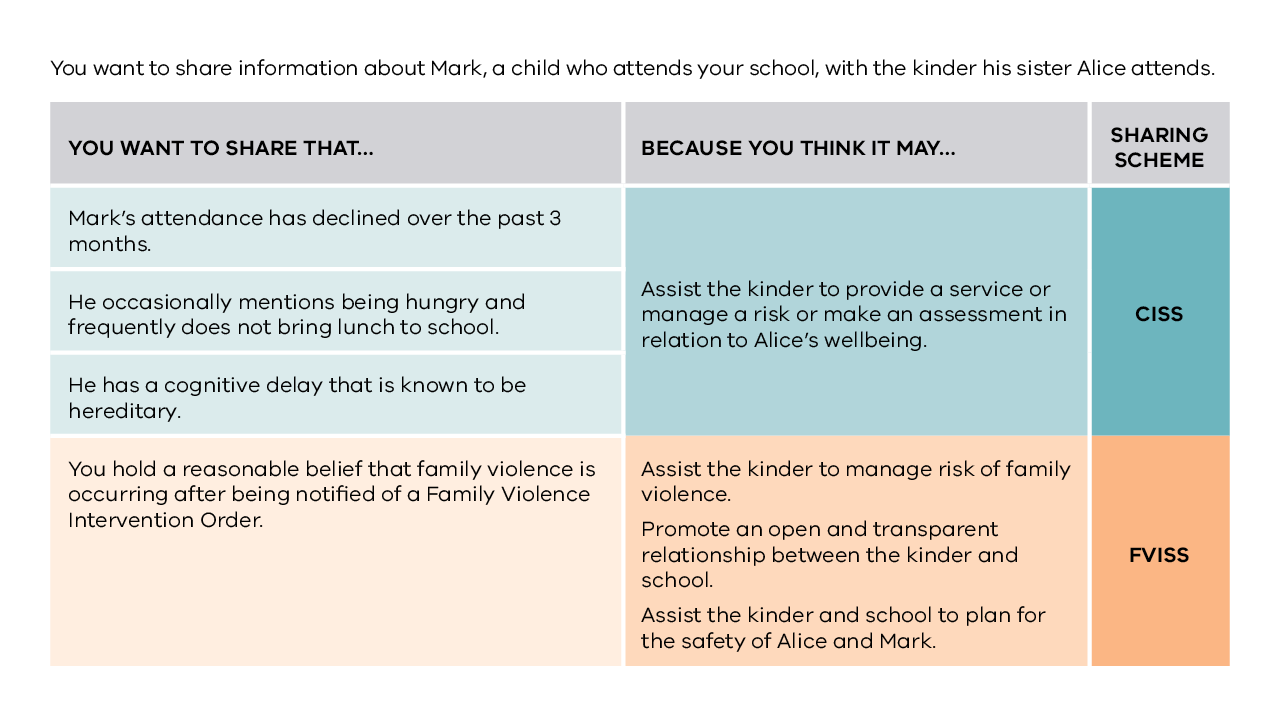

CISS enables ISEs to share relevant information about any person to promote the wellbeing or safety of a child or group of children.

Consent is not required from any person when sharing under CISS.

FVISS enables ISEs to share relevant information to assess or manage risk of family violence.

It is best practice to seek and consider the views and wishes of victim survivors when sharing their information (if safe, reasonable, and appropriate to do so). However, under FVISS consent is only required from an adult victim survivor or third party where no children are involved and there is no serious threat to an individual’s life, health, safety, or welfare.

Schools and services, system and statutory bodies, and education health, wellbeing and inclusion workforces have expanded permissions as ISEs to share information for wellbeing and safety. While the ISEs prescribed under CISS and FVISS are broadly similar, some services and organisations are prescribed under one scheme and not the other.

What is an ISE?

An ISE, or Information Sharing Entity, is an organisation or service that has been prescribed in legislation to request and share information under the Reforms.

ISEs include services that work with children, young people and families, such as:

- schools

- kindergartens

- long day care

- out of school hours care (OSHC)

- Child Protection

- youth justice

- Maternal and Child Health

- public hospitals

- Victoria Police.

For more information on the workforces prescribed as ISEs under CISS and FVISS, see Who can share information under the information sharing and MARAM reforms. You can also search for details of the organisations that are prescribed as ISEs at the ISE List.

MARAM aims to build a shared understanding of family violence across Victoria’s service system. MARAM is embedded in law and establishes the foundations for a consistent statewide approach and shared responsibility for identifying and responding to family violence.

Schools and services are prescribed as MARAM Framework organisations and are required to follow MARAM when identifying and responding to family violence. Key services such as Victoria Police, family violence specialist services, Child Protection and hospitals across Victoria are also prescribed MARAM organisations. This means that everyone in the service system has the same understanding of family violence and can respond in the same way. This ensures people get the help they need and stops them from falling through any cracks in the system.

For a list of prescribed MARAM framework organisations, see Appendix 1: Prescribed organisations.

For more information about MARAM, see Information Sharing and MARAM reforms.

Wellbeing and safety for all Victorian children

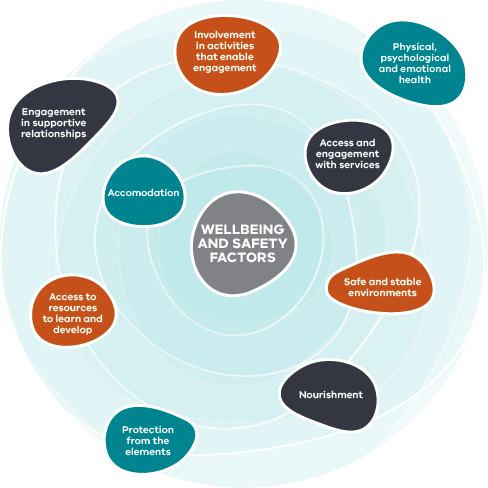

There are many factors that impact a child’s wellbeing. Parental, family, and community wellbeing, as well as cultural context and intersectional identity, all have a significant impact on a child’s wellbeing. ‘Intersectionality’ refers to the ways in which different aspects of a person’s identity can expose them to overlapping forms of discrimination and marginalisation.

When these aspects or characteristics combine:

- there is a greater risk of people experiencing family violence

- people find it harder to get the help they need due to systemic barriers

- there is increased risk of social isolation.

You should reflect on your own practice and biases to ensure you can demonstrate an understanding of how this may be experienced by Aboriginal people or people from diverse communities or at-risk age groups. Where improvements can be made, you should tailor your approach accordingly to allow access to resources and support and services to respond to family violence risk.

It is important to have a shared understanding of the protective factors for children, such as engagement in education and safe housing, as well as the factors that contribute to the wellbeing and safety of the children and families in your care. You are encouraged to use your professional judgement and build and strengthen your current practice, informed by your organisation’s existing wellbeing frameworks.

There may be instances where information needs to be shared to promote the wellbeing or safety of more than one child, including cases where one child poses a risk to another. In such cases, professionals should exercise their judgement to consider and balance each child’s wellbeing and safety to achieve the best possible outcomes for each child.

You can and should also connect with other ISEs to gather or share relevant information, and to coordinate actions to support children’s wellbeing and safety.

For more information, see Understanding child wellbeing.

Cultural safety

Aboriginal peoples and families are extremely diverse in terms of their structure and dynamics. This diversity includes the concept of family, which can be much broader than for non-Aboriginal people, encompassing kinship relationships and the broader Aboriginal community. Whatever form they take, strong families are pivotal to the health and wellbeing of Indigenous communities.

In addition to the wellbeing factors listed in Figure 2, there are a range of cultural and spiritual factors that contribute to an Aboriginal person’s wellbeing.

The wellbeing of Aboriginal peoples occurs in the context of colonisation, dispossession, and the loss of culture. This has contributed to the breakdown of kinship systems and traditional law.

To redress personal and systemic biases, all workforces engaged in risk assessment and management should participate in ongoing cultural awareness, trauma-informed practice and family violence training.

Organisations and services should promote cultural safety and recognise the cultural rights, kin and community connections of children from Aboriginal and diverse communities. They should actively value and respect a child’s identity as a core aspect of their wellbeing and safety.

The department has developed resources to help schools, services and other organisations discuss the information sharing reforms with Aboriginal families. You can view them at Child Information Sharing – caring for all Koorie children in Victoria.

Child Information Sharing Scheme Ministerial Guidance on cultural safety

When sharing information under the Child Information Sharing Scheme, legislative principles 4 and 5 require information sharing entities to:

“4. Be respectful of and have regard to a child’s social, individual, and cultural identity, the child’s strengths and abilities and any vulnerability relevant to the child’s safety or wellbeing.

5. Promote a child’s cultural safety and recognise the cultural rights and familial and community connections of children who are Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander or both.”

For the full list of legislative principles, see the Child Information Sharing Scheme Ministerial Guidelines – Introduction.

Family Violence

The Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic) defines family violence as behaviour that:

- is physically, sexually, emotionally, psychologically, or economically abusive

- is threatening or coercive

- is controlling or dominating

- causes fear for the safety or wellbeing of that family member or another person

- causes a child to hear, witness or otherwise be exposed to the effects of any behaviour referred to above.

Family violence is deeply gendered. While people of any gender can be perpetrators or victim survivors of family violence, overwhelmingly the perpetrators are men, who largely perpetrate violence against women (who are their current or former partner) and children.

Addressing family violence requires a whole-of-community response and a coordinated system working together to support adult and child victim survivors, address risk and safety needs, and promote perpetrator accountability.

“The significant majority of perpetrators are men and the significant majority of victims are women and their children.”

Working collaboratively to support wellbeing and safety

Family violence and diverse communities and at-risk groups

The Royal Commission into Family Violence found that for diverse communities and at-risk groups, family violence is less visible and understood than for other parts of the Australian community. Many also face additional barriers to reporting, as well as seeking and obtaining the help they need to be safe and recover from violence due to structural inequality and discrimination based on background, identity, and culture1.

While there can be similar dynamics to family violence across all communities, people from Aboriginal and diverse communities may also experience family violence differently. They may face barriers to reporting and finding appropriate responses and support. Barriers may result from:

- language

- visa status

- experiences of discrimination

- historic and ongoing systemic oppression

- fear of reprisals or exclusion or isolation

- concerns about their safety.

The level of risk for family violence can also change over time. For example, women are at greater risk of family violence during pregnancy or after separation from their partners.

These dynamics mean that there are additional considerations when sharing information about diverse communities and at-risk groups. Professionals are advised to seek guidance and support, including from specialist services, as needed.

For more information, see:

- Child Safe Standard 5: diversity and equity

- Child Safe Standard 1: culturally safe environments for Aboriginal children

“When services do not share information, they do not have all the necessary background to make a robust assessment that considers all the risks to a child ... when services do not meet and plan interventions, their responses can be uncoordinated and less effective.”

Commission for Children and Young People Annual report 2016–17

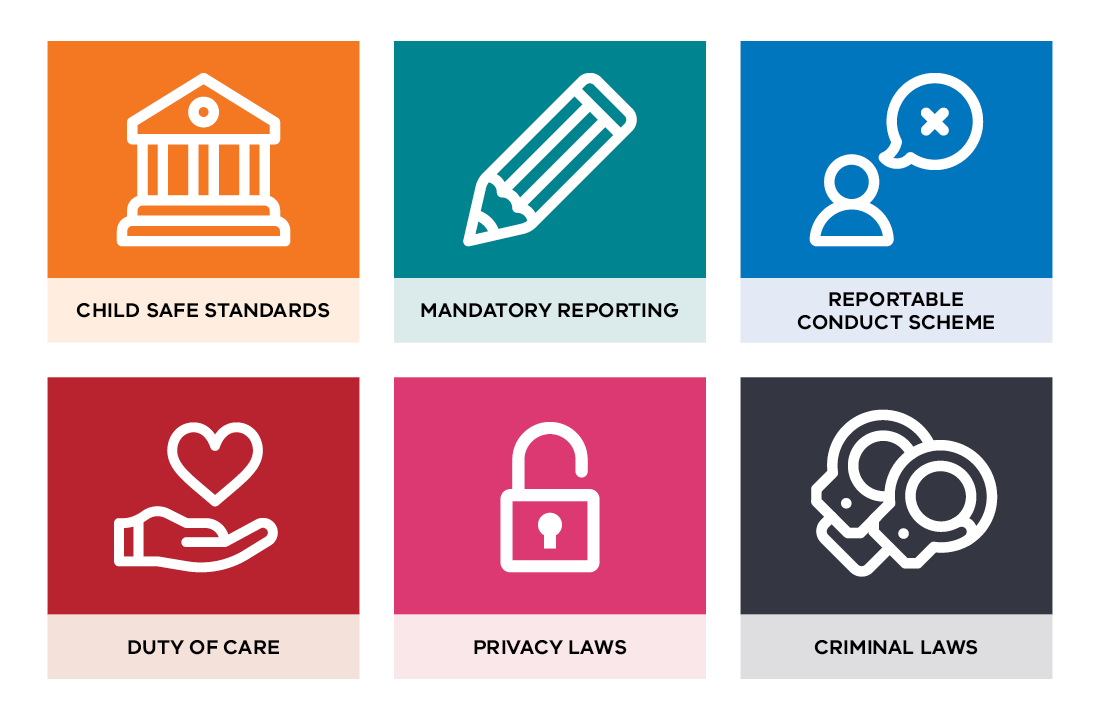

Existing child wellbeing and safety obligations

Existing child wellbeing and safety obligations continue to apply.

The Reforms expand circumstances in which confidential information (including personal, health and sensitive information) can be shared between prescribed professionals. The Reforms complement these obligations and work alongside them to support a more complete system of support for the wellbeing and safety of children.

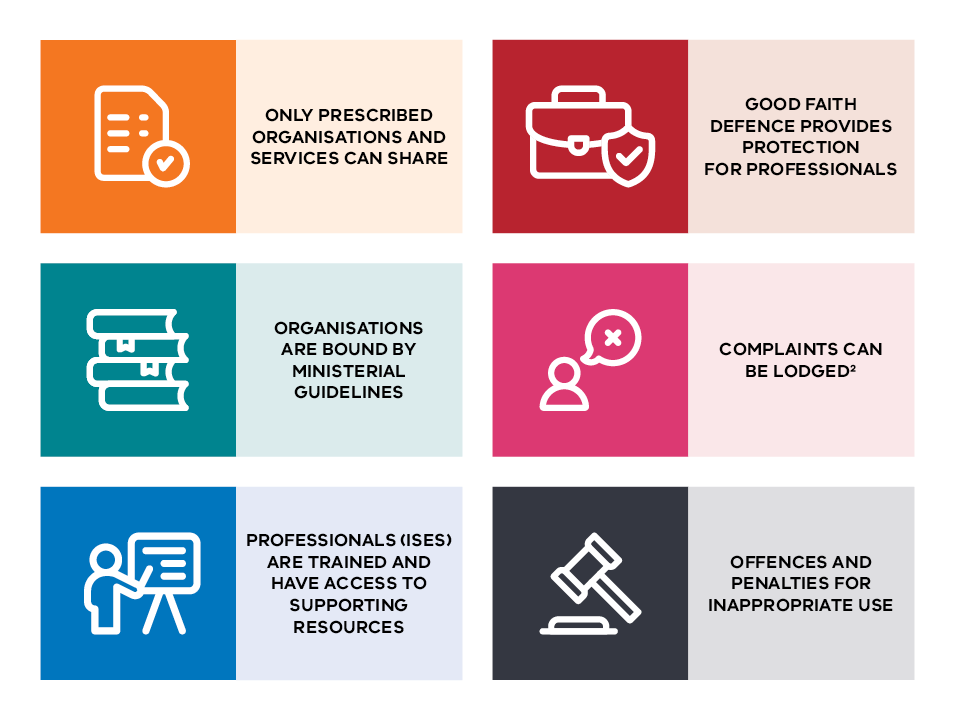

Safeguards for the Reforms

A range of safeguards and protections exist under the Reforms to ensure that professionals can safely, confidently and appropriately share information.

The good faith defence

A person who is authorised to share information under CISS and FVISS, who acts in good faith and with reasonable care when sharing information, will not be held liable for any criminal, civil or disciplinary action for providing information.

They are not considered to have breached any code of conduct or professional ethics or to have departed from any accepted standards of professional conduct.

Further reading

This resource complements training and should be read in conjunction with the Child Information Sharing Scheme Ministerial Guidelines, Family Violence Information Sharing Guidelines and MARAM Framework, as well as other resources relevant to CISS, FVISS and MARAM.

- Child Information Sharing Scheme Ministerial Guidelines

- Family Violence Information Sharing Guidelines (Go to 'Familiarise yourself with the Ministerial Guidelines')

- Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM)

- MARAM Foundation Knowledge Guide and MARAM practice guides and resources

- Information Sharing Entity list search (ISE List)

Footnotes

- Everybody Matters – Inclusion and Equity Statement – Victorian Government 2018.

- See Complaints in the Staff who Use CISS and FVISS section.

School and service leaders

Section overview

This information is relevant for me, if:

I am a school principal or a member of my school's leadership team or an early childhood service manager.

Why is this resource important to me?

This resource tells me exactly what I need to know as a leader in my organisation to ensure:

- the wellbeing and safety needs of the children and young people in my school or service are met, and

- my staff know how to identify and respond to family violence risk.

What is my responsibility?

It is my responsibility to implement information sharing and MARAM in my school or service by ensuring my staff are supported to understand and meet our organisation's legislated obligations.

What training and support do I need?

Please refer to Staff supports and other resources.

Implementing information sharing and MARAM

The department recognises that reform implementation has no one-size-fits-all approach. There is great diversity across Victorian schools and services, system and statutory bodies, and education health, wellbeing and inclusion workforces.

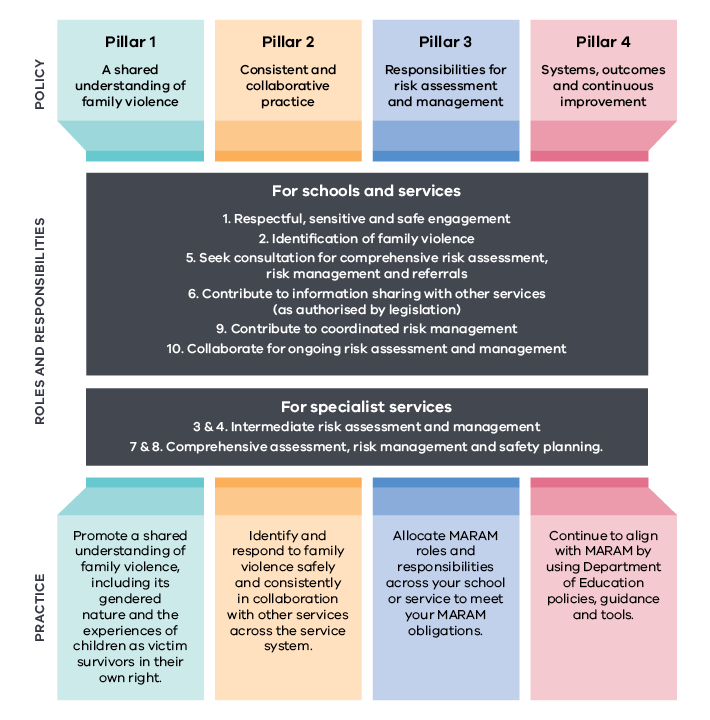

As a school or service leader, you will determine what systems and processes are best suited to your organisation to support the implementation of the Reforms. This includes identifying employees who have information sharing responsibilities, as well as MARAM nominated staff. The MARAM Framework diagram in the All staff chapter outlines the MARAM responsibilities for schools. Please see How to allocate MARAM responsibilities for more information on how to meet your school or service's MARAM legislated obligations.

Employees who have information sharing responsibilities must have skills reasonably transferable to the promotion of child and family wellbeing or safety, and the appropriate and sensitive management of confidential information. MARAM nominated staff should have qualifications, training and experience or a role aligned with wellbeing, such as wellbeing coordinators or leadership staff.

As a school or service leader, you should work closely with your existing wellbeing and safety leads or key contacts to implement the steps outlined in the Information sharing and MARAM implementation checklist to ensure your staff are able to utilise the Reforms safely and appropriately.

How to allocate MARAM responsibilities

All staff

- Responsibility 1: Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement. All staff can do this by listening to, partnering with and believing the experiences of victim survivors.

- All staff also contribute to MARAM Responsibilities 2, 5, 6, 9 and 10. All staff can do this by using the Family Violence Identification Tool to identify and respond to family violence. See All staff for more details.

MARAM nominated staff

- Responsibilities 1, 2, 5, 6, 9 and 10. MARAM nominated staff undertake screening, safety planning, information sharing and referrals. See MARAM nominated staff for more details.

Tools for school and service leaders

To access the Information sharing and MARAM checklist, refer to Tools for school and service leaders.

Tools for school and service leaders

Download the Information sharing and MARAM implementation checklist.

The Information sharing and MARAM checklist is designed to support school and service leaders to implement the information sharing and MARAM reforms, including the Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS) and Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS).

Select the link to download the checklist as an editable Word document template.

Schools and services must ensure the checklist is stored in a secure location that can only be accessed by school and service leaders, authorised staff and MARAM-nominated staff.

Accessibility statement

The Victorian Government is committed to providing a website that is accessible to the widest possible audience, regardless of technology or ability. This page may not meet our minimum WCAG AA accessibility standards.

If you are unable to read any of the content of this page, you can contact the Information Sharing and MARAM Enquiry Line for an accessible version via email at CISandFVIS@education.vic.gov.au or phone at 1800 549 646.

All staff

Section overview

This information is relevant for me, if:

I am someone who works at a school or early childhood education and care service.

Why is this resource important to me?

This resource tells me what my role and responsibilities are under the Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM).

What is my responsibility?

I am responsible for MARAM Responsibility 1: Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement. I can do this by listening to, partnering with and believing the experiences of victim survivors.

I contribute to MARAM Responsibilities 2, 5, 6, 9 and 10. I can do this by using the Family Violence Identification Tool to identify and respond to family violence.

What training and support do I need?

Please refer to Staff supports and other resources.

What is MARAM?

MARAM is a framework describing best practice for family violence risk assessment and management, based on current evidence and research. There are 10 responsibilities underpinning MARAM. The responsibilities are shared across the service system to support consistent and collaborative practice.

Under MARAM, schools and services have 6 responsibilities relating to ‘identification and screening’. These are:

- Responsibility 1: Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement

- Responsibility 2: Identification of family violence

- Responsibility 5: Seek consultation for comprehensive risk assessment, risk management and referrals

- Responsibility 6: Contribute to information sharing with other services (as authorised by legislation) (this includes FVISS and can also include CISS)

- Responsibility 9: Contribute to coordinated risk management

- Responsibility 10: Collaborate for ongoing risk assessment and risk management.

Staff in schools and services are not required to undertake:

- Responsibilities 3 and 4: Intermediate Risk Assessment and Management, and

- Responsibilities 7 and 8: Comprehensive Risk Assessment and Comprehensive Risk Management and Safety Planning.

These responsibilities are undertaken by other services, including Child Protection, family violence specialist services and Victoria Police.

How does MARAM align with PROTECT in schools and services?

Following the Four Critical Actions will help you to meet your MARAM responsibilities. The following table outlines this. If the situation is not an emergency requiring response (Critical Action 1), schools and services must still consider Critical Actions 2, 3 and 4.

Remember: Mandatory reporting obligations continue to apply to individuals who are required to report under the Children, Youth and Families Act 2005.

By itself, making a mandatory report does not acquit your school or service’s obligations under MARAM. The guidance in this resource supports staff decision-making before and after making a mandatory report.

| PROTECT Critical Action | Actions and responsibilities | MARAM responsibility |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Respond to an emergency | By responding to an emergency, you are contributing to your MARAM responsibility to create a respectful, sensitive and safe environment for people experiencing family violence. This includes prioritising the immediate health and safety of victim survivors and responding to disclosures sensitively. | 1 |

| 2. Report to authorities or refer to specialist services | By reporting to authorities and referring to the Orange Door or specialist family violence services, you are contributing to MARAM responsibilities to identify family violence, make referrals, and share information. Any staff member can use the Family Violence Identification Tool to record observable signs of trauma that may indicate family violence, evidence-based risk factors and observed narratives (e.g. statements or stories) and behaviours that may indicate an adult is using family violence. | 1, 2, 5 and 6 |

| 3. Contact parents or carers | By contacting parents or carers (if safe, reasonable and appropriate to do so) about referrals to specialist family violence services, you are contributing to MARAM responsibilities to share information and make referrals. | 1, 5 and 6 |

| 4. Provide ongoing support | By providing ongoing support, you are contributing to MARAM responsibilities for coordinated risk management and collaborating for ongoing risk assessment and management. | 1, 5, 6, 9 and 10 |

How do I identify family violence?

- Responsibility 1: Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement

- Responsibility 2: Identification of family violence

Use the Family Violence Identification Tool to record information if you:

- receive a disclosure of family violence

- observe

- signs of trauma that may indicate a child or young person is experiencing, or is at risk of experiencing, family violence

- family violence risk factors

- narratives (e.g. statements or stories) or behaviours that indicate an adult is using family violence.

You must act, by following the Four Critical Actions, as soon as you witness an incident, receive a disclosure or form a suspicion or reasonable belief that a child has, or is at risk of being abused. You do not have to directly witness the child abuse or know the source

of the abuse.

The tool is self-contained and includes instructions. The information you record in this tool will help you decide next steps.

Further information to help you identify family violence

The Family Violence Identification Tool supports you to identify family violence. This section gives you more information including more observable signs of trauma, family violence risk factors, and narratives and behaviours which may indicate an adult is using violence. If you observe or become aware of any of the following, you can record them in the Family Violence Identification Tool.

Impacts of family violence on children and young people

When responding to children experiencing family violence, it is important to remember that children are not passive witnesses or secondary victim survivors – children are victim survivors in their own right, with their own needs and experiences.

Even if violence is not directed towards the child, infants and young children can sense and understand what is occurring. A child’s exposure alone to family violence constitutes child abuse; and the longer that a child experiences or is exposed to family violence, the more harmful it is.

For more information, schools should refer to Identifying and Responding to All Forms of Abuse in Victorian Schools, see under the heading 'Guides for identifying and responding to child abuse' on Report Child Abuse in Schools. Services should see Identify Signs of Child Abuse.

A child or young person might be a victim of family violence in the following ways:

- being hit, yelled at, or otherwise directly abused

- being injured

- being sexually abused

- experiencing fear for self

- experiencing fear for another person, a pet or belongings

- seeing, hearing or otherwise sensing violence directed against another person

- seeing, hearing or otherwise sensing the aftermath of violence (such as broken furniture, smashed crockery, an atmosphere of tension)

- knowing or sensing that a family member is in fear

- being told to do something (such as to be quiet or to ‘behave’) to prevent violence

- being blamed for not preventing violence

- attempting to prevent or minimise violence

- attempting to mediate between the perpetrator and another family member

- being threatened or co-opted by the perpetrator into using violent behaviour against another family member

- being co-opted into supporting the perpetrator or taking their side

- being isolated or socially marginalised in ways that are directly attributable to the perpetrator’s controlling behaviours.

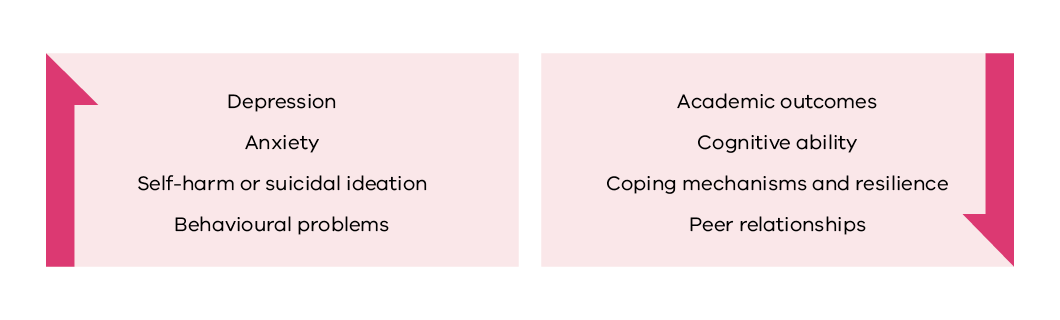

The impacts of family violence on children are profound. Trauma caused by family violence during childhood can have significant lifelong effects. There is now strong evidence that shows that early childhood attachment, safety and wellbeing provide the crucial foundation for a child’s long-term physical, social and emotional development. For example, children who experience family violence are more likely to abuse substances, be involved in crime and experience or perpetrate family violence in future relationships themselves later in life.

Observable signs of trauma in children and young people

The trauma of experiencing family violence may manifest in children and young people in different ways, depending on their age or stage of development. The following tables list behaviours you may observe in children and young people which may indicate that they are experiencing family violence, or another type of abuse or harm.

If you observe the following signs of trauma, you can record them in the Family Violence Identification Tool.

Signs of trauma for babies and toddlers

Observable signs of trauma that may indicate family violence for:

Age-related signs of trauma that may indicate family violence in a child or young person

Some indicators are related to trauma from specific forms of family violence, including sexual abuse (indicated by ~) or emotional abuse (indicated by *), or indicated by signs of neglect.

Observable signs of trauma that may indicate family violence for:

Family violence risk factors

Family violence risk factors are associated with family violence occurring and/or strongly linked to the likelihood of a perpetrator killing or seriously injuring a victim survivor.

It is important that you can recognise family violence risk factors, as they are vital for Child Protection, Victoria Police or family violence specialist services to understand and determine level of risk.

If you observe or become aware of the following family violence risk factors, you can record them in the Family Violence Identification Tool.

Risk factors specific to children’s circumstances

There is evidence that the following child circumstance factors may indicate the presence or escalation of family violence risk.

| Risk factors | Explanation |

|---|---|

| History of professional involvement and/or statutory intervention | A history of involvement of Child Protection, youth justice, mental health professionals, or other relevant professionals may indicate the presence of family violence risk, including that family violence has escalated to the level where the child requires intervention or other service support. |

| Change in behaviour not explained by other causes | A change in the behaviour of a child that cannot be explained by other causes may indicate presence of family violence or an escalation of risk of harm from family violence for the child or other family members. Children may not always verbally communicate their concerns, but may change their behaviours to respond to and manage their own risk, which may include responses such as becoming hypervigilant, aggressive, withdrawn or overly compliant. |

| Child is a victim of other forms of harm | Children’s exposure to family violence may occur within an environment of polyvictimisation. Child victims of family violence are also particularly vulnerable to further harm from opportunistic perpetrators outside the family, such as harassment, grooming and physical or sexual assault. Conversely, children who have experienced these other forms of harm are more susceptible to recurrent victimisation over their lifetimes, including family violence, and are more likely to suffer significant cumulative effects. Therefore, if a child is a victim of other forms of harm, this may indicate an elevated family violence risk. |

Risk factors specific to children caused by perpetrator behaviours

These are in addition to the risk factors for adult or child victims caused by perpetrator behaviours (see table below).

| Risk factors | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Exposure to family violence | Children are impacted, both directly and indirectly, by family violence, including the effects of family violence on the physical environment or the control of other adult or child family members. Risk of harm may be higher if the perpetrator is targeting certain children, particularly non- biological children in the family. Children’s exposure to violence may also be direct, include the perpetrator’s use of control and coercion over the child, or physical violence. The effects on children experiencing family violence include impacts on development, social and emotional wellbeing, and possible cumulative harm. |

| Sexualised behaviours towards a child by the perpetrator | There is a strong link between family violence and sexual abuse. Perpetrators who demonstrate sexualised behaviours towards a child are also more likely to use other forms of violence against them, such as:

Child sexual abuse also includes circumstances where a child may be manipulated into believing they have brought the abuse on themselves, or that the abuse is an expression of love, through a process of grooming. |

| Child intervention in violence | Children are more likely to be harmed by the perpetrator if they engage in protective behaviours for other family members or become physically or verbally involved in the violence. Additionally, where children use aggressive language and behaviour, this may indicate they are being exposed to or experiencing family violence. |

| Behaviour indicating non return of child | Perpetrator behaviours including threatening or failing to return a child can be used to harm the child and the affected parent. This risk factor includes failure to adhere to, or the undermining of, agreed childcare arrangements (or threatening to do so), threatened or actual removal of children overseas, returning children late, or not responding to contact from the affected parent when children are in the perpetrator’s care. This risk arises from or is linked to entitlement-based attitudes and a perpetrator’s sense of ownership over children. The behaviour is used as a way to control the adult victim, but also poses a serious risk to the child’s psychological, developmental and emotional wellbeing. |

| Undermining the child-parent relationship | Perpetrators often engage in behaviours that cause damage to the relationship between the adult victim survivor and their child or children. These can include tactics to undermine capacity and confidence in parenting and undermining the child–parent relationship, including manipulation of the child’s perception of the adult victim. This can have long-term impacts on the psychological, developmental and emotional wellbeing of the children, and it indicates the perpetrator’s willingness to involve children in their abuse. |

| Professional and statutory intervention | Involvement of Child Protection, counsellors, or other professionals indicates that the violence has escalated to a level where intervention is required and indicates a serious risk to a child’s psychological, developmental and emotional wellbeing. |

Risk factors relevant to an adult victim’s circumstances

| Risk factors | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Physical assault while pregnant or following birth | Family violence often commences or intensifies during pregnancy and is associated with increased rates of miscarriage, low birth weight, premature birth, foetal injury and foetal death. Family violence during pregnancy is regarded as a significant indicator of future harm to the woman and child victim. This factor is associated with control and escalation of violence already occurring. |

| Self-assessed level of risk | Victims are often good predictors of their own level of safety and risk, including as a predictor of re-assault. Professionals should be aware that some victims may communicate a feeling of safety, or minimise their level of risk, due to the perpetrator’s emotional abuse tactics creating uncertainty, denial or fear, and may still be at risk. |

| Planning to leave or recent separation | For victims who are experiencing family violence, the high-risk periods include when a victim starts planning to leave, immediately prior to taking action, and during the initial stages of or immediately after separation. Victims who stay with the perpetrator because they are afraid to leave often accurately anticipate that leaving would increase the risk of lethal assault. Victims (adult or child) are particularly at risk during the first 2 months of separation. |

| Escalation — increase in severity and/or frequency of violence | Violence occurring more often or becoming worse is associated with increased risk of lethal outcomes for victims. |

| Imminence | Certain situations can increase the risk of family violence escalating in a very short timeframe. The risk may relate to court matters, particularly family court proceedings, release from prison, relocation, or other matters outside the control of the victim which may imminently impact their level of risk. |

| Financial abuse or difficulties | Financial abuse (across socioeconomic groups), financial stress and gambling addiction, particularly of the perpetrator, are risk factors for family violence. Financial abuse is a relevant determinant of a victim survivor staying or leaving a relationship |

Risk factors for adult or child victim survivors caused by perpetrator behaviours

| Risk factors | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Controlling behaviours | Use of controlling behaviours is strongly linked to homicide. Perpetrators who feel entitled to get their way, irrespective of the views and needs of, or impact on, others are more likely to use various forms of violence against their victim, including sexual violence. Perpetrators may express ownership over family members as an articulation of control. Examples of controlling behaviours include the perpetrator telling the victim how to dress, who they can socialise with, what services they can access, limiting cultural and community connection or access to culturally appropriate services, preventing work or study, controlling their access to money or other financial abuse, and determining when they can see friends and family or use the car. Perpetrators may also use third parties to monitor and control a victim or use systems and services as a form of control over a victim, such as intervention orders and family court proceedings. |

| Access to weapons | A weapon is defined as any tool or object used by a perpetrator to threaten or intimidate, harm or kill a victim or victims, or to destroy property. Perpetrators with access to weapons, particularly guns and knives, are much more likely to seriously injure or kill a victim or victims than perpetrators without access to weapons. |

| Use of weapon in most recent event | Use of a weapon indicates a high level of risk because previous behaviour is a likely predictor of future behaviour. |

| Has ever harmed or threatened to harm victim or family members | Psychological and emotional abuse are good predictors of continued abuse, including physical abuse. Previous physical assaults also predict future assaults. Threats by the perpetrator to hurt or cause actual harm to family members, including extended family members, in Australia or overseas, can be a way of controlling the victim through fear. |

| Has ever tried to strangle or choke the victim | Strangulation or choking is a common method used by perpetrators to kill victims. It is also linked to a general increased lethality risk to a current or former partner. Loss of consciousness, including from forced restriction of airflow or blood flow to the brain, is linked to increased risk of lethality (both at the time of assault and in the following period of time) and hospitalisations, and of acquired brain injury. |

| Has ever threatened to kill victim | Evidence shows that a perpetrator’s threat to kill a victim (adult or child) is often genuine and should be taken seriously, particularly where the perpetrator has been specific or detailed, or used other forms of violence in conjunction to the threat indicating an increased risk of carrying out the threat, such as strangulation and physical violence. This includes where there are multiple victims, such as where there has been a history of family violence between intimate partners, and threats to kill or harm another family member or child or children. |

| Has ever harmed or threatened to harm or kill pets or other animals | There is a correlation between cruelty to animals and family violence, including a direct link between family violence and pets being abused or killed. Abuse or threats of abuse against pets may be used by perpetrators to control family members. |

| Has ever threatened or tried to self-harm or commit suicide | Threats or attempts to self-harm or commit suicide are a risk factor for murder–suicide. This factor is an extreme extension of controlling behaviours. |

| Stalking of victim | Stalkers are more likely to be violent if they have had an intimate relationship with the victim, including during, following separation and including when the victim has commenced a new relationship. Stalking when coupled with physical assault, is strongly connected to murder or attempted murder. Stalking behaviour and obsessive thinking are highly related behaviours. Technology-facilitated abuse, including on social media, surveillance technologies and apps is a type of stalking. |

| Sexual assault of victim | Perpetrators who sexually assault their victim (adult or child) are also more likely to use other forms of violence against them. |

| Previous or current breach of court orders or intervention orders | Breaching an intervention order, or any other order with family violence protection conditions, indicates the accused is not willing to abide by the orders of a court. It also indicates a disregard for the law and authority. Such behaviour is a serious indicator of increased risk of future violence. |

| History of family violence | Perpetrators with a history of family violence are more likely to continue to use violence against family members and in new relationships. |

| History of violent behaviour (not family violence) | Perpetrators with a history of violence are more likely to use violence against family members. This can occur even if the violence has not previously been directed towards family members. The nature of the violence may include credible threats or use of weapons and attempted or actual assaults. Perpetrators who are violent men generally engage in more frequent and more severe family violence than perpetrators who do not have a violent past. A history of criminal justice system involvement (for example, amount of time and number of occasions in and out of prison) is linked with family violence risk. |

| Obsession or jealous behaviour toward victim | A perpetrator’s obsessive and/or excessive behaviour when experiencing jealousy is often related to controlling behaviours founded in rigid beliefs about gender roles and ownership of victims and has been linked to violent attacks. |

| Unemployed or disengaged from education | A perpetrator’s unemployment is associated with an increased risk of lethal assault, and a sudden change in employment status — such as being terminated and/ or retrenched — may be associated with increased risk. Disengagement from education has similar associated risks to unemployment. |

| Drug and/or alcohol misuse or abuse | Perpetrators with a serious problem with illicit drugs, alcohol, prescription drugs or inhalants can lead to impairment in social functioning and creates an increased risk of family violence. This includes temporary drug-induced psychosis. |

| Mental illness, particularly depression | Murder–suicide outcomes in family violence have been associated with perpetrators who have mental illness, particularly depression. Mental illness may be linked with escalation, frequency and severity of violence. |

| Isolation | A victim is more vulnerable if isolated from family, friends, their community (including cultural) and the wider community and other social networks. Isolation also increases the likelihood of violence and is not simply geographic. Other examples of isolation include systemic factors that limit social interaction or facilitate the perpetrator not allowing the victim to have social interaction. |

| Physical harm | Physical harm is an act of family violence and is an indicator of increased risk of continued or escalation in severity of violence. The severity and frequency of physical harm against the victim, and the nature of the physical harm tactics, informs an understanding of the severity of risk the victim may be facing. Physical harm resulting in head trauma is linked to increased risk of lethality and hospitalisations, and of acquired brain injury. |

| Emotional abuse | Perpetrators’ use of emotional abuse can have significant impacts on the victim’s physical and mental health. Emotional abuse is used as a method to control the victim and keep them from seeking assistance. |

| Property damage | Property damage is a method of controlling the victim, through fear and intimidation. It can also contribute to financial abuse, when property damage results in a need to finance repairs. |

Narratives and behaviours which may indicate an adult is using violence

You may suspect an adult is using family violence due to the person’s account or description of experiences, themselves and their relationships (their narrative) or behaviours towards family members or professionals – these may indicate use of family violence. To help you avoid collusion, it is useful to understand the narratives and behaviours which may be demonstrated by an adult using violence.

If you observe the following narratives, you can record them in the Family Violence Identification Tool.

| Observed narratives | |

|---|---|

Beliefs or attitudes Narratives that may indicate beliefs (things that a person feels are right or correct) and attitudes (how a person expresses beliefs) that are commonly associated with likely use of family violence. |

|

Your experience engaging with the adult using violence The adult may use these narratives or behaviours with you during your engagement with them or over time. |

|

Minimising or justifying Narratives that deny, minimise or justify beliefs and attitudes, or physical and verbal behaviour. |

|

Physical and verbal behaviours Physical or verbal behaviour that may reveal the use of coercive control and violence, such as aggression, hostility or malice (in physical and/or verbal behaviour). |

|

Young people using family violence

For adolescents and young people (aged 10 to 18 years old3), the term ‘young person who uses family violence’ is used, rather than ‘perpetrator’.

It is important that this distinction be made from adults, as a more nuanced therapeutic response needs to be considered due to age, developmental stage, and that they may be victim survivors of family violence as well.

We avoid labelling these young people as ‘violent’ or as 'perpetrators', as it can lead to internalising within their identity and does not acknowledge their behaviour can be occurring within a trauma response.

Similar to adult perpetrators, family violence by young people is about patterns of power and coercive control. As with adult perpetrators, young people using violence must still be accountable for the use of violence and to learn skills and abilities to move away from the use of violence.

Violence used by young people can be towards:

- a parent, carer or siblings, other family members, including grandparents, pets:

- Family members of the child or young person often feel shame, responsibility and that they will be disbelieved or blamed. Parents often want to protect their child, avoid Child Protection or police involvement, and for those who are separated from family, see reconciliation as the ideal outcome.

- Most incidents of violence are committed by male adolescents against their mothers, but young people using violence is not as highly gendered as adult intimate partner violence.

- their own intimate partner:

- Young people can experience family violence from partners, boyfriends or girlfriends in the same way that family violence is experienced in adults. Young people may also be too fearful of further abuse, violence or reprisals, or the social impacts of seeking help to disclose or act on behaviours.

- Victim survivors may accept these behaviours or not identify them as problematic for a range of reasons:

- the behaviours are not seen as abuse or as a form of family violence

- the relationship has priority and behaviours are accepted as part of love and trust building

- the behaviours are accepted as part of gendered norms which normalise men’s dominance and control over women

- they are not aware of the legal and financial consequences of some actions.

How do I use the tool with adult victim survivors?

If children and young people hear, witness, or are exposed to the effects of family violence, they are victim survivors in their own right. The Family Violence Identification Tool supports you to identify family violence when engaging with adults in order to protect children and young people.

Observable signs of trauma

Adult victim survivors may display signs of trauma which may indicate they are experiencing family violence.

You may observe or become aware of these signs when engaging with parents or carers, such as at school pick up and drop off, parent teacher interviews or other conversations that centre around the child or young person in your care. You can record any of the signs of trauma in the table below in the Family Violence Identification Tool.

| Form | Signs that may indicate family violence is occurring for adult victims |

|---|---|

| Physical |

|

| Psychological |

|

| Emotional |

|

| Social or financial |

|

| Demeanor |

|

Working collaboratively with children, young people and adult victim survivors from diverse communities

When engaging with children, young people and adult victim survivors with diverse identities, backgrounds or circumstances, ensure that equity is upheld and diverse needs are respected in policy and practice.

This can be done through the following actions.

Recognise diverse backgrounds, needs and circumstances

Pay attention to:

- the needs of children, young people and adult victim survivors with disability or from diverse religious and cultural communities

- the impact of prior trauma from family violence or other circumstances

- gender differences in prevalence and experience of family violence

- the diverse experiences of LGBTIQA+ young people and adult victim survivors

- challenges for children and young people who are in foster care, out of home care, living away from home or international students

- young people experiencing pregnancy or young parents

- socio-economic factors (experiencing family homelessness, insecure employment or accommodation, individual or family contact with the justice system, poverty, addiction, low educational attainment, remote or regional isolation).

Identify and address challenges that people experience due to their diverse attributes

- Check in with children, young people and adult victim survivors to confirm their needs are being met. This should be in private and may occur at pick-up or drop-off, one-on-one meetings or informal discussions.

- Normalise asking for and using people’s pronouns and preferred names.

- Arrange for an interpreter if required.

Put in place policies and strategies to help meet diverse needs

- Ensure school and service environments are welcoming and inclusive by displaying flags representing different cultures within the community, providing materials in different languages and decorating with artistic expressions from children and young people.

- Conduct meetings in private and safe spaces. If meeting at the school or service, schedule the meeting so adult victim survivors do not have to navigate the grounds full of children or young people.

- Seek out expert advice to support inclusion. For example, an occupational therapist, speech pathologist, LGBTIQA+ services

or specialist services for culturally and linguistically diverse communities.

Participate in professional development and practice

- Reflect on your own privilege, preconceptions and biases when engaging with children, young people and adult victim survivors with diverse identities, backgrounds or circumstances.

- Learn about intersectionality – how individuals and communities experience multiple and overlapping forms of discrimination – and the presentations of family violence in different communities.

- Understand the systemic barriers victim survivors may face and the particular tactics perpetrators can use against them.

Aboriginal communities, family violence and cultural safety

Aboriginal people are disproportionately impacted by family violence. Evidence also shows that overwhelmingly perpetrators of family violence towards Aboriginal women are not Aboriginal people.

When working with Aboriginal children and families, it is critically important that your practice is culturally safe and responsive. To practice cultural safety means to carry out practice in collaboration with the victim survivor, with care and insight for their culture, while being mindful of your own. A culturally safe environment is one where people feel safe and where there is no challenge or need for the denial of their identity.

Cultural safety includes recognising Aboriginal community understandings of family and rights to self-determination and self-management. Culturally safe practice acknowledges Aboriginal experiences of colonisation, systemic violence and discrimination and recognises the ongoing and present-day impacts of historical events, policies, and practices.

The injustices experienced by Aboriginal people, including the dispossession of their land and traditional culture and the wrongful removal of children from their families, both historic and current, have had a profound impact on Aboriginal communities. This may impact the way children, young people, and adult victim survivors present, disclose information, and engage with services.

When working with Aboriginal people and communities, you should:

- acknowledge and respond to fears about Child Protection and the possibility of children being removed from their care when working with adult victim survivors.

- make referrals to Aboriginal community-controlled organisations that support Aboriginal lead decision making wherever possible (for nominated staff only).

- use a strengths-based approach that respects and values the collective strengths of Aboriginal knowledge, systems and expertise. Aboriginal people are the experts in their own lives.

- acknowledge that family violence against Aboriginal people can include perpetrators denying or disconnecting victim survivors from cultural identity and connection to family, community and culture.

- understand that Aboriginal family violence may relate to relationships that aren’t captured by the Western nuclear family model, for example, uncles and aunts, cousins and other community-and culturally-defined relationships.

For more information, see Child Safe Standard 5: diversity and equity guidance for early childhood services and Guidance for schools.

Engaging with someone who is suspected or known to be using violence

There may be times when you come into contact with people (such as a parent, carer or adolescent) who you suspect or know may be using family violence.

It is important that you do not ask a person you suspect of using family violence, about their use of violence, or ask questions in front of them. You should use the Family Violence Identification tool to record any narratives (e.g. statements or stories) or behaviours that may indicate an adult is using family violence.

It is the role of specialist family violence services to safely communicate with a person using violence and engage them with appropriate interventions and services.

You must act, by following the Four Critical Actions, as soon as you witness an incident, receive a disclosure or form a reasonable belief that a child has, or is at risk of being abused. You must act if you form a suspicion or reasonable belief, even if you are unsure and have not directly observed child abuse.

If you are engaging with someone who may be using violence, you should learn to identify collusion and how to avoid it, and take steps to keep yourself safe.

Avoiding collusion

The term collusion refers to ways that you might (usually unintentionally) reinforce, excuse, minimise or deny a person’s use of violence and the extent or impact of that violence. It can be expressed in a nod of agreement, a sympathetic smile or by laughing at a sexist or demeaning joke. Collusion can happen when a person’s excuses for violence are accepted without question.

You can actively avoid collusion by:

- not speaking directly with a person about their use of family violence (suspected or confirmed) – this is the role of specialist family violence services. Instead, talk to your school or service’s leadership team.

- not asking a victim survivor questions in front of a person who may be using violence - this may increase the risk for a child and their family.

How to talk about family violence

This section supports you to meet your obligations under the following MARAM responsibilities:

- Responsibility 1: Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement

- Responsibility 2: Identification of family violence

There may be times when you need to talk to a child, young person and/or adult victim survivor about family violence. For example, you might need to:

- respond immediately if a child, young person and/or adult victim survivor discloses family violence to you

- start the conversation if you suspect a child, young person and/or adult victim survivor is experiencing some wellbeing concerns or not acting like usual selves (for example, by asking prompting questions).

You should only talk to a child, young person and/or adult victim survivor if it is safe, appropriate and reasonable to do so.

Even if it is not part of your role to screen for family violence, it is important to know how to talk to children, young people and/or adult

victim survivors about family violence in a safe and supportive way. This is because a child or adult may disclose family violence to you (regardless of your role) and it is important to feel confident to respond respectfully, sensitively and safely before referring to the nominated staff at your school or service.

You do not have to be an expert in family violence. Your role is to identify if family violence might be happening and connect the family to the appropriate supports, whether that is the nominated staff or specialist services that can help assess and manage risk and support the family.

For strategies on managing disclosures, see

- Report child abuse in schools – Strategies for managing a disclosure, and

- Report child abuse in early childhood – Strategies for managing a disclosure.

Tools for all staff

To acccess the Family Violence Identification Tool, refer to Tools for all staff.

Footnotes

3. Although at 18 years, the young person is treated as an adult by the legal system.

Tools for all staff

Access the Family Violence Identification Tool.

Any school or service staff member can use the Family Violence Identification Tool to record information after receiving a disclosure of family violence, or to record observations that may indicate family violence is occurring for a child or young person.

Select the link to download the Tool as an editable Word document template.

Schools and services must ensure all copies of the Tool and the information in the Tool are stored in a secure location that can only be accessed by school and service leaders, and MARAM-nominated staff.

Accessibility statement

The Victorian Government is committed to providing a website that is accessible to the widest possible audience, regardless of technology or ability. This page may not meet our minimum WCAG AA accessibility standards.

If you are unable to read any of the content of this page, you can contact the Information Sharing and MARAM Enquiry Line for an accessible version:

- Email: CISandFVIS@education.vic.gov.au

- Phone: 1800 549 646

Staff who use CISS and FVISS

Section overview

This information is relevant for me, if:

In my role at my school or service, I use the Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS) and Family Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS), underpinned by MARAM, to support the wellbeing or safety of children and assess or manage family violence risk.

Why is this resource important to me?

This resource tells me exactly what I need to know to:

- be able to share information safely and appropriately with other prescribed services

- understand how MARAM underpins information sharing.

What is my responsibility?

I am responsible for the wellbeing and safety of the students and children in my school or service, and for developing and/or contributing to plans for students and children.

What training and support do I need?

Please refer to Staff supports and other resources.

Overview of the Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS)

The Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS) allows authorised organisations to share information to support child wellbeing or safety, to ensure that professionals can gain a complete view of the children and young people they work with, making it easier to identify wellbeing or safety needs earlier, and to act on them sooner.

The Child Information Sharing Scheme Ministerial Guidelines detail the legal obligations of prescribed Information Sharing Entities (ISEs). Additional resources are available at Information sharing and MARAM reforms.

Who?

Why?

What?

When?

How?

Principles

Excluded information under CISS

For more information, see the CISS Ministerial Guidelines.

Overview of Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS)

The Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme supports effective sharing of information to assess and manage family violence risk, through keeping perpetrators in view and accountable and promoting the safety of victim survivors of family violence.

For more comprehensive information, see the Family Violence Information Sharing Guidelines available from Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme.

Who?

Why?

What?

When?

How?

Principles

Excluded information under FVISS

For more information, see the FVISS Ministerial Guidelines, available from Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme.

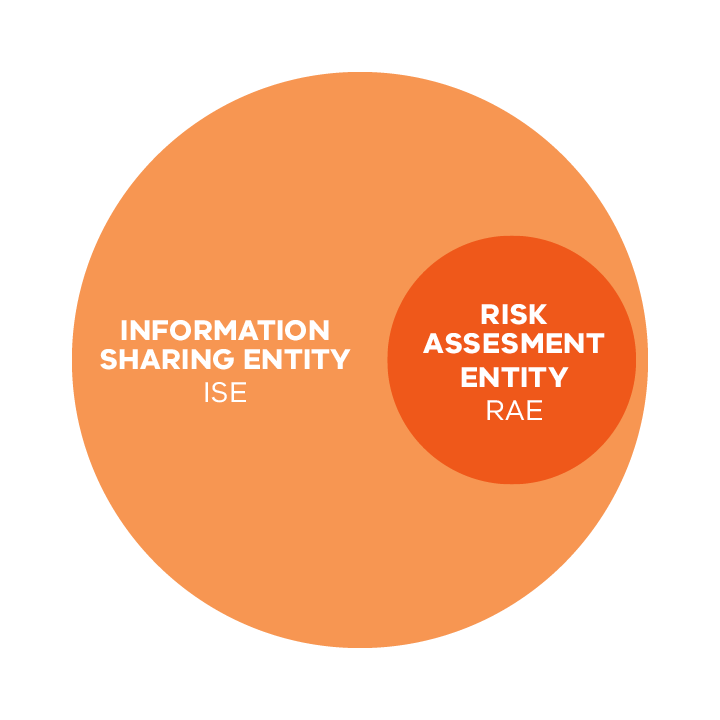

Risk Assessment Entities

Under FVISS, there is a subset of specialist ISEs known as Risk Assessment Entities (RAEs) that can request and receive information for a family violence assessment purpose. Only RAEs can request information for a family violence assessment purpose.

RAEs have specialised skills and authorisation to conduct family violence risk assessment. Examples of RAEs include:

- Victoria Police

- Child Protection

- family violence services

- the Orange Door.

Sharing for family violence risk assessment

One way in which you will be able to identify and respond to family violence is by making referrals for specialist services or professionals to complete a comprehensive family violence risk assessment. Some of these specialist services are prescribed as RAEs, such as family violence services, Child Protection and Victoria Police.

Under FVISS, ISEs such as school and service workforces can proactively share risk-relevant information with RAEs for risk assessment purposes. That is, in order to:

- confirm whether family violence is occurring

- enable RAEs to assess the level of risk the perpetrator poses to the victim survivor

- correctly identify the perpetrator of family violence and victim survivors (see section 11.3 of the MARAM Foundation Knowledge Guide for more information about misidentifying the predominant aggressor)

- respond to a request made by an RAE for information from your school or service.

Family violence risk assessment is an ongoing process, and assessment is required at different points in time from different service perspectives. Nominated staff have a role in working collaboratively with other services to contribute to ongoing risk assessment and management.

Sharing for family violence risk management

School and early childhood workforces can proactively share information with and request information from other ISEs, including RAEs,

if sharing is necessary to:

- remove, reduce or prevent family violence risk

- understand how risk is changing over time

- inform ongoing risk assessment and management through:

- secondary consultation with, or referrals to, specialist services

- developing and implementing safety plans

- managing changing risk levels over time by collaborating with other services for ongoing risk assessment and management.

Responding to external requests for MARAM and information sharing records

There are many laws in Victoria governing the security of records that you create for a child or young person at your school or service. These laws have in-built protection mechanisms that prioritise the safety of victim survivors whenever there is an application seeking the release of their information. For example, the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (Vic) has exemptions that may prevent information being released to certain alleged or confirmed perpetrators, to protect victim survivors and to ensure relevant documents are not shared with perpetrators or alleged perpetrators.

There may be a time where your school or service receives a request for information to be released externally, for example from a parent by way of Freedom of Information or subpoena during legal proceedings. These applications may include seeking access to MARAM tools and information sharing requests.

Schools and services must respond to requests for information. The department’s Requests for Information about Students Policy provides advice to government schools on how to manage requests for documents, including when to release documents directly and when to advise the person to make a FOI request to the department’s FOI Unit. This policy is consistent with Victorian privacy and information sharing law. Services and non-government schools should refer to their organisation’s policies in relation to requests for information (including FOI requests).

Consent and seeking the views and wishes of children and relevant family members

Consent under CISS

Under CISS, you can share any person’s information without their consent to promote the wellbeing or safety of a child or group of children. However, you should seek the views and wishes of the child and/or family members before sharing their information where it is safe, reasonable and appropriate to do so.

Sharing information to promote the wellbeing or safety of a student over the age of 18 would need to take place under other laws. Their consent may or may not be required depending on the privacy laws that apply.

Consent under FVISS

FVISS covers victim survivors of all ages. Consent is not required from any person to share information relevant to assessing or managing family violence risk to a child, young person and/or adult victim survivor. However, you should seek the views of the child, young person and/or adult victim survivor or a family member who is not a perpetrator where it is safe, reasonable and appropriate to do so.

Where a student over the age of 18 is experiencing family violence, and no child is at risk, consent is required from the student and any third parties to share their information unless sharing is necessary to lessen or prevent a serious threat to an individual’s life, health, safety or welfare.

In situations where an adolescent is using family violence against an adult family member, you should seek consent of the adult victim survivor and any third parties to share their information unless there is a serious threat or the information relates to assessing or managing a risk to a child.

For further information about consent, please see the Family Violence Information Sharing Guidelines and the Child Information Sharing Scheme Ministerial Guidelines.

Seeking and taking into account the views of the child and family members

Even when consent is not required, you should seek and take into account the views of the child, young person and/or any relevant family members who do not pose a risk before sharing information under CISS or FVISS if it is safe, reasonable and appropriate to do so. This is a key principle of CISS and FVISS.

There are several reasons to seek and consider the views of a child, young person or family member before sharing their information:

- working collaboratively helps develop and maintain trusting, positive relationships with the child, young person and their family, and improve and maintain service engagement

- people feel more empowered when they are included in the process and aware of and in agreement with the actions taking place

- obtaining the views of the children, including a child victim survivor, is an integral part of assessing and managing risk to the child and other family members

- children and families are often best placed to provide insight into safer, more effective ways of sharing information.

You should also inform the child or parent that their information has been shared, unless it would be unsafe, unreasonable or inappropriate to do so. Keeping them informed is best practice and helps to promote positive engagement.

The child or parent must also be supported with safety planning and other necessary services.

When seeking the views and wishes of the child, young person and their family, the discussion should explain:

- the requirements that need to be met before information can be shared

- who information can be shared with

- their consent is not required for you to share information if you believe that sharing would promote the wellbeing or safety of a child

- the benefits of information sharing, and how information may be used to promote child wellbeing or safety.

It is important to support and encourage the expression of any concerns, doubts or anxieties. You should respond sensitively, with due consideration of the circumstances children and families may be facing.

Discussing these concerns may help to inform the assessment of any risks to children’s wellbeing and safety and help to avoid unintended outcomes of information sharing. You should be aware of your own preconceptions and biases when engaging with children and families navigating barriers to wellbeing and safety.

For example, you should promote cultural safety, and demonstrate awareness of the accumulation of trauma across generations of Aboriginal communities as a result of colonisation and the dispossession of land and children.

The department has developed resources to help schools, services and other organisations discuss the child information sharing scheme with families and communities, including resources for Aboriginal families. You can view them at Child Information Sharing Scheme.

You should not seek the views and wishes of a child, young person or family member in the following circumstances:

- If it is unsafe. For example, if it is likely to jeopardise a child’s wellbeing or safety or place another person at risk of harm. Or if timeliness is an issue, such as when there is an immediate risk. Or if you are assessing or managing risk to another person

- If it is unreasonable. For example, if the child or their relevant family member does not have a service relationship with the ISE. Or if you are unable to make contact with them

- If it is inappropriate. For example, if a young person is living independently and their family members no longer have access to their personal information.

Other factors to consider when sharing information under CISS

When sharing information to promote child wellbeing and safety, you should:

- consider the child’s best interests

- promote the immediate and ongoing safety of all family members at risk of family violence in line with MARAM, noting safety includes responding to needs and circumstances that promote stabilisation and recovery from family violence

- engage specialist services as required, and promote collaborative practice around children and families

- give precedence to the wellbeing and safety of a child or group of children over the right to privacy

- preserve and promote positive relationships between a child and the child’s family members and persons of significance to the child

- be respectful of and have regard to a child’s social, individual and cultural identity, the child’s strengths and abilities and any vulnerability relevant to the child’s safety and wellbeing

- promote the cultural safety and recognise the cultural rights and familial and community connections of children who are Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander or both

- seek to maintain constructive and respectful engagement with children and their families.

Working with diverse communities and at-risk groups to support wellbeing and safety