Section overview

This information is relevant for me, if:

I am someone who works at a school or early childhood education and care service.

Why is this resource important to me?

This resource tells me what my role and responsibilities are under the Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM).

What is my responsibility?

I am responsible for MARAM Responsibility 1: Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement. I can do this by listening to, partnering with and believing the experiences of victim survivors.

I contribute to MARAM Responsibilities 2, 5, 6, 9 and 10. I can do this by using the Family Violence Identification Tool to identify and respond to family violence.

What training and support do I need?

Please refer to Staff supports and other resources.

What is MARAM?

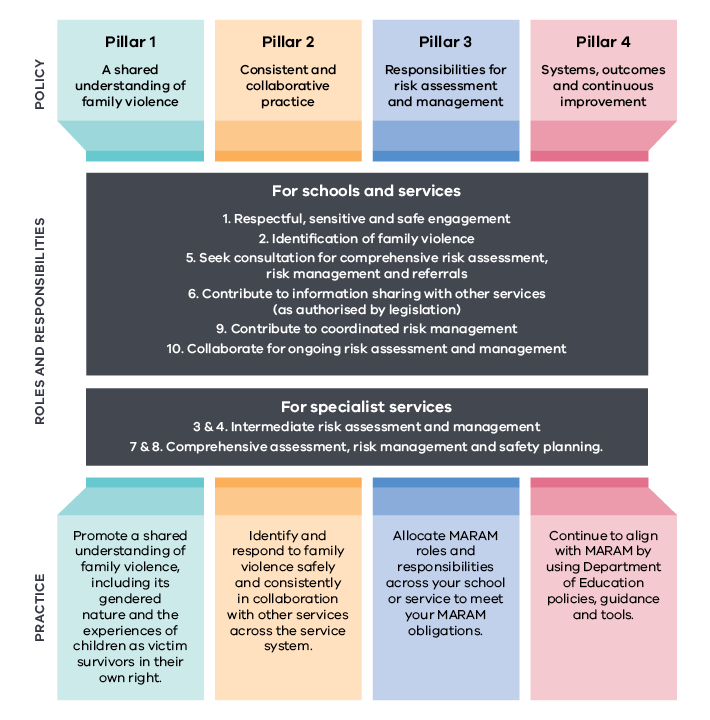

MARAM is a framework describing best practice for family violence risk assessment and management, based on current evidence and research. There are 10 responsibilities underpinning MARAM. The responsibilities are shared across the service system to support consistent and collaborative practice.

Under MARAM, schools and services have 6 responsibilities relating to ‘identification and screening’. These are:

- Responsibility 1: Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement

- Responsibility 2: Identification of family violence

- Responsibility 5: Seek consultation for comprehensive risk assessment, risk management and referrals

- Responsibility 6: Contribute to information sharing with other services (as authorised by legislation) (this includes FVISS and can also include CISS)

- Responsibility 9: Contribute to coordinated risk management

- Responsibility 10: Collaborate for ongoing risk assessment and risk management.

Staff in schools and services are not required to undertake:

- Responsibilities 3 and 4: Intermediate Risk Assessment and Management, and

- Responsibilities 7 and 8: Comprehensive Risk Assessment and Comprehensive Risk Management and Safety Planning.

These responsibilities are undertaken by other services, including Child Protection, family violence specialist services and Victoria Police.

How does MARAM align with PROTECT in schools and services?

Following the Four Critical Actions will help you to meet your MARAM responsibilities. The following table outlines this. If the situation is not an emergency requiring response (Critical Action 1), schools and services must still consider Critical Actions 2, 3 and 4.

Remember: Mandatory reporting obligations continue to apply to individuals who are required to report under the Children, Youth and Families Act 2005.

By itself, making a mandatory report does not acquit your school or service’s obligations under MARAM. The guidance in this resource supports staff decision-making before and after making a mandatory report.

| PROTECT Critical Action | Actions and responsibilities | MARAM responsibility |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Respond to an emergency | By responding to an emergency, you are contributing to your MARAM responsibility to create a respectful, sensitive and safe environment for people experiencing family violence. This includes prioritising the immediate health and safety of victim survivors and responding to disclosures sensitively. | 1 |

| 2. Report to authorities or refer to specialist services | By reporting to authorities and referring to the Orange Door or specialist family violence services, you are contributing to MARAM responsibilities to identify family violence, make referrals, and share information. Any staff member can use the Family Violence Identification Tool to record observable signs of trauma that may indicate family violence, evidence-based risk factors and observed narratives (e.g. statements or stories) and behaviours that may indicate an adult is using family violence. | 1, 2, 5 and 6 |

| 3. Contact parents or carers | By contacting parents or carers (if safe, reasonable and appropriate to do so) about referrals to specialist family violence services, you are contributing to MARAM responsibilities to share information and make referrals. | 1, 5 and 6 |

| 4. Provide ongoing support | By providing ongoing support, you are contributing to MARAM responsibilities for coordinated risk management and collaborating for ongoing risk assessment and management. | 1, 5, 6, 9 and 10 |

How do I identify family violence?

- Responsibility 1: Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement

- Responsibility 2: Identification of family violence

Use the Family Violence Identification Tool to record information if you:

- receive a disclosure of family violence

- observe

- signs of trauma that may indicate a child or young person is experiencing, or is at risk of experiencing, family violence

- family violence risk factors

- narratives (e.g. statements or stories) or behaviours that indicate an adult is using family violence.

You must act, by following the Four Critical Actions, as soon as you witness an incident, receive a disclosure or form a suspicion or reasonable belief that a child has, or is at risk of being abused. You do not have to directly witness the child abuse or know the source

of the abuse.

The tool is self-contained and includes instructions. The information you record in this tool will help you decide next steps.

Further information to help you identify family violence

The Family Violence Identification Tool supports you to identify family violence. This section gives you more information including more observable signs of trauma, family violence risk factors, and narratives and behaviours which may indicate an adult is using violence. If you observe or become aware of any of the following, you can record them in the Family Violence Identification Tool.

Impacts of family violence on children and young people

When responding to children experiencing family violence, it is important to remember that children are not passive witnesses or secondary victim survivors – children are victim survivors in their own right, with their own needs and experiences.

Even if violence is not directed towards the child, infants and young children can sense and understand what is occurring. A child’s exposure alone to family violence constitutes child abuse; and the longer that a child experiences or is exposed to family violence, the more harmful it is.

For more information, schools should refer to Identifying and Responding to All Forms of Abuse in Victorian Schools, see under the heading 'Guides for identifying and responding to child abuse' on Report Child Abuse in Schools. Services should see Identify Signs of Child Abuse.

A child or young person might be a victim of family violence in the following ways:

- being hit, yelled at, or otherwise directly abused

- being injured

- being sexually abused

- experiencing fear for self

- experiencing fear for another person, a pet or belongings

- seeing, hearing or otherwise sensing violence directed against another person

- seeing, hearing or otherwise sensing the aftermath of violence (such as broken furniture, smashed crockery, an atmosphere of tension)

- knowing or sensing that a family member is in fear

- being told to do something (such as to be quiet or to ‘behave’) to prevent violence

- being blamed for not preventing violence

- attempting to prevent or minimise violence

- attempting to mediate between the perpetrator and another family member

- being threatened or co-opted by the perpetrator into using violent behaviour against another family member

- being co-opted into supporting the perpetrator or taking their side

- being isolated or socially marginalised in ways that are directly attributable to the perpetrator’s controlling behaviours.

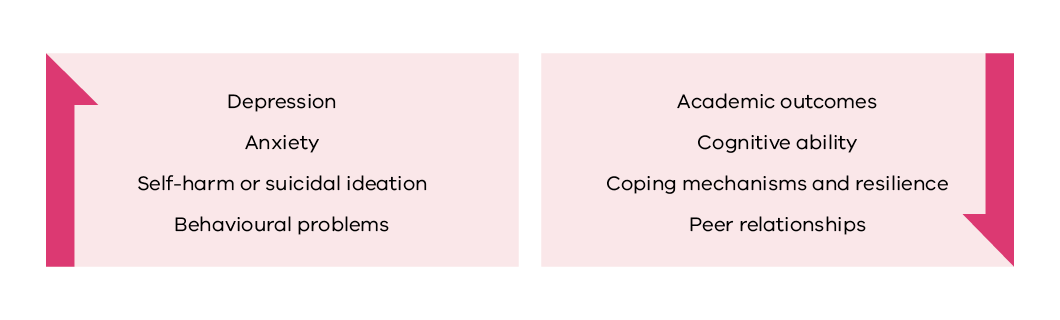

The impacts of family violence on children are profound. Trauma caused by family violence during childhood can have significant lifelong effects. There is now strong evidence that shows that early childhood attachment, safety and wellbeing provide the crucial foundation for a child’s long-term physical, social and emotional development. For example, children who experience family violence are more likely to abuse substances, be involved in crime and experience or perpetrate family violence in future relationships themselves later in life.

Observable signs of trauma in children and young people

The trauma of experiencing family violence may manifest in children and young people in different ways, depending on their age or stage of development. The following tables list behaviours you may observe in children and young people which may indicate that they are experiencing family violence, or another type of abuse or harm.

If you observe the following signs of trauma, you can record them in the Family Violence Identification Tool.

Signs of trauma for babies and toddlers

Observable signs of trauma that may indicate family violence for:

Age-related signs of trauma that may indicate family violence in a child or young person

Some indicators are related to trauma from specific forms of family violence, including sexual abuse (indicated by ~) or emotional abuse (indicated by *), or indicated by signs of neglect.

Observable signs of trauma that may indicate family violence for:

Family violence risk factors

Family violence risk factors are associated with family violence occurring and/or strongly linked to the likelihood of a perpetrator killing or seriously injuring a victim survivor.

It is important that you can recognise family violence risk factors, as they are vital for Child Protection, Victoria Police or family violence specialist services to understand and determine level of risk.

If you observe or become aware of the following family violence risk factors, you can record them in the Family Violence Identification Tool.

Risk factors specific to children’s circumstances

There is evidence that the following child circumstance factors may indicate the presence or escalation of family violence risk.

| Risk factors | Explanation |

|---|---|

| History of professional involvement and/or statutory intervention | A history of involvement of Child Protection, youth justice, mental health professionals, or other relevant professionals may indicate the presence of family violence risk, including that family violence has escalated to the level where the child requires intervention or other service support. |

| Change in behaviour not explained by other causes | A change in the behaviour of a child that cannot be explained by other causes may indicate presence of family violence or an escalation of risk of harm from family violence for the child or other family members. Children may not always verbally communicate their concerns, but may change their behaviours to respond to and manage their own risk, which may include responses such as becoming hypervigilant, aggressive, withdrawn or overly compliant. |

| Child is a victim of other forms of harm | Children’s exposure to family violence may occur within an environment of polyvictimisation. Child victims of family violence are also particularly vulnerable to further harm from opportunistic perpetrators outside the family, such as harassment, grooming and physical or sexual assault. Conversely, children who have experienced these other forms of harm are more susceptible to recurrent victimisation over their lifetimes, including family violence, and are more likely to suffer significant cumulative effects. Therefore, if a child is a victim of other forms of harm, this may indicate an elevated family violence risk. |

Risk factors specific to children caused by perpetrator behaviours

These are in addition to the risk factors for adult or child victims caused by perpetrator behaviours (see table below).

| Risk factors | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Exposure to family violence | Children are impacted, both directly and indirectly, by family violence, including the effects of family violence on the physical environment or the control of other adult or child family members. Risk of harm may be higher if the perpetrator is targeting certain children, particularly non- biological children in the family. Children’s exposure to violence may also be direct, include the perpetrator’s use of control and coercion over the child, or physical violence. The effects on children experiencing family violence include impacts on development, social and emotional wellbeing, and possible cumulative harm. |

| Sexualised behaviours towards a child by the perpetrator | There is a strong link between family violence and sexual abuse. Perpetrators who demonstrate sexualised behaviours towards a child are also more likely to use other forms of violence against them, such as:

Child sexual abuse also includes circumstances where a child may be manipulated into believing they have brought the abuse on themselves, or that the abuse is an expression of love, through a process of grooming. |

| Child intervention in violence | Children are more likely to be harmed by the perpetrator if they engage in protective behaviours for other family members or become physically or verbally involved in the violence. Additionally, where children use aggressive language and behaviour, this may indicate they are being exposed to or experiencing family violence. |

| Behaviour indicating non return of child | Perpetrator behaviours including threatening or failing to return a child can be used to harm the child and the affected parent. This risk factor includes failure to adhere to, or the undermining of, agreed childcare arrangements (or threatening to do so), threatened or actual removal of children overseas, returning children late, or not responding to contact from the affected parent when children are in the perpetrator’s care. This risk arises from or is linked to entitlement-based attitudes and a perpetrator’s sense of ownership over children. The behaviour is used as a way to control the adult victim, but also poses a serious risk to the child’s psychological, developmental and emotional wellbeing. |

| Undermining the child-parent relationship | Perpetrators often engage in behaviours that cause damage to the relationship between the adult victim survivor and their child or children. These can include tactics to undermine capacity and confidence in parenting and undermining the child–parent relationship, including manipulation of the child’s perception of the adult victim. This can have long-term impacts on the psychological, developmental and emotional wellbeing of the children, and it indicates the perpetrator’s willingness to involve children in their abuse. |

| Professional and statutory intervention | Involvement of Child Protection, counsellors, or other professionals indicates that the violence has escalated to a level where intervention is required and indicates a serious risk to a child’s psychological, developmental and emotional wellbeing. |

Risk factors relevant to an adult victim’s circumstances

| Risk factors | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Physical assault while pregnant or following birth | Family violence often commences or intensifies during pregnancy and is associated with increased rates of miscarriage, low birth weight, premature birth, foetal injury and foetal death. Family violence during pregnancy is regarded as a significant indicator of future harm to the woman and child victim. This factor is associated with control and escalation of violence already occurring. |

| Self-assessed level of risk | Victims are often good predictors of their own level of safety and risk, including as a predictor of re-assault. Professionals should be aware that some victims may communicate a feeling of safety, or minimise their level of risk, due to the perpetrator’s emotional abuse tactics creating uncertainty, denial or fear, and may still be at risk. |

| Planning to leave or recent separation | For victims who are experiencing family violence, the high-risk periods include when a victim starts planning to leave, immediately prior to taking action, and during the initial stages of or immediately after separation. Victims who stay with the perpetrator because they are afraid to leave often accurately anticipate that leaving would increase the risk of lethal assault. Victims (adult or child) are particularly at risk during the first 2 months of separation. |

| Escalation — increase in severity and/or frequency of violence | Violence occurring more often or becoming worse is associated with increased risk of lethal outcomes for victims. |

| Imminence | Certain situations can increase the risk of family violence escalating in a very short timeframe. The risk may relate to court matters, particularly family court proceedings, release from prison, relocation, or other matters outside the control of the victim which may imminently impact their level of risk. |

| Financial abuse or difficulties | Financial abuse (across socioeconomic groups), financial stress and gambling addiction, particularly of the perpetrator, are risk factors for family violence. Financial abuse is a relevant determinant of a victim survivor staying or leaving a relationship |

Risk factors for adult or child victim survivors caused by perpetrator behaviours

| Risk factors | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Controlling behaviours | Use of controlling behaviours is strongly linked to homicide. Perpetrators who feel entitled to get their way, irrespective of the views and needs of, or impact on, others are more likely to use various forms of violence against their victim, including sexual violence. Perpetrators may express ownership over family members as an articulation of control. Examples of controlling behaviours include the perpetrator telling the victim how to dress, who they can socialise with, what services they can access, limiting cultural and community connection or access to culturally appropriate services, preventing work or study, controlling their access to money or other financial abuse, and determining when they can see friends and family or use the car. Perpetrators may also use third parties to monitor and control a victim or use systems and services as a form of control over a victim, such as intervention orders and family court proceedings. |

| Access to weapons | A weapon is defined as any tool or object used by a perpetrator to threaten or intimidate, harm or kill a victim or victims, or to destroy property. Perpetrators with access to weapons, particularly guns and knives, are much more likely to seriously injure or kill a victim or victims than perpetrators without access to weapons. |

| Use of weapon in most recent event | Use of a weapon indicates a high level of risk because previous behaviour is a likely predictor of future behaviour. |

| Has ever harmed or threatened to harm victim or family members | Psychological and emotional abuse are good predictors of continued abuse, including physical abuse. Previous physical assaults also predict future assaults. Threats by the perpetrator to hurt or cause actual harm to family members, including extended family members, in Australia or overseas, can be a way of controlling the victim through fear. |

| Has ever tried to strangle or choke the victim | Strangulation or choking is a common method used by perpetrators to kill victims. It is also linked to a general increased lethality risk to a current or former partner. Loss of consciousness, including from forced restriction of airflow or blood flow to the brain, is linked to increased risk of lethality (both at the time of assault and in the following period of time) and hospitalisations, and of acquired brain injury. |

| Has ever threatened to kill victim | Evidence shows that a perpetrator’s threat to kill a victim (adult or child) is often genuine and should be taken seriously, particularly where the perpetrator has been specific or detailed, or used other forms of violence in conjunction to the threat indicating an increased risk of carrying out the threat, such as strangulation and physical violence. This includes where there are multiple victims, such as where there has been a history of family violence between intimate partners, and threats to kill or harm another family member or child or children. |

| Has ever harmed or threatened to harm or kill pets or other animals | There is a correlation between cruelty to animals and family violence, including a direct link between family violence and pets being abused or killed. Abuse or threats of abuse against pets may be used by perpetrators to control family members. |

| Has ever threatened or tried to self-harm or commit suicide | Threats or attempts to self-harm or commit suicide are a risk factor for murder–suicide. This factor is an extreme extension of controlling behaviours. |

| Stalking of victim | Stalkers are more likely to be violent if they have had an intimate relationship with the victim, including during, following separation and including when the victim has commenced a new relationship. Stalking when coupled with physical assault, is strongly connected to murder or attempted murder. Stalking behaviour and obsessive thinking are highly related behaviours. Technology-facilitated abuse, including on social media, surveillance technologies and apps is a type of stalking. |

| Sexual assault of victim | Perpetrators who sexually assault their victim (adult or child) are also more likely to use other forms of violence against them. |

| Previous or current breach of court orders or intervention orders | Breaching an intervention order, or any other order with family violence protection conditions, indicates the accused is not willing to abide by the orders of a court. It also indicates a disregard for the law and authority. Such behaviour is a serious indicator of increased risk of future violence. |

| History of family violence | Perpetrators with a history of family violence are more likely to continue to use violence against family members and in new relationships. |

| History of violent behaviour (not family violence) | Perpetrators with a history of violence are more likely to use violence against family members. This can occur even if the violence has not previously been directed towards family members. The nature of the violence may include credible threats or use of weapons and attempted or actual assaults. Perpetrators who are violent men generally engage in more frequent and more severe family violence than perpetrators who do not have a violent past. A history of criminal justice system involvement (for example, amount of time and number of occasions in and out of prison) is linked with family violence risk. |

| Obsession or jealous behaviour toward victim | A perpetrator’s obsessive and/or excessive behaviour when experiencing jealousy is often related to controlling behaviours founded in rigid beliefs about gender roles and ownership of victims and has been linked to violent attacks. |

| Unemployed or disengaged from education | A perpetrator’s unemployment is associated with an increased risk of lethal assault, and a sudden change in employment status — such as being terminated and/ or retrenched — may be associated with increased risk. Disengagement from education has similar associated risks to unemployment. |

| Drug and/or alcohol misuse or abuse | Perpetrators with a serious problem with illicit drugs, alcohol, prescription drugs or inhalants can lead to impairment in social functioning and creates an increased risk of family violence. This includes temporary drug-induced psychosis. |

| Mental illness, particularly depression | Murder–suicide outcomes in family violence have been associated with perpetrators who have mental illness, particularly depression. Mental illness may be linked with escalation, frequency and severity of violence. |

| Isolation | A victim is more vulnerable if isolated from family, friends, their community (including cultural) and the wider community and other social networks. Isolation also increases the likelihood of violence and is not simply geographic. Other examples of isolation include systemic factors that limit social interaction or facilitate the perpetrator not allowing the victim to have social interaction. |

| Physical harm | Physical harm is an act of family violence and is an indicator of increased risk of continued or escalation in severity of violence. The severity and frequency of physical harm against the victim, and the nature of the physical harm tactics, informs an understanding of the severity of risk the victim may be facing. Physical harm resulting in head trauma is linked to increased risk of lethality and hospitalisations, and of acquired brain injury. |

| Emotional abuse | Perpetrators’ use of emotional abuse can have significant impacts on the victim’s physical and mental health. Emotional abuse is used as a method to control the victim and keep them from seeking assistance. |

| Property damage | Property damage is a method of controlling the victim, through fear and intimidation. It can also contribute to financial abuse, when property damage results in a need to finance repairs. |

Narratives and behaviours which may indicate an adult is using violence

You may suspect an adult is using family violence due to the person’s account or description of experiences, themselves and their relationships (their narrative) or behaviours towards family members or professionals – these may indicate use of family violence. To help you avoid collusion, it is useful to understand the narratives and behaviours which may be demonstrated by an adult using violence.

If you observe the following narratives, you can record them in the Family Violence Identification Tool.

| Observed narratives | |

|---|---|

Beliefs or attitudes Narratives that may indicate beliefs (things that a person feels are right or correct) and attitudes (how a person expresses beliefs) that are commonly associated with likely use of family violence. |

|

Your experience engaging with the adult using violence The adult may use these narratives or behaviours with you during your engagement with them or over time. |

|

Minimising or justifying Narratives that deny, minimise or justify beliefs and attitudes, or physical and verbal behaviour. |

|

Physical and verbal behaviours Physical or verbal behaviour that may reveal the use of coercive control and violence, such as aggression, hostility or malice (in physical and/or verbal behaviour). |

|

Young people using family violence

For adolescents and young people (aged 10 to 18 years old3), the term ‘young person who uses family violence’ is used, rather than ‘perpetrator’.

It is important that this distinction be made from adults, as a more nuanced therapeutic response needs to be considered due to age, developmental stage, and that they may be victim survivors of family violence as well.

We avoid labelling these young people as ‘violent’ or as 'perpetrators', as it can lead to internalising within their identity and does not acknowledge their behaviour can be occurring within a trauma response.

Similar to adult perpetrators, family violence by young people is about patterns of power and coercive control. As with adult perpetrators, young people using violence must still be accountable for the use of violence and to learn skills and abilities to move away from the use of violence.

Violence used by young people can be towards:

- a parent, carer or siblings, other family members, including grandparents, pets:

- Family members of the child or young person often feel shame, responsibility and that they will be disbelieved or blamed. Parents often want to protect their child, avoid Child Protection or police involvement, and for those who are separated from family, see reconciliation as the ideal outcome.

- Most incidents of violence are committed by male adolescents against their mothers, but young people using violence is not as highly gendered as adult intimate partner violence.

- their own intimate partner:

- Young people can experience family violence from partners, boyfriends or girlfriends in the same way that family violence is experienced in adults. Young people may also be too fearful of further abuse, violence or reprisals, or the social impacts of seeking help to disclose or act on behaviours.

- Victim survivors may accept these behaviours or not identify them as problematic for a range of reasons:

- the behaviours are not seen as abuse or as a form of family violence

- the relationship has priority and behaviours are accepted as part of love and trust building

- the behaviours are accepted as part of gendered norms which normalise men’s dominance and control over women

- they are not aware of the legal and financial consequences of some actions.

How do I use the tool with adult victim survivors?

If children and young people hear, witness, or are exposed to the effects of family violence, they are victim survivors in their own right. The Family Violence Identification Tool supports you to identify family violence when engaging with adults in order to protect children and young people.

Observable signs of trauma

Adult victim survivors may display signs of trauma which may indicate they are experiencing family violence.

You may observe or become aware of these signs when engaging with parents or carers, such as at school pick up and drop off, parent teacher interviews or other conversations that centre around the child or young person in your care. You can record any of the signs of trauma in the table below in the Family Violence Identification Tool.

| Form | Signs that may indicate family violence is occurring for adult victims |

|---|---|

| Physical |

|

| Psychological |

|

| Emotional |

|

| Social or financial |

|

| Demeanor |

|

Working collaboratively with children, young people and adult victim survivors from diverse communities

When engaging with children, young people and adult victim survivors with diverse identities, backgrounds or circumstances, ensure that equity is upheld and diverse needs are respected in policy and practice.

This can be done through the following actions.

Recognise diverse backgrounds, needs and circumstances

Pay attention to:

- the needs of children, young people and adult victim survivors with disability or from diverse religious and cultural communities

- the impact of prior trauma from family violence or other circumstances

- gender differences in prevalence and experience of family violence

- the diverse experiences of LGBTIQA+ young people and adult victim survivors

- challenges for children and young people who are in foster care, out of home care, living away from home or international students

- young people experiencing pregnancy or young parents

- socio-economic factors (experiencing family homelessness, insecure employment or accommodation, individual or family contact with the justice system, poverty, addiction, low educational attainment, remote or regional isolation).

Identify and address challenges that people experience due to their diverse attributes

- Check in with children, young people and adult victim survivors to confirm their needs are being met. This should be in private and may occur at pick-up or drop-off, one-on-one meetings or informal discussions.

- Normalise asking for and using people’s pronouns and preferred names.

- Arrange for an interpreter if required.

Put in place policies and strategies to help meet diverse needs

- Ensure school and service environments are welcoming and inclusive by displaying flags representing different cultures within the community, providing materials in different languages and decorating with artistic expressions from children and young people.

- Conduct meetings in private and safe spaces. If meeting at the school or service, schedule the meeting so adult victim survivors do not have to navigate the grounds full of children or young people.

- Seek out expert advice to support inclusion. For example, an occupational therapist, speech pathologist, LGBTIQA+ services

or specialist services for culturally and linguistically diverse communities.

Participate in professional development and practice

- Reflect on your own privilege, preconceptions and biases when engaging with children, young people and adult victim survivors with diverse identities, backgrounds or circumstances.

- Learn about intersectionality – how individuals and communities experience multiple and overlapping forms of discrimination – and the presentations of family violence in different communities.

- Understand the systemic barriers victim survivors may face and the particular tactics perpetrators can use against them.

Aboriginal communities, family violence and cultural safety

Aboriginal people are disproportionately impacted by family violence. Evidence also shows that overwhelmingly perpetrators of family violence towards Aboriginal women are not Aboriginal people.

When working with Aboriginal children and families, it is critically important that your practice is culturally safe and responsive. To practice cultural safety means to carry out practice in collaboration with the victim survivor, with care and insight for their culture, while being mindful of your own. A culturally safe environment is one where people feel safe and where there is no challenge or need for the denial of their identity.

Cultural safety includes recognising Aboriginal community understandings of family and rights to self-determination and self-management. Culturally safe practice acknowledges Aboriginal experiences of colonisation, systemic violence and discrimination and recognises the ongoing and present-day impacts of historical events, policies, and practices.

The injustices experienced by Aboriginal people, including the dispossession of their land and traditional culture and the wrongful removal of children from their families, both historic and current, have had a profound impact on Aboriginal communities. This may impact the way children, young people, and adult victim survivors present, disclose information, and engage with services.

When working with Aboriginal people and communities, you should:

- acknowledge and respond to fears about Child Protection and the possibility of children being removed from their care when working with adult victim survivors.

- make referrals to Aboriginal community-controlled organisations that support Aboriginal lead decision making wherever possible (for nominated staff only).

- use a strengths-based approach that respects and values the collective strengths of Aboriginal knowledge, systems and expertise. Aboriginal people are the experts in their own lives.

- acknowledge that family violence against Aboriginal people can include perpetrators denying or disconnecting victim survivors from cultural identity and connection to family, community and culture.

- understand that Aboriginal family violence may relate to relationships that aren’t captured by the Western nuclear family model, for example, uncles and aunts, cousins and other community-and culturally-defined relationships.

For more information, see Child Safe Standard 5: diversity and equity guidance for early childhood services and Guidance for schools.

Engaging with someone who is suspected or known to be using violence

There may be times when you come into contact with people (such as a parent, carer or adolescent) who you suspect or know may be using family violence.

It is important that you do not ask a person you suspect of using family violence, about their use of violence, or ask questions in front of them. You should use the Family Violence Identification tool to record any narratives (e.g. statements or stories) or behaviours that may indicate an adult is using family violence.

It is the role of specialist family violence services to safely communicate with a person using violence and engage them with appropriate interventions and services.

You must act, by following the Four Critical Actions, as soon as you witness an incident, receive a disclosure or form a reasonable belief that a child has, or is at risk of being abused. You must act if you form a suspicion or reasonable belief, even if you are unsure and have not directly observed child abuse.

If you are engaging with someone who may be using violence, you should learn to identify collusion and how to avoid it, and take steps to keep yourself safe.

Avoiding collusion

The term collusion refers to ways that you might (usually unintentionally) reinforce, excuse, minimise or deny a person’s use of violence and the extent or impact of that violence. It can be expressed in a nod of agreement, a sympathetic smile or by laughing at a sexist or demeaning joke. Collusion can happen when a person’s excuses for violence are accepted without question.

You can actively avoid collusion by:

- not speaking directly with a person about their use of family violence (suspected or confirmed) – this is the role of specialist family violence services. Instead, talk to your school or service’s leadership team.

- not asking a victim survivor questions in front of a person who may be using violence - this may increase the risk for a child and their family.

How to talk about family violence

This section supports you to meet your obligations under the following MARAM responsibilities:

- Responsibility 1: Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement

- Responsibility 2: Identification of family violence

There may be times when you need to talk to a child, young person and/or adult victim survivor about family violence. For example, you might need to:

- respond immediately if a child, young person and/or adult victim survivor discloses family violence to you

- start the conversation if you suspect a child, young person and/or adult victim survivor is experiencing some wellbeing concerns or not acting like usual selves (for example, by asking prompting questions).

You should only talk to a child, young person and/or adult victim survivor if it is safe, appropriate and reasonable to do so.

Even if it is not part of your role to screen for family violence, it is important to know how to talk to children, young people and/or adult

victim survivors about family violence in a safe and supportive way. This is because a child or adult may disclose family violence to you (regardless of your role) and it is important to feel confident to respond respectfully, sensitively and safely before referring to the nominated staff at your school or service.

You do not have to be an expert in family violence. Your role is to identify if family violence might be happening and connect the family to the appropriate supports, whether that is the nominated staff or specialist services that can help assess and manage risk and support the family.

For strategies on managing disclosures, see

- Report child abuse in schools – Strategies for managing a disclosure, and

- Report child abuse in early childhood – Strategies for managing a disclosure.

Tools for all staff

To acccess the Family Violence Identification Tool, refer to Tools for all staff.

Footnotes

3. Although at 18 years, the young person is treated as an adult by the legal system.

Updated