This section contains guidance, considerations and resources to support you in the planning or set-up of MEL in place-based contexts.

The content should be of use to VPS staff who are involved in MEL in varied ways—be it designing, procuring, implementing or participating in an evaluation.

Key considerations for planning

This section outlines checklists and key resources to support MEL planning. The steps covered in this section are not exhaustive and the sequence that they are applied will also depend on where you are at in your MEL journey.

Defining the objectives and priorities for MEL

The first step in scoping MEL is articulating the overall purpose and objectives for Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning. There are often many stakeholders involved in a place-based approach and each group may have different interests when it comes to MEL. Whoever is leading the planning process needs to manage competing objectives and possible trade-offs. You may need spend longer on this step in order to explore and articulate the objectives and priorities for different stakeholder groups.

Key considerations

- Consider stakeholders that need to be consulted during the scoping process and their level of involvement: A collaborative process will ensure that the MEL objectives and priorities are tailored to the characteristics and priorities specific to the location and its community.

- Consider the learning and accountability needs of community stakeholders as well as government: Consider if and how government may need to be accountable to the community—this can be a helpful way of ensuring that government are adopting a partnership mindset with MEL.

- Consider developing a set of MEL principles: Sometimes, in addition to clarifying objectives and priorities, there may be a need to define the approach taken to MEL. Principles can help to articulate the agreed priorities and ways of working. See case study on Hands Up Mallee later in this section for an example of this.

Key resources

- Place-based Evaluation Framework and Toolkit (PDF, 1,318 KB): The toolkit, developed by Clear Horizon, includes a comprehensive planning tool template. Their Framework features a tool that explains the different aspects that need to be considered when designing your MEL approach.

- Department of Health and Human Services Evaluation Guide (PDF, 276 KB): This guide is designed to support staff planning and commissioning of evaluation and for anyone responsible for program development, implementation or evaluation.

- Rainbow Framework: Prepared by Better Evaluation, the framework outlines the key tasks needed for planning any monitoring and evaluation projects

Identifying an evaluation type

Identifying drivers for evaluation is an important step in MEL planning. Whether it be place-based or other contexts, evaluators commonly distinguish between the following evaluation types:

- formative for improving implementation and assess appropriateness of interventions in the relevant context in which they are delivered

- summative to judge merit or worth of an intervention and assess the extent to which the program contributed to the desired change

- economic assessments to assess resourcing and investment and can be undertaken during the formative or summative stages

- developmental evaluation supports adaptive learning in complex and emergent initiatives and can be particularly useful when place-based initiatives are in their infancy or are in periods of high innovation or complexity.

Each evaluation type can play an important role in the evaluation of place-based approaches. The maturity and current priorities of the place-based initiative can be helpful indicators for determining drivers and an approach to evaluation.

The resources shared on the previous page and below, each contain useful guidance on how to define and plan for evaluation. While the (former) Department of Health and Human Services and Better Evaluation resources have not been developed for place-based contexts specifically, the content can still be relevant, as long as you keep in mind key considerations outlined in this document as you go through your planning process.

Further reading

- The (former) Department of Health and Human Services Evaluation Guide (PDF, 276 KB) provides more details on the distinctions between different types of evaluation (see pp.4-5).

- Developmental evaluation provides an introduction to developmental evaluation. More resources can be found in Appendix C.

- More information on the opportunities and challenges for economic assessments in the Doing MEL section of this toolkit.

- The Place-based Evaluation Framework and Toolkit (PDF, 1,318 KB) has more detailed information about choosing evaluation types in place-based contexts.

Developing a theory of change or outcomes logic

A theory of change outlines the main elements of an initiative's plan for change and the explicit sequence of events that are expected to bring about change.

A good starting point for developing a place-based theory of change is to identify what the initiative is intending to achieve, including:

- long-term population-level results, or

- changes for individuals, families and communities.

In the formative stages, the actions required to lead to these changes will need to determined.

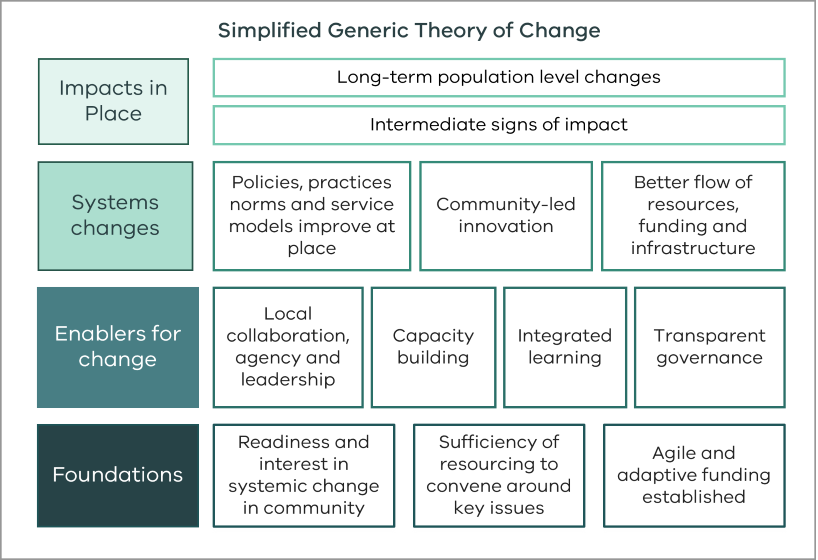

The diagram to the right, taken from the Federal Government’s Place-Based Evaluation Framework, (PDF, 1,318 KB) identifies some commonly understood components of change in place-based contexts. When developing a coherent place-based theory of change that supports effective MEL design and delivery, it is important to:

- clarify the role and relationship between each level of change and

- the connection between the adaptive ways of working and the tangible change on the ground

It may be useful to capture particular ways of working in the form of principles that sit alongside your main theory of change. Alternatively, a separate theory of change diagram may be useful to more fully articulate this aspect of the work.

Simplified Generic Theory of Change

This simplified Theory of Change is adapted from the Place based evaluation framework, national guide for evaluation of place-based approaches in Australia (PDF, 3.7 MB).

- Foundations:

- Readiness and interest in systemic change in community

- Sufficiency of resourcing to convene around key issues

- Agile and adaptive funding established

- Enablers for change:

- Local collaboration, agency and leadership

- Capacity building

- Integrated learning

- Transparent governance

- Systems changes:

- Policies, practices norms and service models improve at place

- Community-led innovation

- Better flow of resources, funding and infrastructure

- Impacts in Place:

- Long-term population level changes

- Intermediate signs of impact

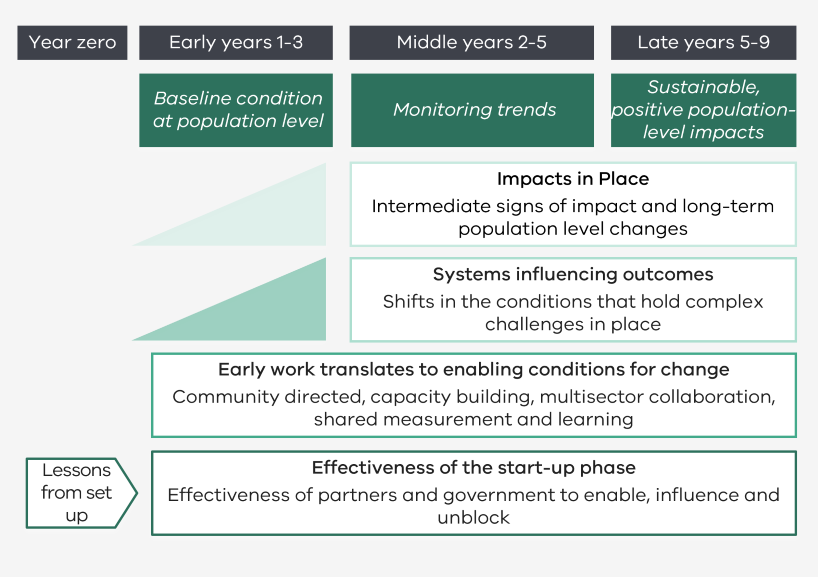

Annotated Theory of Change

This annotated version of the simplified generic Theory of Change shows how components of the theory can play out over time and possible focus areas for MEL at each time period and outcome level.

- From year zero:

- Gathering lessons from set up that can inform later work

- From early years 1-3:

- Effectiveness of the start-up phase: Effectiveness of partners and government to enable, influence and unblock

- Early work translates to enabling conditions for change: Community directed, capacity building, multisector collaboration, shared measurement and learning

- MEL activities: Baseline condition at population level

- From middle years 2-5:

- Systems influencing outcomes: Shifts in the conditions that hold complex challenges in place

- Impacts in Place: Intermediate signs of impact and long-term population level changes

- MEL activities: Monitoring trends

- Late years 5-9:

- MEL activities: Measuring sustainable, positive population-level impacts

Key considerations

- Consider the contributions of multiple stakeholders and aspects of work in your theory of change. Co-developing a theory of change will help to improve stakeholder buy-in and unite partners around a common agenda.

- Revisit your theory of change frequently. Developing a theory of change is an iterative process requiring regular updating as the context of the initiative changes.

- Consider including phases in the theory of change to capture change at different points in time. For example, have a phased theory of change to identify and track progress at appropriate time points.

- Consider developing theories of change to capture MEL outcomes of sub initiatives that comes under the broader place-based initiative.

Key resources

- Guidance on developing a theory of practice: Better Evaluation provides an overview of the different ways that you can present a theory of change.

- The Water of Systems Change: FSG in their framework outlines six conditions needed to advance systems change.

Identifying roles of government

In place-based approaches, government is often asked to show up as a genuine partner in place. This means government’s role in MEL can be significantly different compared to if they are simply funding or delivering a program or service. Through a MEL governance model, government can share power and decision-making, including by taking a more collaborative approach to setting performance expectations. Equally, MEL in place-based approaches may scrutinise the role of government in enabling or blocking systems change efforts.

Key considerations

- Explore how accountability can be meaningfully created through shared learning. Shared learning may mean moving beyond a focus on fixed, numeric reporting to government. The need for continuous learning and innovation at the community level should be a key factor in designing approaches to monitoring and learning.

- Consider accountability of all partners contributing to change. In place-based evaluations, accountability can be a two-way street meaning the role of government – how it funds, how it behaves, may be a central area for investigation in an evaluation. This differs from some traditional evaluation contexts where accountability is one way and top-down.

- Determine the level of support required from government based on the maturity and existing MEL capabilities of the initiative. The types and levels of support you provide to the initiative will be influenced by other investments and ongoing efforts made in the area and to the initiative. The way you support the initiative also depends on the capacity and flexibility of your department to accommodate the varying needs and capacities of stakeholders.

Key resources

- The Shared Power Principle (PDF, 922 KB): Developed by the Centre for Public Impact - it provides guidance to governments on power sharing with communities.

- Victorian Government Framework for place-based approaches: Identifies priorities and opportunities for government to better support place-based approaches.

Enabling collaborative engagement

Stakeholder groups involved in place-based approaches differ depending on the place and the local context. It is important that those who are affected by local challenges are active and equal participants in MEL, including in any evaluation or assessment of the outcomes of this work.

Key considerations

- Engage stakeholders that reflect the diversity of the community in an appropriate manner. Diverse communities include First Nations communities, culturally and linguistically diverse communities, people with a disability, people of different ages and LGBTIQ+ communities.

- Ensure MEL practices and data collection methods are culturally appropriate and accessible. It is important to engage with diverse communities from the outset and to ensure adjustments in approach are made so that all are able to participate in the process.

- Identify the different levels of experience and skills among stakeholders early in the process to determine their capacity to fully participate in the evaluation. You will need to consider providing tailored training so that stakeholders can meaningfully engage in the evaluation.

- Build appropriate resolution processes to manage conflict, which is inevitable when working with diverse stakeholders. For example, you could consider the benefits of developing clear principles or memorandums of understanding and ensuring there is adequate enabling infrastructure and governance mechanisms to support collaboration among partners.

Diversity and Inclusion in MEL

When working with diverse communities, it is important to find ways for these groups to have agency and genuine representation across various phases of MEL.

Key messages in the First Nations thread of this toolkit can be helpful guides when considering how to engage and work with other diverse community cohorts, including:

- centring agency and leadership in the design and implementation of MEL

- the importance of recognising and responding to cultural context.

Use a range of techniques and engagement methodologies to ensure diverse representation across a cohort of people. While peak bodies are useful organisations to represent common perspectives, they are not representative of every experience and a range of techniques and engagement is needed, particularly when tackling complex and entrenched problems.

Key resources

- Chapter Three of the Place-Based Guide: Includes guidance on engaging with diverse communities, including First Nations communities, culturally and linguistically diverse communities, people with a disability, people of different ages, and LGBTIQ+ communities.

- Appendix C: Has further resources for conducting evaluation with specific cohorts.

Resourcing

A clear understanding of the MEL needs is important in identifying resourcing levels. This includes staff skills, capabilities and time, as well as financial resources – a consideration that is particularly important in participatory and collaborative MEL processes.

Key considerations

- Dedicate time to scoping out MEL needs. Articulate MEL needs with partners, to assist in identifying if resourcing for MEL is adequate.

- Confirm the level of resourcing you have (and what you need to seek) to conduct MEL before putting together a budget. If you plan to use participatory methods, you will need to consider resourcing for building community capacity (for example in data analysis, evaluation) so that community partners can meaningfully contribute to monitoring and the evaluation. You may want to consider allocating funds for learning processes as well as for monitoring and evaluation.

- Consider factors that are particular to place that may affect resourcing including:

- size of the place-based approach and location (e.g. urban/regional)

- priorities that can influence the type of monitoring and evaluation activities and associated costs

- staff and partner capabilities to undertake parts of monitoring and evaluation or whether external expertise is needed.

Key resources

- For evaluation resourcing, see the levels of resourcing table (pp 30-32), of the National Place-Based Evaluation Framework (PDF, 3.7 MB). It provides an indication of the levels of resourcing needed based on the purpose and scope of evaluation.

Procuring MEL for a place-based approach

A clear understanding of the MEL needs is also an essential first step for procuring high-quality MEL. Identification of these needs will assist government and partners to determine external expertise required and to select proficient suppliers.

Key considerations

- Consider expertise in participatory MEL processes and methods of prospective suppliers. When assessing capability, consider if the supplier:

- outlines key practice principles for MEL

- demonstrates a good understanding of how MEL of place-based approaches differ from programmatic responses

- demonstrates knowledge on participatory and community-centric methods/approaches to MEL—for example, interviewing people with lived experience or co-producing with community stakeholders

- offers an approach for addressing the challenges of contribution/attribution and the long-term timeframes to capture impact

- demonstrates experience in facilitating learning approaches and reflective practice tools.

- Consider whether several external suppliers are required to meet various MEL needs. External evaluators may not have specialist skills in all MEL components. Consider whether you need to procure services from several external suppliers to establish and deliver specific components of MEL. Particularly, consider whether learning processes can be established and implemented by place-based partners, without the support of an external supplier. Learning is a key means to support you to test, adapt and scale up.

- Have a degree of flexibility to enable amendments to the contract and account for changes to MEL. Where possible, consider including opportunities to review the MEL approach at different points in time by building flexibility into longer-term MEL contracts.

Embedding a strategic learning culture and structures into government

When working in partnership with place-based approaches, it is important to embed learning processes into government practices to ensure ongoing improvement and increase the likelihood of achieving desired outcomes. Changes to systems, processes, mindsets and governance structures may be required in order for this work to happen effectively.

Key considerations

- Consider when adaptive and strategic learning will be most valuable. When scoping and planning MEL, it is important to begin to get a clear sense of when adaptive learning will be helpful, and the processes, capabilities and structures required to support it. This includes considering learning needs within government, across key government partners, and—importantly—with the community.

Think about useful check points to reflect on progress and opportunities to incorporate lessons into practice, strategy and policy reform. - Consider what’s required to foster a supportive learning culture. Because they are collaborative and relational, place-based approaches also require a level of readiness from government and community to work together—partners need the right mindsets, skills and resources, or be willing to build them.

In setting up MEL, government needs to appreciate that listening to and understanding the local community is a fundamental part of partnering with them. This requires intentional work to develop a culture of learning, with openness to sharing data, lessons and failures. - Identify appropriate governance structures to support strategic learning. Identifying systems and governance structures is another key planning step to ensure government supports a constructive learning agenda. Consider existing governance structures within community and government and identify possible gaps that may present barriers to ensuring learnings are captured and responded to in a timely manner. Ensuring the appropriate level of authorisation is in place in government is a critical step to support an adaptive agenda.

Key frameworks

- Building A Strategic Learning and Evaluation System for Your Organisation (FSG): The five key learning processes identified in this document are Engaging in Reflection, Engaging to Dialogue, Asking Questions, Identifying and Challenging Values, Assumptions and Beliefs, and Seeking Feedback.

- The Victorian Government Aboriginal Affairs Framework and Self-Determination Reform Framework: You can use principles in these frameworks to review if you are sharing data at the right level of decision-making, influence, control and accountability.

- Triple Loop Learning Framework (PDF, 682 KB)

This framework considers three different levels of learning. It has been adopted in innovative settings to encourage complex problem-solving and enhance performance. The framework can support groups to be clear about what it is they are aiming to learn about:- Single loop learning: About adapting to environmental changes through action

- Double loop learning: Involves questioning the framing of our actions (including strategy, values and standards, and performance)

- Triple loop learning: Focuses on interrogating the greater purpose of work (including questioning policies, values and the mission or vision)

Measurement and indicator selection

Measurement and/or indicator selection is a key part of rigorous and deliberate MEL practice as it sets the parameters for data collection. A set of agreed upon measures and indicators can help to clarify what to focus on and the sorts of data required.

Data and evidence in place-based contexts

The types of evidence used to track progress with place-based approaches does not align with the commonly accepted evidence hierarchy in government. Indigenous knowledge systems, experiential knowledge and expertise (lived experience), practice-based evidence and qualitative research are some of the types of evidence that need to be given greater weight in understanding and measuring the impacts achieved through place-based approaches. Supplementing quantitative measures with these types of data can support a rigorous and fit for purpose approach to MEL, including by identifying contribution towards outcomes, meeting cultural sensitivity consideration, and supporting in-depth learning.

Key considerations

- Consider data access and feasibility of collection through several lenses. Place-based approaches often require use of public data, service data, and primary data. When developing measures and approaches data collection, consider:

- additional resource requirements (including data platforms and systems) to support collection, storage and analysis

- legal and ethical considerations such as data ownership and sovereignty

- barriers to accessing data and the role of government in addressing these

- any arrangements required to ensure PBAs can access and use data in accordance with legislative requirements.

- Ground measures in theory of change and MEL questions. As in other contexts, developing MEL questions can be a helpful step to ensuring needs are articulated and measurement selection is adequate and is a common planning step in evaluation. Your measures should reflect the current priorities of the initiative, and should link directly to the theory of change.

- Ensure measures align with the evaluation methodology and any accompanying analytical frameworks. A measure may only signal whether a change has happened, not who or what has influenced this change, or whether it would have happened anyway. Consider which evaluation methods are required to address challenges such as contribution (for example, contribution analysis and performance rubrics).

- Don’t choose too many. Given the many possible areas for measurement, it may be better to start with a moderate set of measures to avoid being overwhelmed. You can then address gaps in measurement as they are realised. To ensure purposeful measurement selection, it can be useful to clearly articulate their relevance to specific monitoring, evaluation and learning needs of key stakeholders over time.

Example measures and indicators

To help you develop effective measures and indicators, we have created a set of example measurement areas and further guidance on developing a measure and indicator set for your place-based approach which you can find at Appendix A. The example measures and indicators are mapped against a theory of change approach over time and cover a range of elements, including enablers, systems influencing outcomes, and impacts in place. The example measures and indicators draw on the evidence of what works in practice, including from place-based approaches within Victoria, nationally and abroad.

You can use these as a starting point to inform your development of measures and indicators in place-based contexts.

Appendix A also includes an indicator bank that can be used for further guidance and inspiration during this important step.

Key resources

- Shared measurement: Though not covered in this toolkit, shared measurement is an approach that has gained popularity in Collective Impact approaches.

- SMART criteria (PDF, 145 KB): The SMART criteria offers a framework for assessing the quality of indicator selection, particularly in quantitative contexts.

- Evaluating systems change results: An Inquiry Framework (PDF, 862 KB): The framework provides guidance on the questions that can be asked when assessing systems change efforts and can help with your thinking on what constitutes a ‘result’ when developing measures.

- Place-Based Guide: This guide provides advice, case studies, tools and resources to support the use of data for MEL.

Setting up MEL from First Nations viewpoints

The relationship and connection to Country and place remains fundamental to the identity and way of life of First Nations peoples. MEL in place-based work must be done in a way that strengthens connections between people and Country, through collaborative practices, as a mechanism for shaping and sustaining the shared visions, values and experience of community members.

Culture is critical.

- This involves firstly, and most importantly, centring the worldviews, knowledge and priorities of First Nations partners within MEL and supporting First Nations communities to confidently articulate, drive and measure their own success.

- Contextual factors and cultural considerations must move beyond mere demographic descriptions of communities recognising the historical factors that created power imbalances and inequities for First Nations Communities.

- First Nations leadership and ownership should be embedded across all phases of planning and implementation of MEL.

Key phases of MEL from a First Nations lens

These key steps were developed by Black Impact and the National Centre of Indigenous Excellence:

- Yarning:

Your river fishing journey begins with a yarn about going out on the river together. Everyone is excited and has different ideas about what the journey will be like.

First engagement, reviewing tenders and having a yarn about a potential job. - Planning:

Once you've agreed to take the journey together, it's time to plan. You'll need to decide who will be part of the journey, when to go, what to bring and how the journey is going to happen.

Decision-making about accepting the tender. - Gathering:

After you've planned your journey, you begin gathering your gear and preparing for the trip. You choose a suitable boat and prepare a list of items to bring wiht you.

Writing the methodology, preparing the budget and submitting the tender. - Preparing:

Your journey is about to begin. You pack your belongings in your boat and confirm your travel plans. You brief everyone on the risks and hte signs to look out for in the environment around you (such as birds that signal bad weather of a good place to rest).

Inception planning - Leaving:

You're in the boat and beginning your journey down the river.- You have some vital tools to assist you: a mud map that a few of the mob have drawn up (theory of change) and guiding landmarks such as trees and river bends (key evaluation questions)

- You also have four other essential items for a successful trip:

- ethics

- data storage

- local experts

- data collection tools.

- Doing:

You've found a great spot on the river to stop and fish. You cast your rods and start fishing. As you catch fish (data sources) you store them in your esky.

Implementation and data collection. - Thinking:

It's now time to prepare the catch. You use your tools to remove the scales and prepare the fish for cooking.

Analysis, sense making and cleaning data. - Sharing:

The fish has been prepared and is ready to cook over an open fire. You cook the fish over hot coals to share with the group.

Reporting and sharing back data and findings. - Reflecting:

Everyone gathers together to share the meal and reflect on the journey. You think about how the fish tastes and your experiences along the river. You think about what you would do different next time and what you would do the same.

Reflecting learning.

When working with First Nations communities, it is important to:

- Recognise the importance of culture in MEL as it underpins values, processes, findings and, ultimately, outcomes. It is impossible for MEL to be meaningful to a community if the worldviews that underpin the approach to MEL are not expressly acknowledged and questioned.

- Understand what data sovereignty means to the First Nations communities you are working with and how to operationalise it.

How culture influences MEL

MEL Phase: Engaging

How Culture Influences the Work:

- How we see, experience, understand an issue/opportunity

- How we perceive a particular project

- How we view its relevance and importance to us

- Whether we feel respected, welcomed and safe to participate in it

- Whether we trust it will be done ‘the right way’ and that our voices will be heard

- How we participate in a project, what we share, with whom, how, when

What that Influences:

- Timeframe

- Relevance

- Relationship

- Respect

- Power

- Participation

MEL Phase: Framing

How Culture Influences the Work:

- How we understand/define an issue/opportunity

- What we value as being a desirable outcome, what we give primacy or priority to

- How we define “the right way” of doing things, how we make decisions

What that Influences:

- Perception

- Priorities

- Decision making

MEL Phase: Sensemaking

How Culture Influences the Work:

- What knowledge we bring and how that is conveyed

- What criteria we apply to make decisions or determine success

- What forms of evidence we pay (most) attention to

- How we explore and test ideas and perspectives

- How we manage conflicts and difference

What that Influences:

- Knowledge

- Evidence

- Analysis

- Interpretation

MEL Phase: Communicating

How Culture Influences the Work:

- How we convey and share information

- What is said, what is not said, by and to whom

What that Influences:

- Language

- Meaning

First Nations approaches to measurement

To be successful, a place-based approach should take the unique characteristics, challenges and hopes of a place and turn them into a shared vision or plan. While a vision and plan provide something tangible for cross-cultural partners to work towards, this fails to acknowledge that the vision rests within the expression and relationships people have with Country and place; and that there may be diverse experiences of Community, and thus approaches to influencing change and measuring change.

Some questions that may be considered by First Nations leaders and place-based partners when identifying measurement areas include:

- What were the things that happened that brought us together?

- Why did we decide that this was important for our Community?

- How would we describe what we are doing in our Community?

- What would we like to achieve?

Truth indicators are a valid and robust form of evidence and measurement that value and amplify the experience of First Nations peoples. Such an approach moves away from dominant culture approaches to research and evaluation, and moves to Traditional First Nations practices of oral, visual, and expressive forms of data. Utilising truth indicators is an opportunity for First Nations peoples to record evidence and share stories about our Culture, heritage, and history with the broader community.

Mayi Kuwayu - Cultural indicators

Mayi Kuwayu is a longitudinal study that surveys a large number of First Nations peoples to examine how culture is linked to health and wellbeing.

It is a First Nations controlled resource that aims to develop national level cultural indicators to inform programs and policies.

Study data may also be accessed by submitting a request to the Mayi Kuwayu Data Governance Committee for consideration.

Planning in practice: Building Foundations for First Nations Data Sovereignty: Ngiyang Wayama Data Network

What is this case study about?

A community-led data network which was established to progress data sovereignty for the local Aboriginal community in the Central Coast of NSW.

What learnings does it feature?

The case study describes Ngiyang Wayama’s practical approach to data based on a set of outcomes identified in their data strategy for the region.

Why have we included this case study?

To illustrate an example where principles for Aboriginal data sovereignty have been applied to data governance in a process involving government stakeholders.

Where can I find more information to help me apply these tools?

- Ngiyang Wayama Data Network

- OCCAAARS Framework - outlines principles of First Nations data sovereignty.

(See Appendix C for information on the above tools)

Case study

Overview

The Ngiyang Wayama (meaning ‘we all come together and talk’) Data Network works with the Central Coast Aboriginal community to increase their data literacy skills and confidence with the aim of achieving data sovereignty. The Network developed the Central Coast Regional Aboriginal Data Strategy which focuses on the outcomes below:

- Identify regional data needs through annual surveys to identify priorities across the region for different cohorts and determining a set of success measures that reflect their priorities

- Establish a regional data set by conducting a community data auditing and the development of a shared measurement framework to facilitate better data sharing across partners in the region.

- Develop data skills capacity within the region through data fluency training and in doing so, increase awareness of the value of data and gain buy in from the community.

Key considerations for Government

- Aboriginal data governance and clearly defined principles for Aboriginal data sovereignty should be established within Aboriginal place-based work as a whole, to protect and support all decisions, actions and impacts for Aboriginal peoples, including the way evaluative thinking is held in practice.

- Capacity building and learning for community members is critical and enables them to also gain insights into the workings of government.

Planning in practice: Guiding principles for MEL – Hands Up Mallee’s (HUM) MEL principles

What is this case study about?

This case study is about Hands Up Mallee (HUM), a place-based approach which works in partnership with the community, local service providers, agencies and three levels of government to improve outcomes in the community for 0-25 year olds.

This case study profiles the role and benefits of developing principles for MEL during the design phase of HUM’s MEL approach.

It has relevance for those designing MEL in complex contexts and in collaborations with divergent MEL interests.

What tools does it feature?

Outlines a collaborative approach taken to develop MEL principles.

Why did we feature this case study?

The case study has relevance for those designing MEL in complex and collaborative contexts and where there is divergence in MEL interests. By including principle development as a step in MEL planning processes, priorities can be explored and there is an explicit opportunity to collectively agree on an approach to MEL.

Case study

Overview

In 2021, HUM undertook a participatory process with collaborating partners to develop their MEL framework, which will guide learning and improvement and the building of an evidence base of HUM’s impact for the next fifteen years.

As part of this, HUM partners developed a set of shared principles and ‘lenses’ that identify their ways of working and what is important when implementing MEL.

Stakeholders participated in a facilitated co-design process that involved deep listening, iteration, and the weaving together and reconciling of diverse perspectives.

The conversation centred around the question: ‘what would good MEL look and feel like?’ for their partnership, ambitions, and context. This included considering the ‘whole’ collaboration as well as the diverse stakeholders and organisations interests and MEL needs.

HUM partners determined that they want MEL to be authentic, relevant, rigorous, and designed to fit available resources.

HUM's MEL Principles:

- Use data and evidence, both numbers and stories, for purpose/ action and to amplify our impact.

- Ensure Aboriginal communities and partners are participating and leading, and their rights for self-determination are supported.

- A culture of two-way learning for better understanding.

- Value and include the diversity of community experiences and perspectives to inform decision-making, learning, and evaluation.

- Participatory and creative approaches to build engagement, trust, and agency.

- Share data and findings in accessible, timely, and usable ways.

- Balance community and funders needs.

- Gather data and stories in ethical and respectful ways.

- A shared commitment to MEL over the long term.

Development Lenses:

The principles were then translated into a set of development lenses for their MEL framework. The six important elements of MEL identified were:

- Collaboration: Relationships, agreements, shared vision and measures

- Tracking impact: Timely, accessibility, useable and cyclic measurement, evaluation and reporting

- Community voice: Bringing community expertise, data and research together to inform planning

- Data storytelling: Being informed by data and storytelling to improve two way understanding

- Data sovereignty: Ethical and culturally appropriate gathering and use of data and stories

- Continuous and shared learning: Capacity building with internal and external expertise

Benefits for MEL:

The principles and development lenses are a testimony of HUM’s shared values and help HUM guide MEL implementation so it is inclusive and draws on multiple knowledge sources. This includes a combination of community voices, data, and research.

In the short-term: the participatory process was valuable for partnership strengthening and influenced the measures, data collection, tools, and learning of their shared MEL approach.

In the longer-term: the defined ways of working and development lenses will help HUM partners navigate the complexities of MEL implementation. They will also provide a way for the collaboration to keep accountable to, and routinely reflect on, the extent to which they are upholding their MEL principles in their social impact efforts.

Success factors:

- Adopting a participatory and iterative approach driven by listening and hands-on design by partners.

- Creating space for open conversations and investing in building MEL capacity and leadership locally through MEL coaching run in parallel to the design process.

- Working together on the MEL principles and lenses required a shift from programmatic and organisational thinking by individuals, to a ‘systems’ approach and a focus on what was important for MEL as a collaboration and for community.

Updated