- Date:

- 2 Mar 2023

About this toolkit

Welcome to this collection of practical tools and insights for working with Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL) in place-based contexts.

If you are a Victorian public servant designing, procuring, managing, supporting or participating in MEL for place-based approaches, then this toolkit is for you.

We have designed this toolkit to answer the key questions we heard from VPS employees on how you can better support effective place-based MEL from within government.

This toolkit will help you get a grounding in core concepts, navigate existing resources and discover emerging approaches. It is not intended to provide a comprehensive or step-by-step guide to implementation.

You don’t need to be an expert to use this toolkit, but if you’re new to place-based approaches or MEL we suggest you start from the beginning.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Aboriginal people as the First Peoples and Traditional Owners and custodians of the land and water on which we all rely. We acknowledge that Aboriginal communities are steeped in traditions and customs, and we respect this. We acknowledge the continuing leadership role of the Aboriginal community in striving to redress inequality and disadvantage and the catastrophic and enduring effects of colonisation.

How and when to use this toolkit

This toolkit has been designed specifically for VPS staff. Whether you are a beginner or interested in deepening your practice, this toolkit can offer you helpful examples, insights and resources.

Who this toolkit is for

This toolkit is for VPS staff who are designing, procuring, managing or participating in monitoring, evaluation and learning approaches in place-based contexts.

It was developed for use by staff with varying degrees of familiarity with place-based approaches and monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL).

How to use this toolkit

The toolkit is structured into three sections and can be used in different ways. If you are new to place-based approaches, we recommend you start from the beginning.

The introduction provides an overview of the Victorian Government’s definition of place-based approaches and what is unique about designing and implementing MEL processes for place-based approaches.

You can also skip to specific sections based on where you are at in your MEL process or the particular challenges you may be facing.

Why use this toolkit

This toolkit was developed to respond to the challenges associated with MEL processes for place-based approaches in a VPS context. It is a compilation of resources selected in response to needs and interests expressed by Victorian Government stakeholders who are involved or interested in the MEL practices associated with place-based work.

Where else can I go to learn about MEL in place-based contexts?

There are numerous resources and guidelines for conducting MEL and this toolkit should be used in tandem with the existing guidance and advice.

Several MEL resources have been specifically developed to guide place-based evaluations; the most prominent of these in Australia being the Framework and Toolkit for evaluating place-based delivery approaches.

Additionally, many departments house specialist evaluation units and have developed materials to support those involved in evaluation. The Place-Based Guide also includes valuable guidance to support the development of MEL practice in place-based settings.

Supporting resources are embedded throughout the toolkit, with a full list of resources included in Appendix C.

What’s in this toolkit

This isn’t a step-by-step guide—instead, sections are structured around the curiosities of VPS colleagues to address challenges specific to working within government and help you navigate the wealth of existing resources.

About the Introduction to MEL for place-based approaches section

What this section is:

An introduction to MEL in place-based contexts. It covers key concepts including an introduction to place-based approaches, and the value of and challenges involved in doing MEL in place-based contexts.

What this section is not:

A comprehensive overview of challenges in this space. All content is particular to the current operating environment within the VPS.

About the Setting up your approach to MEL in place-based settings section

What this section is:

A set of considerations to support VPS staff when facing key scoping and planning challenges for MEL in place-based contexts—focused on areas where VPS staff have highlighted that additional guidance will be particularly beneficial. This includes information on procuring MEL for a place-based approach.

What this section is not:

A comprehensive step-by-step planning tool. Additional resources to support MEL planning and scoping are included within the section.

About the Doing MEL in place-based settings section

What this section is:

A selection of case studies and guidance that showcase emerging approaches from Australia and internationally.

What this section is not:

While it aims to showcase key learnings, this section does not go into enough detail to inform whether approaches are appropriate for particular contexts. Where possible, we have included resources to help you understand whether approaches are applicable to your context.

About the focus on First Nations evaluation in place-based contexts

What this section is:

Throughout the document we have included lessons and guidance related to MEL in First Nations contexts. These sections provide an overview of the importance and value of supporting First Nations leadership, participation and ownership at all phases of MEL. They also offer some strategies and examples to support VPS staff to approach MEL with First Nations communities differently. The advice contained in these sections has been prepared by a First Nations MEL specialist.

What this section is not:

A comprehensive or representative one-stop-shop for conducting MEL with First Nations communities. The knowledge and approaches of local First Nations peoples, leaders and custodians of knowledge should lead all place-based works and efforts toward monitoring, evaluation and learning.

How this toolkit was developed

To make it relevant and useful, this toolkit was developed collaboratively with place-based experts and practitioners inside and outside of government.

How this toolkit was developed

The toolkit was created as part of the Whole-of-Victorian-Government Place-Based Agenda in late 2021 and 2022. The development process involved:

- Deep dive – review of literature and consultation with experts, place-based approaches from across Victoria and VPS staff from across government to understand local and international best practice, as well as the factors unique to the VPS.

- Iterative development – building the toolkit from the ground up through engaging with multiple rounds of consultation and feedback and responding to content selection and key messaging from our stakeholders to understand what is resonating and useful.

- Keeping connection to place – ensuring key learnings from MEL of place-based approaches were featured in the toolkit.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all who have contributed to the toolkit, particularly:

- The Place-Based Reform team’s Working Together in Place Learning Partners (five existing place-based initiatives in Victoria) who have generously shared their experiences and exemplary practice.

- Members of the Place-Based Evaluation Working Group, including from the Departments of Education (DoE), Families Fairness and Housing (DFFH), Health (DH), Jobs Skills Industry and Regions (DJSIR), Premier and Cabinet (DPC), and the Victorian Public Sector Commission (VPSC). The experiences, expertise and time shared to support the development of the toolkit has been invaluable.

- Clear Horizon, who have generously shared their wisdom and resources for evaluating place-based approaches, providing guidance, advice and review throughout the development of the toolkit.

- Kowa Collaboration who have contributed content and provided invaluable advice from their experience working in evaluation with First Nations people and communities, including in place-based and community-led contexts. Kowa Collaboration led the development of all First Nations sections in the toolkit.

Introduction to monitoring, evaluation and learning for place-based approaches

This section introduces you to MEL in place-based contexts. It covers key concepts including what place-based approaches are, and the value of and challenges involved in doing MEL in place-based contexts.

It dives into core ideas and challenges that you will come across in the current operating environment within the VPS, rather than providing a comprehensive overview of the space.

What do we mean by place-based approaches?

Working in place is a core part of our work—but across government we do it in different ways. From tailoring large government infrastructure projects to local need, to enabling community-owned initiatives, all these ways of working are equally valuable and can support improved community outcomes.

But when we talk about place-based approaches in this toolkit, we mean initiatives which target the specific circumstances of a place and engage the community and a broad range of local organisations from different sectors as active participants in developing and implementing solutions.

Because they are driven by local need, place-based approaches all look different. They may be initiated by community or by government; they may have started out as place-based or be evolving to a more bottom-up approach over time; they may be a stand-alone initiative or form part of a broader project or suite of measures.

But while they look different depending on their area, all place-based work requires similar capabilities from government. Crucially, place-based approaches require government to take on a partnering and enabling role and genuinely share decision-making about what outcomes matter locally and how they can best be achieved.

For more information see the Victorian Government’s Framework for Place-based Approaches.

Monitoring and Evaluation vs Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning: what is the difference and why does it matter?

Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) traditionally has had a greater focus on serving accountability and transparency purposes whereas Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL) balances these needs with those of adaptive learning.

Framing this toolkit around MEL acknowledges the critical role that data-driven learning plays in the success of place-based approaches, where an adaptive approach is critical to navigate complexity and the unknown.

Defining MEL

MEL is the systematic approach to the use and collection of data to monitor, evaluate and continuously learn and adapt an initiative throughout its implementation.

Monitoring

Monitoring refers to the routine collection, analysis and use of data, usually internally, to track how an initiative’s previously identified activities, outputs and outcomes are progressing.

Evaluation

Evaluation is the systematic process of collecting and synthesising evidence to determine the merit, worth, value or significance of an initiative to inform decision-making.

Learning

Learning refers to the translation of findings from data to improve and develop things as they are being implemented.

Why does good MEL matter?

The design and implementation of MEL can have a significant impact on the success of a place-based initiative.

- MEL can impact on the quality and integrity of the work:

- Effective MEL can steer initiatives by determining whether they are on track, whether intended outcomes are being achieved and if any changes or refinements need to be made.

- Poorly done MEL can lead to adverse outcomes, including creating unnecessary burden or undermining the community-led ethos of the work.

- MEL practices can influence future funding decisions and policy development by identifying successful work requiring additional funding or replication.

- Without MEL, there is no evidence that an initiative is making a difference to the community or of the value of government’s investments.

What’s unique about MEL in place-based contexts?

Here we drill into a few of the unique characteristics of place-based work and the implications for how we approach MEL.

Place-based approaches:

- Address long-term systemic challenges like entrenched disadvantage:

- Take an equity lens to MEL by identifying cohorts who are or are not benefitting from place-based approaches.

- Use innovative approaches to show how change is occurring in the short and long term (including systems change).

- Elevate community voice

- Government shows up as a partner in MEL to reflect the community-led nature of work.

- Reflect community priorities in all steps of design and implementation of MEL.

- Are always innovating and evolving based on local context

- Enhance focus on collecting data that can inform learning and guide development.

- Design and implement MEL in a flexible way to support innovation.

MEL within First Nations contexts

This toolkit includes a supplementary thread expressing a richer viewpoint of MEL in First Nations-led, place-based work.

The concepts and methods that are provided are from the experience and learnings of Kowa staff members.

The knowledge and approaches of local First Nations peoples, leaders and custodians of knowledge should lead all place-based works and efforts toward monitoring, impact measurement, evaluation and learning.

While the views expressed in these sections are developed with First Nations-led work in mind, they can also be applied more broadly.

The content on doing MEL within First Nations contexts is underpinned by two key ideas.

1. First Nations agency and leadership should be at the centre of MEL implementation and design

This represents a shift away from a deficit approach of ‘saving’ First Nations communities when approaching place-based work. Such an approach replaces Western evaluative practice and systems thinking with that of First Nations communities, organisations and peoples who are confidently articulating, driving and measuring their own success and using sovereign and decolonised data. Under these conditions, First Nations sovereignty and worldviews can be recognised and centred by all place-based partners.

2. Doing MEL in First Nations-led contexts requires a mindset shift

Changes to the technical approach to MEL are not enough. Rather, the role MEL plays in a place-based initiative needs reframing. Just as in the goals of place-based work, the MEL approach must also acknowledge and account for the systemic inequities faced by First Nations communities.

Key additional resources

- Victorian Government Aboriginal Affairs Framework

- The Self-Determination Reform Framework

- First Nations Cultural Safety Framework (PDF, 4.6 MB).

- A more extensive list of resources on MEL within First Nations contexts, including all resources referred to in this Toolkit is found in Appendix C.

Setting up your approach to MEL

This section contains guidance, considerations and resources to support you in the planning or set-up of MEL in place-based contexts.

The content should be of use to VPS staff who are involved in MEL in varied ways—be it designing, procuring, implementing or participating in an evaluation.

Key considerations for planning

This section outlines checklists and key resources to support MEL planning. The steps covered in this section are not exhaustive and the sequence that they are applied will also depend on where you are at in your MEL journey.

Defining the objectives and priorities for MEL

The first step in scoping MEL is articulating the overall purpose and objectives for Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning. There are often many stakeholders involved in a place-based approach and each group may have different interests when it comes to MEL. Whoever is leading the planning process needs to manage competing objectives and possible trade-offs. You may need spend longer on this step in order to explore and articulate the objectives and priorities for different stakeholder groups.

Key considerations

- Consider stakeholders that need to be consulted during the scoping process and their level of involvement: A collaborative process will ensure that the MEL objectives and priorities are tailored to the characteristics and priorities specific to the location and its community.

- Consider the learning and accountability needs of community stakeholders as well as government: Consider if and how government may need to be accountable to the community—this can be a helpful way of ensuring that government are adopting a partnership mindset with MEL.

- Consider developing a set of MEL principles: Sometimes, in addition to clarifying objectives and priorities, there may be a need to define the approach taken to MEL. Principles can help to articulate the agreed priorities and ways of working. See case study on Hands Up Mallee later in this section for an example of this.

Key resources

- Place-based Evaluation Framework and Toolkit (PDF, 1,318 KB): The toolkit, developed by Clear Horizon, includes a comprehensive planning tool template. Their Framework features a tool that explains the different aspects that need to be considered when designing your MEL approach.

- Department of Health and Human Services Evaluation Guide (PDF, 276 KB): This guide is designed to support staff planning and commissioning of evaluation and for anyone responsible for program development, implementation or evaluation.

- Rainbow Framework: Prepared by Better Evaluation, the framework outlines the key tasks needed for planning any monitoring and evaluation projects

Identifying an evaluation type

Identifying drivers for evaluation is an important step in MEL planning. Whether it be place-based or other contexts, evaluators commonly distinguish between the following evaluation types:

- formative for improving implementation and assess appropriateness of interventions in the relevant context in which they are delivered

- summative to judge merit or worth of an intervention and assess the extent to which the program contributed to the desired change

- economic assessments to assess resourcing and investment and can be undertaken during the formative or summative stages

- developmental evaluation supports adaptive learning in complex and emergent initiatives and can be particularly useful when place-based initiatives are in their infancy or are in periods of high innovation or complexity.

Each evaluation type can play an important role in the evaluation of place-based approaches. The maturity and current priorities of the place-based initiative can be helpful indicators for determining drivers and an approach to evaluation.

The resources shared on the previous page and below, each contain useful guidance on how to define and plan for evaluation. While the (former) Department of Health and Human Services and Better Evaluation resources have not been developed for place-based contexts specifically, the content can still be relevant, as long as you keep in mind key considerations outlined in this document as you go through your planning process.

Further reading

- The (former) Department of Health and Human Services Evaluation Guide (PDF, 276 KB) provides more details on the distinctions between different types of evaluation (see pp.4-5).

- Developmental evaluation provides an introduction to developmental evaluation. More resources can be found in Appendix C.

- More information on the opportunities and challenges for economic assessments in the Doing MEL section of this toolkit.

- The Place-based Evaluation Framework and Toolkit (PDF, 1,318 KB) has more detailed information about choosing evaluation types in place-based contexts.

Developing a theory of change or outcomes logic

A theory of change outlines the main elements of an initiative's plan for change and the explicit sequence of events that are expected to bring about change.

A good starting point for developing a place-based theory of change is to identify what the initiative is intending to achieve, including:

- long-term population-level results, or

- changes for individuals, families and communities.

In the formative stages, the actions required to lead to these changes will need to determined.

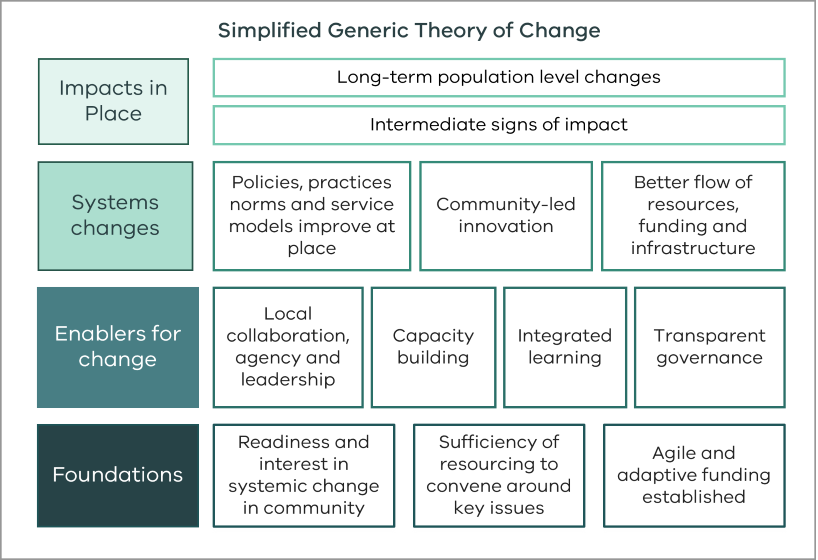

The diagram to the right, taken from the Federal Government’s Place-Based Evaluation Framework, (PDF, 1,318 KB) identifies some commonly understood components of change in place-based contexts. When developing a coherent place-based theory of change that supports effective MEL design and delivery, it is important to:

- clarify the role and relationship between each level of change and

- the connection between the adaptive ways of working and the tangible change on the ground

It may be useful to capture particular ways of working in the form of principles that sit alongside your main theory of change. Alternatively, a separate theory of change diagram may be useful to more fully articulate this aspect of the work.

Simplified Generic Theory of Change

This simplified Theory of Change is adapted from the Place based evaluation framework, national guide for evaluation of place-based approaches in Australia (PDF, 3.7 MB).

- Foundations:

- Readiness and interest in systemic change in community

- Sufficiency of resourcing to convene around key issues

- Agile and adaptive funding established

- Enablers for change:

- Local collaboration, agency and leadership

- Capacity building

- Integrated learning

- Transparent governance

- Systems changes:

- Policies, practices norms and service models improve at place

- Community-led innovation

- Better flow of resources, funding and infrastructure

- Impacts in Place:

- Long-term population level changes

- Intermediate signs of impact

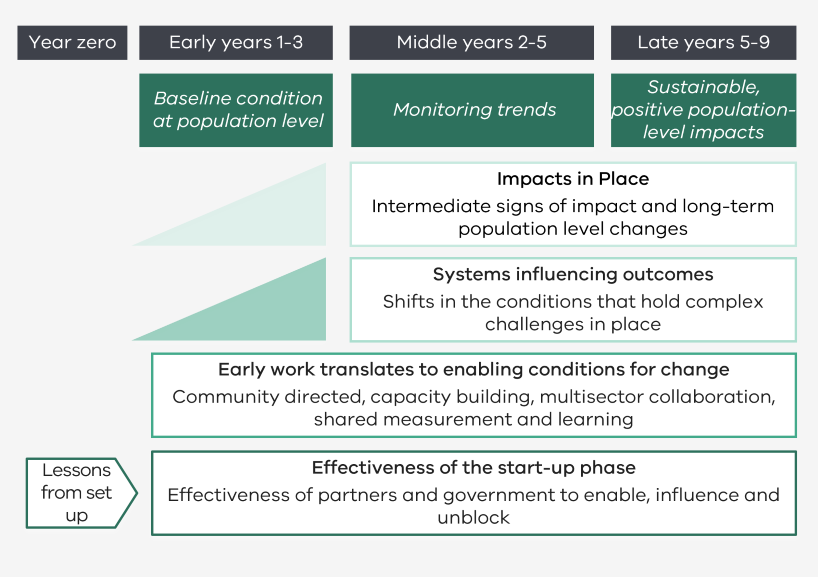

Annotated Theory of Change

This annotated version of the simplified generic Theory of Change shows how components of the theory can play out over time and possible focus areas for MEL at each time period and outcome level.

- From year zero:

- Gathering lessons from set up that can inform later work

- From early years 1-3:

- Effectiveness of the start-up phase: Effectiveness of partners and government to enable, influence and unblock

- Early work translates to enabling conditions for change: Community directed, capacity building, multisector collaboration, shared measurement and learning

- MEL activities: Baseline condition at population level

- From middle years 2-5:

- Systems influencing outcomes: Shifts in the conditions that hold complex challenges in place

- Impacts in Place: Intermediate signs of impact and long-term population level changes

- MEL activities: Monitoring trends

- Late years 5-9:

- MEL activities: Measuring sustainable, positive population-level impacts

Key considerations

- Consider the contributions of multiple stakeholders and aspects of work in your theory of change. Co-developing a theory of change will help to improve stakeholder buy-in and unite partners around a common agenda.

- Revisit your theory of change frequently. Developing a theory of change is an iterative process requiring regular updating as the context of the initiative changes.

- Consider including phases in the theory of change to capture change at different points in time. For example, have a phased theory of change to identify and track progress at appropriate time points.

- Consider developing theories of change to capture MEL outcomes of sub initiatives that comes under the broader place-based initiative.

Key resources

- Guidance on developing a theory of practice: Better Evaluation provides an overview of the different ways that you can present a theory of change.

- The Water of Systems Change: FSG in their framework outlines six conditions needed to advance systems change.

Identifying roles of government

In place-based approaches, government is often asked to show up as a genuine partner in place. This means government’s role in MEL can be significantly different compared to if they are simply funding or delivering a program or service. Through a MEL governance model, government can share power and decision-making, including by taking a more collaborative approach to setting performance expectations. Equally, MEL in place-based approaches may scrutinise the role of government in enabling or blocking systems change efforts.

Key considerations

- Explore how accountability can be meaningfully created through shared learning. Shared learning may mean moving beyond a focus on fixed, numeric reporting to government. The need for continuous learning and innovation at the community level should be a key factor in designing approaches to monitoring and learning.

- Consider accountability of all partners contributing to change. In place-based evaluations, accountability can be a two-way street meaning the role of government – how it funds, how it behaves, may be a central area for investigation in an evaluation. This differs from some traditional evaluation contexts where accountability is one way and top-down.

- Determine the level of support required from government based on the maturity and existing MEL capabilities of the initiative. The types and levels of support you provide to the initiative will be influenced by other investments and ongoing efforts made in the area and to the initiative. The way you support the initiative also depends on the capacity and flexibility of your department to accommodate the varying needs and capacities of stakeholders.

Key resources

- The Shared Power Principle (PDF, 922 KB): Developed by the Centre for Public Impact - it provides guidance to governments on power sharing with communities.

- Victorian Government Framework for place-based approaches: Identifies priorities and opportunities for government to better support place-based approaches.

Enabling collaborative engagement

Stakeholder groups involved in place-based approaches differ depending on the place and the local context. It is important that those who are affected by local challenges are active and equal participants in MEL, including in any evaluation or assessment of the outcomes of this work.

Key considerations

- Engage stakeholders that reflect the diversity of the community in an appropriate manner. Diverse communities include First Nations communities, culturally and linguistically diverse communities, people with a disability, people of different ages and LGBTIQ+ communities.

- Ensure MEL practices and data collection methods are culturally appropriate and accessible. It is important to engage with diverse communities from the outset and to ensure adjustments in approach are made so that all are able to participate in the process.

- Identify the different levels of experience and skills among stakeholders early in the process to determine their capacity to fully participate in the evaluation. You will need to consider providing tailored training so that stakeholders can meaningfully engage in the evaluation.

- Build appropriate resolution processes to manage conflict, which is inevitable when working with diverse stakeholders. For example, you could consider the benefits of developing clear principles or memorandums of understanding and ensuring there is adequate enabling infrastructure and governance mechanisms to support collaboration among partners.

Diversity and Inclusion in MEL

When working with diverse communities, it is important to find ways for these groups to have agency and genuine representation across various phases of MEL.

Key messages in the First Nations thread of this toolkit can be helpful guides when considering how to engage and work with other diverse community cohorts, including:

- centring agency and leadership in the design and implementation of MEL

- the importance of recognising and responding to cultural context.

Use a range of techniques and engagement methodologies to ensure diverse representation across a cohort of people. While peak bodies are useful organisations to represent common perspectives, they are not representative of every experience and a range of techniques and engagement is needed, particularly when tackling complex and entrenched problems.

Key resources

- Chapter Three of the Place-Based Guide: Includes guidance on engaging with diverse communities, including First Nations communities, culturally and linguistically diverse communities, people with a disability, people of different ages, and LGBTIQ+ communities.

- Appendix C: Has further resources for conducting evaluation with specific cohorts.

Resourcing

A clear understanding of the MEL needs is important in identifying resourcing levels. This includes staff skills, capabilities and time, as well as financial resources – a consideration that is particularly important in participatory and collaborative MEL processes.

Key considerations

- Dedicate time to scoping out MEL needs. Articulate MEL needs with partners, to assist in identifying if resourcing for MEL is adequate.

- Confirm the level of resourcing you have (and what you need to seek) to conduct MEL before putting together a budget. If you plan to use participatory methods, you will need to consider resourcing for building community capacity (for example in data analysis, evaluation) so that community partners can meaningfully contribute to monitoring and the evaluation. You may want to consider allocating funds for learning processes as well as for monitoring and evaluation.

- Consider factors that are particular to place that may affect resourcing including:

- size of the place-based approach and location (e.g. urban/regional)

- priorities that can influence the type of monitoring and evaluation activities and associated costs

- staff and partner capabilities to undertake parts of monitoring and evaluation or whether external expertise is needed.

Key resources

- For evaluation resourcing, see the levels of resourcing table (pp 30-32), of the National Place-Based Evaluation Framework (PDF, 3.7 MB). It provides an indication of the levels of resourcing needed based on the purpose and scope of evaluation.

Procuring MEL for a place-based approach

A clear understanding of the MEL needs is also an essential first step for procuring high-quality MEL. Identification of these needs will assist government and partners to determine external expertise required and to select proficient suppliers.

Key considerations

- Consider expertise in participatory MEL processes and methods of prospective suppliers. When assessing capability, consider if the supplier:

- outlines key practice principles for MEL

- demonstrates a good understanding of how MEL of place-based approaches differ from programmatic responses

- demonstrates knowledge on participatory and community-centric methods/approaches to MEL—for example, interviewing people with lived experience or co-producing with community stakeholders

- offers an approach for addressing the challenges of contribution/attribution and the long-term timeframes to capture impact

- demonstrates experience in facilitating learning approaches and reflective practice tools.

- Consider whether several external suppliers are required to meet various MEL needs. External evaluators may not have specialist skills in all MEL components. Consider whether you need to procure services from several external suppliers to establish and deliver specific components of MEL. Particularly, consider whether learning processes can be established and implemented by place-based partners, without the support of an external supplier. Learning is a key means to support you to test, adapt and scale up.

- Have a degree of flexibility to enable amendments to the contract and account for changes to MEL. Where possible, consider including opportunities to review the MEL approach at different points in time by building flexibility into longer-term MEL contracts.

Embedding a strategic learning culture and structures into government

When working in partnership with place-based approaches, it is important to embed learning processes into government practices to ensure ongoing improvement and increase the likelihood of achieving desired outcomes. Changes to systems, processes, mindsets and governance structures may be required in order for this work to happen effectively.

Key considerations

- Consider when adaptive and strategic learning will be most valuable. When scoping and planning MEL, it is important to begin to get a clear sense of when adaptive learning will be helpful, and the processes, capabilities and structures required to support it. This includes considering learning needs within government, across key government partners, and—importantly—with the community.

Think about useful check points to reflect on progress and opportunities to incorporate lessons into practice, strategy and policy reform. - Consider what’s required to foster a supportive learning culture. Because they are collaborative and relational, place-based approaches also require a level of readiness from government and community to work together—partners need the right mindsets, skills and resources, or be willing to build them.

In setting up MEL, government needs to appreciate that listening to and understanding the local community is a fundamental part of partnering with them. This requires intentional work to develop a culture of learning, with openness to sharing data, lessons and failures. - Identify appropriate governance structures to support strategic learning. Identifying systems and governance structures is another key planning step to ensure government supports a constructive learning agenda. Consider existing governance structures within community and government and identify possible gaps that may present barriers to ensuring learnings are captured and responded to in a timely manner. Ensuring the appropriate level of authorisation is in place in government is a critical step to support an adaptive agenda.

Key frameworks

- Building A Strategic Learning and Evaluation System for Your Organisation (FSG): The five key learning processes identified in this document are Engaging in Reflection, Engaging to Dialogue, Asking Questions, Identifying and Challenging Values, Assumptions and Beliefs, and Seeking Feedback.

- The Victorian Government Aboriginal Affairs Framework and Self-Determination Reform Framework: You can use principles in these frameworks to review if you are sharing data at the right level of decision-making, influence, control and accountability.

- Triple Loop Learning Framework (PDF, 682 KB)

This framework considers three different levels of learning. It has been adopted in innovative settings to encourage complex problem-solving and enhance performance. The framework can support groups to be clear about what it is they are aiming to learn about:- Single loop learning: About adapting to environmental changes through action

- Double loop learning: Involves questioning the framing of our actions (including strategy, values and standards, and performance)

- Triple loop learning: Focuses on interrogating the greater purpose of work (including questioning policies, values and the mission or vision)

Measurement and indicator selection

Measurement and/or indicator selection is a key part of rigorous and deliberate MEL practice as it sets the parameters for data collection. A set of agreed upon measures and indicators can help to clarify what to focus on and the sorts of data required.

Data and evidence in place-based contexts

The types of evidence used to track progress with place-based approaches does not align with the commonly accepted evidence hierarchy in government. Indigenous knowledge systems, experiential knowledge and expertise (lived experience), practice-based evidence and qualitative research are some of the types of evidence that need to be given greater weight in understanding and measuring the impacts achieved through place-based approaches. Supplementing quantitative measures with these types of data can support a rigorous and fit for purpose approach to MEL, including by identifying contribution towards outcomes, meeting cultural sensitivity consideration, and supporting in-depth learning.

Key considerations

- Consider data access and feasibility of collection through several lenses. Place-based approaches often require use of public data, service data, and primary data. When developing measures and approaches data collection, consider:

- additional resource requirements (including data platforms and systems) to support collection, storage and analysis

- legal and ethical considerations such as data ownership and sovereignty

- barriers to accessing data and the role of government in addressing these

- any arrangements required to ensure PBAs can access and use data in accordance with legislative requirements.

- Ground measures in theory of change and MEL questions. As in other contexts, developing MEL questions can be a helpful step to ensuring needs are articulated and measurement selection is adequate and is a common planning step in evaluation. Your measures should reflect the current priorities of the initiative, and should link directly to the theory of change.

- Ensure measures align with the evaluation methodology and any accompanying analytical frameworks. A measure may only signal whether a change has happened, not who or what has influenced this change, or whether it would have happened anyway. Consider which evaluation methods are required to address challenges such as contribution (for example, contribution analysis and performance rubrics).

- Don’t choose too many. Given the many possible areas for measurement, it may be better to start with a moderate set of measures to avoid being overwhelmed. You can then address gaps in measurement as they are realised. To ensure purposeful measurement selection, it can be useful to clearly articulate their relevance to specific monitoring, evaluation and learning needs of key stakeholders over time.

Example measures and indicators

To help you develop effective measures and indicators, we have created a set of example measurement areas and further guidance on developing a measure and indicator set for your place-based approach which you can find at Appendix A. The example measures and indicators are mapped against a theory of change approach over time and cover a range of elements, including enablers, systems influencing outcomes, and impacts in place. The example measures and indicators draw on the evidence of what works in practice, including from place-based approaches within Victoria, nationally and abroad.

You can use these as a starting point to inform your development of measures and indicators in place-based contexts.

Appendix A also includes an indicator bank that can be used for further guidance and inspiration during this important step.

Key resources

- Shared measurement: Though not covered in this toolkit, shared measurement is an approach that has gained popularity in Collective Impact approaches.

- SMART criteria (PDF, 145 KB): The SMART criteria offers a framework for assessing the quality of indicator selection, particularly in quantitative contexts.

- Evaluating systems change results: An Inquiry Framework (PDF, 862 KB): The framework provides guidance on the questions that can be asked when assessing systems change efforts and can help with your thinking on what constitutes a ‘result’ when developing measures.

- Place-Based Guide: This guide provides advice, case studies, tools and resources to support the use of data for MEL.

Setting up MEL from First Nations viewpoints

The relationship and connection to Country and place remains fundamental to the identity and way of life of First Nations peoples. MEL in place-based work must be done in a way that strengthens connections between people and Country, through collaborative practices, as a mechanism for shaping and sustaining the shared visions, values and experience of community members.

Culture is critical.

- This involves firstly, and most importantly, centring the worldviews, knowledge and priorities of First Nations partners within MEL and supporting First Nations communities to confidently articulate, drive and measure their own success.

- Contextual factors and cultural considerations must move beyond mere demographic descriptions of communities recognising the historical factors that created power imbalances and inequities for First Nations Communities.

- First Nations leadership and ownership should be embedded across all phases of planning and implementation of MEL.

Key phases of MEL from a First Nations lens

These key steps were developed by Black Impact and the National Centre of Indigenous Excellence:

- Yarning:

Your river fishing journey begins with a yarn about going out on the river together. Everyone is excited and has different ideas about what the journey will be like.

First engagement, reviewing tenders and having a yarn about a potential job. - Planning:

Once you've agreed to take the journey together, it's time to plan. You'll need to decide who will be part of the journey, when to go, what to bring and how the journey is going to happen.

Decision-making about accepting the tender. - Gathering:

After you've planned your journey, you begin gathering your gear and preparing for the trip. You choose a suitable boat and prepare a list of items to bring wiht you.

Writing the methodology, preparing the budget and submitting the tender. - Preparing:

Your journey is about to begin. You pack your belongings in your boat and confirm your travel plans. You brief everyone on the risks and hte signs to look out for in the environment around you (such as birds that signal bad weather of a good place to rest).

Inception planning - Leaving:

You're in the boat and beginning your journey down the river.- You have some vital tools to assist you: a mud map that a few of the mob have drawn up (theory of change) and guiding landmarks such as trees and river bends (key evaluation questions)

- You also have four other essential items for a successful trip:

- ethics

- data storage

- local experts

- data collection tools.

- Doing:

You've found a great spot on the river to stop and fish. You cast your rods and start fishing. As you catch fish (data sources) you store them in your esky.

Implementation and data collection. - Thinking:

It's now time to prepare the catch. You use your tools to remove the scales and prepare the fish for cooking.

Analysis, sense making and cleaning data. - Sharing:

The fish has been prepared and is ready to cook over an open fire. You cook the fish over hot coals to share with the group.

Reporting and sharing back data and findings. - Reflecting:

Everyone gathers together to share the meal and reflect on the journey. You think about how the fish tastes and your experiences along the river. You think about what you would do different next time and what you would do the same.

Reflecting learning.

When working with First Nations communities, it is important to:

- Recognise the importance of culture in MEL as it underpins values, processes, findings and, ultimately, outcomes. It is impossible for MEL to be meaningful to a community if the worldviews that underpin the approach to MEL are not expressly acknowledged and questioned.

- Understand what data sovereignty means to the First Nations communities you are working with and how to operationalise it.

How culture influences MEL

MEL Phase: Engaging

How Culture Influences the Work:

- How we see, experience, understand an issue/opportunity

- How we perceive a particular project

- How we view its relevance and importance to us

- Whether we feel respected, welcomed and safe to participate in it

- Whether we trust it will be done ‘the right way’ and that our voices will be heard

- How we participate in a project, what we share, with whom, how, when

What that Influences:

- Timeframe

- Relevance

- Relationship

- Respect

- Power

- Participation

MEL Phase: Framing

How Culture Influences the Work:

- How we understand/define an issue/opportunity

- What we value as being a desirable outcome, what we give primacy or priority to

- How we define “the right way” of doing things, how we make decisions

What that Influences:

- Perception

- Priorities

- Decision making

MEL Phase: Sensemaking

How Culture Influences the Work:

- What knowledge we bring and how that is conveyed

- What criteria we apply to make decisions or determine success

- What forms of evidence we pay (most) attention to

- How we explore and test ideas and perspectives

- How we manage conflicts and difference

What that Influences:

- Knowledge

- Evidence

- Analysis

- Interpretation

MEL Phase: Communicating

How Culture Influences the Work:

- How we convey and share information

- What is said, what is not said, by and to whom

What that Influences:

- Language

- Meaning

First Nations approaches to measurement

To be successful, a place-based approach should take the unique characteristics, challenges and hopes of a place and turn them into a shared vision or plan. While a vision and plan provide something tangible for cross-cultural partners to work towards, this fails to acknowledge that the vision rests within the expression and relationships people have with Country and place; and that there may be diverse experiences of Community, and thus approaches to influencing change and measuring change.

Some questions that may be considered by First Nations leaders and place-based partners when identifying measurement areas include:

- What were the things that happened that brought us together?

- Why did we decide that this was important for our Community?

- How would we describe what we are doing in our Community?

- What would we like to achieve?

Truth indicators are a valid and robust form of evidence and measurement that value and amplify the experience of First Nations peoples. Such an approach moves away from dominant culture approaches to research and evaluation, and moves to Traditional First Nations practices of oral, visual, and expressive forms of data. Utilising truth indicators is an opportunity for First Nations peoples to record evidence and share stories about our Culture, heritage, and history with the broader community.

Mayi Kuwayu - Cultural indicators

Mayi Kuwayu is a longitudinal study that surveys a large number of First Nations peoples to examine how culture is linked to health and wellbeing.

It is a First Nations controlled resource that aims to develop national level cultural indicators to inform programs and policies.

Study data may also be accessed by submitting a request to the Mayi Kuwayu Data Governance Committee for consideration.

Planning in practice: Building Foundations for First Nations Data Sovereignty: Ngiyang Wayama Data Network

What is this case study about?

A community-led data network which was established to progress data sovereignty for the local Aboriginal community in the Central Coast of NSW.

What learnings does it feature?

The case study describes Ngiyang Wayama’s practical approach to data based on a set of outcomes identified in their data strategy for the region.

Why have we included this case study?

To illustrate an example where principles for Aboriginal data sovereignty have been applied to data governance in a process involving government stakeholders.

Where can I find more information to help me apply these tools?

- Ngiyang Wayama Data Network

- OCCAAARS Framework - outlines principles of First Nations data sovereignty.

(See Appendix C for information on the above tools)

Case study

Overview

The Ngiyang Wayama (meaning ‘we all come together and talk’) Data Network works with the Central Coast Aboriginal community to increase their data literacy skills and confidence with the aim of achieving data sovereignty. The Network developed the Central Coast Regional Aboriginal Data Strategy which focuses on the outcomes below:

- Identify regional data needs through annual surveys to identify priorities across the region for different cohorts and determining a set of success measures that reflect their priorities

- Establish a regional data set by conducting a community data auditing and the development of a shared measurement framework to facilitate better data sharing across partners in the region.

- Develop data skills capacity within the region through data fluency training and in doing so, increase awareness of the value of data and gain buy in from the community.

Key considerations for Government

- Aboriginal data governance and clearly defined principles for Aboriginal data sovereignty should be established within Aboriginal place-based work as a whole, to protect and support all decisions, actions and impacts for Aboriginal peoples, including the way evaluative thinking is held in practice.

- Capacity building and learning for community members is critical and enables them to also gain insights into the workings of government.

Planning in practice: Guiding principles for MEL – Hands Up Mallee’s (HUM) MEL principles

What is this case study about?

This case study is about Hands Up Mallee (HUM), a place-based approach which works in partnership with the community, local service providers, agencies and three levels of government to improve outcomes in the community for 0-25 year olds.

This case study profiles the role and benefits of developing principles for MEL during the design phase of HUM’s MEL approach.

It has relevance for those designing MEL in complex contexts and in collaborations with divergent MEL interests.

What tools does it feature?

Outlines a collaborative approach taken to develop MEL principles.

Why did we feature this case study?

The case study has relevance for those designing MEL in complex and collaborative contexts and where there is divergence in MEL interests. By including principle development as a step in MEL planning processes, priorities can be explored and there is an explicit opportunity to collectively agree on an approach to MEL.

Case study

Overview

In 2021, HUM undertook a participatory process with collaborating partners to develop their MEL framework, which will guide learning and improvement and the building of an evidence base of HUM’s impact for the next fifteen years.

As part of this, HUM partners developed a set of shared principles and ‘lenses’ that identify their ways of working and what is important when implementing MEL.

Stakeholders participated in a facilitated co-design process that involved deep listening, iteration, and the weaving together and reconciling of diverse perspectives.

The conversation centred around the question: ‘what would good MEL look and feel like?’ for their partnership, ambitions, and context. This included considering the ‘whole’ collaboration as well as the diverse stakeholders and organisations interests and MEL needs.

HUM partners determined that they want MEL to be authentic, relevant, rigorous, and designed to fit available resources.

HUM's MEL Principles:

- Use data and evidence, both numbers and stories, for purpose/ action and to amplify our impact.

- Ensure Aboriginal communities and partners are participating and leading, and their rights for self-determination are supported.

- A culture of two-way learning for better understanding.

- Value and include the diversity of community experiences and perspectives to inform decision-making, learning, and evaluation.

- Participatory and creative approaches to build engagement, trust, and agency.

- Share data and findings in accessible, timely, and usable ways.

- Balance community and funders needs.

- Gather data and stories in ethical and respectful ways.

- A shared commitment to MEL over the long term.

Development Lenses:

The principles were then translated into a set of development lenses for their MEL framework. The six important elements of MEL identified were:

- Collaboration: Relationships, agreements, shared vision and measures

- Tracking impact: Timely, accessibility, useable and cyclic measurement, evaluation and reporting

- Community voice: Bringing community expertise, data and research together to inform planning

- Data storytelling: Being informed by data and storytelling to improve two way understanding

- Data sovereignty: Ethical and culturally appropriate gathering and use of data and stories

- Continuous and shared learning: Capacity building with internal and external expertise

Benefits for MEL:

The principles and development lenses are a testimony of HUM’s shared values and help HUM guide MEL implementation so it is inclusive and draws on multiple knowledge sources. This includes a combination of community voices, data, and research.

In the short-term: the participatory process was valuable for partnership strengthening and influenced the measures, data collection, tools, and learning of their shared MEL approach.

In the longer-term: the defined ways of working and development lenses will help HUM partners navigate the complexities of MEL implementation. They will also provide a way for the collaboration to keep accountable to, and routinely reflect on, the extent to which they are upholding their MEL principles in their social impact efforts.

Success factors:

- Adopting a participatory and iterative approach driven by listening and hands-on design by partners.

- Creating space for open conversations and investing in building MEL capacity and leadership locally through MEL coaching run in parallel to the design process.

- Working together on the MEL principles and lenses required a shift from programmatic and organisational thinking by individuals, to a ‘systems’ approach and a focus on what was important for MEL as a collaboration and for community.

Doing MEL

This section contains a selection of case studies and guidance to introduce you to new MEL approaches and explore how they are being implemented in practice with local communities. While a range of approaches are covered, this section is unlikely to provide enough detail to help you determine whether or not they are appropriate for your particular context. Where possible, additional resources are included to help you better determine what is applicable to your work.

Monitoring Example: Latrobe Valley Authority

Who is this case study about?

This case study is about the Latrobe Valley Authority (LVA); a place-based approach that intentionally partners with the local community to address complex challenges and support economic and social development across the Latrobe Valley. This spotlight focuses on LVA’s implementation of an impact log for staff to measure change and see the outcomes of their work.

What tools does it feature?

The case study features an impact log, which is a low-burden monitoring and evaluation tool used to capture reflections and gauge the influence of a program or initiative.

Why has this case study been featured?

The impact log continues to help LVA to record direct responses from the community about their work and map this over time in an efficient manner. It also helps them to capture impact for communication to executive leadership and ministers.

Where can I find more information to help me apply these tools?

Case study

Introduction

An impact log is a low-burden tool used to collect

day-to-day data to capture outcomes as they occur. An impact log works as a simple vessel for organised data. Those submitting data can respond to a few standard questions in a survey or enter data directly into a table (such as on Excel). LVA regularly use an impact log to support their MEL work. Given the complex, wide reaching and collaborative nature of their work, an impact log offers a way of capturing emergent outcomes in real-time, from across their numerous projects and programs.

LVA’s impact log is mapped alongside their behaviour and system change framework, which trains staff to think evaluatively and be alert to behaviour change occurring at a high level. LVA staff use this framework to guide their entries. The impact log is incorporated into the day-to-day work of LVA staff and stakeholders, allowing for real-time data and responses to be collected. Although designed to be an internal tool, where possible LVA staff make their entries reflective of community voice, by entering information drawn from conversations with community members and capturing reflections of those in the field.

LVA promotes the impact log by reminding staff about the tool in meetings, and regularly touching base with their funded bodies to share stories of growth and impact.

Application

The impact log has added value across the following areas for LVA:

- Learning and improvement: Able to use the information recorded to inform decisions about their work (enhance what is working well or improve certain practices).

- Identify and communicate early signs of change: Acts as a central log for stories of change and mindset shifts that can be leveraged for communications purposes as required – including for government stakeholders and the community.

- Lay foundations for rigorous evaluation studies down the track: Comprehensive studies can be conducted to substantiate and validate outcomes recorded in the impact log. This analysis can in turn contribute to learning, storytelling and overall accountability.

- Capturing community voice: Allows people to share their experiences firsthand, enabling the community to be the storytellers of their own experience.

- Coordinating diverse viewpoints: Creates the opportunity to have a central repository for many contributions, including the perspectives of their various partners working in place.

Reflection/impact

The impact log has proved to be a rich tool for LVA, allowing them to draw valuable insights about the impacts of their work. Despite this, some challenges have emerged, including:

- Driving uptake: Generating momentum for staff to contribute to an impact log can be challenging, as it is an ongoing process, and can require time investment and a level of interpretive effort. One way that LVA has sought to drive uptake is by using innovative ways to prompt staff to access the log, including by developing a QR code that links directly to the survey.

- Capability and needs-alignment: In order for impact log entries to be reflective of community voice, staff need to have insight into what is relevant and engaging to community. Building trust and investing in partnership work are two ways to do this, however they both take time. Further to this is the challenge of aligning the needs of those using the tool (LVA staff) with broader evaluation purposes. Questions need to be carefully framed so that they resonate with staff while also supporting evaluation goals and additional training may be required to ensure fidelity of use.

- Privacy and accessibility: An impact log can at times collect sensitive information, so good privacy controls are important. Accessibility is also vital, so that staff can easily contribute to and review the log. Finding a platform that is easy to use and accessible across a range of levels, while also meeting government security standards and allowing for detailed analysis to be conducted in the backend, is an ongoing challenge.

LVA impact log questions

Why?

We often struggle to capture and understand the less tangible impacts and changes associated with the influence of our work.

What?

A story-based tool that seeks to capture place-based examples of changes across system.

How?

Eyes and ears: record conversations or evidence that suggests that the system may be changing.

Which area(s) has the impact changed?

- Innovation (production, processes or services)

- Knowledge (research or information)

- Relationships

- New practices

- Behaviours or mindsets

- Resources and assets flow

- Value/benefit for partners, community or region

- Organisational structures

- Policies

What is the impact?

(what changed)

How did this change happen?

(what contributed to this change)

Level of contribution?

- The change would not have occurred but for the contribution made

- It played an important role with other contributing factors

- The change would have occurred anyway

Who contributed to this change?

Who benefits from the change?

- Individuals

- Group/network

- Organisation/industry

- Community

- Region

- State

Do you have any supporting evidence?

Evaluation Example: Contribution Analysis study in Logan Together

Who is this case study about?

This case study profiles ‘contribution analysis’ which is the evidence-informed process of verifying that an intervention, way of working or activity has contributed to the outcomes being achieved. Approaches for evaluating contribution range from light to rigorous, and this example is the latter. Contribution analysis plays an important part of measuring social impact—tracking outcomes alone will not provide a strong impact story.

What tools does it feature?

This case study outlines the steps undertaken for a contribution study. The study utilised quantitative and qualitative data, theory of change, contribution assessment and strength of evidence rubrics. The study was undertaken by independent evaluation specialists.

Why has this case study been featured?

It is an example of a rigorous approach to assessing contribution where attribution cannot be ascertained quantitatively.

Where can I find more information to help me apply these tools?

Case study

Overview

During 2021, the Department of Social Services (DSS) commissioned a contribution analysis on the Community Maternal and Child Health Hubs in Logan (‘Hubs’). The study aimed to evaluate the contribution of the Collective Impact practice on the health outcomes achieved.

The Hubs aim to increase access and uptake of care during pregnancy and birth for Logan women and families experiencing vulnerability. They cater for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, Māori and Pacific Island women, young women under 18 years old, culturally diverse women, refugees, and women with significant social risk. The Hubs and the supporting Collective Impact initiative Logan Together are based on the traditional lands of the Yugambeh and Yuggera language speaking peoples in the Logan City area, near Brisbane.

The study was undertaken by Clear Horizon, in close partnership with Logan Together and DSS. The study is one of the first of its kind in the Australian context, and provides a well-evidenced and rigorous assessment of the role of Collective Impact practice.

How the study was done

The methodology was informed by Mayne’s Contribution Analysis and used an inductive case study approach. Determining the causal links between interventions and short, intermediate, and long-term outcomes was based on a process of establishing and evaluating a contribution hypothesis and building an evidence-informed contribution case.

The methodology required first evidencing the outcomes achieved and then investigating the causal links between the ways of working and activities with the results. The key steps included:

- Developing a contribution hypothesis using a theory of change approach

- Data collection and reviewing available quantitative and qualitative data

- Developing an evidence-informed contribution chain and assessing alternative contributing factors

- Developing and applying rubrics for rating contribution and strength of evidence

- Conducing verification and triangulation.

Benefits

The findings have been useful for DSS and Logan Together to demonstrate the effectiveness and impact of Collective Impact practice. It has helped governments demonstrate the contribution of the Collective Impact practice, which was verified to be an essential condition for the health outcomes being achieved.

The contribution analysis showed that the Hubs, and subsequent outcomes (including clinically significant outcomes for families involved), would not have happened without the Collective Impact practice.

Challenges

One of the challenges of a rigorous contribution analysis is that there are multiple impact pathways by which interventions can influence outcomes, and many variables and complexities in systems change initiatives.

Detailed contribution analysis take time, stakeholder input, and resourcing to ensure rigour and participatory processes. Communicating the contribution case can also be challenging if the causal chain is long and complicated, and when there are many partners involved.

Keep in mind there are other ‘lighter touch’ contribution analysis tools, such as the ‘What else tool’, that help make this important methodology feasible and accessible within routine evaluation without the need for specialist skills.

Testing and verifying contribution

Using the multiple lines of evidence, a ‘contribution chain’ was developed and tested across different levels of the theory of change. The contribution chain shows the key causal ‘links’ along the impact pathway for an intervention. The simplified steps to evaluating the contribution for the Community Maternity Hubs is shown below.

The data sources included quantitative metrics available from Queensland Health, population-level datasets provided by Logan Together, and a small sample of key informant interviews and verification workshops. Two evaluative rubrics were used in the methodology, one to define and assess contribution ratings and the other to assess the strength of evidence used to make contribution claims.

Contribution chain example, “Community Maternity Hubs”.

- How the collective practice influenced the conditions and changes in the system—and how this contributed to developing the Hubs. This included assessment of the collaborating partners and the different roles they played. Levels of change include:

- Hub intervention and systems changes

- Collective impact conditions, including

- Systems approach

- Inclusive community engagement

- High leverage activities

- Backbone and local leadership and governance

- Shared aspiration and strategy

- Strategic learning, data and evidence

- How the Hubs model and delivery are contributing to outcomes for target cohorts using the Hubs was assessed. Levels of change include outcomes for Hub users and target cohorts.

- Analysis then focused on if the Hubs’ outcomes are contributing to population level changes for women and babies in Logan. Levels of change included population-level changes across Logan.

Challenges and opportunities for economic assessments in complex settings

This section outlines the commonly used methods for economic assessment and outlines limitations of these methods when applied to place-based contexts. It then introduces an innovative approach to assessing value for money that accounts for some of these limitations and presents a key set of considerations when approaching value assessments in place-based contexts.

Commonly used methods for economic assessments

Economic assessment is the process of identifying, calculating and comparing the costs and benefits of a proposal in order to evaluate its merit, either absolutely or in comparison with alternatives (as defined by DJPR). All economic methods seek to answer a key question: ‘to what extent were outcomes/results of an initiative worth the investment?’

- Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) is a widely used method to estimate all costs involved in an initiative and possible benefits to be derived from that initiative. It could be used to provide as a basis for comparison with other similar initiatives.

- Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) is used as an alternative method to cost-benefit analysis. It is used to examine the relative costs to the outcomes of one or more interventions. CEA is used when there are constraints to assessing monetise benefits.

- Social Return on Investment (SROI) (PDF, 1,190 KB) uses a participatory approach to identify benefits, especially those that are intangible (or social factors) and difficult to monetise.

Key takeaways

- All methods have challenges and subjectivities. When aiming to consider/assess value for money, be open to using approaches and methods that can best suit your needs.

- When considering value for money of place-based approaches, assessments need to:

- accommodate changing contexts with emergent, unpredictable and complex outcomes

- enable genuine learning with stakeholders throughout implementation

- recognise that sometimes failure is necessary because there is a level of risk and failure in particular project—need to learn from this.

- maintain transparency and rigour around how economic judgements/assessments are made

- involve stakeholders and particularly those who will be affected by evaluation—in the spirit of participatory approaches in PBAs.

Examples of application

Several place-based initiatives have used a mix of qualitative, quantitative and economic methods to determine the extent to which the initiative achieved value for money.

- Maranguka Justice reinvestment in Bourke, NSW (PDF, 704 KB).

Conducted an impact assessment to calculate the impact and flow-on effects of key indicators on the justice (e.g. rates of re-offending, court contact) and non-justice systems (e.g. improved education outcomes, government payments). - The Māori and Pacific Education Initiative in New Zealand (PDF, 3.8 MB).

Conducted a value for investment which included tangible (e.g. educational achievement and economic return on investment) and intangible dimensions (e.g. value to families and communities, value in cultural terms) of value. - An economic empowerment program for women in Ligada, Mozambique (PDF, 2.7 MB).

Used a value for money framework which used a mix of quantitative evidence and qualitative narrative to assess performance. The approach factored intangible values (such as self-worth, quality of life) when measuring impacts. - ActionAid (PDF,1,678 KB).

Developed an approach driven by participatory methods to assess value for money which involved community members in the assessment if value for money.

Limitations of using purely economic methods

Economic assessments can present some challenges including difficulties in:

- monetising social benefits in a meaningful way and in an environment where benefits are evolving and occurring over a long timeframe

- defining value when there are different perceptions of value held by stakeholders involved in place-based initiatives

- addressing equity in terms of the segments of the population who may not have been impacted by the intervention

- ascribing monetary value to a particular pool of funding can be difficult when outcomes are a result of a collective effort

- supporting learnings on factors that influence the effectiveness of a place-based approach in responding to complex challenges.

An innovative method for assessing value for money

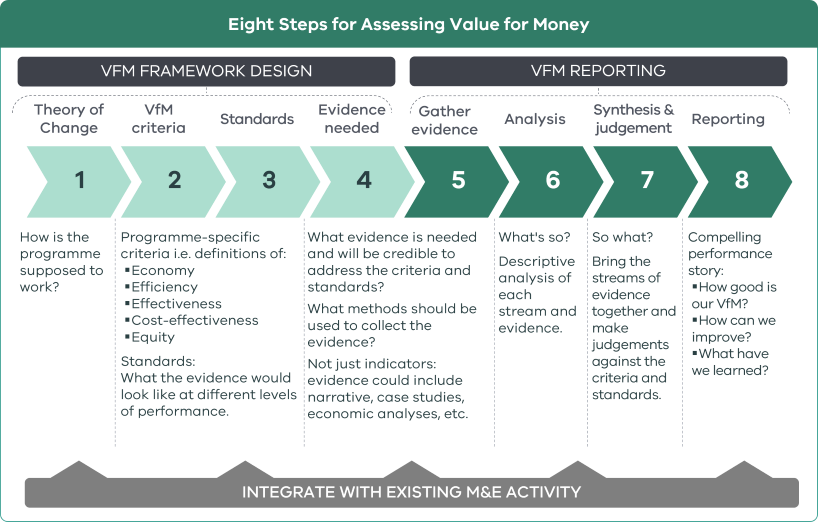

There are new methods emerging in this space to counter the limitations of mainstream economic methods such as Julian King’s Value for Money (VfM) framework which brings more evaluative reasoning in to answer questions about value for money.

The VfM framework encourages the definition of value within the context that is relevant to the stakeholders and uses a process to judge what evidence suggests to reach evaluative conclusions about the economic value of an initiative.

The approach sets out eight steps across the designing, undertaking and reporting of a VfM assessment (see diagram to the right). The approach combines qualitative and quantitative forms of evidence to support a transparent, richer and more nuanced understanding than can be gained from the use of indicators alone.

The VfM framework is embedded within the MEL design for efficiency and to ensure conceptual coherence between VfM assessment and wider MEL work.

Eight Steps for Assessing Value for Money

Source: OPM’s approach to assessing Value for Money (PDF, 2.5 MB) (2018) developed by Julian King and OPM’s VfM Working Group

VfM Framework Design

Step 1: Theory of Change

How is the programme supposed to work?

Step 2: VfM criteria

Programme-specific criteria i.e. definitions of:

- Economy

- Efficiency

- Effectiveness

- Cost-effectiveness

- Equity

Step 3: Standards

What the evidence would look like at different levels of performance.

Step 4: Evidence needed

What evidence is needed and will be credible to address the criteria and standards?

VfM Reporting

Step 5: Gather evidence

What methods should be used to collect the evidence?

Not just indicators: evidence could include narrative, case studies, economic analyses, etc.

Step 6: Analysis

What's so?

Descriptive analysis of each stream and evidence.

Step 7: Synthesis & judgement

So what?

Bring the streams of evidence together and make judgements against the criteria and standards.

Step 8: Reporting

Compelling performance story:

- How good is our VfM?

- How can we improve?

- What have we learned?

Learning Example: The Healthy Communities Pilot - A layered approach to collective learning and protection of community defined data and knowledge

First Nations learning and reflection cycles are embedded in Cultures and worldviews. Learning and reflection is conducted all the time, such as over a cuppa, when driving between places or when having a yarn after an event. Place-based work is dynamic and it is vital to reflect on its progress as a collective (in a more formal manner), and to make strategic decisions as to how to progress forward.

The use of truth telling and First Nations tools such as Impact Yarns continue to be centred in learning and reflection. The Impact Yarns tool provides an approach to gathering truth telling, sharing truth telling, layering collective Community voice and then centring First Nations sense-making and sovereignty for local decision-making. This tool covers all aspects of evaluative practice.

The Healthy Communities a pilot focuses on building community and strengthening culture and kinship with the aim of improved health outcomes and behaviours for First Nations communities. The pilot is led by four Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (ACCOs); Goolum FM Aboriginal Cooperative, Budja Budju Aboriginal Cooperative, Moogji Aboriginal Corporation and Rumbalara Aboriginal Corporation.

The Impact Yarns tool provides an approach to gathering truth telling, sharing truth telling, layering collective Community voice and then centring First Nations sense-making and sovereignty for local decision making. This tool covers all aspects of evaluative practice.

The evaluation of the pilot embeds First Nations sovereignty and truth telling in the evaluation process by using Impact Yarns. Impact Yarns enables staff, project participants and Community to identify the outcomes/changes that they felt were impactful during the pilot. Local Cultural and data governance mechanisms were set up to guide the collective sense-making process and to engage in First Nations thought leadership to identify which Yarns were most impactful and why.

First Nations Data governance also supports and protects the knowledge that was gathered and shared during the evaluation process. This layered approach to data interpretation, governance and decision-making sought to protect Cultural knowledge and wisdom, and ensure that the narrative of Community and First Nations peoples was well authorised and contextualised.

Learning Example: Go Goldfields

Who is this case study about?

This case study is about the Go Goldfields Every Child Every Chance initiative which is aimed at ensuring every child in Central Goldfields has every opportunity to be safe, healthy, and confident. The case study focuses on the launch of the ‘Great Start to School for All Kids’ (GSTS) project and the learning and reflection cycles throughout its implementation.

What tools does it feature?

Action-oriented learning workshops.

Why has this case study been featured?

The case study shows learning workshops can be central to place-based approaches. In this example, workshops provide a forum for partners to work collaboratively to understand the key problems that needed to be addressed in the Central Goldfields area. They also provide partners the opportunity to develop a plan that ensures the project responds to community needs and adapts to meet the evolving needs of the community, addressing emerging issues as they are identified during project implementation.

Where can I find more information to help me apply this tool?