Key findings

- Providers of cohort trials and case management reported that participants have been demonstrating high levels of engagement compared with their experience facilitating mainstream programs.

- Some participants have reportedly begun to understand the effect that their violence had on others and began to take responsibility for their behaviour.

- Participants acknowledged that they would need to continue to work on implementing these strategies in order for them to become ‘learned behaviours’.

- The programs are contributing to a greater level of risk management of people who use violence, particularly those with complex needs.

- People who experience violence reported that the support they received had helped them to feel less isolated, and a number indicated their feelings of safety had improved.

6.1 Introduction

The data collection process identified some early client achievements as a result of participating in the cohort trials and case management. The achievements identified are limited in breadth and nature due to the short amount of time that has passed since the commencement of the programs.

Early achievements of cohort trials and perpetrator case management are explored in this section in respect to three key areas:

- attendance, retention and engagement of people who use violence in perpetrator intervention

- people who use violence’s insight into their violent behaviour

- the behaviour change strategies of people who use violence

- outcomes for people who experience violence.

6.1.1 Data collection limitations

This section predominantly draws on data collected from the interviews with people who experience violence and people who use violence, and the data collection tool.

The data collection tool required providers to ask people who use violence and people who experience violence a short series of questions related to their perceptions of and current use of violence [1] at the commencement and exit of the program.

Of the data returned via the data collection tool, outcome data was only provided for a subset of individuals [2], which was particularly small for people who experience violence. Therefore, these results only represent a small sample of participants involved in the programs. Additionally, while the results of the people who use violence and people who experience violence are reported together, the responses for each group were aggregated, and therefore should not be interpreted as linked between partners or family members.

Secondly, the outcomes (entry) data is intended to be self-reported by people who experience violence and people who use violence. Training was provided by FSV to providers to assist them in incorporating asking people who use violence and people who experience violence these questions into their practice. Providers were advised that in circumstances where the participant was not available to be asked the question directly, they could use their own judgement to respond to the outcome question. There is likely to be variation between a participant’s perception of their own insights or behaviour, compared with the provider’s, particularly noting that a number of participants were either near completion or had completed the program at the point of data collection, and were asked to report retrospectively. One example was given from a provider regarding this issue, whereby one participant believed that he was insightful about his behaviour at the start of the program, however he would have been assessed as having no insight.

6.2 Attendance, retention and engagement

The cohort trials and case management were funded and designed to increase the number and range of people who use violence who could engage with perpetrator intervention. Whilst availability of programs is the first, and important, step to prevention of family violence through perpetrator interventions, continued engagement and retention of participants in the programs is crucial to their success.

6.2.1 Attendance and retention

With reference to the demographic data from the data collection tool, reported in Chapter 5, there are positive signs that a greater diversity of people are now able to access perpetrator interventions. This is also supported by anecdotal evidence from providers. For example, case management providers are now working with people who use violence who had previously attempted to participate in mainstream MBCP but found it unsuitable for their circumstances or were excluded by providers. Furthermore, many participants disclosed in interviews for this evaluation that they were receiving support for the first time. The data collection tool showed that only 13% of people who use violence undertaking a cohort trial had previously attended a MBCP [3]. For case management, 11% of people had previously attended a MBCP [4].

A number of cohort trial providers noticed that retention rates were higher in cohort trials compared to mainstream MBCP. They reported that this was a consequence of increased resources being available to achieve more regular contact with participants, particularly participants who can typically be challenging to engage with. They also noticed that when men could not attend a session they would text in advance and let the facilitator know the reason, which was uncommon in their experience. The provider of the women who use force cohort trial found that women were continuing to attend the group when they were experiencing crises in their lives and furthermore women in crisis were arriving early to the sessions.

The design features outlined in Chapter 4 contributed to the strong retention, including closed rather than open groups, and the creation of strong relationships between facilitators, participants and group members.

Analysis of the data from the data collection tool shows that the average program participation rate was 60% for case management and 72% for the cohort trials. This is not an indication of overall program completion, but just indicates the average proportion of available sessions that were attended, at the time of data collection.

6.2.2 Engagement

A number of providers reported that participants have been demonstrating high levels of engagement compared with their experience facilitating mainstream MBCPs. This was evident not just through increased attendance levels, but by participants willingness to participate in the group activities, and being relaxed and ‘opening up’ in sessions.

Key enablers of positive engagement with the program included:

- Personal development - including the desire for self-understanding and emotional regulation. A number of participants spoke of wanting to be a ‘better person’.

- Family reasons – the desire to improve their relationships and communication with family, including their children or a partner or ex-partner. Some participants mentioned that they did not want their children to emulate their own behaviours.

- External motivators – a number of participants indicated that they perceived their involvement in the program would reflect positively on them, which would assist with legal proceedings or child custody negotiations.

Some identified barriers to engagement included:

- the negative stigma associated with perpetrator interventions

- a lack of preparedness to change behaviour or take responsibility for violent actions

- a lack of awareness about the program and how it could help them, resulting in uncertainty and trepidation to become involved

- the time commitment of the program, and the inability to balance participation with competing demands such as work, family, and for some, legal cases

- dissociating from person who uses violence – a unique barrier for people who experience violence related to having an ongoing association with the person who uses violence.

- if the person was mandated to attend, this sometimes reduced their willingness to engage, as they weren’t yet at a point where they had acknowledged their violent behaviour or the need to address it.

In some cases, there were concerns raised about the intention behind the motivation to engage in the programs. This related to whether the person was participating in the program in order to change their behaviour, reduce their violence, and improve their relationships, or whether there was a motive associated with wishing to be viewed positively by others.

As mentioned in Chapter 5, for CALD cohorts there is still a barrier to understanding what constitutes family violence, and this contributes to a lack of readiness to change behaviour. There was anecdotal evidence that this cohort were motivated to participate so that they could remain with their family, and reduce their contact with the justice system.

A lot of migrants that come from the country – they don’t know their own – what do you call it? The rules of the country. They’re new. They don’t even know that it’s a crime, if they’ve done something wrong here, you know? And you could have a heated argument and that could end up in court. A lot of these – it’s not, like, physical violence, or things like that. You’ve had an argument, or something like that, and that’s considered family violence, you know?

In the context of the Aboriginal cohort, connection to country and community involvement has been a significant factor in providing a culturally appropriate and engaging service for this cohort, as discussed in Chapter 5. However this close connection to community has raised concerns in some instances where participants may perceive their involvement in the program as a means of developing a positive profile in the community, especially through association with the local case workers who are well respected community members. This shows that there is a need to address motivation for change as part of the program, framed in the context of firstly addressing violent behaviours, with positive community connections as a secondary benefit.

Another bonus too, probably indirectly, is living here in [Location], for me the type of person [Case Worker 1] is and with what I'm doing and the situation I'm in, I can be anywhere and I have people say, "Hey, how are ya?" and I say, "Oh hey, how you going?" I don't know who it is. Or so and so. But they know who I am and they know what I've been doing, know where I'm going to. So actually outside of the group the people that I've met that are in other organisations that are happy to say "Hi". And that's awesome.

6.2.2.1 Exit planning

One issue identified with engagement has been around exit planning and the role of ongoing engagement and support for people who use violence. There has not been a clearly communicated and consistent approach to exit planning among providers. In many situations people who used violence reported they had not had a conversation with their case manager or group facilitator regarding when their support would end. This has meant people who use violence themselves were not always clear on the end of their engagement, and what they could do if they felt they required more support.

In contrast, there were other examples where providers communicated to people who use violence that while official support had been finalised, they could get back in touch with the provider. This has assisted people who use violence become more aware of the supports available to them, so they know where to go for help if needed. Some Aboriginal providers have established yarning groups as a means of providing a less intensive ongoing support to people who use violence.

It's just good knowing I can ask and I can receive, you know what I mean? Normally you'd be sitting around and you wouldn't know what to do. You wouldn't know how to find people to help.

6.3 Insight

Acknowledging the current short-term analysis of the programs, increased insight into their violent behaviour is an early indicator of the change process for people who use violence. It is common that participants commence perpetrator intervention programs with limited acknowledgement of responsibility for their actions. They may claim that their behaviour was the fault of the people around them, and that they were the victim in their situation. However, anecdotal evidence shows that through program education and activities, some participants began to understand the effect that their violence had on others and began to take responsibility for their behaviour.

6.3.1 Awareness and understanding of family violence

Several service providers, notably the two trials working with Aboriginal cohorts, reported they focused on increasing understanding and knowledge of different types of family violence with people who use violence. Anglicare reported they specifically ask the father to name the type of violence they use, to increase understanding that their behaviour constitutes violence. Similarly, BDAC reported that after several weeks of the program they dive deeply into understanding what family violence is, and the behaviours that comprise family violence. They emphasise that family violence is not just physical, but also emotional, cultural, financial and social. In this way, they reported it broadens people who use violence’s understanding of their controlling behaviour.

This work appears to have had some effect on people who use violence recognising that their behaviours constituted abuse. This change in understanding was most prevalent among participants who were previously unaware that non-physical actions could be violent, such as yelling or emotional abuse.

I’ve always been aware of family and domestic violence. It’s always been on my radar. I just never knew the intricacies of it. I never knew how small these little things are that we do that contributes to being a part of the violence realm. So, I think it’s broadened my knowledge of what the violence realm is.

Increased understanding of what constitutes family violence was particularly apparent among those from the InTouch trial. People who used violence seemed to demonstrate greater understanding of what behaviour was family violence, however this was often couched in terms of the justice system and what was legal versus illegal. In contrast, the people who experienced violence from this trial did have an understanding that the behaviour was family violence, and used this language more commonly than the people who used violence.

No, I used to stop my wife “Don’t go there. Don’t go there. Don’t meet your friend. Don’t meet this friend.” Like this, yeah. I used to stop but not anymore because in group session they teach us you can’t stop legally, it’s violence. Even this is violence.

Some participants also indicated that the perpetrator intervention helped them to identify that they were, or had been, involved in a family violence situation. Interventions helped them to gain a deeper understanding of the dynamics involved in family violence, including its pervasiveness across all population groups.

Once you start the course is that you understand that family violence is not solely for one age group or one nationality, it can affect anyone of all different nationalities, cultures, ages, sexes, et cetera.

This increased awareness was also experienced by people who experience violence, many of whom had previously excused or minimised the abuse. Those interviewed reported that the family safety contact worker had helped them to acknowledge that family violence had occurred, and that they were not responsible for the violence they had experienced.

And my understanding of – more of just what family violence is. I think initially I didn’t even know that half the stuff that was going on in my life was down to family violence. I thought it was just oh, you know, part of a relationship. But the more I look back, the more I go… Jesus Christ, how long did I put myself through shit?

There were examples where the increased knowledge appeared to have equipped the person who used violence to use this knowledge to perpetrate violence. For example, they used language such as reporting they were ‘anxious’ to describe and justify their violent behaviour.

He didn’t have any insights, he didn’t have any acknowledgement, there was no apologies, there was no nothing. All he learnt from the men’s behaviour change program was that, ‘Oh, it’s my anxiety, that’s why I behave like that.’ …And he came, and he’s like, ‘Oh, I’ve had this revelation. I behave like that because I was anxious.’ That’s always been his excuse, that his anxiety has been a massive control mechanism in our relationship.

6.3.2 Understanding the impact of behaviour on others

Perpetrator interventions helped people who use violence gain insight into their behaviour through providing education on the impact of family violence. Gaining an awareness and understanding of other people’s perspectives of their behaviour was reported to be a key learning from participation in the programs. Some participants stated that they previously had not given much thought to how their actions would be perceived by others. For example, a few participants stated that they were unaware that raising their voice, or their mere physical presence could be intimidating for other people.

I'm 6'4”, I'm a big guy, and it would be scary for her in a sense of things, and I also didn't really realise that that much, but maybe that was probably the fact being that the size of me, and my voice gets quite loud, I can get very loud, would be terrifying to someone. I didn't know until [Case Worker] pointed it out to me.

I can be pretty intimidating if I need to be… what I’m finding out is that psychological side of things can even have a bigger impact on people. I’ve looked at people and seen that they’ve been scared of me, and I don’t like that...

I think I’ve got more compassion for other people now. I’ve got more understanding of other people, how they would feel if I was acting in an angry way, so to speak. He’s done well, he pulled me out of my shoes and put me in someone else’s shoes. He done a good job, he really did.

In some cases, this also extended to understanding the impact that family violence has on children. As noted above, some participants indicated that becoming a better role model for their children was a key motivator for their involvement.

I have two boys … a 15 year old and an 11 year old - it's really important for me to show them how to treat women… even being accountable for what I say to them… those little things that we might not think [have] an impact on our children because they're just kids, when they're things that they take into their future and their own personal experiences… It's changing a generation.

I do think he’s more aware of how his behaviour impacts particularly [Child], and obviously me, but particularly [Child]…so definitely I think it’s made him more aware of the impact of his behaviours. And we’ve managed to get to a point where he’s – where we’re going to have a financial settlement, which I never thought we’d get to. I do think I’ve definitely seen a change. It’s definitely not perfect or – and I anticipate there’s probably still going to be some difficult times in the future, but I have 100% seen some change.

This is supported by findings from the outcomes measures included within the data collection tool, where there was a higher proportion of people strongly agreeing that the person who uses violence understood the impact of their behaviour on others at exit compared to entry. This was the same for people who experience violence and people who use violence (see Appendix E). While people who used violence had higher proportions of people agreeing or strongly agreeing compared to people who experience violence, there was nonetheless a positive shift in the perception from both parties. There were more people who experienced violence who agreed or strongly agreed that the person who uses violence understood the impact of their behaviour at exit for the cohort trials compared to the case management.

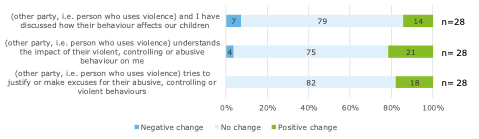

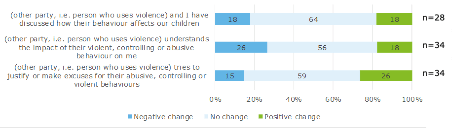

Between 14% and 26% of people who experience violence reported positive changes in the person who uses’ violence understanding of the impact of their behaviour at exit compared to entry (see Chart 6.1 and Chart 6.2). This was similar across both the cohort trials and case management. A higher proportion of people who experience violence reported negative changes in the case management programs compared to the cohort trials. In the case management trials, there was a similar proportion of people who experience violence reporting negative changes as there were positive changes. This may reflect the intensive nature of the cohort trials, which included both group learning to address behaviour and a case management component. In addition, it reflects the long-term nature of behaviour change.

Chart 6.1 Cohort trial, proportion of people who report changes in outcomes, people who experience violence

Chart 6.2 Case management, proportion of people who report changes in outcomes, people who experience violence

For the InTouch trial, participants focused on their increased knowledge of what constituted family violence, yet this had not necessarily translated into understanding the impact it had on others. As mentioned in 6.3.1, participants’ understanding and motivation for change was framed in the context of the justice system and keeping their family unit together, rather than because of the impact it had on their family. This is not a reflection of the program, but perhaps the level of readiness for change among participants, and a lower level of baseline knowledge regarding family violence. This reinforces the need to work with these communities.

A lot of migrants that come the country – they don’t know their own…The rules of the country. They’re new. They don’t even know that it’s a crime, if they’ve done something wrong here, you know? And you could have a heated argument and that could end up in court. A lot of these – it’s not, like, physical violence, or things like that. You’ve had an argument, or something like that, and that’s considered family violence, you know?

6.3.3 Taking responsibility for behaviour

There is mixed evidence on the extent to which people who use violence are taking responsibility for their behaviour, with many examples of this occurring while other examples of victim blaming persist. This is to be expected given the short-term nature of the programs, compared to the long-term process of behaviour change. This is discussed more in Section 6.4.

Through participation in the cohort trials and case management, some participants began to reflect on the negativity of their past behaviour. Many participants indicated that being part of perpetrator intervention allowed them to reflect on their past behaviour and actions, and recognise that it was wrong. Some participants talked of realising their behaviour was not ‘normal’, and others indicated they felt ‘ashamed’ or ‘embarrassed’ of their actions.

I didn’t realise how bad I was. I can’t apologise enough for it… [provider] made me realise how off track you are. You think it’s normal. I don’t know. I think it’s not normal going off at bank managers or going off at Centrelink or going off at your best mate… beating the hell out of your kids… It’s not normal, you don’t do that.

You feel ashamed of what you have done. You just look back and say ‘God, what did I do?’ I’m fully embarrassed of what happened...

The program, to me, is based on acknowledging your behaviour, acknowledging your part in the behaviour, and acknowledging your wrongdoing. Accountability is a big one. You’ve got to be accountable in order to change your behaviour and move forward.

Many participants talked of recognising a need to take accountability for their actions. Some participants noted that they were ultimately responsible for how they responded in certain situations. Participants stated they learned not to ‘minimise’ or ‘smoke screen’ their abusive behaviour.

I find myself explaining why things happen. But you’re not there to explain why something’s happened. You’re there to accept full responsibility for why things have happened. You’re not here to blame other people.

I’m reminded of the severity of the incident that I was involved in. As I didn’t believe it was so severe, but it didn’t matter… from severity of say 1 to very severe at 100 or extremely severe. It didn’t matter. I might have thought that I was probably around about 15. It doesn’t matter if it’s 15 or it’s 100, it’s the same thing.

While these examples are promising, data from the data collection tool and other interviews suggest there are still a large proportion of people participating in the programs who are not yet taking responsibility for their behaviour. A low proportion of people who experience violence strongly agreed or agreed that the person who uses violence does not justify their behaviour across both the cohort trial and case management (see Table 6.3 and Table 6.4). There were also continued examples of victim blaming and people who use violence not taking responsibility for their behaviour. This is discussed in more detail in Section 6.6. This does not mean the programs are ineffective, but rather these programs are needed to reinforce learnings over a longer time period to reflect the long-term nature of behaviour change. This is discussed more in Section 6.4.

6.4 Behaviour change strategies

Despite the early stage of implementation of the cohort trials and case management, there were reports that some participants were beginning to apply strategies in order to change their behaviour. This included examples given by service providers working with the participants, and self-reported behaviour change by participants themselves.

The main strategies used by people who use violence to subdue their behaviour included regulating their emotions, or removing themselves from a situation.

Learning how to regulate emotions was a key driver for participant behaviour change. Participants usually associated their change in behaviour with an increased ability to regulate anger, or by taking time to think before reacting. Participants talked of being calmer as a result of applying their learnings from the program.

I’m a completely different person now. I would just get angry like that and lose temper. But now I don’t know, I don’t know what happened to be completely honest. It just gone… yes, you are human, you get angry, but the extreme of that angriness is not that high. You know what I mean? It’s before… I think I was just sort of an animal or something... I’m sorry to say this...

Some participants mentioned that they learned to recognise when they were feeling a certain way (e.g. physical changes in their body as a result of anger). By regulating their emotions, they could lessen their propensity for violence. They also learned to separate actions from their emotions, for example, noting that whilst it might be normal to feel anger, it was important for them to be mindful of their behavioural response.

Usually my body starts shaking, I start sweating, I start pacing, my heart feels like I've got two hearts, like it's double beating or something. Yeah I just usually want to hurt the person really bad. But if something usually happens now it's just like I think about my future. I stop and actually realise well if I do this, if I act in this matter, then the outcome is going to be me in prison.

Well the strategies, like even just focusing on regulating my own emotions. Like I’m sitting there angry. It’s okay to feel the anger but it’s not okay to act out on it. So those sorts of things. It’s okay to feel sad but it’s still not okay to hit someone because you’re sad… how to feel your emotions in a healthy way and a safe way.

Another common strategy was to remove themselves from a potentially volatile situation. For example, participants would take time out to compose themselves whenever they felt upset or angry. This involved ‘walking away’ to find a quiet place, meditate, or distract themselves with physical exercise.

Strategies, is simple; if you're frustrated, or you're angry, stay away from the grog, stay away from anything that might stir it up, stay away from people, stay away from the person who's made you frustrated… he suggested to get a bit of paper and write down all this stuff on the bit of paper, and write it all down, and then screw it up and throw it out… very kind of handy – which really worked for me.

The meditation… That's been particularly helpful because I've been able to use it at home to relax from work, and sleep better.

Anecdotally, some providers commented on the potentially negative impact this can have on people who experience violence if they are not emotionally prepared for these changes in their partner, even when this is a reduction in violence. There may be cases where ‘abnormal’ behaviours on the part of the person who uses violence may cause the person who experiences violence to become ‘on-edge’ about what to expect, particularly if their partner typically presents with unpredictable behaviour that results in violence. One example given was when a person who uses violence chooses to ‘walk away’ from a situation, the person who experiences violence may perceive this as abandonment rather than a de-escalation strategy. This demonstrates the importance of the family safety contact worker being able to manage expectations with the person who experiences violence, and communicate potential changes in the behaviour of the person who uses violence.

The below case study, provided by a cohort trial provider, demonstrates one participant’s change in behaviour.

Case study

Roger*was referred to the cohort trial from another program. Roger’s ex-wife Nancy and daughter Belinda were engaged with the other program. Nancy reported that during their relationship Roger would be derogatory towards her, stating she was “useless” with money and criticised her for the housework and her parenting. Roger also had a history of restricting Nancy’s access to money during their relationship and was now withholding child support post-separation. Roger had refused to contribute to rent payments following their separation. The reported incident which led to the IVO was when Roger made a threat to his wife to “watch your back”.

During the initial cohort trial meeting with Roger, it was apparent that he had very limited insight into his behaviour. Roger was blaming Nancy and did not demonstrate accountability for his behaviour. He also did not demonstrate that he understood the impact that his behaviour had on Belinda. Roger advised that he understood the purpose of the program, but was unsure why he would be referred given he did not believe he was abusive in any way. Despite Roger being dismissive of his behaviour, he agreed to continue to attend sessions. The sessions focused on concepts of being a father, roles within the family, family violence behaviours, making positive parenting choices and goal setting. Roger struggled to keep a focus on Belinda and would frequently try to divert the topic of discussion.

During the program, there was a noticeable shift in Roger’s behaviour. Roger described that his communication with Nancy was now “friendly for Belinda’s sake” and that he was making a conscious effort to speak more positively about Nancy when Belinda was present. Roger was pleased that he has now been able to ensure his focus remains on strengthening his relationship with his daughter.

Nancy also provided feedback that she was pleasantly surprised at the improvement in Roger’s communication with her. Nancy was pleased that recently Roger had agreed to change access arrangements during the school holidays to ensure Belinda was able to take a holiday to Queensland with Nancy. Also Roger had paid all the required child support and had also paid for Belinda’s school jumpers and Scout camp. Nancy also said “He seems to be making a genuine effort with his daughter”.

The cohort trial also spoke with Belinda who provided positive feedback. Belinda was very excited to talk about the rice and vegetable dish that her father had cooked for her over the weekend. Belinda also said “My dad was struggling a lot before, he used to yell at my mum a lot, he would say bad things about my mum all the time, well that was until you came along”.

*Names have been changed

6.4.1 Strategies for lasting change

Being able to achieve lasting behaviour change is pivotal to the long-term success of the cohort trials and case management.

Participants acknowledged that they would need to continue to work on implementing these strategies in order for them to become ‘learned behaviours’, and this particular perpetrator intervention program was a single step in what was a long-term process.

You learn something and it's like riding a bike, you don't forget it and it's always in the back of your head. You cannot do that for six years, but it's going to come back to you. It's something that's always there.

I’ve had to do also my own work outside of the program…. The program gives me the ingredients and then I go home and put it all into action.

Whilst some participants expressed confidence that they would be able to maintain progress even upon conclusion of their intervention, others expressed concern over the long-lasting impact of perpetrator intervention programs on behaviour change outcomes. This reinforces that these programs represent one intervention over a finite time period, when the process for behaviour change can be long and require multiple interventions over an extended period of time. This perspective was reinforced by accounts from people who experience violence, who expressed uncertainty about the lasting impact of behaviour change.

He knows he can't get away with anything while the program's there. And yes, I'm hoping it stays that way but you don't know, do you?

I'm worried about what’s going to happen when the program finishes, because he's going to go back to not really having any support… We’ve got to get through all of that relatively unsupported, I guess. So that's what worries me.

6.4.1.1.1 Readiness to complete program

Whilst some participants stated they accessed other formal supports such as drug and alcohol support, or counselling, or telephone referral services which would continue to be available to them outside the perpetrator intervention program, there was limited evidence that people who use violence had concrete support networks established to transition into post-completion.

Whilst the program end date was clearer for cohort trial participants, and there was therefore greater structure around exit planning, a number of the case management participants indicated that they were in need of ongoing support. Similarly, a number of participants indicated they have developed a reliance on, or attachment to their case worker. Most indicated that they would like to see their case worker for as long as possible, and some were of the belief that they would be able to contact their case worker indefinitely, despite the program only being funded for 20 hours per participant. This places an additional burden on case workers, who in many cases already have significant client caseloads.

I don't think you can put a timeline on it, to be honest. I don't think you can because – I don't think you can put a timeline on it because I grew up with what I've just dished out so in order to me to – I've crossed the line. So I need to keep doing refreshers, so I don't get complacent and fall back into a hole. I believe I need to do this for the rest of my life.

I don’t think there’s anything other than that. I mean otherwise if I will need anything, which I don’t think I will, I will still ask for a hand, because I’ve got a contact for [Case Worker]… I feel free to go back to them at any time.

I would be happy to see [Case Worker] for the rest of my life, you know, to talk about all those things. I don’t feel like stopping it, let’s continue it.

Similarly, people who experienced violence were unclear as to how long they would be receiving support from the family safety contact worker. One person reported that their support had ended, but they had not been informed by the provider. This participant stated they were not made aware until they had tried to contact the provider.

I called her a month or couple months ago and then she just told me that they closed but they didn’t actually tell me they were closing or send me a letter… the closure process was not great. I was quite surprised… it was disappointing.

There are some providers who indicated they have a process of notifying the person who experiences violence when the engagement with the person who uses violence is ending. They then provide support as needed to the person who experiences violence, for periods of up to six months in some cases.

Across the board, however, there is the need for improved communication and planning regarding the end of support process. Participants should be made aware of other avenues for support, and the protocols for continued contact with the case worker. Particularly as there are instances where program staff are feeling overburdened by the intensity of the support they are providing to participants, it is important that there is exit planning to reduce the ongoing reliance on case workers.

However, this also demonstrates that the short-term nature of the program is often at odds with the long-term process for changing behaviour. Recognising that behaviour change can be a process which takes many years, it is unreasonable to expect that the individuals involved in these programs will not need further support to maintain and build on their progress beyond a 10-20 week program. Some participants expressed the need for ‘refresher’ courses or follow-up sessions once the program finished.

Yes, it was too brief. And I voiced that concern to [Facilitator 1] when we were finishing off the Men’s Behaviour Change program they were talking about things saying, 'How has it helped you, and how do you think you can do this and implement it, do you think you can implement it?' And I said, 'No, I know myself and I’ll probably need reminders.' And that was one of the reasons that I ended up seeing a counsellor after the course finished.

It’s like learning to drive a car then all of a sudden you’re on your P plates and you’re driving by yourself. It’s a different feeling then. Where you’ve got that support when you’ve got somebody next to you. And that’s what I felt with the course. I think the course was really good. And I just think that it should have something that has the follow-ups where you can go and continue on.

6.5 Outcomes for people who experience violence

6.5.1 Risk management

Despite the limited timeframes for which to measure notable changes in participant behaviour, providers have commented on the value of the programs in allowing for a greater level of oversight and risk management of these individuals. Particularly for people with complex needs, by engaging them in service provision and case management, this is an effective mechanism for keeping them in view.

This is particularly important in the context of the introduction of the multi-agency risk assessment framework (MARAM). Whilst the practice guide is currently focussed on victims, the information sharing and knowledge of the risk presented by the perpetrator, from the case manager’s perspective, is a vital component of this process. This adds to providing a more comprehensive picture of the risk presented to the victim, in order to increase their safety. When a person who uses violence disengages from service provision, this risk can increase.

6.5.2 Reduced isolation and improved understanding of family violence

Whilst some challenges affecting the uptake of family safety contact support have been outlined in Chapter 4, there were instances where people who experience violence reported positive effects of engagement with this support.

Most people who experience violence reported that the support they received had helped them to feel less isolated. They highlighted that involvement in the program had assisted them to realise that they were not alone in what they were experiencing. Some participants stated that discussions with the family safety contact worker had helped them to see that they were not going ‘crazy’ or ‘insane’, but that their reaction to the violence they experienced was normal.

Having a person available to listen to their story was an important contributor to this positive experience, as it allowed them to feel understood.

[Case Worker]’s really given me the confidence to know that what I’m doing matters and what I’m doing is right. And what he’s doing was wrong.

I was so used to have this fight or flight mode in me… She explained all of that. And it made you realise that you weren’t crazy. It was just normal. And that anyone who’d been in our situation would be dealing with it the same way.

But [provider] set my mind at rest, made me feel like I wasn’t going insane. That what I had been through was not normal but understandable…

This increased understanding of their experience also led some people who experience violence to acknowledge that the violence being perpetrated against them was not their fault, and that it is the person who uses violence who should be taking responsibility for their behaviour.

Yes, it’s kind of hard sometimes to not blame yourself because you shouldn’t have allowed it to happen. But yes, she always implemented to me, remember this is not your doing, it’s his doing. This is him doing it, not you doing it. And she said to me, don’t go thinking that this is your fault, because it’s not, it’s him. It’s him doing it, not you. And she said you’ve done everything you possibly can to protect those kids and yourself. And I just said to her, that’s thanks to you, because I wouldn’t have known otherwise. Like sometimes it does go through me head that, could I have done something different? But I know that it’s nothing I could have done different. He’s got to change not me. And the kids, he’s got to change.

For some people who experience violence, the program has helped them to learn that their situation is in fact one where family violence is being perpetrated. This was particularly the case for people who experience violence who come from a cultural background where these behaviours may be more accepted or tolerated. This realisation allowed these women to feel a greater level of empowerment, and seek support to improve their situation.

It was a wakeup call to me. Not to accept it. That it shouldn’t happen. Because I didn’t think it was domestic violence and they said yes, it is. And I had no idea that the screaming and yelling were domestic violence.

Yeah, and like is it the all culture, is it all the times is the lady should be so work in the home. Is it the men is came from the work and just sit in the couch and the lady should be do everything and the ladies told me in the Australia then [inaudible] yeah, I know he is a work, you are in the home, but they told he's at work, you look after children and you have a lot of shopping, you have a lot of do it, lot of job as well. When he is a come in the home, if he needed something, if you are busy, he can do that by himself as well. Yeah.

6.5.3 Feelings of safety

A number of people who experience violence indicated that their feelings of safety had improved as a result of the family safety contact function. Some felt that this was because they had a point of contact if they were to ever feel unsafe. Others noted that they felt reassured that the person who used violence was in a behaviour change program.

It's more the safety part of it. Telling me what I can do, what – and I know they're there and I know they're a phone call away, I can ring them. That's what I like about it as well. And you feel safer and the kids feel safer because of that. (Person who experiences violence, Cohort Trial)

I definitely do feel safer. I know what to look for. I keep my eyes open. And I feel stronger to actually stand up… to him. To have the strength in myself to go, okay, you can do this. You can get past this and nothing is going to stop you from living the life that you deserve. Not just the one that was on offer. (Person who experiences violence, Case Management)

The below case study provided by a cohort trial provider demonstrates the involvement in the cohort trial of a person who experienced violence, after previously being misidentified as the primary aggressor.

Case study

Miranda is a cisgender, lesbian woman in her late twenties. Miranda was arrested and charged after an incident in which Miranda smashed some of her girlfriend Emma’s property at the home that they shared. As well as criminal charges, this incident resulted in an IVO which obliged Miranda to leave the home, making her homeless.

Miranda was referred to the cohort trial by her criminal defence lawyer who believed that Miranda’s participation in this cohort trial would reflect well on her, and indicate to the magistrate that Miranda was engaged in taking responsibility for the impact of her behaviour.

On entering the cohort trial, Miranda and Emma were engaged as part of the Integrated Service Response model, with separate therapeutic family violence specialists working with each, overseen by the senior practitioner. Miranda expressed high levels of shame and remorse about her behaviour, and anxiety and suicidal ideation.

Through a rigorous assessment process, it became clear that the long-term dynamic of Miranda’s relationship with Emma was one in which Emma used aggression, intimidation, threats and emotional abuse to achieve coercive control over Miranda’s life. Like many victim/survivors of abuse, Miranda had for a long time blamed herself for the abuse she experienced, and had very low self-esteem. Miranda’s arrest and criminal charges, including her interactions with police, her lawyer and the Magistrate, compounded her feelings of self-blame and shame, and encouraged her to see herself as the problem.

Due to a high number of cases like Miranda’s, where a person who experiences violence had been misidentified by their community or the criminal justice system as a person who uses violence, the cohort trial facilitators created a separate group program for people who had used forceful resistance (including physical aggression) against an abusive partner. This group became an invaluable space for mutual support and healing. Emma, who was not yet in a pre-contemplative stage of change, was supported by her practitioner in individual work only.

A vital early stage in the work with Miranda was supporting her to believe that she was someone who deserved to be supported at all. Concurrently, Miranda’s individual case worker supported her with intensive family violence case management. Difficulties with securing housing ultimately drove Miranda to move back in with Emma for a period, during which Miranda’s support worker provided her with intensive, daily support with safety planning, risk management and negotiation. Because Emma was still engaged in individual support with another cohort trial facilitator, the senior facilitator was able to monitor safety through the two facilitators.

Working closely with Miranda, her worker was able to advocate for her to be returned to the social housing register, a process which required agreement from both Emma and from the Department of Health and Human Services. Throughout this period, Miranda was provided with individualised therapeutic support, largely over the phone, focussed on understanding intimate partner violence, recognising warning signs, negotiation, fairness and responsibility.

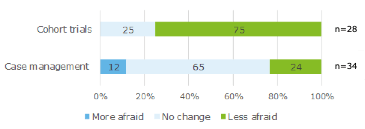

The data collection tool asked for a self-assessment of the safety of people who experience violence who are engaged in the survey, both at entry and exit from the program. Although it should be noted that data was only collected for a small cohort of people who experience violence, the results indicated that the programs are having a positive effect. This effect was most notable for the cohort trials. Chart 6.3 shows the change in responses between entry and exit. Seventy-five per cent of people who experience violence in the cohort trials indicated an increase in their feeling of safety.

Chart 6.3: People who experience violence – change in feelings of safety between entry and exit

6.6 Limitations of client achievement observations

Despite many participants describing that perpetrator intervention had helped them undergo positive changes, it was evident through discussions that some participants continued to engage in victim blaming, minimising, and denial of abuse. This does not mean participants were not genuine in noting positive outcomes, but instead, highlights the complexity of achieving behaviour change over a short period of time.

Furthermore, both people who use violence and people who experience violence felt that perpetrator intervention was unlikely to be effective for those participants who did not recognise a need to change their behavior, as previously discussed.

I think having programs available is good. I don’t think they’re successful with a certain body of male, people with personality disorders and that sort of thing, like a narcissistic or sociopathic or a borderline, because if people don’t want to change, they’re not going to change. They’ll go because it’s a means to an end for them.

There is evidence to suggest that a number of people who use violence still see themselves as the victim. Some participants emphasised that men were blamed for family violence and that they were not adequately supported compared to women. These participants often talked of services being ‘against’ them.

A unique element of the cohort trials involved recognising the intersection between past trauma and current violent behaviour. Although this was reported by participants to be beneficial, in some instances participants appeared to make reference to their past trauma as a means of distancing themselves from taking responsibility. This highlights the fine balance between recognising comorbid barriers and addressing accountability.

I didn’t believe that I used force against other people and now after doing this course, I realised that I do use force and it’s not specifically my fault why I do use force. It’s also understanding my background and how I was raised and the whole development of it as to why I now use family violence.

Unfortunately, a lot of the people who go into the program have had something used against them… yeah, they make one mistake now and they say, oh, yeah, but they did this 30 years ago so they still must be a bad bloke.

Other negative attitudes were observed when participants reflected on past incidents of violence they had perpetrated. Some participants minimised the seriousness of these incidents or denied that violence had occurred. A common rationalisation used by participants was that they had not been ‘physically violent’ to their partner.

In the end it resulted in a physically violent situation. The short story is I threw a stand that my wife and I were putting together and it hit her, and I didn’t even know it hit her. Not that that’s a justification or an excuse it’s just a fact.

We didn’t get along as well in the long run, because she was very demanding and manipulative with what she wanted. And that just led to constant arguing and abuse and I just always found myself reacting to everything. And she was just completely relentless and making me live a very limited life.

There were also instances where people who use violence engaged in a narrative of victim blaming. This involved rationalising their behaviour by claiming that the victim had ‘asked for it’ or deserved it.

But with [Son’s name], there were times when, oh – I could say years ago, when I had smacked him, that he just didn’t seem to want to learn. Or he – I tried not to – smacking was not my go to, or wasn’t my go-to feeling with his shenanigans. That was only the very last straw. But admittedly I would yell, I would scream.

There were other guys who felt that they were victims, and yet, they were clear abusers. And there were some guys who were there who sort of felt, well, she made me do it. If she hadn’t have made me do it, it wouldn’t have happened.

Drawing on the perspective of the person who experiences violence is often the most reliable indication of whether their partner or ex-partner is demonstrating change. This is because where people who use violence have not taken accountability for their actions, they may not recognise or reveal violent behaviour. They may also inaccurately report positive change in order to demonstrate progress. On the other hand, people who experience violence can provide a more complete picture.

Compared to the feedback given by people who used violence, most people who experienced violence were more cautious in expressing that perpetrator intervention had resulted in any changes. Whilst some people who experience violence noted there had been a certain level of improvement, such as increased communication, they noted there was still ‘a long way to go’ to achieve ongoing change.

There's a lot more work to be done but I can see the changes and he knows the consequences of his actions now, whereas before he didn't.

Furthermore, some participants indicated that they had observed minimal change in the person who had used violence, expressing that it would be very difficult to change their attitudes or behaviour.

I think he will continue to do what he’s doing. I don’t think he’ll ever change, and I don’t think he’ll ever see that there is a need for him to change.

Of concern, some people who experienced violence reported that the people who use violence could apply learnings from perpetrator intervention to become more manipulative and better at hiding their violence.

His awareness of family violence may have changed. He may be a bit more aware of what is family violence, but that has just made him more cunning with how he then uses it to control because if he’s aware that you can’t blackmail and stalk and do all of those things, then he’ll probably just be a bit more covert.

This demonstrates the importance of risk assessment processes, which include the victim perspective, as well as ensuring that program staff and case workers are trained in recognising and responding to collusive behaviour.

[1] Where the person could not be asked in person, the provider used their own judgement.

[2] Refer to limitations of the data collection tool in Chapter 2

[3] There were 20 ‘yes’ responses, 93 ‘no’ responses, and 46 blank or N/A responses

[4] There were 80 ‘yes’ responses, 282 ‘no’ responses, and 348 blank or N/A responses

Updated