- Published by:

- Department of Families, Fairness and Housing

- Date:

- 19 Dec 2019

Evaluation of new community-based perpetrator interventions and case management trials

Executive summary

Introduction

The Royal Commission into Family Violence (the Royal Commission) found that existing interventions for perpetrators of family violence in Victoria were not sufficiently broad nor diverse. Apart from a small number of programs for some minority cohorts, there was limited diversity in interventions for perpetrators of family violence.

In response to Recommendation 87 of the Royal Commission, two trial programs were developed; perpetrator case management and seven community-based perpetrator intervention trials targeting specific cohorts (cohort trials).

This evaluation was led by Deloitte Access Economics, and undertaken with the Social Research Centre. The evaluation objectives were to determine whether the funded activities:

- were implemented according to plan

- achieved their stated objectives

- met the needs of the target cohort and victim/survivors to a greater extent than existing programs

- presented a more effective service response.

Justification and appropriateness

The Royal Commission identified that mainstream Men’s Behaviour Change Programs (MBCPs) are not easily accessible or are not relevant for a number of people who use violence. It also found that existing, group based MBCPs are, by their nature, not designed to work with participants individually, to provide a more intensive service where necessary.

The models employed by the cohort trials have been designed or adapted to address the specific needs of these different cohorts, often drawing on approaches used overseas as they address gaps in the mainstream service delivery models typically used in Australia.

Case management provides individualised and timely responses to perpetrators. It addresses and coordinates service delivery according to the complex needs of the perpetrator (e.g. alcohol and other drug (AOD) misuse, mental/physical health concerns, gambling or homelessness). Case management has now been funded on an ongoing basis.

In the request for submissions process for the cohort trials, no trials were funded specifically addressing mental health and AOD issues due to the lack of suitable submissions targeting these cohorts.

Lessons from practice

This evaluation has determined six key features that have been observed in the current practices of the providers delivering the new cohort trials and case management. These features align with evidence of specific approaches that better enable previously excluded or under-serviced groups to benefit from government funded perpetrator interventions, such as trauma-informed practices, integrated response models, and cultural healing:

- Creating trusting relationships between participants and facilitators, and among group members to encourage engagement and participation.

- Utilising both individual and group work in a complementary manner.

- Addressing accountability with a trauma informed approach to address the underlying factors contributing to violent behaviour.

- Facilitating a holistic, wrap-around approach to address contextual factors in a person’s life by connecting them to the broader service system.

- Allowing flexibility in approach for people with different levels of need and at varying stages of change.

- Providing support to people who experience violence via a family safety contact.

Approaches for specific cohorts

While there are overarching design features that contribute to good practice, there are also specific features of program design that are appropriate for particular cohorts.

For Aboriginal cohorts, cultural healing and connection to culture and country is necessary, so they are able to first address their own healing from past trauma and grief, in order to subsequently address their use of violence. Engagement with Elders, sufficient time to deliver and implement the programs, meaningful partnerships and Aboriginal self-determination in design and delivery are important.

There are some parallels for the LGBTI and women who use force cohorts in terms of enabling participants to heal from violence/trauma and the use of peer support.

The program for culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) participants delivered the program in a culturally appropriate manner, including applying a cultural lens to mainstream materials, and having facilitators who belonged to the two cultural groups.

For people with cognitive impairment, the program is a more resource-intensive version of the MBCPs. This is because the small group size, slower pace, specialist workforce and closed group are important features contributing to participant engagement (but are also more resource intensive). Using prompts and visuals has also been beneficial.

Early client achievements

Some early client achievements as a result of participating in the cohort trials and case management have been identified. Due to the short amount of time that has passed since the commencement of the programs, these findings are not definitive, however they demonstrate positive signs at this point in time.

- Providers of cohort trials and case management reported that participants have been demonstrating high levels of engagement compared with their experience facilitating mainstream programs.

- Some participants reported increased understanding of what constitutes family violence, particularly non-physical forms of violence, and how their behaviour affected others.

- There were mixed findings regarding participants taking responsibility for their behaviour, however this is to be expected given the short-term nature of the programs compared to the long-term process of behaviour change.

- Participants acknowledged that they would need to continue to work on implementing strategies in order for them to become ‘learned behaviours’. Many reflected the need for continued support beyond the life of the program.

- The programs are contributing to a greater level of risk management of people who use violence, particularly those with complex needs. By engaging people who use violence who were previously not accessing services, these programs are ‘keeping them in view’, which enables providers to better identify and manage risk.

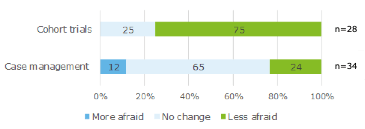

- People who experience violence reported that the support they received had helped them to feel less isolated, and a number indicated their feelings of safety had improved.

Implementation – workforce and process

The evaluation examined the activities and processes that were involved in establishing the cohort trials and case management, and made the following findings:

- Attracting staff with the appropriate skills and experience in working with people who use violence was a particular challenge for some cohort trial and case management providers. The initial 12 month funding allocation reportedly affected the ability of providers to recruit and retain the workforce.

- Referral pathways into programs from the community and justice settings needs to better understood and defined, as people who use violence traverse both systems.

- There are some challenges to effective service coordination across the sector, including a lack of capacity or willingness to work with people who use violence.

- Performance management of the programs needs to be strengthened, to ensure there is accountability and consistency for reporting on program outcomes.

Conclusion and future considerations

Overall, it has been established that the perpetrator cohort intervention trials and case management are addressing a service delivery gap for people using violence, and have contributed to delivering on Recommendation 87 of the Royal Commission. This evaluation report identifies several areas for ongoing improvement or enhancement, particularly as the programs transition from pilots to ongoing funding (case management) or providing services for an additional year (cohort trials). There are eight overarching improvement opportunities, and three that relate to cohort interventions.

- building the focus on the role of the family safety contact

- strengthening the referral pathway by raising awareness of the programs within the service system

- contributing to building workforce capability

- improving accountability, governance and reporting of the programs through FSV

- providing improved exit planning for case management participants

- providing clarity around funding

- adopting a systems approach by creating alignment with the justice perpetrator programs

- long-term research and evaluation

- tailoring implementation and reporting targets for Aboriginal cohorts (cohort specific)

- building capability within the mental health and AOD workforces to encourage the design of suitable programs for these cohorts (cohort specific)

- consider opportunities to scale the programs (cohort specific).

Deloitte Access Economics is Australia’s pre-eminent economics advisory practice and a member of Deloitte's global economics group. For more information, please visit our website: www.deloitte.com/au/deloitte-access-economics

Deloitte refers to one or more of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited (“DTTL”), its global network of member firms, and their related entities. DTTL (also referred to as “Deloitte Global”) and each of its member firms and their affiliated entities are legally separate and independent entities. DTTL does not provide services to clients. Please see www.deloitte.com/about to learn more.

Deloitte is a leading global provider of audit and assurance, consulting, financial advisory, risk advisory, tax and related services. Our network of member firms in more than 150 countries and territories serves four out of five Fortune Global 500®companies. Learn how Deloitte’s approximately 286,000 people make an impact that matters at www.deloitte.com.

Deloitte Asia Pacific

Deloitte Asia Pacific Limited is a company limited by guarantee and a member firm of DTTL. Members of Deloitte Asia Pacific Limited and their related entities provide services in Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, East Timor, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Indonesia, Japan, Laos, Malaysia, Mongolia, Myanmar, New Zealand, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Singapore, Thailand, The Marshall Islands, The Northern Mariana Islands, The People’s Republic of China (incl. Hong Kong SAR and Macau SAR), The Philippines and Vietnam, in each of which operations are conducted by separate and independent legal entities.

Deloitte Australia

In Australia, the Deloitte Network member is the Australian partnership of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu. As one of Australia’s leading professional services firms. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu and its affiliates provide audit, tax, consulting, and financial advisory services through approximately 8000 people across the country. Focused on the creation of value and growth, and known as an employer of choice for innovative human resources programs, we are dedicated to helping our clients and our people excel. For more information, please visit our website at https://www2.deloitte.com/au/en.html.

Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation.

Member of Deloitte Asia Pacific Limited and the Deloitte Network.

© 2019 Deloitte Access Economics. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu.

Introduction

1.1 Program purpose

Family Safety Victoria (FSV) has established two new trial programs for perpetrators of family violence, which address the needs of a more diverse range of perpetrators, and are better integrated into the wider response to family violence in Victoria.

1.1.1 Recommendation 87 of the Royal Commission into Family Violence

The Royal Commission into Family Violence (the Royal Commission) found that existing interventions for perpetrators of family violence were not sufficiently broad nor diverse. Apart from a small number of programs for men from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) background, Aboriginal men, and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Intersex (LGBTI) community, there was limited diversity in interventions for perpetrators of family violence. For example, the Royal Commission heard that people who misuse alcohol or other drugs, or have mental health issues, found it difficult to engage in these interventions[1]

Historically, the main intervention targeted at perpetrators in Victoria have been Men’s Behaviour Change Programs (MBCPs). MBCPs are designed to assist men to take accountability for their actions and to end their use of violence and other problematic behaviour in their relationships. They are intended to assist in facilitating the behavioural changes necessary to build healthy and respectful relationships. MBCPs include a family safety contact function, who works with the person who experiences violence to ensure they are connected to services as required and are kept safe and in sight. The Royal Commission found MBCPs to be inadequate in being able to provide tailored support to address individual needs and risks.

In March 2016 the Victorian Royal Commission released 227 recommendations to reform the state’s response to family violence. Recommendation 87 of the Commission suggests the Victorian Government “research, trial and evaluate interventions for perpetrators [within three years]”, including interventions that:

- provide individual case management where required

- deliver programs to perpetrators from diverse communities and to those with complex needs

- focus on helping perpetrators understand the effects of violence on their children and to become better fathers

- adopt practice models that build coordinated interventions, including cross-sector workforce development between the men’s behaviour change, mental health, drug and alcohol and forensic sectors” [2].

The Royal Commission found that the range of perpetrator interventions needed to be broader and better integrated within the scope of initiatives targeting family violence, creating a “web of accountability” to keep perpetrators in view and protect victims and families.

In response to this recommendation, FSV have developed two new programs; perpetrator case management and community-based perpetrator intervention trials (cohort trials).

1.1.2 Perpetrator case management

One of the new approaches to address the shortcomings of current programs is the implementation of a new case management model for perpetrators of family violence.

Case management provides individualised and timely responses to perpetrators. It addresses and coordinates service delivery according to the complex needs of the perpetrator (e.g. alcohol and drug misuse, mental/physical health concerns, gambling or homelessness). Besides ensuring perpetrators are in view of service providers and relevant authorities, case management aims to directly increase the safety of victims via a number of methods. This includes providing a platform to engage with victims through a Family safety contact, and identifying relevant information (shared under the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme) to contribute to risk assessment and management for victim safety. Case management also helps involve the perpetrator in planning and decision making to encourage engagement with other social activities and universal services.

The approach to case management consists of developing strategies and skills to stop the perpetrator’s use of violence, as well as increasing their motivation for change. Perpetrators under case management are assisted in:

- recognising abusive patterns and tactics

- seeing the relevance in their engagement with support services and long-term behaviour change, and

- taking responsibility for their violence through their engagement with support services such as MBCP [3].

Funding provides for an average of 20 hours per participant.

Case management was targeted at perpetrators who:

- have been removed from the home and require practical support;

- are deemed unsuitable for MBCPs. This could be due to:

- English not being a primary language

- having complex needs (mental health, alcohol and other drug issues (AOD), homelessness, cognitive impairment and acquired brain injury) and require support, or

- being at risk from other perpetrators.

- are attending a MBCP and require additional support to stay engaged, including those at risk to themselves, or

- require additional support after the conclusion of a MBCP [4].

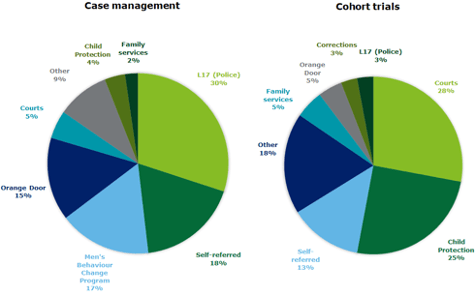

Referrals to case management occur primarily through existing intake services and Orange Door locations. This includes police referrals, the Men’s Referral Service, and informal referrals (such as Child Protection, family services, or other pathways).

The providers by area are listed in Table 1.1 below. Further detail on each provider by area, is shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Providers by DHHS area

|

DHHS Area |

Provider |

|

Bayside Peninsula |

|

|

Southern Melbourne |

|

|

North Eastern Melbourne |

|

|

Western Melbourne |

|

|

Hume Moreland |

|

|

Brimbank Melton |

|

|

Outer Eastern Melbourne |

|

|

Inner Gippsland |

|

|

Inner Eastern Melbourne |

|

|

Barwon |

|

|

Loddon |

|

|

Central Highlands |

|

|

Goulburn |

|

|

Wimmera South West |

|

|

Mallee |

|

|

Ovens Murray |

|

|

Outer Gippsland |

|

*Aboriginal Community Organisation or mainstream provider delivering dedicated Aboriginal targets

1.1.3 Cohort trials

FSV is providing funding to trial new community-based cohort trials. Under the new program design, the scope of perpetrator interventions has increased in order to target more diverse perpetrator cohorts who were not being adequately serviced by the mainstream system.

The scope of the cohort trials has been structured as follows:

- two targeted to men with cognitive impairment

- two targeted to Aboriginal (or non-Aboriginal) fathers in Aboriginal families

- one targeted to women who use force

- one targeted to cis women (heterosexual, bisexual and lesbian), transgender and gender diverse people who use violence, and

- one targeted to migrants/refugees from Hazara (Afghani) and South Asian communities.

Further detail on each trial, including the approach and location, is shown in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: New perpetrator cohort trials

|

Agency (lead and partner) |

Target of trial |

Approach |

Coverage of the trial |

|

Bethany Community Support |

Men with cognitive impairment |

MBCP |

Barwon |

|

Drummond Street |

cis women (heterosexual, bisexual and lesbian), transgender and gender diverse people who use violence |

Mix of one-to-one and group responses |

North East Melbourne |

|

Anglicare and VACCA |

Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal fathers |

Cultural healing approaches |

Bayside Peninsula |

|

Baptcare and Berry st |

Women who use force, including Aboriginal women |

Therapeutic group setting |

Central Highlands |

|

Peninsula Health |

Men with cognitive impairment and/ or learning disabilities |

Group and one-on-one interventions |

Bayside Peninsula |

|

Bendigo and District Aboriginal Co-operative |

Aboriginal fathers and non-Aboriginal fathers with Aboriginal families. |

Healing and re-storying/reflective practices in the bush setting |

Loddon |

|

InTouch Multicultural Centre Against Family Violence |

Newly arrived migrants and refugees from the Hazara (Afghani) and South Asian communities Introduction in 2019-20 of programs for African and younger men (18-20 years) |

In-language, culturally informed interventions |

Southern Melbourne |

Source: Family Safety Victoria (2018a)

Evaluation approach

2.1 Evaluation – purpose, role and scope

This evaluation is a requirement of Recommendation 87 of the Royal Commission. The evaluation findings are intended to inform and improve policy and drive system improvement, making it more responsive to the needs of our diverse Victorian community.

The evaluation was conducted by Deloitte Access Economics, with support for the qualitative research with people who experience and use violence undertaken by the Social Research Centre.

The evaluation objectives were to determine whether the funded activities:

- were implemented according to plan

- achieved their stated objectives

- met the needs of the target cohort and victim/survivors to a greater extent than existing programs

- presented a more effective service response. [1]

- the evaluation will also assist to inform future funding decisions, and therefore aligns with the lapsing program guidelines as stipulated by the Department of Treasury and Finance.

The evaluation commenced in September 2018, with the first data collection phase (process) occurring in April – June 2019, and the second data collection phase (outcome) occurring in August – October 2019. Prior to the data collection, there was an extensive period of evaluation planning, including the process of gaining ethics approval from the Australian National University Human Research Ethics Committee (ANU HREC). Evaluation of the MBCP group work element was not in scope of this evaluation.

The evaluation involved two phases:

- Interim (process) evaluation – reviewed implementation of the funded trials. This part of the evaluation considered whether the trials are being delivered at the standard and volume outlined in the service agreement, and whether they are acceptable and accessible to their target cohorts. It also considered whether the programs are achieving their desired short-term outcomes.

- End of program (impact) evaluation – assessed the extent to which the funded trials met the needs of the target cohorts and achieved their desired outcomes.

In order to inform the evaluation and key lines of enquiry, a series of evaluation questions were developed. These included both process and outcome evaluation questions. The evaluation questions considered the appropriateness, effectiveness and efficiency of the initiatives.

Table 2.1 categorises the process evaluation questions under one of the three evaluation domains (appropriateness, effectiveness, efficiency). Questions were developed based on those outlined in the Request for Proposal, the Department of Treasury and Finance’s Lapsing Program Evaluation guidelines, and advice from Deloitte Access Economics. The questions were further refined following a workshop with a selection of service providers of the trial programs held in November 2018. Questions taken from the Mandatory Requirements for Lapsing Program Evaluation document are italicised. This evaluation is not a Lapsing Program Evaluation, but does incorporate the Department of Treasury and Finance’s Lapsing Program Evaluation questions.

Table 2.1: Evaluation questions

| Evaluation domains | Evaluation questions |

|---|---|

| Process Evaluation Questions | |

| Appropriateness/Justification |

What is the evidence of continued need for the initiatives and role for government in delivering the initiatives? (P1) Have the initiatives been implemented as designed? (P2) How are the initiatives innovative and contributing to best practice? (P3) |

| Effectiveness |

Are there early positive signs of change that might be attributable to the initiatives? (P4) To what extent are the outputs being realised? (P5) Have people who use violence and people who experience violence responded positively to the program, including enrolment, attendance/retention and satisfaction? (P6) What are the barriers and enablers to effective referral of participants? (P7) What governance and partnership arrangements been established to support the implementation of the initiatives and are these appropriate? (P8) Do the program workforces have a clear idea of their roles and responsibilities? (P9) What components of the model are perceived to be the most valuable? (P10) What improvements to the service model could be made to enhance its impact? (P11) Have there been any unintended consequences, and if so, what have these been? (P12) |

| Efficiency | Has the department demonstrated efficiency in relation to the establishment and implementation of the programs? (P13) |

| Impact Evaluation Questions | |

| Appropriateness/Justification |

Are the programs responding to the identified need/problem? (I1) What are the design considerations of the program to support scalability? (I2) |

| Effectiveness |

Have the program inputs, activities and outputs led to the desired change mapped out in the program logic? (I3) To what extent have people who use violence and people who experience violence responded positively to the program, including enrolment, attendance/retention and satisfaction? (I4) What are the drivers for effective participant engagement in the programs? Does this differ according to the different cohorts? (I5) What is the impact of the program on victims/survivors’ perceptions of safety? (I6) What are the barriers and facilitators to the programs being integrated into the broader service system? (I7) What impact have the programs had on the management of risk associated with this cohort? (I8) What impact have the programs had on referral pathways and information transfer between community services and relevant authorities? (I9) What impact have the programs had on the confidence, knowledge and skill of the case management and service delivery workforces in supporting the target cohort in the community? (I10) Are key stakeholders, including the program workforces, supportive of the model? (I11) What would be the impact of ceasing the programs (for example, service impact, jobs, community) and what strategies have been identified to minimise negative impacts? (I12) |

| Efficiency |

Have the programs been delivered within its scope, budget, expected timeframe, and in line with appropriate governance and risk management practices? (I13) Does the initial funding allocated reflect the true cost required to deliver the programs? (I14) |

2.2 Indicators of program effectiveness

To address each of the evaluation questions, a series of performance indicators were identified. These are presented in Appendix A. In addition to mapping each performance indicator to an evaluation question, the measure and data source(s) required to measure each indicator is provided.

Evaluation findings are strengthened through multiple sources of evidence (i.e., triangulation and validation of results). As such, for each evaluation question, multiple performance indicators from various data sources have been collected to provide a broad range of perspectives. Where practical, both quantitative and qualitative data was used.

2.3 Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the evaluation was granted by the HREC, through three separate ethics applications:

- a low risk application, for data collection with providers, referral organisations, peak bodies and government employees.

- a high risk application, for data collection involving people who use and experience violence.

- an application for data collection involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants.

Gaining approval from the ANU HREC necessitated extensive consultation with Aboriginal stakeholders, including the Dhelk Dja Priority 5 sub-working group, who reviewed the evaluation approach and subsequent reports [2].

2.4 Data Collection

The data collection involved a mix of primary and secondary data collection, as summarised below. Further detail is provided in Appendix B.

2.4.1 Primary data sources

Primary data sources included both qualitative interviews and a data collection tool, as described below:

- Stakeholder interviews – consultations with non-clients, including individual providers, FSV and DHHS representatives, coordination and referral staff, and advisory and peak bodies.

- Client interviews – a total of 87 interviews were conducted with program participants, including both face-to-face and telephone. The sampling and recruitment approach is outlined in Appendix C.

- Service provider data collection tool – to address gaps in data availability from the Integrated Reports and Information System (IRIS) system, the data management system used by FSV/DHHS for family violence programs, data was sought directly from service providers through a data collection tool. For each program participant and victim survivor, the tool included demographic, referral and outcome information.

The limitations related to this data are discussed in Section 2.5. An evaluation readiness tool was developed to understand the data being collected by all providers to inform the preferred approach for recruiting people who use violence and people who experience violence for primary data collection, and to identify any planned or current evaluation activity being undertaken by providers.

2.4.2 Secondary data sources

There were two secondary sources of data used to inform the analysis in this report. This included:

- FSV/DHHS data – including program and provider details, e.g. program duration, anticipated caseloads, recruitment approach, internal evaluation details, brokerage data, and governance terms of reference; deidentified participant information from the DHHS IRIS case management system, and other documentation provided by service providers, such as grant applications, acquittal reports, etc.

- Literature scan – a literature scan focused on best practices in case management and interventions for perpetrators of family violence was conducted.

2.5 Limitations of the research

Limitations pertaining to sample size and composition, participant eligibility criteria, and provider data collection and analysis were encountered throughout the evaluation data collection approach. Findings presented in this report should be considered in the context of these limitations.

2.5.1 Sample size and composition

Firstly, the findings should be interpreted in the context of the overall sample composition. People who have experienced violence were difficult to engage in the research, with only 18 participants interviewed (compared to 69 people who have used violence). This presents difficulties when corroborating the feedback from people who have used violence with those who have experienced violence. This is an important limitation, as people who have experienced violence are considered to have a more objective point of view, particularly as it relates to observing any outcomes.

The qualitative research is not intended to provide a representative overview of the population, and thus, findings should not be generalised.

2.5.2 Participant eligibility and identification

Participant recruitment was guided by a set of criteria designed to uphold the safety of participants and researchers, while also ensuring minimal disruption to participant engagement in services. This reduced the pool of eligible participants to participate in the qualitative research. For example, one criteria was that people who used violence were only eligible to participate if the affected family member was engaged by a family safety contact or specialist family violence service, in order to manage any potential risk that could arise from the interviews. This criteria greatly reduced the number of available participants. This may explain the lower number of people experiencing violence participating in the interviews compared to people who use violence.

The recruitment of participants via service providers is an important mechanism for reducing and mitigating risk. In particular, it ensures couples are not both interviewed, and that service providers can ensure the safety of the person experiencing violence. It does however, introduce the potential for a biased sample. For example, providers may only have forwarded participants who they thought would reflect positively on the service, or perhaps participants who were more engaged in the service would be more likely to volunteer for the research. This potential risk was mitigated by the approaches adopted by the Social Research Centre, including provision of a ‘recruitment pack’ to providers and regular check-ins with providers regarding the process. These mitigation strategies were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee.

2.5.3 Data collection tool

There are limitations with the data received from providers via the data collection tool. Of the providers who submitted the data collection tool, many had substantial gaps in content. This was not unexpected, as the tool was a new instrument, and providers were implementing the mechanisms for data collection activity at an organisational level. Some of these limitations were rectified between phase one (data provided to the evaluators in July 2019) and phase two (data provided to the evaluators in September 2019). Additional training was provided, to emphasise the need to complete all fields (rather than leave blanks) and how to interpret particular fields such as referrals. Despite some improvement between phase one and phase two, there were still significant gaps in the data, and further work is needed to ensure data is consistently recorded by providers moving forward.

These gaps do, however, make the data unsuitable for drawing robust conclusions on program outcomes at this point in time, or being able to make any substantiated claims or comparisons at a cohort level. Particularly for the data collected on participant outcomes, there are significant gaps in exit data and equivalent data for people who experience violence, with which to make valid comparisons against the entry level data.

2.5.4 Time frame

It is recognised that changing behaviour can be a long and complex process, that can require multiple interventions. This evaluation collected data about people who used violence who had received one of the interventions within 12 months of the evaluation commencing. As a result, the evaluation was not able to capture any long-term or longitudinal data to determine the effectiveness of the programs over a longer timeframe.

[1] Request for Quote - Evaluation of new community-based perpetrator interventions and case management trials, Department of Health and Human Services

[2] While an important process, these additional activities meant that interviews with Aboriginal participants were delayed during the process phase of the evaluation. The additional consultation required to gain ethics approval for culturally diverse clients resulted in similar restrictions. As a result, these cohorts received one round of interviews over an extended period of time.

Justification & appropriateness

Key findings

- The Royal Commission provides evidence for the need for perpetrator interventions targeting specific cohorts. It identified that mainstream MBCPs are not easily accessible or are not relevant for a number of people who use violence. It also found that existing, group based MBCPs are, by their nature, not designed to work with participants individually, to provide a more intensive service where necessary.

- Currently, there is very limited knowledge of how to address certain cohorts in the context of perpetrator intervention programs.

- Responses to perpetrators need to address individual risk factors contributing to violent behaviours, such as past experiences of trauma, alcohol and drug misuse, and mental illness.

- The models employed by the pilot programs have been designed or adapted to address the specific needs of these cohorts.

- A specific program for people with mental health and AOD issues is not currently being provided, despite this being an identified need. Since the programs were established, FSV has been involved in capacity building activities in order to strengthen this response across the sector.

Perpetrator intervention programs are a common response for addressing the behaviours associated with family violence, and to bring perpetrators into view. These programs offer a preventative approach to behaviour change, alongside other more punitive responses such as intervention orders or criminal justice responses[1] . These programs are designed to treat the underlying beliefs, assumptions, or thought patterns that drive or facilitate the use of violence against their partner and/or children.

MBCPs have been developed and in use since the 1980s, in Australia and internationally, however service gaps still exist as they are either significantly less effective for certain cohorts, or minority cohorts are excluded from participation in MBCPs altogether. The Royal Commission found that interventions needed to respond to perpetrators and promote behaviour change vary. Some individuals require support through a behaviour change program, while others require tailored and intensive assistance [2]. This literature scan discusses the types of perpetrator intervention models that exist currently, their limitations, and how the new cohort trials and case management are designed to better treat certain cohorts of perpetrators.

3.1 The identified problem

The Royal Commission highlighted the importance of “bringing perpetrators into view and assisting them to change behaviours” for reducing family violence. The Royal Commission found that the response to perpetrators was under-developed, despite initiatives that aimed to maintain surveillance of high-risk perpetrators. Further, it cited analysis that recidivism from a small number of perpetrators account for a comparatively large share of family violence[3]. While it highlighted there were programs for perpetrators, there existed significant service gaps.

The Royal Commission heard that mainstream MBCPs are unsuitable for a number of perpetrators because they are (a) not easily accessible, e.g. there are language or cognitive barriers, or (b) they are not relevant, e.g. they do not address differences in cultural context, gender or sexuality. The Royal Commission also found that existing, group based MBCPs are, by their nature, not designed to work with participants individually, to provide a more intensive service where necessary. Additionally, a lack of understanding of family violence within these diverse communities can mean that individuals do not actively seek help, or when they do, providers are not equipped to respond effectively. Reasons for this include:

- the need to comply with minimum standards that mean course content is not suitable for certain people due to language, cultural, religious or sexuality reasons

- there is a lack of qualified staff trained in working with these cohorts of men

- there is limited capacity to provide a more intensive service where necessary.

As outlined in the Royal Commission final report, while there may be common risk factors for family violence, perpetrators are a diverse group. In addition to the barriers above, there are also specific needs and experiences relevant to different groups which impact on their ability to access and engage in mainstream MBCPs. Section 3.1.1 outlines the target populations which were identified by the Royal Commission as being typically excluded from mainstream programs, and the specific barriers they face.

3.1.1 The needs of specific cohorts

Given the limitations in the current service approach, it is important to understand the context of certain minority groups, as identified by the Royal Commission, which should inform program design.

3.1.1.1 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [4] who use violence

Aboriginal culture and identity has existed and survived for more than 60,000 years in spite of the impact of colonisation and tide of history. Within the State of Victoria, Aboriginal cultures and communities are not homogeneous but diverse entities, each with rich and varied histories and cultural heritage.

However, since colonisation, Aboriginal people have experienced violence by non-Aboriginal people, particularly during the early settlement period between the 1830s and 1900s. This violence has been both physical, structural and institutional. In addition to many documented instances of frontier violence, it includes but is not limited to dispossession of land and children, exclusionary policies, prohibition to practicing culture and language, removal from their ancestral country, relocation to missions and genocide. A greater proportion of Aboriginal people are impacted by the Stolen Generation in Victoria relative to other jurisdictions [5]. Such violence has led to the accumulation of intergenerational trauma, which impacts experiences of family violence within Aboriginal communities [6].

Family violence is defined by the Victorian Indigenous Family Violence Task Force[7] as:

an issue focused around a wide range of physical, emotional, sexual, social, spiritual, cultural, psychological and economic abuses that occur within families, intimate relationships, extended families, kinship networks and communities. It extends to one-on-one fighting, abuse of Indigenous community workers as well as self-harm, injury and suicide.

This definition of family violence is used in Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families, released in November 2018. This is an Aboriginal-led Victorian Agreement that commits signatories to work together to ensure Aboriginal people, families and communities are living free and safe from family violence. Dhelk Dja recognises that family violence is not part of Aboriginal culture or ever was before settlement occured. Family violence against Aboriginal people can be perpetrated by Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people.

In the case of programs for Aboriginal men, there are different causes of family violence in these communities, which stem from the impact of colonisation, and the loss of culture, connection to Country and kinship relations[8]. Responses to family violence for Aboriginal people and families need to be Aboriginal-led, take a holistic approach (emotional, spiritual, and cultural wellbeing), and understand cultural and historical dynamics. It is important for non-Aboriginal organisations to involve Aboriginal organisations in service design and delivery.

The Royal Commission highlighted the lack of culturally safe, holistic and therapeutic interventions for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men. VACSAL’s submission to the Royal Commission noted that nine out of 10 Aboriginal men who access mainstream behaviour change programs delivered by non-Aboriginal providers say they are not appropriate for Aboriginal men [9].

3.1.1.2 Culturally and linguistically diverse communities

Research and evidence from practice has showed that current (mainstream) programs do not adequately address the nature and causes of intimate partner violence perpetrated by men from culturally and ligusitically diverse backgrounds. In general, MBCPs are largely based on western notions of family and family life [10]. Additionally, for men lacking proficiency in the language the program is offered, understanding of the content is often limited, and therefore participation will not be meaningful. Evidence presented to the Royal Commission found that of 35 MBCPs, only two were delivered in languages other than English [11].

In addition to the language barriers, there is a lack of culturally appropriate practice within existing service models. While there are a very small number of culturally specific programs, most programs do not draw on the cultural norms and beliefs of men from CALD backgrounds. Of those that do, there are often long waitlists, and many participants have to travel long distances to attend the programs. Additionally, there are a limited number of facilitators trained to work with people who use violence from culturally diverse backgrounds [12].

3.1.1.3 Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people

Mainstream perpetrator interventions models, such as Duluth or Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) approaches typically do not consider the specific needs or unique circumstances of LGBTI couples [13]. Research suggests LGBTI people experience unique stressors that accompanies being part of a sexual minority population [14]. These can be internal stressors, such as internalised homophobia, or external, such as actual experiences of violence, discrimination and isolation.

The focus of mainstream MBCPs has typically been focused on responding to male violence against women. This reflects the gendered and binary nature of family violence, but excludes affected LGBTI people. No to Violence conducted a study in 2015 which showed that male same sex intimate partner violence is significantly under-reported, and there are cases where generalist services may minimise violence between two people of the same gender[15]. The Royal Commission also found that there are circumstances where it can be unsafe for LGBTI people to attend these programs, as other members of the group may be homophobic or transphobic/biphobic and they exclude women.

3.1.1.4 Women who use force

Examination of literature regarding MBCPs shows that the overwhelming focus of these programs is on men, as the name suggests, as men account for the significant proportion of people who use violence. However, there are a cohort of women who use force in intimate relationships, often as a form of resistance against other adult family members. Although there are women who are predominant aggressors in domestic violence situations, researchers agree that most women who use force in their intimate relationships are victims who self-defended or retaliated [16]. At the time of the Royal Commission, there were limited suitable services in Victoria to provide an intervention for this group of women to address their violent behaviour.

3.1.1.5 People in rural, regional and remote communities

The Royal Commission heard that there are limited perpetrator intervention programs for people in rural, regional, or remote areas. Where these programs do exist, there are lengthy waitlists, and sometimes people access non-specialised counsellors as an alternative.

3.1.1.6 People with disabilities who use violence

People with disabilities, such as intellectual disabilities or acquired brain injuries, often struggle to comprehend course content, have limited capacity to engage in a group context, or are screened out of mainstream MBCPs altogether.

There is very limited practice guidance to support engagement with people with a cognitive impairment in MBCPs or other perpetrator interventions. A report undertaken by the Commonwealth Department of Social Services to scope innovative perpetrator intervention practices in Australia found that there is very little available for this cohort. The report states:

FDV [Family and Domestic Violence] perpetrators with cognitive impairments – mild intellectual disability, moderate intellectual disability, ABI and foetal alcohol syndrome – appear to be poorly served by existing interventions. It is reasonable to expect they would have specific needs; but no jurisdiction seems to have policy or documented pathways to indicate where and how interventions might take place [17] .

3.1.1.7 Older people who use violence

Whilst there are no barriers to the referrals or access of older men in mainstream MBCPs, they may have difficulty engaging with the content due to health issues, e.g. dementia, and other behavioural or cognitive issues.

The dynamics of elder abuse may also differ from other instances of family violence, due to the presence of both gendered and ageist attitudes. This may require alternative approaches to changing attitudes and behaviours.

3.1.1.8 People with complex needs, including mental health and AOD issues

In their submission to the Royal Commission, the Centre for Forensic Behavioural Science at Swinburne University included the following statement[18]:

“Intervention programs need to be responsive to the complex needs of the wide variety of family violence offenders. In particular, we must improve provision of specialist interventions to those with complex and serious mental, personality, and substance use disorders. There is a clear need for better integration and communication between mental health services, drug and alcohol services, and offence-specific program providers”.

The most common risk factors put to the Royal Commission which described people who use violence with complex needs were mental illness and AOD abuse. The Royal Commission heard that the mental health and AOD sectors remain disconnected from family violence services, and people with these conditions are less likely to engage with services or follow up on referrals. Additionally, when someone has a mental illness or AOD issues, they are unlikely to be able to engage in other services until these problems are addressed[19]. The Royal Commission also heard that there is a lack of capacity among current program facilitators to adequately identify and address mental health and AOD issues, which includes a lack of resources across the sector to provide individualised, tailored responses [20].

3.1.2 The proposed response

The Royal Commission recommended that perpetrator interventions targeted at these specific cohorts be established, as an alternative to mainstream MBCPs. The generalist response has been described as inflexible and outdated, and not keeping pace with best practice [21].

Programs offering cohort specific, culturally sensitive approaoches were suggested, as generalist programs may be perceived as alienating or irrelevent to the circumstances of specific cultural groups [22]. Additionally, responses to perpetrators needed to address individual risk factors contributing to violent behaviours, such as past experiences of trauma, alcohol and drug misuse, and mental illness.

Recommendation 87 of the Royal Commission stated:

The Victorian Government, subject to advice from the recommended expert advisory committee and relevant ANROWS (Australia’s National Organisation for Women’s Safety) research, trial and evaluate interventions for perpetrators that:

- provide individual case management where required

- deliver programs to perpetrators from diverse communities and to those with complex needs

- focus on helping perpetrators understand the effects of violence on their children and to become better fathers

- adopt practice models that build coordinated interventions, including cross-sector workforce development between the men’s behaviour change, mental health, drug and alcohol and forensic sectors.

3.2 Existing frameworks for perpetrator intervention

Most men’s behaviour change programs share common theoretical frameworks which underpin the treatment approaches. The most dominant theoretical model is known as the Duluth model, followed by cognitive behavioural therapy. These approaches are designed to address the underlying issues and causes of violent behaviour. However, it should be noted that few MBCPs only apply a single theoretical model to their approach. Most program providers blend two or more models within their program design.

3.2.1 The Duluth model

The Duluth model uses a feminist analysis of partner violence. Designed to educate and raise awareness, under this model intimate partner violence is treated as a response to the patriarchal nature of social arrangements [23]. Treatment of the perpetrator is based on coordinated strategies grounded in the experience of the victim, as opposed to the program being based solely on a criminal justice response.

The Duluth model incorporates the following approaches:

- highlighting perpetrator accountability by taking the blame off the victim

- prioritising the victim ‘voice’ and experiences in the creation of policies

- actively working to change societal conditions that support men’s use of control over women

- incorporating behaviour-change opportunities within court-ordered mechanisms

- collaborating across criminal, civil and community agencies to improve the community’s response to family violence [24]

Central to this approach is the Power and Control Wheel, which emphasises that abuse and violence is linked to male power and control, and the accompanying aspects, or ‘spokes’ of this wheel [25] include:

- minimising

- denying

- blaming

- using intimidation

- emotional abuse

- isolation

- children

- male privilege

- economic abuse

- threats.

This framework recognises that males use other means, in addition to physical acts of violence, to maintain control. Different methods are applied within the model to explore how men use controlling behaviour in relation to different themes. That men tend to view themselves as the victim, and that violence is used to regain power, status or respect (often from other areas of their lives), is also highlighted.

Another related model commonly used in Australia is the Risks Needs and Responsivity (RNR) model. This model takes a more individualised approach. Factors such as individual criminal history, learning style, and actuarial risk and instability factors are considered in addition to the socio-political factors emphasised in the Duluth model [26].

The Duluth model’s success has been attributed to inter-agency cooperation, and the fact that the model is developed from women’s own experiences of violence (incorporated within the spokes of the power and control wheel).

There has been some criticism directed at the Duluth model for being a “one-size-fits-all” approach, as it focuses on structural factors - gender based power relations - as the primary cause of domestic violence[27]. Dutton and Corvo [28] denounce the model as an ideologically narrow model of intervention, calling it a “radical form of feminism”. They also criticise the Duluth model for not being therapeutic, shaming clients, and showing no effective outcomes, and call for more attention to women’s violence. Gondolf [29] rejects this perspective, claiming that this narrative is misleading and can damage important progress in the field of perpetrator intervention. Gondolf highlights a multi-site, longitudinal evaluation of a Duluth-based ‘batterer intervention’, which demonstrated a clear de-escalation of abuse overtime, with 80 per cent of the men not being violent towards their partners in the previous year, at 30 months from program intake. The results also demonstrated positive impressions of change from the women’s perspective. This evaluation considered the ‘holistic’ intervention – from the arrest, court mandated referrals, supervision, and the program itself – which demonstrated that the criminal justice intervention, combined with the behaviour-change program, is not detrimental to a majority of men.

3.2.2 Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

CBT, the most common psychotherapeutic approach, is another major approach to treating perpetrators. CBT is based on the identification and correction of mental processes that grant offenders the permission to commit violence, generally in a cyclical process. Men who perpetrate violence often consider themselves victims, blaming their partner for their own violence. The goal of CBT is to interrupt this process, helping the man to identify the preceding physical signs, thoughts and feelings by which he grants himself permission to commit violence [30].

There may also be certain beliefs or thought patterns about their partner, or women in general, at the core of their behaviour that CBT explores. Vignettes, role playing, discussions, practising alternative behaviour, and teaching and rehearsing new skills are all used in the delivery of programs that incorporate CBT[31].

CBT is more of an additional as opposed to a stand-alone approach, given that the ability to apply these skills in the particular context (their relationships) is needed. The combination of feminist analysis with CBT is often used; with 68% of states in the USA taking this approach, while only 5% of states use CBT but do not incorporate power and control [32].

3.2.3 The transtheoretical model (TTM) and the stages of change

The TTM is based on the concept that people go through stages of change before they are able to successfully achieve and maintain behaviour. These sequences of change move from precontemplation to contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. Within this model, it is not uncommon for individuals to move forward and backwards across the stages as they undergo treatment, rather than change occurring within a linear fashion. The TTM helps to explain the lack of progress made by men in the early stages of participation in MBCPs, as they are in the precontemplation stage and may be unwilling to acknowledge their use of violence within intimate relationships.

A number of studies have demonstrated the value of applying a TTM framework to treatment of violence in intimate relationships [33]. Results show that an intervention will be more effective in changing behaviour when a man’s treatment readiness is high. When a person is at the early stages of change, they tend to downplay their behaviour and report less signs of anger, which is consistent with denial and minimisation, rather than acceptance of violent actions [34]. A study by Levesque, Gelles and Velicer[35] found that there were varying stages of readiness within a sample of 292 men participating in a domestic violence counselling group. Twenty-four per cent of men were in the precontemplative stage, 63% in the contemplative/preparation stage, and only 13% in the action stage. These results explained why there can be varying levels of engagement and progress shown by men within the same treatment group.

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a counselling strategy aligned to the TTM model, which assists clients to increase their readiness for change. During MI, clients are assisted to identify their stage within the TTM framework, and then work through how this will influence their behaviour change process. The key features of MI counselling include use of empathy, avoidance of argumentation, and support for self-efficacy. Results assessing the impacts of this approach show that men in the later stages of change were able to recognise that there were aspects of their lives that required the need for treatment, however those in the earlier stages of change were not consistently recognising that they needed to make changes to aspects of their lives [36]. Additionally, this was also an indicator of readiness for group therapy as opposed to individual treatment. This is a useful finding for understanding that individuals who are more accountable for their actions are more likely to engage in, and benefit from, the treatment process. It is therefore important to determine the stage of change prior to commencing treatment, in order to understand the potential causes, and variances, in individuals’ behaviour change.

3.2.4 Other models

Noting that the approach to perpetrator interventions can vary widely, there are a number of other models used around the world, which often draw on or, in some cases, underpin the frameworks listed above [37]. These include:

- Psychoeducational – This approach is based on the underlying theory that socio-political factors (entrenched gender inequality, patriarchal ideology) are the cause of family violence. The use of violence is viewed as deliberate and intentional, for the purpose of controlling and dominating women. These programs are typically well structured, however have been criticised for lacking empirical support, being ineffective at promoting self-engaged change, and being a one-size-fits-all approach that doesn’t theoretically account for violence in other situations (such as violence by women against men or those in same-sex relationships). The Duluth model falls within this category

- Psychotherapeutic - Viewing family violence as caused by personal dysfunction, these approaches stem from psychiatry and psychology, and use individualised programs. CBT is considered by some (but not all) to be a psychotherapeutic approach. Cognitive therapy, not to be confused with CBT, has a behavioural component and yet is different due to the relationship that develops between the therapist and the person who uses violence

- Family therapy and couples counselling - These interventions are used for particular types of perpetrators when typical group settings are considered inappropriate. While informed from different theoretical perspectives, these programs approach the issue of family violence as the result of a dysfunctional relationship. Given a majority of victims either stay with or return to the perpetrator, advocates of this approach argue this should be offered in order for the couple to work through their issues [38]. However, others argue that it places the victim in danger, and that it implies both parties are responsible for the violence.

Most approaches use some combination of psychoeducational and psychotherapeutic approaches. Many largely psychoeducational programs incorporate stress management, behaviour change and communication skill development. Further, as mentioned above, CBT is more typically used in conjunction with a gender-based power and control framework similar to the Duluth model.

- Matched interventions – Based on family violence having a number of causes, matched interventions are tailored to the perpetrator’s level of risk, criminogenic needs, and readiness to change. The intervention may be based on where the perpetrator falls according to a specific typology. For instance, family therapy is advocated by some as appropriate for couples with low-level, “situational violence”. The TTM of Change (discussed above) and motivational interviewing (MI) are two examples. While it has grown in popularity in Australia, evidence on the effectiveness of MI is inconclusive, as is its impact on retention rates.

3.3 Common treatment approaches

Keeping in mind the Duluth model (or a similar feminist analysis models) is dominant, research on MBCP approaches, while not always model specific, highlight the following common features of program delivery:

- Group sessions, one-on-one sessions, and a mix of both are used. One program identified (the New York Model for Batter Programs) only accepted court-mandated offenders, while most did not indicate this aspect of eligibility[39]

- Based on all the programs and jurisdictional standards reviewed, program length ranges from 6-40 sessions over 10-48 weeks [40]. However, programs of less than 20 weeks are often considered too short, as they do not take into account the time taken for participants to develop motivation for behaviour change

- While few details regarding intake and eligibility were identified, one program identified in the primary search had developed material specific for a particular cohort of offenders (Relationships Australia Victoria’s CALD MBCP)[41]

- A majority of states in the USA require an intake evaluation or assessment, in part to determine if other services (like AOD treatment) are also necessary. A review of police reports or other available court documents is also undertaken. Additionally, a review of previous contacts with health providers is also required by many states

- A large majority of programs (93% in the USA) include contact with the people experiencing violence [42]. This could include support, advocacy, counselling or appropriate referrals. For those that didn’t engage with victims, it is typically due to concerns for their safety[43].

In general, the highest risk (10-20%) offenders are not considered suitable for perpetrator intervention programs [44]. The most severe cases include individuals with high levels of psychopathy and a history of violence in other (than family violence) contexts. Issues that interfere with their ability to function in a group environment, such as substance abuse or mental health issues, may make an individual unsuitable until such issues are stabilised. In general, the content of these programs is the same whether you are a first time or repeat offender [45].

3.3.1 Measuring the success of MBCPs

There is limited evidence from the literature on perpetrator intervention program success factors and quality. Proving a clear evidence base for domestic violence perpetrator interventions has been “extremely difficult”, as noted by the ANROWs literature review [46].

A recent ANROWS review[47] identified that:

- formally articulating program logic models is beneficial (as they can guide evaluation), and MBCPs should be supported to do so

- strengthening safety and accountability planning can improve program quality

- engaging with victim survivors can improve program quality, and that this is currently an underfunded aspect of these programs.

Motivation is considered to be an important factor in program success. As mentioned above, program length is considered an important aspect of effectiveness, with 20 weeks being the minimum. Some men may take the first 12-15 weeks of a program to become motivated and ready to put in the work to change[48]. There are a number of other factors/predictors considered important, including having fewer contacts with the criminal justice system, and the absence of comorbid conditions (such as AOD or mental health).

A 2016 study[49] by researchers at Monash University considered program outcomes following MBCP participation over two years, for 300 participants across three states. The study found immediate and sustained falls in violent behaviour after program completion, with 65% of these men either violence free or almost violence free two years later. However, the study also noted a list of shortcomings of MBCPs, most of which fall under two categories:

- Inadequate service: Poor coordination between agencies, often no end-of-program assessment with referral to relevant supporting services, and limited length of program time.

- Too difficult to access: Long waiting times, and program unavailability in many areas.

Authors of a study by RMIT’s Centre for Innovative Justice (CIJ) [50], believe that while interventions in general act as ‘doorways to treatment’, they also pose risks. Some key risks that must be accounted for when referring people to MBCPs include whether a perpetrator may think a partner ‘dobbed him in’, and the agency’s ability to identify risks and collaborate with other agencies to address them.

Based on the existing evidence base, there is variable evidence that behaviour change programs have an impact on recidivism. One 2013 review of 30 studies found that about half of the interventions were more effective than a no-treatment control group [51]. The conclusion was more pessimistic if excluding studies with methodological flaws. Quantified outcome results for targeted cohort interventions (such as AOD, mental health, or CALD) were not identified. There is little evidence to support one type of intervention being more effective than another [52].

However, as noted by Project Mirabel in the UK [53], most existing literature on perpetrator programs is based on programs in the USA. Most men in these studies were court mandated, and not many of the programs offered support for victim/survivors. This makes translating these results for the Australian context difficult.

3.4 Treatment approaches for diverse cohorts – current evidence, and gaps in knowledge

It has already been mentioned that there is limited knowledge of how to address certain cohorts with complex needs in the context of perpetrator intervention programs. In many cases, these individuals are considered ineligible for perpetrator interventions, as their specific issues impact on their ability to be treated in a group environment. The Victorian MBCP minimum standards focus on how these factors impact on eligibility for the program while providing limited guidance on how to accommodate these cohorts[54]. As noted by the Royal Commission, for perpetrators ineligible to participate in perpetrator programs due to the complexity of their needs, “there is little else available to specifically address their family violence offending” [55].

The following sections outline evidence of current practices for tailoring support to the needs of specific populations when addressing family violence. Despite this, the current literature is very limited, and for some groups non-existent.

3.4.1 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who use violence

Programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be developed with a strong cultural foundation [56]. This includes designing them in a way that acknowledges the causes (e.g. impact of colonisation, stolen generation, substance abuse, entrenched poverty, experiences of trauma) and experiences of family violence in Aboriginal communities, which are more about compensation for a lack of value and esteem rather than patriarchal power [57].

Studies have noted the importance of healing approaches, which includes a holistic model encompassing the social, emotional, spiritual and cultural wellbeing of participants [58]. The concept of a ‘perpetrator’ is not commonly understood when working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who use violence, and therefore terminology should be focused on values and concepts that relate to the men’s circumstances, and the impact on the victim.

Additionally, it is vital that programs are developed and delivered with involvement from the local community. This will ensure that programs are designed to meet specific needs, with the local context in mind. For example, programs may be run at a local sporting club or on country, and include local Elders in the delivery of the program [59].

3.4.2 Culturally and linguistically diverse communities

To address the notion that the content of mainstream perpetrator programs are largely focussed on western concepts of family life, and often do not consider people who are not proficient in English, there has been an increasing emphasis on designing programs which are culturally specific. Typically, these programs are delivered in a group setting by a facilitator of the same cultural group, and the curriculum integrates cultural issues [60]. This format also provides social support to the men in addition to the focus on behviour change.

Programs specifically targeted at migrant or refugee men must recognise the experiences of trauma experienced by these men, and other risk factors contributing to their violent behaviour such as experiences of racism, social isolation, stress caused by immigration, and lack of access to other supports.

However it has been argued by some researchers that categorisation of people according to broad social groups may be ’reductionist’, by defining their identity in simplistic terms, and not recognising subtle cultural differences within larger population groups [61]. It is therefore important that people from specific cultural backgrounds should be given the option of both culturally specific or mainstream programs.

3.4.3 People with a disability

Intervention with this cohort requires sensitivity to the lack of able-bodied privilege that these perpetrators experience in many aspects of their lives. This includes experiences of marginalisation, lack of access to resources and opportunities, and disabling environments. Whilst these experiences do not excuse perpetration of violence, it is important to recognise how these individuals can be both perpetrators (of gender-based violence) and victims (of ableism) at the same time [62].

It is noted that for people with an intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury, there is less of a need to change the framework or the context via which family violence should be understood, but more about altering the mechanisms through which information is delivered. This may include adjustments such as the use of easy English materials, or taking more time to focus on specific aspects of course content [63].

3.4.4 LGBTI people who use violence

Due to the very few services for this cohort which exist in Australia, there is limited evidence regarding best practice approaches for people who use violence in LGBTI relationships. However a study conducted on intimate partner violence among sexual minority populations in the United States shows that there are a number of practice and policy implications for addressing the use of violence among this cohort [64]. This includes:

- removing other barriers leading to stress and a reduction in help-seeking, such as provision of housing or legal support

- understand the dual nature of victimisation and perpetration of violence commonly experienced by this cohort

- recognising the common negative social reactions that are often received by this cohort when accessing support

- use inclusive language, which does not address family violence as a heterosexual-only issue

- be aware of the issues faced by LGBTI people, without affiming stereotypes or stigmatising this population.

3.4.5 Women who use force

It is important to note that domestic abuse is gendered, and in its most dangerous form – coercive control – it is almost exclusively a crime perpetrated by men against women [65]. Women who use force in intimate relationships are almost always doing so in self-defence – a form of violence which has been labelled ’violent resistance’ [66]. A starc reminder of this fact is that when women kill their intimate partners, they are almost always killing a perpetrator. This was shown in a study undertaken by the NSW Domestic Violence Death Review, which found that 28 of 29 men killed by a female partner were violent perpetrators themselves [67]. Noting this context, the Royal Commission acknowledges that interventions for women who use force need to consider the environment in which the woman is using violence in an intimate relationship, and ’untangle’ the situations where this is in self-defence to her partner’s violence, where he is the primary agressor. It also noted the higher correlation between violence and other risk factors for this cohort, such as AOD and mental health issues, post-traumatic stress disorders, personality disorders, and a history of abuse[68].

The Royal Commission established four principles for developing programs for women who use violence, based on evidence from the United States:

- mainstream perpetrator programs are not sutiable for women who use violence, as these programs address coercive control which is not used by a majority of women

- interventions for women who use violence should address circumstances including persistent victimisation, self-defence and motivation for retaliation

- programs should consider the consequences that may result from refaining from violence, such as injury, feelings of being dominated, and the reactions of others

- interventions should acknowledge the unique and complex circumstances of individuals in this cohort [69].

3.4.6 People with complex needs

Given the prevalence of mental health and AOD issues among people who use violence, addressing these issues is an important part of the behaviour change process. Submissions to the Royal Commission highlighted the importance of an integrated response model whereby mental health and AOD services collaborate with family violence services to offer a joined-up response. Evidence was cited from combined AOD and MBCPs in the United States, whereby and integrative approach that targeted both addiction and aggressive behaviours had postive treatment outcomes for reducing both of these behaviours, compared with only targeting substance issues [70].

This focus on jointly addressing substance abuse and family violence in the one intervention was also demonstrated to be effective in a three year pilot program delivered by Communicare in Western Australia. In this model, men attending a MBCP were also allocated to an AOD case worker. They found that it was more effective to train MBCP facilitators in addiction work, rather than train AOD workers to address family violence, due to the nature of working with the men to address accountability and responsibility.

3.4.7 Rationale

Noting the limited, and often inconclusive nature of the current evidence on appropriate approaches for specific cohorts, it is intended that new Victorian programs will assist in building the evidence base for what works to acheive behaviour change for these population groups. Section 3.5 outlines the models that have been adopted in each of the new programs, in order to address the current gaps.

3.5 The Victorian response

3.5.1 Overview

Noting the current evidence presented in the section above, the models employed by the pilot programs have been designed or adapted to address the specific needs of these different cohorts, often drawing on approaches used overseas as they address gaps in the mainstream service delivery models typically used in Australia. As indicated Section 3.4, this often includes approaches such as trauma-informed practices, integrated response models, and cultural healing.

Table 3.1, below, outlines the specific models and approaches adopted by the new community-based interventions and case management trials, in order to address the identified gaps [71].

Table 3‑1 Program design features

|

Cohort |

Design features |

|

Women who use force (Baptcare/Berry St trial) |

|

|

People who use violence with cognitive impairment and/or learning disabilities (Bethany and Peninsula Health trials) |

|

|

LGBTI people who use violence (Drummond St trial and Thorne Harbour Health case management) |

|

|

Specific CALD cohorts (InTouch trial) |

|

|