- Date:

- 1 Mar 2023

How to use the place-based approaches guide

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Aboriginal people as the First Peoples and Traditional Owners and custodians of the land and water on which we all rely.

We acknowledge that Aboriginal communities are steeped in traditions and customs, and we respect this. We acknowledge the continuing leadership role of the Aboriginal community in striving to redress inequality and disadvantage and the catastrophic and enduring effects of colonisation.

Who is this guide for?

This guide is for all Victorian Public Service (VPS) employees interested in place-based approaches. It may also be useful to stakeholders from other sectors and can be shared with organisations, groups and community members working as part of a place-based approach.

Governments have a critical role in setting policy, providing funding and delivering services, but just as importantly, to support and enable community members, organisations and networks to be at the centre of place-based initiatives. This guide supports the Victorian whole-of-government Place-based Reform Agenda and builds on the Victorian Government’s A framework for place-based approaches released in 2020.

It outlines how governments, community groups and other stakeholders can collaborate effectively to achieve meaningful impacts for their local communities.

How was it developed?

This guide presents best-practice for place-based approaches that put the community at the centre.

Community can mean different things to different people. A community may refer to a group of people living in the set location, or a group of people with a shared set of values or perceptions. In this guide, the term ‘community’ includes both understandings, with an emphasis on identifying and strengthening what is shared and of benefit to the end goal of place-based approaches.

This guide has been developed in consultation with stakeholders and is based on research and the most up-to-date evidence on how government can support place-based initiatives more effectively to achieve local impact.

This includes:

- the 2020 Victorian Government A framework for place-based approaches

- literature on leading place-based practice, including Australian and international case studies and evaluations, and the literature review produced by the What Works for Victorian Place-based Approaches research project

- workshops and engagement with VPS staff and partners with experience working in place

- the 2019 Department of Health and Human Services’ departmental guide for place-based approaches, also developed in consultation with place-based initiatives across Victoria and VPS staff.

It provides practical ideas, advice, case studies, tools and resources to help you effectively design, implement and evaluate place-based initiatives.

How is it structured?

Place-based approaches are dynamic and community-specific so there is no single model. The guide is arranged by topic to help you easily find the information you need. You can read the whole guide or focus on the topics relevant to your situation or interests. Each topic provides an overview of key concepts and how each element works, supported by case studies, tools and additional resources.

If you don’t have the resources available to follow the steps exactly as described, see this as a starting point. You can adapt the recommendations and use the information that is relevant to your role.

If you are just getting started, refer to Chapter One: Understanding place-based approaches and how they evolve over time to get a better understanding of place-based approaches.

Case studies

The guide includes case studies of place-based initiatives in action to help you explore key concepts and ideas. As you read through each case study, consider:

- What is the challenge or opportunity the place-based initiative is trying to address? Who defined it?

- What is the specific role (delivering, enabling, coordinating, resourcing, promoting, securing, advising) of the government department(s) and partners?

- How is the initiative implemented, and its impact understood and measured?

- How might the funding, structure and timeframe of the case study’s approach differ from your context?

The best available research on Victorian place-based approaches

As part of the whole-of-government Place-based Reform Agenda, the Victorian Government funded a research project to consolidate and review evidence and build a better understanding of what works for place-based approaches in Victoria. The in-depth report What works for Place-based Approaches in Victoria aims to support decision-makers, funders and partners to increase the effectiveness of place-based initiatives to improve the wellbeing of Victorian communities.

Chapter One: Understanding place-based approaches and how they evolve over time

Overview

What are place-based approaches?

In this guide, place-based approaches describe community-led initiatives that target the specific circumstances of a place.

Place

The term ‘place’ commonly refers to a specific geographic area where people live, learn, work and recreate. ‘Place’ in the context of place- based approaches has no universal definition. The key is that the definition used by any initiative is meaningful and resonates with the local community.

Place-based approaches

The term ‘place-based approaches’ describes a diverse range of activities that target a place or location, to build on local strengths or respond to a complex social problem.

While there is no agreed definition of a place-based approach, the following definitions outline the main characteristics:

“A collaborative, long-term approach to build thriving communities delivered in a defined geographic location. This approach is ideally characterised by partnering and shared design, shared stewardship, and shared accountability for outcomes and impacts.” (Dart, 2019).

“An approach that targets the specific circumstances of a place and engages local people as active participants in development and implementation, requiring government to share decision-making.” (Victorian Government, 2020).

Why are they important?

Place-based approaches are recognised across the world as an important platform to respond to complex social and economic challenges, including the impact of natural disasters and pandemics.

Beyond immediate crisis and recovery needs, Victorian government departments are increasingly adopting place-based approaches to help achieve their objectives, including:

- implementing Recommendation 15 of the Royal Commission into Mental Health to establish place-based collectives in every local government area

- the expansion of ‘Our Place’ sites by then Department of Education and Training in partnership with the Colman Foundation

- establishing 20-minute Neighbourhoods as part of Plan Melbourne 2017-2050

- the Suburban Revitalisation program in 47 locations across Melbourne, where government partners with community, local government and businesses to support communities to thrive economically and socially

- continued support and advocacy for local place-based initiatives by Regional and Metropolitan Partnerships.

What do place-based approaches look like?

Place-based approaches are different from traditional, government-initiated programs or policy development processes. They go beyond service delivery to encompass social, economic and environmental governance and practice. Place-based approaches focus on building readiness and identifying shared desired outcomes to enable collaborative implementation (Victorian Government, 2020).

In contrast, ‘place-focused approaches’ (as defined in the Victorian Government’s A framework for place-based approaches) plan and adapt government services, programs and infrastructure to ensure they are meeting local needs. Government listens to community to adapt how business is done, but ultimately, has control over the objectives, scope and implementation.

Place-based approaches may be initiated by the community or by government; or even start out as a government-led, place-focused initiative and evolve to a more community-centred approach over time.

Place-based initiatives take a holistic approach, connecting existing government investment and services and building cross-sector collaborations that tackle the root causes of local challenges and build on opportunities. They can also build community resilience, trust, and cohesion, and empower communities through a sense of belonging, connection, and purpose.

Aboriginal communities have led the way in articulating and demonstrating the strength of community empowerment through self-determination. Place-based approaches share these same principles to provide impact to a broader range of vulnerable and disadvantaged communities.

Place-based approaches drive actions based on what local knowledge shows will make a real difference for the community. Because of this, no place-based initiative looks the same. Their strength lies in harnessing local community leadership, ideas and capacity to develop tailored and long-term solutions. Action might include coordinating and identifying gaps in local services, building grassroots social infrastructure and networks, or embedding policy changes in local institutions. Often a combination of strategies are used to address challenges and leverage opportunities for a local community.

Examples of place-based initiatives that have driven meaningful and outcomes and impact include:

- The Geelong Project, which has supported at risk young students from becoming homeless, disengaging in their education and leaving school early through building a ‘community’ of schools and service providers. It coordinates an accessible, integrated suite of services that a single organisation or sector could not achieve alone.

- Flemington Works which, as at June 2022, has supported 200 paid employment outcomes for 127 women and 73 young people residing at the Flemington Housing Estate, the establishment of 40 micro-enterprises in social change, hospitality and creative industries, and social procurement clauses being included in five Moonee Valley City Council labour force tenders.

Initiatives such as Go Goldfields in Victoria and Logan Together in Queensland are focused on creating a strong foundation for children, to give them the best chance in life. Logan Together has reduced smoking and overweight/obesity rates during pregnancy, improved newborn health, and increased the uptake of antenatal care. Since opening the ‘Village Connect’ maternity hub in Logan City in 2020, engagement has increased with over 85 per cent of mothers also participating in other activities offered, such as playgroups and gestational diabetes education sessions.

Place-based initiatives not only address the immediate and short-term needs of communities, but seek to breakdown structural barriers that trap communities in cycles of poverty and disadvantage.

Scotland’s New Deal for Communities Program and Victoria’s Neighbourhood Renewal Program (2001-2013) have helped address the inequality gap between communities by reducing unemployment, overall crime rates and feelings of social exclusion among residents in intervention locations.

When to use them?

A place-based initiative can be a powerful tool where an issue, problem or opportunity faced by a community:

- is multifaceted and complex

- cannot be addressed through services or infrastructure alone – existing government interventions have not had the desired impact

- does not have a clear solution and needs local people and organisations to be actively involved to find and develop meaningful responses

- requires a whole of government or cross-sectoral response

- requires a long-term response.

It’s important to remember that place-based approaches are not suitable in all circumstances.

They should complement rather than replace traditional government services and infrastructure and local community action.

Refer to Chapter Two: Working with local communities and government agencies to learn more.

Collective Impact

The Collective Impact (CI) framework is a method of place-based working that takes a structured approach to collaboration to address social challenges. This approach leverages all the resources and assets in a community to achieve change. It puts communities and people with diverse lived experience at the heart of defining local problems, using their strengths, voices and perspectives to co-create local solutions.

CI is a key methodology used internationally to address complex problems at the local level and achieve sustainable change with communities. The Tamarack Institute, based in Canada has identified that the approach is effective where complex disadvantage is experienced by a community and there is high community capacity and readiness to address the disadvantage.

An influential 2011 paper in the Stanford Social Innovation Review, outlined five core elements of the CI framework (Kania and Kramer, 2011):

- common agenda – defined by all partners

- shared measurement – with a focus on accountability and ongoing learning to support adaptative ways of working

- mutually reinforcing activities – leveraging resources across all partners to achieve shared priorities and achieving the best possible impact from available investment

- continuous communication and engagement – across partners to enable effective collaborative working, as well as engaging broadly and in an ongoing way, including with those with lived experience

- independent backbone structure – to facilitate and mobilise the collective effort. There is more on backbone organisations further in this section.

Since then, there have been further iterations of the CI framework, including the development of principles and phases of work, and a stronger recognition of the central importance of addressing equity. In 2021, the Stanford Social Innovation Review published a series of articles looking at the 10 years of the Collective Impact framework. The series was sponsored by the Collective Impact Forum, a program of FSG and the Aspen Institute Forum for Community Solutions, and documented the thinking as to how local practice has evolved as communities responded to their local context.

A range of articles have been published that reflect on the evolution of the CI framework, including Power and Collective Impact in Australia (Graham, Skelton and Paulson, 2021). It talks to how collective impact work has evolved in Australia, including how initiatives have adjusted the approach to address Australia’s community context, culture, and history.

The Collective Impact 3.0 paper (Cabaj and Weaver, 2016) was a significant evolution of the CI framework. It included a broader focus on measurement, evaluation and learning (MEL) and a more explicit focus on the importance of inclusive community engagement.

Role of government in collective impact efforts to achieve social change

Government can play a supportive and enabling role within each of the elements and phases of the CI framework. This can include the provision of funding and working internally across portfolios to bring a more ‘joined-up’ approach to engagement at the local level.

In Victoria, government funding has been provided to support the backbone functions of local place-based initiatives – for example, Go Goldfields, Beyond the Bell and the Greater Shepparton Lighthouse Project, as well as working internally to support local collaborative efforts.

Backbone organisations

Supporting ‘backbone’ organisations help to ensure that place-based initiatives can achieve their objectives.

The functions of a backbone need to be flexible and will evolve over time in response to the context and collaborative effort.

Key functions include:

- guiding vision and strategy

- facilitating collaboration across partners

- coordinating key actions and priorities

- managing shared measurement and learning practices to track progress and impacts

- enabling broad, inclusive engagement across the community, including those with lived experience

- mobilising resources to support the sustainability of the initiative.

Backbone functions can be held by a stand-alone organisation or distributed across local partners (with dedicated roles identified) depending on the size, scope and context of the Collective Impact effort. The Tamarak Institute has a great resource about different approaches to backbone structures.

You can find a further range of resources to better understand how to establish and support effective backbones by visiting the Collective Impact Forum and the Tamarack Institute.

How they work

The importance of government and community partnership

An innovative approach

Government is traditionally the largest service provider in communities, such as through schools, health, police and human services, and the largest funder of other service providers. This policy and funding dominance creates power imbalances. In addition, all levels of government often engage with local communities in ways that are disconnected and fragmented.

Place-based approaches provide a crucial platform for a more equal power relationship between governments and communities. Government must take the role of partner and enabler and genuinely share decision-making to define the outcomes that matter locally and the best ways to achieve them.

In placed-based approaches, governments go further than listening to or consulting with communities – they must actively support and enable local people and organisations to be involved in the decision making for their communities (Graham, Skelton, and Paulson, 2021).

This approach can challenge government systems, culture and staff. Traditional programmatic ways of working generally have more rigid accountability structures and contracts that can unintentionally undermine collaborative relationships and lead stakeholders to compete.

Effective place-based approaches challenge prescriptive and centralised processes by facilitating a more enabling and flexible operating environment where government agencies and staff work collaboratively with communities and across programs and portfolios.

A new type of role for government

Government needs to work differently to realise the full potential of place-based approaches.

While each place-based initiative is unique in terms of place, design and objectives, they often require similar capabilities from governments.

Government agencies will not always be the ‘drivers’; but instead, will enable and support local community action, which includes removing barriers that are sometimes created by government itself. Government agencies and staff need to relinquish some control and accept a level of uncertainty around priorities and implementation. They must work with community partners to provide:

- flexibility, so local partners can tailor their actions to what has the most impact on their community

- commitment, so community partners and government agencies have stability as they work over the long term (often 10 years or more) to tackle complex, multi-faceted issues

- trust, to support innovation and an environment where it’s safe to fail and learn.

The specific role (or roles) of government in a place-based initiative may evolve over time as the needs and preferences of the local community change, and at different stages of development and implementation.

Building the case for place-based work in the VPS

As place-based approaches can challenge traditional government ways of working, at times your role might be about building a coalition of support within government or securing authorisation to work in a non-traditional, more collaborative way to support a place-based initiative. It is important to:

- engage with leaders across government who will champion the work at the executive level

- design governance structures that enable the work

- build and maintain networks with staff across government who can advise, support, and authorise work

- utilise effective mechanisms to track impacts being achieved.

Building the case for place-based approaches within government often needs an assurance that a place-based initiative is robust and effective in its approach, and capable of achieving real change for community. Pointing to the evidence underpinning an initiative’s approach and supporting and promoting approaches that align with the evidence and best practice – as set out in this guide – is an important part of this process.

Key stages of development and implementation

There are some common stages typically involved in developing and implementing place-based initiatives. It is important to remember that many place-based initiatives are initiated by community players at the grass roots and government may not be involved at all in the early stages, but asked to provide support over time. Equally, the role of government will vary at any given stage according to the changing needs and priorities of the place-based initiative.

An overview of the common stages of a place-based approach is provided below. These stages are interlinked, rarely linear and there will often be a need or desire to loop back through one or two of the stages before moving to the next. It also provides an overview of the potential role of government at each stage. Government’s role is always to work in partnership as supporter and enabler with the community, rather than to take the lead.

A place-based initiative is a long-term undertaking and the steps that take place before on-the-ground action are critical to success. Some practice leading place-based initiatives spend up to 18 months in the first two stages.

Common stages of a place-based approach

1. Identify if a place-based approach is beneficial

Approach:

Work with local community stakeholders and use in-depth local knowledge to assess if a place-based approach is an appropriate response to local opportunities or challenges.

Potential role of government (subject to the needs and preferences of the community):

- Listen and learn – refer to Chapter Three: Working with diverse communities.

- Share knowledge, including government-held data and information – refer to Chapter Five: Data and evidence.

- Engage, connect and convene - help connect people and organisations at the local level (collaborative engagement) and across portfolios and levels of government (joined-up work) – refer to Chapter Seven: Collaborative governance and Chapter Two: Working with local communities and government agencies.

- Help identify local strengths as well as local capability and capacity gaps.

2. Assess readiness

Approach:

Work with the community to assess if it is ready to, or is already, self-mobilising around an opportunity or issue, and if government can meaningfully contribute. This considers if the required resources, leadership, connections and mindsets exist, or if they can be built.

Potential role of government (subject to the needs and preferences of the community):

- Listen and learn – refer to Chapter Three: Working with diverse communities.

- Share knowledge, including government-held data and information – refer to Chapter Five: Data and evidence.

- Engage, connect and convene - help connect people and organisations at the local level (collaborative engagement) and across portfolios and levels of government (joined-up work) – refer to Chapter Seven: Collaborative governance and Chapter Two: Working with local communities and government agencies.

- Help identify local strengths as well as local capability and capacity gaps.

3. Develop a shared vision and plan for change

Approach:

All community members and organisations with an interest come together to identify the change they want to make in the community. This is articulated with clear outcomes, measures of progress and impact, and a plan for making it happen, monitoring, evaluating and learning.

Potential role of government (subject to the needs and preferences of the community):

- Listen and learn – refer to Chapter Three: Working with diverse communities.

- Share knowledge, including government-held data and information – refer to Chapter Five: Data and evidence.

- Convene, influence and champion – use the convening power of government to promote collective buy-in for the shared vision and approach – refer to Chapter Seven: Collaborative governance.

- Plan for capability gaps through the provision of technical expertise or access to funding or resources.

- Provide flexible funding for action – refer to Chapter Six: Funding and resourcing models.

- Support the adoption of robust methodologies, tools and processes and the design of a monitoring, evaluation and learning framework – refer to Chapter Four: Monitoring, evaluation and learning.

4. Implement together

Approach:

Local partners such as community organisations, business, philanthropy and potentially government work collaboratively to resource and implement the plan. A local collaborative governance group oversees the implementation and can make changes.

Potential role of government (subject to the needs and preferences of the community):

- Listen, learn and support an adaptive approach – refer to Chapter Three: Working with diverse communities.

- Support the establishment of collaborative governance arrangements – refer to Chapter Seven: Collaborative governance.

- If appropriate, establish governance arrangements within government.

- Respond to identified capability gaps through the provision of technical expertise or access to funding or resources.

- Support the adoption of robust methodologies, tools and processes – refer to Chapter Four: Monitoring, evaluation and learning.

- Support the initiative to overcome system barriers and work collaboratively to improve system enablers – refer to Chapter Eight: Skills, capabilities and mindsets.

5. Embed a culture of learning and continual improvement

Approach:

All partners embed a culture of learning to bring in new ideas and keep the initiative effective and relevant. Evaluation enables them to assess if work is progressing shared outcomes, learn from failures and consider how practice and policy changes can be embedded into their organisations over the long term.

Potential role of government (subject to the needs and preferences of the community):

- Adopt a learning mindset – refer to Chapter Eight: Skills, capabilities and mindsets.

- Support a robust monitoring, learning and evaluation approach to capture and share learnings – refer to Chapter Four: Monitoring, evaluation and learning.

- Share knowledge, including government-held data and information – refer to Chapter Five: Data and evidence.

- Work collaboratively to identify and progress opportunities for improvement – refer to Chapter Seven: Collaborative governance.

6. Celebrate and Communicate success

Approach:

Everyone should be supportive of each other and ensure achievements are recognised and celebrated.

Potential role of government (subject to the needs and preferences of the community):

- Help to communicate well and widely

An alternative yet similar approach is the ‘Collaborative Cycle’ developed by Collaboration for Impact which outlines key stages of a place-based initiative, from the ‘Readiness Runway’ to ‘Achieving Transformation’.

It highlights the role of government and the critical enabling capabilities (such as expertise and skills) at each phase to achieve and sustain progress.

For more on this, see Platform C.

Key considerations

Be open to an ongoing, adaptive way of working as initiatives evolve

When working with a place-based initiative, processes and actions are dynamic and generally not linear. To be most effective, collaborative ways of working need an adaptive and flexible approach.

Clearly define your role and seek authorisation to work differently

Working in government, your traditional role may include contract management and/or performance monitoring. Holding these roles whilst participating in a collaborative initiative that asks you to disrupt business as usual to achieve better outcomes is challenging. Be clear that you will be taking a different role as part of the collaborative initiative and seek authorisation from your executive to do so.

Leverage existing capacity and knowledge

When working with communities, consider their existing platforms, groups or networks to help build capacity. Encourage natural leaders in the community and people with relevant skill sets or expertise, including those with lived experience, to get involved. These leaders often have a good understanding of the strengths and opportunities, wicked problems or underlying issues within their communities.

Refer to Chapter Two: Working with local communities and government agencies to learn more.

Build trust

Be mindful of the signals you send early in the process. Ensure that community voice is heard and valued and take the time to listen, learn and build relationships. This will help build trust that the intent to collaborate is genuine.

Help partners to navigate the complexity of government

Place-based practitioners report that government can sometimes seem impenetrable and confusing to navigate. Community members often don’t know who they need to speak to, how government priorities are determined or how decisions are made. You can help by connecting people to your colleagues in relevant government portfolio areas and explaining how government works, as well as setting up supportive internal governance arrangements (if appropriate).

Case study: Hands-up Mallee (Victoria)

History

Hands Up Mallee (HUM) is a place-based initiative in the Mildura local government area (LGA) that supports local responses driven by community- identified priorities, research and data. In 2016-17 HUM had over 1600 conversations with community members to determine its community aspiration of a ‘connected community, where families matter and children thrive’.

HUM partnerships

HUM brings local leaders and the community together to address social issues and improve health and wellbeing outcomes for children, young people and their families.

HUM negotiated Victorian Government funding through the adaptation of funding under Primary Care Partnerships in 2014. Since May 2020, HUM has been funded through the Stronger Places, Stronger People (SPSP) initiative, that involves a partnership with the Commonwealth and Victorian Governments. Alongside philanthropic funding and significant support from the Mildura Rural City Council, HUM is resourced to build trusting relationships and local partnerships over time and can work flexibly and responsively with the community.

The Victorian Government’s partnership with HUM and the Commonwealth Government through the SPSP initiative is a unique opportunity to understand how to best work with a broad range of stakeholders to support place-based approaches, including partnerships across three levels of government. By participating in SPSP, the Victorian Government seeks to understand what policies, funding approaches, culture changes and partnership approaches we need to make us better at this critical way of working.

HUM approach

A collaborative approach to boosting Covid-19 vaccination rates

In 2021, during an acute Covid-19 outbreak in the Mildura LGA, HUM was a key partner in a collaboration to develop and mobilise targeted community testing and vaccination clinics. The response model was based on the need in the local community to create equitable access and cultural safety for members of migrant, refugee and asylum seeker communities and people living in locations with lower vaccination rates.

HUM was able to leverage existing trusting relationships with community members, local services, funders and government to collaboratively set-up testing and vaccination clinics to meet community needs. The collaboration developed an adaptive pop-up clinic in neighbourhood parks and known community locations such as the Ethnic Communities Council. The clinics operated for several days at the same location and engaged trusted people from local communities to support community members in accessing the service.

This way of working was key to the success of the model. Trusted community members like Aunty Jemmes Handy, a respected Aboriginal Community Elder, were willing to work with the collaboration due to her existing and ongoing relationship with HUM’s work and way of working:

“We started talking about what was going on in our community, the whole community, not just one part of it. The organisations involved actually listened and took notice of what we wanted for a change”. (Aunty Jemmes Handy – Aboriginal Community Elder)

HUM and its partners Sunraysia Mallee Ethnic Communities Council, Sunraysia Community Health Services, Mildura Rural City Council, Mallee District Aboriginal Service and Sunraysia Medical Clinic understood the importance of the clinic location, representation of people running the clinic and the way of operating:

“You need a well-organised venue, bilingual staff, consent forms in different languages, all of that needs planning. I couldn’t do that by myself, neither could any of the other partners, but together we could do it. Together we did amazing work.” (Dr Mehdi – Sunraysia Medical Clinic GP)

Food relief

During the initial Covid-19 lockdowns in 2020, HUM drew on their existing relationships to convene more than 16 local organisations to respond to the community’s food security challenges. HUM and their partners quickly created a joint approach to emergency food relief through organisations pooling resources to respond more effectively to local needs and to strengthen the state-funded food relief approach. HUM and partners developed an adaptive system that saw food and essential supplies delivered to community members who needed them in a timely and targeted way to address identified gaps.

By the end of the lockdown period between March and November 2020, the collaborative work of HUM and their partners had supported a total of 3354 people through almost 900 immediate food parcels, 171 activity packs, and 194 referrals between organisations.

Visit www.handsupmallee.com

Case study: Our Place (Victoria)

History

The Colman Foundation (Colman), a philanthropic organisation, established the ‘Our Place’ approach based on the lessons learned from their work at Doveton College since 2012.

Our Place is a holistic place-based approach to support the education, health and development of all children and families in disadvantaged communities by utilising the universal platform of a school.

DET and Colman partnership

Based on the outcomes at Doveton College, in 2017 then Department of Education and Training (DET) and Colman signed a Partnership Agreement to establish the Our Place approach at 10 sites in vulnerable communities across Victoria for a period of 10 years.

Our Place approach

The Our Place approach supports children and families in vulnerable communities by providing:

- a single, welcoming point of entry to the school and early learning centre to engage with families and support continuity for children in their transition from kindergarten to school

- shared spaces to offer services such as maternal and child health, playgroup, general practitioners, paediatricians, immunisations, parent support groups, and adult education, training, volunteering and job seeking services

- access to tailored health, wellbeing and community services for families and children from one location

- community facilitators working on site to foster collaboration between service providers and help families and children connect to early childhood, education, health and wellbeing services.

As part of the establishment process, Colman consults with local service providers and the community to identify the services to be delivered at the site. This ensures they respond to the need of that specific community, avoid duplicating existing services and address any gaps in service delivery.

Governance

The DET and Colman Partnership governance structure is designed to:

- provide strategy and direction for the Our Place approach

- facilitate collaboration between partners, and oversee the establishment and implementation of the Our Place approach at sites

- support local implementation through the establishment of Site Partnership Groups.

Roles

DET has funded and built infrastructure at Our Place sites to provide a single point of entry for children and their families, and shared spaces for health service providers and community activities.

A partnership manager is also on site to support partner organisations to implement the Our Place approach. Colman has developed a central team to oversee all sites and support the implementation of the Our Place approach and the partnership.

Partnerships with local service providers and community groups are a key feature of the Our Place approach. These partners include:

- early childhood services

- local government

- other government departments

- community health services

- adult education providers

- community and cultural organisations.

Colman employs two community facilitators who work at Our Place sites to engage families and the community, identify and address barriers to implementation, and evaluate what is working and where further effort is needed.

Additional tools and resources

Victorian Government framework

A framework for place-based approaches, Victorian Government, 2020

Efficacy and history of place-based approaches

- Place-based approaches, Queensland Council of Social Service

- The effectiveness of place-based programmes and campaigns in improving outcomes for children: A literature review National Literary Trust, 2020

- Place-based approaches to regional development: Global trends and Australian implications, Australian Business Foundation, 2010

- Kania, Kramer and Senge, Waters of system change, FSG, 2018

- Lankelly Chase, Historical review of place-based approaches, funded by the Institute of Voluntary Action Research (IVAR), London, UK, 2017.

Chapter Two: Working with local communities and government agencies

Overview

Trusting relationships are critical to effective place-based work.

From a government perspective, these relationships are broadly understood as:

- ‘collaborative engagement’ in place – with community members, local leaders, and local organisations across sectors

- ‘joined-up work’ – relationships and ways of working with other public sector staff and organisations across portfolios and levels of government.

What is collaborative engagement in place?

A core part of a place-based initiative is finding the best way to connect with communities to achieve the desired outcomes. Collaborative engagement involves working with the community to identify existing strengths and capabilities by connecting with local leaders, networks, organisations and those with lived experience. Knowledge and experience is shared and an approach for solving the identified problem or leveraging an opportunity, is developed together. This chapter outlines how to understand and engage with diverse communities.

What is joined-up work?

The success of place-based approaches often depends on how well communities, stakeholders and government can take a ‘joined-up’ or holistic approach to achieve positive outcomes.

For the purpose of this guide, joined-up work is defined as ‘the coordination and collaboration of work by the VPS to support place-based approaches, and the authorisation to do so, within governments and external partners, including communities’.

The distinguishing characteristics of joined-up work is that there is an emphasis on objectives shared across organisational boundaries, such as design and delivery of a wide variety of policies, programs and services, as opposed to working solely within an organisation (Victorian State Government - State Services Authority, 2007).

Joined-up work can be through formal and informal partnerships or strategically structured governance arrangements. It can also include different ways of working across boundaries, ranging from interpersonal interactions based on relationships and networks to formal and interdependent arrangements based on mutual benefit and a common purpose (Buick, 2012).

Read more about how to support this way of working in Boundary spanning to improve community outcomes: A report on joined-up government.

Why is collaborative engagement and joined-up work important?

Local people and organisations are experts in their own experience and potential solutions. Communities need genuine ownership of a place- based initiative for it to harness local community leadership, ideas and capacity to develop tailored and long-term solutions. Therefore, government partnerships that empower the community to drive solutions are the most effective for place- based initiatives.

Joined-up government (at all levels) is critical to develop meaningful partnerships with community organisations and networks, and to drive solutions that span portfolio boundaries.

Five strategies for collaborative engagement and joined up work across government

Five strategies are recommended for effective collaborative engagement and joined-up work:

- Build readiness for change

- Plan for meaningful collaboration and engagement

- Adopt an appropriate collaboration and engagement approach

- Establish governance and power-sharing mechanisms

- Adopt mindsets for working in place.

When progressing work as part of a collaborative approach with communities, sometimes the pre-conditions and capacity to fully implement them will not be present, and decisions may need to be made on what to prioritise. Remember:

- a place-based initiative is long-term, and working collaboratively with communities to build readiness for change before on-the-ground action is critical to sustainable outcomes

- although place-based approaches have common stages, often the process is non-linear.

Refer to the ‘Key stages of development and implementation’ section in Chapter One: Understanding place-based approaches and how they evolve over time to learn more about the phases of place-based initiatives.

Strategy 1: Build readiness for change

It takes time and effort to build community and government readiness for change. This includes the preliminary steps to get people on board, build capacity and progress ways of working together in line with a shared agenda for change. Communities should be at the centre of any place-based approach and have the capacity to make decisions and drive action.

1.1 Leverage to build capacity

Think about existing platforms, groups or networks that can be leveraged to build capacity. Are there natural leaders in the community, or people with relevant skill sets or expertise that might be willing to get involved? Are there champions across government that could be engaged to support and promote the initiative? Identify opportunities for local people and organisations keen to be involved in leading the change process and working with the community and other stakeholders to design and implement the place-based approach.

Refer to Chapter Eight: Skills, capabilities and mindsets for tips on building teams for place-based approaches.

1.2 Build collaborative and shared effort

Work collaboratively across the community to build a shared understanding of the local context and identify and define the key local issue to focus on. This process is important to help local people build a connection with their ‘place’ and each other. The quality of these connections matters more than the number of relationships; people need to feel understood and accepted. Improved connectedness can lead to better health and wellbeing outcomes, especially for some of the most disadvantaged population groups in a community.

Think of opportunities to capitalise on connections and relationships across departments, with funded agencies and thought leaders to help build a coalition of support for the initiative.

1.3 Build social capital

Building the social capital of communities is a central feature of place-based approaches. High social capital drives thriving communities and builds individual and community resilience. This requires a balance of:

- bonding – close personal connections with family and friends, or people who are similar in crucial respects (inward-looking)

- bridging – ties with groups of individuals who differ (outward-looking)

- linking – ties with formal institutions.

Support and empower local leaders and community groups throughout the life of a place-based approach to serve and work with their communities. Plan from the start to deliver learning experiences and opportunities for community members and groups who are keen to participate.

A simple way to build social capital is to provide opportunities for people in a community to come together for a common purpose in their usual settings. For example, a gathering, such as a BBQ in a local park; places young people meet; an open access community facility such as a local library, or place of worship; or community celebration can help people connect in a comfortable, safe and meaningful way.

Many Victorian place-based approaches have successfully built social capital through a series of ‘kitchen conversations’. A kitchen conversation is when local community members connect informally with neighbours or friends, to talk to them about what the place-based initiative is trying to achieve. These events have a ‘multiplier effect’, where participants then engage with their own circles to carry the conversation and strengthen the community connection further. This peer-to-peer contact becomes self-sustaining and ultimately empowers the community to drive action.

Strategy 2: Plan for meaningful collaboration and engagement

Close, positive collaboration across a range of partners is critical to the success of a place-based approach. Think about who should be engaged and how?

2.1 Identify key partners, networks and platforms

Work with the place-based initiative to think broadly to identify the diversity of key partners, including those with lived experience, cultural diversity, and existing networks and platforms relevant to the place-based approach. Consider how to encourage a diversity of cohorts to participate or be represented, including groups that are less likely to be engaged in these processes: LGBTIQ+, Aboriginal people/s, CALD, people living with a disability and young people.

Always work to:

- ensure partners have the capacity, interest and positioning to take on the work at hand (Lankelly Chase, 2017)

- allow time to develop trust and build relationships from early on – the way trust and relationships are built will differ from group to group

- support and facilitate both formal and informal working structures with and across local partners.

Remember that other areas of government might be engaged or consulting with a community and that streamlining between government portfolios is good practice. Try to develop a good understanding of existing government work underway in an area or community, including through the Victorian Regional Partnerships and Metropolitan Partnerships.

It is also important to undertake due diligence and communicate clearly with stakeholders around accountabilities and the expectations of engagement, just as in working with partners in other areas of government business.

2.2 Map stakeholders

A key part of scoping an approach is to understand what the problem looks like for the community. Stakeholder mapping can help with this. This process should be ongoing and will identify affected community members and

organisations, and how best to engage with them throughout the initiative. Think about leveraging the knowledge and expertise from across government in mapping and working with diverse cohorts and communities including be connecting with areas across government that have ongoing relationships with stakeholder groups such as the Office for Disability or Regional Partnership and Metropolitan Partnership teams.

Local councils should ideally be involved and considered a critical partner in working in place. People with lived experience are also critical partners to provide an expert perspective to help guide design and implementation. Local academic institutions could also be engaged to build local capacity and leverage local knowledge and expertise.

Tips for mapping stakeholders:

- The usual suspects – start with those already engaged in the issue.

- The unusual suspects – complex issues often require looking beyond immediate stakeholders to work across industries and sectors so consider thinking ‘outside the box’ about who could be involved.

- Internal and other departments – reach out to program areas within the department in the target area, other departments and agencies.

- Community members – who are the people directly and indirectly experiencing the problem or who could benefit from the opportunity?

- Organisations, bodies and groups – which groups, businesses and organisations can contribute to the discussion and provide insight and knowledge?

- Check and revisit your list – ask who is already engaged and who else needs to be consulted, and revisit the list throughout the initiative, as it could change over time.

- Agreement – seek broad agreement on the stakeholder list, with the option to be flexible and change scope.

2.3 Engage local business and industry

There can be a lot of goodwill among local businesses around tackling social issues that affect their community, and a willingness to be involved. Local businesspeople can bring skills and insight into place-based approaches but may be unsure how they can contribute. You may need to tailor your approach to engaging local businesses to generate trust and explore how they can contribute at different stages of the initiative.

2.4 Leverage community and government champions

Most communities have existing local leaders who can work with you to champion the initiative, bring in new volunteers, advertise engagement activities and assist with day-to-day activities. More importantly, these people can be crucial to building trust and credibility in the community you are working in.

It is also critical to engage with the network of government champions at local, regional and central levels with prior experience working with communities and place-based approaches.

The Victorian Government’s How-to guide for public engagement is a great resource to help plan engagement

Strategy 3: Adopt an appropriate collaboration and engagement approach

In some cases, government’s role may be to collaborate with a place-based initiative to effectively engage directly with community members. As a collaborative partner in this work, design and test an overall engagement approach, including a clear definition of the purpose of your engagement activities. A range of tools and methodologies can be drawn on to do this.

Things to include in communication to the community:

- the reasons for the place-based initiative

- why it is important

- why local people should be actively engaged and drive the initiative.

It is important to be aware of consultation fatigue. Work with the place-based initiative to identify opportunities to ask the community how they want to be involved and what support they need – enable a spectrum of engagement.

Communities of Practice are a great platform for networking, relationship building, and knowledge sharing and could be considered as part of the engagement approach.

3.1 Work collaboratively to develop an engagement plan

Elements of a good engagement plan include:

- understanding the engagement to date – what has the community already undertaken and how have they been involved? What is the context of this engagement?

- the decision-makers – who has the authority to make decisions?

- purpose and objective – what are the challenges, and what are the desired outcomes?

- negotiables and non-negotiables – what aspects can the community have influence over, and what are driven by broader government policy settings?

- key questions – what information can the community provide to help with decision- making?

- identifying stakeholders – who are the stakeholders relevant to the initiative and what influence will each stakeholder have on the outcome?

- engagement roadmap – how will you report back on the information collected through engagement activities?

The Victorian Auditor General’s Public Participation in Government Decision-making: Better Practice Guide is a helpful resource to plan engagement.

Use the following six Victorian Government principles to help guide the engagement process:

- We are purposeful and our engagement is meaningful – we know why and who we are engaging

- We are inclusive – we provide opportunities and support to enable participation

- We are transparent – we clearly communicate what community can and cannot influence

- We inform communities – we provide relevant and timely information to the public

- We are accountable - we provide regular updates and complete the feedback loop

- We create value for the community and government – we value participants’ knowledge and time and their inputs in the decision-making process.

When engaging with First Nations communities and organisations, the principles of Aboriginal self-determination, as outlined in the Victorian Government’s Self-determination Reform Framework should be applied.

Refer to the ‘Working with First Nations communities’ section of Chapter Three: Working with Diverse Communities to learn more.

3.2 Public Participation Spectrum

A helpful tool to understand and plan collaboration and engagement is the International Association of Public Participation (IAP2) Public Participation Spectrum. The Spectrum helps define the public’s five potential roles in any participation process: inform, consult, involve, collaborate and empower.

You could work collaboratively with the place- based initiative to use these roles to define the level of participation required for each stakeholder group and individual. For example, some stakeholders may collaborate with the team to help propose solutions.

The Victorian Auditor-General’s Public Participation in Government Decision-making: Better Practice Guide includes a high-level framework which can help you decide how best to involve the public in decision making.

3.3 Co-design

Co-design is a process that uses creative and participatory methods that can meaningfully empower community stakeholders to design new products, services, and approaches in the context of place-based work.

For more on Co-design, see the ‘Methodologies, models and tools’ section of this chapter.

Strategy 4: Establish governance and power-sharing mechanisms for working in place

Establishing appropriate governance and power-sharing mechanisms is vital to ensuring inclusivity and transparency, which underpin many foundational principles for effective collaboration, engagement and joined-up work across government.

4.1 Establish governance structures

Governance arrangements create the basis for collective action and should enable meaningful involvement by the community and relevant government partners. Effective governance structures allocate responsibility, enable issues to be escalated and addressed, and guide the direction of place-based initiatives.

Also think about governance arrangements within government that could be established or leveraged to build support and buy-in; troubleshoot issues where government holds levers; coordinate across portfolio boundaries; or drive system change in response to barriers faced by place-based initiatives.

Refer to Chapter Seven: Collaborative governance to learn more.

4.2 Create power-sharing mechanisms

Governments can share control, influence and accountability with community by partnering in decision-making with local people and organisations. Ensuring that communities have authority within the initiative is a defining feature of place-based approaches. Consider how you and your team will share decision-making, influence, control and accountability with community members and other stakeholders. For example, this can happen through:

- collaboratively defining outcomes and objectives

- active participation in governance groups

- flexible funding that allows for local decision-making control over design and ongoing implementation

- designing evaluations and the process for incorporating learning.

Awareness of the structures and systems that produce or reinforce power is key to doing this work well. Power-mapping can be a useful tool to help you.

The scope of power-sharing will vary according to government’s appetite for risk and the capacity or readiness of local partners. Remember that local and broader systemic circumstances might change throughout the life cycle of the place-based initiative. This includes the political, economic and social conditions experienced by a community, such as the closure of a major local industry, a natural disaster, disturbances or other major events such as a community conflict.

Throughout a place-based initiative you should continually consider whether you are sharing the right level of decision-making, influence, control and accountability and if you are sharing them in the best way.

Things to ask when considering power-sharing:

- Are the people with the most knowledge and expertise supported to determine how to engage with an issue or opportunity?

- Who is not participating in power-sharing and why?

- Are Aboriginal peoples and communities being empowered consistently with the principles of self-determination, the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework and the Victorian Government Self-Determination Reform Framework. Refer to Chapter Three: Working with Diverse Communities for more information.

- Is partnered decision-making supporting stakeholders to progress towards an outcome? (Victorian Government, 2020).

Strategy 5: Adopt mindsets for working in place

The following mindsets are helpful when working in place.

5.1 Listen to the community and act accordingly

Government’s work with a place-based initiative is unlikely to be successful if it assumes what will be best for the community or imposes its ideas and priorities on the community. While research, evidence and data are all important when understanding issues in communities, context expertise – that is, community experience and understanding – is crucial. Provide plenty of opportunities for community members to be heard by government and key stakeholders, including what they would like to achieve, the outcomes they would like to see, and how they think change should happen.

5.2 Take an evidence-informed approach

Evidence-informed policy is about synthesising the best available data from a range of sources to guide decision-making and support a learning culture across all phases of a place-based initiative.

In the early phases, evidence informs the discovery of needs, what will be done and why. Communities should determine what it is that they want to achieve and – based on advice and information – how to achieve it.

Things to consider in the early phases:

- What is the problem, issue or opportunity? What does success look like? What outcome(s) are you seeking?

- How do you intend to respond to this problem, issue or opportunity?

- Is there evidence that this response works?

Remember, there are many different types of evidence, and the quality can vary depending on how the data was collected.

Refer to Chapter Five: Data and evidence to learn more about data quality and collection.

5.3 Foster a ‘safe to fail; free to learn’ environment

A place-based approach must have the flexibility and permission to make mistakes, fail and learn – this is part of their appeal. They provide an opportunity for small scale, relatively low-risk investment in innovative solutions to long-term and often enduring challenges, based on local evidence and expertise.

Place-based approaches provide a platform for collaborative work between a range of experts within a place, including the people whose lives the initiative is aiming to impact. It’s a platform to test and try new approaches, based on local evidence and expertise. Even if the approach experiences some failure, there will be valuable learnings, which brings the initiative closer to future success.

Working collaboratively to build an authorising environment – supported through governance, local decision-making and funding arrangements – that fosters a ‘safe to fail’ and learning culture, will help ensure that the place-based initiative can reach its full potential.

5.4 Progress with a systems-thinking frame of mind

When working collaboratively with a place-based initiative, try to think about the broader system rather than thinking about issues and solutions in terms of individual programs. A programmatic solution, such as an additional or bolstered service is not wrong, but it may not be sufficient to solve the problem or capitalise on an opportunity. Try to consider the system levers you think may create impact at the local level, and what system change might be required to better support a place-based initiative or place-based approaches more broadly.

These key principles of systems thinking may be helpful to understand and implement a place-based approach:

- The political, social, economic, and cultural systems impacting a local community are complex and cannot always be fully known.

- The understanding of any system comes from:

- drawing together diverse perspectives and utilising diverse methodologies

- focusing on the behaviours and dynamics of the system

- regular reflection and adaptation of process and continued, consistent assumption checking.

For more on systems change thinking, see The Waters of System Change by John Kania, Mark Kramer, and Peter Senge (2018).

5.5 Foster the conditions to support joined-up work

Government’s traditional approaches to policy and programs, including centrally determined targets and top-down performance management, can present barriers to joined-up work. Research confirms that fostering key supporting conditions can enable more effective collaboration and coordination across government portfolios and levels of government.

The central supporting condition is an ‘enabling culture, values and ethos’ for joined-up ways of working. Other key supporting conditions include:

- an enabling and flexible operating environment that supports joined-up and partnership ways of working

- strong and supportive authorisation from central government and local community leaders to undertake joined-up ways of working across government and with local communities

- VPS staff capabilities to confidently engage in joined-up and partnership ways of working.

For more on these supporting conditions and how to foster them, refer to Boundary spanning to improve community outcomes: A report on joined-up government, and Chapter Eight: Skills, capabilities, and mindsets for more on staff capabilities required for effective joined-up work.

How to work with key partners as part of a place-based initiative

Collaborative approaches support and guide people to achieve change, with an emphasis on working in agile and adaptive ways on cycles of small-scale testing and learning. Government partners can contribute to place-based initiatives by working with the community to draw on a broad range of methodologies and tools — whether established or newly developed (Victorian Government, 2020).

Methodologies, models and tools

There are many methodologies, models and tools to help as you collaborate with a place-based initiative to design and implement change.

The most suitable methodology and tool will depend on your purpose, context and objectives. A place-based initiative may draw primarily on one or use a mix to achieve agreed goals.

Methodologies

Methodologies that offer a structure to guide the implementation of place-based approaches through the different stages include:

- Collective Impact Framework – used for population-level and cohort-specific change outcomes (Cabaj and Weaver, 2016).

- Smart Specialisation Strategy – used for regional development outcomes (European Commission Joint Research Centre, 2011).

- Asset-based community development – used for local community-level strengthening (Nurture Development, 2018).

Models and tools

The following models and tools can help enable a place-based initiative to achieve its objectives.

It is good to understand the differences and nuances of each to determine which is best suited to a given context.

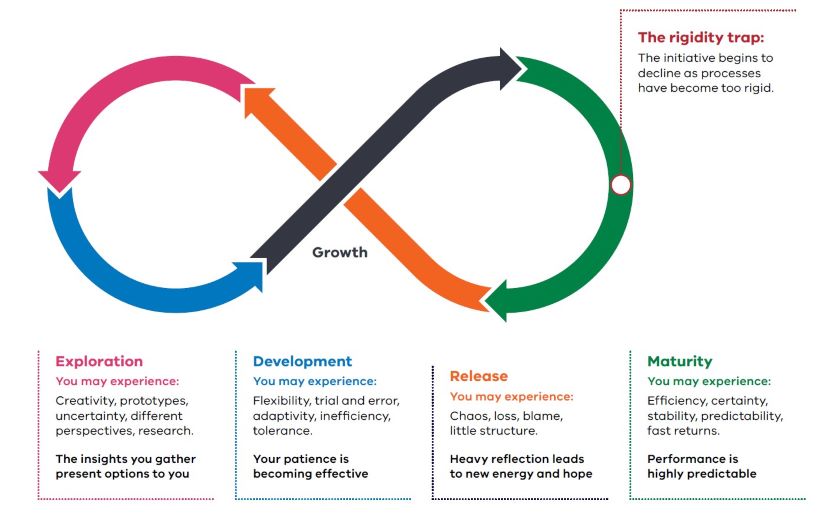

Adaptive cycle

The Adaptive Cycle model is a useful way to think about the place-based ‘journey.’ It suggests a robust place-based approach is one that continually develops and adapts over time, as a cyclical process based on continuous improvement.

The model features five stages, as illustrated in Figure 2.1. It commences with exploration to develop options and then progresses into the development stage. As an initiative becomes more established, it will experience growth before reaching a state of maturity. Should processes become too rigid, the initiative may be unable to adapt to changing circumstances, leading to a decline its effectiveness.

While decline may appear to represent a ‘failure,’ it provides an opportunity to pause for reflection. This release regenerates the initiative as those involved begin to explore new options.

Co-design and human-centred design

Co-design and human-centred design (HCD) puts people front and centre when designing a solution to an issue. The place-based initiative may find it useful to draw on co-design and HCD principles as it works with local stakeholders to identify the solutions that are best suited to the local context and desired level of change.

Auckland Codesign Lab has further information on how to effectively use co-design and a range of resources.

Place-based system change approach

A Place-based Systemic Change (PBSC) is defined by “the area it covers and the relationships, practices, assumptions and ultimately systems which shape that place. It’s not something that skims the surface nor something that is simply replicable from place to place” (Hitchin, 2020).

A PBSC approach often focuses on digging deeper into issues, relationships and the dynamic nature of a place to learn how social problems can be shifted.

Case study: The Greater Shepparton Lighthouse Project (Victoria)

History

The Greater Shepparton Lighthouse Project (Lighthouse Project) is a community-driven place-based initiative that aims to systemically address the issues impacting children and young people living in Greater Shepparton.

Lighthouse Project and Victorian Government Partnership

The six-year funding commitment by the Victorian Government has enabled the Lighthouse Project to build cross-sectoral relationships across the local community.

Lighthouse Project approach

The Lighthouse Project utilises volunteers, data interrogation, collaboration, innovation and systems thinking to create change and develop responsive solutions to support all children and young people to thrive. These were critical in harnessing local ‘know-how’, resources and expertise to respond to food shortages experienced by the local community during the Covid-19 lockdown.

The emphasis by the Lighthouse Project on community voice – from the 1000 conversations and ongoing engagement through their ‘Collaborative Leadership Tables’ (community decision-making forums) – meant that they stay attuned to community needs and strengths.

During the 2021 lockdown, almost 20,000 Greater Shepparton residents were placed in Tier One, 14-day isolation with little warning. The impact of this was widespread, leading to the closure of several schools and the collapse of supermarket delivery systems due to overdemand and staff shortages. A large proportion of families and residents were forced to self-isolate without access to essential food supplies or their own support networks.

The Lighthouse Project has a strong history of activating community volunteers, with over 500 volunteers contributing to their initiatives prior to the impacts of Covid-19 in 2020. The 2021 outbreak activated their network of volunteers to support GV Cares, a Lighthouse Project driven local network for critical food relief that factored in the differing needs of Greater Shepparton’s diverse community.

Through the outbreak in September 2021:

- 300+ community members offered their support, with 150 volunteers directly assisting with food deliveries

- at the peak of need, volunteers delivered to approximately 570 homes a day

- approximately 50% of people isolating were beneficiaries of the food relief

- over 2000 individual requests were processed

- a total of 4814 deliveries were completely processed through the Triage Team

- approximately $150,000 donated to GV Cares initiative.

Through this work, the Lighthouse Project supported the public health response by ensuring community members had key supplies and connections to be able to stay at home during this critical time.

The Lighthouse Project credits this success to activating ‘local people with high social capital [who helped] to make this happen’ and believes that the power of place-based initiatives is ‘the local ‘know how’ that government can sometimes struggle to tap into’.

Visit www.gslp.com.au

Additional tools and resources

- Social Capital Building Toolkit, Sander and Lowney, 2006

- Tools for Systems Thinkers: Systems Mapping, Acaroglu, 2017

- Collaborative Change Cycle, Platform C

- Human-centred design Playbook, Victorian Government, 2020

Chapter Three: Working with diverse communities

Overview

What is diverse community?

Community empowerment and effective, ongoing collaboration and engagement is essential for successful place-based approaches. However, there are many different communities in Australia. So, when working with a place-based initiative, it’s important to consider diverse community needs and their cultures while working with them.

Diverse, inclusive and liveable communities create the social and physical environments which support people to thrive. Being able to safely identify with culture and/or identity is empowering for individuals, families and communities. Valuing and respecting diversity means people accept differences amongst individuals and groups, which fosters wellbeing and is part of the social capital of a community.

This chapter provides guidance around working with diverse communities including:

- First Nations communities

- culturally and linguistically diverse communities

- people with disability

- people of different ages

- LGBTIQ+ communities.

This chapter also highlights the importance of understanding intersectionality – appreciating that many factors combine to form an individual’s identity and experience, and that different aspects of a person’s identity can expose that person to overlapping forms of discrimination and marginalisation. This includes gender, class, ethnicity and cultural background, religion, disability and sexual orientation.

Why is it important?

Communities are not homogenous, and individuals within communities may experience overlapping and interdependent forms of discrimination, vulnerability and disadvantage (Victorian Government, 2021). Engaging and collaborating with diverse communities will also help to ensure that the full spectrum of a community’s strengths, skills, perspectives and talents can contribute to the success of a place-based initiative.

Working with diverse communities and population groups

Groups within a community can experience place differently, so try to recognise and find ways to work with less prominent or marginalised groups. A one-size-fits-all approach to collaboration and engagement can unintentionally discriminate against parts of the community, limiting valuable contributions. Using engagement methods that are responsive to people’s needs helps make it possible for different community members to fully participate in place-based approaches.

The Victorian Government’s How-to guide for public engagement is a great resource to help plan engagement.

Working with First Nations communities

The key starting point to working with First Nations communities is to work in a way that enables self-determination as outlined in the Victorian Government’s Self-Determination Reform Framework.

It states that future government action to advance Aboriginal self-determination will be driven by 11 guiding principles:

- human rights

- partnership

- investment

- cultural integrity

- decision making

- equity

- commitment

- empowerment

- accountability

- Aboriginal expertise

- cultural safety.

The Victorian Government has also identified four self-determination enablers which it must act on to make self-determination a reality:

- prioritise culture

- address trauma and support healing

- address racism and promote cultural safety

- transfer power and resources to communities.

Self-determination goes beyond engagement and consultation, to Aboriginal ownership, decision-making and control over the issues that affect their lives.

The Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework self-determination continuum provides a powerful representation of working in place with Aboriginal communities to advance self-determination ranging from informing community through to transferring decision-making control.

When working with an Aboriginal community, ensure that the methods of engaging are agreed on by the community before engagement commences.

You should also be mindful of the wider context of collaboration and the process of trust building in progress. Treaty in Victoria is a significant component of this broader context.

Cultural safety is also vitally important when working with Aboriginal communities. Cultural safety is about shared respect, knowledge and understanding, empowering people and enabling them to contribute and feel safe to be themselves. (Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency, 2010)

It is important to acknowledge and be respectful of the deep experience and knowledge of Aboriginal peoples, their diverse communities and cultures.

Things to consider when working with Aboriginal communities

Be aware of attitudes to and previous experiences of consultation

Aboriginal communities may view consultation negatively, as they may have been asked to participate in numerous consultation processes, have experienced poor consultation, or might be doubtful about how their opinions will be respected. They may be concerned there is no avenue for genuine change.

Seek a range of views

A place-based initiative will benefit from working with a range of different Aboriginal organisations, communities, cultural and language groups and respected individuals. Involve Aboriginal peoples from the very outset of your initiative and use informal communication channels where appropriate.

Develop trust and rapport with the community

Develop positive relationships with elders, local Aboriginal role models, peak organisations and their senior management and build trust – take sufficient time and resources to communicate how the advice/ information given by Aboriginal communities will be used and how you will report back on outcomes. Choose appropriate catering and venues and consider transport needs for elders in the Aboriginal community with whom you are working.

Communicate carefully and respectfully on sensitive issues

Be mindful when working with Aboriginal people around difficult issues that may have touched their lives, and of their spiritual and cultural beliefs, including protocols around ‘men’s business’ and ‘women’s business’. Use the right words and forms of address and ensure that all relevant information is accurate and clearly presented. Refer to the Victorian Public Sector Commission Aboriginal Cultural Capability Toolkit for more information.

Where to start

Start with key local groups, networks and organisations such as:

- Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (ACCOs)

- Local Aboriginal Education Consultative Groups (LAECGs)

- Aboriginal Engagement Networks

- Local Aboriginal Engagement teams in your department

- Local Aboriginal Governance engagement structures

- The Aboriginal Children and Young People’s Alliance

- Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (VACCHO)

- Aborigines Advancement League

- Aboriginal cooperatives providing health and community services.

Engaging Culturally and Linguistically Diverse communities