Overview

Trusting relationships are critical to effective place-based work.

From a government perspective, these relationships are broadly understood as:

- ‘collaborative engagement’ in place – with community members, local leaders, and local organisations across sectors

- ‘joined-up work’ – relationships and ways of working with other public sector staff and organisations across portfolios and levels of government.

What is collaborative engagement in place?

A core part of a place-based initiative is finding the best way to connect with communities to achieve the desired outcomes. Collaborative engagement involves working with the community to identify existing strengths and capabilities by connecting with local leaders, networks, organisations and those with lived experience. Knowledge and experience is shared and an approach for solving the identified problem or leveraging an opportunity, is developed together. This chapter outlines how to understand and engage with diverse communities.

What is joined-up work?

The success of place-based approaches often depends on how well communities, stakeholders and government can take a ‘joined-up’ or holistic approach to achieve positive outcomes.

For the purpose of this guide, joined-up work is defined as ‘the coordination and collaboration of work by the VPS to support place-based approaches, and the authorisation to do so, within governments and external partners, including communities’.

The distinguishing characteristics of joined-up work is that there is an emphasis on objectives shared across organisational boundaries, such as design and delivery of a wide variety of policies, programs and services, as opposed to working solely within an organisation (Victorian State Government - State Services Authority, 2007).

Joined-up work can be through formal and informal partnerships or strategically structured governance arrangements. It can also include different ways of working across boundaries, ranging from interpersonal interactions based on relationships and networks to formal and interdependent arrangements based on mutual benefit and a common purpose (Buick, 2012).

Read more about how to support this way of working in Boundary spanning to improve community outcomes: A report on joined-up government.

Why is collaborative engagement and joined-up work important?

Local people and organisations are experts in their own experience and potential solutions. Communities need genuine ownership of a place- based initiative for it to harness local community leadership, ideas and capacity to develop tailored and long-term solutions. Therefore, government partnerships that empower the community to drive solutions are the most effective for place- based initiatives.

Joined-up government (at all levels) is critical to develop meaningful partnerships with community organisations and networks, and to drive solutions that span portfolio boundaries.

Five strategies for collaborative engagement and joined up work across government

Five strategies are recommended for effective collaborative engagement and joined-up work:

- Build readiness for change

- Plan for meaningful collaboration and engagement

- Adopt an appropriate collaboration and engagement approach

- Establish governance and power-sharing mechanisms

- Adopt mindsets for working in place.

When progressing work as part of a collaborative approach with communities, sometimes the pre-conditions and capacity to fully implement them will not be present, and decisions may need to be made on what to prioritise. Remember:

- a place-based initiative is long-term, and working collaboratively with communities to build readiness for change before on-the-ground action is critical to sustainable outcomes

- although place-based approaches have common stages, often the process is non-linear.

Refer to the ‘Key stages of development and implementation’ section in Chapter One: Understanding place-based approaches and how they evolve over time to learn more about the phases of place-based initiatives.

Strategy 1: Build readiness for change

It takes time and effort to build community and government readiness for change. This includes the preliminary steps to get people on board, build capacity and progress ways of working together in line with a shared agenda for change. Communities should be at the centre of any place-based approach and have the capacity to make decisions and drive action.

1.1 Leverage to build capacity

Think about existing platforms, groups or networks that can be leveraged to build capacity. Are there natural leaders in the community, or people with relevant skill sets or expertise that might be willing to get involved? Are there champions across government that could be engaged to support and promote the initiative? Identify opportunities for local people and organisations keen to be involved in leading the change process and working with the community and other stakeholders to design and implement the place-based approach.

Refer to Chapter Eight: Skills, capabilities and mindsets for tips on building teams for place-based approaches.

1.2 Build collaborative and shared effort

Work collaboratively across the community to build a shared understanding of the local context and identify and define the key local issue to focus on. This process is important to help local people build a connection with their ‘place’ and each other. The quality of these connections matters more than the number of relationships; people need to feel understood and accepted. Improved connectedness can lead to better health and wellbeing outcomes, especially for some of the most disadvantaged population groups in a community.

Think of opportunities to capitalise on connections and relationships across departments, with funded agencies and thought leaders to help build a coalition of support for the initiative.

1.3 Build social capital

Building the social capital of communities is a central feature of place-based approaches. High social capital drives thriving communities and builds individual and community resilience. This requires a balance of:

- bonding – close personal connections with family and friends, or people who are similar in crucial respects (inward-looking)

- bridging – ties with groups of individuals who differ (outward-looking)

- linking – ties with formal institutions.

Support and empower local leaders and community groups throughout the life of a place-based approach to serve and work with their communities. Plan from the start to deliver learning experiences and opportunities for community members and groups who are keen to participate.

A simple way to build social capital is to provide opportunities for people in a community to come together for a common purpose in their usual settings. For example, a gathering, such as a BBQ in a local park; places young people meet; an open access community facility such as a local library, or place of worship; or community celebration can help people connect in a comfortable, safe and meaningful way.

Many Victorian place-based approaches have successfully built social capital through a series of ‘kitchen conversations’. A kitchen conversation is when local community members connect informally with neighbours or friends, to talk to them about what the place-based initiative is trying to achieve. These events have a ‘multiplier effect’, where participants then engage with their own circles to carry the conversation and strengthen the community connection further. This peer-to-peer contact becomes self-sustaining and ultimately empowers the community to drive action.

Strategy 2: Plan for meaningful collaboration and engagement

Close, positive collaboration across a range of partners is critical to the success of a place-based approach. Think about who should be engaged and how?

2.1 Identify key partners, networks and platforms

Work with the place-based initiative to think broadly to identify the diversity of key partners, including those with lived experience, cultural diversity, and existing networks and platforms relevant to the place-based approach. Consider how to encourage a diversity of cohorts to participate or be represented, including groups that are less likely to be engaged in these processes: LGBTIQ+, Aboriginal people/s, CALD, people living with a disability and young people.

Always work to:

- ensure partners have the capacity, interest and positioning to take on the work at hand (Lankelly Chase, 2017)

- allow time to develop trust and build relationships from early on – the way trust and relationships are built will differ from group to group

- support and facilitate both formal and informal working structures with and across local partners.

Remember that other areas of government might be engaged or consulting with a community and that streamlining between government portfolios is good practice. Try to develop a good understanding of existing government work underway in an area or community, including through the Victorian Regional Partnerships and Metropolitan Partnerships.

It is also important to undertake due diligence and communicate clearly with stakeholders around accountabilities and the expectations of engagement, just as in working with partners in other areas of government business.

2.2 Map stakeholders

A key part of scoping an approach is to understand what the problem looks like for the community. Stakeholder mapping can help with this. This process should be ongoing and will identify affected community members and

organisations, and how best to engage with them throughout the initiative. Think about leveraging the knowledge and expertise from across government in mapping and working with diverse cohorts and communities including be connecting with areas across government that have ongoing relationships with stakeholder groups such as the Office for Disability or Regional Partnership and Metropolitan Partnership teams.

Local councils should ideally be involved and considered a critical partner in working in place. People with lived experience are also critical partners to provide an expert perspective to help guide design and implementation. Local academic institutions could also be engaged to build local capacity and leverage local knowledge and expertise.

Tips for mapping stakeholders:

- The usual suspects – start with those already engaged in the issue.

- The unusual suspects – complex issues often require looking beyond immediate stakeholders to work across industries and sectors so consider thinking ‘outside the box’ about who could be involved.

- Internal and other departments – reach out to program areas within the department in the target area, other departments and agencies.

- Community members – who are the people directly and indirectly experiencing the problem or who could benefit from the opportunity?

- Organisations, bodies and groups – which groups, businesses and organisations can contribute to the discussion and provide insight and knowledge?

- Check and revisit your list – ask who is already engaged and who else needs to be consulted, and revisit the list throughout the initiative, as it could change over time.

- Agreement – seek broad agreement on the stakeholder list, with the option to be flexible and change scope.

2.3 Engage local business and industry

There can be a lot of goodwill among local businesses around tackling social issues that affect their community, and a willingness to be involved. Local businesspeople can bring skills and insight into place-based approaches but may be unsure how they can contribute. You may need to tailor your approach to engaging local businesses to generate trust and explore how they can contribute at different stages of the initiative.

2.4 Leverage community and government champions

Most communities have existing local leaders who can work with you to champion the initiative, bring in new volunteers, advertise engagement activities and assist with day-to-day activities. More importantly, these people can be crucial to building trust and credibility in the community you are working in.

It is also critical to engage with the network of government champions at local, regional and central levels with prior experience working with communities and place-based approaches.

The Victorian Government’s How-to guide for public engagement is a great resource to help plan engagement

Strategy 3: Adopt an appropriate collaboration and engagement approach

In some cases, government’s role may be to collaborate with a place-based initiative to effectively engage directly with community members. As a collaborative partner in this work, design and test an overall engagement approach, including a clear definition of the purpose of your engagement activities. A range of tools and methodologies can be drawn on to do this.

Things to include in communication to the community:

- the reasons for the place-based initiative

- why it is important

- why local people should be actively engaged and drive the initiative.

It is important to be aware of consultation fatigue. Work with the place-based initiative to identify opportunities to ask the community how they want to be involved and what support they need – enable a spectrum of engagement.

Communities of Practice are a great platform for networking, relationship building, and knowledge sharing and could be considered as part of the engagement approach.

3.1 Work collaboratively to develop an engagement plan

Elements of a good engagement plan include:

- understanding the engagement to date – what has the community already undertaken and how have they been involved? What is the context of this engagement?

- the decision-makers – who has the authority to make decisions?

- purpose and objective – what are the challenges, and what are the desired outcomes?

- negotiables and non-negotiables – what aspects can the community have influence over, and what are driven by broader government policy settings?

- key questions – what information can the community provide to help with decision- making?

- identifying stakeholders – who are the stakeholders relevant to the initiative and what influence will each stakeholder have on the outcome?

- engagement roadmap – how will you report back on the information collected through engagement activities?

The Victorian Auditor General’s Public Participation in Government Decision-making: Better Practice Guide is a helpful resource to plan engagement.

Use the following six Victorian Government principles to help guide the engagement process:

- We are purposeful and our engagement is meaningful – we know why and who we are engaging

- We are inclusive – we provide opportunities and support to enable participation

- We are transparent – we clearly communicate what community can and cannot influence

- We inform communities – we provide relevant and timely information to the public

- We are accountable - we provide regular updates and complete the feedback loop

- We create value for the community and government – we value participants’ knowledge and time and their inputs in the decision-making process.

When engaging with First Nations communities and organisations, the principles of Aboriginal self-determination, as outlined in the Victorian Government’s Self-determination Reform Framework should be applied.

Refer to the ‘Working with First Nations communities’ section of Chapter Three: Working with Diverse Communities to learn more.

3.2 Public Participation Spectrum

A helpful tool to understand and plan collaboration and engagement is the International Association of Public Participation (IAP2) Public Participation Spectrum. The Spectrum helps define the public’s five potential roles in any participation process: inform, consult, involve, collaborate and empower.

You could work collaboratively with the place- based initiative to use these roles to define the level of participation required for each stakeholder group and individual. For example, some stakeholders may collaborate with the team to help propose solutions.

The Victorian Auditor-General’s Public Participation in Government Decision-making: Better Practice Guide includes a high-level framework which can help you decide how best to involve the public in decision making.

3.3 Co-design

Co-design is a process that uses creative and participatory methods that can meaningfully empower community stakeholders to design new products, services, and approaches in the context of place-based work.

For more on Co-design, see the ‘Methodologies, models and tools’ section of this chapter.

Strategy 4: Establish governance and power-sharing mechanisms for working in place

Establishing appropriate governance and power-sharing mechanisms is vital to ensuring inclusivity and transparency, which underpin many foundational principles for effective collaboration, engagement and joined-up work across government.

4.1 Establish governance structures

Governance arrangements create the basis for collective action and should enable meaningful involvement by the community and relevant government partners. Effective governance structures allocate responsibility, enable issues to be escalated and addressed, and guide the direction of place-based initiatives.

Also think about governance arrangements within government that could be established or leveraged to build support and buy-in; troubleshoot issues where government holds levers; coordinate across portfolio boundaries; or drive system change in response to barriers faced by place-based initiatives.

Refer to Chapter Seven: Collaborative governance to learn more.

4.2 Create power-sharing mechanisms

Governments can share control, influence and accountability with community by partnering in decision-making with local people and organisations. Ensuring that communities have authority within the initiative is a defining feature of place-based approaches. Consider how you and your team will share decision-making, influence, control and accountability with community members and other stakeholders. For example, this can happen through:

- collaboratively defining outcomes and objectives

- active participation in governance groups

- flexible funding that allows for local decision-making control over design and ongoing implementation

- designing evaluations and the process for incorporating learning.

Awareness of the structures and systems that produce or reinforce power is key to doing this work well. Power-mapping can be a useful tool to help you.

The scope of power-sharing will vary according to government’s appetite for risk and the capacity or readiness of local partners. Remember that local and broader systemic circumstances might change throughout the life cycle of the place-based initiative. This includes the political, economic and social conditions experienced by a community, such as the closure of a major local industry, a natural disaster, disturbances or other major events such as a community conflict.

Throughout a place-based initiative you should continually consider whether you are sharing the right level of decision-making, influence, control and accountability and if you are sharing them in the best way.

Things to ask when considering power-sharing:

- Are the people with the most knowledge and expertise supported to determine how to engage with an issue or opportunity?

- Who is not participating in power-sharing and why?

- Are Aboriginal peoples and communities being empowered consistently with the principles of self-determination, the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework and the Victorian Government Self-Determination Reform Framework. Refer to Chapter Three: Working with Diverse Communities for more information.

- Is partnered decision-making supporting stakeholders to progress towards an outcome? (Victorian Government, 2020).

Strategy 5: Adopt mindsets for working in place

The following mindsets are helpful when working in place.

5.1 Listen to the community and act accordingly

Government’s work with a place-based initiative is unlikely to be successful if it assumes what will be best for the community or imposes its ideas and priorities on the community. While research, evidence and data are all important when understanding issues in communities, context expertise – that is, community experience and understanding – is crucial. Provide plenty of opportunities for community members to be heard by government and key stakeholders, including what they would like to achieve, the outcomes they would like to see, and how they think change should happen.

5.2 Take an evidence-informed approach

Evidence-informed policy is about synthesising the best available data from a range of sources to guide decision-making and support a learning culture across all phases of a place-based initiative.

In the early phases, evidence informs the discovery of needs, what will be done and why. Communities should determine what it is that they want to achieve and – based on advice and information – how to achieve it.

Things to consider in the early phases:

- What is the problem, issue or opportunity? What does success look like? What outcome(s) are you seeking?

- How do you intend to respond to this problem, issue or opportunity?

- Is there evidence that this response works?

Remember, there are many different types of evidence, and the quality can vary depending on how the data was collected.

Refer to Chapter Five: Data and evidence to learn more about data quality and collection.

5.3 Foster a ‘safe to fail; free to learn’ environment

A place-based approach must have the flexibility and permission to make mistakes, fail and learn – this is part of their appeal. They provide an opportunity for small scale, relatively low-risk investment in innovative solutions to long-term and often enduring challenges, based on local evidence and expertise.

Place-based approaches provide a platform for collaborative work between a range of experts within a place, including the people whose lives the initiative is aiming to impact. It’s a platform to test and try new approaches, based on local evidence and expertise. Even if the approach experiences some failure, there will be valuable learnings, which brings the initiative closer to future success.

Working collaboratively to build an authorising environment – supported through governance, local decision-making and funding arrangements – that fosters a ‘safe to fail’ and learning culture, will help ensure that the place-based initiative can reach its full potential.

5.4 Progress with a systems-thinking frame of mind

When working collaboratively with a place-based initiative, try to think about the broader system rather than thinking about issues and solutions in terms of individual programs. A programmatic solution, such as an additional or bolstered service is not wrong, but it may not be sufficient to solve the problem or capitalise on an opportunity. Try to consider the system levers you think may create impact at the local level, and what system change might be required to better support a place-based initiative or place-based approaches more broadly.

These key principles of systems thinking may be helpful to understand and implement a place-based approach:

- The political, social, economic, and cultural systems impacting a local community are complex and cannot always be fully known.

- The understanding of any system comes from:

- drawing together diverse perspectives and utilising diverse methodologies

- focusing on the behaviours and dynamics of the system

- regular reflection and adaptation of process and continued, consistent assumption checking.

For more on systems change thinking, see The Waters of System Change by John Kania, Mark Kramer, and Peter Senge (2018).

5.5 Foster the conditions to support joined-up work

Government’s traditional approaches to policy and programs, including centrally determined targets and top-down performance management, can present barriers to joined-up work. Research confirms that fostering key supporting conditions can enable more effective collaboration and coordination across government portfolios and levels of government.

The central supporting condition is an ‘enabling culture, values and ethos’ for joined-up ways of working. Other key supporting conditions include:

- an enabling and flexible operating environment that supports joined-up and partnership ways of working

- strong and supportive authorisation from central government and local community leaders to undertake joined-up ways of working across government and with local communities

- VPS staff capabilities to confidently engage in joined-up and partnership ways of working.

For more on these supporting conditions and how to foster them, refer to Boundary spanning to improve community outcomes: A report on joined-up government, and Chapter Eight: Skills, capabilities, and mindsets for more on staff capabilities required for effective joined-up work.

How to work with key partners as part of a place-based initiative

Collaborative approaches support and guide people to achieve change, with an emphasis on working in agile and adaptive ways on cycles of small-scale testing and learning. Government partners can contribute to place-based initiatives by working with the community to draw on a broad range of methodologies and tools — whether established or newly developed (Victorian Government, 2020).

Methodologies, models and tools

There are many methodologies, models and tools to help as you collaborate with a place-based initiative to design and implement change.

The most suitable methodology and tool will depend on your purpose, context and objectives. A place-based initiative may draw primarily on one or use a mix to achieve agreed goals.

Methodologies

Methodologies that offer a structure to guide the implementation of place-based approaches through the different stages include:

- Collective Impact Framework – used for population-level and cohort-specific change outcomes (Cabaj and Weaver, 2016).

- Smart Specialisation Strategy – used for regional development outcomes (European Commission Joint Research Centre, 2011).

- Asset-based community development – used for local community-level strengthening (Nurture Development, 2018).

Models and tools

The following models and tools can help enable a place-based initiative to achieve its objectives.

It is good to understand the differences and nuances of each to determine which is best suited to a given context.

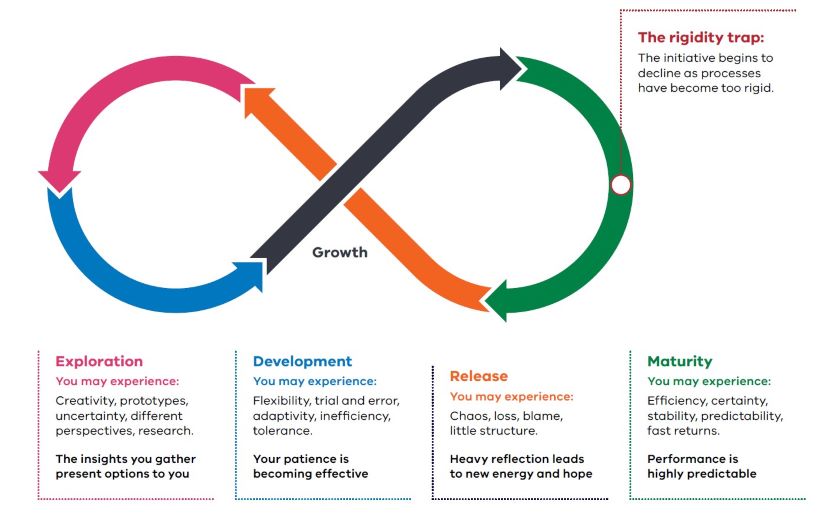

Adaptive cycle

The Adaptive Cycle model is a useful way to think about the place-based ‘journey.’ It suggests a robust place-based approach is one that continually develops and adapts over time, as a cyclical process based on continuous improvement.

The model features five stages, as illustrated in Figure 2.1. It commences with exploration to develop options and then progresses into the development stage. As an initiative becomes more established, it will experience growth before reaching a state of maturity. Should processes become too rigid, the initiative may be unable to adapt to changing circumstances, leading to a decline its effectiveness.

While decline may appear to represent a ‘failure,’ it provides an opportunity to pause for reflection. This release regenerates the initiative as those involved begin to explore new options.

Co-design and human-centred design

Co-design and human-centred design (HCD) puts people front and centre when designing a solution to an issue. The place-based initiative may find it useful to draw on co-design and HCD principles as it works with local stakeholders to identify the solutions that are best suited to the local context and desired level of change.

Auckland Codesign Lab has further information on how to effectively use co-design and a range of resources.

Place-based system change approach

A Place-based Systemic Change (PBSC) is defined by “the area it covers and the relationships, practices, assumptions and ultimately systems which shape that place. It’s not something that skims the surface nor something that is simply replicable from place to place” (Hitchin, 2020).

A PBSC approach often focuses on digging deeper into issues, relationships and the dynamic nature of a place to learn how social problems can be shifted.

Case study: The Greater Shepparton Lighthouse Project (Victoria)

History

The Greater Shepparton Lighthouse Project (Lighthouse Project) is a community-driven place-based initiative that aims to systemically address the issues impacting children and young people living in Greater Shepparton.

Lighthouse Project and Victorian Government Partnership

The six-year funding commitment by the Victorian Government has enabled the Lighthouse Project to build cross-sectoral relationships across the local community.

Lighthouse Project approach

The Lighthouse Project utilises volunteers, data interrogation, collaboration, innovation and systems thinking to create change and develop responsive solutions to support all children and young people to thrive. These were critical in harnessing local ‘know-how’, resources and expertise to respond to food shortages experienced by the local community during the Covid-19 lockdown.

The emphasis by the Lighthouse Project on community voice – from the 1000 conversations and ongoing engagement through their ‘Collaborative Leadership Tables’ (community decision-making forums) – meant that they stay attuned to community needs and strengths.

During the 2021 lockdown, almost 20,000 Greater Shepparton residents were placed in Tier One, 14-day isolation with little warning. The impact of this was widespread, leading to the closure of several schools and the collapse of supermarket delivery systems due to overdemand and staff shortages. A large proportion of families and residents were forced to self-isolate without access to essential food supplies or their own support networks.

The Lighthouse Project has a strong history of activating community volunteers, with over 500 volunteers contributing to their initiatives prior to the impacts of Covid-19 in 2020. The 2021 outbreak activated their network of volunteers to support GV Cares, a Lighthouse Project driven local network for critical food relief that factored in the differing needs of Greater Shepparton’s diverse community.

Through the outbreak in September 2021:

- 300+ community members offered their support, with 150 volunteers directly assisting with food deliveries

- at the peak of need, volunteers delivered to approximately 570 homes a day

- approximately 50% of people isolating were beneficiaries of the food relief

- over 2000 individual requests were processed

- a total of 4814 deliveries were completely processed through the Triage Team

- approximately $150,000 donated to GV Cares initiative.

Through this work, the Lighthouse Project supported the public health response by ensuring community members had key supplies and connections to be able to stay at home during this critical time.

The Lighthouse Project credits this success to activating ‘local people with high social capital [who helped] to make this happen’ and believes that the power of place-based initiatives is ‘the local ‘know how’ that government can sometimes struggle to tap into’.

Visit www.gslp.com.au

Additional tools and resources

- Social Capital Building Toolkit, Sander and Lowney, 2006

- Tools for Systems Thinkers: Systems Mapping, Acaroglu, 2017

- Collaborative Change Cycle, Platform C

- Human-centred design Playbook, Victorian Government, 2020

Updated