- Date:

- 24 Aug 2023

Our equal state: Victoria’s gender equality strategy and action plan is our roadmap for the next four years of action in gender equality.

When it comes to gender equality, Victoria leads the nation. We’ve taken great strides towards making the state fairer and more equal for all. We’ve invested in the things that matter to women and girls, and we’re creating more opportunities for them than ever before.

Visit the Our gender equality strategy webpage to find out more about our progress.

Summary

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement of Country

We acknowledge Victoria’s Aboriginal communities and their ongoing strength in practising the world’s oldest living culture. We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands and waters on which we live, work, learn and play, and pay our respects to their Elders past and present.

We acknowledge the ongoing leadership role of the Aboriginal community in addressing and preventing family violence and violence against women. We join with First Peoples to end family violence from all communities, and work towards gender equality.

We recognise that self-determination is the vital guiding principle for all Victorian Government actions to address past injustices and to create a shared future based on Aboriginal sovereignty.

Treaty and Truth-telling in Victoria

We are deeply committed to Aboriginal self-determination and to supporting Victoria’s Treaty and Truth-telling processes. We acknowledge that Treaty will have wide-ranging impacts for the way we work with Aboriginal Victorians. We seek to create respectful and collaborative partnerships and develop policies and programs that respect Aboriginal self-determination and align with Treaty objectives.

We acknowledge that Victoria’s Treaty process will provide a framework for the transfer of decision-making power and resources to support self-determining Aboriginal communities to take control of matters that affect their lives. We commit to working proactively to support this work in line with the aspirations of Aboriginal Victorians.

We recognise the diversity of Aboriginal people living in Victoria. While the terms ‘Koorie’ or ‘Koori’ are often used to describe Aboriginal people of southeast Australia, we use ‘Aboriginal’ or ‘First Nations’ to include all people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who live in Victoria.

Recognition of victim survivors of family violence

We acknowledge the terrible impact of family violence on women, families and communities, and the strength and resilience of victim survivors, including children, who have experienced, or are currently experiencing, family violence.

We pay respects to those who did not survive and to their family members and friends. They remain at the forefront of our work.

Family violence services and support

If you have experienced violence or sexual assault and need immediate or ongoing help, contact 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) to talk to a counsellor from the national sexual assault and domestic violence hotline. For confidential support and information, contact Safe Steps’ 24/7 family violence response line on 1800 015 188.

If you have concerns about your safety or that of someone else, please contact the police in your state or territory, or call Triple Zero (000) for emergency help.

Language statement

Language is important and can change over time. Words can have different meanings for different people.

We acknowledge that our approach to gender equality must always be trans and gender diverse inclusive. We celebrate the critical role of trans and gender diverse people in the fight for gender equality. A person’s gender is their own concept of who they are and how they interact with other people. Many people understand their gender as being a man or woman. Some people understand their gender as a combination of these or neither. A person’s gender may or may not exclusively correspond with their assigned sex at birth.

When we say women, that word always includes trans and gender diverse women and sistergirls.

Some data and research in this document is limited to the gender binary of men and women, in particular cisgendered and heterosexual men and women. It does not always account for the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and gender diverse, intersex and queer (LGBTIQ+) people. We acknowledge that there is more work to do to improve intersectional data collection and use across the Victorian Government.

The words ‘our’ and ‘we’ in this document refer to the Victorian Government.

Thank you

The Victorian Government thanks everyone in the community who shared their time, expertise and experiences with us to develop this gender equality strategy and action plan. Our work is deeply strengthened as a result of these contributions.

Foreword from the Victorian Government

When it comes to gender equality, Victoria leads the nation. We’ve taken great strides towards making the state fairer and more equal for all. We’ve invested in the things that matter to women and girls, and we’re creating more opportunities for them than ever before.

Since 2016, our landmark gender equality reforms have been guided by Safe and strong: a Victorian gender equality strategy. Safe and strong laid the critical foundations to make Victoria a more equal place – for everyone. We used all our available levers – legislation, policy development, investment, budgeting and public sector employment – to drive gender equality. And we’ve worked collaboratively with communities and experts to pave the way for lasting change.

In 2020, we became the first jurisdiction in Australia to enshrine public sector gender equality laws through the Gender Equality Act 2020. The Act targets the drivers of gender inequalities, including the gender pay gap, gendered workplace segregation, under-representation in leadership roles, lack of workplace flexibility and sexual harassment.

Then, in 2021, we became the first state to introduce gender responsive budgeting. Every year, we analyse and consider the impact of investment decisions on women at every stage of the budget process. And we’ll enshrine gender responsive budgeting in law, so it can keep guiding investment into the future.

Alongside these critical frameworks, we’ve made practical, targeted investments to directly address women’s needs and work toward improving outcomes for them:

- Our nation leading Best Start, Best Life reforms will make childcare more accessible and affordable for Victorians, unlocking women’s participation in the workforce.

- We’re giving women’s health the focus, funding and respect it deserves with a comprehensive package which includes new services, better research, significant investments – and a crucial inquiry into women’s pain management.

- We’re the first place in Australia to ensure every government school student has universal access to free pads and tampons – and next, we’ll provide them at up to 700 public sites across the state from 2024.

These are solutions to problems that have often been overlooked, or misunderstood – and all of them were developed by women, for women. It shows the power and the potential of public policy made by people, for people. And initiatives like this can only come out of a Cabinet where women have a voice, and are properly represented. That’s why we’re proud to have reached gender parity in Cabinet in 2018, and continue to have a majority of women sitting in Cabinet today.

But when it comes to gender equality, we know there’s always more to do – and we’re not slowing down. It’s an honour to present Our equal state, Victoria’s gender equality strategy and first State gender equality action plan. Through Our equal state, we’re building on our work to drive gender equality – and laying a path towards it for generations to come.

We recognise that addressing gender inequality requires systemic and structural reform, and the Victorian Government is in a unique position to lead this work. But addressing the bias and discrimination embedded across society needs community-wide action. In other words, we can’t go it alone: we need to work in partnership with the private and community sectors, media, sporting and volunteer groups, and all levels of government. Because gender equality is everyone’s business, and we’ll work to make sure it stays that way.

The Hon. Daniel Andrews MP, Premier of Victoria

The Hon. Natalie Hutchins MP, Minister for Women

Our equal state – at a glance

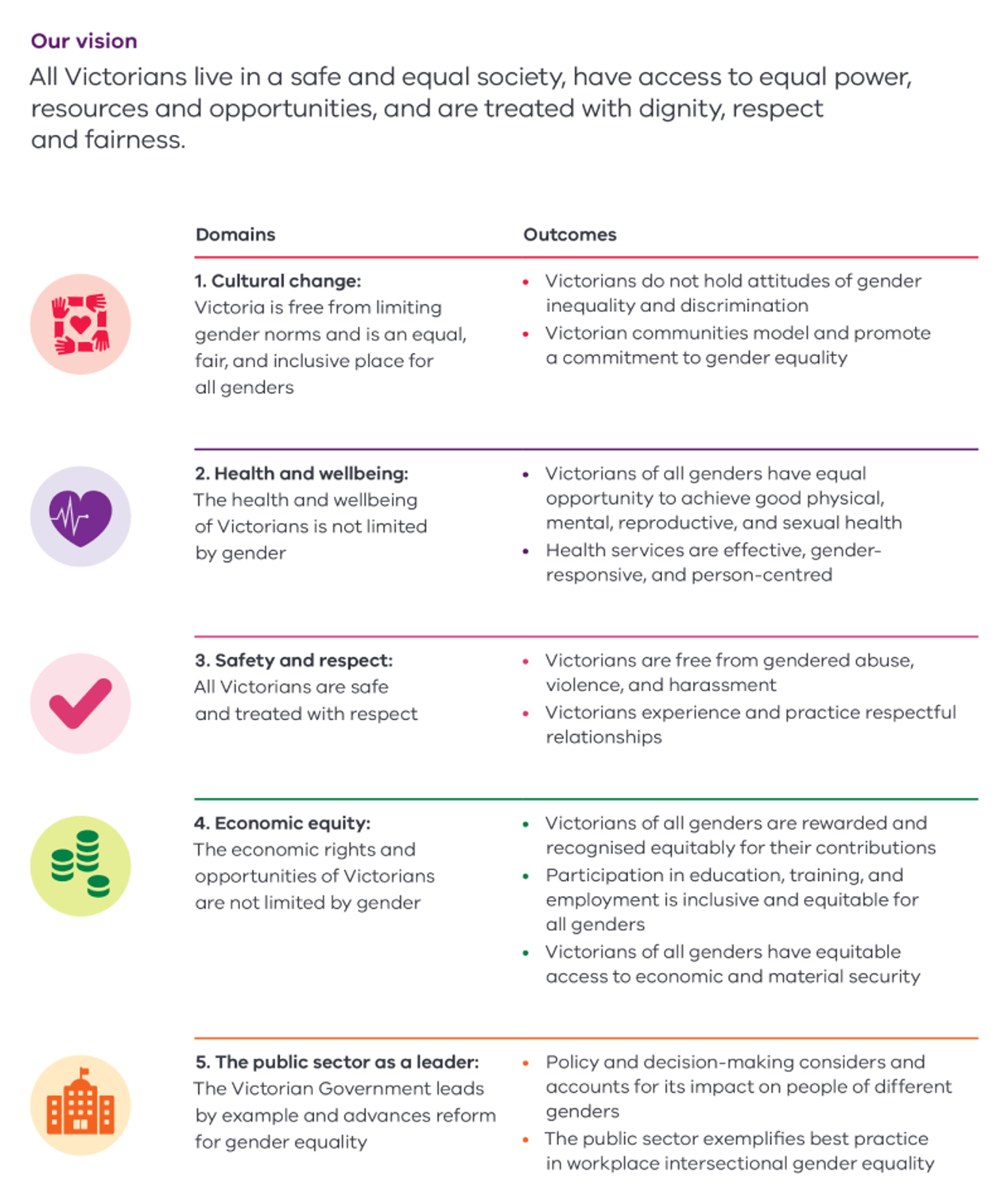

Our vision

All Victorians live in a safe and equal society, have access to equal power, resources and opportunities, and are treated with dignity, respect and fairness.

Gender equality across life stages

- Childhood and youth

- Adulthood

- Older age

- All life stages

What we aim to achieve

- Cultural change – Victoria is free from limiting gender norms and is an equal, fair and inclusive place for all genders.

- Health and wellbeing – the health and wellbeing of Victorians is not limited by gender.

- Safety and respect – all Victorians are safe and treated with respect.

- Economic equity – the economic rights and opportunities of Victorians are not limited by gender.

- The public sector as a leader – the Victorian Government leads by example and advances reforms for gender equality.

Guiding principles

- We will focus on structural and cultural change.

- We support Aboriginal self-determination.

- We will centre inclusion, diversity and accessibility.

- Gender equality is everyone’s responsibility.

Actions

- Our actions include new commitments, areas for future work, and successful programs and policies.

A life course approach to gender equality

Our equal state: Victoria’s gender equality strategy and action plan 2023–2027 takes a life course approach to gender equality.

Delivering the state gender equality action plan

Our equal state is Victoria’s first state gender equality action plan (GEAP), as required under the Gender Equality Act 2020 (the Act).

This strategy will drive action across government

Government policies, programs and services affect people in different ways due to gender.

Shaping the strategy

Community, sector and cross-government consultation inform Our equal state.

A life course approach to gender equality

Our equal state: Victoria’s gender equality strategy and action plan 2023–2027 takes a life course approach to gender equality, focusing on:

- childhood and youth

- adulthood

- older age.

Gender and other intersecting inequalities start before birth and accumulate and grow over time changing the trajectory of people’s lives. They also have long-term impacts over generations. Families and communities can experience intergenerational trauma, poverty and disadvantage.

Delivering the state gender equality action plan

Our equal state is Victoria’s first state gender equality action plan (GEAP), as required under the Gender Equality Act 2020 (the Act). [1]

The Act is the first of its kind in Australia and it is recognised globally as leading workplace gender equality legislation. It’s the strongest tool available to us to make meaningful change towards a gender equal Victoria, and beyond.

Victoria’s GEAP is our framework for coordinated action to build the attitudinal, behavioural, structural and normative change required to improve gender equality. It is based on the principles set out in the Act: [2]

- All Victorians should live in a safe and equal society, have access to equal power, resources and opportunities and be treated with dignity, respect and fairness.

- Gender equality benefits all Victorians regardless of gender.

- Gender equality is a human right and precondition to social justice.

- Gender equality brings significant economic, social and health benefits for Victoria.

- Gender equality is a precondition for the prevention of family violence and other forms of violence against women and girls.

- Advancing gender equality is a shared responsibility across the Victorian community.

- All human beings, regardless of gender, should be free to develop their personal abilities, pursue their professional careers and make choices about their lives without being limited by gender stereotypes, gender roles or prejudices.

- Gender inequality may be compounded by other forms of disadvantage or discrimination that a person may experience on the basis of Aboriginality, age, disability, ethnicity, gender identity, race, religion, sexual orientation and other attributes.

- Women have historically experienced discrimination and disadvantage on the basis of sex and gender.

- Special measures may be necessary to achieve gender equality.

We will track our progress towards gender equality in Victoria in line with the Act. We will report back to parliament every 2 years, using the outcomes framework in this strategy.

The Baseline report – 2021 workplace gender audit data analysis, published by the Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector, informs Our equal state. The Baseline report provides an overview of gender inequality in the Victorian public sector. It helps us understand the challenges and gaps and where to focus to improve gender equality.

References

[1] Victorian Government, Gender Equality Act 2020, section 50, Victorian Government, 2020. https://www.legislation.vic.gov.au/as-made/acts/gender-equality-act-2020

[2] Victorian Government, Gender Equality Act 2020, section 6, Victorian Government, 2020. https://www.legislation.vic.gov.au/as-made/acts/gender-equality-act-2020

This strategy will drive action across government

Government policies, programs and services affect people in different ways due to gender. Our equal state guides us to think about the lived experiences of women and gender diverse people in legislation, policies, programs and government spending.

We recognise that achieving gender equality needs action from all parts of government. This strategy outlines a strong agenda for long-term, systemic and structural reform – backed by practical investments – to change the way we make decisions and how we address bias and discrimination embedded in our society.

In Victoria, we have built a strong, linked system that will drive gender equality. Our work broadly falls into 3 categories:

- work that exclusively and directly delivers against this strategy and the Victorian gender equality outcomes framework

- work that is broader than gender equality that contributes to the Victorian gender equality outcomes framework

- all other policies, programs and services that have a direct and significant impact on the public and need a gender impact assessment, as per the Gender Equality Act 2020.

Shaping the strategy

Many voices have influenced and improved this strategy

Community, sector and cross-government consultation inform Our equal state.

We received more than 450 contributions from individuals and organisations representing:

- the community and not-for-profit sectors

- the private sector

- unions

- universities and researchers

- Aboriginal women

- culturally diverse women

- LGBTIQ+ Victorians

- women with disability

- single mothers

- victim survivors of family and gendered violence.

We also undertook a statewide survey through Engage Victoria, which included:

- more than 1,000 unique visitors to the website

- 18 written submissions

- 29 survey responses.

We continue to deliver the Inquiry into economic equity for Victorian women

Our equal state focuses our work as we continue to enact the recommendations of the Inquiry into economic equity for Victorian women. The independent inquiry panel delivered its landmark report to the Victorian Government in January 2022. It had 31 recommendations and 26 findings about workplace and economic inequity for women. Carol Schwartz AO chaired the expert panel, alongside Liberty Sanger OAM and James Fazzino.

Introduction – Our equal state

The journey so far

This strategy builds on the solid foundation set by Safe and strong.

Gender inequality affects us all

Gender equality is not a ‘women’s issue’. The effects of gender inequality touch all parts of our community. Gender stereotypes negatively affect people of all genders.

People experience gender inequality differently

Our equal state takes an intersectional approach to gender equality that considers compounding forms of disadvantage or discrimination.

Gender inequality is a driver of violence against women

Gender inequality underlies family violence and violence against women. This violence continues to be a significant risk to the lives of Victorian women.

Gender equality requires sustained, transformative and generational change

Our equal state has a strong focus on improving outcomes for Victorian women, girls and gender diverse people.

The journey so far

This strategy builds on the solid foundation set by Safe and strong.

Safe and strong set out a framework for enduring and sustained action over time. We achieved – and often, pushed well beyond – the founding reforms we announced in 2016. Since then, we have prioritised gender equality in government action and investment. We introduced new laws, fought for groundbreaking policy reform and led innovative programs. From family violence and sexual harassment reforms, to targeted economic support for women and workforce strategies, we’ve laid critical foundations to make Victoria a more equal place.

Safe and strong put gender equality at the centre of decision-making in the public sector. It laid the groundwork for building gender equality into Victoria’s economy. It created tools for gender equality impact assessments for all policy and funding decisions. It also improved our knowledge and evidence base for gender equality measures, targets and outcomes.

Safe and strong supported local initiatives to drive gender equality in groups including migrant women, Aboriginal women, women in rural and remote areas, young women, older women and women with a disability.

The main achievements of Safe and strong were:

- passing the Gender Equality Act 2020

- creating the role of the Commissioner for Gender Equality in the Public Sector.

Timeline of gender equality reforms

Landmark Royal Commission into Family Violence

2016

Australia's first Royal Commission into Family Violence found that Victoria needs to address gender inequality to reduce family violence and all forms of violence against women.

Safe and strong released

2016

We released Victoria's inaugural gender equality strategy, Safe and strong. This led to landmark reforms to address the link between gender inequality and violence against women.

Inaugural Gender equality budget statement

2017

The Gender equality budget statement outlines a range of government initiatives advancing gender equality for all Victorians. It is now released every year.

Respect Victoria established

2018

Respect Victoria is the first agency of its kind in Australia. It is dedicated to the primary prevention of all forms of family violence and violence against women.

Gender equal Cabinet

2018

For the first time in Victoria's history, the Victorian Cabinet is 50% women.

Gender Equality Act 2020 passed

2020

The Gender Equality Act 2020 aims to improve workplace gender equality in the Victorian public sector, universities and local councils.

Gender Responsive Budgeting Unit established

2021

This is the first Gender Responsive Unit in Australia. The unit ensures that government decisions for budgets measure and consider gender impacts.

Inquiry into economic equity for Victorian women

2021

We established the independent Inquiry into economic equity for Victorian women. It developed recommendations for government to progress economic equity for Victorian women.

All 227 recommendations of the Royal Commission into Family Violence achieved

2023

A key milestone in the reform of Victoria’s nation-leading family violence system, strengthening its foundations and supporting all Victorians to feel confident about reporting family and sexual violence and seeking help.

Our equal state: Victoria’s gender equality strategy and action plan released

2023

The release of Victoria’s second gender equality strategy is the next marker in the generational change to achieve gender equality.

Gender inequality affects us all

Gender equality is not a ‘women’s issue’. The effects of gender inequality touch all parts of our community. Gender stereotypes have negative effects on people of all genders.

Women are worse off by almost every measure. Whether it’s the pay gap, time spent doing unpaid care, high rates of gendered violence, or not enough women in leadership and public spaces, it comes back to one thing. Gender inequality.

For gender diverse people, identifying, expressing and/or experiencing gender outside the traditional gender binary results in varied forms of discrimination, stigma and exclusion. This discrimination violates rights. It limits participation in society. It also leads to poorer health, economic and social outcomes for gender diverse Victorians.

For men and boys, pressure to conform to some stereotypes of masculinity can impact physical and emotional health. Such stereotypes include having to be tough, stoic, dominant and aggressive. Though girls and young women are more likely to suffer from mental health conditions, men are less likely to seek help for them. [1]

At work, gender stereotypes mean that men may feel less able to call-out outdated ideas or access flexible working policies and parental leave. In Australia, men are twice as likely as women to have flexible work requests denied. [2]

Rigid stereotypes of masculinity play a direct role in men’s violence against women and gender diverse people. We need to address harmful forms of masculinity to prevent gendered violence, as well as engage men and boys in gender equality.

A gender equal society benefits everyone. It makes our communities safer, healthier and more connected.

References

[1] L Clark and J Hudson et al., ‘Investigating the impact of masculinity on the relationship between anxiety specific mental health literacy and mental health help-seeking in adolescent males’, Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 2020, accessed 12 April 2023. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0887618520301067

[2] M Sanders, J Zeng, M Hellicar and K Fagg, ‘The power of flexibility: a key enabler to boost gender parity and employee engagement’, Bain & Company, 2016, accessed 6 February 2023. https://www.bain.com/insights/the-power-of-flexibility/

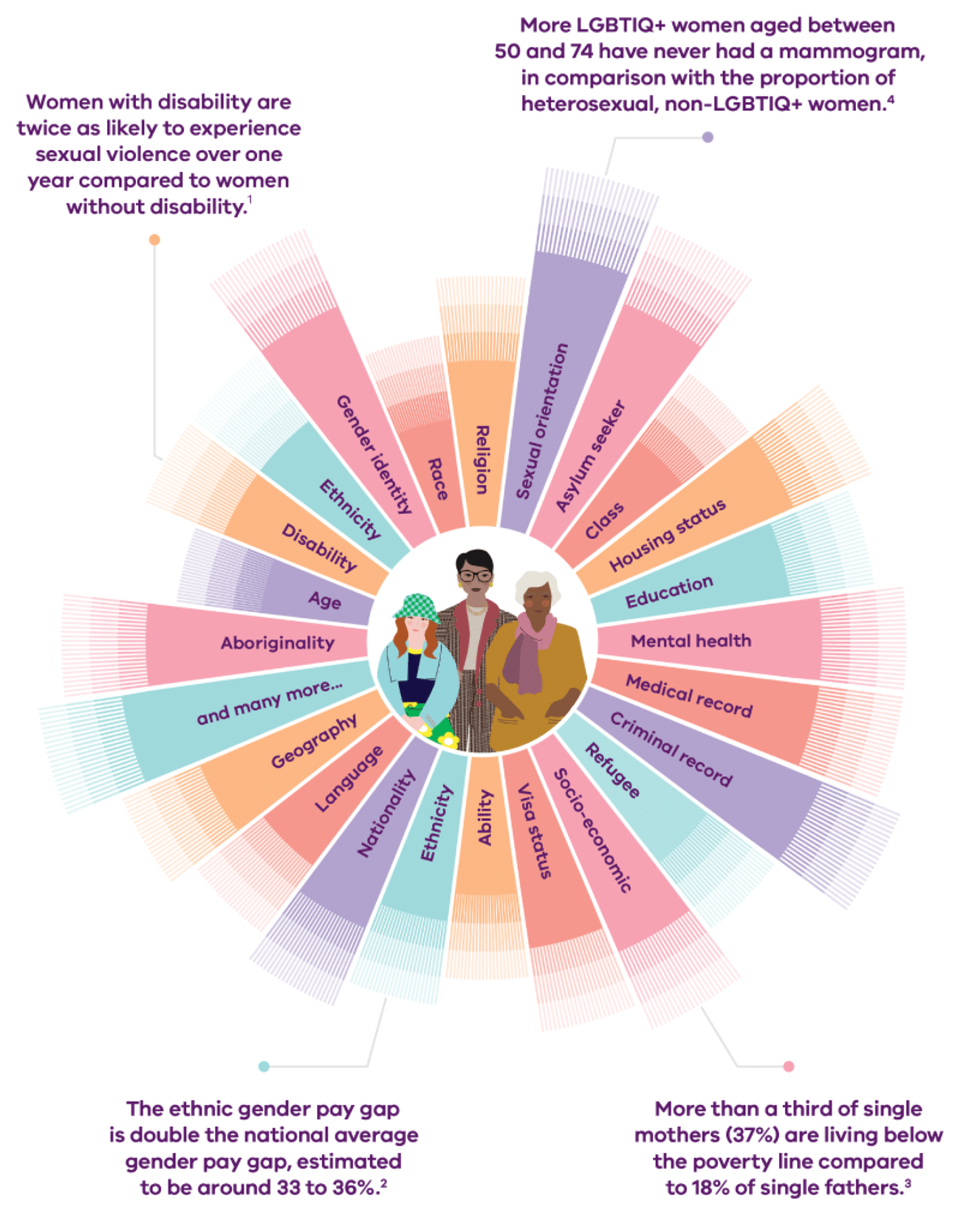

People experience gender inequality differently

Not everyone experiences gender inequality the same way. Gender inequality exists alongside other forms of disadvantage or discrimination based on identity. These include characteristics such as Aboriginality, age, disability, ethnicity, gender identity, race, religion, sexual characteristics, sexual orientation and other attributes.

Different parts of identity can expose people to many types of discrimination and marginalisation, and increase inequality and hardship.

Our equal state takes an intersectional approach to gender equality. In our work, we must:

- understand compounding inequalities

- define and collect better data and evidence

- listen to and learn from the lived experience of women, men, gender diverse people, families and communities.

We recognise that there is more work to do.

‘A truly gender equitable transformation of our society must be intersectional and see the whole person.’

– contributor via Engage Victoria

Explainer: what are gender norms and stereotypes?

Gender norms are society’s expectations and beliefs about how men, women and gender diverse people should behave. They shape attitudes and behaviours about gender. Gender norms are different from personal beliefs and actions.

Gender norms can create a continuous cycle of gender stereotyping. They can change over time as attitudes and beliefs evolve. They exist on an individual, relationship, community and societal level.

Rigid gender stereotypes and norms limit us all. They shape mentalities and how we see our role in society.

Australian men are more traditional in their gender attitudes than the global average, with 30% of Australian men agreeing gender inequality doesn’t really exist. [5]

28% of Australian men think women often make up or exaggerate claims of abuse or rape. [6]

In 2020-21, the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission received 403 complaints related to workplace and everyday sexism, sexual harassment and gender discrimination. This includes:

- 38 on the basis of pregnancy

- 63 on parental status

- 176 on the basis of sex

- 102 on the basis of sexual harassment

- 24 on the basis of gender identity. [7]

The 2023 National Community Attitudes Survey [8] showed that:

- 41% mistakenly believe that domestic violence is equally perpetrated by men and women

- an alarming proportion of Australians mistrust women’s reports of violence, with 34% believing that it is common for women to use sexual assault accusations to get back at men

- 41% believe that many women mistake innocent remarks as sexist.

References

[1] Royal Commission into violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation of people with disability 2021, Alarming rates of family, domestic and sexual violence of women and girls with disability to be examined in hearing, Royal Commission website, 2021, accessed 06 February 2023. https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/news-and-media/media-releases/alarming-rates-family-domestic-and-sexual-violence-women-and-girls-disability-be-examined-hearing

[2] R Whitson, ‘Culturally diverse women paid less, stuck in middle management longer and more likely to be harassed’, ABC, 12 March 2022, accessed 06 February 2023. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-03-12/why-cultural-diversity-matters-iwd/100899548

[3] Council of Single Mothers and their Children, ‘The feminisation of poverty: why we need to talk about single mothers’, CSMC, 2022, accessed 06 February 2023. https://www.csmc.org.au/2022/10/the-feminisation-of-poverty-why-we-need-to-talk-about-single-mothers/

[4] Victorian Agency for Health Information, The health and wellbeing of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer population in Victoria: Findings from the Victorian Population Health Survey, 2020, accessed 3 May 2023. https://vahi.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-12/The-health-and-wellbeing-of-the-LGBTIQ-population-in-Victoria.pdf

[5] The Global Institute for Women’s Leadership, International Women’s Day 2022, accessed 26 April 2023. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2022-03/Int…

[6] The Global Institute for Women’s Leadership, International Women’s Day 2022.

[7] Victorian Equal Opportunity & Human Rights Commission, 2020–2021 Annual report, VEOHRC, 2021, accessed 23 December 2022. https://www.humanrights.vic.gov.au/static/17e7f07a6011ef9bf0002454f5a65…

[8] Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety, Attitudes matter: Overall Australians attitudes towards violence against women have improved, but there is still a long way to go, ANROWS, 2023, accessed 26 April 2023. https://www.anrows.org.au/media-releases/attitudes-matter-ncas21-media-…

Gender inequality is a driver of violence against women

Gender inequality underlies family violence and violence against women. This violence continues to be a significant risk to the lives of Victorian women.

Our Watch’s Change the story points to 4 gendered drivers of violence:

- condoning of violence against women

- men’s control of decision-making and limits to women’s independence in public and private life

- rigid gender stereotyping and dominant forms of masculinity

- male peer relations and cultures of masculinity that emphasise aggression, dominance and control. [1]

Many other forms of inequality influence violence against women. These include racism, ableism, ageism, heteronormativity, cissexism, transphobia and class discrimination. Aboriginal women experience disproportionate risks due to the ongoing impacts of colonisation. Rigid gender norms, cisnormativity and heteronormativity are major factors in the abuse and violence experienced by LGBTIQ+ people. This includes both in their families of origin and in society more generally. [2]

Following the Royal Commission into Family Violence in 2016, we announced an ambitious plan: 10 years to rebuild Victoria’s family violence system. Eight years since the Royal Commission, we have achieved all 227 recommendations and have invested more than $3.7 billion to prevent and respond to family violence.

Yet, there is much more work to do to keep people safe, hold people to account and stop violence before it starts. Ending this violence requires generational change, and we remain unwavering in our resolve.

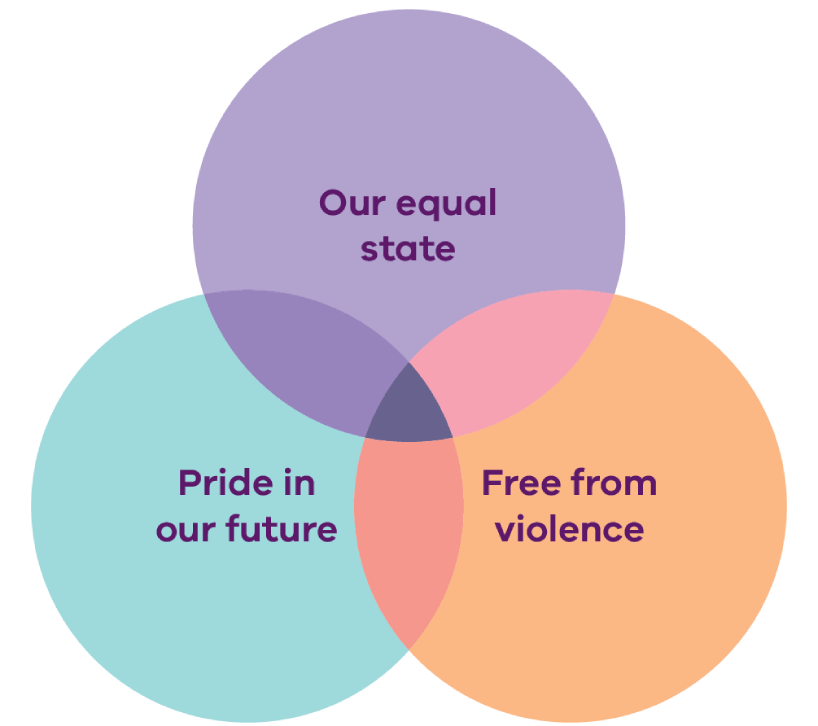

Free from violence: Victoria’s strategy to prevent family violence and all forms of violence against women aligns with and strengthens Our equal state. This includes a range of primary prevention initiatives to end violence before it happens by addressing the attitudes, values and behaviours that condone it. Promoting gender equality is a shared outcome for Our equal state and Free from violence.

Dhelk Dja is the key Aboriginal-led Victorian agreement that commits the signatories to work together and be accountable for ensuring that Aboriginal people, families and communities are stronger, safer, thriving and living free from family violence. Signatories include Aboriginal communities, Aboriginal services and government. The Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum will continue to lead Aboriginal-led prevention as a priority and champion this work with Aboriginal communities.

References

[1] Our Watch, Change the story: a shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women in Australia, Our Watch, 2021, accessed 12 April 2023. https://www.ourwatch.org.au/change-the-story/

[2] Rainbow Health Australia, Pride in prevention: a guide to primary prevention of family violence experienced by LGBTIQ communities, 2020, accessed 12 April 2023https://rainbowhealthaustralia.org.au/news/launch-pride-in-prevention-evidence-guide

Gender equality requires sustained, transformative and generational change

Women and gender diverse people have historically experienced discrimination and disadvantage on the basis of sex and gender. [1] Our equal state has a strong focus on improving outcomes for Victorian women, girls and gender diverse people.

Work to address gender inequality has tended to focus on building the capability of individuals without addressing unequal and discriminatory systems. This strategy aims to change that. It addresses gender discrimination and biases that affect all Victorians.

Importantly, this strategy aligns with Victoria’s first whole-of-government LGBTIQ+ strategy. Pride in our future: Victoria’s LGBTIQ+ strategy 2022–32 is the vision and plan to drive equality and inclusion for Victoria’s LGBTIQ+ communities.

This strategy is not intended to replace Pride in our future. The strategies work together for greater equality for all Victorians.

Figure 4. Strategies Our equal state works closely with to drive gender equality

References

[1] Deloitte Access Economics, Breaking the norm: unleashing Australia’s economic potential, 2022, accessed 06 February 2023. https://www2.deloitte.com/au/en/pages/economics/articles/breaking-norm-unleashing-australia-economic-potential.html

Childhood and youth

Our early years are the most important for learning and establishing the foundations for future wellbeing. It is also a time of significant change for young people – both physically and emotionally.

It is vital that all young Victorians’ experiences and opportunities are not limited by their gender. This includes in education, jobs and career pathways, community, recreation – including online spaces – and health and wellbeing.

We must challenge gender norms and biases

Gender norms, expectations and stereotypes have a profound impact on children and young people.

Improving sexual, reproductive and mental health outcomes for young Victorians

Childhood and adolescence are times of significant change and development. Adjusting to the physical and emotional changes of puberty can be challenging.

Young people deserve to be free from gendered violence

Many people witness gendered violence in their own families. Many also experience it in their own relationships.

It can be hard to be what you can’t see

Women’s contributions and achievements are underrepresented in the public domain.

We must challenge gender norms and biases

Gender norms, expectations and stereotypes have a profound impact on children and young people. We create and reinforce gender norms early in life through our families, communities, institutions, education and traditional and social media. Gender norms are also reinforced by advertising that shapes children’s social, educational and leisure choices.

Australia’s labour market is highly segregated by gender. Entrenched stereotypes about ‘male’ and ‘female’ careers influence students from a young age. For example, girls in Australia have lower science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) participation rates and lower STEM aspirations in school compared with boys. Women are often less likely to work in or study STEM after school. [1] This is also reflected in low rates of women in trades and technical roles. In a similar way, boys have lower participation rates in subjects such as textiles and food technology. Men are also less represented in jobs related to caring.

This strategy will develop and put in place an approach to address gender bias in careers education and pathways options for girls and gender diverse students by delivering the Senior Secondary Pathways Reforms.

We will also address gender bias in the workforce through training pathways. To achieve this, we will:

- further explore ways to embed gender equality across the VET and training sector

- bridge the gender gap with the Victorian Skills Plan

- remove financial barriers to training for women through Free TAFE.

We are working with traditionally 'male’ industries to remove barriers to attract and recruit young women and girls to these jobs. This includes through strategies to support, upskill and mentor women in the energy and manufacturing sectors.

Children are more likely to have primary carers who are women and see women do more unpaid work at home. This means we pass gender norms down to the next generation. We’ve heard from many men that they want more support to be the best fathers they can be. We will invest $2 million for the creation of more fathers’ groups across the state, providing more opportunities for fathers to feel supported and connected in a peer-to-peer setting.

Key statistics

- The gender pay gap starts with pocket money. Boys receive more pocket money on average than girls. [2]

- Only 22% of young women aged 18 to 24 are considered financially literate compared to 42% of young men the same age. [3]

References

[1] Deloitte Access Economics, Breaking the norm: unleashing Australia’s economic potential, 2022, accessed 06 February 2023. https://www2.deloitte.com/au/en/pages/economics/articles/breaking-norm-…

[2] Finder, Finder’s parenting report: a report on family trends and finances, 2021, accessed 06 February 2023. https://dvh1deh6tagwk.cloudfront.net/finder-au/wp-uploads/2021/09/Finde…

[3] L Walsh, C Waite et al., 2021 Australian youth barometer: understanding young people in Australia today, 2021, accessed 12 April 2023. https://researchmgt.monash.edu/ws/portalfiles/portal/363926354/36128898…

Improving sexual, reproductive and mental health outcomes for young Victorians

Childhood and adolescence are times of significant change and development. Adjusting to the physical and emotional changes of puberty can be challenging. Stigma and social pressure to hide any sign of menstruation can stop girls and young women from talking about their experiences, playing sport or seeking support and advice.

Key statistics 1

- Girls and young women are less likely to take part in sport as they get older. Almost 50% of girls drop out of sport by the age of 17. [1]

- Almost a third of Australian girls aged 10 to 14 miss school because they are embarrassed about their periods. [2]

We will continue to provide free pads and tampons in government schools. This will make it easier for students to manage their menstrual health, and allow them to fully engage in their education. We will also provide free pads and tampons in public spaces and investigate strategies to further destigmatise periods.

We will improve access to healthcare for young Victorians by establishing 9 new sexual and reproductive health hubs. This will expand the network to 20 hubs across the state.

Mental health conditions often emerge in adolescence. Around 75% of diagnosable mental illnesses first emerge before the age of 25. [3] Young women experience poor mental health at almost double the rates of young men. The risk of distress and mental health conditions can increase for young people who are same-sex attracted or questioning their sexuality or gender.

This strategy will deliver a funding package to expand access to vital mental health and support services for gender diverse Victorians.

Young Victorians have suffered a surge of eating disorders, a statistic that is sadly replicated worldwide. Eating disorders are the third most common chronic illness in young women and have the highest mortality rate of all psychiatric illnesses. This includes increased risk of suicide. [4]

Key statistics 2

- Body image is in the top 4 concerns for young Australians, with 30% concerned about their body image. [5] Up to 80% of young teenage girls report a fear of becoming ‘fat’. [6]

- Compared to the general population, LGBTIQ+ young people are at higher risk of major depression, generalised anxiety disorder, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. [7]

This strategy will support young Victorians with emerging mental health conditions to recover and live happy, healthy lives.

We are building Victoria’s mental health system from the ground up with a strong gender lens through our unprecedented investment following the findings of the Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System. This means we are thinking critically about how our policies, programs and services meet the different needs of women, men and gender diverse people so we can develop solutions that benefit everyone.

This is a collective effort. We are engaging the sector as we achieve the recommendations, including with services, not-for-profit organisations, the workforce and people with lived experience of mental health conditions.

Case study: helping schools promote positive menstrual health

Free pads and tampons are available in every government school in Victoria – because being able to access period products shouldn't be a barrier to students getting the most out of their education.

Victoria is the first state or territory in Australia to ensure every government school student has access to free period products. The $36.2 million initiative began in Term 3 in 2019 and we installed dispensing machines in every school by the end of Term 2, 2020.

A lack of easy access to pads and tampons can affect students participating in sports and everyday school activities. Students may not be able to concentrate in class, feel comfortable or confident doing physical activity or they may miss school altogether. By making pads and tampons available and free at school, we are one step closer to educational equality.

Schools have an important role to promote positive culture around menstrual health and build supportive environments. The initiative aims to reduce the stigma of periods and make school a more inclusive place where students can focus on their studies.

We will continue to normalise periods and provide cost-of-living relief through our $23 million package to provide free pads and tampons at up to 700 public locations across the state. They will be available in public hospitals, courts, TAFEs, public libraries, staffed train stations, and major cultural institutions like the State Library and Melbourne Museum in 2024.

References

[1] Suncorp, Suncorp Australian Youth & Confidence Research 2019, 2019, accessed 12 April 2023. https://www.suncorp.com.au/learn-about/teamgirls/teamgirls-powered-by-s…

[2] Plan International, One in five boys and young men think periods should be kept secret, media release, 2022, accessed 06 February 2022. https://www.plan.org.au/media-centre/one-in-five-boys-and-young-men-thi…

[3] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Australia’s youth: mental illness, 2021, accessed 20 March 2023. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/mental-illness

[4] Women's Health Victoria, Submission to the Royal Commission into Victoria's Mental Health System, WHV, 2019, accessed 06 February 2023. https://womenshealthvic.com.au/resources/WHV_Publications/Submission_20…

[5] E Carlisle, J Fildes, S Hall, V Hicking, B Perrens and J Plummer, Youth Survey Report 2018, Mission Australia, 2018.

[6] A Kearney‐Cooke, and D Tieger, ‘Body image disturbance and the development of eating disorders’ in L Smolak and MD Levine (eds), The Wiley handbook of eating disorders, Wiley, West Sussex, UK, 2015, pp 283–296.

[7] A Hill, A Lyons et al., Writing themselves in 4: the health and wellbeing of LGBTIQA+ young people in Australia, 2021, accessed 12 April 2023. https://www.latrobe.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/1198945/Writing-…

Young people deserve to be free from gendered violence

Many people witness gendered violence in their own families. Many also experience it in their own relationships.

Key statistics

- Young women (18 to 34 years) experience much higher rates of physical and sexual violence than women in older age groups. [1]

- Young women (18 to 29 years) with disability are at twice the risk of sexual violence than young women without disability. [2]

- Trans, non-binary and gender diverse young people experience high rates of gendered violence online and in public.

- In Australia, gendered and family violence remains a leading cause of homelessness for girls and young women. People under the age of 25 make up 37% of all people experiencing homelessness. [3]

- Two in 5 women aged between 18 and 29 years have been sexually harassed online or with some form of technology. [4]

Young women and gender diverse people are increasingly experiencing harassment and abuse in online spaces. Young women are more likely to witness online racism or hateful comments towards particular cultural or religious groups, receive unwanted comments about their appearance and be told not to speak or have an opinion. [5] [6]

We will keep supporting schools and early childhood settings to promote and model respectful attitudes and behaviours through the Respectful Relationships initiative. Respectful Relationships teaches our children how to build healthy relationships, resilience and confidence. Taking a whole-school approach works to embed a culture of respect and equality across an entire school community, from our classrooms to staffrooms, sporting fields, fetes and social events. This approach improves students’ academic outcomes, mental health, classroom behaviour and relationships with teachers.

We will also build on Free from violence to deliver programs for young people to prevent gendered violence, including education about affirmative consent.

We have changed the way we deal with sexual violence in Victoria. The Justice Legislation Amendment (Sexual Offences and Other Matters) Act 2022 includes amendments that will adopt an affirmative consent model and provide better protections for victim survivors of sexual offences. This will shift the scrutiny from victim survivors onto their perpetrators. The model will make it clear that everyone has a responsibility to get consent before engaging in sexual activity.

The Justice Legislation Amendment (Sexual Offences and Other Matters) Act 2022 also includes stronger laws to target image-based sexual abuse. This includes taking intimate videos of someone without their consent and distributing, or threatening to distribute, intimate images, including deepfake porn.

Case study: engaging boys and young men to prevent gendered violence

Rigid attachments to stereotypes of masculinity – such as aggression, dominance, control or hypersexuality – influence gendered violence. When we think of aggression and disrespect towards women as just being ‘one of the boys’, we are more likely to excuse violence towards women.

In 2023, we are supporting Jesuit Social Services to deliver an early intervention program with boys and young men aged 12 to 25 who are at risk of using violence against women. The program will:

- support conversations that challenge harmful masculinities

- promote more flexible ideas about what it means to be a man

- build the capacity of key workforces that engage with boys and young men to support them to live respectful, accountable and fulfilling lives.

We are funding this program through the National Partnership on Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence Responses. It is also a key program under Free from violence.

References

[1] Our Watch, Quick facts: violence against women, 2023, accessed 12 April 2023. https://www.ourwatch.org.au/quick-facts/

[2] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, People with Disability in Australia, AIHW, 2022, accessed 06 February 2023. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/disability/people-with-disability-in-au…

[3] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Estimating Homelessness: Census, ABS, 2023, accessed 20 April 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/housing/estimating-homelessnes…

[4] AHRC, Everyone’s business: fourth national survey on sexual harassment in workplaces, AHRC, 2018, accessed 11 July 2022. https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/publication/AHR…

[5] eSafety Commissioner, Young people’s experience with online hate, bullying and violence, 2023, accessed 12 April 2023. https://www.esafety.gov.au/research/young-people-social-cohesion/online…

[6] eSafety Commissioner, Know the facts about women online, accessed 20 March 2023. https://www.esafety.gov.au/women/know-facts-about-women-online

It can be hard to be what you can’t see

Key statistics

- Only 11 of the 582 statues in Melbourne depict real, named women. There are more statues of animals than named women. [1] [2]

Women’s contributions and achievements are underrepresented in the public domain. This perpetuates gender stereotypes and norms that put women in silent or support roles, or excludes them altogether. A lack of gender diverse role models can also reinforce stereotypical gender norms for children and young people. This makes gender equality more difficult for the next generation.

Through this strategy, we will promote women’s contributions and achievements in public. The Victorian Women’s Public Art Program was only the start. We want to see Victorians of all genders represented in street names and public places. We want to ensure that we recognise a diverse range of people in public programs, such as the Victorian Honour Roll of Women and the Change Our Game Ambassador Program. It is important that we represent women from multicultural and multifaith communities, of all ages, regional and rural locations, LGBTIQ+ communities, Aboriginal backgrounds and those with disability.

Case study: remembering Stella Young

Stella Young was a comedian, journalist and disability rights advocate. A statue honouring her is one of 6 artworks funded by our $1 million Victorian Women’s Public Art Program.

Remembering Stella Young is a life-size bronze statue in her hometown of Stawell. The statue aims to continue Stella’s legacy to educate and challenge the community on perceptions of disability, and to strive for ‘a world where disability is not the exception, but the norm’.

A collective of 4 artists with lived experience of disability brought the piece to life in the Northern Grampians Shire. Artists Sarah Barton, Fayen D’Evie, Jillian Pearce and Janice Florence, together with local sculptor Danny Fraser, collaborated with Stella’s parents Lynne and Greg Young, consulting on everything from the design, the location and interactive elements.

Accessibility and inclusivity are at the heart of its design. The statue sits on a circular slab at ground level and includes interactive elements such as motion-activated sensors that give audio descriptions of the statue, a braille plaque and QR codes so visitors can access online videos and audio components.

The Victorian Women’s Public Art Program makes women’s achievements more visible. The program places them on the public record, and celebrates and supports women artists, the arts and creative sectors.

Creating a permanent record of the excellence and leadership of Victorian women shows future generations of women and girls what is possible.

References

[1] A monument of one’s own, 2022, accessed 12 April 2023. https://www.amonumentofonesown.com

[2] This figure has been updated to reflect the statues of netballer Sharelle McMahon that was unveiled on 8 March 2023 and women’s rights campaigner Zelda D’Aprano that was unveiled on 29 May 2023.

Adulthood

By adulthood, gender inequalities are clear in almost every aspect of our lives.

Our equal state seeks to address gendered barriers so Victorians can reach their full potential at home, work and in the community.

Victorian women and gender diverse people deserve full access to appropriate and empowering healthcare

Gender is a core determinant of health. Women and gender diverse people often face barriers to accessing health services that relate to cost, distance, culturally appropriate practice and the services

We will continue to strive to end gendered violence

Women and gender diverse people are less safe than men in shared and public spaces.

Sharing and valuing care

Outdated stereotypes about the roles of men and women mean women do almost twice as much unpaid care work as men.

Making our workplaces safe and equal

Victoria’s Inquiry into economic equity for Victorian women found that that women are over-represented in the care and community sector.

Supporting women and gender diverse Victorians to reach their leadership potential in workplaces and the community

Women and gender diverse people are under-represented in all levels of leadership in Victoria.

A focus on equality for Aboriginal women

Victoria is the first jurisdiction in Australia to action all 3 elements of the Uluru Statement from the Heart: Voice. Treaty. Truth.

Victorian women and gender diverse people deserve full access to appropriate and empowering healthcare

Key statistics

- Approximately 200,000 women in Victoria suffer from endometriosis. [1] On average, it takes 7 years from the beginning of symptoms to receiving a diagnosis. This leaves women suffering pain that significantly affects their lives and choices. [2]

- Women are much less likely to play sport. Only 15.1% of women and girls aged 15 and over in Victoria take part in sport activities 3 times per week. For Victorian men and boys of the same age, it is 26.5%. [3]

- Pregnancy poses an increased mental health risk for women. Almost 1 in 5 women experience a mental health condition during pregnancy. [4]

Gender is a core determinant of health. Women and gender diverse people often face barriers to accessing health services that relate to cost, distance, culturally appropriate practice and the services that are available. Aboriginal women experience these barriers more, as do women living with a disability, migrant and multicultural women, women in regional and rural areas and LGBTIQ+ communities. Many people also do not get the care they need because some services lack cultural safety, sensitivity and responsiveness.

We will deliver a comprehensive package that ensures all women and gender diverse people can access the dedicated health services they need – no matter where they live or how much they earn. Victoria has always been a leader in providing safe, supportive and judgment-free healthcare, putting patients and their needs at the centre of every medical decision. But we know there’s more work to do.

Reproductive system conditions and issues can be barriers to good sexual and reproductive health, and general health and wellbeing. Such issues include menstruation, fertility, polycystic ovary syndrome, endometriosis, pelvic pain, contraception and sexually transmissible infections. Menopause has a big impact on the lives of women. This is because of stigma, lack of research and information, and lack of adequate and appropriate health care.

We recognise these are specialist areas that need expert attention. This strategy has significant actions to achieve this, including:

- to establish women’s health clinics

- a Women’s Health Research Institute

- the expansion of services for endometriosis and sexual and reproductive health care.

Systemic and unconscious biases mean women’s pain is often not taken seriously or treated properly. This leads to delays in diagnosis and care. Women report more severe levels of pain, more often and for longer durations. Despite this, women receive less treatment for pain than men. Diseases that mainly affect women and that have different symptoms to men do not receive the same levels of study or treatment. They are also often misdiagnosed or undiagnosed. For example, heart attack symptoms in women are less recognised than in men. We are establishing an inquiry into women’s pain management to examine these systemic issues and find solutions.

Healthcare service workers also need training to ensure they are safe, inclusive and affirming for gender diverse communities. Through Our equal state, we will support 200 community and mental health service providers to become Rainbow Tick accredited to ensure safer and more inclusive care for LGBTIQ+ Victorians.

Case study: giving women’s health the focus and funding it deserves

We are working to deliver a comprehensive package to reform and expand women’s health services across the state.

We will create 20 new women's health clinics to give women access to specialist multidisciplinary assessment and treatment for conditions such as endometriosis and pelvic pain. A new mobile women’s health clinic will also visit remote parts of the state, and we are working with Aboriginal health organisations to deliver an extra dedicated Aboriginal-led women’s health clinic.

We will add 9 new locations to our network of women’s sexual and reproductive health hubs. This will give more women access to closer to home services and advice on contraception, pregnancy termination, and sexual health testing and treatment.

We will increase the number of surgeries for endometriosis and associated conditions, with an estimated 10,800 extra laparoscopies over the next 4 years. We are providing $2 million for scholarships to upskill the workforce with 100 more women’s healthcare specialists.

Working in partnership with the Australian Government, we will invest $5 million to support the creation of a Women’s Health Research Institute. This will help address the gender gap in medical research, where conditions unique to women don’t get enough funding and women aren’t meaningfully included in clinical trials.

We will also undertake an inquiry into women’s pain management, to examine systemic issues and find solutions. A panel of experts will chair the inquiry. They will review data and information and hear directly from women from different backgrounds on their experience accessing treatment.

Planning is under way on each phase of these reforms, and we will continue to work with the health sector and community, making sure Victorian women get the highest quality care.

References

[1] Better Health Channel, Women's reproductive health: where to find reliable information and services, 2023, accessed 12 April 2023. https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/healthyliving/womens-sexual-reproductive-health-info-services

[2] KE Nnoaham, L Hummelshoj, P Webster et al., Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries, 2011. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21718982/

[3] Australian Sports Commission, AusPlay Data Portal, 2021–22, accessed 16 May 2023. https://www.clearinghouseforsport.gov.au/research/ausplay/results.

[4] Perinatal Anxiety and Depression Australia, Mental health and wellbeing during pregnancy, accessed 17 May 2023. https://panda.org.au/articles/mental-health-and-wellbeing-during-pregnancy/

We will continue to strive to end gendered violence

Gender inequality drives violence against women. Victoria’s Royal Commission into Family Violence – the first of its kind in Australia – found that gender inequality must be addressed to reduce family violence and all forms of violence against women.

Key statistics 1

- On average, one woman a week is murdered by her current or former partner. [1]

- Violence in intimate relationships adds more to the disease burden for women aged 18 to 44 years than any other risk factor. Even more than smoking and alcohol use. [2]

- More than 60% of Victorian women have experienced some type of gendered violence and have felt at risk at work. [3]

Women and gender diverse people are less safe than men in shared and public spaces. Street-based harassment and assault is largely experienced by women and gender diverse people. Many women and gender diverse people worry about harassment and assault during transport journeys, especially at night.

Women and gender diverse people are much more likely to have experienced sexual harassment at work. Yet, it is underreported and perpetrators are rarely identified.

Some groups of women are disproportionately targets of gendered violence. This includes women with a disability, from multicultural and multifaith communities, and Aboriginal women.

Gendered violence can have long-term and serious negative impacts on victim survivors. These include:

- worse physical and mental health

- loss of or limited employment

- loss of housing

- less financial security

- isolation

- less social support

- loss of life.

This strategy challenges the attitudes, behaviours, cultures and systems that drive gendered violence. We will work to improve the safety of public transport and public spaces, and design them with the needs of women and gender diverse people in mind.

We will continue to work to prevent and better respond to sexual harassment at work. We will do this by working to restrict the use of non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) for workplace sexual harassment cases in Victoria. The Gender Equality Act 2020 and recommendations of the Ministerial Taskforce on Sexual Harassment will inform this work.

We will ensure workplaces treat sexual harassment as an occupational health and safety (OHS) issue. We will also increase WorkSafe’s capacity to take a lead role in preventing, and responding to, workplace sexual harassment (including through its existing OHS enforcement functions). This strategy will deliver the WorkWell Respect Fund and the WorkWell Respect Network. They will support employers to prevent work-related gendered violence, including sexual harassment in Victorian workplaces. We will also continue to enact Respect and Equality in TAFE to strengthen the TAFE network’s approach to gender equality and preventing gender-based violence.

This strategy challenges the attitudes, behaviours, cultures and systems that drive gendered violence. We will continue to deliver Free from violence: Victoria’s strategy to prevent family violence and all forms of violence against women. We will also continue to show leadership and advocate for collective action at a national level through the Australian Government’s National plan to end violence against women and children.

Key statistics 2

- Aboriginal women reported experiencing gendered violence at twice the rate of non-Aboriginal women. [4]

- Aboriginal women are 32 times more likely to be hospitalised due to family violence. Aboriginal women are also 11 times more likely to die from assault, compared to non-Aboriginal women. [5]

- Women are often the primary targets for online and public racist attacks. [6] Women experienced 82% of the Islamophobic attacks reported to the Islamophobia Register Australia in a 2019 study. [7] Women also experienced 60.1% of the 541 reports of racism made to the Asian-Australian Alliance between April 2020 and June 2021. [8]

- Women with disability are twice as likely to experience sexual violence over one year compared to women without disability. [9]

- People with an intersex variation were also more likely than those without such a variation to have been sexually harassed in their workplace in the last 5 years (77% compared to 32%). [10]

Case study: Respect Starts With A Conversation

Gender inequality enables the underlying conditions for violence against women and family violence to occur. Public campaigns can help encourage cultural change by raising awareness about the effects of gender inequality and challenging harmful attitudes and behaviours. Behaviour change campaigns are also a key action of Free from violence.

We supported Respect Victoria to create Respect Starts With A Conversation. It is a suite of videos that encourage people to reflect on what respect means to them, and to take action to promote respectful behaviours in their own lives and communities.

The videos feature everyday Victorians and aim to help Victorians understand how rigid gender stereotypes and dominant types of masculinity exist across homes, communities and workplaces.

Kobe and Mufaro’s video encourages viewers to reflect on their personal attitudes towards gender and relationships, and to promote respectful behaviour in their own lives. They speak about what it means to be a man, the role that respect plays in relationships and how breaking down unhelpful stereotypes about gender benefits both men and women.

‘The power of speaking up has way more impact than not saying anything.’

— Kobe

‘And so, as we are redefining what it is to be masculine and having vulnerability as an option, the way that it's impacted relationships with others is they've felt so much closer with the people around them.’

— Mufaro

The campaign has also appeared in cinemas, online and on billboards and radio across Victoria. Choosing to lead with respect in our relationships, workplaces, schools, universities and homes can ultimately prevent family violence and violence against women. Calling out discriminatory or disrespectful behaviour starts with every one of us.

References

[1] Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety, Violence against women: accurate use of key statistics, ANROWS, 2018, accessed 12 April 2023. https://www.anrows.org.au/resources/fact-sheet-violence-against-women-accurate-use-of-key-statistics/

[2] K Webster, A preventable burden: measuring and addressing the prevalence and health impacts of intimate partner violence in Australian women. Key findings and future directions, ANROWS, 2016, accessed 06 February 2023. https://www.anrows.org.au/publication/a-preventable-burden-measuring-and-addressing-the-prevalence-and-health-impacts-of-intimate-partner-violence-in-australian-women-key-findings-and-future-directions

[3] Victoria Trades Hall Council, Stop gendered violence at work: women’s rights at work report, VTHC, accessed 06 February 2023. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/victorianunions/pages/2370/attachments/original/1479964725/Stop_GV_At_Work_Report.pdf?1479964725

[4] Our Watch, Change the story: a shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women in Australia.

[5] Australian Human Rights Commission, Wiyi Yani U Thangani: Securing our rights, securing our future report, AHRC, 2020, accessed 12 April 2023. https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-social-justice/publications/wiyi-yani-u-thangani

[6] M Peucker et al., ‘All in this together: a community-led response to racism for the City of Wyndham’, in D Iner (ed), Islamophobia in Australia Report III (2018–2019), Charles Sturt University, Sydney, 2022. https://researchoutput.csu.edu.au/

[7] D Iner (ed), Islamophobia in Australia Report III (2018–2019).

[8] A Kamp et al., Asian Australians’ experiences of racism during the COVID-19 pandemic, Centre for Resilient and Inclusive Societies, Deakin University, 2021.

[9] Royal Commission into violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation of people with disability 2021, Alarming rates of family, domestic and sexual violence of women and girls with disability to be examined in hearing, Royal Commission website, 2021, accessed 06 February 2023. https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/news-and-media/media-releases/alarming-rates-family-domestic-and-sexual-violence-women-and-girls-disability-be-examined-hearing

[10] Respect@Work, LGBTIQ+ people, accessed 30 April 2023. https://www.respectatwork.gov.au/organisation/prevention/organisational-culture/diversity-and-inclusion/lgbtiq-people

Sharing and valuing care

Outdated stereotypes about the roles of men and women mean women do almost twice as much unpaid care work as men. [1] This includes looking after children, elderly parents and people with disability or long-term health conditions. This care work is so important to our society but is often undervalued and unrecognised. Women shoulder the financial burden, as well as associated health and wellbeing impacts.

Key statistics 1

- Victoria’s gender pay gap is currently 13.4%. [2] In Australia, the gender pay gap increases as workers age. It is 30.2% for employees aged 45 to 54 and reaches 31.9% for employees aged 55 to 64. [3]

- The ethnic gender pay gap is double the national average gender pay gap, estimated to be around 33 to 36%. [4]

- Women with disability are less likely to be in paid employment. They also receive lower incomes than men with disability and women without disability. [5]

In heterosexual couples where both partners have similar hours of paid work, there is still a large gap in unpaid work hours. This affects financial security and independence. In the long term it leads to lower lifetime earnings and superannuation for women. While more men now stay at home as primary carers for their children than ever before, women are still mostly responsible for caring for children.

Key statistics 2

- Women can experience motherhood penalty, with earnings falling by an average of 55% in the first 5 years of parenthood. [6] Motherhood penalty occurs mostly because women take time out of the workforce or work fewer hours after having a child.

- More than a third of single mothers (37%) are living below the poverty line compared to 18% of single fathers. [7]

- In 2018–19, 48% of Australian women mentioned ‘caring for children’ as the main reason they couldn’t start a new job or work more hours, compared to only 3% of men. [8]

- Almost 8 in 10 parental leave takers in the Victorian public sector are women. On average, women’s parental leave lasts 8 times longer than men’s. [9]

We will work to remove barriers which prevent women taking part in the workforce, including rebalancing the load of unpaid work and care. We will also promote and work to increase the value placed on care in our society.

We will invest $14 billion in the Best Start, Best Life reforms over the next decade to save families money and support women to return to work. The childcare system has been set up to work against working families – particularly mothers – who face barriers by the lack of affordable care options.

We will advocate to the Australian Government on the adequacy of carer payments and payment of superannuation on government-funded parental leave. We are addressing this in our public sector workforce through extending superannuation payments on paid parental leave to 52 weeks for teachers in Victorian public schools – our largest public sector workforce – and introducing a target to double the number of men taking available paid parental leave in the Victorian public sector to work towards rebalancing the gendered uptake of caring entitlements.

Through the Outside School Hours Care Establishment Grants Initiative, we are supporting more than 400 schools in Victoria to provide outside hours school care services. The aim is to reduce barriers to women taking part in the workforce, so parents and carers can get back into the workforce, study or training. This program provides schools with funding to establish new services or expand existing ones to help them meet demand for their outside school hours care service. Special schools and those in remote locations will receive more funding if needed.

Case study: Best Start, Best Life

Our Best Start, Best Life reforms will invest $14 billion over the next decade to make kindergarten programs more accessible and affordable.

Evidence shows that 2 years of quality early childhood education has more impact than one year and can lift children’s learning outcomes. The skills developed in early childhood also contribute to broader and longer-term outcomes. These include better employment prospects, health and wellbeing, and more positive social outcomes.

Families in Victoria will have access to 15 hours of funded, teacher-led 3-year-old kindergarten by 2029, and by 2032, 4-year-old kindergarten will transition to ‘Pre-prep’ – increasing to a universal, 30-hour-a-week program of play-based learning. We are also establishing 50 Victorian Government-owned, affordable early learning centres in areas that need more childcare.

As well as improving children’s lives, quality teacher-led kindergarten programs will also improve parent and carer participation in the workforce. This will have significant socio-economic benefits for families and children. It will also improve women’s economic independence and security, because the primary carer role is still carried out more by women than men in Victoria.

Independent analysis from Deloitte shows Best Start, Best Life will support between 9,100 and 14,200 extra primary carers to take part in the labour force by 2032–33, and increase total hours worked by primary carers by between 8 and 11%. [10]

With 94% of primary carers being women, this increase will overwhelmingly benefit female-dominated sectors that are all currently facing skills shortages like education, health services and hospitality.

References

[1] Workplace Gender Equality Agency, Removing the motherhood penalty, WGEA, 2018, accessed 11 November 2021. https://www.wgea.gov.au/newsroom/removing-the-motherhood-penalty

[2] Workplace Gender Equality Agency, Gender pay gap data, WGEA, accessed 3 May 2023. https://www.wgea.gov.au/pay-and-gender/gender-pay-gap-data

[3] Workplace Gender Equality Agency, Wages and ages: mapping the gender pay gap by age, WGEA, accessed 27 February 2023. https://www.wgea.gov.au/publications/wages-and-ages

[4] R Whitson, ‘Culturally diverse women paid less, stuck in middle management longer and more likely to be harassed’, ABC, 12 March 2022, accessed 06 February 2023. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-03-12/why-cultural-diversity-matters-iwd/100899548

[5] Victorian Government, Safe and strong: a Victorian gender equality strategy, 2016, accessed 06 February 2023. https://www.vic.gov.au/safe-and-strong-victorian-gender-equality

[6] Australian Treasury, Children and the gender earnings gaps, Australian Treasury, 2022, accessed 06 February 2023. https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-11/p2022-325290-children.pdf

[7] Council of Single Mothers and their Children, ‘The feminisation of poverty: why we need to talk about single mothers’, CSMC, 2022, accessed 06 February 2023. https://www.csmc.org.au/2022/10/the-feminisation-of-poverty-why-we-need-to-talk-about-single-mothers/

[8] Australia Bureau of Statistics, Barriers and incentives to labour force participation, ABS, 2022, accessed 12 April 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/barriers-and-incentives-labour-force-participation-australia/latest-release

[9] Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector, Baseline report – 2021 workplace gender audit data analysis, 2022, accessed 12 April 2023. https://content.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-12/Baseline-report-2021-workplace-gender-audit-data-analysis.pdf

[10] Premier of Victoria, ‘Best start, best life means billions for Victoria’s economy’, media release, 1 September 2022. https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/best-start-best-life-means-billions-victorias-economy

Making our workplaces safe and equal

Victoria’s Inquiry into economic equity for Victorian women found that that women are over-represented in the care and community sector, driven by gender norms around the kinds of work women and men should perform.

Pay in the care and community sector is low and is not equal with the value it creates socially and economically. Low pay in this sector is also driven by the assumption that caring is innate rather than a learnt skill. The care and community sectors have high rates of insecure, casual and part-time work.

Key statistics

- There are many women from multicultural and multifaith backgrounds in insecure and low-paid work. They make up a significant amount of Australia’s direct care workforce, including nurses, allied health workers, and personal and community care workers. [1]

- 77.7% of trans and gender diverse Victorians have faced unfair treatment at work based on their gender identity. [2]

In contrast, men are over-represented in industries with better job security and pay. These include construction, transport and mining. Structural barriers – including gender bias and discrimination, sexism and sexual harassment, and inflexible work arrangements that don’t accommodate care responsibilities – discourage women from training and working in these sectors. Lack of access to paid parental leave makes this worse.

Discrimination on the basis of sex and gender identity, as well as race, age, disability, religion and sexual orientation all intersect to limit equality in the workforce. This affects a person’s financial security, health and wellbeing. Women with a disability also face major barriers due to bias, discrimination, a lack of accessible workplaces and access to reasonable adjustments.

Through Our equal state, we will:

- identify and reduce structural barriers to the labour market

- reduce gender segregation and harmful work practices that affect Victorians of all genders

- get more women into safe and meaningful jobs in the construction, transport, energy and manufacturing industries

- get more men into our care industries

- support all groups of women falling through the cracks of our systems by investing directly in economic security programs that help women locked out of work

- explore ways to improve public sector gender equality through public sector industrial relations negotiations.

References

[1] C Eastman, S Charlesworth and E Hill, Markets, migration and the work of care. Fact sheet 1: migrant workers in frontline care, 2018, accessed 12 April 2023. https://www.arts.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/documents/Migrant%20Workers%20in%20Frontline%20Care.pdf; Gender Equity Victoria, Left behind: migrant and refugee women’s experience of COVID-19, 2021, accessed 12 April 2023. https://www.genvic.org.au/focus-areas/genderequalhealth/left-behind-migrant-and-refugee-womens-experiences-of-covid-19/

[2] AO Hill, A Bourne, R McNair, M Carman and A Lyons, Private Lives 3. The health and wellbeing of LGBTQ people in Victoria: Victoria summary report, 2021, accessed 3 May 2023. https://www.latrobe.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/1229468/Private-Lives-3-The-health-and-wellbeing-of-LGBTQ-people-in-Victoria.pdf

Supporting women and gender diverse Victorians to reach their leadership potential in workplaces and the community

Women and gender diverse people are under-represented in all levels of leadership in Victoria. The main reasons for this are:

- the challenges of balancing work and care responsibilities

- a lack of flexibility in senior positions

- unsafe and unwelcoming workplace cultures.

Barriers to leadership positions are harder for some women, who face discrimination because of attributes such as race, gender identity, sexual orientation and disability.

Key statistics

- Women are under-represented in leadership positions. Culturally diverse women even more so. Only 5.7% of culturally diverse women were board directors in 2022. [1]

- In the Victorian public sector, women make up 66% of the workforce, but only 46% of leadership roles. There is a very small number of people of self-described gender in senior leadership positions. [2]

Parental leave and part-time work negatively affect women’s opportunities to work in management roles or get promoted. In contrast, men’s career prospects are largely unaffected by the birth of a child. In fact, it can often improve due to stereotypes around fathers as breadwinners. [3]