Indicator: Increase workforce diversity

Measure: Number/proportion of workforce who identify as from a priority community – ATSI, CALD, LGBTIQ+, disability

The Royal Commission highlighted the lack of detailed knowledge and essential workforce data about family violence workers in Victoria.

To address this gap, we undertake the family violence workforce census every two years. The census collects data and information about family violence workforces.

The following indicators and measures use the survey results from the 2019–20 census. Subsequent results will be compared with these to identify any progress made.

In 2019–20, most family violence workers identified as female (85–87 per cent), with 1 per cent identifying as non-binary (self-described).

Between 7 per cent and 13 per cent of the specialist family violence response and primary prevention workforces are classified as having a disability. This means they experience difficulties or restrictions which affect their participation in work activities.

Between 3–4 per cent of workers identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander.

Between 6–7 per cent of workers spoke languages other than English at home.

Family violence workforce diversity 2019–20: specialist family violence response workforce

| Priority community | Number of responses | Total responses to questions | Proportion of workforce responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander | 41 | 1,357 | 3% |

| Person with a disability (This refers to people who experience difficulties or restrictions which affect their participation in work activities) | 94 | 1,366 | 7% |

| Speaks a language other than English at home | 97 | 1,384 | 7% |

| Uses their culture or faith-based knowledge and experience in undertaking their work | 478 | 1,196 | 40% |

| Born outside of Australia | 273 | 1,363 | 20% |

| Self-described gender | 14 | 1,374 | 1% |

| Age 55-74 | 278 | 1,391 | 20% |

Source: Family Violence Workforce Census 2019–20

Family violence workforce diversity 2019–20: primary prevention workforce

| Priority community | Number of responses | Total responses to questions | Proportion of responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander | 17 | 435 | 4% |

| Person with a disability (This refers to people who experience difficulties or restrictions which affect their participation in work activities) | 56 | 429 | 13% |

| Speaks a language other than English at home | 26 | 437 | 6% |

| Uses their culture or faith-based knowledge and experience in undertaking their work | 135 | 387 | 35% |

| Born outside of Australia | 86 | 431 | 20% |

| Self-described gender | 4 | 438 | 1% |

| Age 55-74 | 107 | 445 | 24% |

Source: Family Violence Workforce Census 2019–20

Indicator: Increase workforce skills and capabilities

Measure: Number/proportion of workforce who report confidence they have enough training and experience to perform their role effectively

Many workforces that intersect with family violence – including in mainstream and universal services – require training to build the family violence prevention and response capability across the system.

We have heard through our engagement with family violence practitioners that there is a strong association between receiving training in family violence or primary prevention and feeling confident to identify and respond to those experiencing family violence.1

Accordingly, this training is fundamental to the success of the family violence reforms, particularly The Orange Door, the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme and the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) framework.

In the 2019–20 Family Violence Workforce Census, at least half of the family violence workforce (61 per cent for specialist family violence response and 50 per cent for primary prevention) felt very to extremely confident in their level of training and experience to complete their role.

The survey identified that confidence rose with age and years of experience.

The top-two identified areas for additional support required to increase confidence for both cohorts were:

- further information sharing and collaboration with other service providers

- a community of practice for each cohort.

Family violence workforce confidence in level of training and experience 2019–20: specialist family violence response workforce (total responses 1,486)

| Confidence rating | Number of responses | Proportion of responses |

|---|---|---|

| Extremely confident | 178 | 12% |

| Very confident | 728 | 49% |

| Moderately confident | 446 | 30% |

| Slightly confident | 104 | 7% |

| Not confident | 15 | 1% |

Source: Family Violence Workforce Census, 2019–20

Family violence workforce confidence in level of training and experience 2019–20: primary prevention workforce (total responses 463)

| Confidence rating | Number of responses | Proportion of responses |

|---|---|---|

| Extremely confident | 60 | 13% |

| Very confident | 171 | 37% |

| Moderately confident | 171 | 37% |

| Slightly confident | 46 | 10% |

| Not confident | 19 | 4% |

Source: Family Violence Workforce Census, 2019–20

Indicator: Increase in health, safety and wellbeing of the family violence workforce

Measure: Number/proportion of workforce who report work-related stress

Work-related stress can lead to burnout (prolonged physical and psychological exhaustion).

This affects workers in ways including:

- physical and emotional stress

- low job satisfaction

- feeling frustrated by or judgemental of clients

- feeling under pressure, powerless and overwhelmed

- frequent sick or mental health days

- irritability and anger.

Family violence workforce work-related stress 2019–20: specialist family violence response workforce

| Work-related stress level | Number of workers | Proportion of workforce responses |

|---|---|---|

| None | 14 | 1% |

| Low | 303 | 21% |

| Moderate | 649 | 45% |

| High | 332 | 23% |

| Very high | 116 | 8% |

| Severe | 29 | 2% |

| Total | 1,443 | 100% |

| Feels safe performing role | Number of workers | Proportion of workforce responses |

|---|---|---|

| Always or often | 1,213 | 85% |

| Sometimes or less often | 214 | 15% |

| Total | 1,427 | 100% |

Source: Family Violence Workforce Census, 2019-20

Family violence workforce work-related stress 2019–20: primary prevention workforce

| Work-related stress level | Number of workers | Proportion of workforce responses |

|---|---|---|

| None | 5 | 1% |

| Low | 105 | 23% |

| Moderate | 206 | 45% |

| High | 92 | 20% |

| Very high | 41 | 9% |

| Severe | 9 | 2% |

| Total | 458 | 100% |

| Feels safe performing role | Number of workers | Proportion of workforce responses |

|---|---|---|

| Always or often | 397 | 88% |

| Sometimes or less often | 54 | 12% |

| Total | 451 | 100% |

Source: Family Violence Workforce Census, 2019-20

Most workers in both the specialist family violence response and primary prevention workforces experience at least moderate stress, with approximately one-third experiencing at least high levels of stress.

High workload is the key driver of high, very high and severe levels of stress in these workforces. Half the cohort reports that they only sometimes have sufficient time to complete tasks.

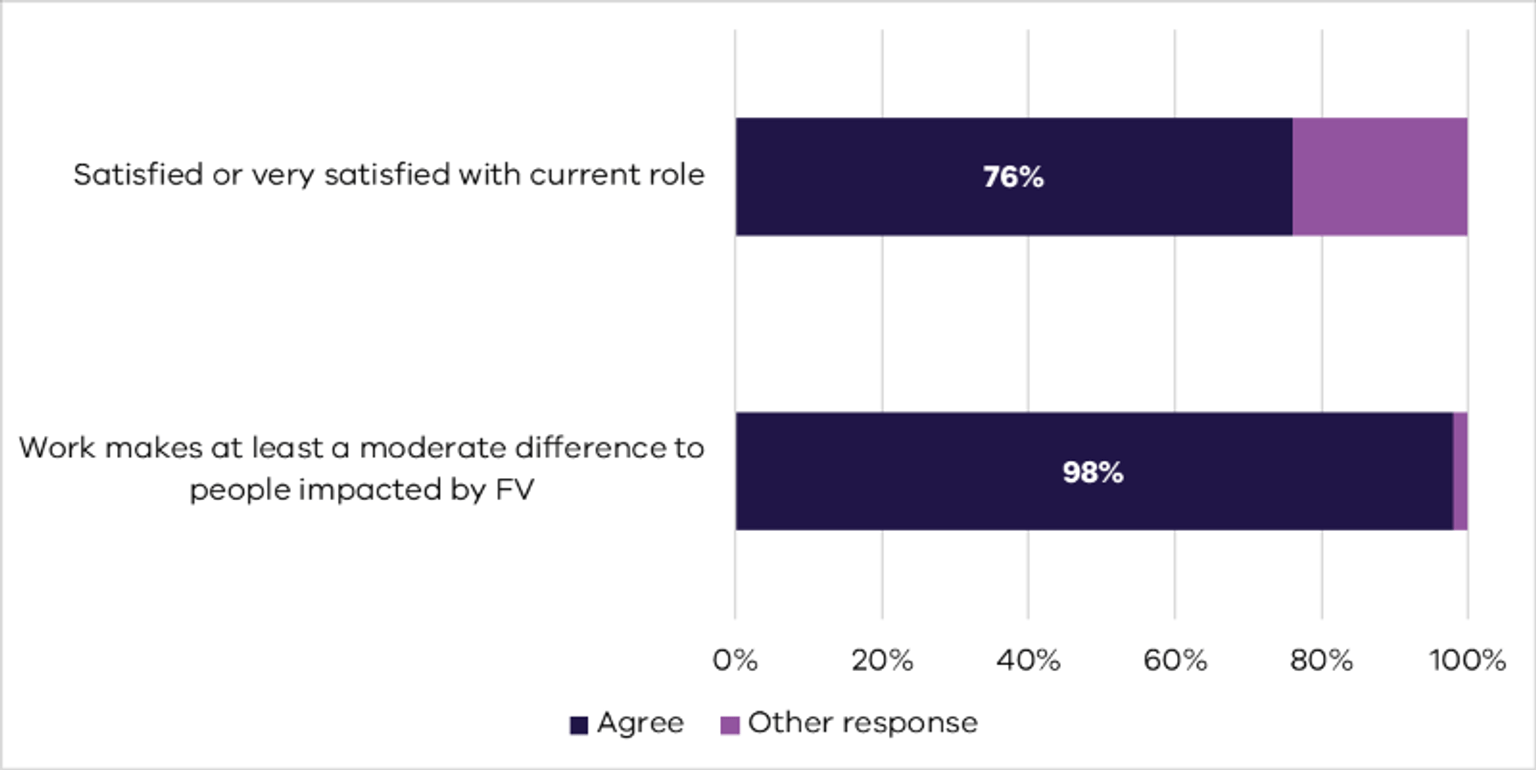

Positively, over 75 per cent are satisfied to very satisfied with their current role. Nearly all workers felt their work made a moderate to significant difference to people affected by family violence.

Notes

1Family Safety Victoria 2019, Building from strength: 10-year industry plan for family violence prevention and response, State Government of Victoria, Melbourne.

Updated