The following research questions are addressed in this chapter in considering the extent to which the CIS Scheme is achieving its intended outcomes:

To what extent has the CIS Scheme impacted the level and nature of relevant information sharing between prescribed information sharing entities?

In the context of the expectation that improved child information sharing supports better planning, service collaboration and earlier intervention.

To what extent has there been a positive impact on service provision in support of child wellbeing or safety?

In the context of the expectation that ISEs are enabled to identify and respond more appropriately to the wellbeing and safety needs of children through improved access to and quality of shared child information.

Box 5.1 Key findings – achievement of outcomes

Responding to a request to share information

- Among prescribed workforces, fewer perceive that there are legal restrictions or organisational policies that impede sharing information with other organisations or requesting information from other organisations.

- Prescribed workforces were less likely to refuse a request for information. Where there were refusals to share information, a clear reason for refusal was more likely to be provided than prior to the CIS Scheme.

- Privacy was significantly less likely to be a reason for refusing a request for information but was still likely to be a factor when workforce survey respondents’ requests for information were refused.

Information sharing activity

- Information sharing activity appears to have remained mostly the same since commencement of the CIS Scheme based on the results of the surveys of prescribed workforces, with some evidence pointing to a slight decline in the level of activity. Other evidence suggests that during the coronavirus pandemic there may be specific forms of information sharing activity that have increased while others have decreased.

Information sharing behaviour

- There appears to be some evidence for cultural shift towards early identification of supports for children, with some prescribed workforces appearing to have lower thresholds for seeking information.

- Prescribed workforces also appear to be considering a wider range of information sources when doing case planning for children.

- There is increased evidence of collaboration and coordination between sectors at various levels, including between peak bodies, individual services, and individual workers.

Embedding reforms

- Continued support and education is required to build on early signs of positive outcomes to ensure that these reforms are firmly embedded among information sharing entities.

Source: ACIL Allen Consulting 2020

5.1 Early identification and intervention to promote child wellbeing

5.1.1 Frequency of information sharing, and reasons for refusals to share information

Workforces from prescribed organisations and services were asked to reflect on the level of information sharing activity within their organisation in the 12 month period prior to and after commencement of the CIS Scheme.

The proportion of workforce respondents indicating that they had shared information (information going out) decreased marginally from 86% in the period before commencement of the Scheme to 83% following introduction of the Scheme with no change reported in the frequency of information sharing with other agencies following introduction of the CIS Scheme. Similarly, the proportion of workforces indicating that they had made requests for information remained the same at 70% both before and after introduction of the CIS Scheme, with a small decline indicated in the frequency of requests. Other evidence provided by the DHHS Information Sharing Team indicated an increase in information requests of 19% during the coronavirus pandemic period, which suggests that there may be specific forms of information sharing activity that have increased, while other types of requests have decreased.

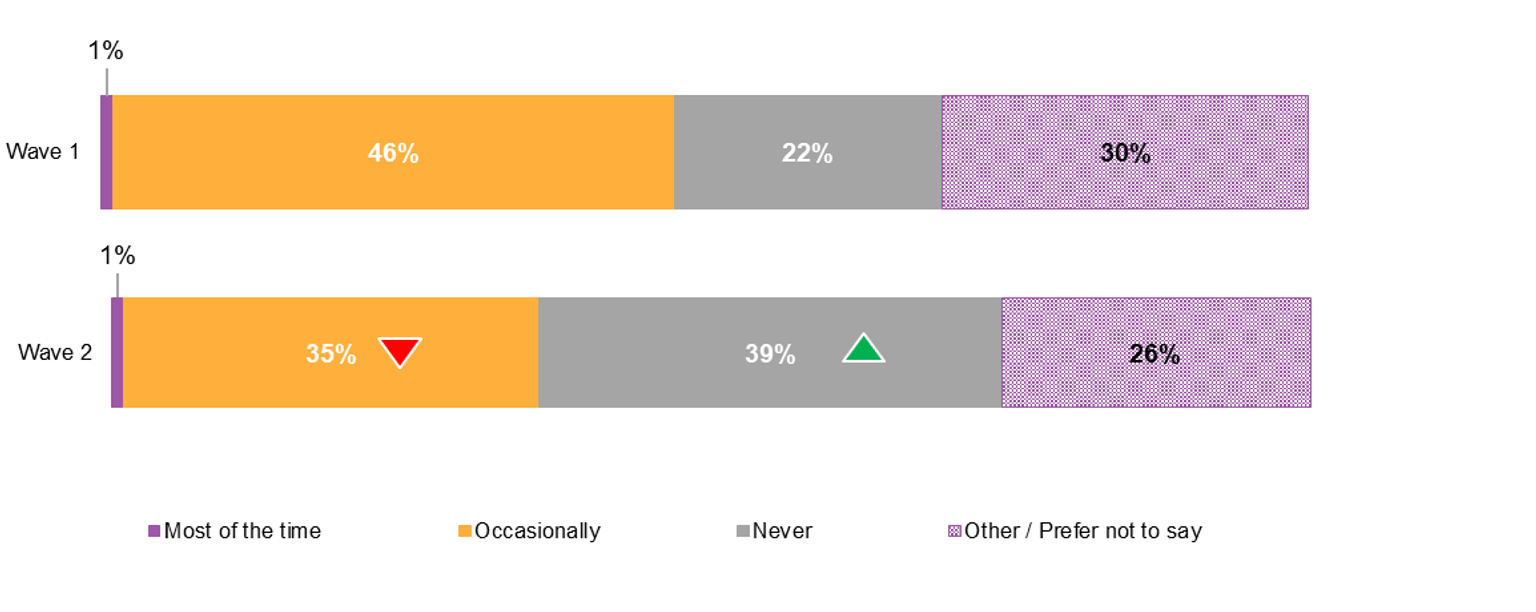

However, while there was little change in what was already a relatively high level of reported child information sharing activity, prescribed workforces surveyed indicated in 2020 that they were less likely to refuse an incoming request for information after the implementation of the CIS Scheme suggesting that access to information has improved. Figure 5.1 shows how often prescribed workforces refused a request for information at baseline and follow-up surveys.

The proportion of prescribed workforces who indicated that they occasionally refused incoming requests for information decreased significantly by 11 percentage points, from 46% to 35%, and the proportion that indicated they never refuse incoming requests for information increased substantially by 17 percentage points, from 22% to 39%.

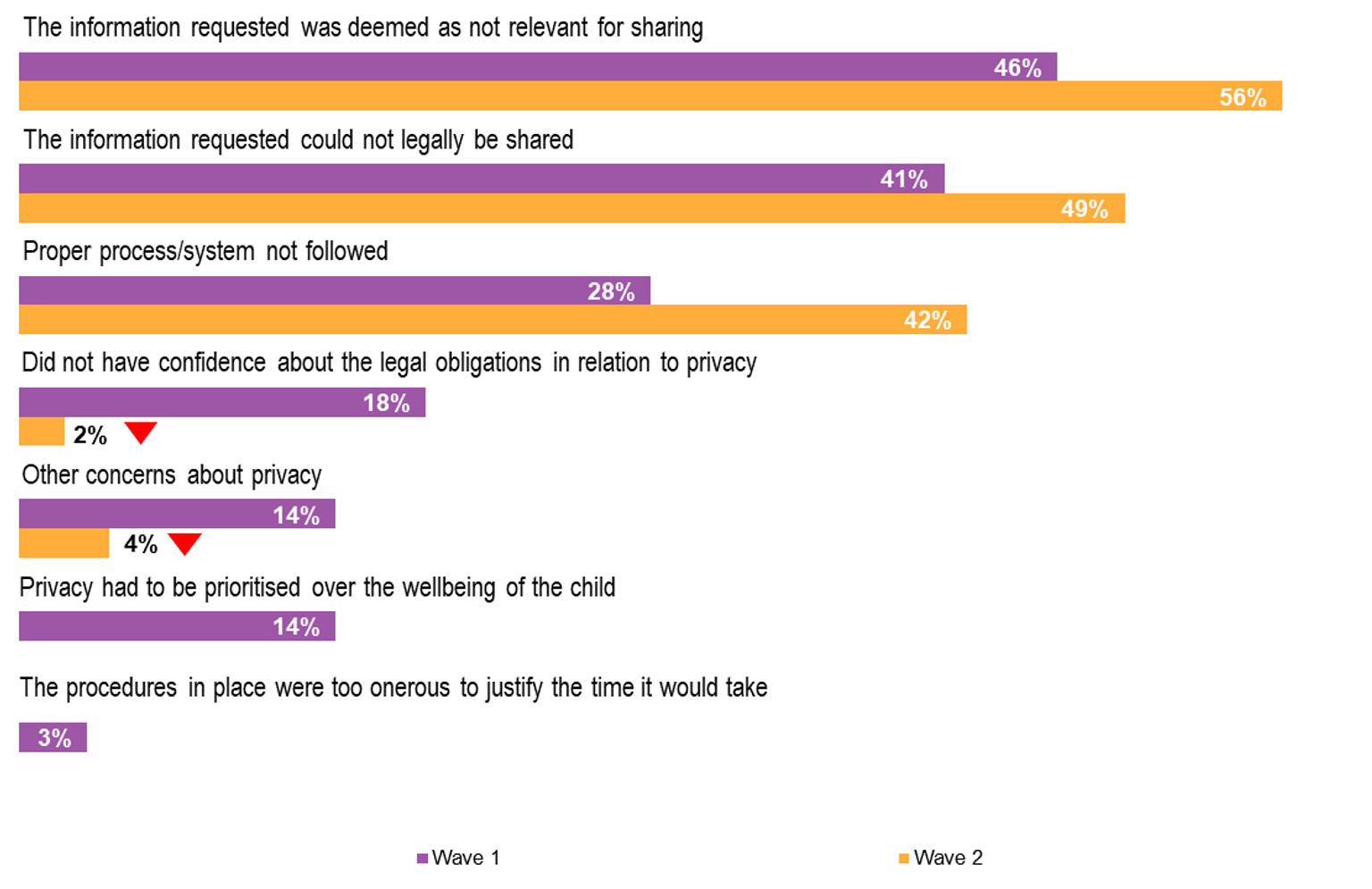

Figure 5.2 shows the commonly cited reasons for refusals of incoming requests for information.

Reasons relating to the relevance and legality of information that had been requested had both increased slightly, suggesting that there is greater clarity in the assessment of incoming requests for information. This is supported by the change in reasons for refusal related to privacy which have all fallen sharply. Workforces who refused requests for information because they did not have confidence about their legal obligations in relation to privacy fell from 18% to 2%, while the proportion who had other concerns about privacy fell from 14% to 4%. There were no reports of respondents refusing a request for information because they had prioritised privacy over the wellbeing of a child

However, there was a substantial increase in incoming requests for information being refused for not following proper processes or systems, from 28% to 42%. While lack of conformity to ‘processes and systems’ will impact timeliness of access to information, it might be expected that this issue could be addressed, resulting in the successful sharing of information between ISEs, and that over time, familiarity with proper/preferred processes of other entities will streamline access to information.

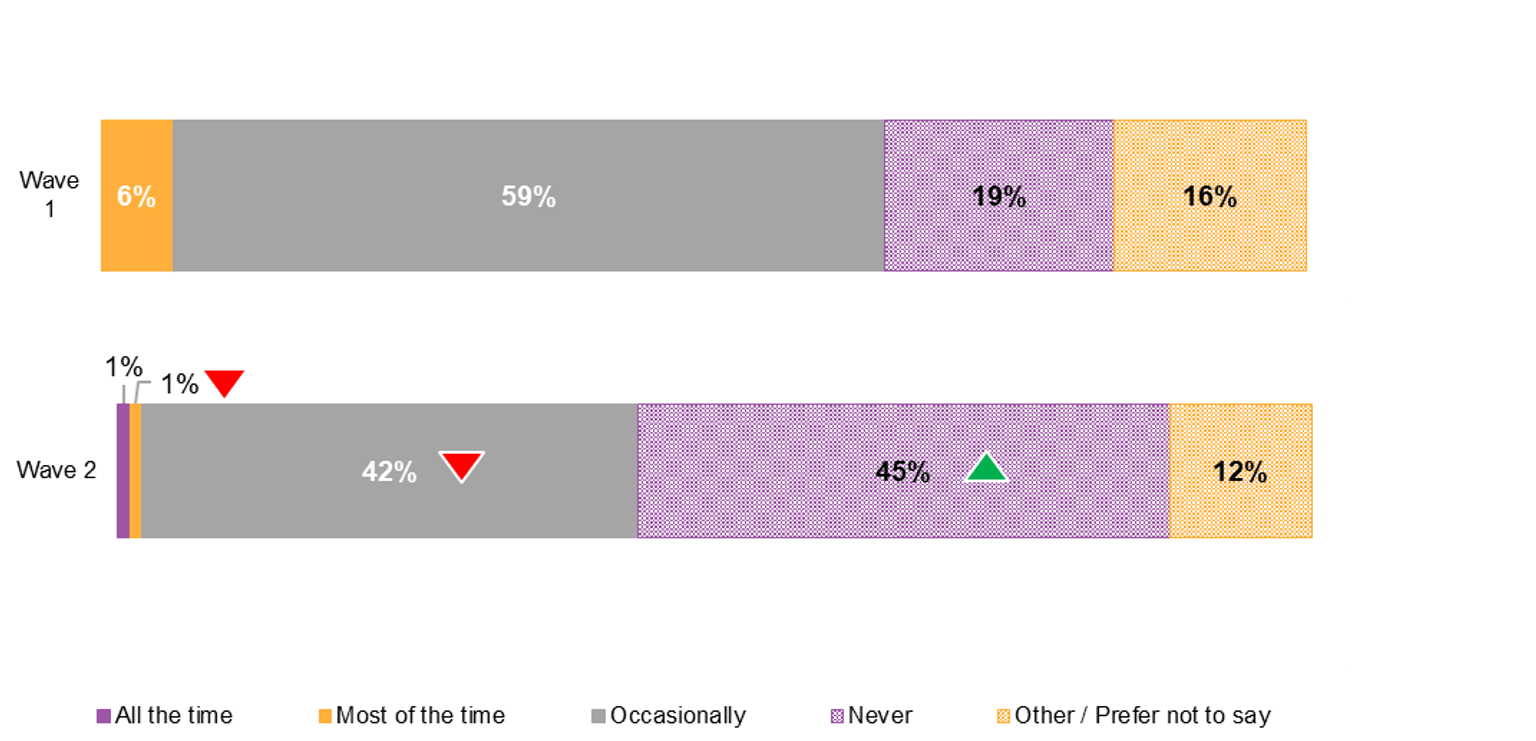

In relation to outgoing requests for information, the frequency with which outgoing requests for information were refused is provided in Figure 5.3.

The frequency of refusals of outgoing requests for information among prescribed workforces has also declined. There was a significant increase of 26 percentage points in workforces reporting that their requests for child information were never refused in the 12 month period following commencement of the CIS Scheme, changing from 19% prior to introduction of the Scheme to 45%. A corresponding decrease in occasional refusals of outgoing requests was reported reducing by 17 percentage points from 59% to 42%.

Although there was little experience of outgoing requests for child information being refused most of the time prior to the CIS Scheme, this had also improved falling from 6% to 1% following introduction of the CIS Scheme.

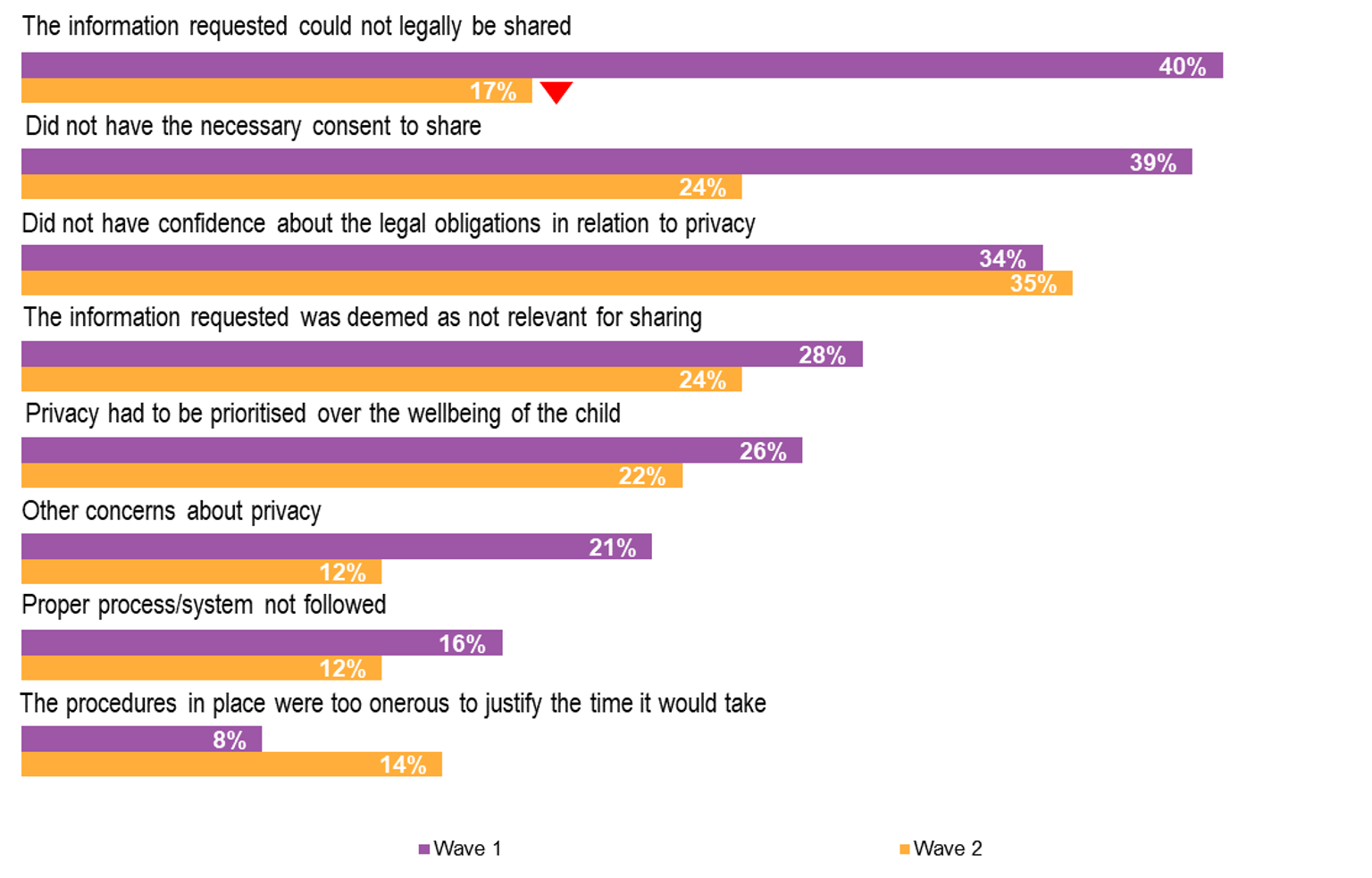

The distribution of the most commonly cited reasons for why an outgoing request for information was refused is provided in Figure 5.4.

Prior to introduction of the CIS Scheme, the most commonly cited reasons for why outgoing requests for child information had been refused related to the legality of sharing the requested information and having the necessary consent to share. In the follow-up survey of workforces, there was a substantial reduction in the proportion of respondents attributing refusals to these reasons, strongly endorsing the purpose of the legislated CIS Scheme.

However, about one third of respondents continued to report that they had been refused a request for information because of a lack of confidence about the legal obligations in relation to privacy, and around one quarter that privacy had been prioritised over the wellbeing of the child. The continuing concerns about privacy as a reason for being refused a request for information to be shared appears to support stakeholder feedback about the ongoing need to educate other organisations/workforces about the provisions of the CIS Scheme. For the cohort of respondents to the workforces surveys, privacy concerns no longer feature as a common reason for them to refuse an incoming request for information (see Figure 5.2) suggesting that in this respect the cohort may have a better understanding of the operation of the CIS Scheme, and potentially an improved appreciation of the circumstances for sharing information more generally.

Approximately one quarter of workforces surveyed continued to report that outgoing information was refused because it was deemed not relevant to share. The issue of relevance is especially highlighted as the most common reason for refusal of incoming requests. It could be expected that a deeper understanding of how information held by other organisations will contribute to a better understanding of a child’s circumstances will improve the perception of relevance and practice of effective information sharing.

5.1.2 Effectiveness of child information sharing

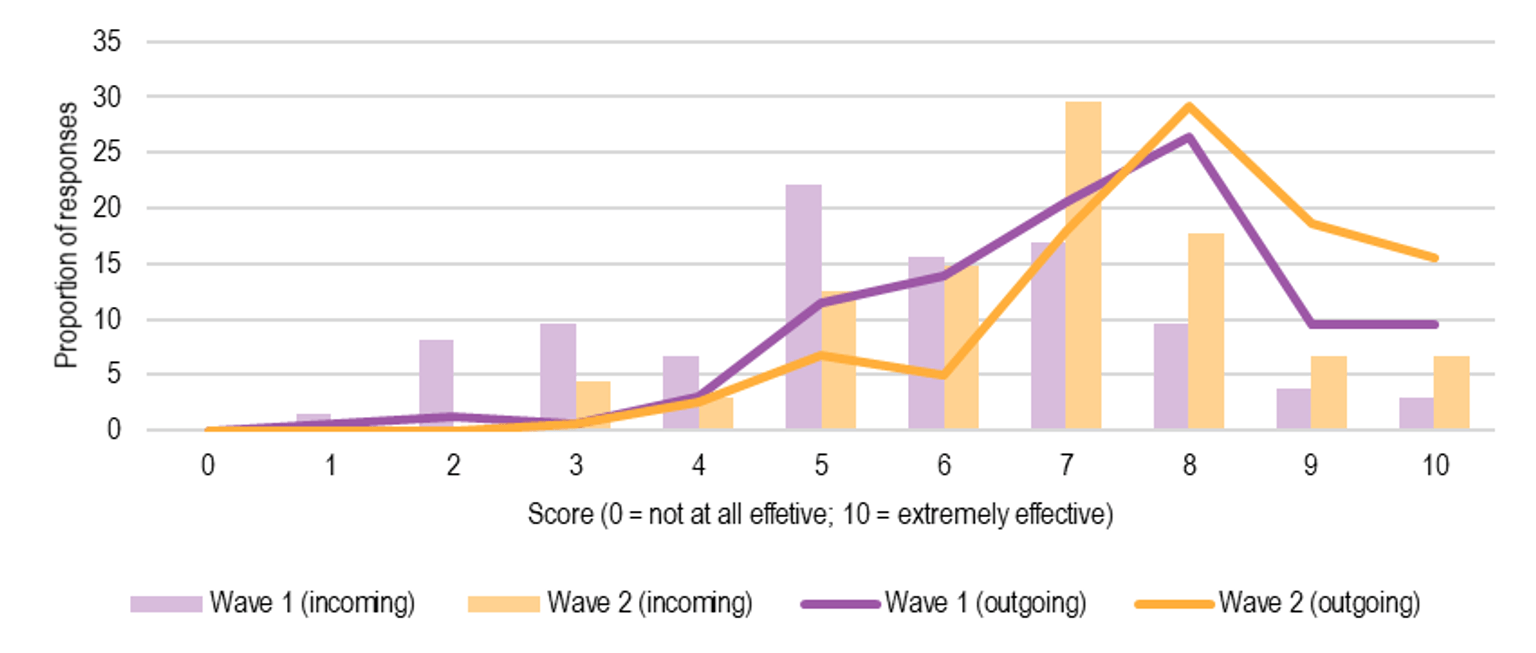

On the matter of how effective organisations are in sharing child information, prescribed workforces perceived that practices in both sharing and requesting information had improved (see Figure 5.5), further supporting earlier evidence of improved access to information.

While prescribed workforces surveyed indicated that the level of information sharing activity had not changed since introduction of the CIS Scheme, respondents did feel that the capacity of their organisation and that of other organisations to share child information had improved following operation of the CIS Scheme. The average score given to perception of the effectiveness of their organisation in providing information (outgoing) increased from 7.2 prior to the CIS Scheme to 7.9. Similarly, while the capacity of other organisations to share information (incoming) was not ranked as highly, their effectiveness in sharing was felt to have significantly improved from a score of 5.5 to 6.8 following operation of the CIS Scheme.

5.1.3 Promotion of child wellbeing

Enabling policy and legislative environment

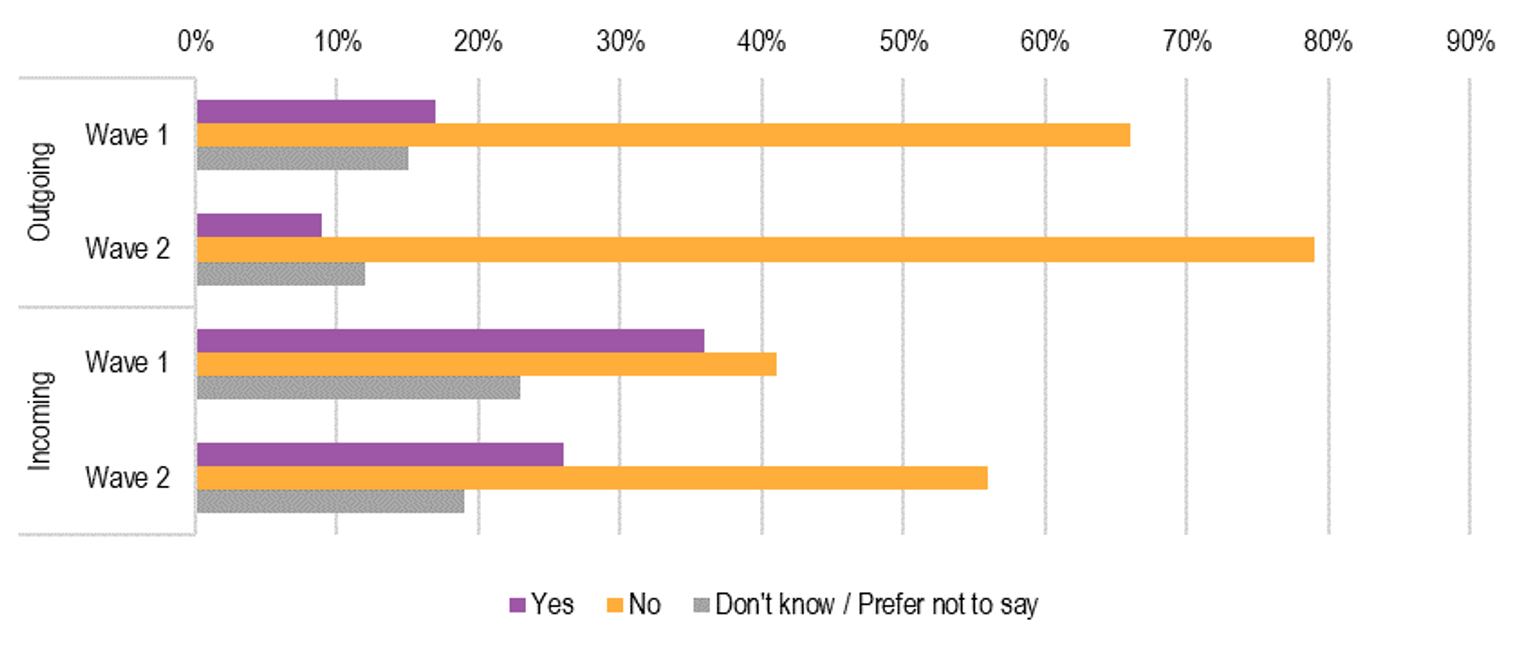

Based on the survey of prescribed workforces, in the period following commencement of the CIS Scheme, there were fewer encounters of a situation where a worker felt there was a need to provide information to promote the wellbeing of a child but was unable to act because of legal restrictions or organisational policies (see Figure 5.6).

Reports of encounters where promotion of child wellbeing was impeded reduced significantly by eight percentage points from 17% to 9% where information had been requested (outgoing) by other organisations. Consistent with this improvement, reports of never encountering legal or policy impediments in relation to outgoing information improved by 13 percentage points from 66% to 79%.

Similar restrictions experienced on the ability of prescribed workforces to act on promotion of child wellbeing were reported when requesting information (incoming). A greater proportion of workforce respondents indicated that they had encountered legal or policy restrictions in seeking child information from other organisations and this remained relatively high following introduction of the CIS Scheme (Figure 5.6 also refers). About one third of respondents indicated that they had encountered this situation where acting on promoting child wellbeing had been impeded in the period before the CIS Scheme came into effect and this reduced to approximately one quarter of respondents following introduction of the CIS Scheme. There was a significant increase to just over half of respondents who had not encountered these restrictions on requests for information to enable them to act to promote child wellbeing, increasing by 15 percentage points from 41% prior to the CIS Scheme to 56% at follow up.

Threshold for information sharing

Evidence from multiple sources of data collected suggests that there has been a positive impact of the CIS Scheme in early identification and intervention of child wellbeing issues. The survey of workforces shows an increased ability to act on promotion of child wellbeing and workforces appear to be more effective at sharing information. There is also an indication that information sharing is now being used for cases where the risks are not as severe, compared to prior to implementation of CIS Scheme. This suggests a cultural shift towards earlier identification and intervention.

There appears to be a lowering of thresholds before staff think about seeking information – staff are beginning to request information even when circumstances are not severe or dire, or when they are not really serious or extreme. (Workshop participant)

Comprehensive assessment

In addition, there was feedback that the CIS Scheme has helped prescribed workforces have a better understanding of the different types of information that are held by different ISEs, and therefore a greater appreciation of how that information might assist in developing a more comprehensive and thorough assessment of risks and needs.

Within our staff their practice has been to expand their data sources when doing assessment and planning. The increased quality of assessment and planning is down to having more information from different sources to paint a more complete picture. (Workshop participant)

Prescribed workforces surveyed about the agencies with whom they most often share child information reported that while Child Protection remains the most commonly cited agency that information was shared with and requested from, there has also been increased engagement with Family Services and Specialist family violence services since operation of the CIS Scheme.

Role clarity

However, there were a number of other stakeholders who felt that the nature of their work and/or their organisations meant that it was difficult to consider early identification and intervention to improve the wellbeing of children. Such prescribed organisations and services were typically those operating at the crisis end of the service spectrum, such as domestic and family violence crisis services. Workers from these services are typically presented with issues of immediate risk and safety, and their role in early intervention and prevention is less clear.

Often by the time they get here (family violence service) it is not early intervention, and child-related issues are reported under mandatory reporting. Early identification and intervention are part of the CIS Scheme but it seems quite difficult to apply to the family violence sector. (Peak/lead body)

Risk and safety tends to be more of a concern for frontline services, and wellbeing is an afterthought for many of these workers. (Workshop participant)

A number of stakeholders also held the belief that early identification and intervention would be more applicable for universal services, as the nature of their interactions with children meant that they would be involved with children at a stage where promoting wellbeing was a focus. They therefore held the view that early identification and intervention would likely achieve its full effect after Phase Two of the CIS Scheme was implemented.

Universal services are more likely to operate from a wellbeing framework…schools, for example, are far more involved in the early intervention, prevention and support of children, so the true benefits will be seen in Phase Two. Organisations that don’t operate in the family violence space at all will be more likely to use the CIS Scheme. (Peak/lead body)

Overall, it appears that Phase One ISEs that have a component of child-focused practice have been able to use the CIS Scheme to improve their approach to early identification and planning through obtaining information from a wider variety of sources. However, it should be noted that tertiary services, with a greater focus on crisis response, have an important role in promoting child wellbeing. This can be seen, for example, in the application of the MARAM framework ensuring that the child is not overlooked in a family violence context, and through Child Protection referrals to Child FIRST alerting family support services to potentially vulnerable children. This illustrates the potential for tertiary services to be engaged in early intervention, and the importance of enabling the concept of a shared responsibility across the continuum of care.

It will be important to continue to enable Phase One secondary and tertiary services to actively seek opportunities to participate in child information sharing for purposes of promoting child wellbeing and safety. The implementation of Phase Two of the CIS Scheme should include strategies to strengthen existing and new efforts to leverage from the engagement with families and children of secondary and tertiary services, to optimise the extended support that might be available for shared clients.

| Recommendation 8: Role clarity in collaborative practice |

|---|

| That the implementation of Phase Two of the CIS Scheme includes strategies to strengthen collaboration between universal, secondary and tertiary services (that is, Phase One and Phase Two information sharing entities) around a child, to optimise benefits for the child, and to reinforce the contribution of Phase One prescribed workforces. |

5.2 Increased shared responsibility for child safety and wellbeing

Awareness of responsibility

In terms of shared responsibility for child safety and wellbeing, there appear to be some signs of positive impact. Overall, there has been a cultural shift among many information sharing entities, demonstrating that there is at least an improvement in the awareness of shared responsibility for child safety and wellbeing. This has led to an increased willingness to work together with other organisations and services to improve child safety and wellbeing.

There is an increased willingness for different parts of the organisation to work together…including people in different sectors understanding why child safety is important. (Workshop participant)

Where there was a pre-existing awareness of shared responsibility for child safety and wellbeing, the implementation of the CIS Scheme has reinforced this awareness and provided the opportunity for prescribed workforces to operationalise this shared responsibility.

Child safety is everyone’s business – this is becoming embedded more thoroughly than before. (Workshop participant)

Capacity to share

However, being able to act on this shared responsibility still required work to enable effective sharing of information.

Wellbeing is not considered sufficiently or uniformly…organisations that work with children or youth may not have a good understanding of how to record information robustly so that it can be shared with other organisations. (Peak/lead body)

The CIS Scheme has significantly influenced the attitudes of workforces and increased the awareness and understanding of shared responsibility for child wellbeing and safety, but increased efforts are needed to ensure that prescribed organisations and services have the capability and capacity to put this into practice.

Organisations have shifted in culture, but we need to drive the practice uplift more – people want to share but don’t know how to share, or how to share properly and well. (Workshop participant)

Proactive information sharing

The practice of proactive sharing or volunteering of information is also supported by the CIS Scheme and forms an important part of enabling earlier intervention. Some stakeholders believed that, as the CIS Scheme matures and workforces become increasingly familiar with the work that other organisations do, proactive information sharing will become an increasingly common practice.

Also, as their (workforces) skills mature in CIS Scheme they will probably increase in proactive sharing. (Key informant)

One example of how this has been effectively applied is illustrated in Box 5.2. For the Commission for Children and Young People, the CIS Scheme has met a gap in their powers to volunteer child information when considered appropriate. Being able to proactively share has provided staff with an additional avenue for supporting the wellbeing and safety of the child, as well as educating other organisations about the value of the CIS Scheme. (Also see section 3.3 and section 4.3.)

Box 5.2 Case study – proactive information sharing

Situation and context

The Commission for Children and Young People (CCYP) is an independent statutory body responsible for promoting improvement in policies and practices affecting the safety and wellbeing of children and young people, with a particular focus on vulnerable children and young people.

CCYP have existing powers to request information through the Commission for Children and Young People Act 2012 and the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005.

Actions

CCYP’s existing legislative powers to request information are sufficiently broad and meet their needs, particularly in the investigation of child deaths and in operating the reportable conduct scheme. However, these powers are generally one-way and there is no capacity for CCYP to proactively share information with other organisations. There are also rare occasions where their powers cannot enable sufficient information sharing. These gaps have been addressed through the introduction of the CIS Scheme. CCYP have developed their own templates to assess the risks associated with disclosing information to others voluntarily and how to mitigate these risks.

Outcomes

CCYP now shares information with other ISEs voluntarily, while ensuring that these voluntary disclosures are appropriately assessed for their relevance and risks. In making these disclosures under the CIS Scheme, they have been able to educate other organisations and promote use of the CIS Scheme where relevant. Within CCYP, there has also been a cultural shift among staff where staff are thinking proactively of the CIS Scheme wherever their existing powers are not able to enable information sharing, and also thinking of opportunities to share information voluntarily.

Source: Based on information provided by Commission for Children and Young People. ACIL Allen Consulting 2020

5.3 Collaboration and coordination between services

There is strong evidence that there has been increased collaboration and coordination between information sharing entities as a result of the CIS Scheme. This has occurred at a number of levels.

Among the different peak bodies, their involvement in a joint working group has allowed them to forge new relationships and consider how they might work together to jointly and efficiently develop new resources to share with their respective workforces. For example, Domestic Violence Victoria indicated that they were working with the Council of Homeless Persons in developing animated case studies through funding provided by Sector Grants, which is likely to result in the development of inter-sectoral expertise within the family violence specialist and homelessness services. There were also plans over the next twelve months to work with No To Violence and the Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare to develop collaborative risk management and a child-centred case management approach.

At an organisational level, there were examples of greater local collaboration as a result of implementing the CIS Scheme. For example, some organisations had implemented co-location to facilitate greater ease in information sharing but also to consider how best to implement information sharing between organisations and services that traditionally might not have worked together.

We had started to look at more co-location between organisations (e.g. one day a week) due to the increased information sharing activity prior to COVID-19, but this has since been put on hold. The co-location had been useful to understand other organisations and how different organisations can work better together. (Workshop participant)

Another avenue for coordination and collaboration has been through face to face training opportunities provided since the commencement of the CIS Scheme, which brought together participants from different organisations and sectors that were included in the prescription of Phase One information sharing entities. The structure of the training provided the opportunity for participants to interact with each other, allowing them to build relationships with people from different sectors. The activities as part of the training also allowed them to have greater insight into how different organisations and sectors might approach the same case differently.

The workshops allow them to break up into different groups to see the same case from the lens of different service providers and sectors…it really brings it home for the participants. (Peak/lead body)

While the coronavirus pandemic restrictions have meant that some of these activities (e.g. co-location and working together) have been interrupted, the gains in collaboration and coordination between services has continued through other activities. The training and workshops that are delivered virtually allow for significant levels of interaction between workforces from different sectors.

My experience is that COVID-19 pandemic restrictions have certainly disrupted direct client services, but it is also my experience that service collaboration and information sharing has increased. (Workforces survey respondent)

There was also feedback from peak/lead bodies that the increased capability generally and especially in regional organisations to communicate using virtual platforms had increased the capacity to deliver state-wide training/professional development more efficiently and with a greater level of participation from regional areas.

5.4 Supporting children’s access to and participation in services

The Review’s workforces survey findings indicated that the CIS Scheme has had a small impact on children’s access to and participation in services. At the baseline survey, 46% of participants responded positively to ‘increased safety/provision of services’ as a benefit of the CIS Scheme. At the follow-up survey of workforces, this had increased slightly to 55%.

While there was no other evidence of children’s increased access to and participation in services, a number of stakeholders indicated that there had been benefits in identifying children’s needs through an increased child focus as a result of the CIS Scheme. It could be expected that with consolidation of this increased awareness and understanding of children’s needs, increased opportunity will follow for more timely access to and participation in services.

A potential limiting factor raised by stakeholders is that many of the services that are involved in supporting children at an earlier stage are not yet prescribed. Examples were provided by MCH nurses, whose services are prescribed as part of Phase One of the CIS Scheme, wishing to work more collaboratively with other early childhood services. However, these early childhood services are not yet prescribed although planned for Phase Two.

As a result, it is likely that children’s access to and participation in universal services in particular, has not yet improved significantly but is likely to in the future. One example of how this could occur is illustrated in the following case study, which outlines how the CIS Scheme has enabled following-up of unregistered births, ensuring visibility and ability to provide a history of the child’s engagement with universal and other support services.

Box 5.3 Case study – filling crucial information gaps

Situation and context

The Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages (BDM) is a business unit within the Victorian Department of Justice and Community Safety responsible for the registration and record keeping of significant life events for the Victorian community. These records allow accurate record keeping and serve important functions, such as proof of identity, tracing family history and providing important statistical data for research and government planning.

In particular, the registration of births is significant for children as it establishes a child’s legal identity, supports their ability to access vital services, and improves their visibility in the community. However, there are typically a number of unregistered births each year for various reasons.

Actions

BDM undertook a pilot process strategically aimed at using the CIS Scheme to support the performance of Registrar-prescribed functions that promote child wellbeing. The objective was for BDM to proactively request information from Maternal and Child Health (MCH) services to facilitate birth registration of a sample group of 16 children born in 2017 with unregistered births, where BDM had no other ability to contact the children’s mothers.

Outcomes

All 16 information requests across 12 local government areas were successfully shared and responded to, with new contact information for 14 mothers received. BDM was able to successfully contact five mothers, resulting in two birth registrations and a third pending registration requiring the father’s participation. The pilot provided valuable insight and actionable recommendations to enhance practices and communication tools in the future (such as development of a Birth Registration Online guide to assist MCH to support parents in registering births), as well as enhanced the relationship between BDM, MAV and local councils.

Source: Based on information provided by Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages. ACIL Allen Consulting 2020

It could be expected that improved registration of births will also benefit the accuracy and value of the Child Link initiative currently under development.

Updated