Confidence

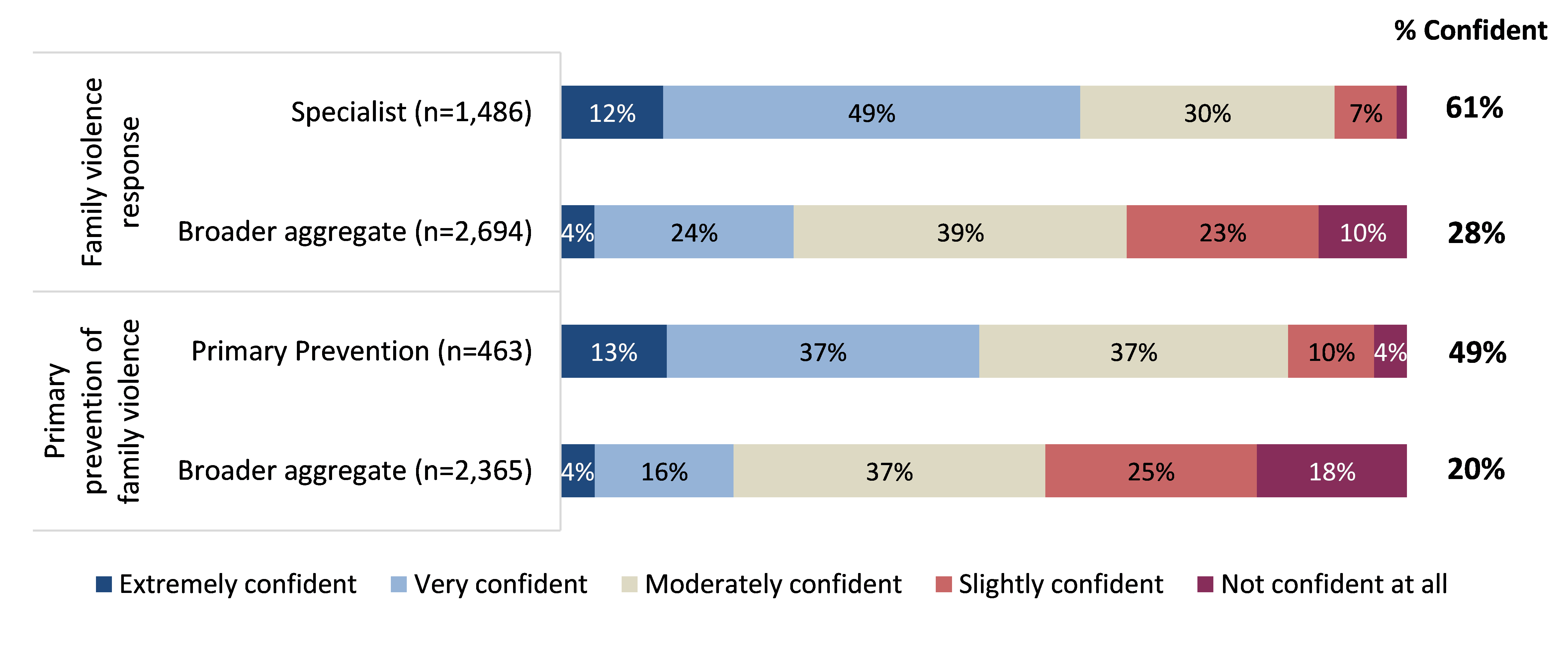

Around three-in-five specialists indicated that they were ‘extremely’ or ‘very’ confident that they have had enough training and experience to effectively perform their role(s) in relation to family violence response (61%). Those in the broader workforce were also asked about their level of confidence, with only 28% indicating that they were confident.

In relation to the primary prevention of family violence, around half of primary prevention practitioners indicated they were at least very confident (49%), whilst just one-in-five respondents from the broader workforce indicated they were at least very confident (20%).

When asked about what additional support would increase their confidence in performing their role, all workforces indicated that information sharing and collaboration was most important.

MARAM

- 92% of the specialist workforce had heard of the MARAM framework.

- 79% of the primary prevention workforce had heard of the MARAM framework

- 53% of the aggregate broader workforce had heard of the MARAM framework.

The three broader workforce sub-groups with the greatest awareness of the MARAM framework were maternal and child health (95% were aware); alcohol and drug services (86%); and housing and homelessness (80%); whilst ambulance services reported the lowest awareness (7%, see Table 7).

| Workforce | Aware of the MARAM framework (% Yes) | Organisation prescribed to align with the MARAM framework (% Yes) | I have a good understanding of my professional responsibilities under the MARAM framework (% Agree) | In identifying or assessing FV risk, I always use MARAM tools, including a structured professional judgement approach (% Agree) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specialist family violence response (n=946-1,482) |

92% | 81% | 79% | 62% |

| Primary prevention (n=131-474) |

79% | 52% | 56% | 34% |

| Broader workforce aggregate (n=838-2,711 |

53% | 67% | 63% | 39% |

| Alcohol and Drug services (n=119-202) |

86% | 76% | 63% | 35% |

| Ambulance services (n=5-149) |

7% | 55% | Supressed (low sample size) | Supressed (low sample size) |

| Broader community services (n=613-1,401) |

68% | 73% | 61% | 36% |

| Children, Families and Child Protection (n=213-388) |

80% | 78% | 68% | 44% |

| Community Health Services (n=119-306) |

62% | 72% | 53% | 34% |

| Community Mental Health Services (n=71-192) |

61% | 68% | 50% | 24% |

| Court Services (n=19-105) |

50% | 49% | 54% | 37% |

| Disability Services (n=10-119) |

24% | 38% | 73% | 40% |

| Education (n=12-259) |

25% | 23% | 57% | 17% |

| Housing and Homelessness (n=89-167) |

80% | 72% | 54% | 30% |

| Justice (n=33-112) |

61% | 66% | 67% | 45% |

| Legal Services (n=4-58) |

57% | 24% | Supressed (low sample size) | Supressed (low sample size) |

| Maternal and Child Health (n=90-126) |

95% | 90% | 70% | 46% |

| Other Community Services (n=79-269) |

59% | 61% | 60% | 29% |

| Police (n=39-129) |

57% | 60% | 81% | 72% |

| Public health (n=68-523) |

27% | 58% | 53% | 31% |

| Settlement Services (n=8-31) |

48% | 67% | Supressed (low sample size) | Supressed (low sample size) |

| Youth Work (n=57-111) |

78% | 72% | 65% | 32% |

Training

All three workforces were asked to identify the family violence prevention and response topics that they had completed training in, and those they would like further training in. Table 8 illustrates the key findings, by workforce. The top three barriers to accessing further training / development are also shown below.

| Training completed | Helpfulness of completed training (% Helpful) | Training desired in future | Main barriers in accessing further training and development |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Specialist FV response(n=1,415) |

(n=921-1,013) |

(n=1,155) |

(n=1,457) |

|

Family violence risk assessment and risk management (CRAF) (73%) |

75% |

Working with people with disabilities (50%) |

Lack of time (52%) |

|

Identifying and screening family violence (69%) |

82% |

Sexual assault in family violence (48%) |

Cost of study (42%) |

|

Trauma-informed practice (67%) |

88% |

Working with adolescents (48%) |

Location of training facility (32%) |

|

Primary prevention(n=433) |

(n=209-248) |

(n=376) |

(n=461) |

|

Gender equity (59%) |

80% |

Working with Aboriginal communities(52%) |

Lack of time (57%) |

|

Foundation / introductory primary prevention of violence against women (58%) |

75% |

Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) (50%) |

Cost of study (42%) |

|

Recognising and responding to disclosures (50%) |

76% |

Managing backlash and resistance(49%) |

Location of training facility (32%) |

|

Broader workforce aggregate*(n=2,477) |

(n=955-1,024) |

(n=1,941) |

(n=2,603) |

|

Identifying and screening family violence (43%) |

67% |

Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) (59%) |

Lack of time (44%) |

|

Trauma-informed practice (42%) |

83%

|

Legal issues for family violence (49%)

|

Cost of study (35%)

|

| Family violence risk assessment and risk management (CRAF) (39%) | 62% | Working with perpetrators of family violence (48%) | Location of training facility (27%) |

Updated