- Published by:

- Family Safety Victoria

- Date:

- 25 Nov 2021

Read our strategic plan

Acknowledgement of Country

Family Safety Victoria proudly acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the lands across Victoria and pays its respects to all First Peoples. We acknowledge that sovereignty over this land was never ceded. This is Aboriginal land; always was, always will be. We recognise and value the ongoing contribution of Aboriginal people and communities to Victorian life, and particularly acknowledge the long-standing leadership of Aboriginal communities and Elders in Victoria in preventing and responding to family violence and improving outcomes for Aboriginal people, children and families.

Acknowledgement of victim survivors

Family Safety Victoria acknowledges adults, children and young people who have experienced family violence, sexual violence, and all forms of violence against women and children. We recognise the vital importance of family violence system and service reforms being informed by their experiences, expertise and advocacy. We also remember and pay respects to those who did not survive and acknowledge all those who have lost loved ones to family violence. We keep forefront in our minds all victim survivors of family violence and sexual violence, for whom we undertake this work.

Statement of support for Aboriginal self-determination

Family Safety Victoria is committed to the principles and approach underpinning the Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum’s Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong culture, strong peoples, strong families.

This Aboriginal led 10-year Agreement and its Action Plans commits communities, services and Government to work together and be accountable for ensuring that Aboriginal people, families and communities are stronger, safer, thriving and violence-free, built on the foundation of Aboriginal self-determination.

Self-determination requires Government to:

- value and respect Aboriginal knowledge, systems and expertise

- transfer authority, decision making control and resources to Aboriginal people.

This requires a significant cultural shift and a new way of working together. The Government acknowledges that this will ensure better outcomes for Aboriginal people and stronger, safer families and communities.

Aboriginal self-determination in a family violence context

requires the transfer of power, control, decision making and resources to Aboriginal communities and their organisations by:

- investing in Aboriginal self-determining structures to lead governance, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of family violence reform

- transferring decision making for policy development and program design by prioritising funding to Aboriginal communities and their organisations

- investing in community sustainability, resourcing and capacity building to meet the requirements of the new reforms

- growing and supporting the skills and knowledge base of the Aboriginal workforce and sector to support self-determination

- ensuring that government and the service system is culturally safe, transparent and accountable

- and ensuring that community have access to culturally informed, safe service provision and programs by the non-Aboriginal service sector.

Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way Agreement

Family Safety Victoria is committed to Aboriginal-led collective action, Aboriginal self-determination, and systemic change which addresses bias and institutional racism, whilst centring Aboriginal voice and decision-making in the prevention of family violence in Aboriginal communities.

In the Family Safety Victoria Strategic Plan 2021-2024, ‘Aboriginal’ refers to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. ‘Indigenous’ or ‘Koori/Koorie’ is retained when part of the title of a report, program or quotation.

CEO's message

Introducing our strategy.

At Family Safety Victoria we are motivated and inspired by delivering an ambitious reform program to ensure family violence and the inequalities which underpin it are no longer tolerated in Victoria.

Since 2017, we have driven much of Victoria’s nation-leading efforts to create transformative change across systems and services, and our three-year Strategy comes at a critical time for the strategic reforms underway in Victoria.

Between 2021-2024 we will continue to deliver the state-wide 10-year plan to end family violence, to ensure services are more connected, sustainable and deliver better outcomes for survivors, for children and for families.

We embed an Aboriginal-led approach to family violence reforms in Aboriginal communities, informed by the long-term agreement with government Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families. Our approach centres Aboriginal communities’ self-determination and strengths and places the expertise of specialist services and people with lived experience at its heart.

Our work over the next three years builds on achievements delivered in collaboration with our partners, which are all the more remarkable given the challenges brought on by the coronavirus pandemic.

In 2020, specialist services reported increases in the frequency and severity of violence against women and an increase in the complexity of women’s and children’s needs. This trend of rising reports of family violence, which started prior to the pandemic, is expected to continue as reporting rates more accurately reflect the levels of family violence in our community.

We recognise that increasing demand for services requires workforce growth, development and resourcing. Improving data and evidence, stimulating innovation and improvement, and facilitating and supporting sustainability for specialist services and our systems will be an essential part of our work.

We will continue to build a family violence, sexual violence and primary prevention workforce that is valued, skilled, empowered and supported, in accordance with Building from Strength: 10-year Industry Plan for Family Violence Prevention and Response.

We will also continue to lead the cross-government coordination and delivery of the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) Framework which, together with the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme and Child Information Sharing Scheme, is being expanded to many more workforces from 2021.

We prioritise working in partnership with peak bodies, services, and other stakeholders. We also resource and support delivery of state-wide and local specialist family violence services, sexual violence services, perpetrator services, Aboriginal services, and services that support children and young peoples’ safety and wellbeing.

The establishment of The Orange Door network remains a priority, which provides help and support for family violence, and for families in need of support with the wellbeing of children. As at October 2021, The Orange Door Network now operate in more than ten of 17 government areas and forms an integral part of the family violence and family services systems in Victoria.

In order to maximise access to safety and specialist support, we also continue to lead the refuge reform program, and aim to ensure crisis accommodation and support pathways offer expanded and more stable housing options to help more families. Building on the cross-government plan to hold perpetrators to account, we will continue to work with the specialist and wider sector to ensure interventions with people who use violence are effective and accessible. This includes expanding community-based perpetrator interventions beyond men’s behaviour change programs to case management and targeted services for people in different communities.

We continue to prioritise delivery of the highly acclaimed Central Information Point, a multiagency system which provides comprehensive information about perpetrators’ family violence history and patterns of behaviour, to support risk assessment for better informed and targeted safety planning.

Our stewardship role in delivering whole of government reform is a vital part of our role. We work collaboratively with other government departments to ensure legislation, strategy and policy is informed by expertise held by people with lived experience and by specialist services. This includes, for example, delivering a research agenda which will provide deeper insights and opportunities for innovation that have emerged from the pandemic, and supporting the development of a whole of government Sexual Violence and Harm Strategy.

From November 2021, we are excited to be working within the newly established Department of Families Fairness and Housing, which will enable even closer collaboration with Housing and Homelessness, Child and Family Services and Child Protection work programs. We will also continue to work closely with other departments, Victoria Police, courts and legal services to maximise access to effective support and to hold perpetrators to account.

What unites us across Family Safety Victoria is our values and knowing that how services are delivered is as important as what is delivered. We are committed to person-centred, strengths-based approaches, to Aboriginal self-determination and to giving greater visibility to children’s rights.

We also aim to ensure survivors most disadvantaged and discriminated against by systems and services are at the centre of system and service reform, and that the action we take helps dismantle the intersecting structural inequities that limit the lives of people we work with in our

communities.

We’re at the halfway point of the state’s 10-year plan to rebuild Victoria’s family violence system and there’s still a long way to go. We know that family violence is not inevitable. It is entirely preventable with the necessary public and political will and resources allocated to achieve this goal. We now have a great chance of achieving this in Victoria.

This Strategic Plan demonstrates Family Safety Victoria’s collective commitment towards building a service system that is connected, inclusive and works together to help keep adults, children and families safe and supported. It also sets out our contribution towards survivors living in freedom from violence and oppressions, and towards our shared goal of preventing family violence, sexual violence, and all forms of violence against women and children, for good.

Eleri Butler, CEO Family Safety Victoria

The problem

Family violence and sexual violence is widespread and causes physical, sexual, psychological, economic, social and cultural harm, particularly to women and children. Family violence and sexual violence destroys families and communities and undermine our ability to achieve equality in our communities.

Family violence occurs when a perpetrator exercises power and control over another person. It involves coercive and abusive behaviours that are designed to intimidate, humiliate, undermine and isolate - resulting in fear and deprivation of liberty. These behaviours can include physical and sexual abuse, as well as psychological, emotional, cultural, spiritual and economic abuse.

Sexual violence includes rape and sexual assault, unwanted touching or sexual comments, sexual harassment, being forced to participate in pornography or the sex industry and technology-facilitated or image-based abuse. Sexual exploitation can also take place in a family context and is a form of sexual abuse, where offenders use power over a child or young person to sexually or emotionally abuse them.

While both men and women can be perpetrators and men, women and children can be victims, overwhelmingly the majority of victims are women and children, and the majority of perpetrators are men.

Family violence is not part of Aboriginal culture, but family violence impacts on Aboriginal people at vastly disproportionate rates and can have a devastating effect on Victorian Aboriginal communities. Contributing factors include colonisation, dispossession of land and culture and the wrongful removal of children.

Family violence can take many forms. It can occur within intimate relationships, extended families, kinship networks, intergenerational relationships and through family-like or carer relationships. This may include trafficking, forced marriage, stalking and harassment, sexual exploitation, female genital mutilation (FGM), dowry or migration-related abuse.

Intimate partners, family members and non-family carers can perpetrate violence against people with a disability. Violence can be perpetrated by adult children of the victim. Young people can use violence or be victims of violence within their family. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, gender diverse, intersex and queer (LGBTIQ) people may experience violence in their relationships or family of origin.

Children’s experiences in families, such as child abuse, neglect, family violence, bullying, isolation, social disadvantage, family ill-health, poverty and discrimination, can have serious consequences, especially when they occur early in life, are chronic, severe, or cumulative. We know that adversity does not predestine children to poor outcomes. Most children are able to recover when they have the right support at the right time, particularly the consistent presence of a safe and supportive caregiver. These experiences affect children differently, depending on individual, family and environmental protective and risk factors.

At its core, family violence is reinforced by gender norms and stereotypes. It is rooted in the inequality between women and men, and its intersection with inequalities connected to colonialism, racism, class, sexuality, age, disability and religion. This environment fosters discriminatory attitudes and behaviours that condone violence and allow it to occur. For this reason, addressing gender inequality and discrimination is at the heart of preventing family violence, and other forms of violence against women.

- In Australia, one in 3 women has experienced physical violence since the age of 15, and one woman a week is killed by her intimate partner.1 Intimate partner violence is the greatest health risk factor (greater than smoking, alcohol and obesity) for women in their reproductive years.2

- In Australia, one in 5 women has experienced sexual violence since the age of 15. Almost 2 million Australian adults had experienced at least one sexual assault since the age of 15. The majority (97%) of offenders recorded by police are male.3

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are between 2 and 5 times more likely than other Australians to experience violence as victims or offenders. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are 35 times more likely to be hospitalised due to family violence-related assaults than other Australian women.4

- 1.4 million Australian adults (8%) have experienced sexual abuse before the age of 15. In 2018–19, sexual abuse was recorded as the primary type of abuse for about 10% of the 47,500 children who had substantiated cases of child abuse.5

- In 2018, police recorded around 7,900 sexual assaults against children aged 0–14 at the time of being reported to police. This equates to a rate of 167.6 sexual assaults recorded per 100,000 children, a higher rate than for people aged 15 and over.6

- Australian research and international data suggest that intimate partner violence occurs in LGBTIQ populations at similar levels as within the heterosexual population.7

- In the last 12 months in Australia, people with disability are at 2.6 times the risk of intimate partner violence in comparison to people without disability.8 90% of Australian women with an intellectual disability have been subjected to sexual abuse, 68% before they turn 18.9

- At the end of 2020, the police received 92 reports of forced marriage, which as we know, constitutes family violence and is a criminal offence. Over half of victims were under the age of 18, and victims most vulnerable to forced marriage were girls aged 15 to 19.10

- In Australia at least 11 girls every day are at risk of female genital mutilation (FGM), which as we know constitutes family violence, is a criminal offence, and causes lasting physical and psychological damage. The number of women and girls in Australia at risk of FGM has more than doubled since 2014 and over 200,000 survivors need support.11

References

- OurWatch, https://www.ourwatch.org.au/quick-facts/

- ANROWS, 2016, https://www.anrows.org.au/publication/a-preventable-burden-measuring-and-addressing-the-prevalence-and-health-impacts-of-intimate-partner-violence-in-australian-women-key-findings-and-future-directions/

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/domestic-violence/family-domestic-sexual-violence-in-australia-2018/summary

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2006, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous-australians/family-violence-indigenous-peoples/contents/executive-summary

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2020, https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/0375553f-0395-46cc-9574-d54c74fa601a/aihw-fdv-5.pdf.aspxinline=true#:~:text=Sexual%20assault%20against%20a%20child,of%2015%20(ABS%202017)

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2020, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/australias-children/contents/justice-and-safety/children-and-crime

- Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2015, https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/intimate-partner-violence-lgbtiq-communities

- Centre of Research Excellence in Disability and Health, 2021, ‘Nature and extent of violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation against people with disability in Australia’

- Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) 2010, http://www.alrc.gov.au/publications/family-violence-national-legal-response-alrc-report-114

- Australian Federal Police, Media release, 2020, https://www.afp.gov.au/news-media/media-releases/stop-human-trafficking-happening-plain-sight

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2019, https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/c11f1392-8343-4672-bee3-c296eaa019e4/aihw-phe-253.pdf.aspx?inline=true

Our vision, purpose, values and approach

Our vision

We want a future where all Victorians are safe, thriving, and live free from violence, and children grow up in environments built on gender equality and respectful relationships, in families that promote their health, development and wellbeing.

Our purpose

To achieve our vision, we focus on:

- facilitating person-centred and inclusive services so people receive the help they need, when they need it

- keeping perpetrators accountable, connected and responsible for stopping their violence

- working across government and with the family violence and sexual assault sectors and with family services to build a sustainable and coordinated service system

- partnering with those who have specialist expertise including lived experience to guide what we do

- building the evidence base about what works

- leading the family violence reform agenda to influence policy and strategy across government

Our values

We commit to delivering our work in accordance with the Victorian Public Service and Department of Families Fairness and Housing values and behaviours:

- responsiveness

- integrity

- impartiality

- accountability

- respect

- leadership.

We will work for the protection of human rights and challenge inequalities and discrimination to achieve social change for the benefit of all, because we know family violence is a violation of human rights and is entirely preventable.

The root causes of family violence and sexual violence are:

- gender inequality and discrimination, shaped by economic, political and social factors, systems and norms, policy and legal frameworks

- historical factors (e.g. cultural practices, colonisation)

- structural distinctions on the basis of sex, gender identity, ethnicity, sexuality, disability, age, class, income and other characteristics.

The following values have also been identified by our people as underpinning our approach to this work:

We are honest and transparent

We share information whenever we can and show consistency between our words and our actions.

We focus on our impact

We are purposeful, courageous and determined to achieve meaningful outcomes for our clients, stakeholders and the community. Our people are valued not just for the work that they do, but the way that they do it.

We are inclusive and work for social equity

We take responsibility for valuing and including everyone equally and for ensuring fairness and cultural safety wherever we do our work.

Our People and Culture Strategy sets out our goal of ensuring our people are valued, empowered, connected, inspired, and growing.

Health and wellbeing, and psychological and cultural safety, are as valued as productivity, and we strive to create an inclusive workplace culture, free from any type of discrimination. We encourage our people to have a strong voice, with opportunities to demonstrate leadership at any level, to have visibility and access to information and be involved or informed about decisions that directly affect them and their work.

We want our people to collaborate and feel connected, to each other and to our vision. We aspire to be a learning organisation, in which our people inspire each other and our partners, and are supported to develop the capabilities they need to excel.

Our approach

The principles of intersectionality, Aboriginal self-determination, lived experience and service system partnership are embedded throughout our work and inform our approach to all our strategic priorities.

Our strategic priorities

Our priorities will:

- build on our work to enshrine in law that certain agencies must identify, assess, and reduce family violence risk and respond to needs effectively

- build on the foundation of The Orange Door network, which provides a visible access point and response that meets needs, reduces risk, and promotes children’s wellbeing

- deliver the perpetrator accountability plan and focus effort on the source of the violence to ensure that our system works collaboratively to hold perpetrators accountable

- support the multi-agency Central Information Point, a system created to support specialist services gain a more accurate view of perpetrators’ risks and pattern of behaviour, from data held across multiple government systems. This information informs the risk and safety planning to support the safety of victim survivors. It also helps agencies disrupt and change patterns of behaviour of serial abusers who for too long have evaded accountability and challenge.

- ground our work in a thorough understanding of the diversity of people’s experiences, and the impacts of multiple forms of oppression on people’s lives

- focus on the experiences of people from diverse cultural, linguistic and faith backgrounds, people who are migrants, asylum seekers and refugees, people who are Deaf and who have a disability, people who identify as LGBTIQ, older people, children and young people, people who face poverty and other barriers to support, safety and justice. If we get it right for those who are most marginalised and discriminated against by systems and services, we will get it right for all

- build a sustainable, diverse, and collaborative organisation, with the capabilities and expertise required to effectively lead and facilitate transformational change across policy, the service system and our community

- collaborate with specialist partner agencies and ensuring that where reforms focus on preventing and responding to Aboriginal people who experience family violence, that this work be led by Aboriginal communities and services

- commit to Aboriginal self-determination, anti-racist and anti-discriminatory practice

- value the expertise of people with lived experience of family violence and sexual violence, and to working in partnership and to advocating and embedding intersectionality to achieve inclusion and equity when delivering our priorities

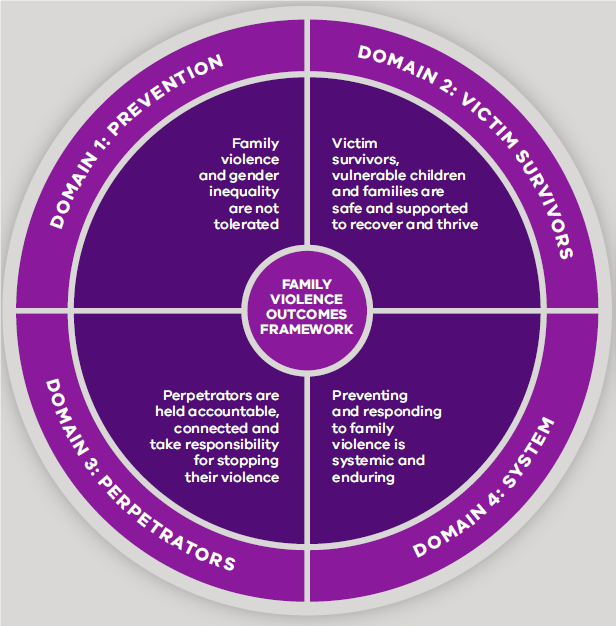

- align with the state’s Family Violence Outcomes Framework.

Strategic priority 1

Victim survivors, children and families are safe and supported to recover and thrive.

This priority contributes to whole of government efforts to ensure early intervention prevents escalation and that victim survivors are safe, heard and in control.

To achieve this, we will support victim survivors, children and young people and families to access support where and when it is required, and in ways that meet their individual and diverse needs.

We will support young people who use violence to meet their needs and change their behaviour. We will also implement best practice frameworks across family violence, sexual violence, child and family services statewide, without limiting local responsiveness and accountability.

In partnership with our stakeholders, our work plans will prioritise:

- Designing and supporting delivery of new and improved service models and person-centred supports.

- Identifying appropriate services for children and young people requiring support and responding to service gaps for children and young people requiring family violence-related support.

- Expanding the Adolescent Family Violence Program and other specialist therapeutic programs for victim survivors of family violence statewide.

- Ensuring improved responses to multicultural communities (including refugee, migrant and cultural and linguistically diverse communities) in need of family violence and sexual violence support and support to increase children and young people’s wellbeing.

- Rolling out The Orange Door network statewide.

- Improving refuge services, including via the capital redevelopment program.

- Strengthening frontline services for Aboriginal people through Aboriginal-led responses.

- Conducting an analysis of the system-level housing requirements at each stage of a victim survivor’s journey, including children and young people, and identifying person-centred solutions.

- Improving the experiences of victim survivors who are housed in crisis accommodation, while seeking more appropriate and sustainable options.

Strategic priority 2

Perpetrators are held accountable, connected and take responsibility for stopping their violence.

This priority contributes to whole of government efforts to ensure perpetrators stop all forms of family violence behaviour and are held accountable.

To achieve this we will enable services and programs to be more effective at engaging perpetrators, holding them accountable and helping them change behaviour.

In partnership with our stakeholders, our work plans will prioritise:

- Overseeing and supporting the continuous improvement of established, new and improved interventions and services for perpetrators.

- Developing and delivering a system-wide approach to keeping perpetrators accountable, connected and responsible for stopping their violence

- Continuing the Central Information Point model to provide information about perpetrators in support of effective risk management

- Strengthening perpetrator accountability systems to support victim survivors to safely remain in their own homes, and consider ongoing options to support removing perpetrators from homes.

- Reviewing the effectiveness of Risk Assessment and Management Panels’ management of highest risk perpetrators, to connect the growing approaches to perpetrator management across the system.

- Applying lessons from the evidence base, to inform improvement and design of interventions for people who use violence. This includes people with multiple and complex needs, Aboriginal communities, people from culturally diverse communities and people who are LGBTIQ.

- Promoting learning from the holistic approach taken from working with Aboriginal men who use violence to document whole-of-family practice in working with people who use violence and develop holistic healing practice guidance and training for mainstream service providers, in line with Nargneit Birrang.

Strategic priority 3

System change: preventing and responding to family violence is systemic and enduring.

This priority contributes to whole of government efforts to ensure the family violence system:

- is accessible, integrated, available and equitable

- intervenes early to identify and respond

- is person-centred and responsive and uses a trauma-informed approach

- is supported by skilled, capable workforces that reflect the communities they serve.

To achieve this, we will provide adequate support and resourcing to family violence, sexual assault, child and family services and programs, to make them more sustainable and so that they have the capability and capacity to deliver high quality and effective services that better meet demand.

We will work with our stakeholders to ensure that the family violence and sexual violence workforces are healthy and safe, engaged and supported to collaborate, learn and develop.

We will enable multi-agency collaboration to increase the rates and effectiveness of identifying and meeting people’s needs and to enhance risk management and reduction. We will also support the safe sharing of information across the system at the right time, in line with required schemes, to help prevent further violence, keep victim survivors safe and hold perpetrators accountable.

Reform governance and impact

In 2020, a refreshed Family Safety Victoria governance model was introduced to support the next implementation phase of family violence reforms. It was designed to provide system-wide oversight, strategic leadership and flexible engagement and brought together experts to leverage their knowledge, insights and advice across the system.

Family Safety Victoria’s governance model comprises:

The Family Violence Reform Advisory Group

This Family Violence Reform Advisory Group advises government on system-level impacts of the family violence reforms and makes recommendations to achieve an improved whole-of-system approach to prevention and response.

It includes membership representing:

- the family violence sector

- service delivery (such as workforce, housing legal, prevention and inclusion and equity)

- government departments or agencies

- VSAC

- the Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum.

Family Violence Reform Advisory Board

This Family Violence Reform Advisory Board provides governance advice on specific issues, endorses changes, provides strategic direction and decision making for the delivery of Family Safety Victoria’s key reforms.

It includes membership representing government departments or agencies:

- Family Safety Victoria

- Department of Families

- Fairness and Housing

- Department of Health

- Department of Justice and Community Safety

- Department of Education and Training

- Department of Premier and Cabinet

- Department of Treasure and Finance

- Victoria Police

- the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria.

A number of working groups are also in place to ensure targeted advice is provided on reform and implementation areas.

Our effectiveness is measured against the government’s Family Violence Outcomes Framework, which was co-developed with the family violence service delivery sector, people with lived experience and community members.

Focusing on data and an evidence-based approach means we are better informed about:

- performance and progress

- community needs and demand

- the capacity of the wider system

- what works to prevent violence and meet the needs of children young people and families.

We also ensure our work and program development is monitored and evaluated.

For example, the MARAM monitoring and evaluation framework provides indicators to determine whether the MARAM reform is contributing to victim survivor safety, perpetrator accountability and earlier intervention. It will be used to gather regular monitoring data, as well as to inform the legislated 5-year review of MARAM and the family violence information sharing scheme.

The Dhelk Dja partnership has also agreed a Monitoring, Evaluation and Accountability (MEA) Plan, to accompany the Aboriginal 10-year Family Violence Agreement 2018-2028. The Plan lays out how the Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum can monitor and evaluate its strategy, including whether the Dhelk Dja agreement is achieving its intended outcomes.

The outcomes, indicators and measures in the MEA Plan are Aboriginal defined measures of progress and success that align with holistic understandings of health and wellbeing and were developed with the Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum in line with the Victorian government’s commitment to Aboriginal self-determination.

Family Safety Victoria reports against the following reporting mechanisms:

| Reporting mechanism | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Family Violence Outcomes Framework Annual Report, which measures progress against outcomes and indicators across government | Annual |

| Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor, which independently assesses progress to implement the Royal Commission recommendations | Annual |

| Formal acquittal of Royal Commission into Family Violence recommendations and corresponding updates to the public-facing website | Bi-annual |

| Departmental annual report, which includes the results of agreed performance measures against a range of family violence and sexual assault budgetary initiatives | Annual |

| The Orange Door service delivery report, which summarises service delivery outcomes via The Orange Door for a specified financial year | Annual |

| MARAM Annual Report, which outlines the implementation and operation of the approved Family Violence Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM) and is tabled in Parliament as a legislative requirement | Annual |