- Date:

- 24 Feb 2023

Acknowledgements

Aboriginal acknowledgement

The Victorian Government acknowledges Victorian Aboriginal people as the First Peoples and Traditional Owners and Custodians of the land and water on which we rely. We acknowledge and respect that Aboriginal communities are steeped in traditions and customs built on a disciplined social and cultural order that has sustained 60,000 years of existence. We acknowledge the significant disruptions to social and cultural order, and the ongoing hurt caused by colonisation.

We acknowledge the ongoing leadership role of Aboriginal communities in addressing and preventing family violence and will continue to work in collaboration with First Peoples to eliminate family violence from all communities.

Recognition of victim survivors

The Victorian Government acknowledges victim survivors and honours their resistance and resilience. We keep at the forefront in our minds all those who have experienced family violence or other forms of abuse, and for whom we undertake this work.

Family violence support

If you have experienced violence or sexual assault and require immediate or ongoing assistance, contact 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) to talk to a counsellor from the National Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence hotline.

For confidential support and information, contact the Safe Steps 24/7 family violence response line on 1800 015 188.

If you are concerned for your safety or that of someone else, please contact the police in your state or territory, or call Triple Zero (000) for emergency assistance.

Message from the Minister for Prevention of Family Violence

I would like to present the fifth annual report on the continued roll-out of the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) Framework 2022–23.

This report details the implementation progress and achievements departments, peak bodies, agencies and organisations in aligning their procedures, policies and practice guidance to MARAM.

In January 2023, the Victorian Government announced the implementation of all 227 recommendations of the Royal Commission into Family Violence to reduce the impact of family violence in Victoria.

The MARAM Framework (established in 2018 and embedded into the Family Violence Protection Act 2008) is a critical part of Victoria’s family violence reform and ensures that responding to family violence becomes a collective, system-wide responsibility.

Since the Royal Commission, the Victorian Government has invested more than $3.86 billion to prevent and respond to family violence, which includes $97 million in 2021–22 over 4 years to keep people safer, implementing MARAM reform and alignment activities, as well as critical information-sharing reform. Key achievements demonstrate that this investment is making a difference.

In October 2023, the 5-year MARAM legislative review was completed. This external analysis included recommendations to ensure family violence risk factors are appropriately reflected in MARAM Framework practice guidance and tools.

In 2022–23, more than 100,000 professionals across a range of sectors and the continuum of services received training in or aligned to MARAM and the associated information sharing schemes.

More than 200,000 workers have been trained since 2018, bringing Victoria closer to the target of 370,000 trained professionals. More than 40,000 risk assessments and safety plans have been undertaken (using MARAM online tools), and more than 20,230 Central Information Point reports have been delivered.

Driving lasting change is demanding, and we still have a lot of work to do. Departments, workforces and community services are committed to an effective family violence system.

By continuing alignment to MARAM and embracing collaboration in the response to family violence risk, we ensure better outcomes for the community.

I would like to express my gratitude to past and present ministers responsible for framework organisations in their portfolios for their sustained efforts in advancing this essential reform. This report is consolidated from my own portfolio report and those provided to me by:

- The Hon. The Hon. Anthony Carbines MP, Minister for Police, Minister for Crime Prevention

- The Hon. Colin Brooks MP, former Minister for Housing Minister for Multicultural Affairs

- The Hon. Danny Pearson MP, former Minister for Consumer Affairs

- The Hon. Enver Erdogan MLC, Minister for Corrections, Minister for Victim Support, Minister for Youth Justice

- The Hon. Ingrid Stitt MLC, former Minister for Early Childhood and Pre-Prep, Minister for Mental Health, Minister for Ageing, Minister for Multicultural Affairs

- The Hon. Jaclyn Symes MLC, Attorney General

- The Hon. Lizzie Blandthorn MLC, Minister for Children, Minister for Disability

- The Hon. Mary-Anne Thomas, Minister for Health, Minister for Ambulance Services

- The Hon. Natalie Hutchins MP, former Minister for Education.

I would like to thank Family Violence Regional Integration Committees, peak bodies, Aboriginal community-controlled organisations, and many others, such as multicultural community organisations and services who contribute tirelessly to the success of MARAM practice.

I would also like to thank specialist family violence services (including sexual assault services) and The Orange Door network for their passionate work and partnership. Your work is part of the foundation of our family violence system.

To those with lived experience, including past and present members of the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council, your voices guide us in shaping MARAM practice and making a difference in the lives of those affected by family violence.

I would like to thank all government and sector collaborators who have contributed to this report for their dedication to victim survivors and the future of family safety and wellbeing in Victoria. Our communities want to feel safe, and the work we do continues to progress safety for all.

Vicki Ward MP

Minister for Prevention of Family Violence

Minister for Employment

Introduction

The Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) Framework was established in legislation in 2018. It responds to the first two recommendations of Victoria’s Royal Commission into Family Violence 2016 (the Royal Commission).

The MARAM Framework creates a system-wide model for all services that interact with adults and children who have experienced family violence or may be at risk of experiencing family violence.

It covers all aspects of service delivery. This includes early risk identification, screening, assessment and management, safety planning, collaborative practice, stabilisation and recovery.

The MARAM Framework aims to:

- ensure all professionals, regardless of their role, have a shared understanding of family violence and perpetrator behaviour

- increase the safety of people experiencing family violence

- ensure the broad range of experiences are represented in the family violence response. This includes for Aboriginal and diverse communities and identities, children, young people, older people, and different family and relationship types

- keep perpetrators in view and hold them accountable for their actions

- provide guidance to organisations on aligning to the Framework to ensure consistent service delivery.

MARAM is being implemented alongside two other enabling reforms for information sharing and risk frameworks– the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS) and the Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS). Family Safety Victoria is the lead agency on the implementation of MARAM and the FVISS. The Department of Education (DE) is the lead agency on the implementation of the CISS.

Organisations are prescribed under the regulations as MARAM Framework organisations and/or Information Sharing Entities (ISEs).

Section 193 of the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic) requires a report to be tabled in parliament annually on the progress of MARAM implementation. This is the fifth report to be tabled, covering implementation activities from 1 July 2022 to 30 June 2023.

Family Safety Victoria, a Division of the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (the department), leads the implementation of the reforms. This requires Family Safety Victoria to design and develop the policies, resources and training and prepare this consolidated annual report. Family Safety Victoria also oversees implementation across the whole of the Victorian Government (WoVG) through governance, reporting and annual surveys and for the department across its various workforce portfolios.

Each relevant department is responsible for tailoring the policies, resources and training to their specific workforce needs. This includes communication about the reforms and responses to barriers the workforces face.

Sector peak and representative organisations support implementation more directly with practitioners. In 2022–23, the department funded 16 organisations to undertake this work through the Sector Capacity Building Grants program. The funded organisations are:

- Adult Multicultural Education Services (AMES)

- Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare (CFECFW)

- Council to Homeless Persons

- Dardi Munwurro

- Djirra

- Elizabeth Morgan House

- Jewish Care Victoria

- No to Violence (NTV)

- Safe and Equal

- Sexual Assault Services Victoria

- Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA)

- Victorian Aboriginal Community Services Association Limited (VACSAL)

- Victorian Alcohol and Drug Association (VAADA)

- Victorian Healthcare Association (VHA)

- Whittlesea Community Connections (WCC)

- Youth Justice.

Chapters 1 to 4 of this report provide context of the reforms, legislation, and relevant portfolios.

Chapter 5 provides an overview of the current state of WoVG MARAM alignment, as indicated by the 2023 MARAM Annual Survey.

Chapters 6 to 9 cover the four WoVG strategic priorities. A chapter is dedicated to each priority.

- clear and consistent leadership

- supporting consistent and collaborative practice

- building workforce capability

- reinforcing good practice and commitment to continuous improvement.

Each chapter contains subsections related to work undertaken by:

- Family Safety Victoria within the Department of Families Fairness and Housing as reform lead

- departments as leads for their workforces

- sector peak bodies and organisations that support practitioners.

Whole of government snapshot

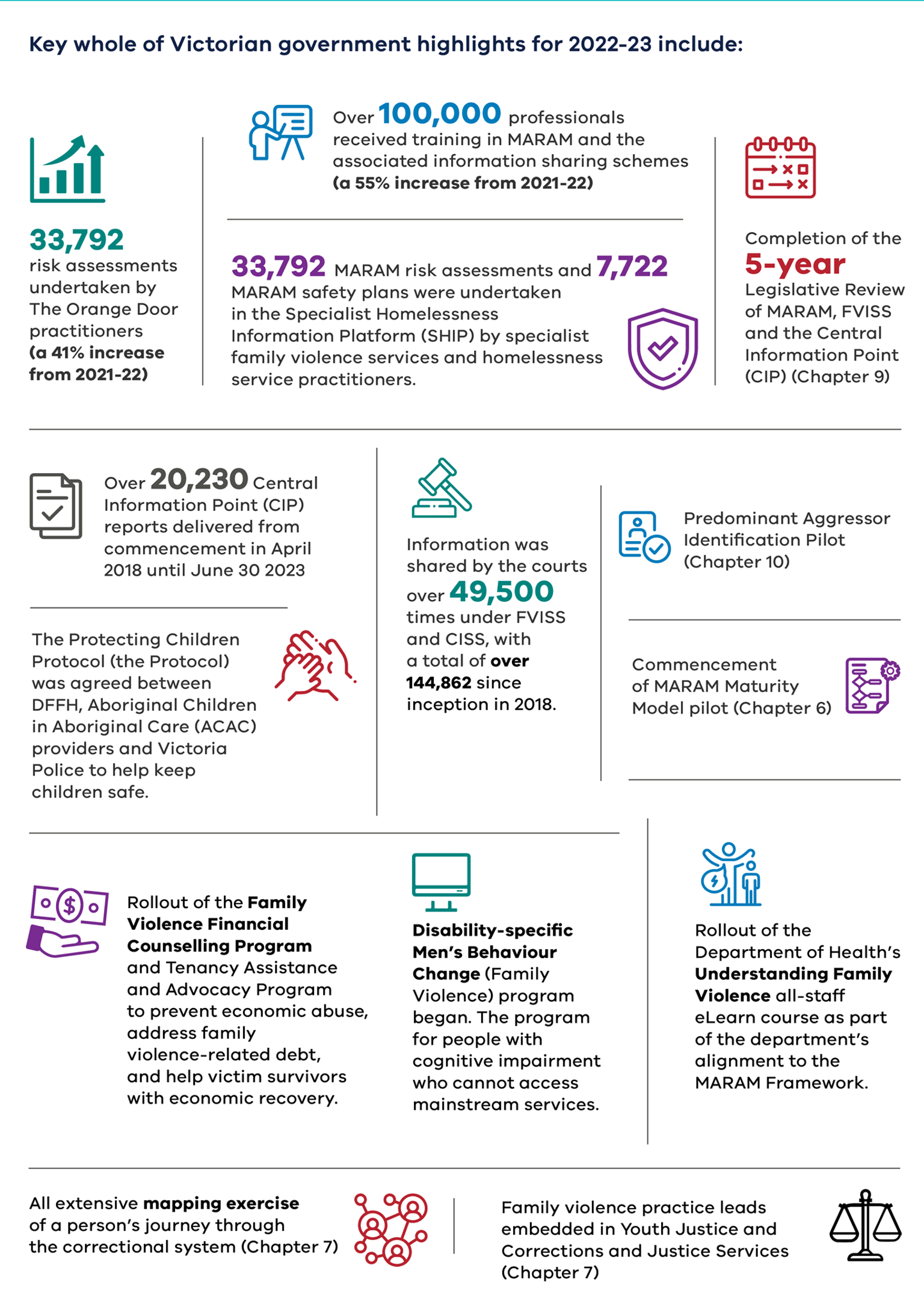

Key whole of Victorian Government highlights for 2022–23 include:

- 33,792 MARAM risk assessments undertaken by Tools for Risk Assessment and Management (TRAM) (a 41% increase from 2021-22). TRAM is used by practitioners in the Orange Door and a select number of specialist family violence and generalist agencies for risk assessment and safety planning

- Over 100,000 professionals received training in MARAM and the associated information sharing schemes (a 55% increase from 2021–22). Over 12,000 Victoria Police staff completed training, and over 81,000 training units were undertaken by Department of Health workforces

- 41,231 MARAM risk assessments, and 7,722 MARAM safety plans were undertaken in the Specialist Homelessness Information Platform (SHIP) by specialist family violence services and homelessness service practitioners.

- Over 20,230 Central Information Point (CIP) reports delivered from commencement in April 2018 until 30 June 2023

- Information shared by the courts over 49,500 times under the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS) and the Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS), with a total of over 144,862 since inception in 2018

- Completion of the 5-year Legislative Review of MARAM, FVISS and the CIP (Chapter 9)

- The commencement of Victoria Police’s Predominant Aggressor Identification pilot (Chapter 10)

- The commencement of MARAM Maturity Model pilot (Chapter 6)

- The Protecting Children Protocol (the Protocol) updates agreed between DFFH, Aboriginal Children in Aboriginal Care (ACAC) providers and Victoria Police to align to MARAM

- Commencement of the Disability-specific Men’s Behaviour Change (Family Violence) program. The program is aimed at perpetrators with cognitive disability who face barriers in accessing mainstream family violence and support services

- The rollout of the Department of Health’s Understanding Family Violence all-staff eLearn course as part of the department’s alignment to the MARAM Framework

- The rollout of Family Violence Financial Counselling Program and Tenancy Assistance and Advocacy Program to prevent economic abuse, address family violence-related debt, and help victim survivors with economic recovery. 3,806 victim survivors of family violence accessed financial counselling in 2022-23 through the Family Violence Financial Counselling Program

- An extensive mapping exercise of a person’s journey subject to Community Correctional Services (CCS) supervision or custody to understand how and when MARAM will be implemented and integrated into the corrections system (Chapter 7)

- Family violence practice leads embedded in Youth Justice and Corrections and Justice Services (Chapter 7).

Chapter 1: Portfolios

This table sets out the departments, ministers, portfolios and program areas that are referenced in this report.

See Appendix 6 for a more detailed description of each program area's work profile.

Table 1: Ministers, portfolios, and responsibilities for the 2022–23 reporting period.

| Minister | Portfolio | Responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| The Hon. Ros Spence MP | Minister for Prevention of Family Violence |

|

| The Hon. Anthony Carbines MP | Minister for Police Minister for Crime Prevention |

|

| The Hon. Colin Brooks MP | Minister for Housing Minister for Multicultural |

|

| The Hon. Danny Pearson MP | Minister for Consumer Affairs |

|

| The Hon. Enver Erdogan MLC | Minister for Corrections Minister for Victim Support Minister for Youth Justice |

|

| The Hon. Gabrielle Williams MP | Minister for Ambulance Services Minister for Mental |

|

| The Hon. Ingrid Stitt MLC | Minister for Early Childhood and Pre-Prep |

|

| The Hon. Jaclyn Symes MLC | Attorney-General |

|

| The Hon. Lizzie Blandthorn MLC | Minister for Child Protection and Family Services Minister for Disability |

|

| The Hon. Mary-Anne Thomas | Minister for Health |

|

| The Hon. Natalie Hutchins MP | Minister for Education |

|

Chapter 2: Language used in this report

Adults, children and young people who have experienced family violence are referred to as victim survivors. We note that some people also prefer to use the term people who experience violence.

The word family has many meanings. This report uses the definition from the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (the Act). This acknowledges the variety of relationships and structures that can make up a family unit, and the range of ways family violence can be experienced, including through family-like or carer relationships (in non-institutional paid carer environments).

The term family violence reflects the Act and includes the wider understanding of the term across all communities. Dhelk Dja: safe our way – strong culture, strong peoples, strong families[1] defines family violence as an issue relating to physical, emotional, sexual, social, spiritual, cultural, psychological and economic abuses. These occur within families, intimate relationships, extended families, kinship networks and communities. It extends to one-on-one fighting and abuse of Indigenous community professionals, as well as self-harm, injury and suicide.

Throughout this document, the term Aboriginal is used to refer to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Intersectionality describes how systems and structures interact on multiple levels to oppress, create barriers and overlapping forms of discrimination, stigma and power imbalances. It is based on characteristics such as Aboriginality, gender, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, ethnicity, colour, nationality, refugee or asylum seeker background, migration or visa status, language, religion, ability, age, mental health, socioeconomic status, housing status, geographic location, medical record or criminal record. This compounds the risk of experiencing family violence and creates additional barriers for a person to access the help they need.

The term perpetrator describes adults who choose to use family violence, acknowledging the preferred term for some Aboriginal people and communities, as well as in practice, is a person who uses violence. The perpetrator is also the predominant aggressor where misidentification is suspected or has been assessed as occurring.

Young people who use family violence require a different response to adults who use family violence, because of their age, developmental stage and the possibility that they are also victim survivors of family violence. The term perpetrator is not used to refer to young people who use family violence. Some programs refer to adolescents who use family violence in the home.

References

[1] Dhelk Dja: safe our way is an Aboriginal-led agreement to address family violence in Victorian Aboriginal communities.

Chapter 3: Legislation and regulations

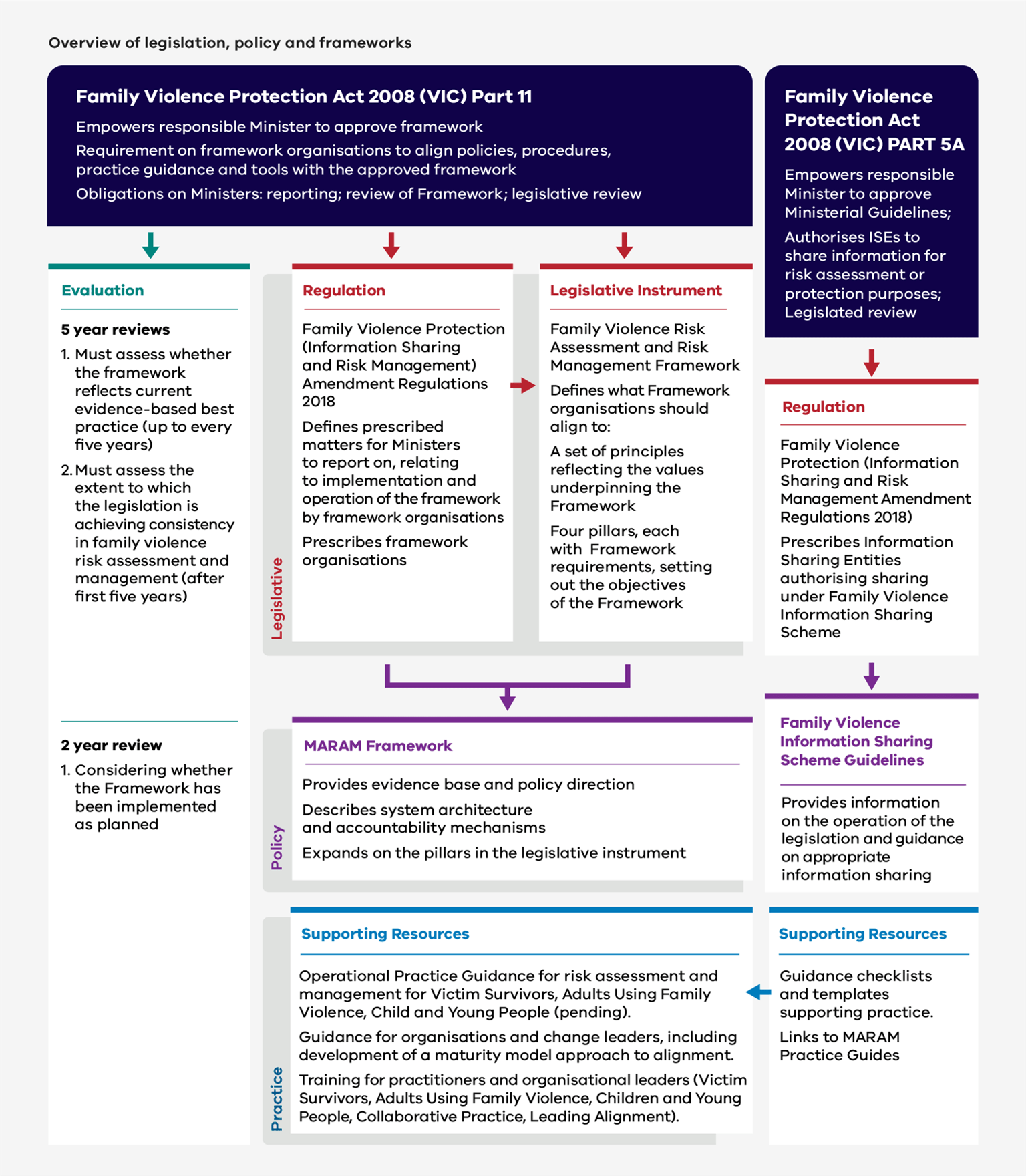

The legislative structure around MARAM is shown in Figure 2.

Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (VIC) Part 11

- Empowers responsible Minister to approve framework

- Requirement on framework organisations to align policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools with the approved framework

Obligations on Ministers: reporting; review of Framework; legislative review

Evaluation

5 year reviews

- Must assess whether the framework reflects current evidence-based best practice (up to every five years)

- Must assess the extent to which the legislation is achieving consistency in family violence risk assessment and management (after first five years)

2 year review

- Considering whether the Framework has been implemented as planned.

Legislative

Regulation

Family Violence Protection (Information Sharing and Risk Management) Amendment Regulations 2018.

- Defines prescribed matters for Ministers to report on, relating to implementation and operation of the framework by framework organisations

- Prescribes framework organisations.

Legislative instrument

Family Violence Risk Assessment and Risk Management Framework.

Defines what Framework organisations should align to:

- A set of principles reflecting the values underpinning the Framework

- Four pillars, each with Framework requirements, setting out the objectives of the Framework.

Policy

MARAM Framework

- Provides evidence base and policy direction

- Describes system architecture and accountability mechanisms

- Expands on the pillars in the legislative instrument

Practice

Supporting resources

- Operational Practice Guidance for risk assessment and management for Victim Survivors, Adults Using Family Violence, Child and Young People (pending).

- Guidance for organisations and change leaders, including development of a maturity model approach to alignment.

- Training for practitioners and organisational leaders (Victim Survivors, Adults Using Family Violence, Children and Young People, Collaborative Practice, Leading Alignment).

Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (VIC) PART 5A

- Empowers responsible Minister to approve Ministerial Guidelines;

- Authorises ISEs to share information for risk assessment or protection purposes;

- Legislated review

Legislative

Regulation

Family Violence Protection (Information Sharing and Risk Management Amendment Regulations 2018)

- Prescribes Information Sharing Entities authorising sharing under Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme.

Policy

Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme Guidelines

Provides information on the operation of the legislation and guidance on appropriate information sharing.

Practice

Supporting resources

- Guidance checklists and templates supporting practice.

- Links to MARAM Practice Guides

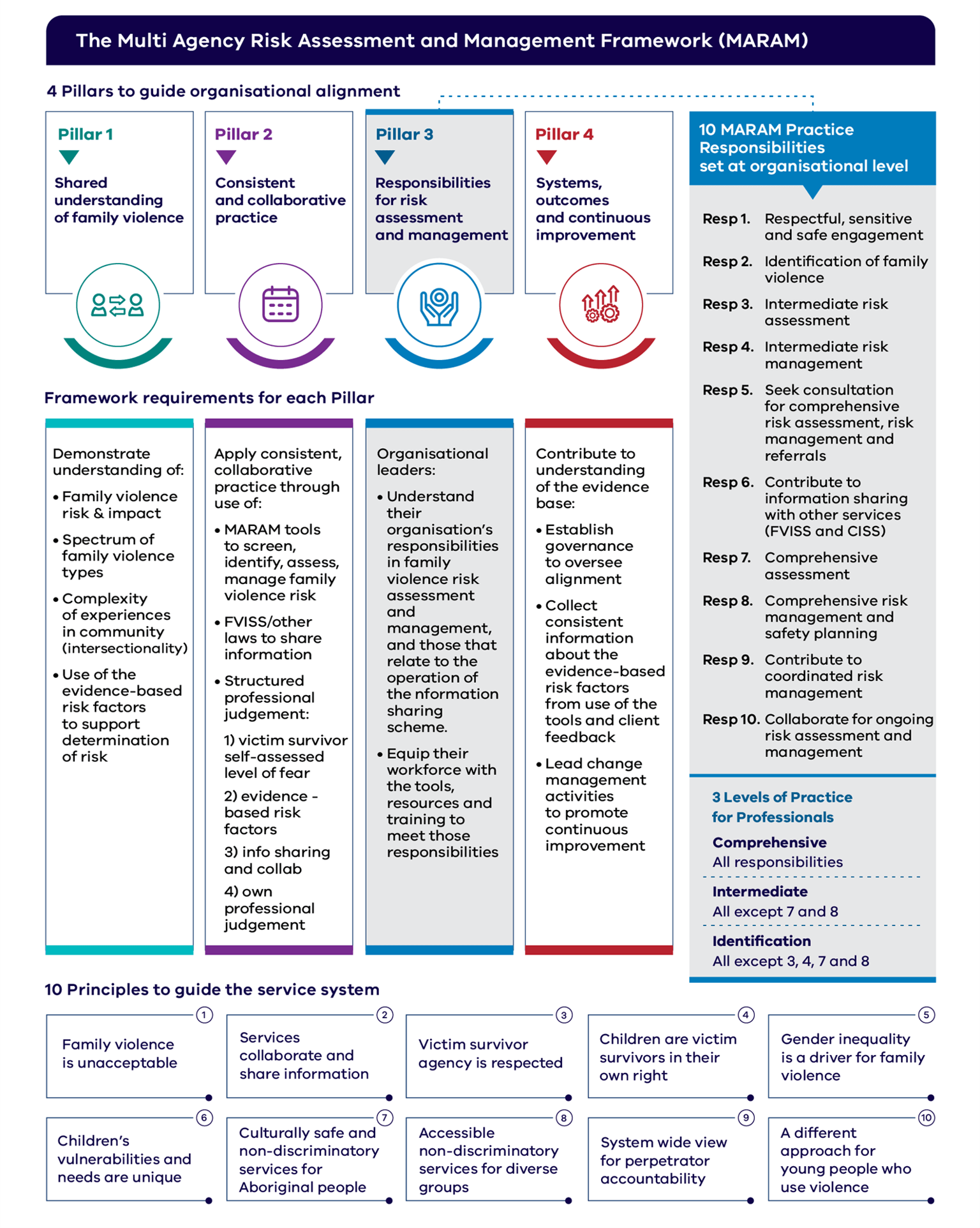

Chapter 4: MARAM structure

The three core components of MARAM are illustrated in Figure 3 below. The MARAM pillars are set at an organisational level. They each contain a requirement to which organisations must align. Alignment is defined as actions taken by organisations to effectively incorporate the four pillars into existing policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools, as appropriate to the roles and functions of the entity and its place in the service system. Appendix 3 sets out the MARAM pillars.

The pillars, along with 10 MARAM principles guide a shared understanding of family violence response across the service system to guide consistent practice. Appendix 4 provides the full text of the principles.

The MARAM responsibilities set out the practice expectations for professionals in relation to family violence risk identification, assessment and management. Supporting resources provides guidance for organisations to determine the appropriate MARAM responsibilities for their workforce. Appendix 5 provides the full details of the responsibilities.

The responsibilities can be broadly summarised into three levels of practice:

- identification – this role incorporates all MARAM responsibilities, except those related to assessment and management of risk (3–4 and 7–8). It applies to people who interact with Victorians in the course of their work, where they could identify family violence is taking place. They may be able to observe family violence narratives or behaviours, and/or ask sensitive questions of victim survivors (for example, at schools and early childhood centres)

- intermediate – this role incorporates all MARAM responsibilities, except specialist risk assessment and management (7–8). It applies to people who interact with Victorians in the course of their work, where they can assess or manage a presenting ‘need’ (for example, alcohol or drug use, mental health or housing crisis)

- comprehensive – this role incorporates all 10 MARAM responsibilities. It applies to people who interact with Victorians in a specialist capacity to directly respond to family violence (for example, specialist family violence services and family violence refuges).

Chapter 5: MARAM Framework Annual Survey

Family Safety Victoria conducts an annual survey of framework organisations. The survey seeks to understand:

- the progress of implementation across different sectors

- how sectors can be supported to keep improving MARAM implementation.

Family Safety Victoria released the third annual MARAM Framework survey during this reporting period.

Across sectors

The survey was completed by 361 organisational leaders engaged in MARAM implementation activities across multiple sectors. It represents more than 600 MARAM-prescribed workforces and services.

The response in 2022–23 rate is 49 per cent higher than the previous year. This is mostly due to much higher engagement from leaders in the health sector.

Demographics

Most respondents are employed in health (42 per cent) and human services (26 per cent). They come from large or medium size organisations that provide metropolitan, metropolitan wide and/or state-wide services. 74 per cent of surveyed leaders are involved in policy, practice, and capacity development. Representation from the education and justice workforces was limited.

Supports received

Leaders indicated their organisations have received a variety of supports, communications, and training from Family Safety Victoria and departments to assist with MARAM alignment:

- 49 per cent stated they have received organisational supports from Safe and Equal

- 66 per cent have received accredited MARAM training

- 51 per cent have completed eLearns (identification and intermediate)

- 46 per cent have attended facilitated non-accredited MARAM training.

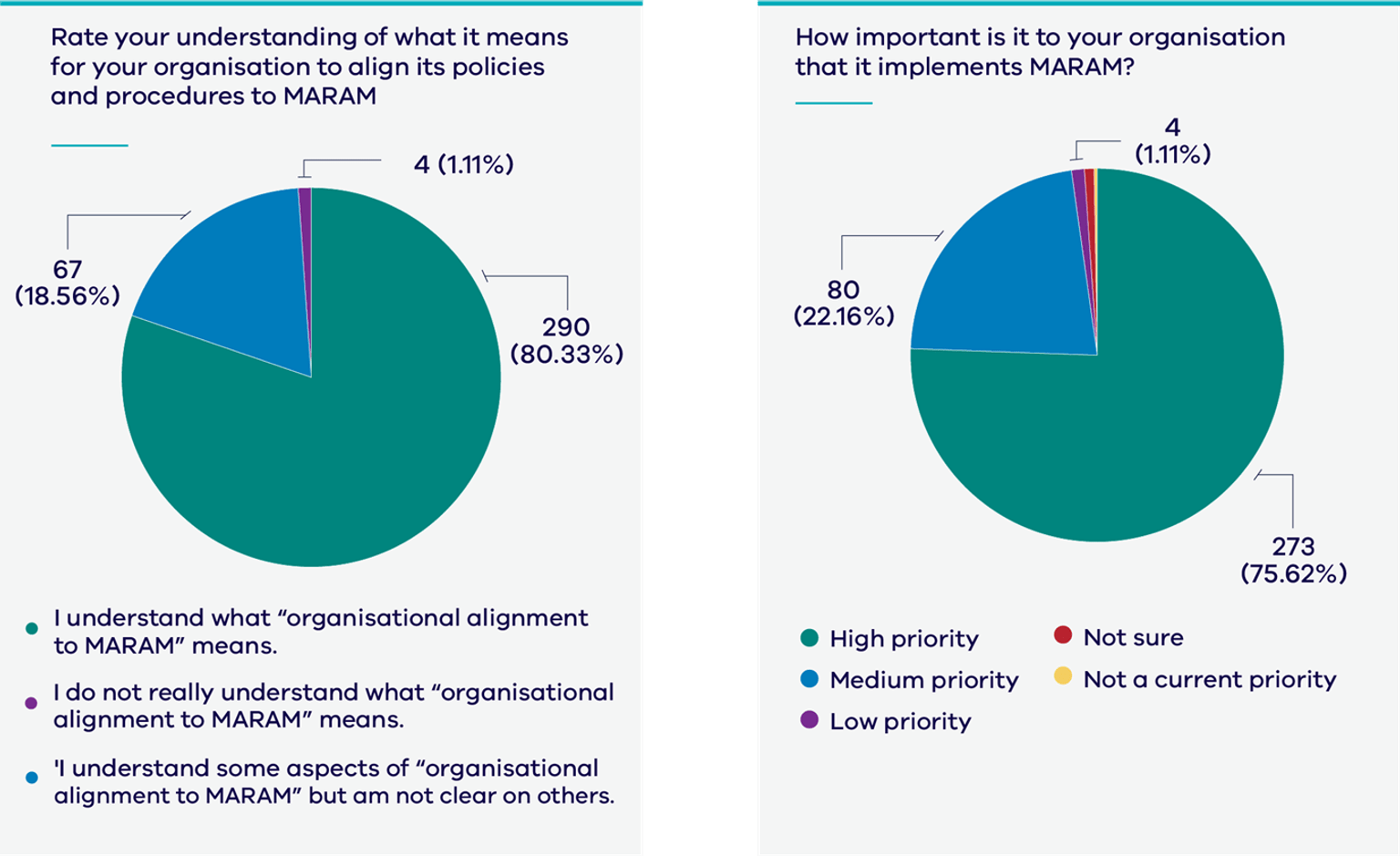

Most leaders (more than 90 per cent) also reported an understanding of obligations and responsibilities under MARAM and assessed MARAM alignment to be a high priority in their organisation (Figure 4).

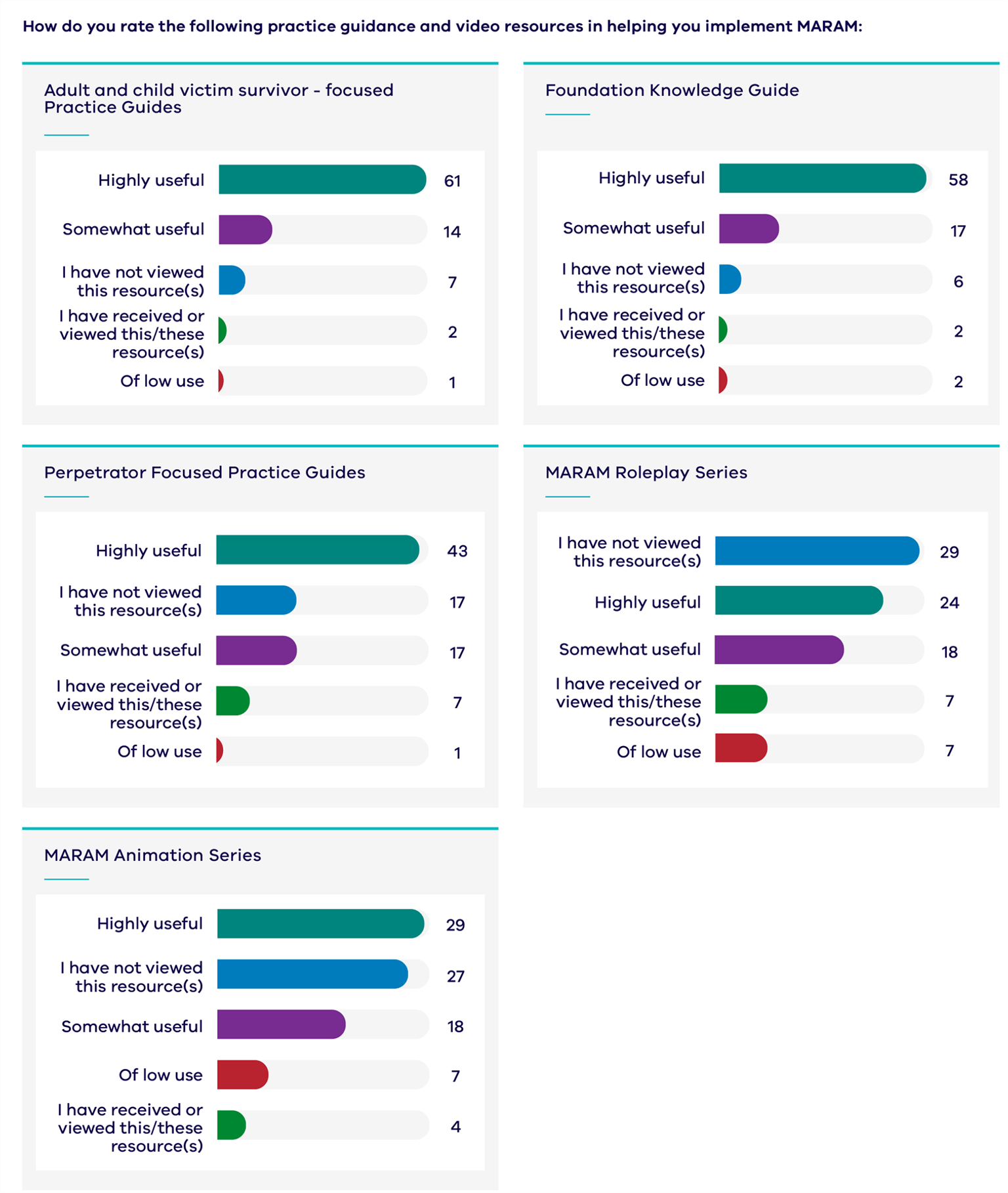

Key organisational resources for MARAM, FVISS and CISS alignment appear to be considered useful, while some leaders are unaware of some newer or supportive materials.

Regarding internal organisational supports for alignment, most respondents agreed or strongly agreed that:

- they have been supported (88 per cent)

- organisational culture supports alignment (90 per cent)

- there is clear MARAM alignment leadership (79 per cent).

However, 15 per cent disagreed that there are effective continuous improvement processes, and 13 per cent disagreed that there is visible leadership and accountability.

Alignment progress

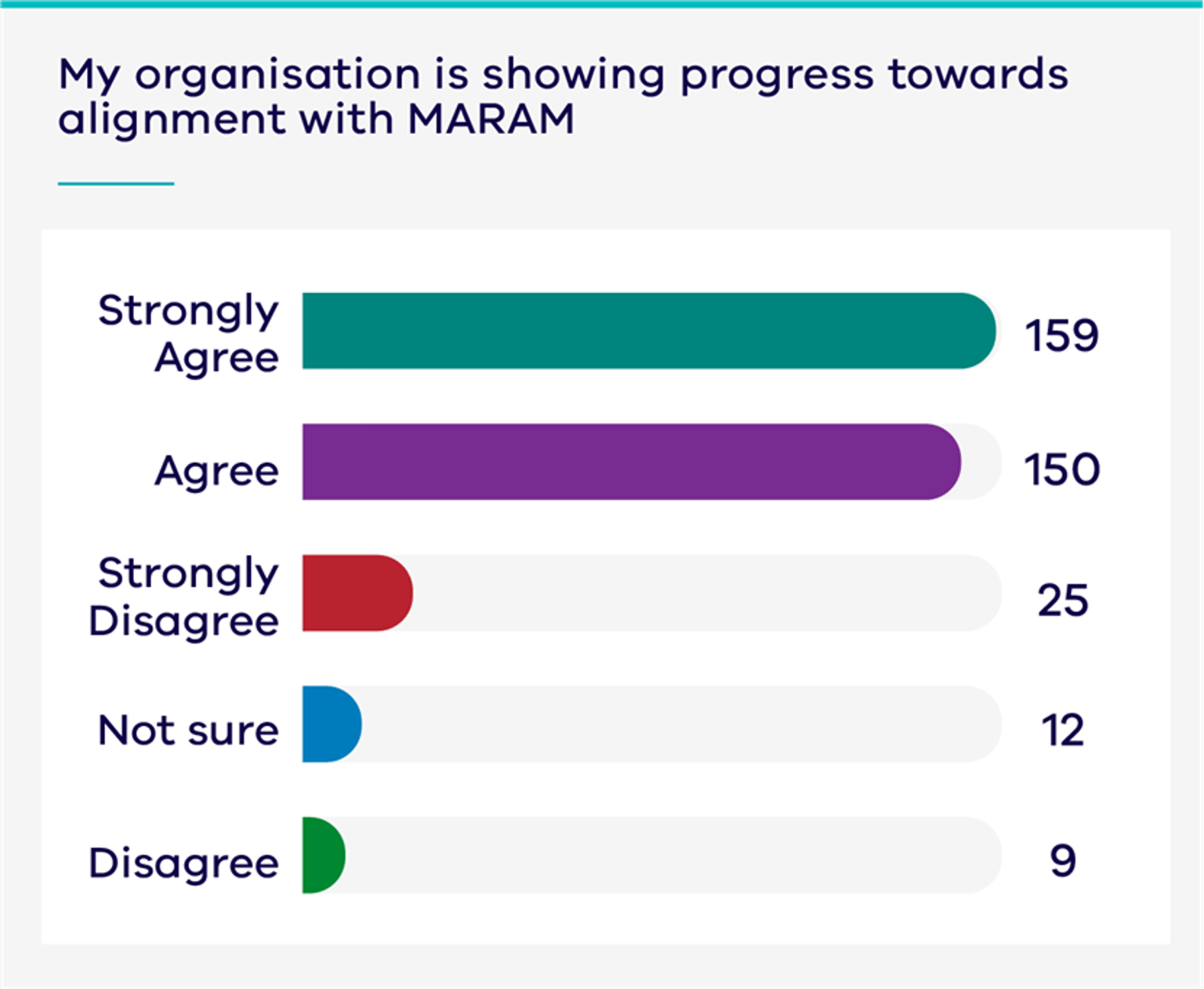

The great majority of respondents (87 per cent) agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that ‘their organisation is showing progress towards alignment with MARAM’.

Most respondents (80 per cent) reported that their organisations either ‘have or are creating/adapting a change management plan for implementing MARAM’. However, 20 per cent of respondents reported no change management plan for MARAM implementation.

Pleasingly, 100 per cent of ACCOs (33 respondents) reported either ‘having or have created/adapting a change management plan for implementing MARAM’. Additional findings include:

- 78 per cent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that ‘professionals in their organisation understand information sharing responsibilities’

- 90 per cent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that ‘professionals in their organisation are aware of MARAM’

- 88 per cent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that ‘professionals in their organisation are aware of victim survivor and perpetrator referral services’.

Challenges

Respondents were also asked about MARAM alignment challenges. The most common theme across responses was a lack of time and resources.

Specialist services

Of the 361 responses to the survey, 85 respondents reported working in a state-funded specialist family violence or sexual assault service.

Demographics

The 85 specialist leaders that responded to the survey are employed in the human services and ACCO sectors and mostly come from large or medium size organisations that provide state-wide and metropolitan services. 84 per cent of these leaders are ‘always involved’ in policy, practice and capacity development.

Supports received

Specialist leaders and their organisations have received a variety of supports, communications and training. 80 per cent of respondents indicate having received organisational supports from Safe and Equal. 68 per cent of respondents indicate their organisations having received accredited MARAM training, 55 per cent indicate attendance of non-accredited MARAM training and 47 per cent attendance of Leading Alignment Training.

All (100 per cent) leaders reported having an ‘understanding of obligations and responsibilities under MARAM’ and most (99 per cent) place alignment as a high or medium priority. Practice guidance for MARAM appears to be considered highly or somewhat useful (more than 70 per cent of respondents), with some leaders not having viewed the roleplay and animation series.

Most respondents agree or strongly agree that they have been internally supported (95 per cent), organisational culture supports alignment (94 per cent), there is clear alignment leadership (90 per cent), there are continuous improvement processes (85 per cent), processes that enable MARAM responsibilities (98 per cent), and the organisation is prepared and supported to align (93 per cent).

Alignment progress

The great majority of respondents (91 per cent) agree or strongly agree with the statement that their organisation is ‘showing progress towards alignment with MARAM’.

The greater proportion of respondents (89 per cent) report that their organisations either have or are creating/adapting a change management plan for implementing MARAM.

Most respondents seem to agree or strongly agree that they have been supported (95 per cent), organisational culture supports alignment (94 per cent), and that there is clear alignment leadership (90 per cent).

Table 2 demonstrates that the majority of specialist service leaders appear to have taken the key foundational and intermediate steps for organisational alignment, while it does appear that more advanced alignment activities are still in progress.

Challenges

Lack of staff time and lack of resources were flagged by respondents as key challenges to alignment.

Table 2: WoVG alignment: Activities that you and/or your organisation has undertaken to align to MARAM

| Activity | Percent |

|---|---|

| Read the MARAM Framework and/or any other available MARAM supporting materials, guides and other reference documents provided by FSV and/or your funding departments | 80 |

| Considered the impact of MARAM on your organisation’s day-to-day operations | 78 |

| Commenced updating and/or creating new policies, procedures, practice guidelines to align with MARAM | 75 |

| Commenced updating and/or creating new tools and forms to align with MARAM | 74 |

| Established a group or identified an individual within your organisation to oversee and support the implementation of MARAM | 72 |

| Identified or supported relevant professionals to attend MARAM training delivered by Safe & Equal, your funding department or other service-specific family violence training | 69 |

| Identified any changes that will be required to current client or patient information gathering, documentation, storage and reporting to enable organisational alignment with MARAM | 68 |

| Implemented or updated a family violence referral protocol, agreement or guideline to align with MARAM | 66 |

| Determined which MARAM responsibilities apply to which professionals in your organisation and communicated this to relevant staff | 65 |

| Identified opportunities for greater collaboration with agencies in your local area for assessing and managing family violence risk | 64 |

| Created formal or informal partnerships and networks across your local area for collaboration in assessing and managing family violence risk | 62 |

| Developed an organisational implementation plan | 57 |

| Updated current staff position descriptions to reflect MARAM responsibilities | 55 |

| Planned or recruited new positions to assist with organisational alignment with MARAM and increase workforce capability in line with MARAM responsibilities | 47 |

| We have not yet undertaken any activities to align to MARAM | 0 |

Summary of progress

MARAM Annual Survey results indicate that the majority of responding organisations are progressing towards MARAM alignment and that alignment remains a priority. The vast majority (80 per cent) of respondents indicate that their organisations have commenced key steps to alignment and change management activities.

At the same time, demand on the service system has generally increased. Reports of family violence steadily increased since 2017[2]. This is in part because our reforms made it easier for people to identify family violence, report it and seek help. There are more entry points for victim survivors to seek help, including through Victoria Police, The Orange Door network and Safe Steps. More professionals understand their role in identifying and responding to family violence as a result of the MARAM and Information Sharing reforms[3].

The COVID-19 pandemic may also have contributed to this increase. Family violence workers reported more first-time reports of family violence during the pandemic.

In addition, many prescribed organisations are in sectors that are experiencing broader workforce challenges that place additional demands on a limited number of staff.

This context helps to explain why workload issues and organisational funding are noted as barriers to alignment by a small percentage of survey respondents. To address this, support to operationalise MARAM is being provided through the MARAMIS Sector Capacity Building Grants program (see Chapter 8), and ongoing guidance from relevant departments. Surveyed leaders are more aware of alignment support from funded sector peaks, and support received from Safe and Equal, CFECFW and NTV has increased in comparison to the previous year.

The release of the MARAM Maturity Model (See Chapter 6) will further support prescribed organisations to self-assess and benchmark their progress throughout their MARAM alignment journey.

References

Chapter 6: Clear and consistent leadership

Embedding system-wide reform requires clear and consistent leadership. The MARAM and information sharing WoVG change management strategy sets out the following strategic actions:

- strategic plans for change management[4]

- governance to monitor and support implementation efforts

- consistent and accurate messaging

- ensuring sector readiness through implementation supports.

Section A: Family Safety Victoria as WoVG lead

Family Safety Victoria coordinates all MARAM and FVISS (MARAMIS) work across government.

Refreshed MARAMIS governance

In late 2022, Family Safety Victoria reviewed and refreshed MARAMIS governance. This responded to machinery of government changes that affected organisational structures.

The new governance structure continues to provide system-wide oversight and strategic leadership across government and the sector. It brings together expertise to address emerging needs and challenges.

Figure 7 sets out the new governance structure.

The dotted arrows reflect where groups share information, as required, on shared programs of work.

The solid arrows reflect advisory groups that directly inform other governance groups, which then ultimately reports to the Family Violence Reform Board.

MARAM Maturity Model – supporting system-wide alignment

During 2022–23, eight Sector Champion organisations, representing more than 20 services[5], guided the design of Maturity Model resources. The Maturity Model will help prescribed organisations self-assess and benchmark their progress in MARAM alignment.

Family Safety Victoria has developed the model and its resources in response to requests from organisational leaders for greater certainty and support to meet their legislative requirements. The model is also aimed at providing a common language and benchmarks for organisational alignment across all sectors and to assist in action planning.

Current resources include:

- MARAM Maturity Model on a page, which provides a snapshot of the stages of alignment

- MARAM Maturity Roadmap, which links the four framework pillars with the Maturity Model, and lists indicators and actions for each stage

- MARAM Maturity Assess Mate, an interactive self-assessment tool for organisations to get tailored suggestive action plans at a local level.

Family Safety Victoria will test and finalise the resources with department and sector stakeholders before reflecting updates and fully implementing the model in 2024–25.

Section B: Departments as portfolio leads

Department of Education

The Department of Education[6] provides leadership and oversight of MARAM implementation through the Child Safety and Family Violence Project Control Board (PCB). The PCB is responsible for major projects and the strategic direction, coordination and integration of child safety frameworks.

These frameworks include:

- Child Safe Standards

- Reportable Conduct Scheme

- information sharing and risk frameworks – CISS, FVISS and MARAM

- mandatory reporting in early childhood and care settings and schools

- criminal offences – failure to disclose offence and failure to protect offence.

The PCB also oversees DE’s responses to reports and recommendations made by external bodies. These include the Commission for Children and Young People, the Victorian Auditor-General, the Victorian Ombudsman, Family Safety Victoria, the Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor and the Child Abuse Royal Commission Interdepartmental Committee.

In 2022–23, the PCB approved approaches for:

- MARAM guidance, training development and delivery

- implementing MARAM in education and care services

- consultation about MARAM tools for education workforces

- proposed updates to the PROTECT website

- updating the Identifying and responding to all forms of harm and abuse resource and PROTECT Four Critical Actions.

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (including Family Safety Victoria)

The department works across five ministerial portfolios including Child Protection and Family Services, Disability, Housing and Multicultural Affairs, and Prevention of Family Violence.

Key activities in 2022–23 included:

- updating the Protecting Children Protocol between the department, Aboriginal Children in Aboriginal Care (ACAC) providers and Victoria Police, among other changes, including aligning to MARAM. The Protocol supports these agencies to work together to keep children safe

- piloting a new approach to collecting family violence data through the Victorian African Communities Action Plan (VACAP) Employment Brokers Program. This will help identify the number and type of family violence referrals through the program, and how family violence acts as a barrier to employment

- commencement of the disability-specific Men’s Behaviour Change (Family Violence) program for perpetrators of family violence with cognitive disability who face barriers accessing mainstream services

- information sharing resources for the community housing workforce to support the use of MARAM, the CISS and the FVISS.

Department of Government Services

Consumer Affairs Victoria transitioned from the Department of Justice and Community Safety to the newly established Department of Government Services in January 2023.

The Department of Government Services plays a leadership role in the MARAM alignment work of the Dispute Settlement Centre of Victoria (DSCV), and funded agencies in the Financial Counselling Program (FCP) and Tenancy Assistance and Advocacy Program (TAAP).

Activities in 2022–23 included:

- quarterly MARAM e-newsletters, review meetings, direct email correspondence, agency managers meetings, and practitioner network meetings. These activities support all funded programs to embed MARAM practice

- monthly meetings with DSCV, FCP and TAAP managers, and quarterly review meetings with FCP and TAAP agencies, to share feedback on progress, challenges and opportunities for improvement

- participating in WoVG working group meetings, including the MARAMIS Directors forum, CISS working group, and MARAMIS Working Group forums

- regular consultation with the Department of Justice and Community Safety MARAM implementation team about tailored family violence and MARAM training for DSCV, FCP, and TAAP delivered in the second half of 2022.

Department of Health

Throughout 2022–23, the Department of Health supported health organisations to align to the MARAM Framework.

Activities included:

- convening the MARAMIS internal working group, which assists the sector to identify and respond to family violence and helps ensure MARAM alignment successes are shared across organisations

- working on the Strengthening Hospital Responses to Family Violence (SHRFV) initiative with The Royal Women’s Hospital and Bendigo Health, which are the state-wide leads for the project

- publishing resources to support organisations such as alcohol and other drug services and Ambulance Victoria to support employees experiencing family violence.

Department of Justice and Community Safety

The Department of Justice and Community Safety’s Family Violence and Mental Health (FVMH) Branch has a MARAM team that leads implementation.

The team assists prescribed business units to provide sector support for their workforces to operationalise the MARAM Framework.

Other leadership activities in 2022–23 include:

- the Justice Health MARAM Sector Support Lead role commenced in May 2023 and began working collaboratively across the business unit and Corrections and Justice Services more broadly

- a new Community Correctional Services Family Violence Practice Committee as part of the governance structure for family violence

- new primary health service providers for Justice Health were supported to understand their contractual obligations and reporting requirements

- two Youth Justice Family Violence Practice Lead roles to support Youth Justice staff with family violence risk assessments and safety planning

- the Victims of Crime Helpline and Victims Assistance Program (VAP) continue to use the expertise of Family Violence Practice Leads (FVPLs) to provide on-the-job training, coaching and reflective practice sessions to operational staff

- Victim Services Support and Reform became the first business unit within a Victorian government department to receive Rainbow Tick accreditation, demonstrating a commitment to safe and inclusive services for the LGBTIQA+ community

- the Aboriginal Justice Group (AJG) continued to support culture and practice change in the two funded ACCOs, Djirra and Dardi Munwurro, as well as regionally based services and partners. This included ensuring services and responses provided to people from Aboriginal communities are culturally responsive and safe, recognise rights to self-determination and self-management, and consider experiences of colonisation, systemic violence and discrimination.

The courts

In 2022–23, the courts:

- commissioned an upgrade to the lizARD2 platform used by applicant and respondent practitioners. The upgrade strengthens the accurate and timely recording of MARAM assessments and improves data reporting for court users both experiencing and using family violence

- boosted the workforce to include additional roles in the Central Information Sharing Team (IST), CIP and an additional capability development officer in the MARAM team.

Victoria Police

Victoria Police prioritises MARAM alignment by driving best practice and cultural reforms.

Responding to family violence is core business for police. The Centre for Family Violence continues to deliver tailored training to achieve consistent police responses.

For Victoria Police, continual alignment with MARAM is supported through embedded roles, accountabilities, and the Family Violence Report (FVR), which operationalises MARAM for frontline members.

Dedicated Family Violence Liaison Officers embed the principles of MARAM through quality assurance of FVR reports. Divisional Family Violence Training Officers also have a key role in providing interactive education to members.

During 2022–23, Victoria Police progressed several change management activities. These included:

- boosting relationships between police and Aboriginal communities through the Police and Aboriginal Community Protocols Against Family Violence (PACPAFV). In 2022–23, the number of PACPAFV sites increased from 10 to 17

- collaborating with the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing to support the review of the Protecting Children Protocol

- developing educational resources to support training and help members understand the impacts of their response to family violence.

Victoria Police participated in many cross-government committees and advisory groups. This work supports a shared understanding of family violence risk. Through these groups, Victoria Police:

- provided strategic advice on the policing of family violence, sexual assault and child abuse

- monitored the implementation of reforms to provide feedback about the impact of police responses

- produced evidenced-based products to improve the understanding of family violence, sexual offences and child abuse.

Section C: Sectors as lead

Sector Capacity Building Grant recipients and other sector organisations continued to lead reforms within their workforces.

Some highlights during this reporting period include:

- CFECFW delivered six editions of the MARAM updates newsletter to over 560 subscribers

- VHA and NTV ran two workshops to support culture change

- VAADA delivered a quarterly MARAM newsletter for alcohol and other drug (AOD) leaders (managers and CEOs) to provide a single and regular source of truth for the sector

- VASCAL built communities of practice for the ACCO family violence sector, including Q&A panels and information sessions

- Whittlesea Community Connections (WCC) delivered a community of practice multicultural organisations with six meetings attended by 78 participants

- Safe and Equal partnered with NTV to co-facilitate a community of practice to improve understanding of newer MARAMIS concepts.

Case study: peak body collaboration

Since 2020, SASVic, in partnership with Safe and Equal and No to Violence, developed and facilitated a series of webinars to promote a shared understanding of intimate partner sexual violence (IPSV) within family violence across the three sectors.

The partnership enabled cross-sector collaboration and boosted understanding of IPSV among practitioners. This includes ensuring each sector plays a role in keeping perpetrators in view and accountable for their use of sexual violence.

In 2023, SASVic, Safe and Equal and No to Violence hosted a practitioner workshop exploring sexual violence in the context of family violence for women with disabilities. The workshop supported practitioners to develop a comprehensive understanding of how disability intersects with experiences of violence. It also deepened MARAM practice knowledge in assessing and managing risk with victim/survivors and/or perpetrators with a disability.

The workshop was run twice online in May and June. Workshops featured:

- a presentation by SASVic

- a panel discussion with managers, practice leads, and policy experts across the family violence and disability sectors

- an explanation on how a disability lens could be applied to the risk assessment tool.

The workshops also provided opportunities for promoting a shared understanding of how to apply a disability and intersectional lens when completing a risk assessment, and when managing risk. In addition, practitioners across the family violence, sexual violence and perpetrator intervention sector had the opportunity to get to know each other, enabling greater collaboration across agencies.

Summary of progress

Communicating the intent and impact of the reforms is integral to the success of MARAM. Family Safety Victoria, government departments and the sector are continuing to communicate the importance of new and upcoming resources, training and alignment activities to support the implementation of MARAM.

MARAM Annual Survey results indicate that most leaders (more than 90 per cent) reported an understanding of obligations and responsibilities under MARAM and stated that MARAM alignment is a high priority in their organisation.

References

[4] The strategic priorities of the MARAM change management strategy are outlined at Appendix 7.

[5] The eight sector champions are Bendigo Health, Bethany Community Services, Caraniche, Eastern Access Community Health, Early Childhood Australia, Safe Steps, Victorian Aboriginal Health Service and Youth Support and Advocacy Service.

[6] The Department of Education and Training was renamed The Department of Education in January 2023 following machinery of government changes.

Chapter 7: Supporting consistent and collaborative practice

Section A: Family Safety Victoria as WoVG lead

Family Safety Victoria supports consistent and collaborative practice by developing and publishing whole-of-system practice guidance and resources for all MARAM-prescribed organisations and services. This guidance can be tailored to individual workforces, as required.

MARAM practice guidance

Child and young person-focused MARAM practice guides

Family Safety Victoria is developing the Child and young person-focused MARAM practice guides and tools.

These are for direct risk and wellbeing assessment of children and young people who are victim survivors. They also support identifying and responding to young people using family violence or harm in the home and in intimate partner/dating relationships.

This new practice guidance will support workforces to respond to children and young people with a trauma and violence-informed, and age and developmental stage lens. Family Safety Victoria has partnered with a range of experts to develop and test the new practice guidance.[7]

In 2022–23, 41 consultation sessions were held with more than 500 professionals in MARAM-prescribed workforces who work with diverse cohorts.

To contribute to this work, Family Safety Victoria engaged key academics to undertake research projects. on essential questions of practice or evidence.[8]

The Child and young person-focused MARAM practice guides will be released in 2024.

MARAMIS video series project

In 2022, the MARAMIS video series project created accessible and engaging video content to highlight key concepts and practice from the MARAM practice guidance. The project was in response to sector feedback.

The videos are in two styles:

- animations exploring short, sharp specific topics

- roleplays showing longer scenes between a practitioner and client.[9]

In the 2022–23 MARAM Annual Survey, out of the 361 respondents who had viewed the resources, 79 per cent and 73 per cent respectively found the MARAM animation series and MARAM roleplay series either highly or somewhat useful.

Adolescent family violence in the home model of care

In January 2023, alongside the state-wide rollout of the Adolescent Family Violence in the Home (AFVITH) program, Family Safety Victoria implemented a new model of care within the program.

The model outlines an evidence-based, end-to-end user journey to support early intervention for young people using violence in the home and their families.

The AFVITH model of care embeds MARAM risk assessment and risk management as one of the five core components of the model.

Child and young person-focused MARAM practice guides will also support best practice in responding to young people using family violence, as well as responding to children and young people as victim survivors in their own right.

Embedding MARAM tools in online systems

At the end of June 2023, MARAM tools supporting risk assessment and safety planning were embedded in three online systems:

- Tools for Risk Assessment and Management (TRAM), which is used by practitioners in The Orange Door for risk assessment and a select number of specialist family violence and generalist agencies for risk assessment and safety planning

- The Orange Door Client Relationship Management (CRM) system, which is used by practitioners in The Orange Door for safety planning

- Specialist Homelessness Information Platform and Service Record System (SHIP), which is used by specialist family violence and homelessness services for risk assessment and safety planning.

The Adults Using Family Violence (AUFV) Comprehensive Assessment Tool supports specialist practitioners to undertake comprehensive risk assessment when working with an adult using family violence. It was released for TRAM in October 2022 and released for use in The Orange Door from July 2023.

The Predominant Aggressor Identification Tool enables professionals to accurately identify the perpetrator/predominant aggressor and respond safely to misidentification when it occurs. It was released for TRAM for agency use in April 2023. We expect to release this tool for The Orange Door, and it will be available for use in SHIP by early 2024.

Table 3: Number of MARAM risk assessments and safety plans undertaken by The Orange Door since commencement (using TRAM and the CRM)

| 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | 2022–23 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Comprehensive Risk Assessment | 4,417 | 5,879 | 9,343 | 17,945 | 24,312 | 61,896 |

| Child Risk Assessment | 942 | 958 | 2,408 | 6,050 | 9,480 | 19,838 |

| Safety Plan | 3,399 | 6,123 | 8,797 | 15,790 | 21,325 | 55,434 |

| Total | 8,758 | 12,960 | 20,548 | 39,785 | 55,117 | 137,168 |

Family Safety Victoria will continue to add MARAM tools and improve these systems for new organisations and services as appropriate. This includes the child and young-person focused MARAM wellbeing and risk tools.

Section B: Departments as portfolio leads

Department of Education

Information sharing and family violence reforms guidance and toolkit

This guidance supports the education and care workforces affected by the MARAM reforms.

It complements the training sessions and eLearning modules for centre-based education and care services, schools, system and statutory bodies; the department’s health, wellbeing and inclusion workforces; and its corporate workforces.

It is designed to be used with the legally binding CISS Ministerial Guidelines and FVISS Ministerial Guidelines.

Response to the Early identification of family violence within universal services report

During the reporting period, the department responded to the Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor’s recommendation to update guidance around school transitions.

These actions ensure that family violence risk information is consistently communicated during transition from early childhood settings to primary school, and from primary school to secondary school.

Work included:

- adding guidance on CISS and FVISS to the Transition: a positive start to school resource kit. This kit is for early childhood professionals working with children and families while they transition to school

- adding guidance on CISS and FVISS to the transition to school professional development for early childhood and Foundation teachers

- updating and inserting questions on family violence in the department’s School Entrant Health Questionnaire (SEHQ) to better align with MARAM. SEHQ is for parents to record concerns and observations about their child’s health and wellbeing as they begin primary school.

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing

Child and young person wellbeing assessment tool pilot

The Orange Door developed a state-wide child and young person wellbeing assessment tool pilot, in collaboration with The Orange Door staff, Family Services, Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare (CFECFW) and the department.

The tool is being trialled in six Orange Door sites. It will be incorporated into a risk and wellbeing assessment for children and young people.

CFECFW has been funded for two years to boost capability in assessing child and young person wellbeing. This includes on-site support, the development of practice guides and webinars.

CIP expansion

In November 2022, the department expanded CIP to Safe Steps and Men's Referral Service as a phased rollout in line with the Royal Commission's recommendation.

This supports the intake and high-risk service responses of the family violence system.

Revised Homelessness and housing support guidelines

The revised guidelines replace the 2014 Homelessness services guidelines and conditions of funding. They build on the COVID-19 amendment to the guidance published in 2021.

They guidelines promote consistent application of the MARAM Framework by:

- reinforcing the obligation of government-funded homelessness organisations to comply with the Family Violence Protection Act 2008

- outlining the pillars and principles that underpin the MARAM Framework and intersections with the CISS and FVISS

- assisting homelessness organisational leaders to understand which of the 10 MARAM practice responsibilities apply to their organisation

- highlighting the responsibilities for risk assessment and management held by homelessness organisations

- providing references to sector-specific resources, practice guides, templates, tools, and training to promote workforce access to learning opportunities.

The inclusion of this comprehensive overview of MARAM in the updated guidelines will promote consistent application of the framework across the state-funded homelessness service system. The guidelines are currently under review and will be published in late 2023.

Easy English and multilingual fact sheets

The department released easy English and multilingual factsheets in 2022–23.

The factsheets outline the MARAMIS reforms to support people from multicultural communities accessing the department’s services. They were tested through an external consumer testing workshop to ensure they were fit for purpose.

The fact sheets are translated into six commonly used languages including Dinka, Somali, Simplified Chinese, Oromo, Arabic, Vietnamese, as well as easy English.

Department of Government Services

In 2022–23, the Department of Government Services (DGS) continued to embed MARAM in ongoing practice. This included:

- working with funded agencies to map co-location of Financial Counselling Program (FCP) and Tenancy Assistance and Advocacy Program (TAAP) in The Orange Door network to improve information sharing and holistic support for victim survivors

- secondary consultations between staff from DGS agencies and specialist family violence services

- providing community education to services including mental health services, Aboriginal community-controlled organisations (ACCOs), the Salvation Army and homelessness services

- working closely with DSCV to develop risk-screening procedures and a risk identification tool

- collaborating with Tenants Victoria to establish a TAAP community of practice

- developing tools including:

- the MARAM screening and identification flow chart

- a safety plan template for non-specialist workforces

- Family violence information sharing practice toolkit to build on the training and address gaps in practice knowledge.

Department of Health

In 2022–23, the Department of Health continued to support MARAM practice across all health workforces. This included:

- dedicated project funding for 26 public hospitals and health services to implement the SHRFV initiative and provide mentoring and support to other public health services across Victoria in a hub and spoke model

- funding for The Royal Women’s Hospital and Bendigo Health – the State-wide Lead (Metropolitan Sector) and State-wide Lead (Regional Sector) respectively – to embed MARAM and MARAMIS in whole-of-hospital responses to family violence

- securing funding under the National Partnership Agreement on Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence Responses 2021–23. This funding enabled The Royal Women’s Hospital, in collaboration with the University of Melbourne, to undertake three projects to support health services to identify and respond to family violence. These include:

- developing sustainable antenatal family violence screening for women who do not speak English

- evaluating the SHRFV program

- implementing and evaluating family violence clinical champions (who support staff responding to family violence) and contact officers (who support staff experiencing family violence) across six health services

- developing guidance for health organisations about seeking secondary consultations in relation to family violence. The guidance was recommended by the Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor in its May 2022 report on the early identification of family violence within universal services.

Department of Justice and Community Safety

During the reporting period, the Department of Justice and Community Safety continued to implement and embed MARAM practice throughout its workforces. This included:

- the Family Violence Restorative Justice service continuing to use TRAM

- the Victims of Crime Helpline developing bespoke MARAM-aligned risk assessment tools and training for use with male victims of family violence. This includes predominant aggressor tools

- reviewing the Community Correctional Services (CCS) practice guidelines to further incorporate MARAM concepts and strengthen case management practice

- a mapping exercise of the journey for people subject to CCS supervision and those in custody to understand how and when MARAM will be implemented and integrated into the corrections system

- a mapping exercise to map central business units, CCS and prison workforces against the 10 MARAM responsibilities

- funding for Caraniche Forensic Youth Service to conduct comprehensive clinical and forensic risk assessments to identify risk factors and treatment needs of young people

- producing an FAQ document that provides Youth Justice staff with guidance on the proper use of the L17 Portal

- MARAM victim survivor screening for young people upon Youth Justice intake. If the screen indicates that family violence is present, a full MARAM assessment is completed.

The courts

The courts undertook a range of MARAM-related activities in 2022–23, including:

- expanding the Remote Hearing Support Service to 11 courts across Victoria. This provides increased accessibility and safety for victim survivors

- trialling a Central Family Violence Practitioner team at the Magistrates’ Court

- establishing the Koori Family Violence Online Support Service to support Koori men and women using or experiencing family violence.

Victoria Police

Consistent and collaborative practice is supported through a range of improvement activities. MARAM related activities completed in 2022–23 include:

- collaborating with the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing through the Vulnerable Children’s Committee to improve processes related to DFFH intakes

- updating the Code of Practice for the Investigation of Family Violence. The Code of Practice is an external document for the community to find out about the roles and responsibilities of Victoria Police, and how police respond to reports of family violence

- working with key partners to roll out a trial to identify improvements to Victoria Police policy and practice, to reduce the impact of misidentification of predominant aggressor

- developing clear and intuitive information sharing processes and guidance in consultation with agencies prescribed through MARAM

- improving data collection processes to enable a holistic understanding around engagement practices for Family Violence Training Officers, who maintain strong collaborative relationships with frontline members and external stakeholders within their regions, particularly with The Orange Door.

The Code of Practice is an external document for the community to find out about the roles and responsibilities of Victoria Police, and how police respond to reports of family violence.

Information sharing

Information sharing is an indicator of consistent and collaborative practice. This section outlines information sharing demand and activity for departments that centrally collected FVISS and CISS data in the 2022–23 reporting period.

Available data suggests information sharing is increasing over time. It shows:

- there is an increase in family violence being identified

- practitioners are gaining confidence in multiagency collaboration

- MARAM and related information sharing reforms are progressing and maturing

- the impact of prescribing additional workforces in April 2021, and the continued training and capability building activities that have occurred over 2022–23.

It should be noted that there is no legal requirement to collect FVISS and CISS data. Data that is available is from departments with the ability to collect central information. For those that do, this section outlines information-sharing demand and activity in the 2022–23 reporting period.

Table 4: 2022–23 information sharing requests received by department.

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFFH Child Protection | 1,309 | 1,181 | 1,327 | 1,539 | 5,356 |

| DJCS Corrections Victoria | 2,475 | 2,960 | 3,987 | 4,761 | 14,183 |

| The courts | 11.249 | 11,791 | 13,431 | 13,073 | 49,544 |

| Victoria Police | 1,905 | 1,808 | 2,020 | 1,518 | 7,251 |

| Total[10] | 16,938 | 17,740 | 20,765 | 20,891 | 76,334 |

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing – Child Protection

The Department of Families, Fairness and Housing’s Information Sharing Team (IST) receives information sharing requests under the FVISS and CISS. The team completes responses on closed child protection cases. Consolidated data in Table 4 shows the number of information sharing requests received by Child Protection in 2022–23.

Victoria Police, specialist family violence services and hospitals made the most frequent requests for information sharing about family violence in 2022–23. This continues the trend from 2021–22.

Overall:

- IST received 47 per cent more FVISS and CISS requests compared with 2021–22

- requests increased throughout the year, with Q4 2022–23 receiving 78 per cent more FVISS and 67 per cent more CISS requests than in Q1

- other (non-CISS or FVISS) requests rapidly declined by 82 per cent from Q1 to Q4 2022–23. This followed the launch of a new case management system that streamlined processes and improved data accuracy (discussed in the ‘Continuous improvement’ section).

Requests declined and proactive shares

A total of 260 information sharing requests were declined in the 2022–23 financial year. This was because they did not meet FVISS or CISS thresholds, or the request did not have enough detail to be assessed.

If a request does not have enough information, the IST liaises with the requestor to obtain additional information. If a request cannot be responded to under FVISS or CISS, appropriate referrals are considered, for example to the Freedom of Information team or another ISE.

In 2022–23, the IST proactively shared relevant information on 115 occasions.

The data shows that the team has proactively shared information on more individuals under CISS than FVISS. This is potentially due to the broader nature of the CISS thresholds (that is, child protection clients are all children) compared with FVISS thresholds.

Continuous improvement

In October 2022, the IST transitioned to a new case management system. This streamlined previously manual administrative processes, improved data accuracy and reporting, and mitigated risk in relation to the processing and storing of sensitive client information.

The new system also standardises ISEs’ requests for child protection information and migrates historical records.

The new case management system helped to reduce the number of non-compliant FVISS and CISS requests, demonstrated by the rapid decline in ‘Other’ requests in Table 4.

The IST also commenced a project in February 2023 to strengthen information sharing practices within the department and promote further alignment with MARAM.

The project supports the use of FVISS and CISS in conjunction with other information sharing pathways. It promotes better understanding of information sharing responsibilities and provides practical supports, resources and other tools for staff.

Department of Justice and Community Safety

Corrections and Justice Services respond to FVISS requests via two teams:

- the FVISS team in Corrections Victoria (CV), which responds to CV and CCS relevant requests

- Justice Health, which responds to health information requests for people in custody.

During 2022–23, FVISS requests in CV and CCS significantly increased. In 2022–23, there was a 129 per cent increase, with 745 requests in July 2022 increasing to 1,705 requests in June 2023.

This may be due to: organisations maturing in their FVISS implementation and operation; expansion of The Orange Doors and RAMPs; uncertainty in other legislative schemes; and The Orange Door requesting information directly from CV, mitigating delays from requests made through the CIP.

Consolidated data in Table 4 shows the number of information sharing requests received by CV and CCS under FVISS for the 2022–23 financial year.

Requests declined and proactive shares

CCS continues to reinforce proactive sharing of risk relevant information with external service providers. CCS encourages staff to gather relevant information using the scheme, for example L17 narratives to better understand family violence risk towards victim survivors.

CCS also regularly discusses privacy issues with staff to ensure they consider the limitations in relation to information sharing.

Continuous improvement

Victim Services Support and Reform (VSSR) is improving information sharing approaches and strengthening referral pathways with key stakeholders and partner agencies.

VSSR and Family Safety Victoria have developed interim guidance to support the interface between The Orange Door sites and VSSR.

VSSR has also established a memorandum of understanding with Thorne Harbour Health to strengthen referral pathways for male victim survivors of family violence.

The Victims of Crime Helpline is the main referral pathway for Victoria Police referrals (L17s) for adult males (17 years and over) identified as victims of family violence during a family violence incident.

The Helpline also plays a central role in identifying and assessing predominant aggressors. Reassessing misidentified victim survivors occurs mainly through the FVISS and CISS.

The FVISS and CISS enables the Helpline to share information to correctly identify the victim survivor and perpetrator.

The courts

The number of FVISS and CISS requests received by the courts increased in 2022–23. The courts received 49,544 FVISS/CISS requests in 2022–23, an increase of more than 44 per cent since 2021–22. 49,396 requests were under FVISS (99.7 per cent), and 148 requests were under CISS (0.3 per cent). This included 25,305 (55 per cent) requests from The Orange Door network and 13,341 (44 per cent) requests from Child Protection.

The remaining 22 per cent of FVISS requests came from specialist family violence service providers including Safe Steps and community-based organisations.

This increase reflects the essential role the courts play in information sharing, as well as the value of the information courts hold for the purpose of risk assessment and management.

Continuous improvement

In response to this increase in demand, the courts commenced a project to develop a portal to automate functions for ISEs and court staff. This project will help the courts provide a timely response to requests for information by:

- allowing ISEs to lodge and track applications through a web-based portal

- allowing for direct communication with Central Information Sharing Team from within the portal

- automatically generating data on the volume and nature of requests for reporting purposes.

The courts also commenced in-depth consultations with partner agencies that support Drug Court participants. This process will determine best practice for risk assessment, information sharing and management responsibilities.

Victoria Police

Victoria Police continues to lead under FVISS/CISS by developing clear and intuitive information sharing processes and sharing guidance with other agencies to encourage consistency across the service system.

Continuous improvement

To improve capability and ensure requests from ISEs have enough information to meet Victoria Police’s thresholds for sharing under the FVISS/CISS, the organisation presented training sessions for social work professionals, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander services, psychologists, alcohol and drug counsellors and child protection professionals.

To complement this training, Victoria Police is also developing an instructional video for ISEs on how to submit a valid request under FVISS/CISS. This video will be circulated to The Orange Door and other ISEs to strengthen their requests to Victoria Police.

The increase in voluntary sharing in this reporting period is possibly due to a pilot program being run through the Proactive Policing Unit (PPU).

Section C: Sectors as lead

- The MARAM Sector Grants Multicultural Consortium of Whittlesea Community Connections (WCC), AMES Australia and Jewish Care Victoria established a community of practice for bilingual practitioners in the multicultural community and settlement sectors. Members reported increased knowledge about the MARAM Framework and Information Sharing Schemes and better collaboration. They viewed the group as a safe platform for reflective practice and debriefing.

- Council to Homeless Persons (CHP) uses the Basecamp tool to facilitate collaboration between MARAM Sector Capacity Building Grants recipients. This tool has improved communication, allowing recipients to discuss lessons learned, promote and strengthen collaboration, and share resources. CHP plans to further explore its functionality, using it for ongoing discussions, deadline coordination and individual working groups.

- NTV’s Family Safety Advocate (FSA) community of practice delivered nine sessions in 2022–23, with an average of 10 attendees. These sessions built confidence in MARAM practice concepts and alignment.

- VHA collaborated with the CFECFW and VAADA to facilitate a MARAMIS webinar and information session to members of all three peak bodies, with 126 practitioners in attendance.

Case study: alcohol and drug service

Sarah* was an AOD practitioner providing AOD counselling to Joshua* to explore his substance use. After about two weeks, she became concerned Joshua was using family violence.

Joshua had talked about calling his partner, Hayley*, names, yelling at her and putting her down. He disclosed constantly looking through her phone, following her car and blaming Hayley for his behaviour.

Sarah was experienced in working with victim survivors of family violence, and familiar with the MARAM guidance and tools for adults using violence, but she needed some support to understand her observations.

Sarah sought a secondary consultation with her agency’s Specialist Family Violence Advisor (SFVA).

The SFVA supported her to use the MARAM adults using violence assessment tool to better understand Joshua’s violence and the risk to Hayley.

The SFVA also gave Sarah advice on ways to continue exploring Joshua’s use of family violence and substance use in their counselling sessions.

This helped Sarah to talk to Joshua about his behaviour in a non-confrontational, respectful, and cautious manner.

Sarah continued seeking advice from the SFVA about the level of risk and whether she needed to share information, and how to develop a MARAM safety plan for people using violence with Joshua.

The safety plan included protective factors, risk factors, and who Joshua could call for support.

Sarah was able to maintain a professional relationship with Joshua, keep him in view and hold him to account as a person using violence.

She was also able to keep Hayley’s safety in view by regularly reviewing the safety plan with Joshua and keeping in touch with the SFVA.

*case study is a fictitious example of MARAM safety planning in AOD work

Summary of progress

Embedding consistent and collaborative practice is crucial to supporting victim survivors’ safety and keeping perpetrators in view.

All departments have embedded practice by developing additional resources to support workforces to consistently assess and manage family violence risk, and to collaborate effectively.

The Five-year legislative review of MARAM, FVISS and the CIP showed that MARAM and the associated information sharing reforms have been effective in driving cultural change.

This includes supporting practitioner confidence to share information, and a positive cultural shift away from maintaining perpetrator privacy towards sharing information to keep victim survivors safe and holding perpetrators accountable.

By increasing services’ access to relevant information under MARAM, practitioners are making more informed decisions about family violence risk.

Throughout the reporting period, departments reported significant growth in information sharing requests and, to a lesser extent, proactive information sharing.

This shows that collaboration between sectors is continuing to grow alongside embedding of MARAM practice and the information sharing schemes.

References and footnotes

[7] Partners include Monash University, RMIT University, Safe and Equal, The Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare, Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA), Yoowinna Wurnalung Aboriginal Healing Service and Youth Support and Advocacy Service (YSAS).

[8] This includes: RMIT’s Adolescents using family violence (AFV) MARAM practice guidance project 2022: review of the evidence base; Monash University’s I believe you report and Young people’s experiences of identity abuse in the context of family violence: A Victorian study; and Swinburne University and Safe and Equal, who will design identification and assessment tools that will be incorporated into the final Child and young person-focused MARAM practice guides and tools.

[9] VAADA, NTV, Safe and Equal and Elizabeth Morgan House supported the development of the roleplay videos.