- Published by:

- Family Safety Victoria

- Date:

- 3 June 2021

This report details the 2019-20 workforce census findings for the primary prevention workforce.

Introduction

Royal Commission into Family Violence, research objectives, target groups and primary prevention workforce definition.

Background

In March 2016, the Royal Commission into Family Violence (RCFV) delivered a multi-volume report with 227 recommendations directed at improving the foundations of the system, seizing opportunities to transform the way that the Victorian Government responds to family violence, and building the structures that will guide and oversee a long-term reform program that deals with all aspects of family violence.

The recommendations of the RCFV highlighted the lack of detailed knowledge and systematic collection of data about family violence and related workforces in Victoria, which has made effective industry and workforce planning challenging. The RCFV recommendations also confirmed the important role that these workforces play in identifying and addressing family violence.

In response to these findings, a commitment was made to undertake a family violence workforce census (the Census) every two years in a continued effort to address this gap. The first Census was conducted in 2017, and in July 2019, Family Safety Victoria (FSV) commissioned ORIMA Research to design and deliver the 2019-20 Census.

Research Objectives

The overarching aim of the 2019-20 Census was to assist in deepening the Victorian Government’s understanding of a range of issues in the context of reforms recommended by the RCFV.

More specifically, the Census aimed to:

- provide an evidence base for the analysis required to inform the Victorian Government’s decisions relating to industry planning and associated workforce reforms; and

- enable a more nuanced understanding of specialist family violence and primary prevention workforces through targeted consultation, surveying and regional analyses of these workforces.

The findings of this Census will help the Victorian Government to better understand the breadth and nature of workforces that come into contact with family violence; identify opportunities to build on knowledge, support and capability; as well as build on what is known in order to maintain its commitment to keep improving family violence prevention and response in Victoria.

Three target groups (workforces) were identified for the Census, as detailed in Table 1. This report presents the 2019-20 Census findings for the second target group listed – those who completed the Census in a primary prevention capacity1.

Target groups and workforce definition

Project development

Footnotes

- Where respondents indicated that they held paid roles across multiple workforces, the initial screening questions directed them to complete the Census in the capacity of only one of these workforces. To request the full questionnaire please email the Centre for Workforce Excellence at cwe@familysafety.vic.gov.au

- Preventing Family Violence and Violence Against Women Capability Framework(opens in a new window)

Executive Summary

Summary or workforce census results for the primary prevention workforce.

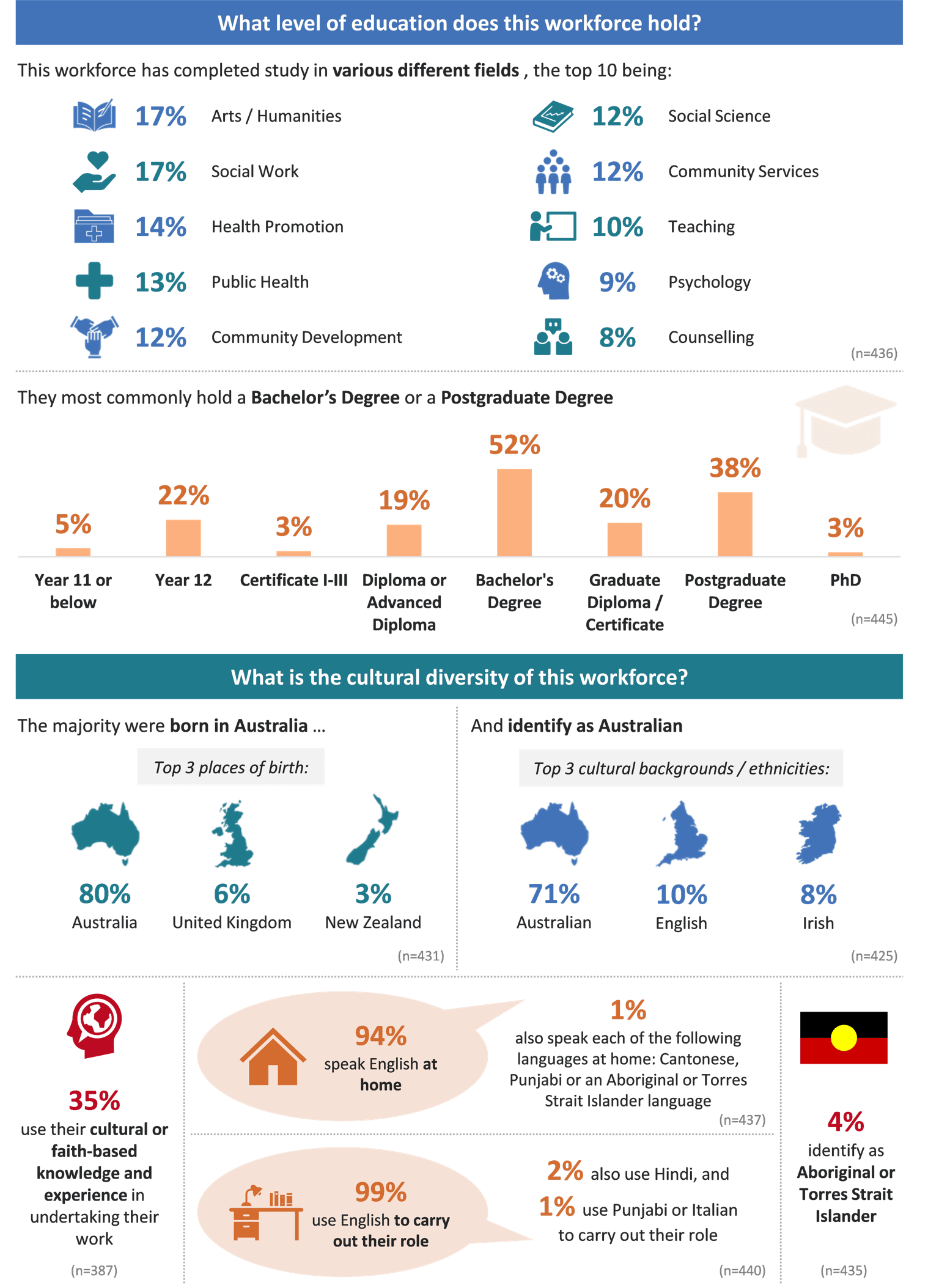

Role requirements

The Census results identified the diversity of activities undertaken by the primary prevention workforce, and the varying frequencies at which these activities are conducted. The core activities most frequently undertaken by this workforce included developing and maintaining partnerships and networks, project management, and planning / implementing primary prevention initiatives.

Employment conditions

Both the Census results and findings from the initial sector consultation suggested that workers in the primary prevention workforce were less likely than the average Victorian to hold a full-time role. However, almost one-fifth of the workforce reported that they held at least one additional paid role outside of the primary prevention workforce, and one-in-ten held more than one paid role within this workforce. Additionally, many employees reported that they were employed on fixed-term contracts, and many also reported working additional unpaid hours.

Supervision

The results indicated that the primary prevention workforce was broadly satisfied with the quality of support provided by their supervisor or direct manager, and that having the opportunity to regularly discuss their professional development, or their work more generally, were key drivers of this satisfaction.

Training and confidence

While the primary prevention workforce had completed training across a range of topic areas, overall confidence in their level of training and experience was moderate. The findings highlighted MARAM as a priority area for further / improved training and professional development.

Health and wellbeing

Overall, the results of both the Census and the initial consultation phase of the project suggested that many within this workforce experience stress due to high workload. Despite this, few were dissatisfied in their current role and most felt that they made a difference to people affected by family violence.

Career and future intentions

The results showed that people shared a number of positive reasons for working in the primary prevention workforce, including a strong commitment to preventing / responding to family violence and gender equity.

Regarding future intentions, almost half of all primary prevention practitioners reported that they had plans to leave their current role. Although many planned to do so due to an end of contract, others were influenced by better career prospects.

Profile of respondents

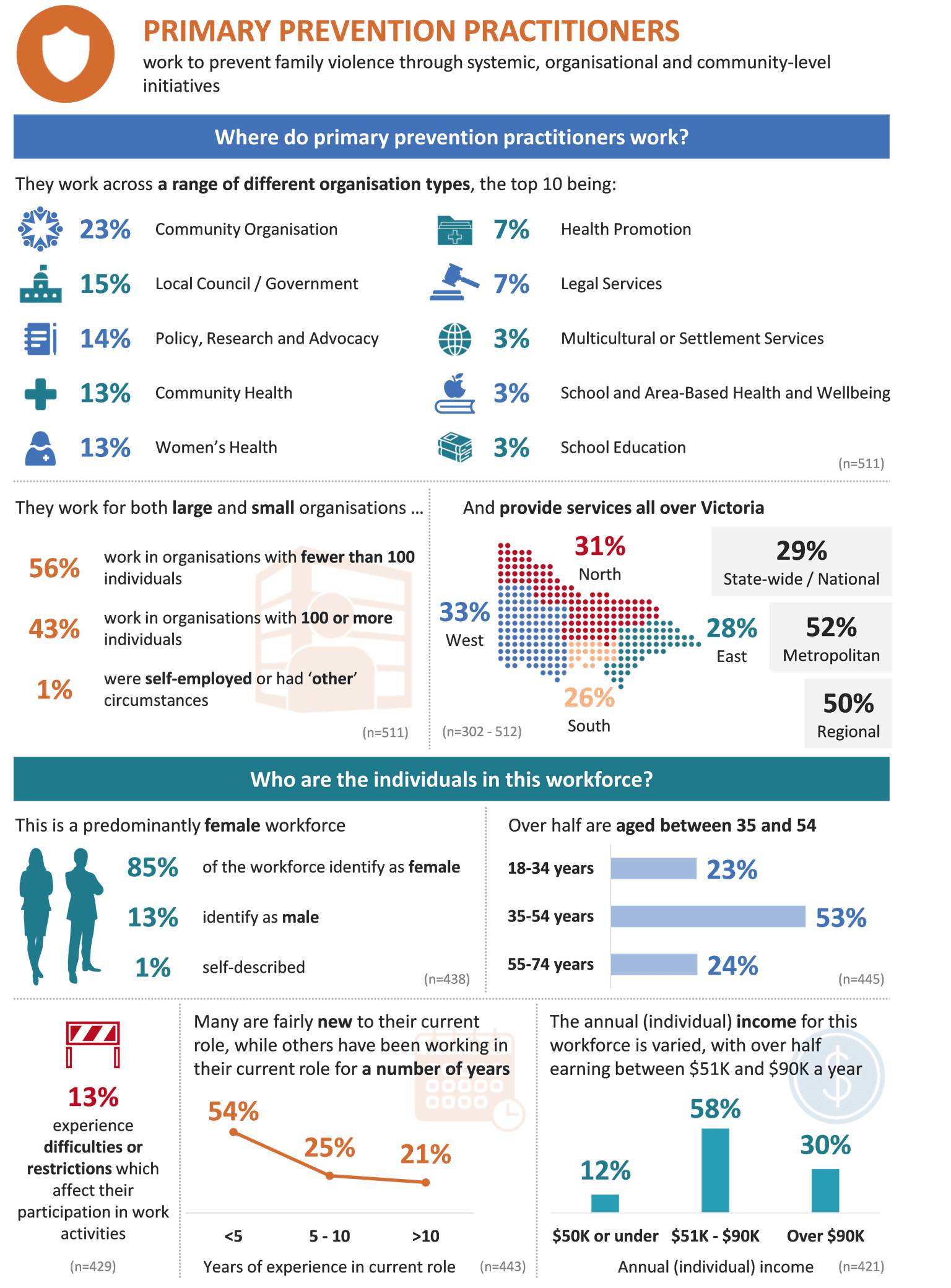

Primary prevention practitioners prevent family violence through systemic organisational and community-level initiatives.

Role requirements

Primary prevention practitioners are responsible for designing and implementing projects and programs that aim to prevent or reduce the incidence of family violence.

They utilise a variety of approaches in their work, including awareness raising, partnership development, community development, advocacy, and structural, environmental, organisational and systems development.

The primary prevention practitioner workforce comprises a range of roles. This chapter summarises the role requirements of this workforce both generally and as they relate to family violence.

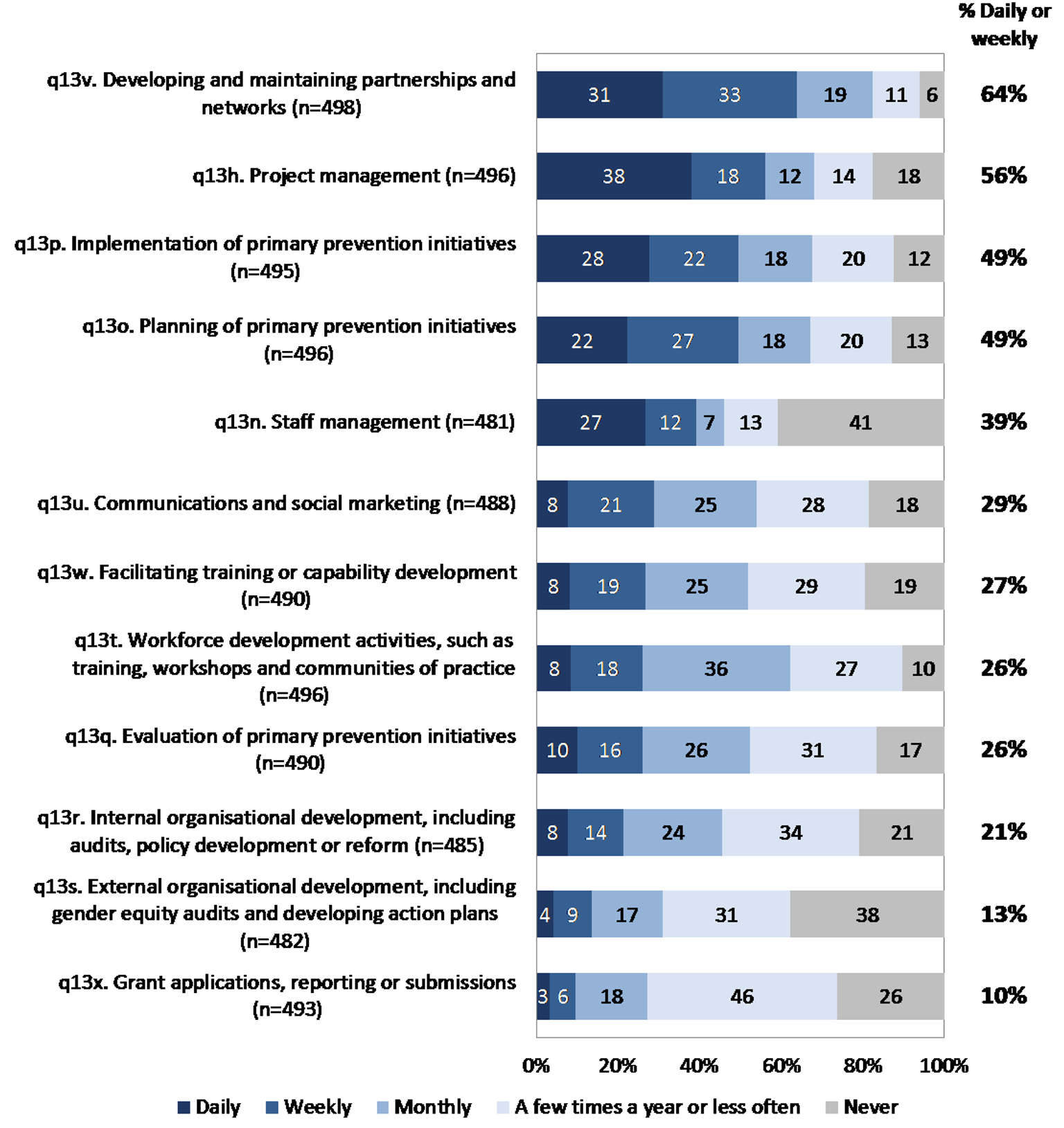

Overall, the Census results identified the diversity of activities undertaken by this workforce, and the varying frequencies at which these activities are conducted. As perhaps expected, respondents were more likely to report that they frequently worked on activities that were core to their primary prevention role (such as partnership development and primary prevention initiatives), and undertook family violence response-specific activities less frequently (particularly those related to information requests and client referrals).

Employment conditions

This chapter details the employment conditions of the primary prevention workforce.

This includes the nature of contracts held (full-time, part-time, casual or other; ongoing versus fixed term), average number of hours and days worked, and amount of unpaid work undertaken.

Exploring these conditions can assist in our understanding of any challenges they may face in undertaking their work, and aid in the interpretation of subsequent results throughout this report.

Overall, both the Census results and findings from the initial sector consultation suggested that workers in the primary prevention workforce were less likely than that of the average Victorian to hold a full-time role. Additionally, many employees reported that they were employed on fixed-term contracts, and many also reported working additional unpaid hours.

The Census results indicated that the roles held within the primary prevention workforce were highly varied in terms of working hours and contract conditions (i.e. ongoing versus fixed-term).

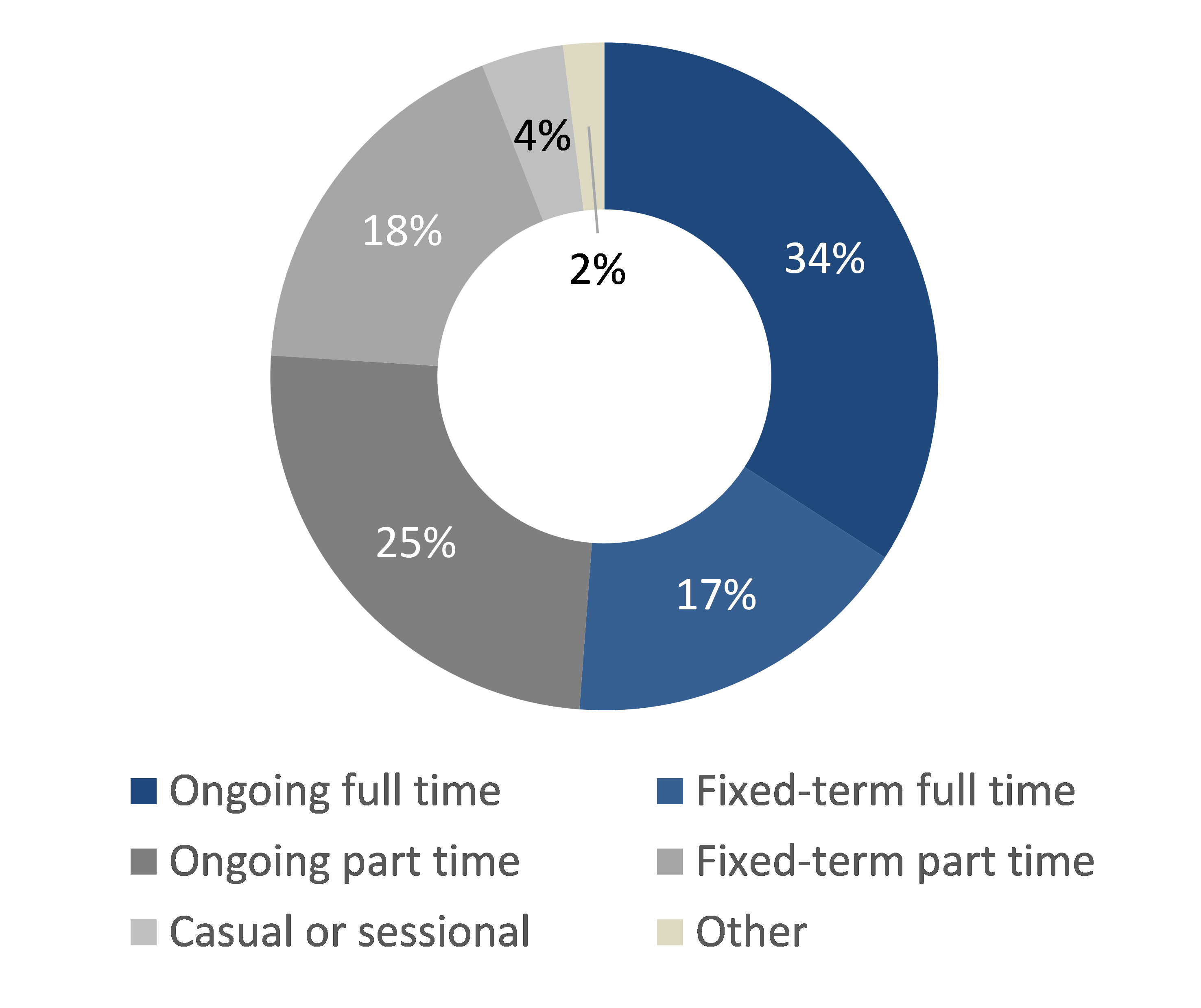

Figure 3 illustrates that just over half of the primary prevention workforce reported that they were employed on a full-time basis (51%) — lower than the average proportion across Victoria as a whole (67%1). Of the remaining 49%, the majority were employed on a part-time basis (43%), and very few were casual or sessional employees (4%).

Furthermore, although 59% were employed in an ongoing capacity, about 35% held fixed-term roles.

While those in the primary prevention workforce were less likely than the average Victorian to hold a full-time role, it should be noted that overall, almost one-fifth of this workforce reported that they held at least one additional paid role outside of the primary prevention workforce (17%), and one-in-ten held more than one paid role within this workforce (10%).

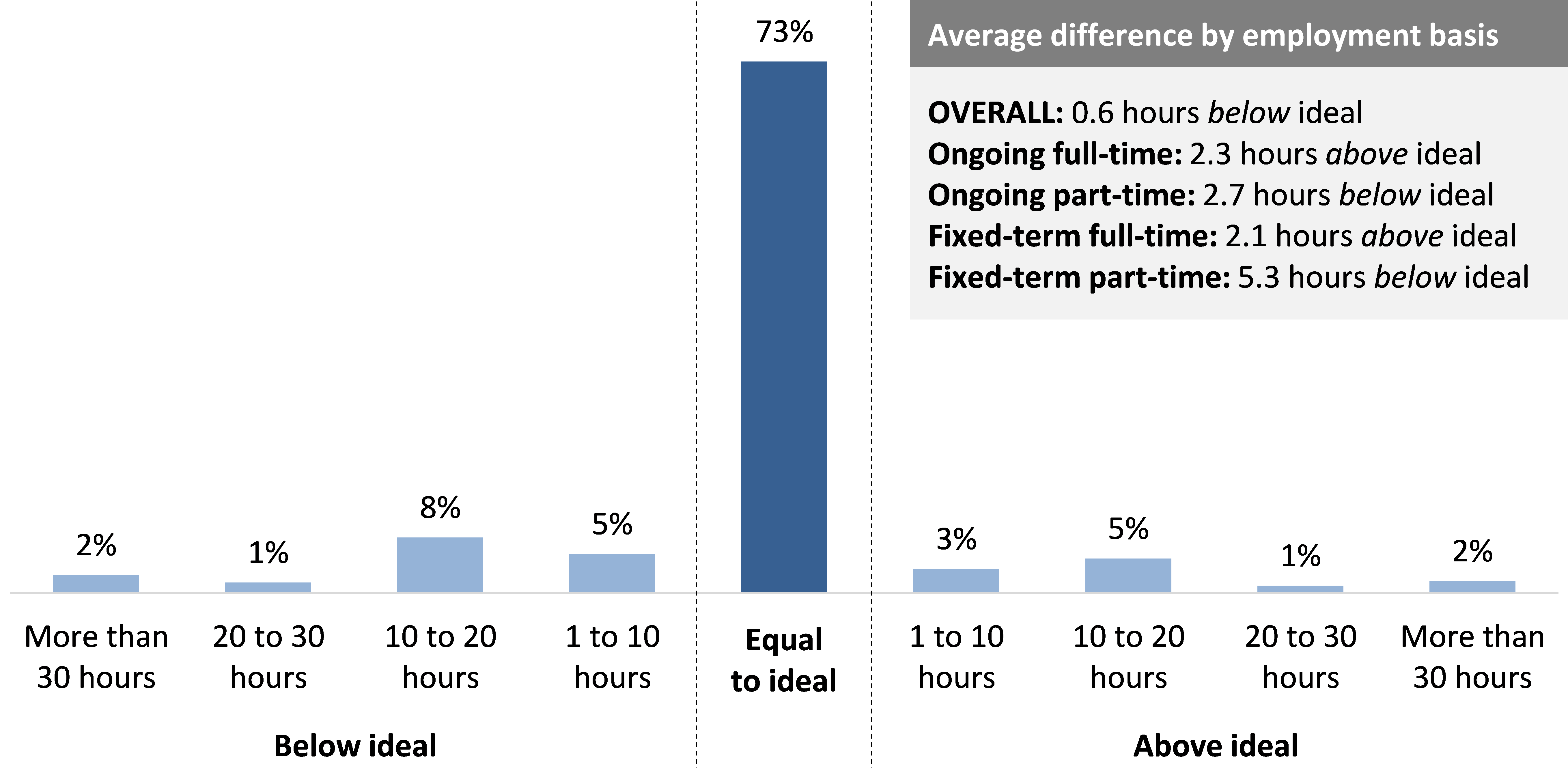

As shown in Figure 4 overleaf, the majority of the workforce (73%) reported that in the past fortnight, the number of hours they were employed to work was equivalent to the number of hours they ideally wanted to be employed to work in this role. The difference between actual and ideal hours worked naturally varied by basis of employment, with part-time employees generally more likely than full-time employees to report a desire to have been employed for a greater number of hours in the last fortnight.

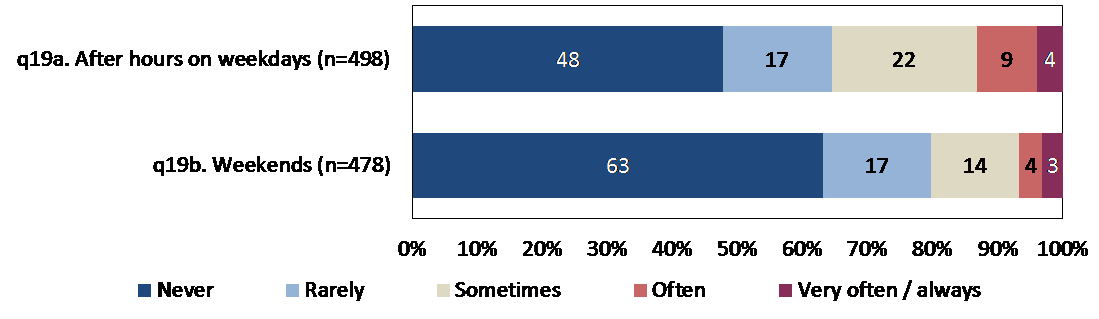

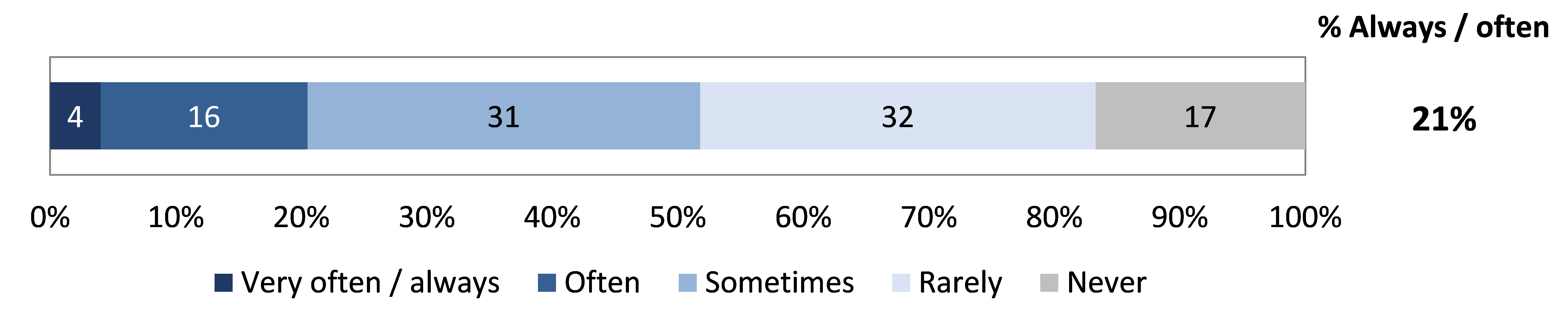

Only a relatively small proportion of the primary prevention workforce were employed to undertake their work outside of business hours often or very often / always (7%-13% – see Figure 5), suggesting that only a minority undertake regular shift / evening work, or weekend work.

Although the majority were paid to undertake their work during normal business hours, one-third of the workforce reported that they often work additional unpaid hours (21% often and 13% very often / always), whilst a further 30% noted that they sometimes do so.

Footnotes

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 6202.0 – Labour Force, Australia, Mar 2020.

Supervision

This chapter explores the extent to which the primary prevention workforce felt supported in the workplace, and the nature of their interactions with supervisors or managers.

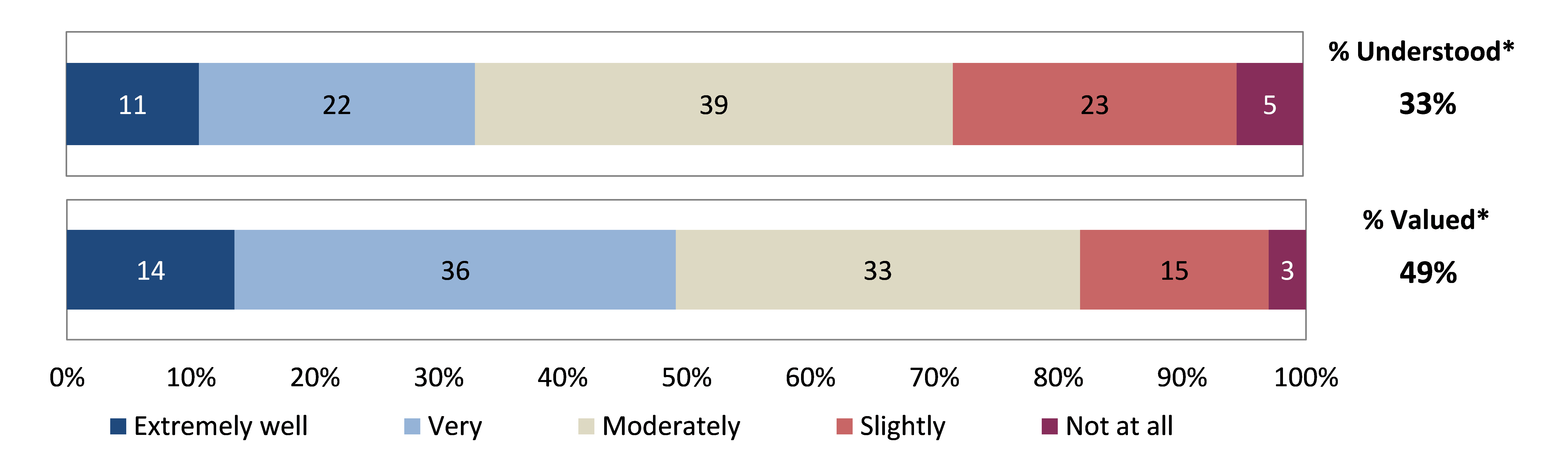

Overall, the results indicated that the primary prevention workforce were satisfied with the quality of support provided to them by their supervisor or direct manager, and that having the opportunity to regularly discuss their professional development, or their work more generally, were key drivers of this satisfaction. Subsequent findings suggested that at least half of the workforce did not feel that their role was well understood or valued by others in their organisation, suggesting that some of this workforce may feel under-recognised by their peers.

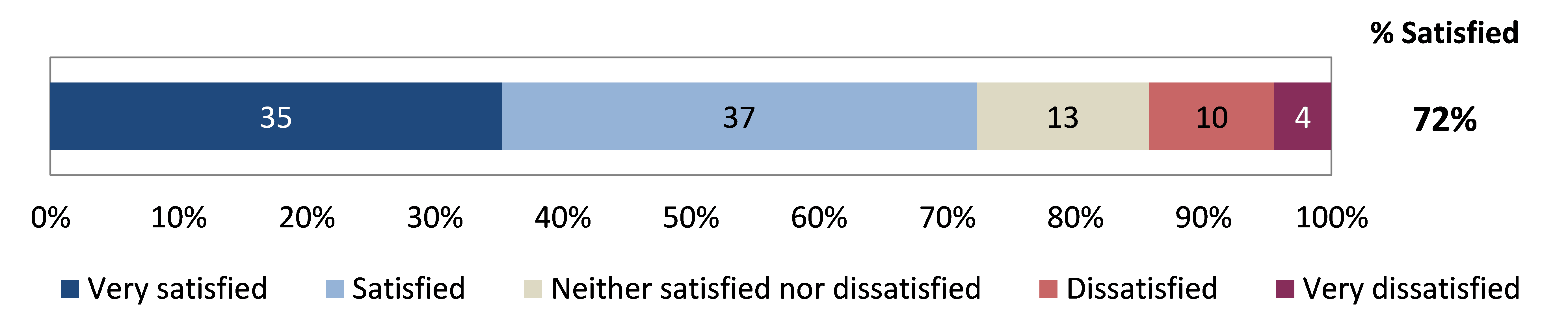

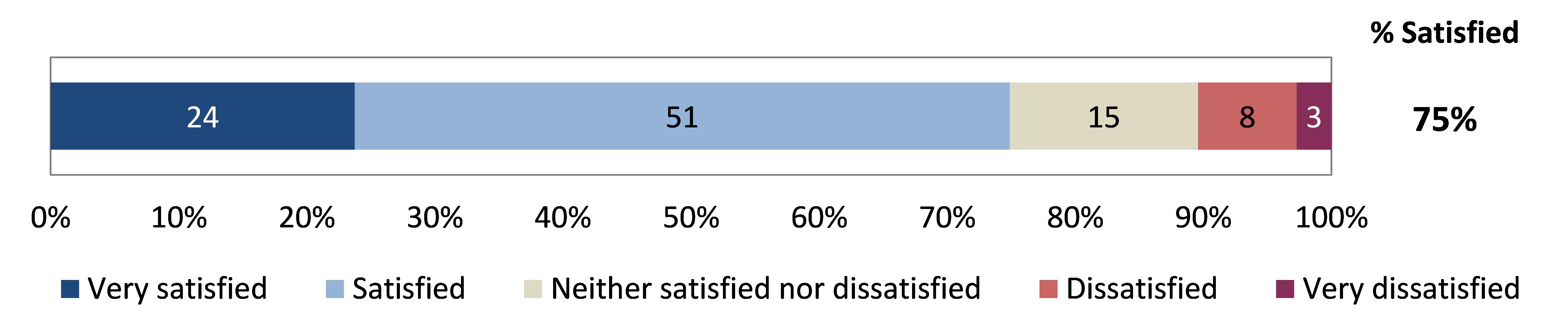

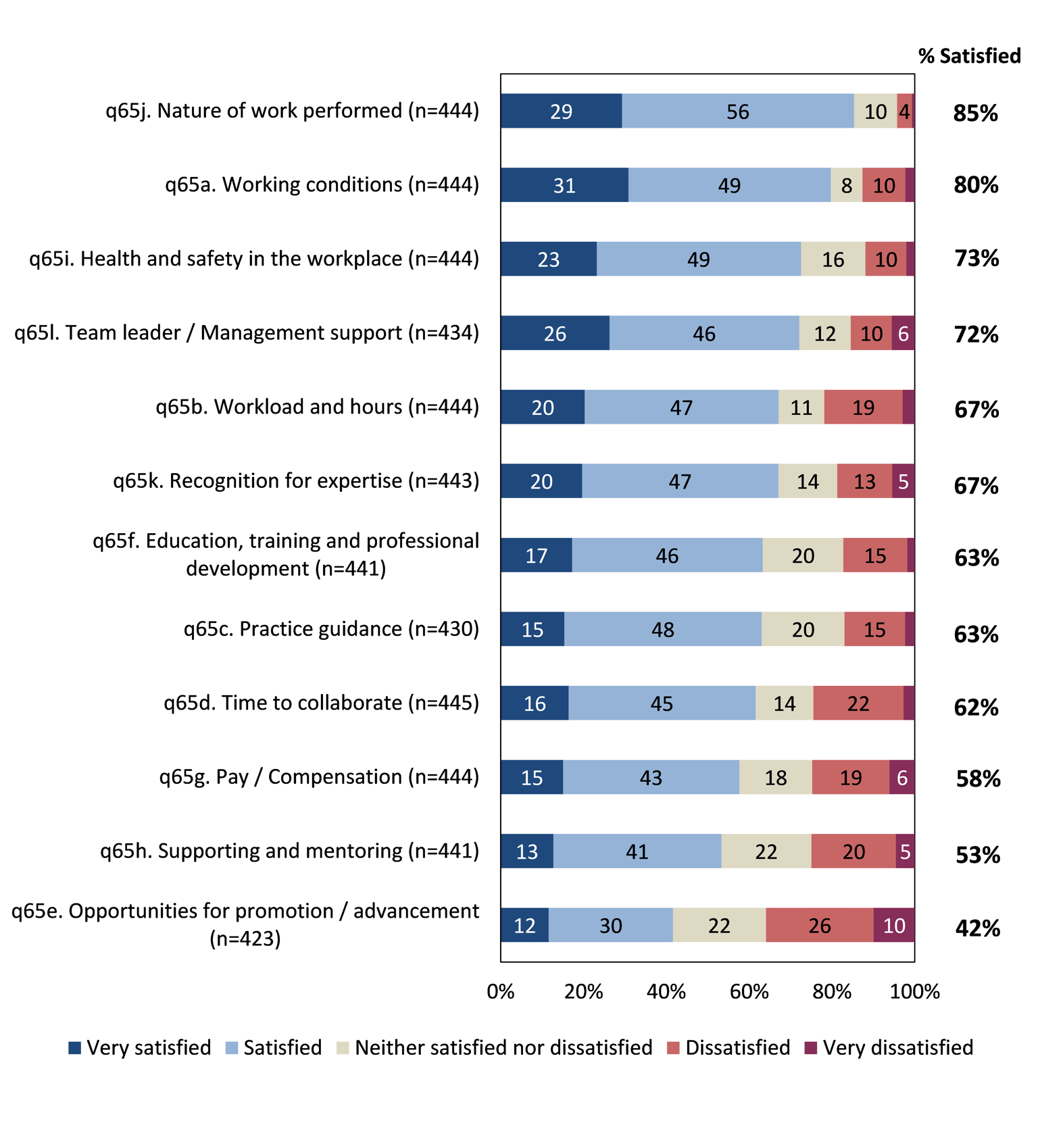

Overall, the primary prevention workforce was largely happy with the quality of support provided to them by their supervisor or direct manager, with over seven-in-ten reportedly satisfied (72% – see Figure 6).

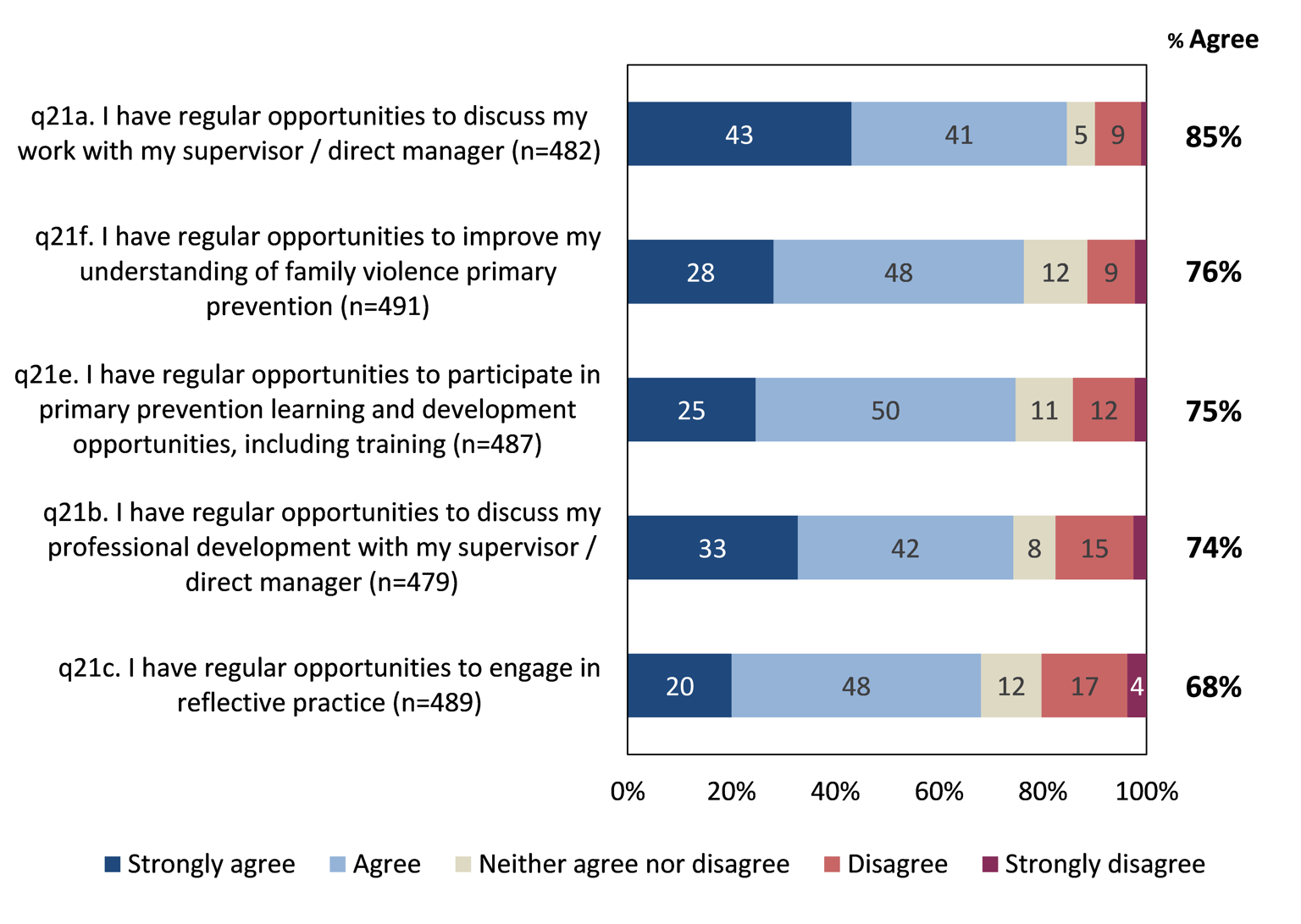

When asked about a range of more specific metrics associated with the support that their supervisors / managers had provided, 85% agreed that they had regular opportunities to discuss their work with their supervisor or direct manager. Furthermore, around three-quarters of the workforce also agreed that they have regular opportunities to improve their understanding of family violence primary prevention or upskill through participation in training or discussions regarding their personal development (74%-76%).

Although 68% agreed, the workforce was relatively less likely to feel that they have regular opportunities to engage in reflective practice1, with 20% disagreeing that they had such opportunities.

In order to determine what is most important in influencing the overall levels of satisfaction with support provided by supervisors / managers amongst this workforce, regression analysis was undertaken. The results suggest that the key drivers were having regular opportunities to:

- discuss professional development

- discuss work more generally

- participate in primary prevention learning and development opportunities, including training.

Footnotes

- Reflective practice, also referred to as critical reflection or reflexivity, is a process of self-examination by a practitioner about their own work; becoming self-aware, considering their thoughts, feelings and assumptions, and examining how these impact upon their work.

Training and confidence

This chapter discusses the extent to which primary prevention workforce respondents were confident in their role, as well as any training or professional development they had undertaken in a range of skill and capability areas, generally and as they relate to family violence.

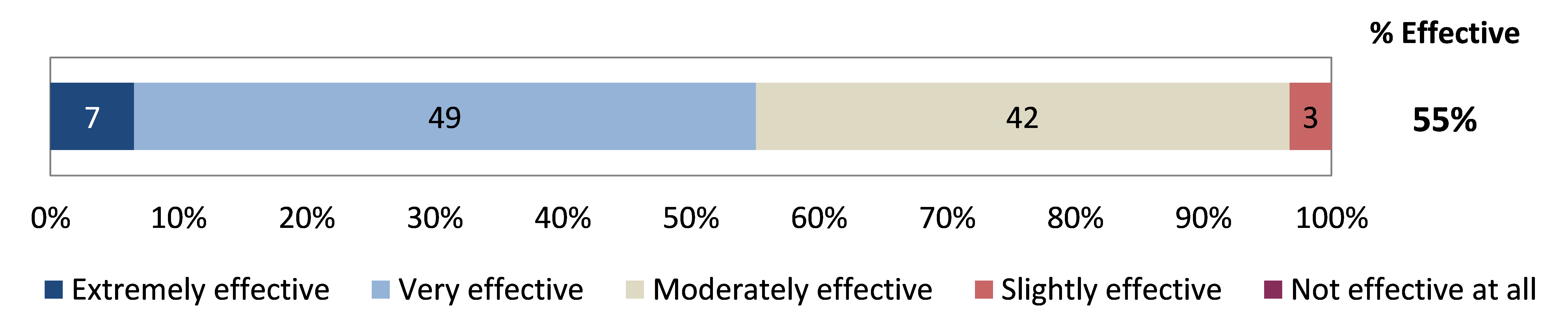

The Census results demonstrated that while the primary prevention workforce had completed training across a range of topic areas, overall confidence in their level of training and experience was moderate. The findings highlighted MARAM as a priority area for further/improved training and professional development.

Furthermore, the primary prevention workforce generally believed that dynamic/collaborative forms of additional support (i.e. information sharing, community of practice, mentoring / peer support) would be most useful in increasing their confidence in performing their role(s).

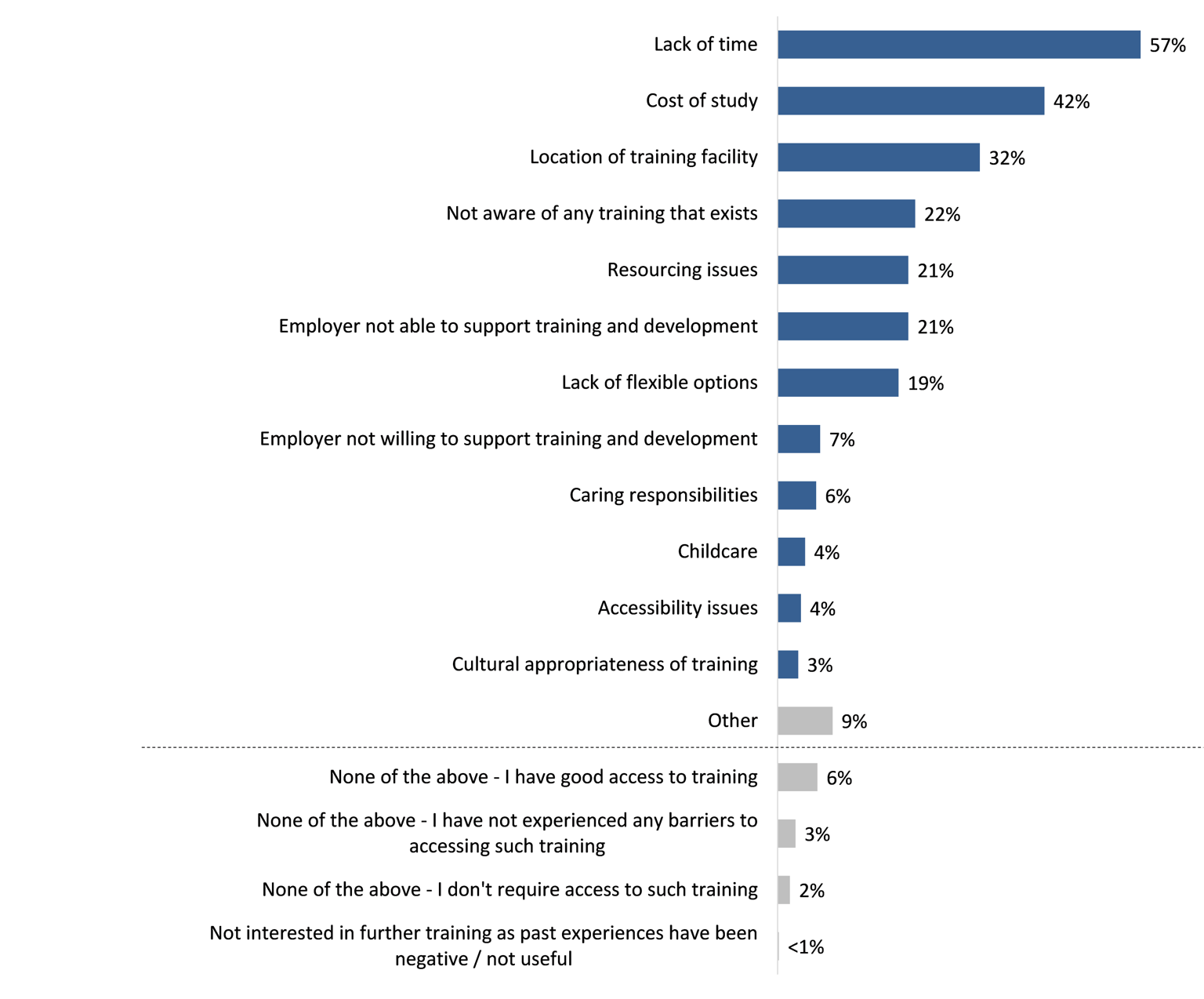

In terms of barriers to accessing further training and development, lack of time was the most commonly reported barrier, followed by cost of study and location of training facility.

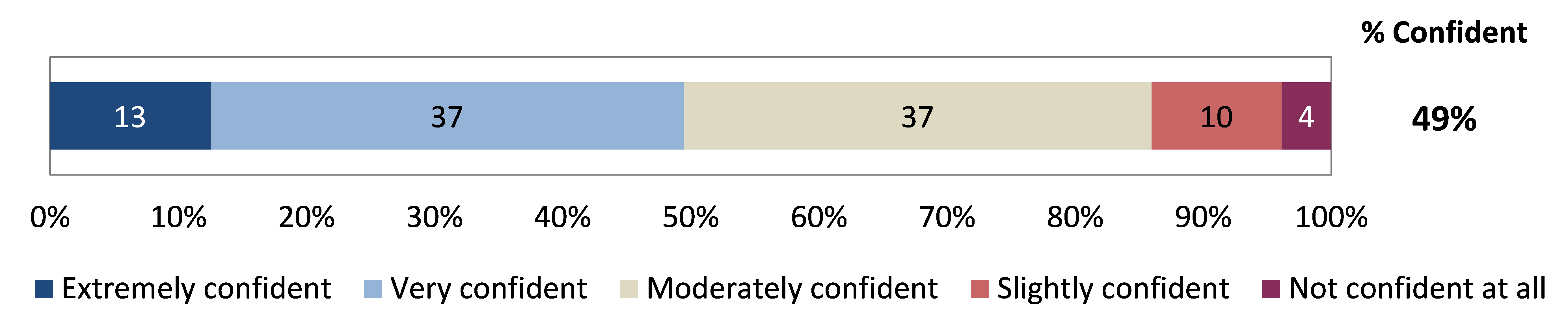

Confidence

Overall, around half of the primary prevention workforce indicated that they were ‘extremely’ or ‘very’ confident that they have had enough training and experience to perform their role(s) effectively (49%). In contrast, 14% reported that they were ‘slightly’ or ‘not at all’ confident.

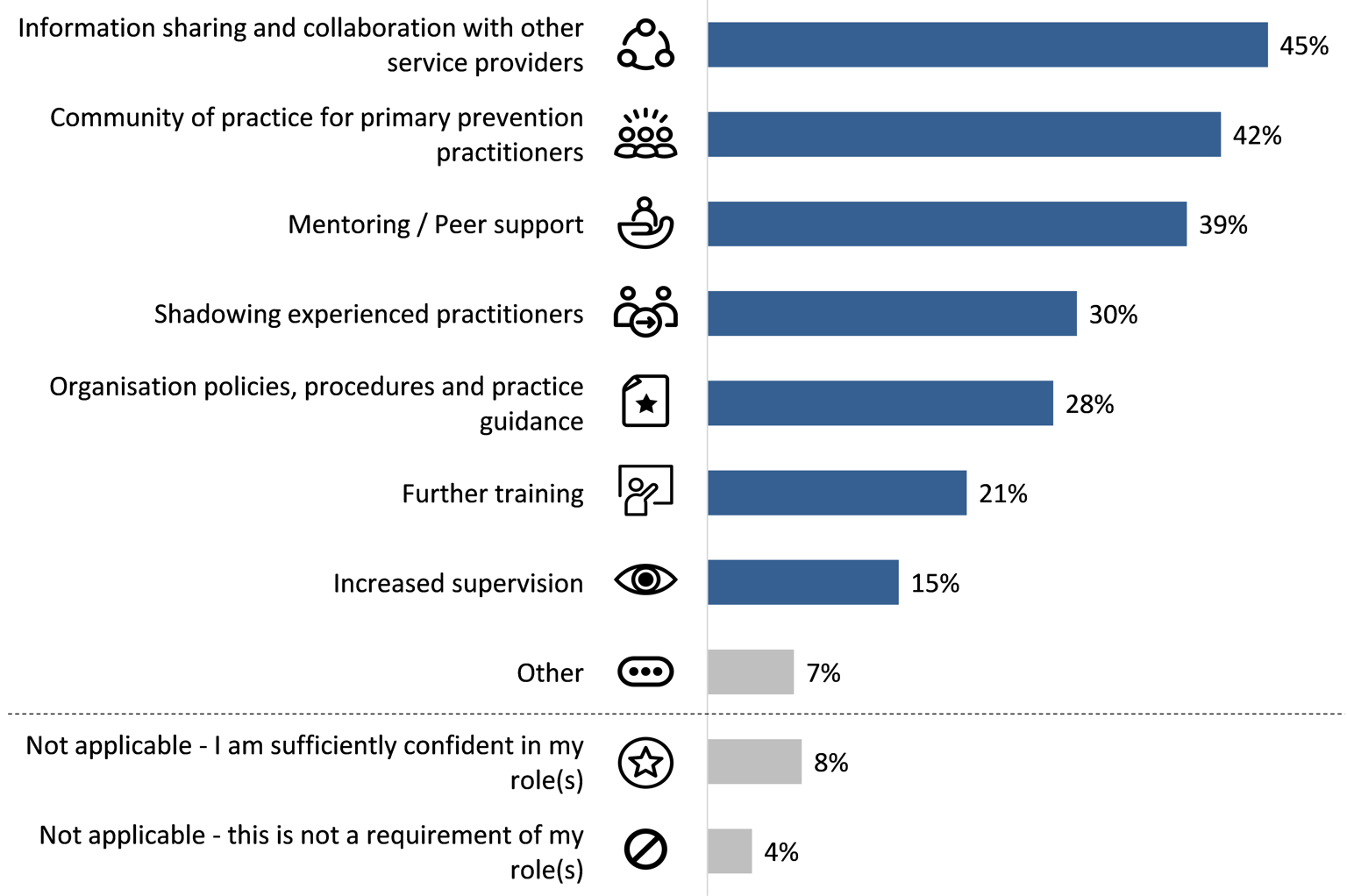

The primary prevention workforce felt that the following additional support would be most useful in increasing their confidence in performing their role(s) (see Figure 10):

- information sharing and collaboration with other service providers (45%);

- community of practice for primary prevention practitioners (42%); and

- mentoring / peer support (39%).

Conversely, respondents were least likely to indicate that further training or increased supervision would be beneficial in this context (21% and 15% respectively).

Results differed by age – younger respondents aged under 35 were considerably more likely than older respondents aged over 55 to report that they would benefit from shadowing experienced practitioners (45% versus 14%), mentoring / peer support (43% versus 25%), and organisation policies, procedures and practice guidance (34% versus 17%).

Overall, around one-fifth of the primary prevention workforce reported that they frequently respond to family violence disclosures (21% always or often).

Frequency varied across the following demographic cohorts:

- Years of experience – frequency increased with years of experience (11% for those with 1 year of experience or less, compared to 35% for those with over 10 years’ experience).

- Organisation type – response to family violence disclosures was most frequent among those employed in legal services (36%), multicultural or settlement services (31%), and community organisations (31%); and least frequent among those working in policy, research and advocacy (7%), and local council / government (10%).

MARAM

The family violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) framework provides guidance to organisations prescribed under regulations that have responsibilities in assessing and managing family violence risk.1 The framework is designed to ensure services are effectively identifying, assessing and managing family violence risk. A range of organisations were prescribed under MARAM in September 2018.

- 79% of the primary prevention workforce indicated that they had heard of the MARAM framework2; and of these,

- 52% understood that the organisation that they currently worked for was prescribed to align with the MARAM framework.3

By organisation type, the proportion of respondents who understood that their organisation was prescribed under MARAM was:

- highest among those working in school education (70%), community organisations (68%) and community health (63%); and

- lowest among those employed in health promotion (21%) and women’s health (26%).

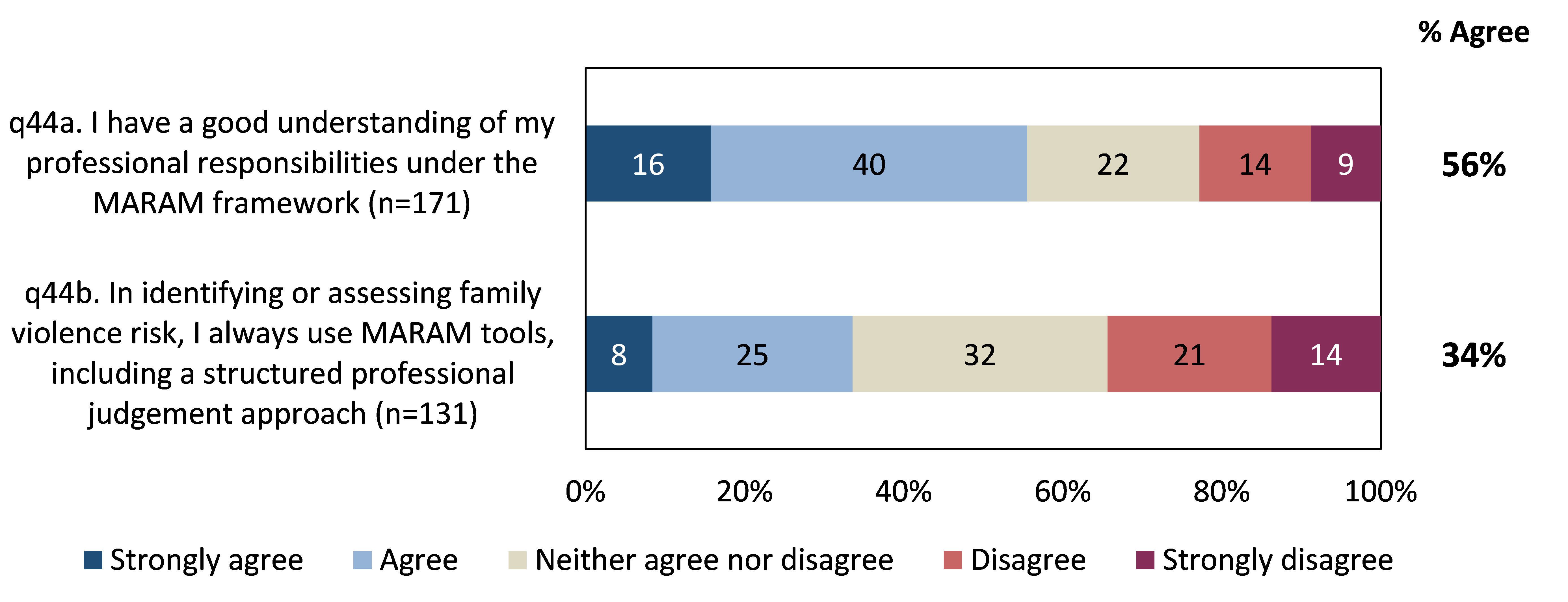

Of those who worked for organisations prescribed to align with the MARAM framework, in relation to identifying risk for victim survivors, understanding of one’s professional responsibilities under the framework was moderate (56%). Additionally, consistent usage of MARAM tools (including a structured professional judgement approach) in identifying or assessing family violence risk was relatively low (34%).

As outlined earlier, in primary prevention roles, employees may identify or receive disclosures of family violence.

- 53% of the primary prevention workforce reported that they had made a referral and / or shared information as a result of identifying or receiving a disclosure of family violence4; and of these,

- 60% felt that they had a ‘good’ or ‘very good’ understanding of their responsibilities to share information relating to family violence risk under relevant Information Sharing Schemes and privacy law.5

By organisation type, reported understanding of information sharing responsibilities was:

- highest among those employed in community organisations (74%); and

- lowest among those working in health promotion (33%) and policy, research and advocacy (35%) – these respondents were also more likely than others to report that they have never made a referral and/or shared information as a result of identifying or receiving a disclosure of family violence.

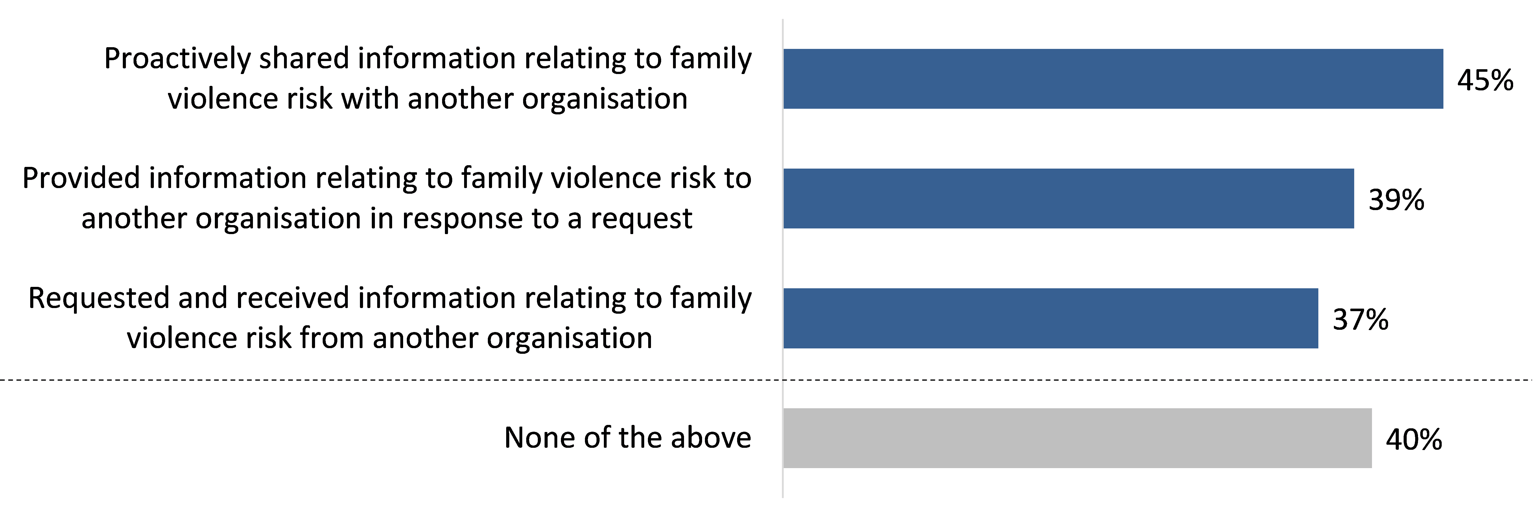

Figure 13 shows that conduct of information sharing activities under the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS) was moderate, with:

- the most common activity undertaken in the past year being the proactive sharing of information with another organisation (45%); and

- two-in-five indicating that they had not undertaken any information sharing activities under the FVISS in the past year (40%).

Footnotes

- Family Violence Multi Agency Risk Assessment and Management

- Q42. Before today, had you heard of the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) framework? (n=474)

- Q43. Is the organisation that you work for in your current role prescribed to align with the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) framework? (n=373)

- Q45. Have you ever made a referral and/or shared information as a result of identifying or receiving a disclosure of family violence? (n=467)

- Q46. Please rate your understanding of your responsibilities to share information relating to family violence risk under the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS), Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS) and relevant privacy law. (n=210)

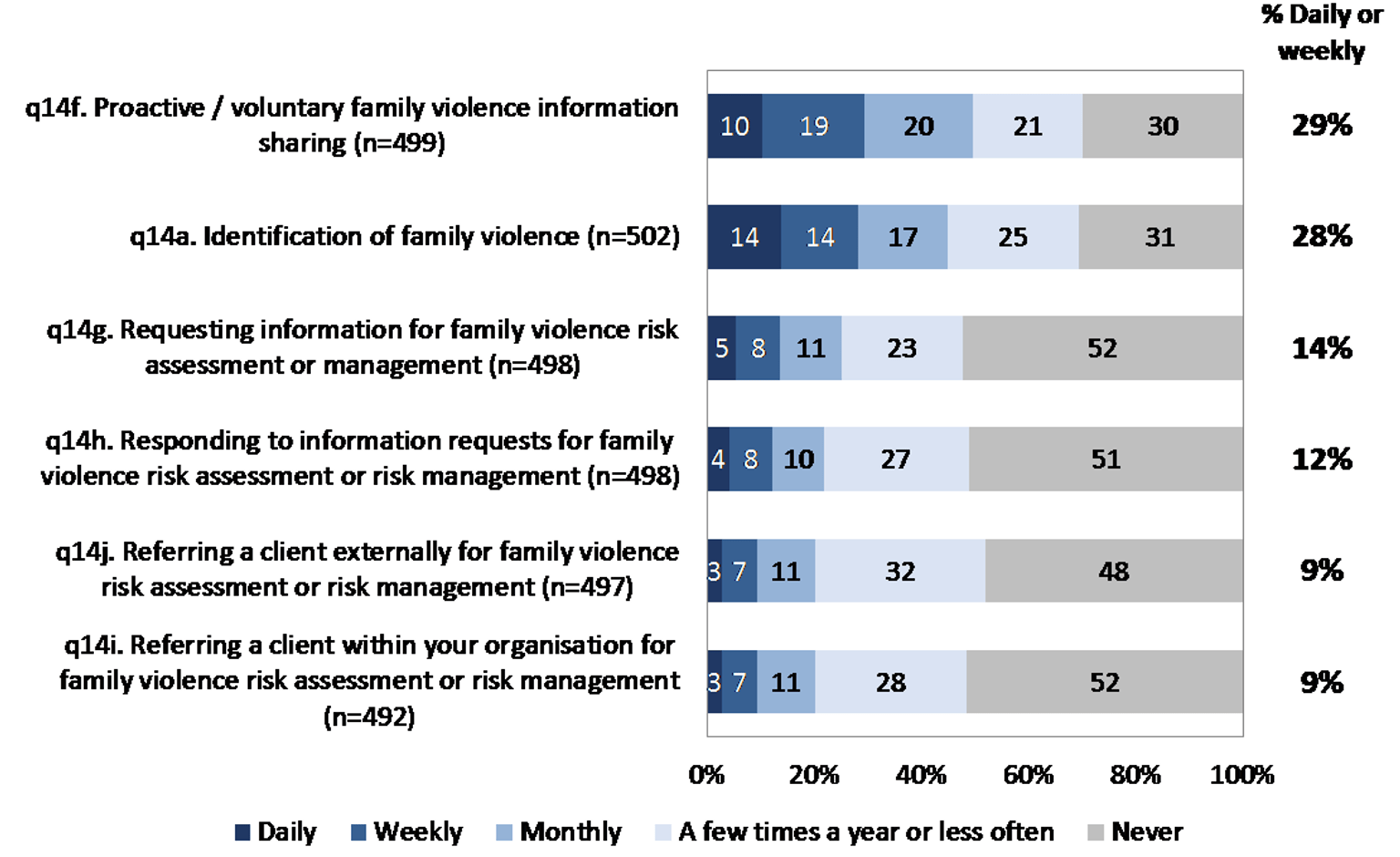

Training

The primary prevention workforce was asked to identify both the family violence prevention and response topics they had completed training in, and those they would like further training in.

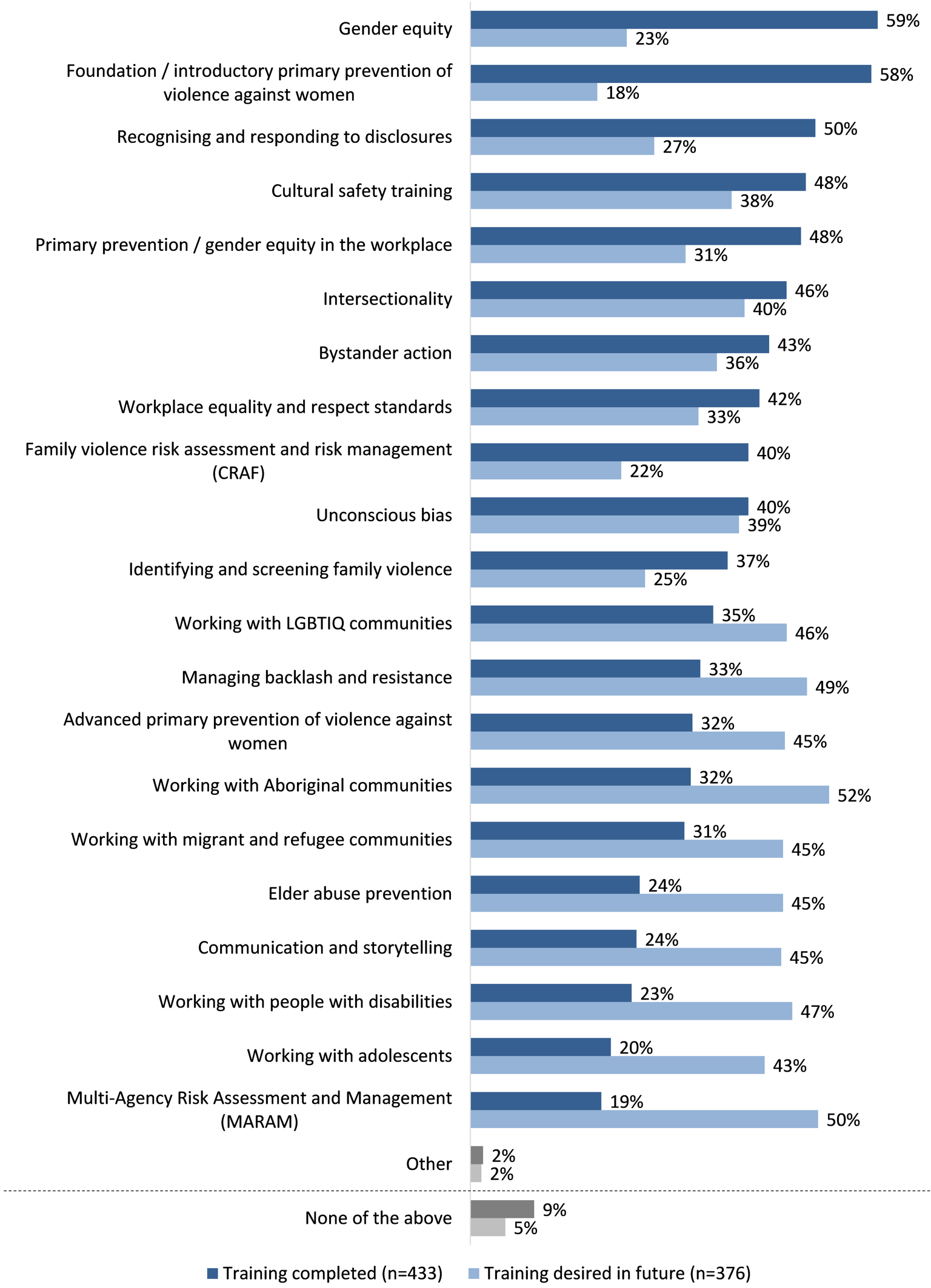

As illustrated in Figure 14 , at least half of respondents had completed training in relation to:

- gender equity (59%);

- foundation / introductory primary prevention of violence against women (58%); and

- recognising and responding to disclosures (50%).

The topics which respondents felt they required further training in were generally those with lower completion rates, including training related to:

- working with Aboriginal communities (32% had completed training, 52% desired further training);

- MARAM (19% had completed training, 50% desired further training); and

- managing backlash and resistance (33% had completed training, 49% desired further training).

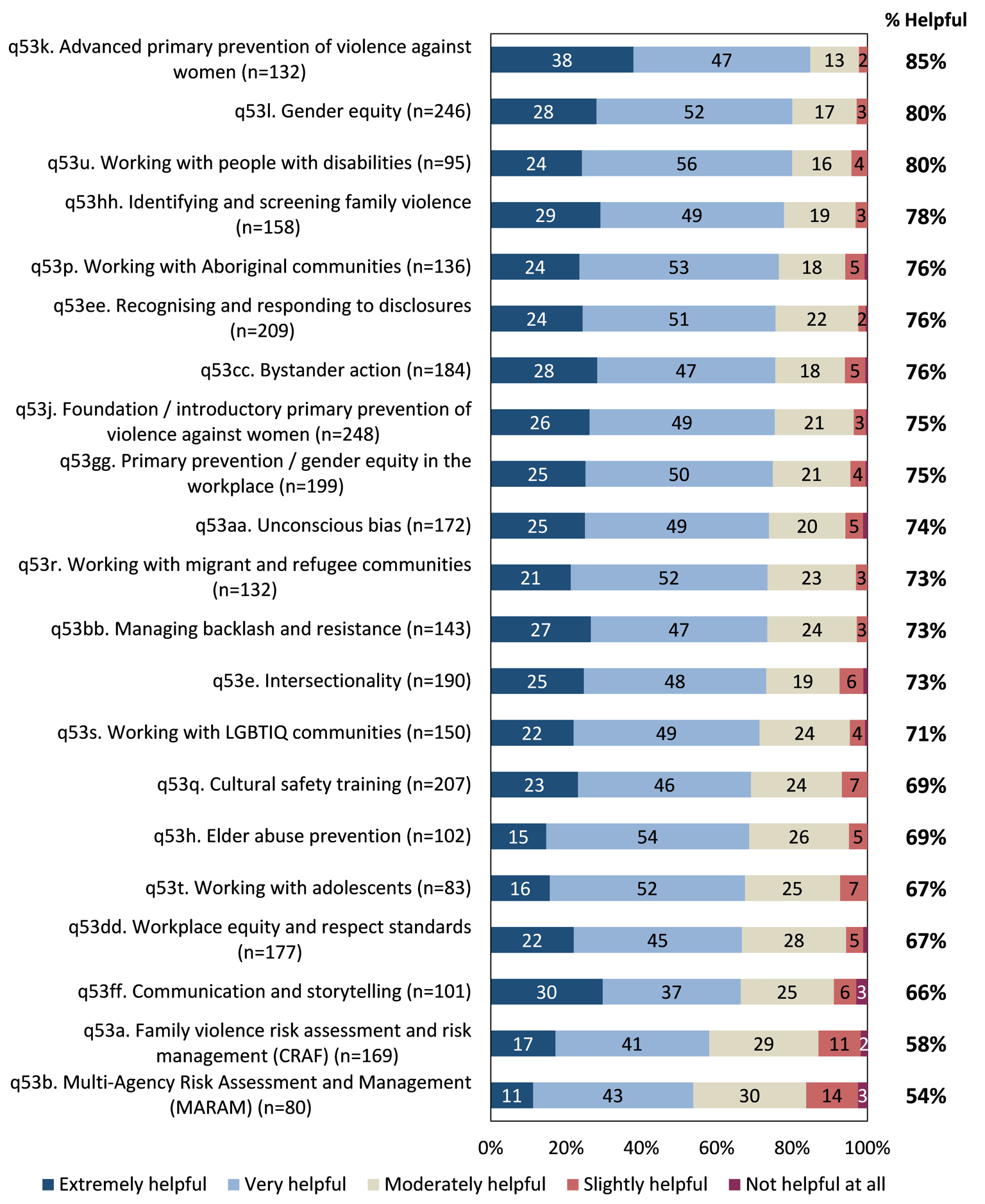

Those who had completed training in each topic area were then asked to assess the degree to which they believed the training had assisted them in undertaking their work more effectively. Figure 15 (see page 29) shows that perceived helpfulness was relatively high across most topic areas, and was highest in relation to training in:

- advanced primary prevention of violence against women (85% found training in this topic to be ‘extremely’ or ‘very’ helpful);

- gender equity (80%); and

- working with people with disabilities (80%).

In contrast, respondents were least likely to feel that training undertaken in the following topics was helpful:

- communication and storytelling (66% – although a notable proportion (30%) found training to be ‘extremely’ helpful);

- family violence risk assessment and risk management (CRAF – 58%); and

- MARAM (54%).

These results suggest that there is an opportunity to review and improve training in various topics, particularly those related to frameworks guiding the primary prevention workforce (e.g. CRAF and MARAM). This review may include further investigation into whether existing training offerings are fit for purpose, or whether they need to be adapted for the primary prevention workforce.

When asked about barriers to accessing further training and development in relation to family violence response or prevention, the three main barriers identified by respondents were:

- lack of time (57%);

- cost of study (42%); and

- location of training facility (32%).

Health and wellbeing

This chapter explores the impacts of primary practitioners’ work on their health and wellbeing.

Health and wellbeing is an important area of focus for all workforce types, however should be of particular focus for this workforce given various work-related stressors they may encounter. The information in this chapter may be used to improve understanding of the health and wellbeing of the workforce as a whole, assist in identifying any specific areas of focus, and inform forward-looking strategies to support its workers.

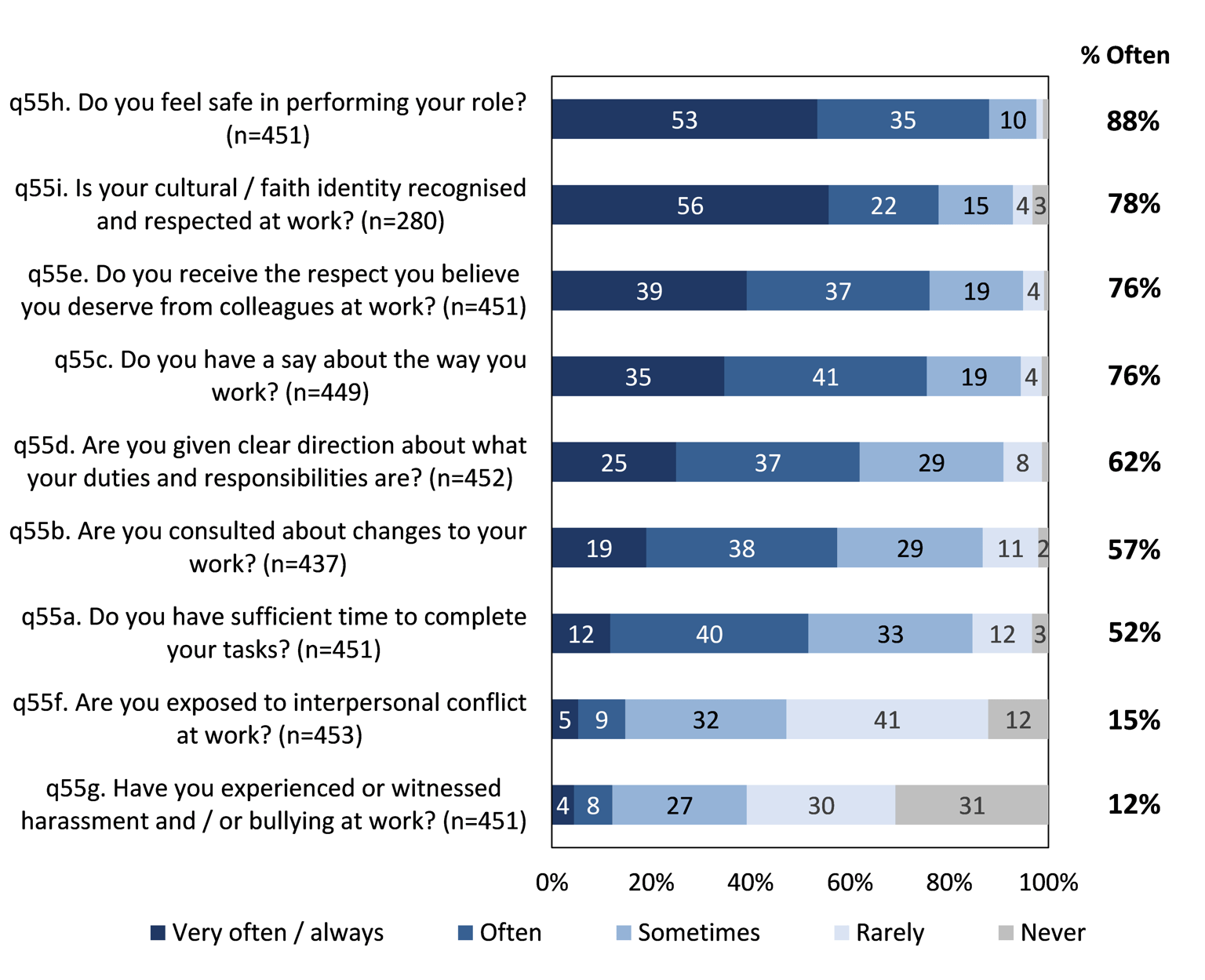

Overall, the results of both the Census and the initial consultation phase of the project suggested that many within this workforce experience stress due to high workload, with around half reporting that they only sometimes had sufficient time to complete their tasks.

Positive findings included the fact that most of the workforce indicated that they felt safe in performing their role, and many felt respected and fairly consulted when undertaking their work. Additionally, few were dissatisfied in their current role and most felt that they made a difference to people affected by family violence (45% felt they made a significant difference).

Satisfaction with role

Footnotes

- Q56. On average, how would you rate your level of work-related stress? (n=458)

- Q57. What is the primary cause(s) of your work-related stress? Multiple responses accepted (n=142)

- Backlash and resistance refer to any form of resistance toward gender equality.

- Q61. In your role, how often do you experience resistance or backlash in undertaking your work? (n=454)

- Q63. Do you have access to support to assist you if you encounter cases of family violence or disclosures, or resistance or backlash in your work? (n=400)

- Q67. How much difference do you think your work makes to people affected by family violence? (n=397)

Career and future intentions

This chapter discusses what it is that motivates the primary prevention workforce in their careers and explores their future plans/ intentions. Such information can be useful to inform recruitment and retention strategies to improve the workforce as a whole.

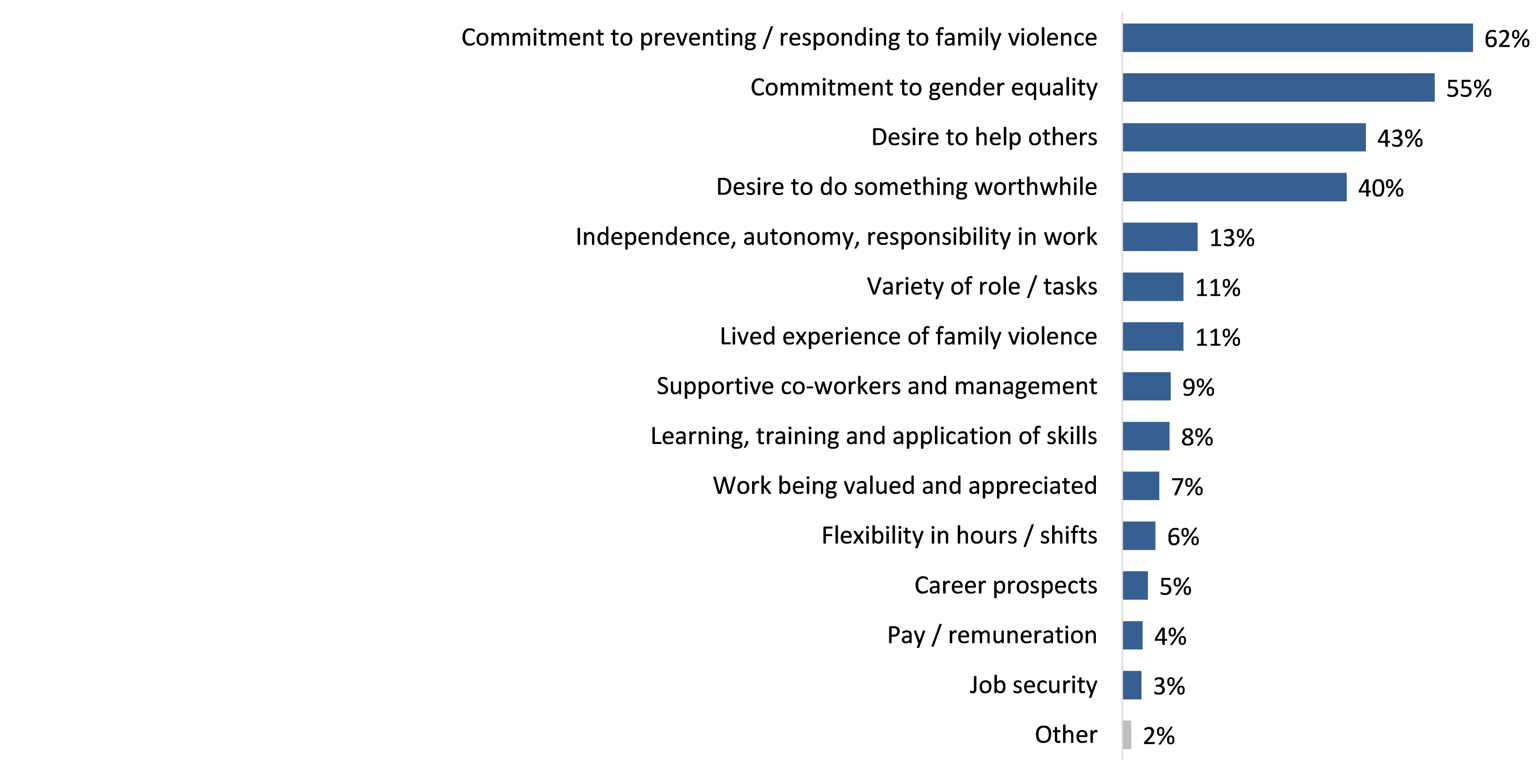

Overall, the results illustrated that the primary prevention workforce shared a number of positive reasons for working in the primary prevention workforce, including a strong commitment to preventing/responding to family violence and gender equity.

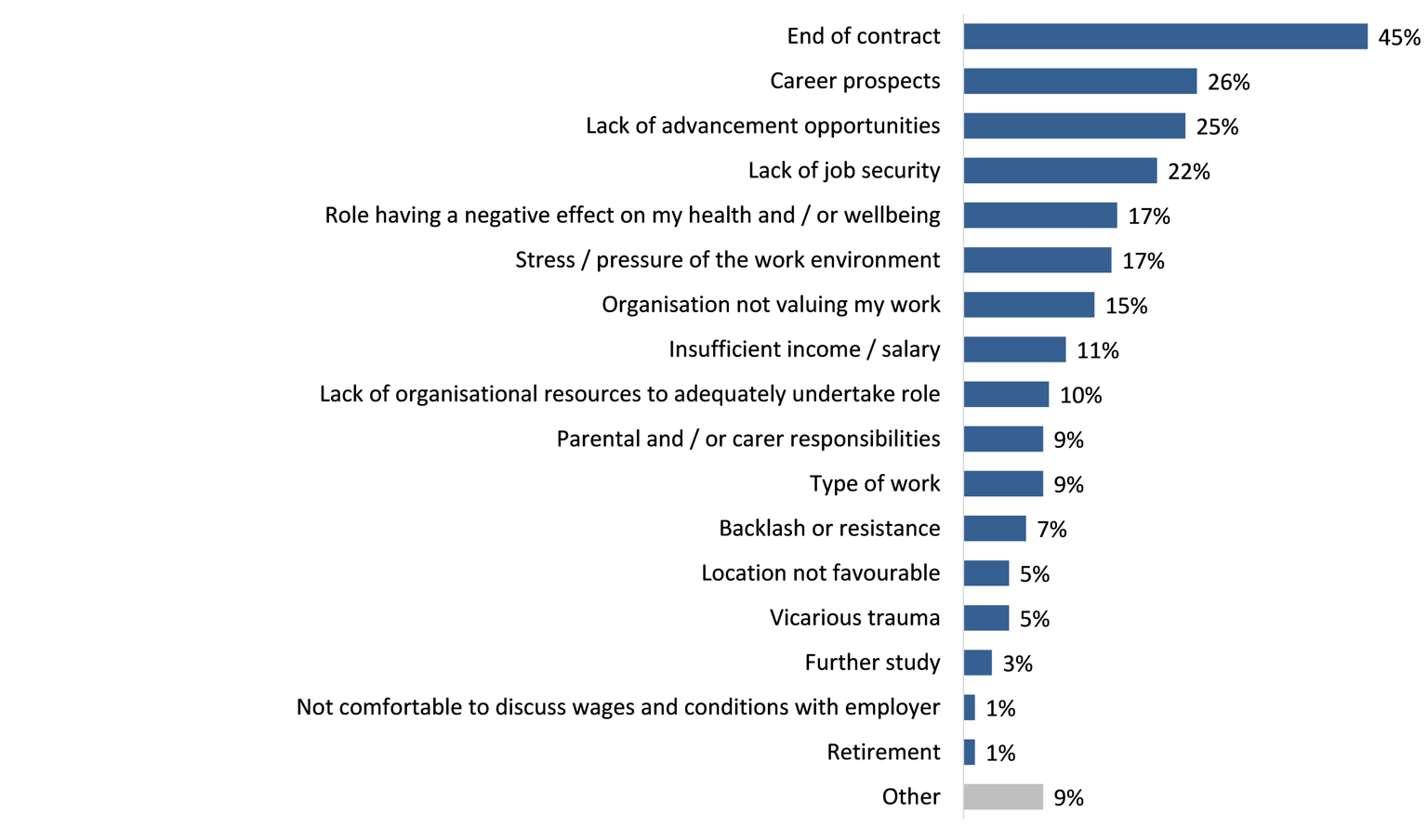

Regarding future intentions, almost half of all primary prevention practitioners reported that they had plans to leave their current role. Although many planned to do so due to an end of contract, others were influenced by better career prospects and lack of advancement opportunities.

When asked what mainly motivates them to work in their primary prevention role, a commitment to preventing and responding to family violence, as well as to gender equity, were the most common reasons cited (55%-62% – see Figure 22). Around four-in-ten respondents were also motivated by a desire to help others (43%) and do something worthwhile (40%). This workforce was least motivated by job security (3%), pay/remuneration (4%) and career prospects (5%).

Before commencing their current role in the primary prevention workforce, just over one-third had held a role working for another organisation or agency in the sector (within Victoria – 35%). Around one-quarter (26%) had been working in a related sector, whilst 16% had been working in an unrelated sector, illustrating the diversity of this workforce in terms of career pathways and trajectories.

Footnotes

- Q71. Thinking about your future, do you have plans to leave your current role? (n=446)