- Date:

- 11 Aug 2020

Research team and acknowledgements

Research team and Acknowledgements for Review of the Family Violence Information Sharing Legislative Scheme Final Report.

Research team

Professor Jude McCulloch

Criminology, Director of the Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre

Professor JaneMaree Maher

Sociology, Centre for Women’s Studies and Gender Research, Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre

Dr Kate Fitz-Gibbon

Senior Lecturer, Monash University, School of Social Sciences, Criminology. Key researcher, Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre

Associate Professor Marie Segrave

Monash University, School of Social Sciences, Criminology

Dr Kathryn Benier

Lecturer, Monash University, School of Social Sciences, Criminology

Dr Kate Burns

Lecturer, Monash University, School of Social Sciences, Criminology

Dr Jasmine McGowan

Centre Manager, School of Social Sciences, Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre

Dr Naomi Pfitzner

Research Fellow, School of Social Sciences, Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre

Suggested citation

McCulloch J., Maher, J., Fitz-Gibbon, K., Segrave, M., Benier, K., Burns, K., McGowan, J. and N., Pfitzner (2020) Review of the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme Final Report. Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre, Faculty of Arts, Monash University.

Acknowledgements

The Review team wishes to extend our thanks to victim/survivors who shared their stories with us. It is increasingly recognised that ‘having a voice’ is an important part of achieving justice for those who have experienced violence and human rights abuses. The voices of victims/survivors are critical to ensuring that family violence reforms meet the goal of better security and safety for those experiencing family violence and improving perpetrator accountability.

Many of the women who had experienced violence who took part in this Review expressed the hope that their participation would assist to bring positive change. We want to thank all those workers and managers involved in the Family Violence Information Sharing reforms who generously shared their time with us. The wide-ranging family violence reforms have increased service demand and required enormous sustained commitment from those involved. We are sincerely grateful that time poor workers and managers were willing to make time to contribute to the Review.

We also extend our thanks to those at Family Safety Victoria who generously assisted to facilitate the Review. Rachael Green, Director Risk Management and Information Sharing, was always willing to openly discuss the challenges and opportunities and assist with the Review. David Floyd, Manager Risk Management and Information Sharing, provided constructive feedback at all stages of the Review. Joanna O’Donohue, Senior Policy Officer Risk Management and Information Sharing, played a critical role in providing the Review with information and assisting with participant recruitment.

We want to thank all board members, academic members and researchers in the Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre including, Dean of Arts, Professor Sharon Pickering, Professor Anne Edwards AO, the Hon. Professor Marcia Neave AO, Christine Nixon APM, Professor Sandra Walklate, Associate Professor Silke Meyer, Dr Tess Bartlett and Jessica Burley.

Thank you to Tommy Fung, School of Social Sciences Finance Manager, who provided valuable support. Thank you also to Vanja Radojevic and Bev Baugh in the Arts Faculty research office who provided critical support and advice throughout the project.

Abbreviations

Abbreviations used in the Family Violence Information Sharing Legislative Scheme Final Report.

|

ACCO |

Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations |

|

ACT |

Australian Capital Territory |

|

AFM |

Affected Family Member |

|

ANROWS |

Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety |

|

AOD |

Alcohol and Other Drugs |

|

CALD |

Culturally and Linguistically Diverse |

|

CIP |

Central Information Point |

|

CISS |

Child Information Sharing Scheme |

|

COAG |

Council of Australian Governments |

|

CRAF |

Common Risk Assessment Framework |

|

CRM |

Client Relationship Management |

|

CVRC |

Corrections Victoria Research Committee |

|

DET |

Department of Education and Training |

|

DHHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

DJCS |

Department of Justice and Community Safety |

|

DVRCV |

Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria |

|

EI |

Expert Interview |

|

FG |

Focus Group |

|

FOI |

Freedom of Information |

|

FSV |

Family Safety Victoria |

|

FVISS |

Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme |

|

HS |

Homelessness Service |

|

ISE |

Information Sharing Entity |

|

ISTA |

Information Sharing Training Approach |

|

LGBTIQ |

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, intersex and/or queer |

|

MARAM |

Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management |

|

MBCP |

Men’s Behaviour Change Program |

|

MGFVPC |

Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre |

|

MUHREC |

Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee |

|

RAE |

Risk Assessment Entity |

|

RAMP |

Risk Assessment and Management Panel |

|

RCFV |

Royal Commission into Family Violence |

|

SWFVS |

Specialist Women’s Family Violence Services |

|

SMFVS |

Specialist Men’s Family Violence Services |

|

TAS |

Tasmania |

|

UK |

United Kingdom |

|

VPS |

Victorian Public Service |

List of tables

List of tables in the Family Violence Information Sharing Legislative Scheme Final Report.

Table 1: Stages of FVISS Implementation

Table 2: FVISS Review Questions

Table 3: Evaluation Framework

Table 4: FVISS Review Participation

Table 5: Survey One and Two Survey Respondents

Table 6: Evaluation Timeline

Table 7: Additional Support Priorities for FVISS Implementation into the Future

Table 8: Family Violence Risk Information Sharing Practices

Table 9: Agency Specific Sharing

Table 10: How Information is Shared

Table 11: Survey Two respondent views on Information Sharing Practices

List of figures

List of figures used in the Family Violence Information Sharing Legislative Scheme Final Report.

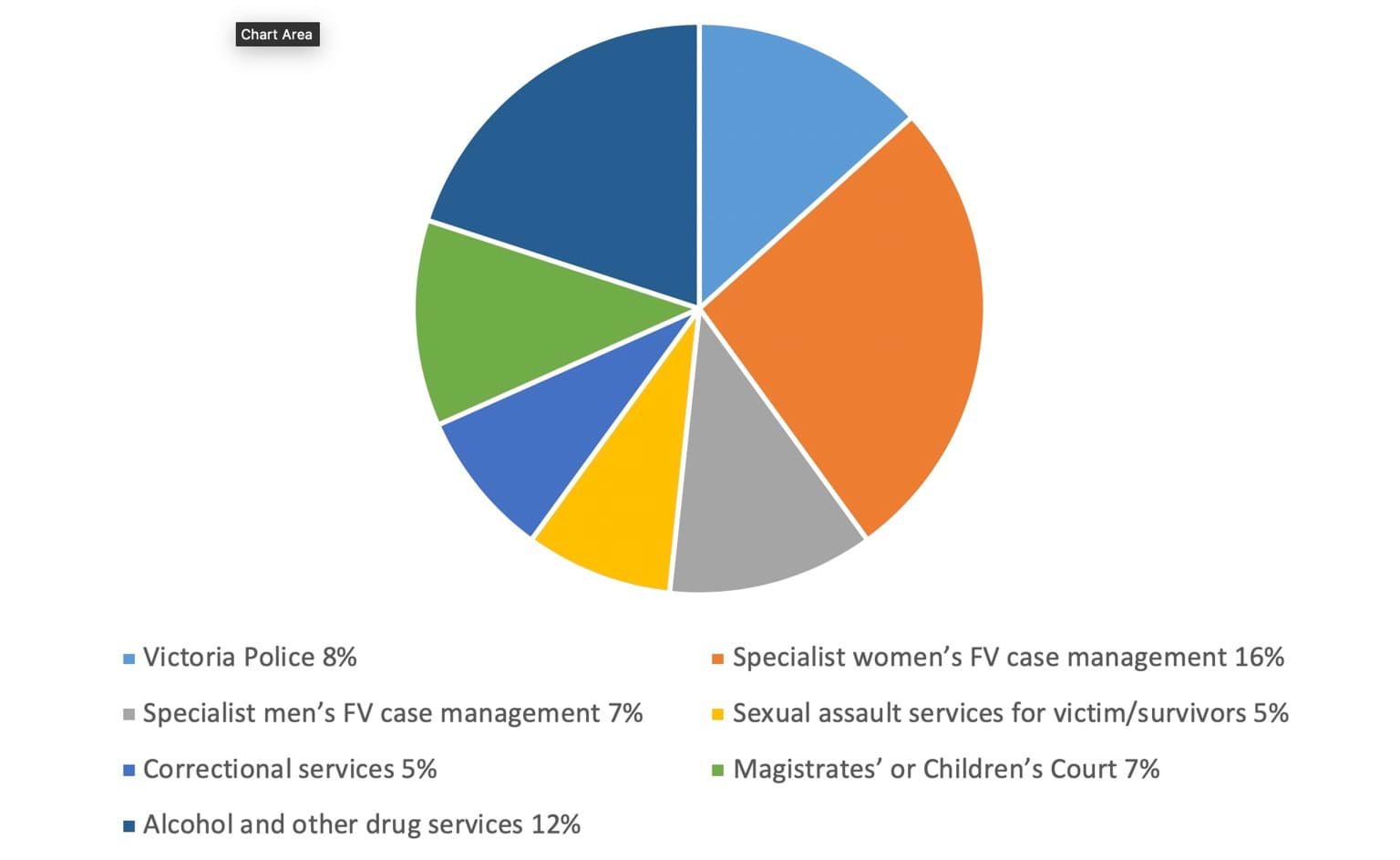

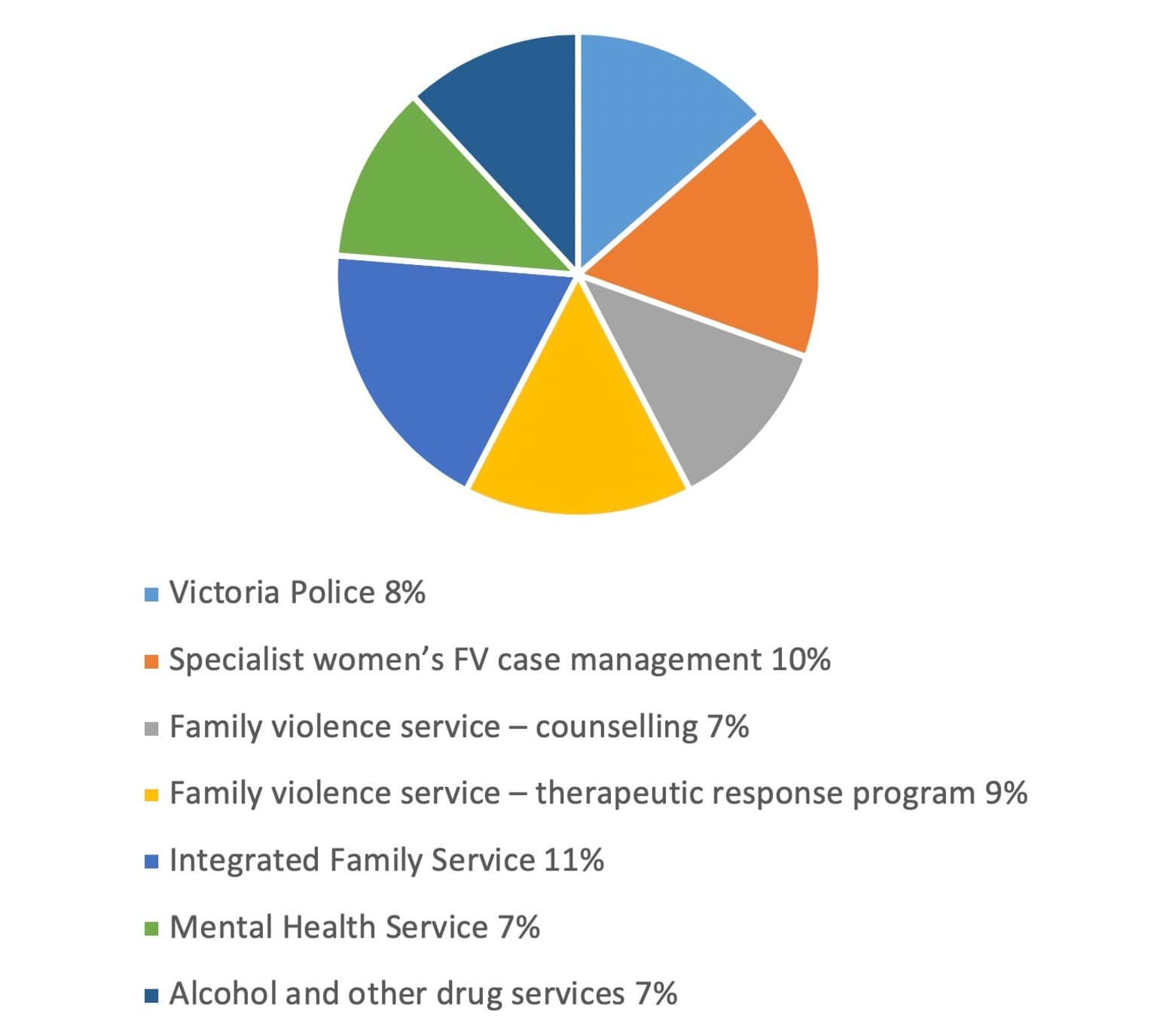

Figure 1: Summary of FVISS Review Methodology

Figure 2: Percentage of respondents by workplace (Survey one)*

Figure 3: Percentage of respondents by workplace (Survey two)*

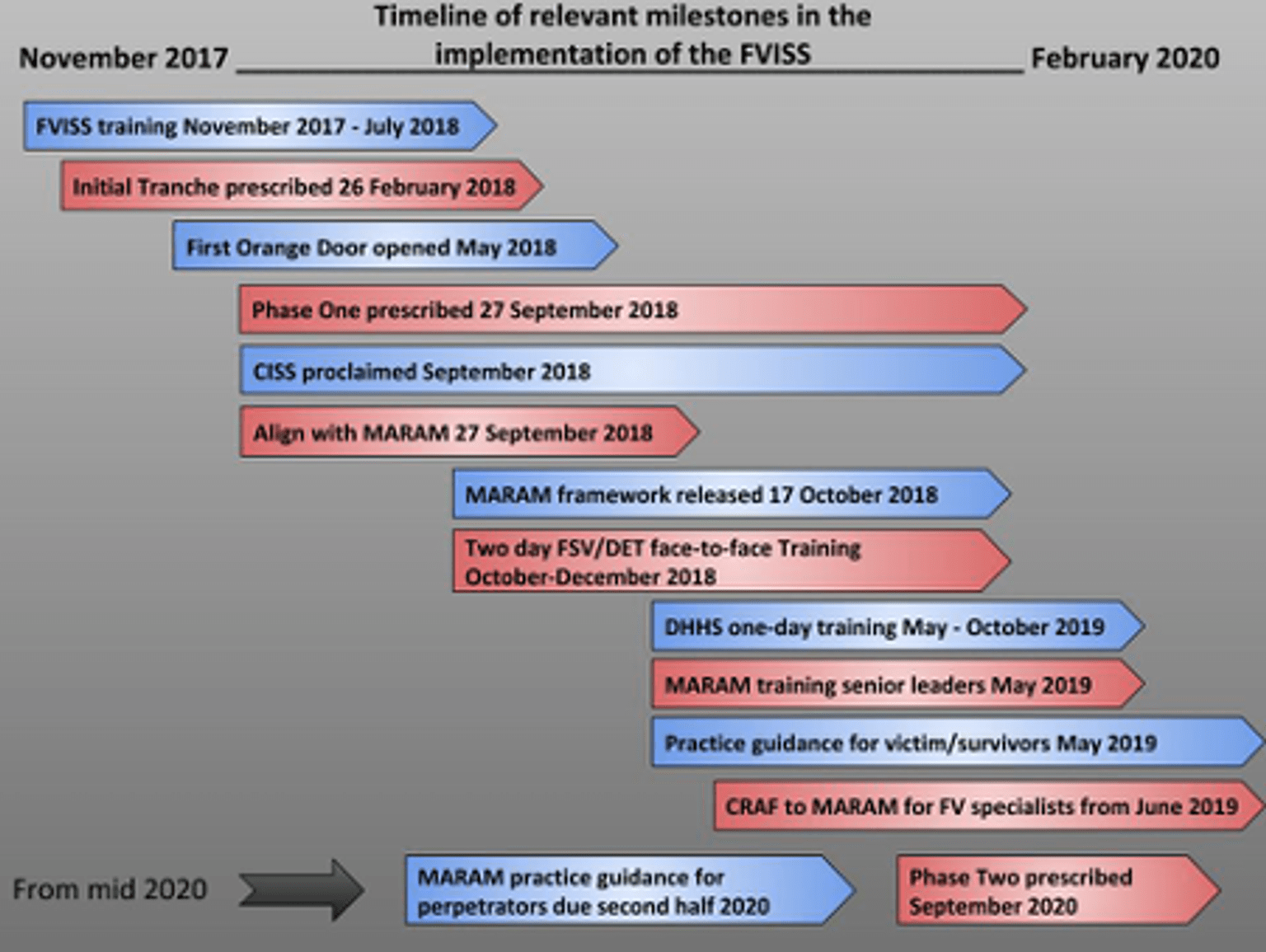

Figure 4: Timetable of relevant milestones in the implementation of the FVISS

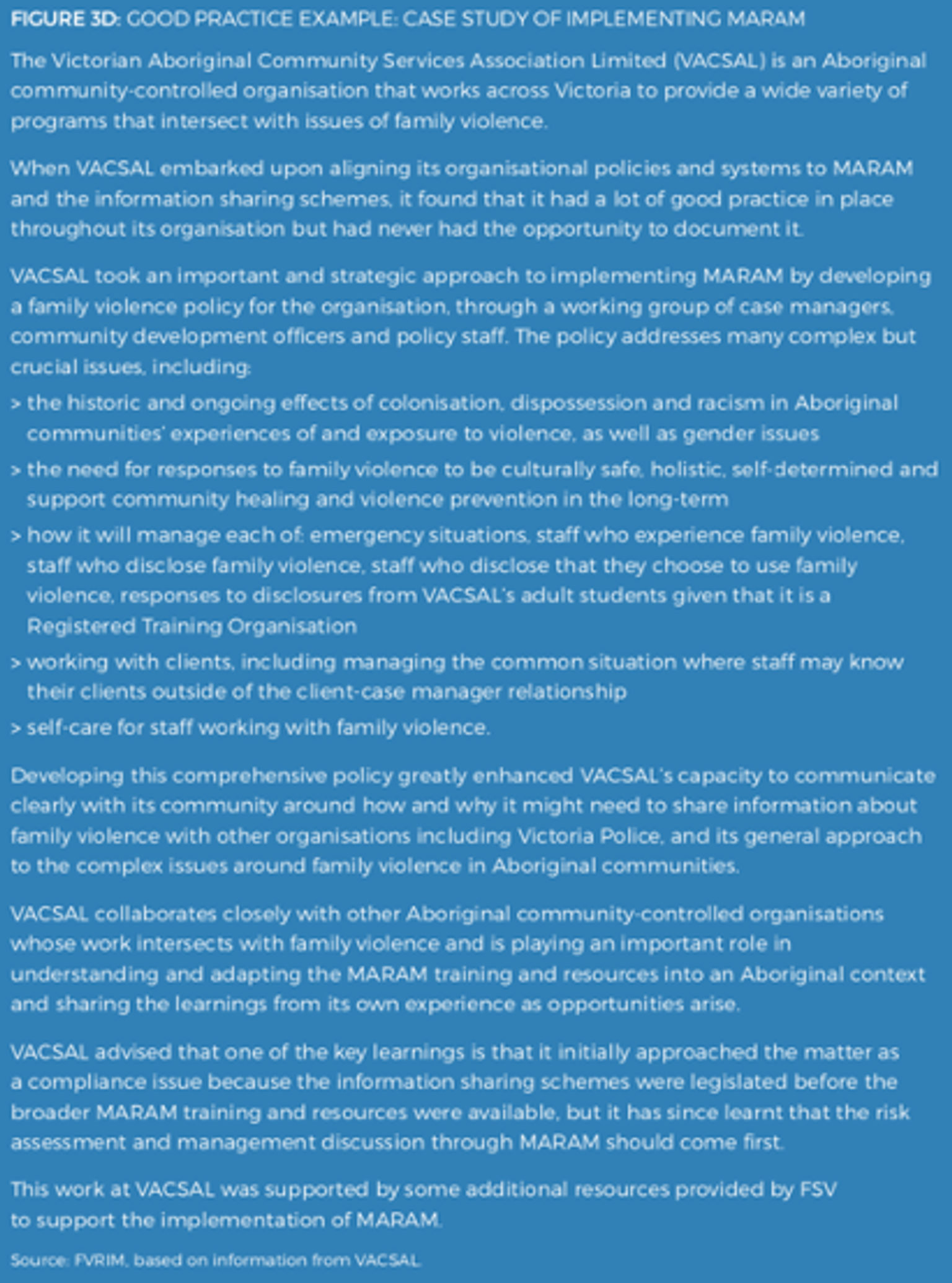

Figure 5: Good Practice Example: Case Study of Implementing MARAM and the information sharing schemes

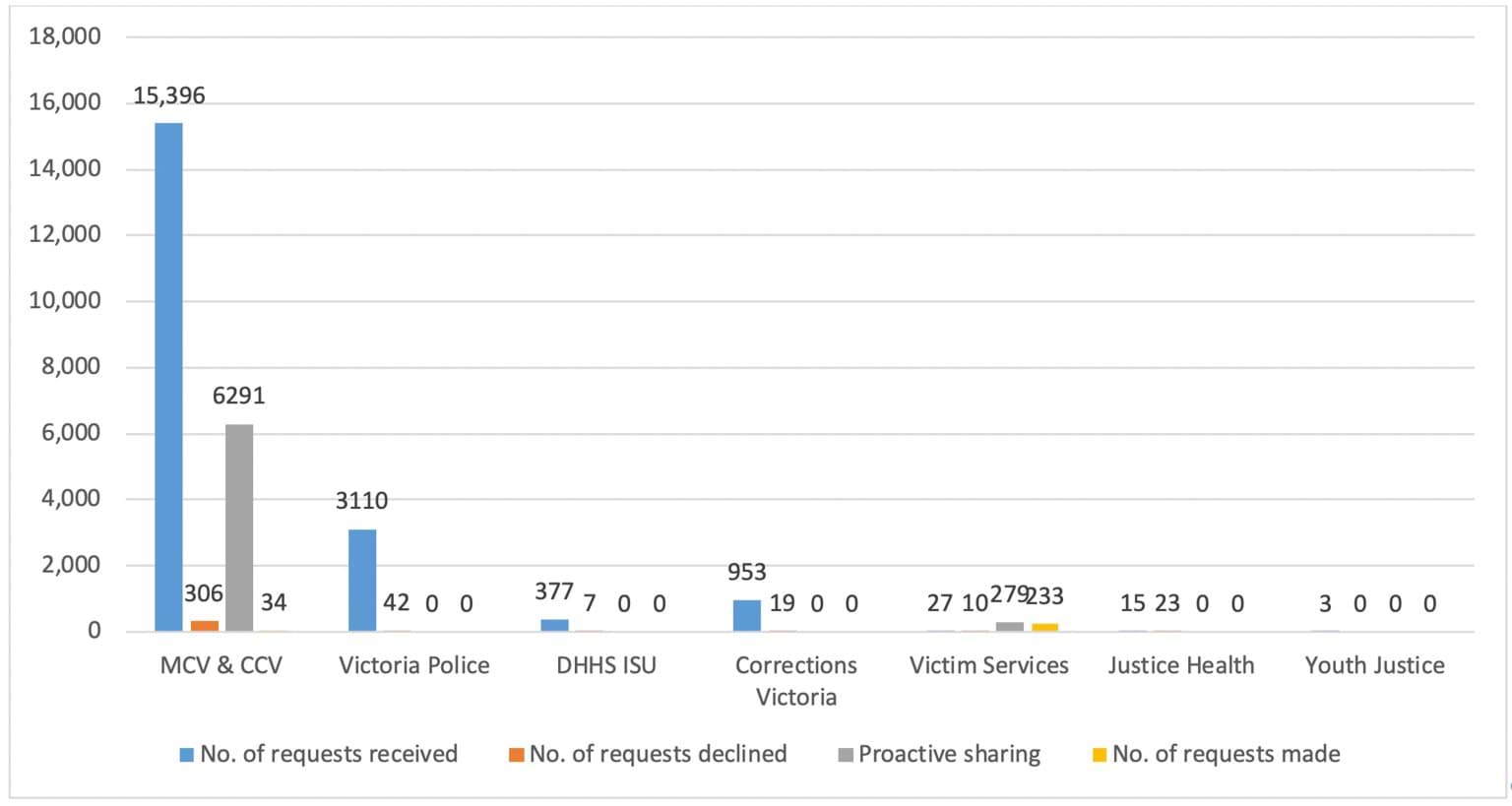

Figure 6: Scheme to Data Agency Comparison of Responses to Information Requests

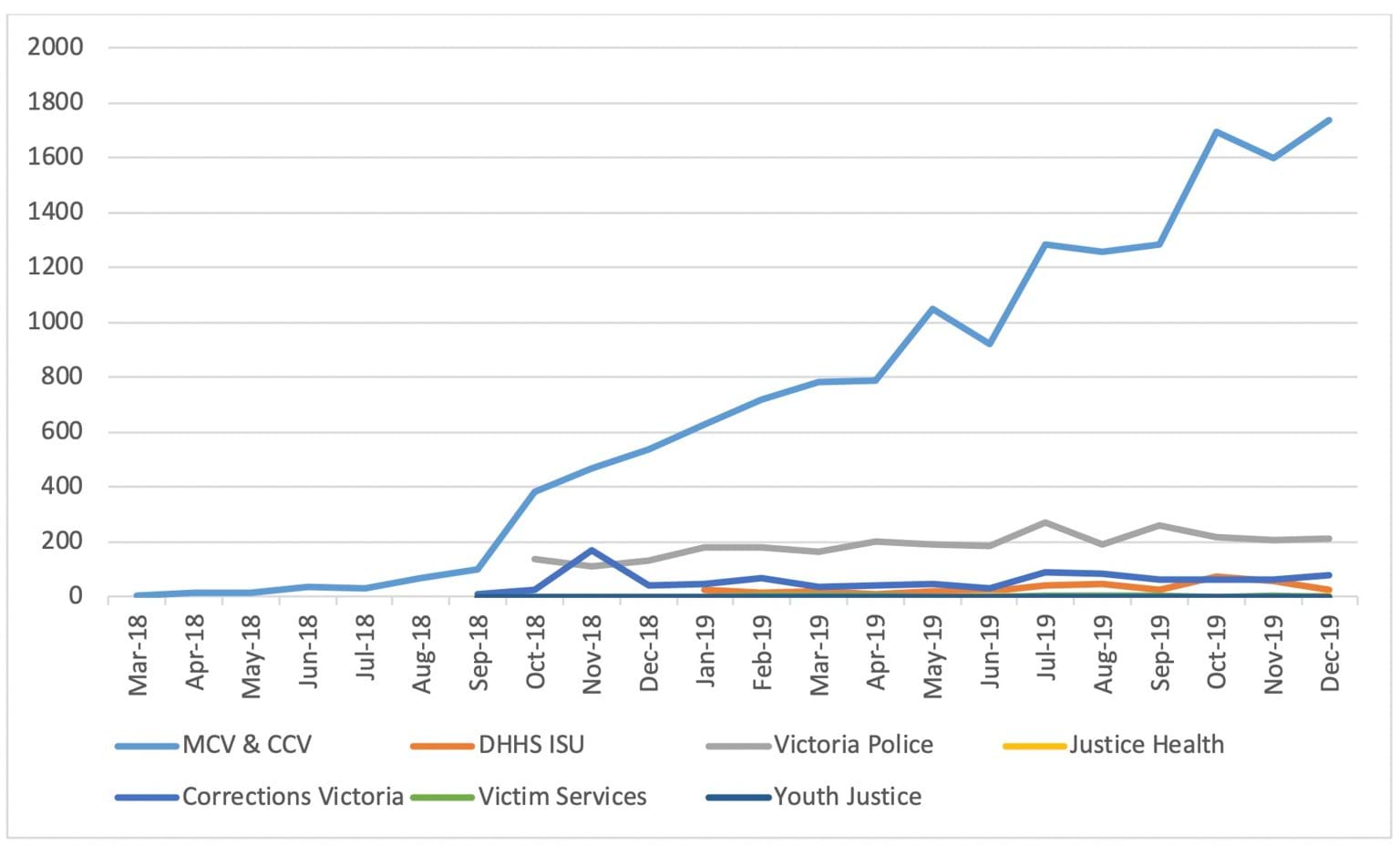

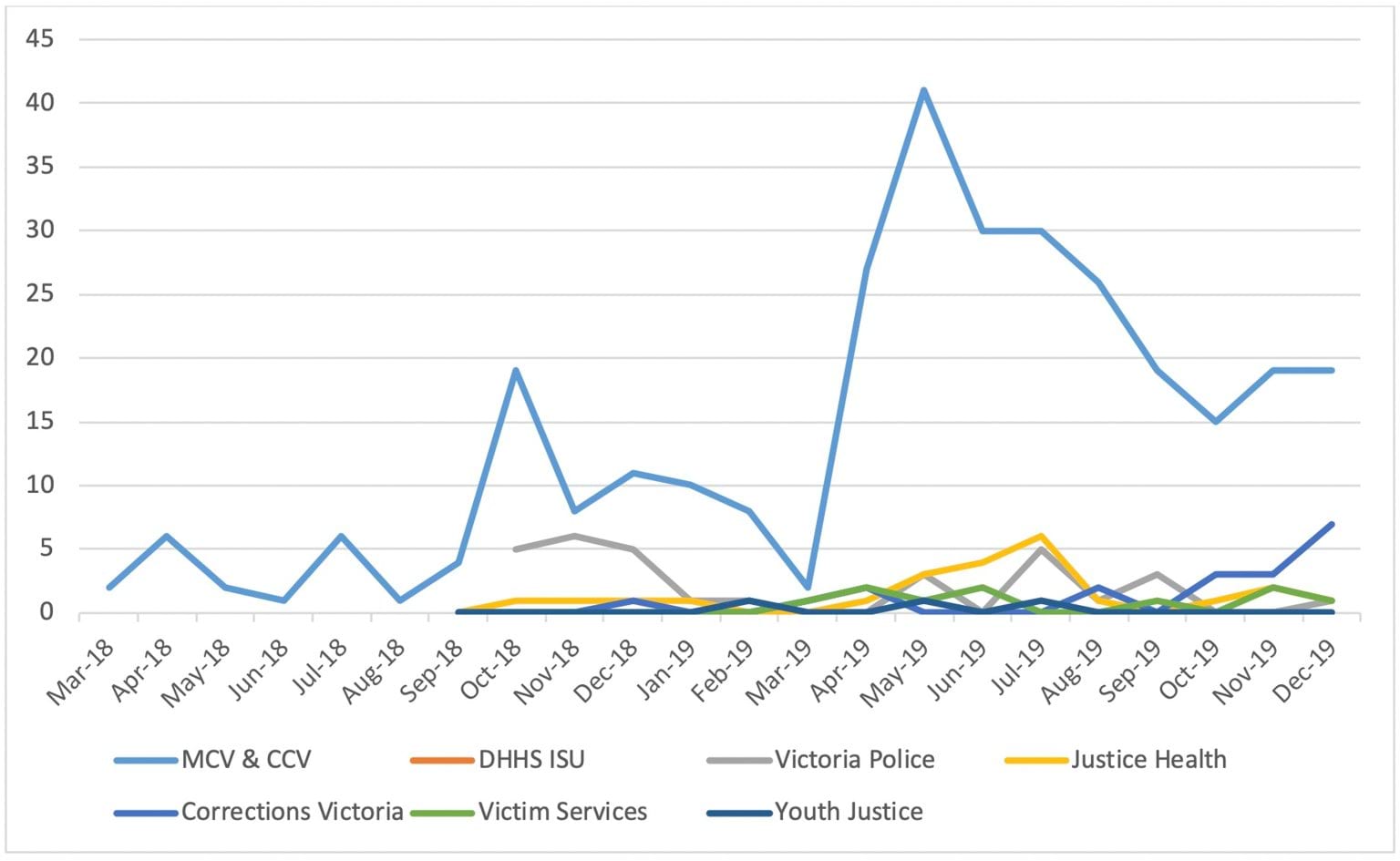

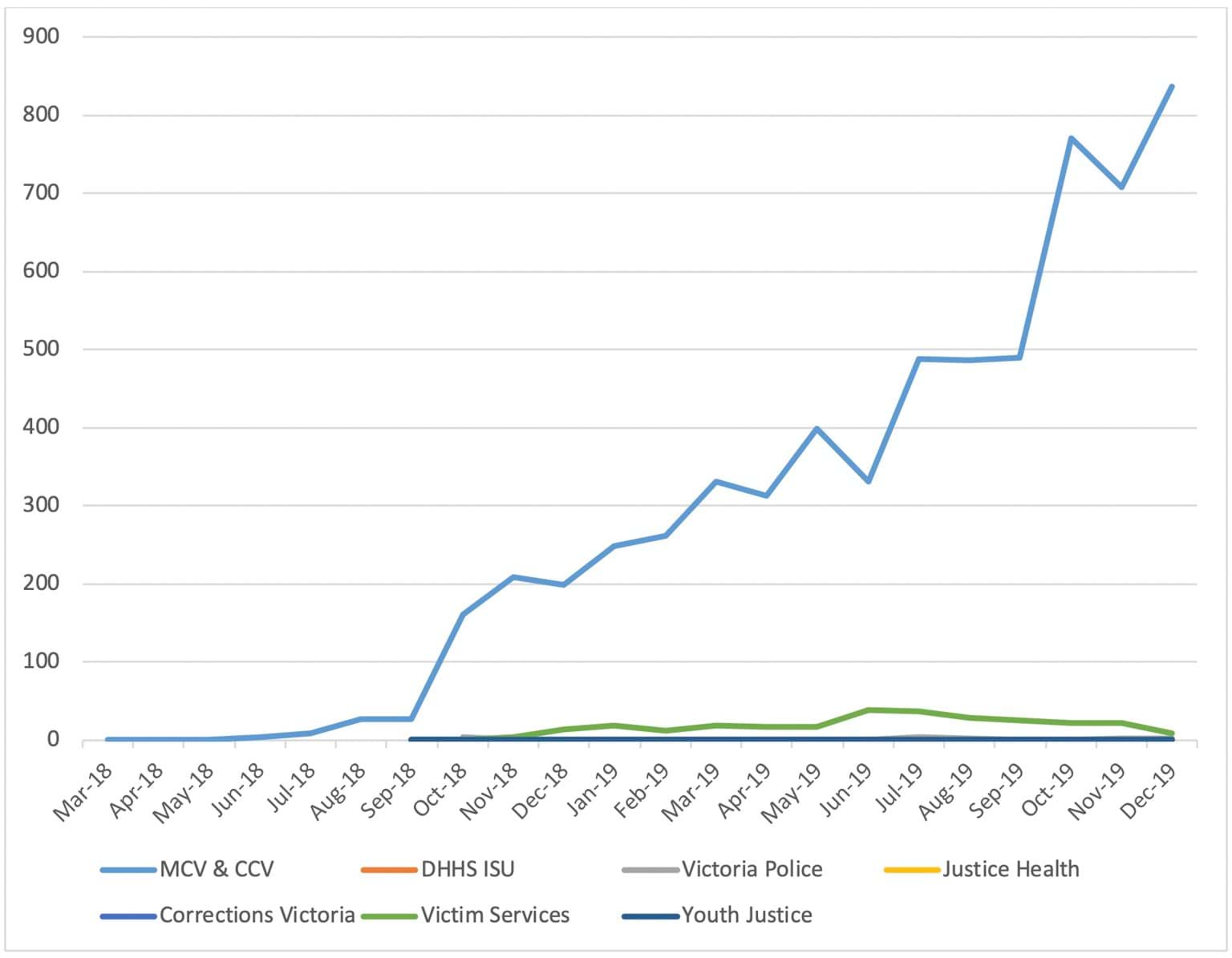

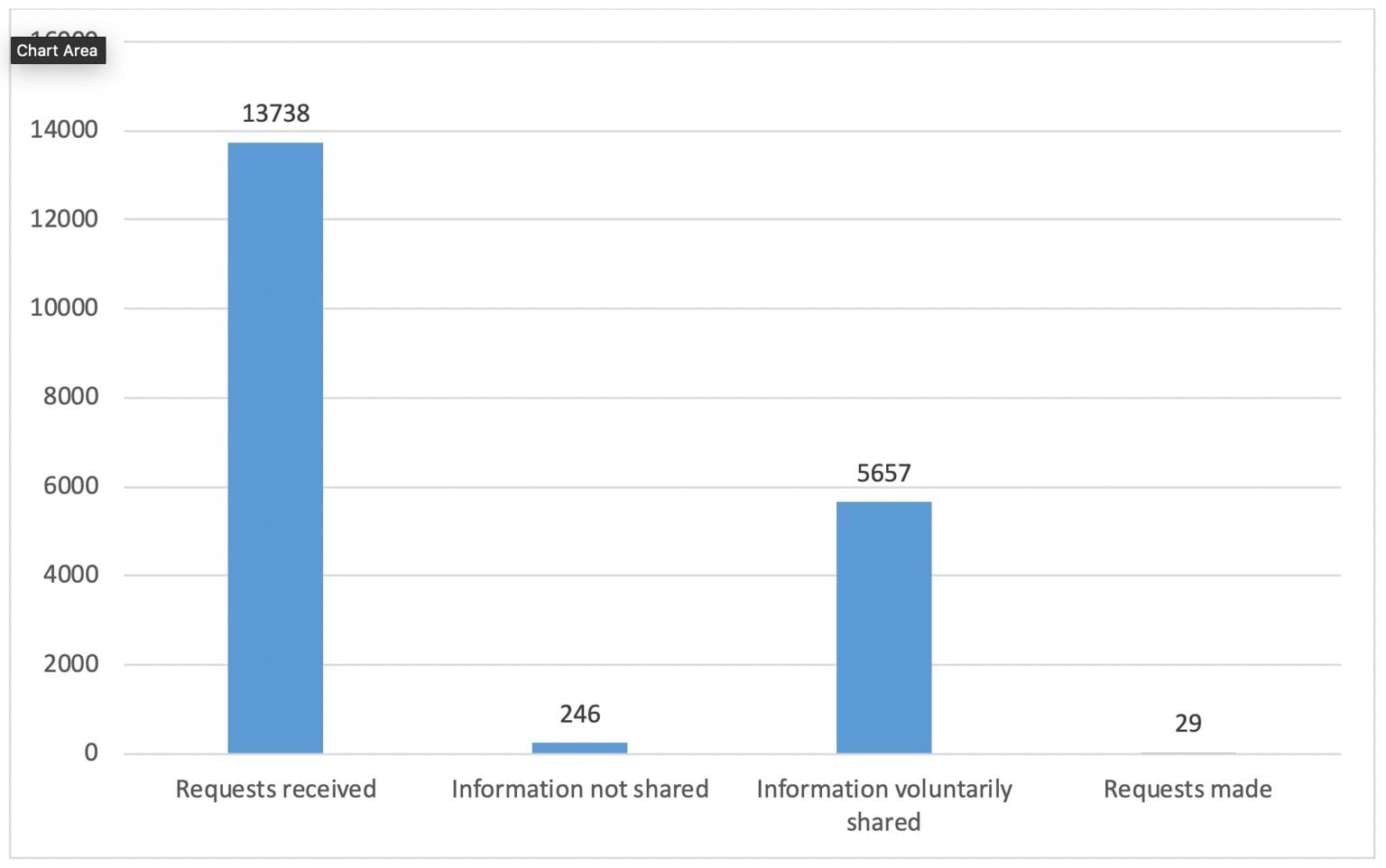

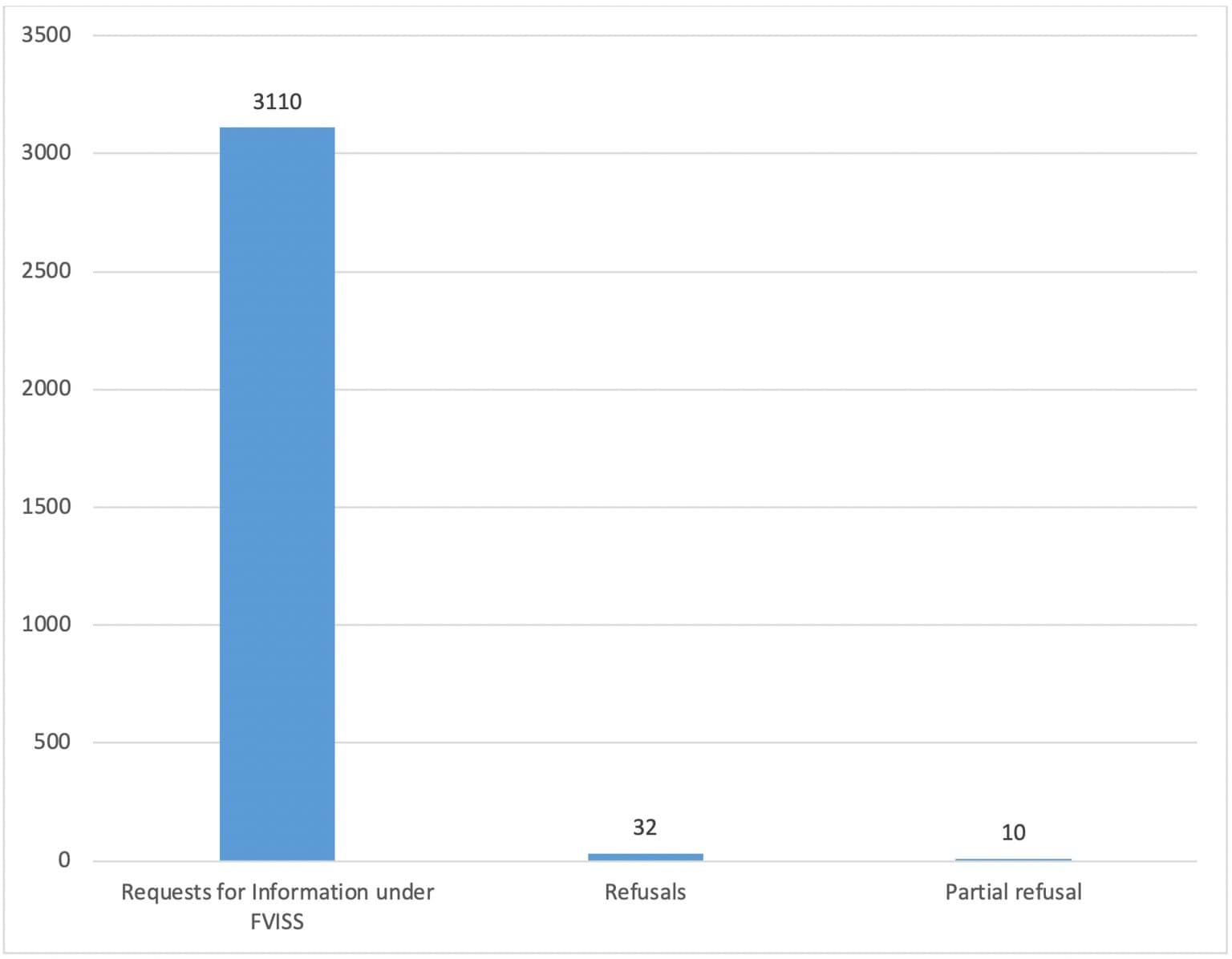

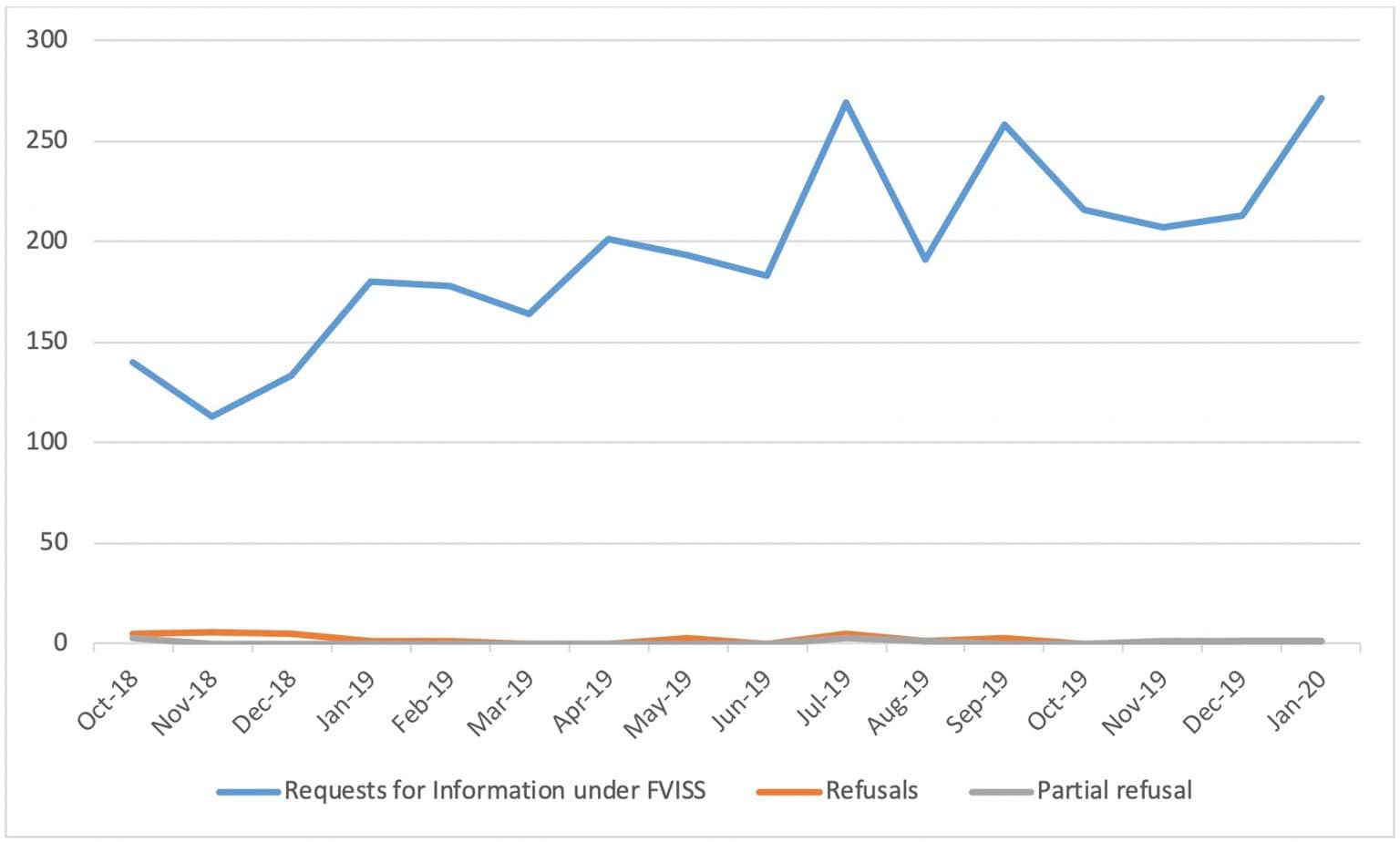

Figure 7: Number of Information Requests Received

Figure 8: Information Not Shared

Figure 9: Information Voluntarily Shared

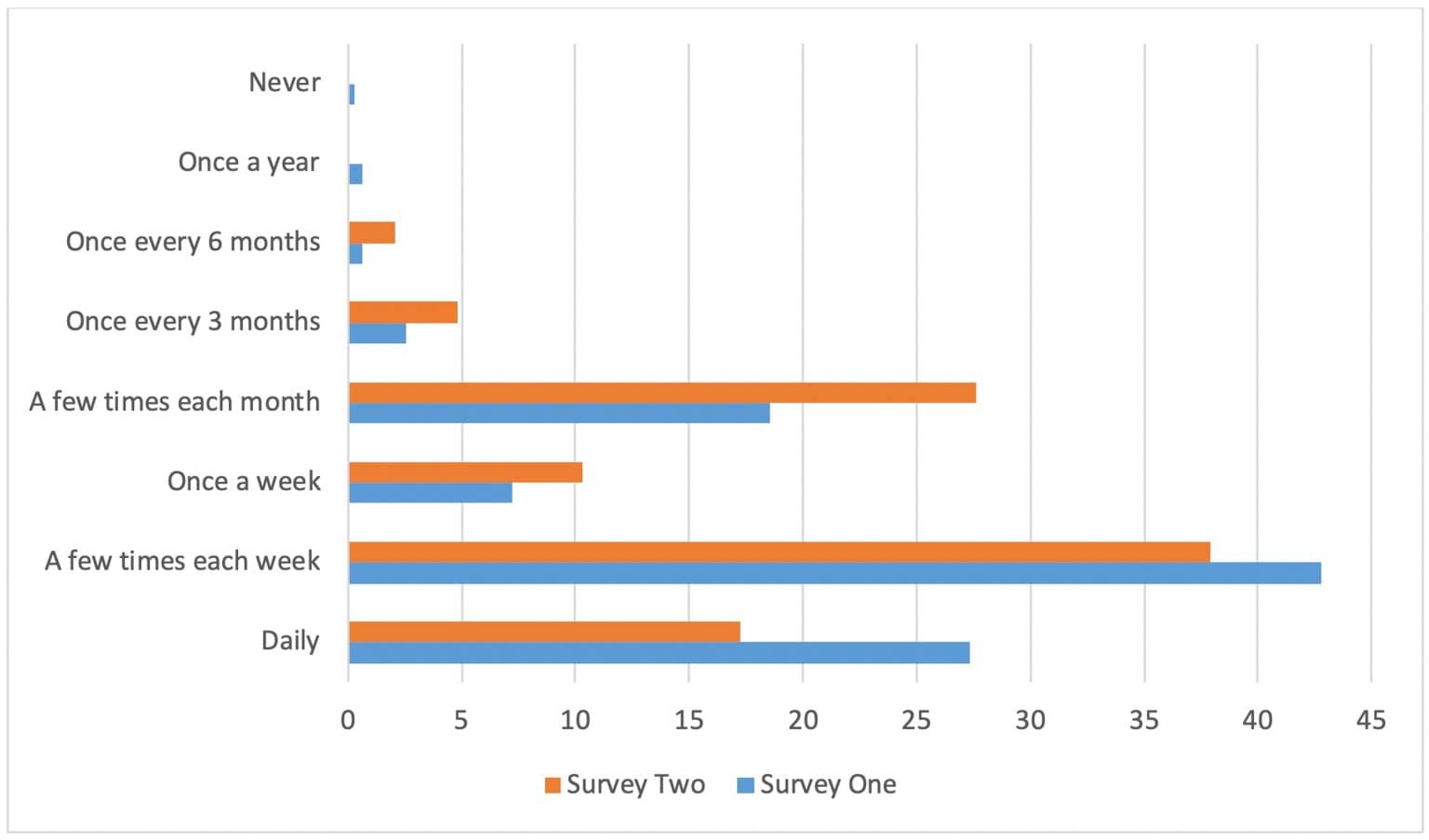

Figure 10: The Percentage of Respondents and their Estimated Frequency of Sharing

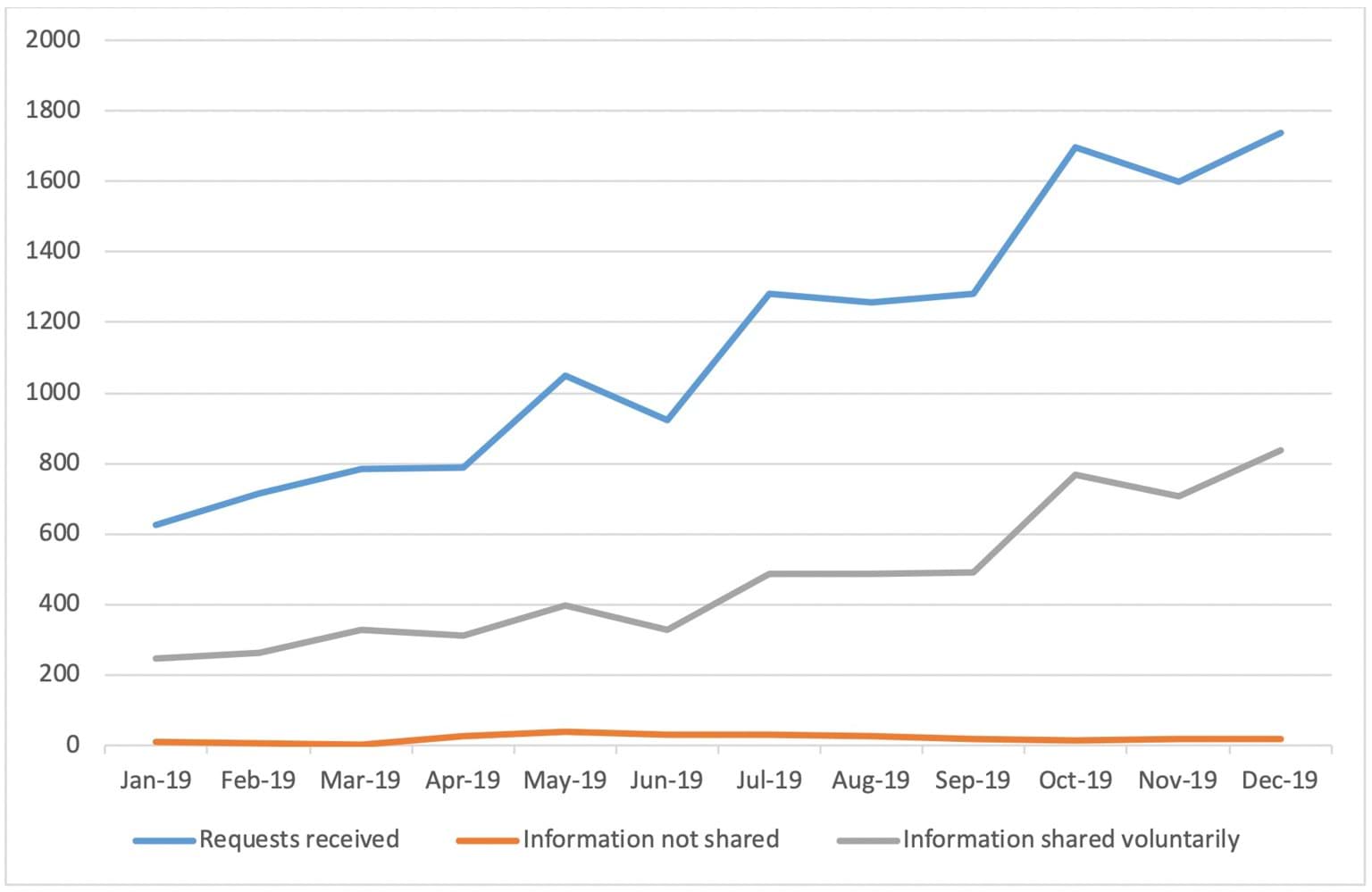

Figure 11: MCV & CCV Information Sharing Activity 2019

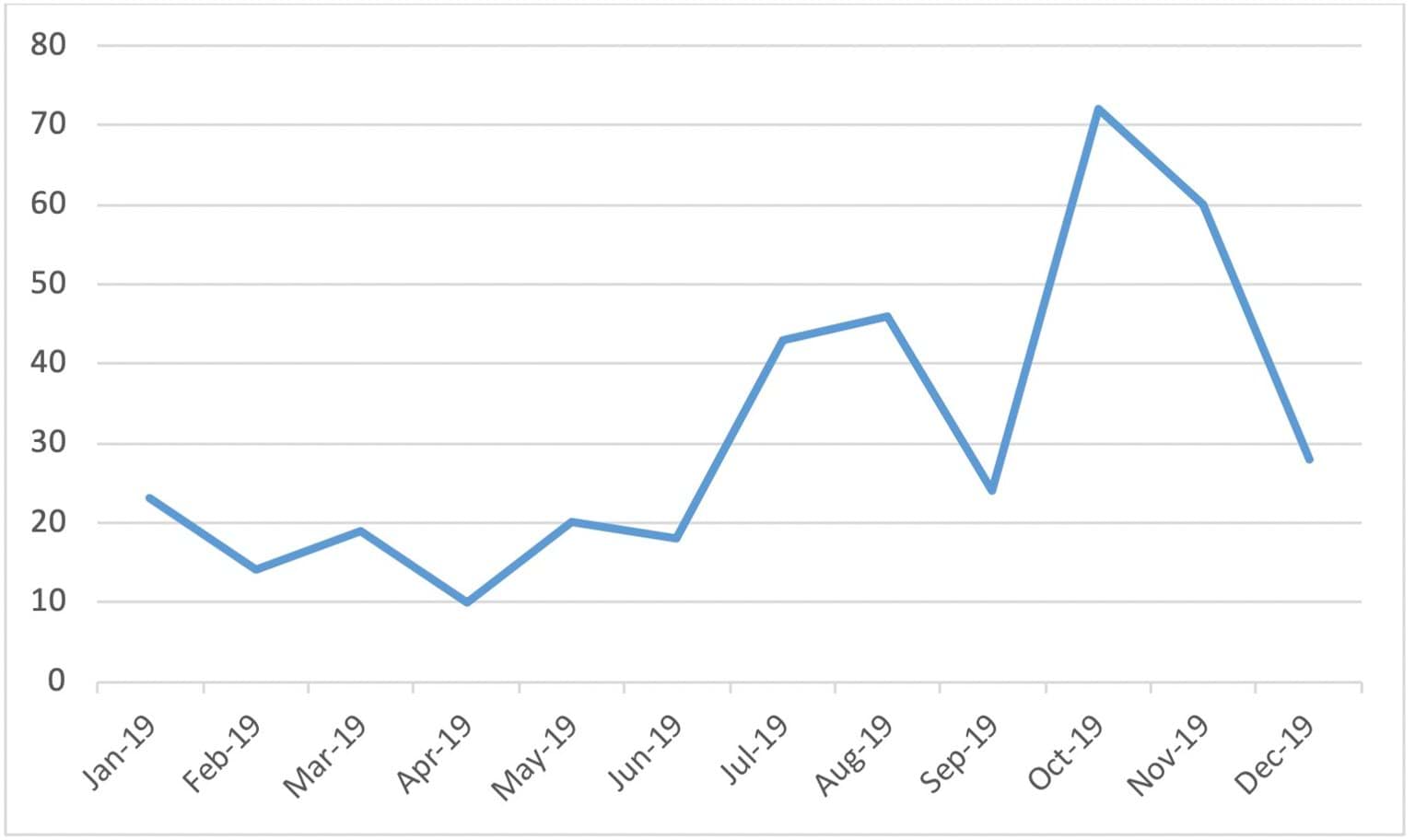

Figure 12: 2019 MCV & CCV Information Sharing Activity by Month

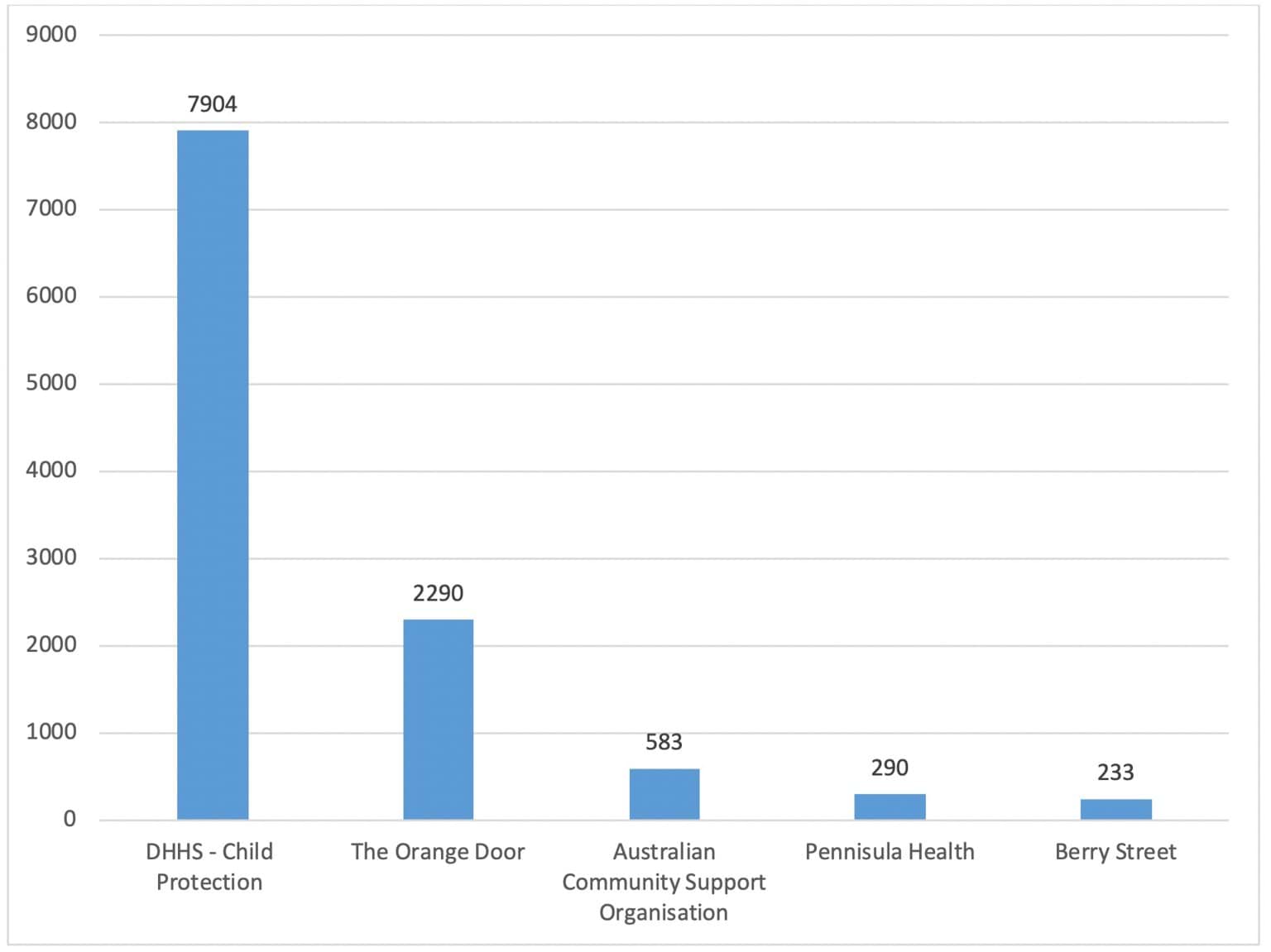

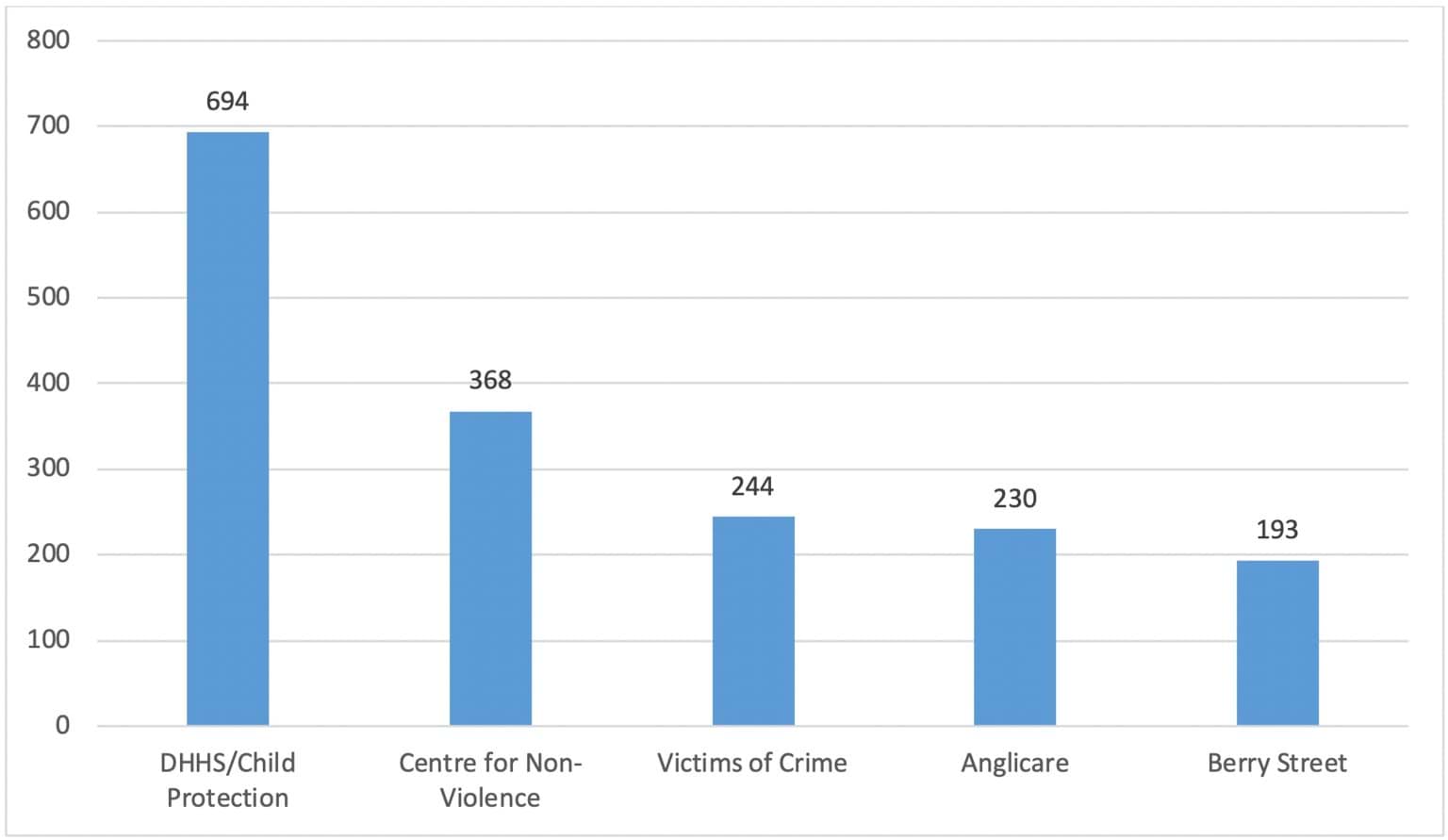

Figure 13: 2019 ISEs that most frequently request information from MCV & CVV

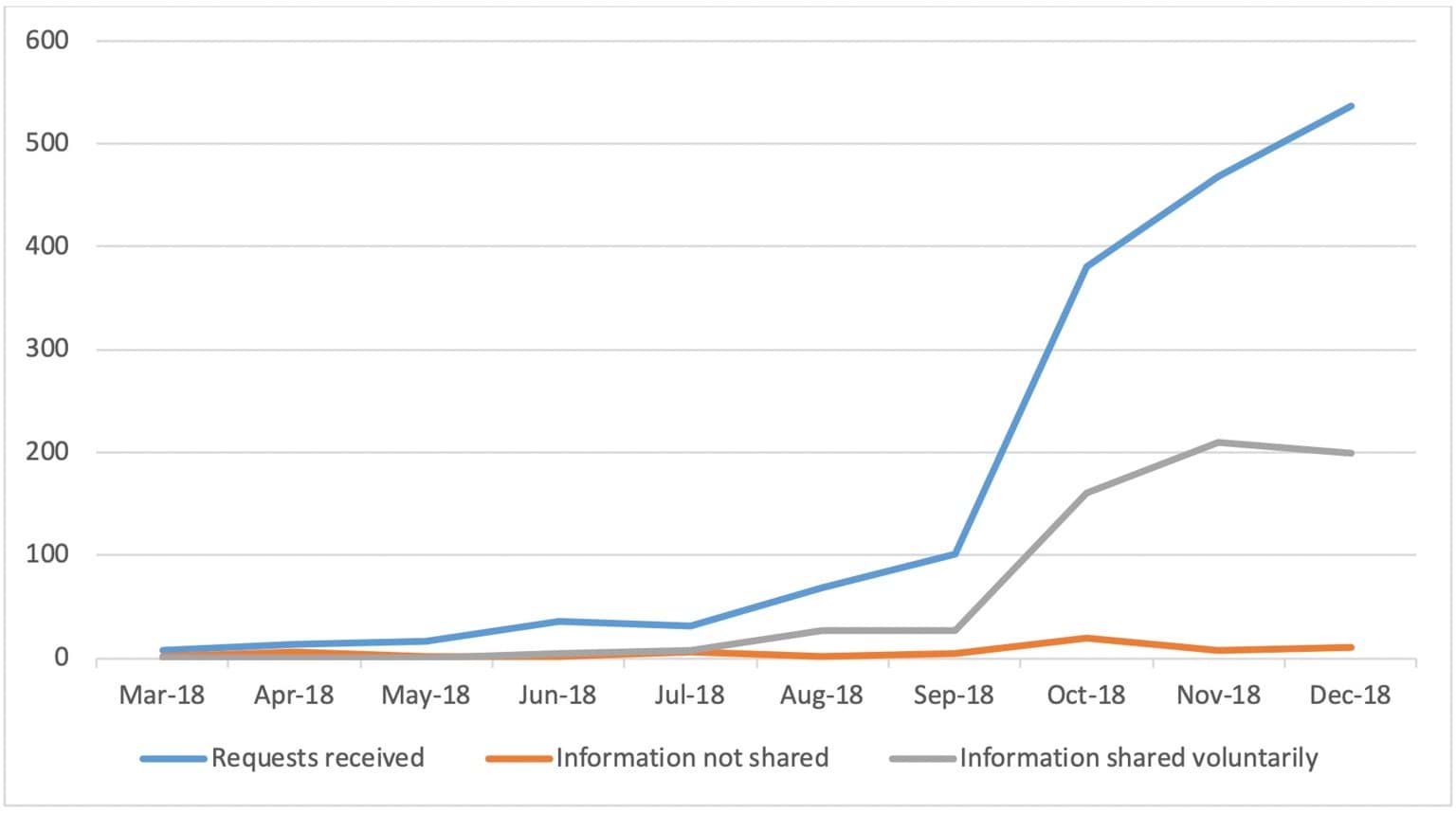

Figure 14: MCV & CCV Information Sharing Activity 2018

Figure 15: 2018 MCV & CCV Information Sharing Activity by Month

Figure 16: 2018 ISEs that most frequently request information from MCV & CVV

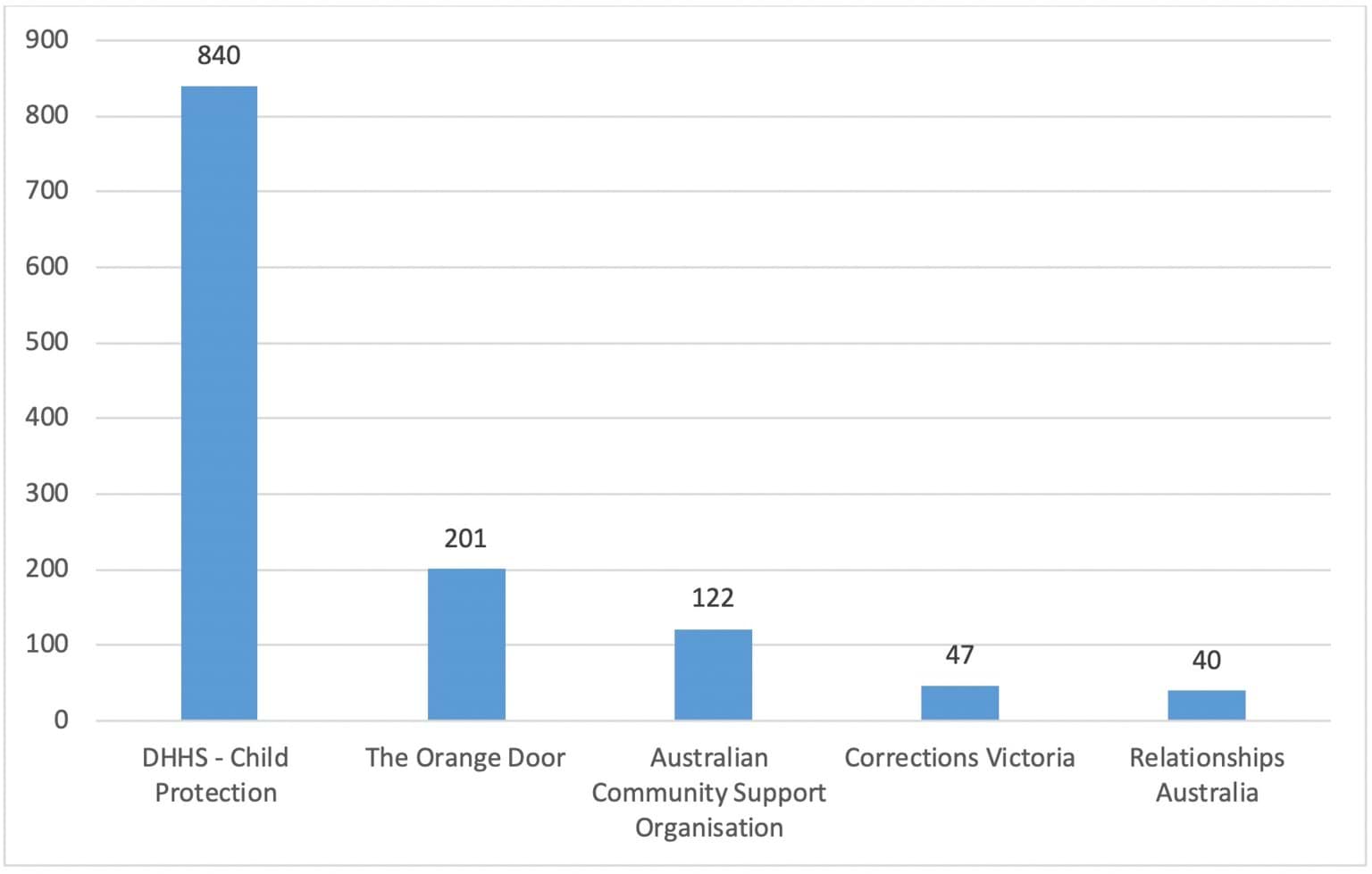

Figure 17: Requests for Information Received by DHHS in 2019

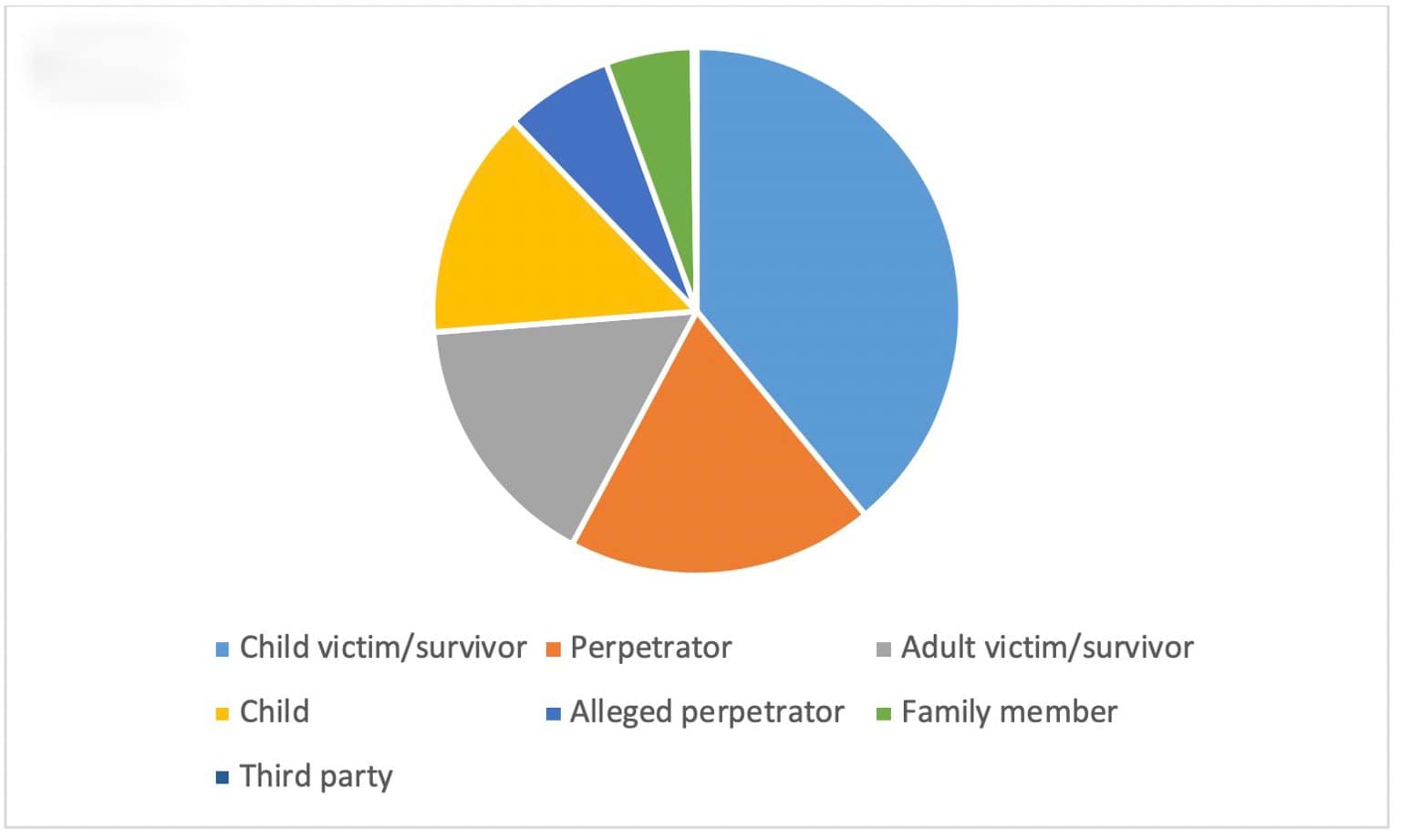

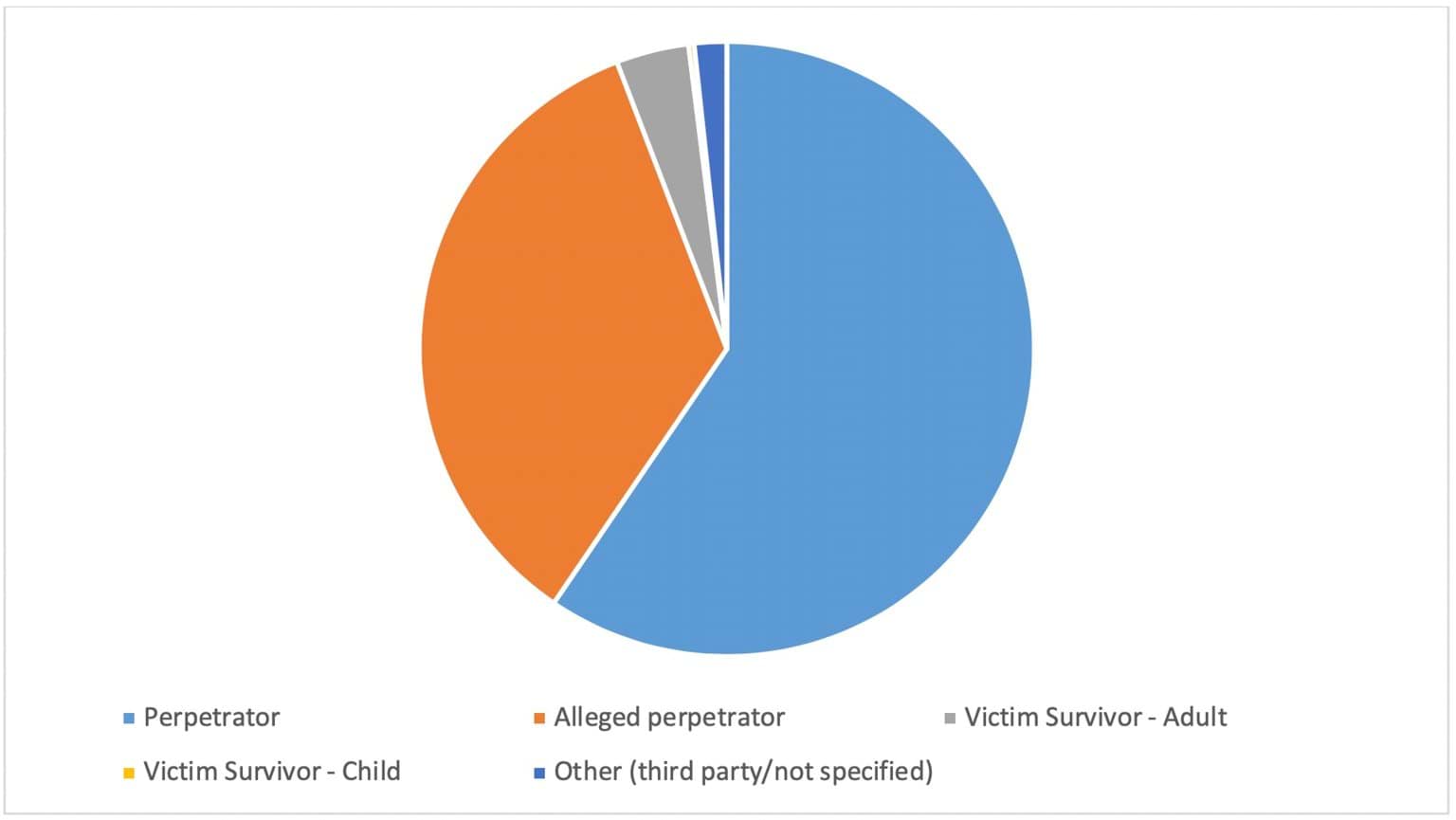

Figure 18: Subject of Information Request Received by DHHS

Figure 19: 2019 ISEs that most frequently request information from DHHS

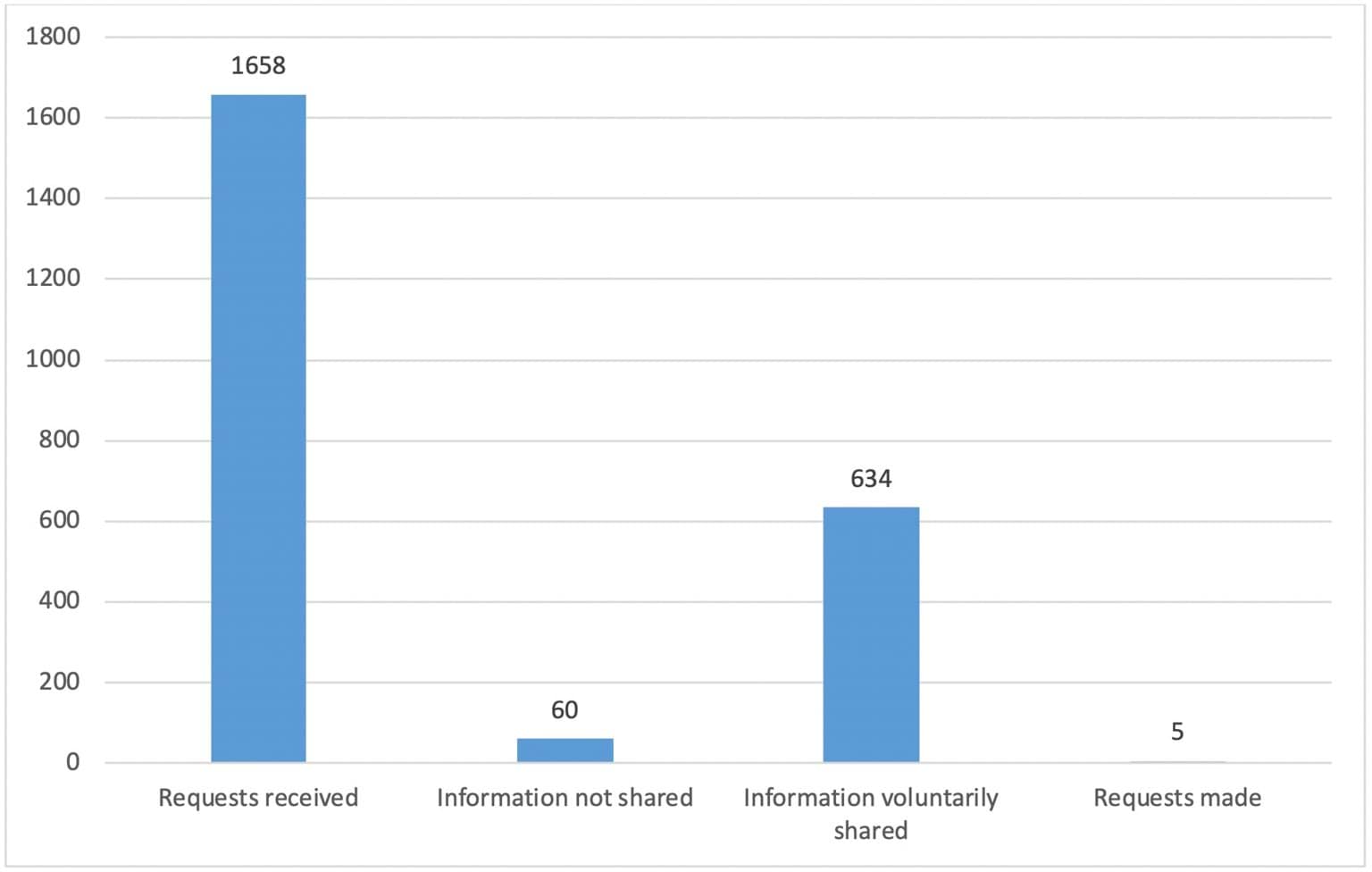

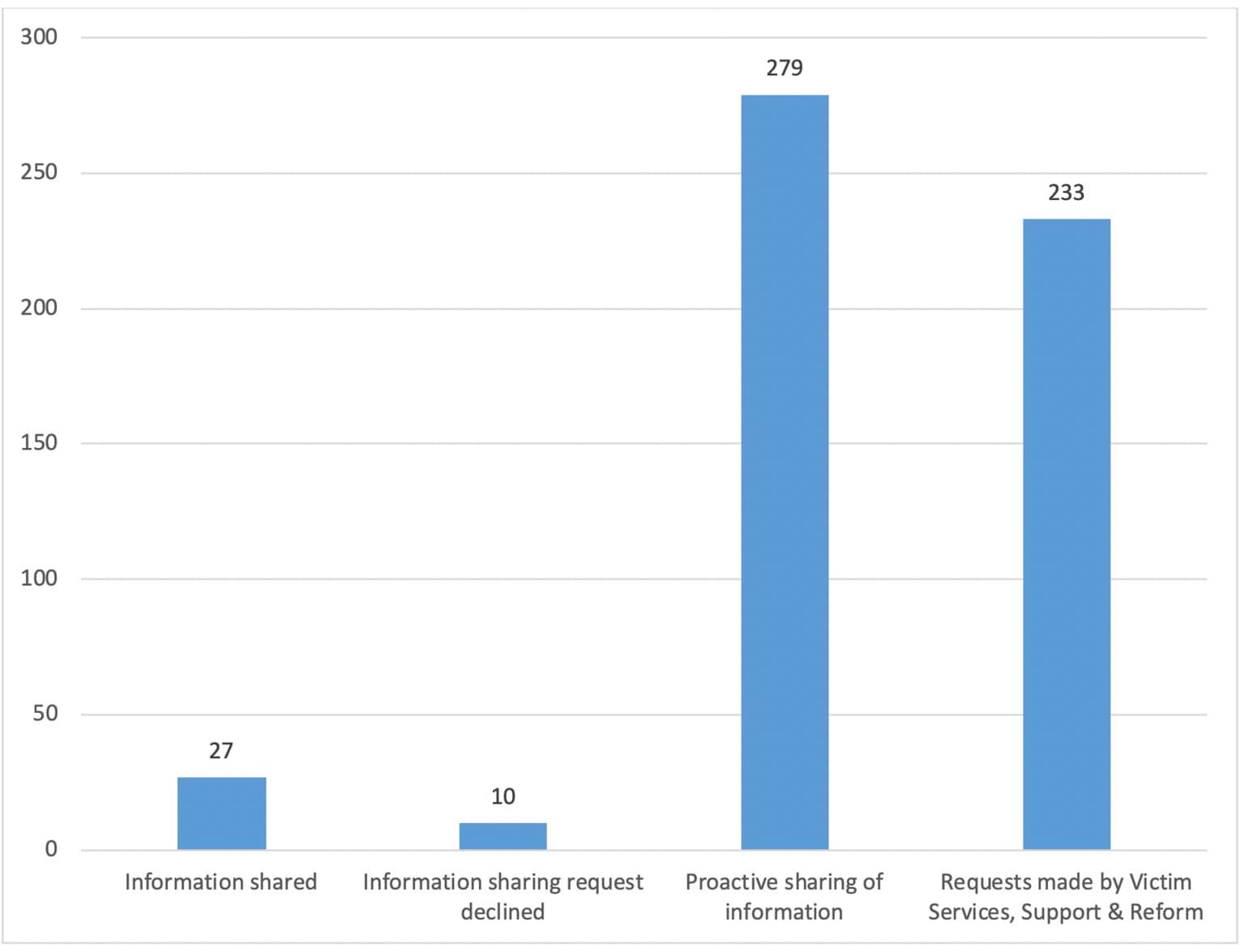

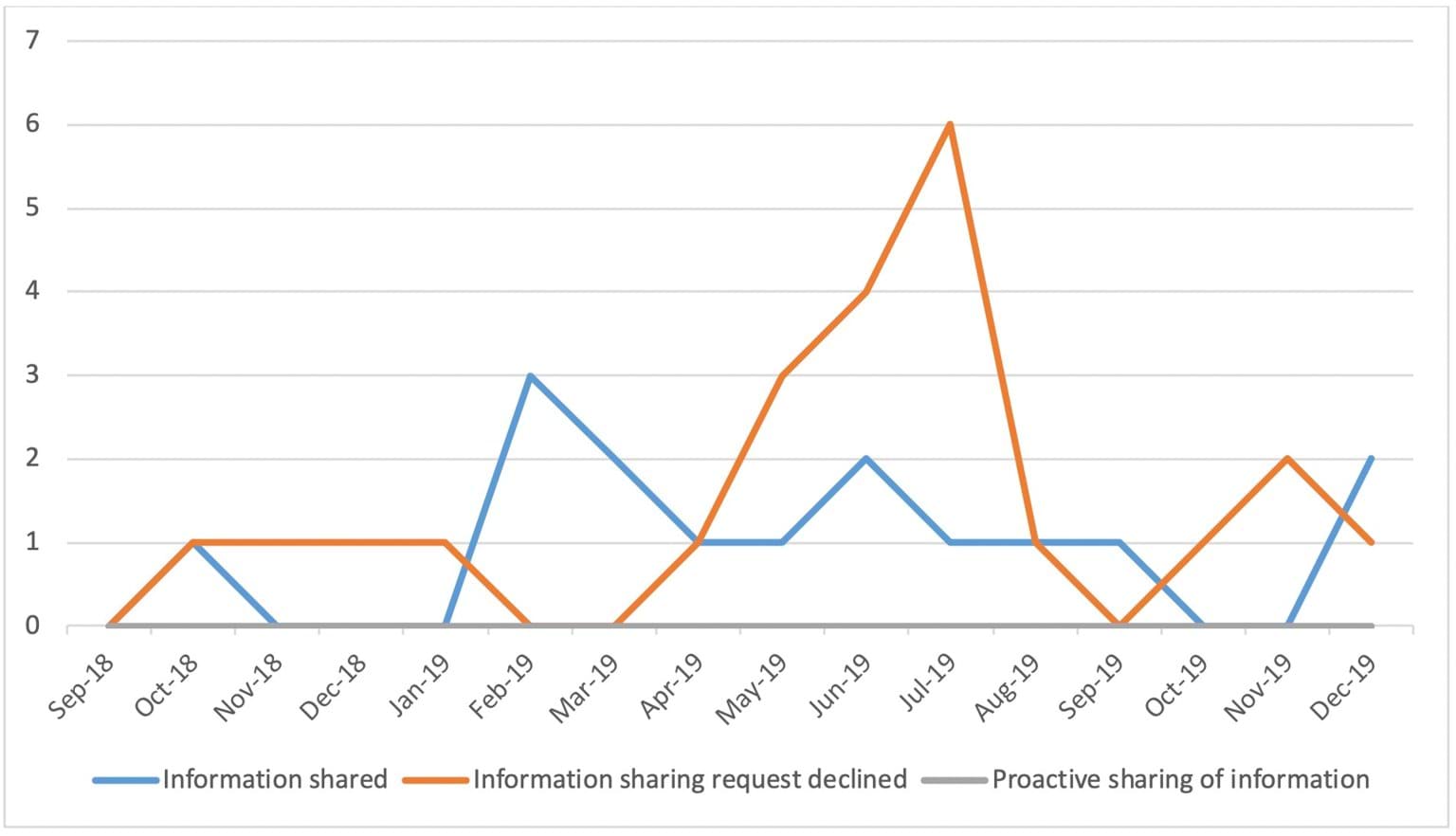

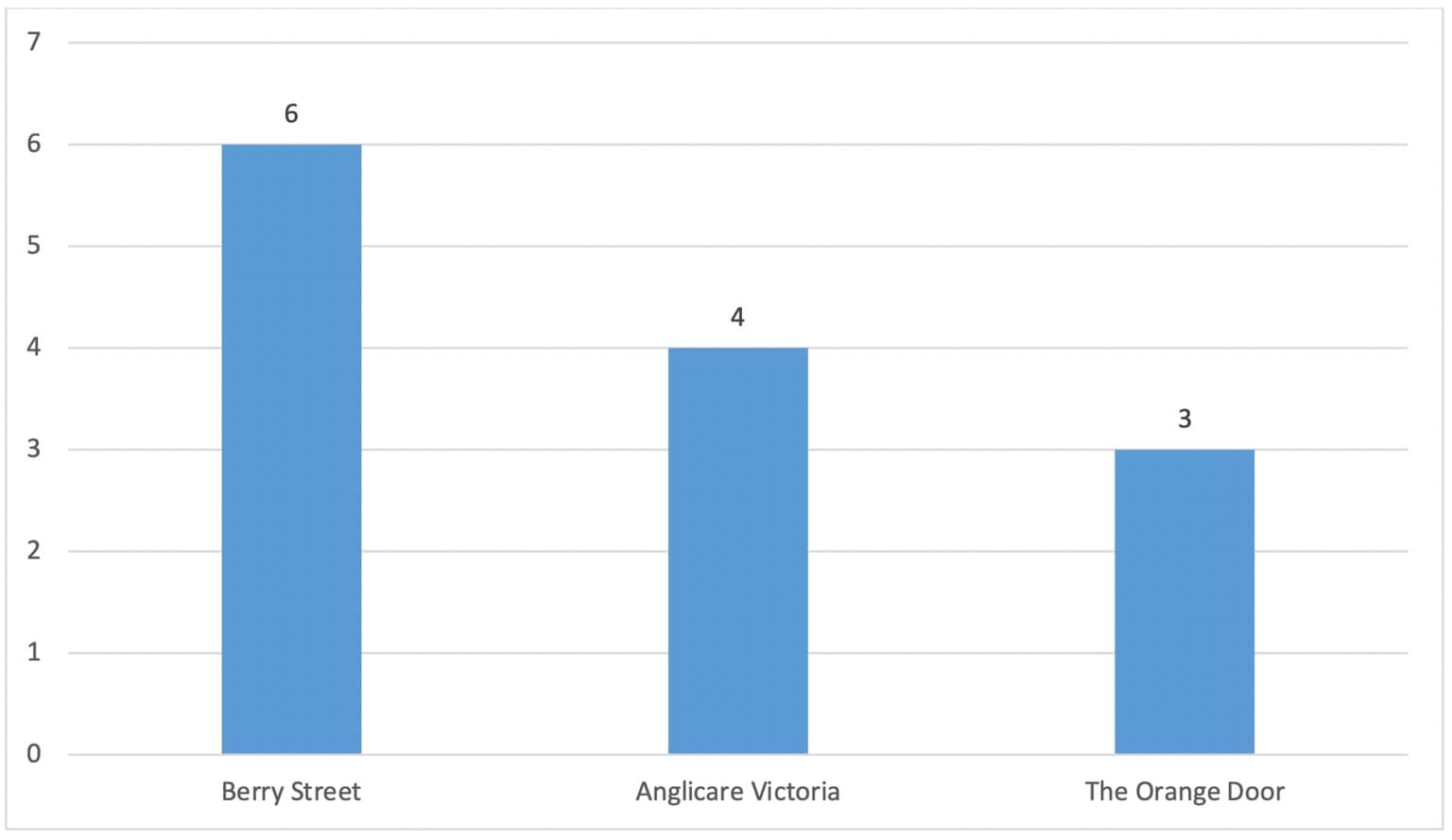

Figure 20: Victim Support Agency Information Sharing Activity, September 2018 - December 2019

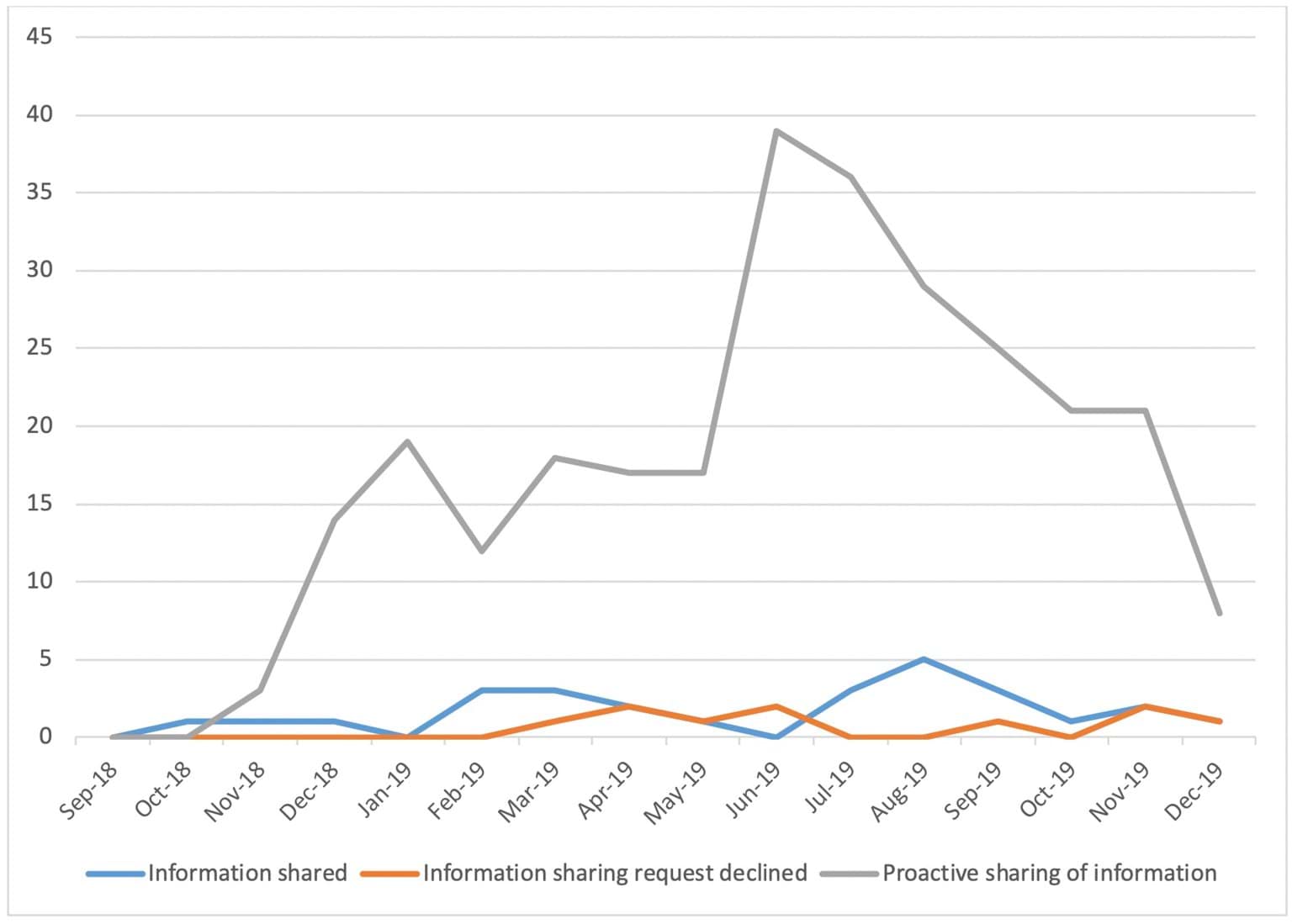

Figure 21: Victim Support Agency Information Sharing Activity by Month

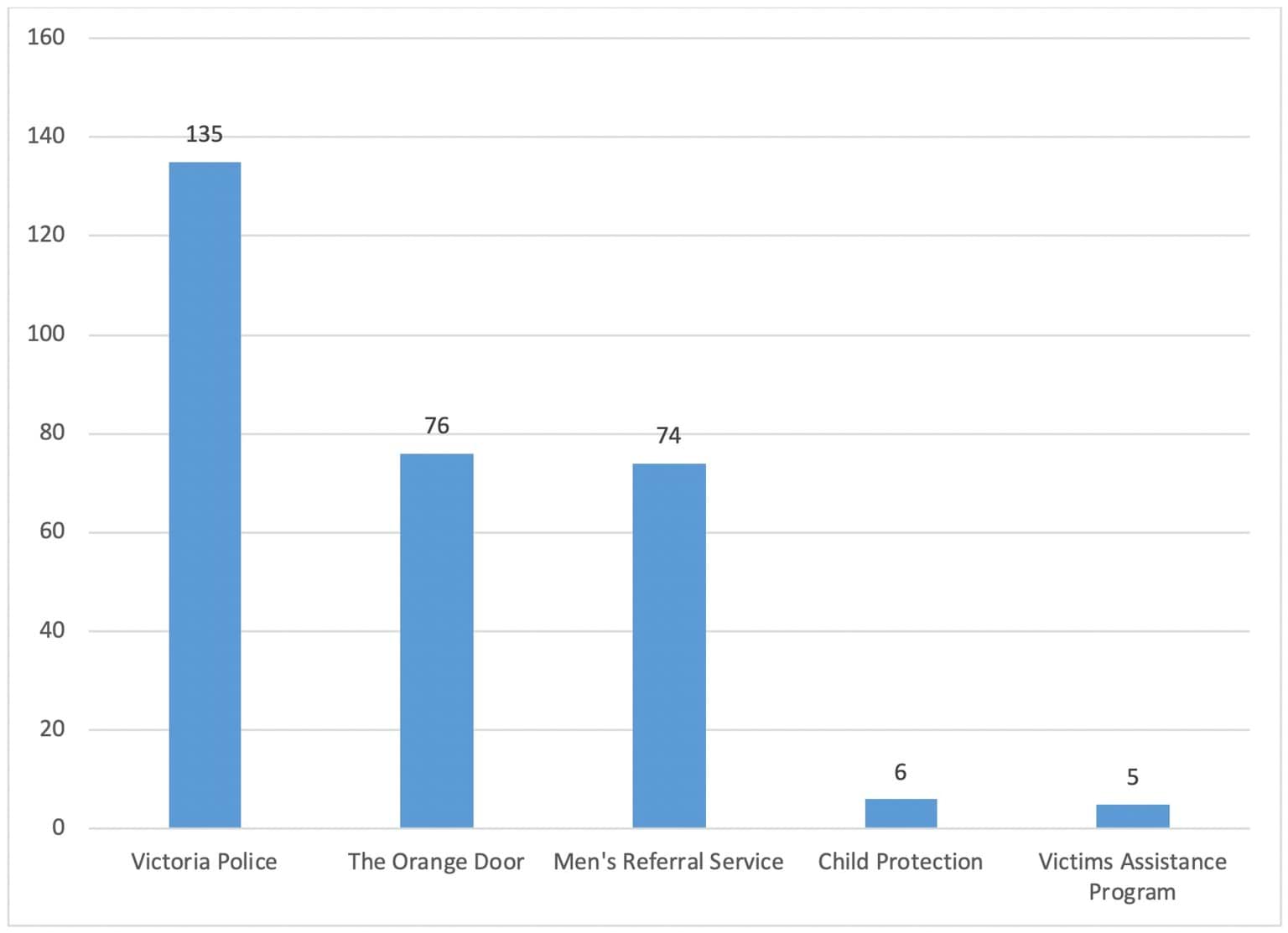

Figure 22: Number of Requests Received by Victim Support Agency

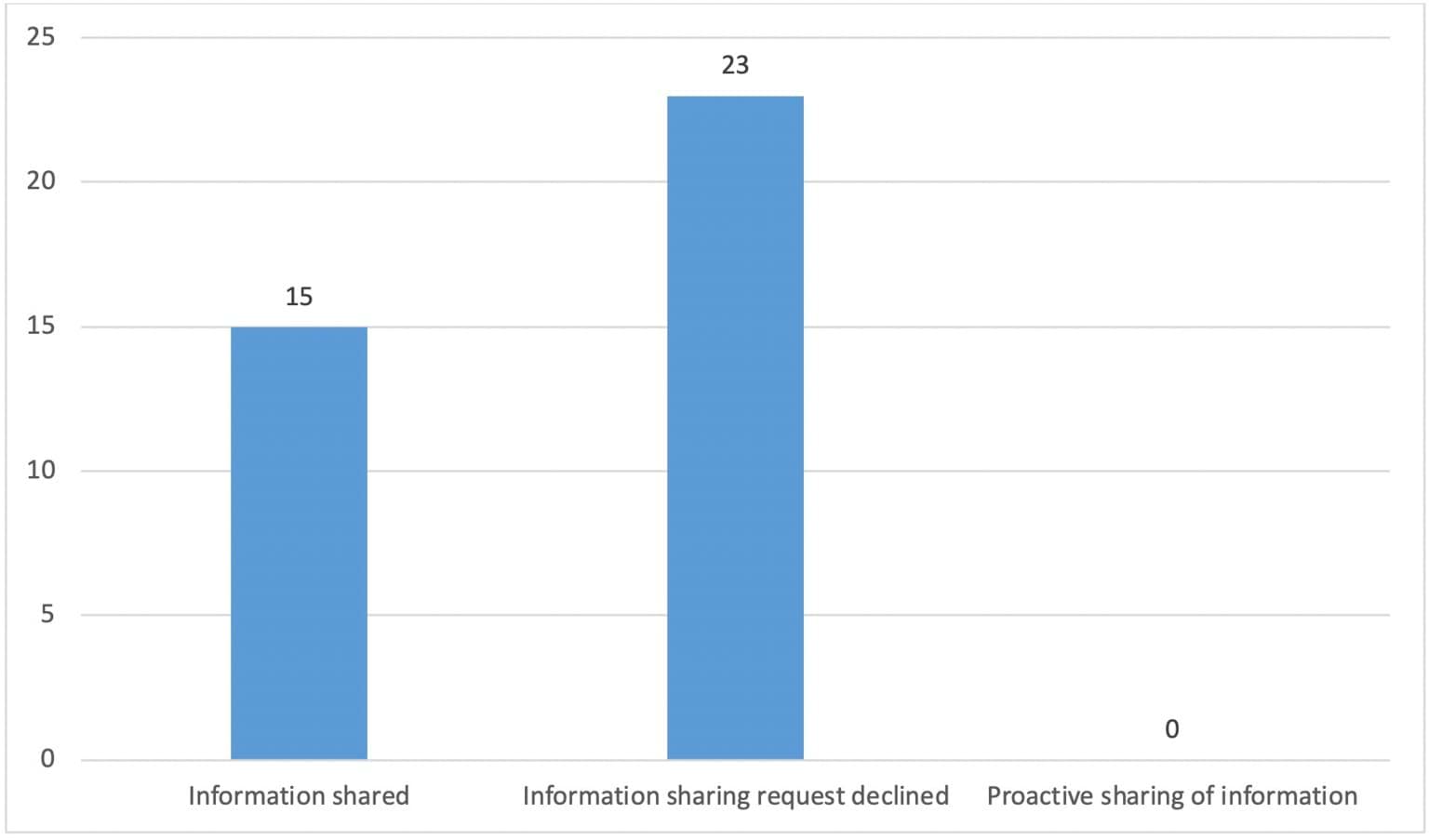

Figure 23: Justice Health Information Sharing Activity 2018-2019

Figure 24: Justice Health Information Sharing Activity by Month

Figure 25: ISEs that most frequently request information from Justice Health

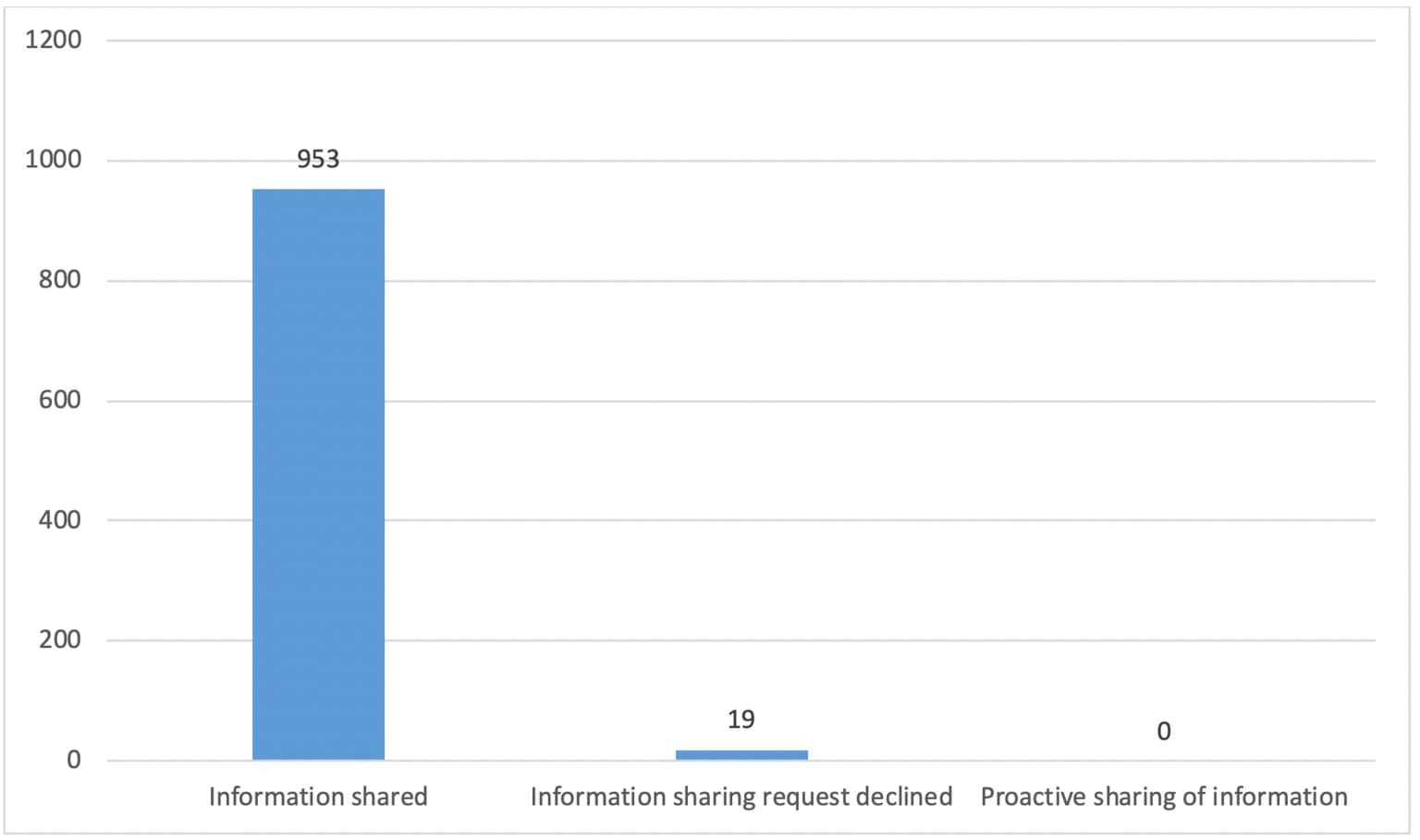

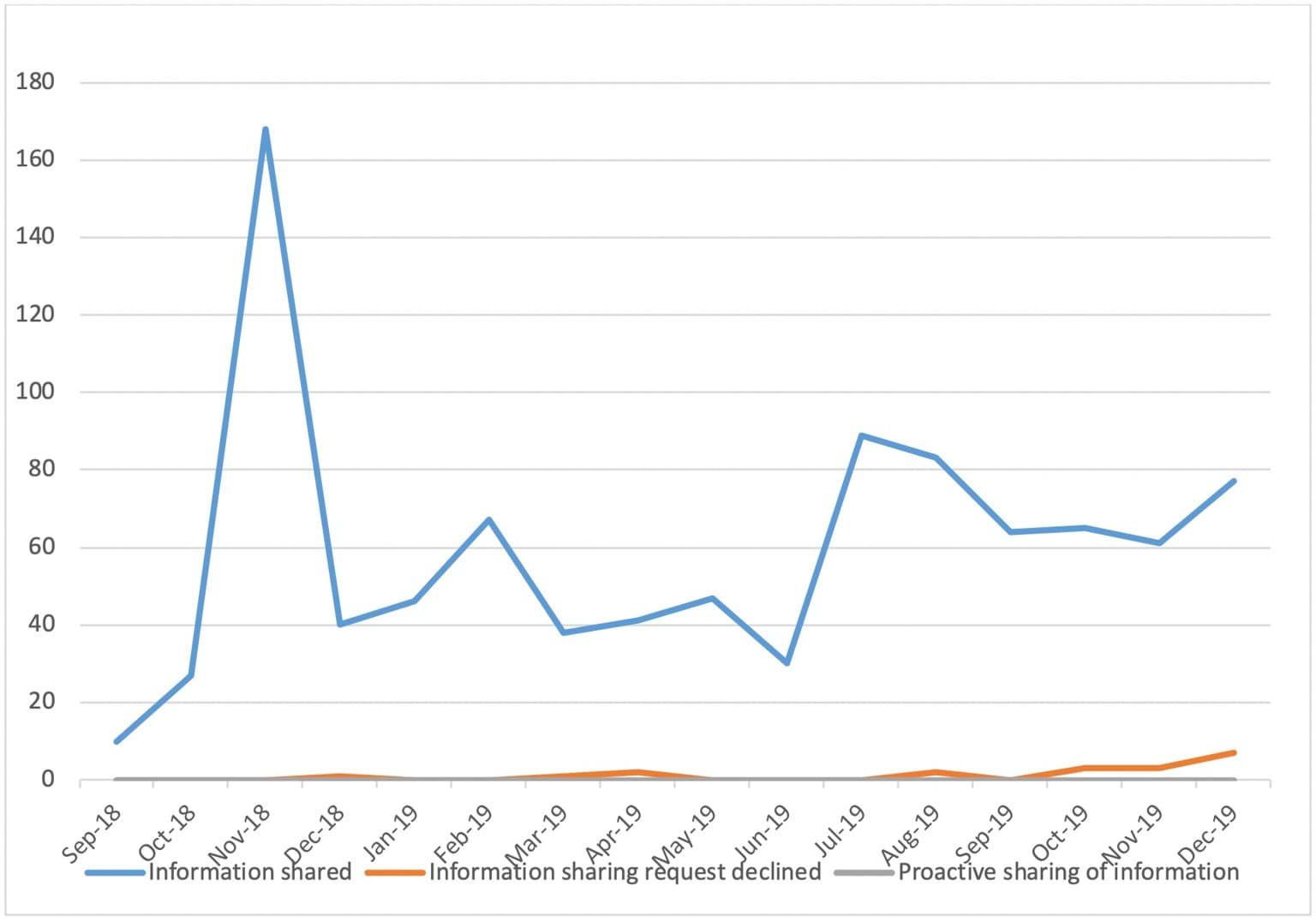

Figure 26: Corrections Victoria Information Sharing Activity, September 2018 - December 2019

Figure 27: Corrections Victoria Information Sharing Activity by Month

Figure 28: Victoria Police Information Sharing Activity, October 2018 - January 2020

Figure 29: Victoria Police Information Sharing Activity by Month

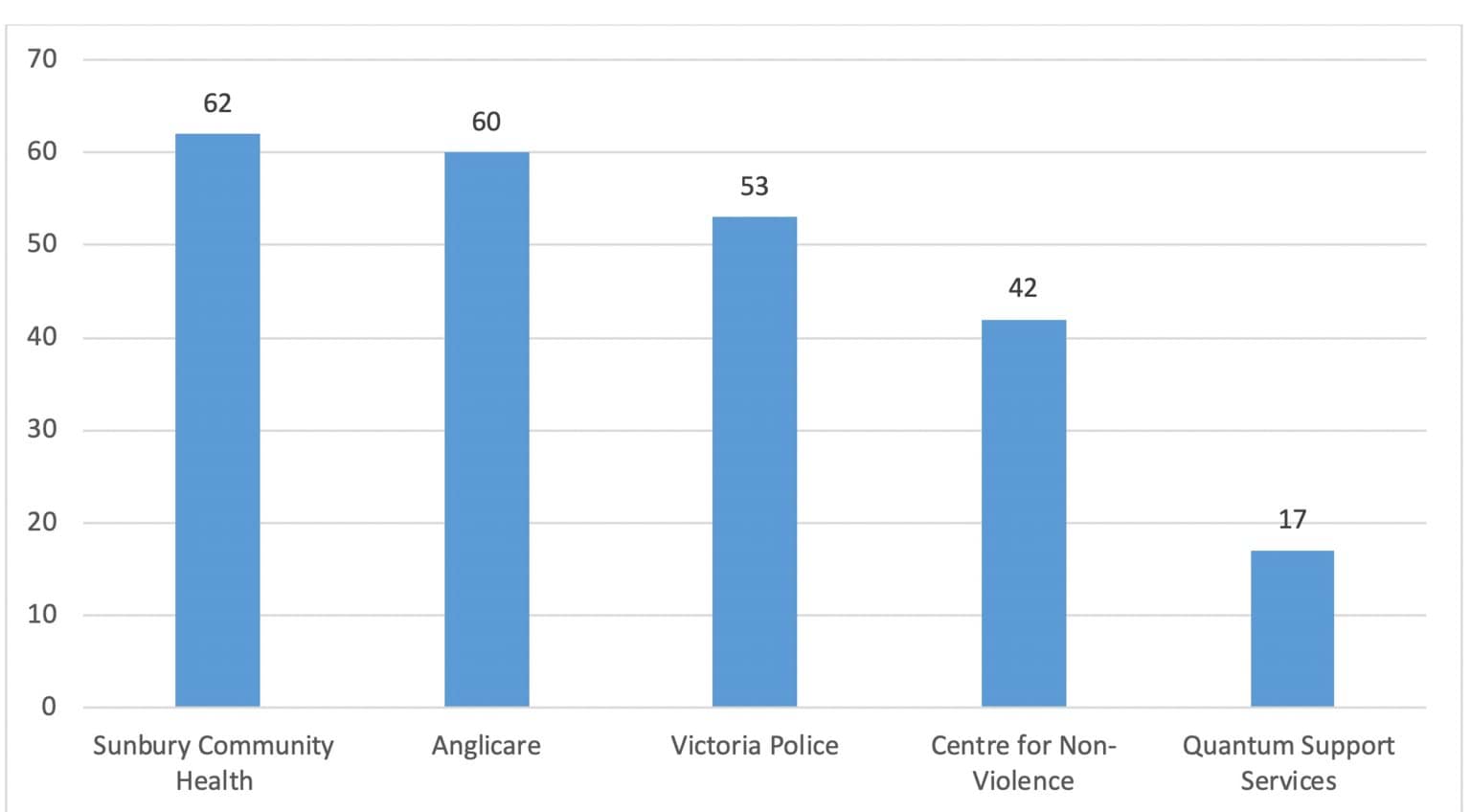

Figure 30: ISEs that most frequently request information from Victoria Police

Figure 31: Subject of Information Requests made to Victoria Police

Note on language

The preamble to the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 [Vic] states that ‘while anyone can be a victim or perpetrator of family violence, family violence is predominantly committed by men against women, children and other vulnerable persons’. Consistent with this, the Royal Commission into Family Violence (RCFV) notes that ‘the significant majority of perpetrators are men and the significant majority of victims are women and their children’ (2016 Summary and Recommendations: 7). While recognising that men may also be victim/survivors of family violence, consistent with the gendered nature of family violence, we employ gendered language throughout the Report.

The Review included women who had experienced family violence as participants. Throughout the Report, we refer to those who have experienced family violence as victim/survivors. Our intention is to recognise women’s experiences of family violence and the harms caused and their work to secure their own safety and that of their children.

Executive summary

Executive summary of the Review of the Family Violence Information Sharing Legislative Scheme Final Report.

The Victorian Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS - the Scheme) was established under Part 5A of the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 as part of the Royal Commission into Family Violence (State of Victoria 2016) reforms. The Scheme aims to:

- better identify, assess and manage the risks to adult and child victim/survivor safety, preventing and reducing the risk of harm; and

- better keep perpetrators in view and enhance perpetrator accountability

The Scheme commenced on February 26, 2018. It was rolled out to Initial Tranche and Phase One organisations, in February and September 2018 respectively. Organisations prescribed to share under the Scheme are known as Information Sharing Entities (ISE). Phase Two is due to commence in the first half of 2021. To date approximately 38,000 workers have been prescribed under the Scheme. In Phase Two approximately 370,000 additional workers are due to be prescribed.

An independent Review of the FVISS is legislatively mandated to ensure that it meets its aims and avoids adverse outcomes. The recommendations and insights of this Review aim to improve the operation of the Scheme generally and the Scheme’s implementation in Phase Two organisations in particular.

The Review was guided by seven questions.

- Has the Scheme been implemented effectively to date?

- Has the Scheme been implemented as intended to date?

- Has the implementation of the Scheme had any adverse organisational impacts?

- What were the key barriers and enablers for implementation?

- Has the Scheme resulted in increased levels of relevant information sharing between prescribed agencies?

- Has the Scheme led to improved outcomes for victim/survivors and increased the extent to which perpetrators are in view?

- Has the Scheme had any adverse impacts?

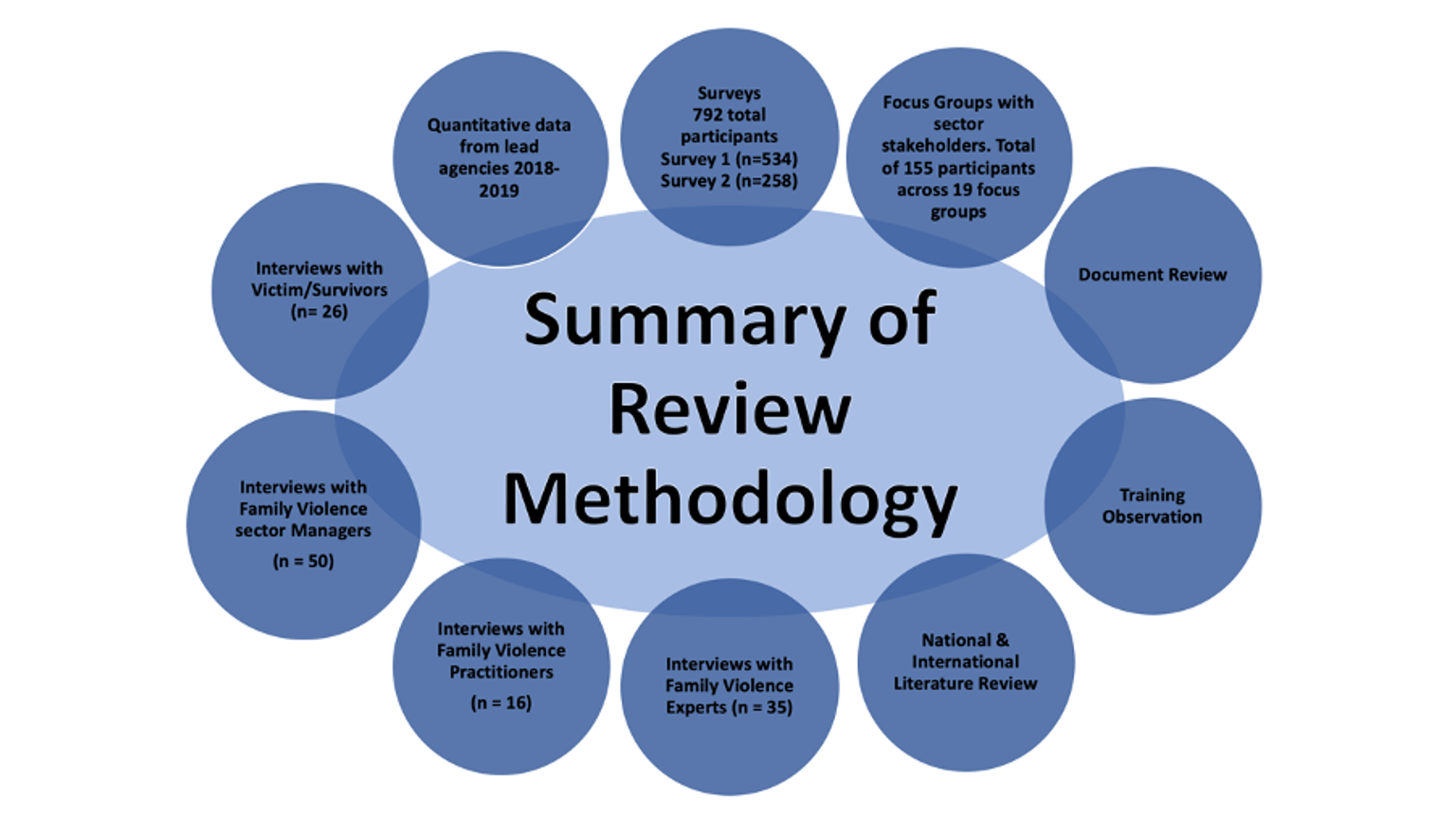

The Review research involved a multi methods approach including empirical research, document review, training observation and a comprehensive literature review. Quantitative data was gathered through two surveys and from lead agencies. Focus groups and interviews were the main source of qualitative data. There were more than one thousand participants in the Review over two data collection periods. Two hundred stakeholders were interviewed or took part in focus groups and 792 people responded to the survey. Participants included women who had experienced family violence, Initial Tranche and Phase One practitioners and managers and family violence experts.

The following approach has been taken to analysing the data.

- The data from all sources is integrated and triangulated.

- Quotes are used extensively throughout and have been drawn from the second period of data collection, with the exception of quotes from victim/survivor participants.

- Where there are contradictory or diverse perspectives and experiences these are noted.

- There is attention paid to continuities, changes and trends.

- Data is de-identified.

- Case studies and examples are used, where appropriate, throughout.

- Victim/survivors’ ‘voices’ are considered central and are included separately at the beginning of the findings section.

- The views of Aboriginal organisations are set out separately in order to acknowledge the continuing legacy of colonialism and the particular issues this raises in relation to the Scheme.

Findings and recommendations

Impacts and outcomes of the Scheme for women who have experienced family violence

Twenty-six women who had experienced family violence and interacted with services participated in the Review. Most recognised the value of information sharing in facilitating referrals, accurately assessing their risk, reducing the number of times they had to tell their stories, and in facilitating a helpful response to their reports of family violence. However, family violence information for these women was also their security. They were worried about the misinterpretation or misuse of information, and the lack of information shared about perpetrators. The women were concerned about the approaches of Child Protection to information sharing, as they felt blamed for the difficulties of their post-separation lives. There was fear amongst mothers that the disclosure of family violence combined with information sharing could expose them to negative judgements and potentially the loss of their children.

Recommendation 1Privacy policy updates related to family violence information sharing are in development or have been developed by all relevant sectors in the Initial Tranche and Phase One. Phase Two sectors and organisations should update privacy policies to address family violence information sharing prior to prescription. Organisations should be encouraged to communicate these policies to victim/survivors to ensure they are informed about relevant privacy protections. |

Impacts and outcomes of the Scheme for Aboriginal people

Aboriginal organisations had very specific concerns about the FVISS based on the historical and ongoing experience of state intervention in Aboriginal lives, especially child removal. It is recognised that structural disadvantage experienced by Aboriginal people contributes to the over representation of Aboriginal children and families in notifications to Child Protection and consequent outcomes. There have been a number of initiatives legislated in the Children, Youth and Families Act 2005 to enhance outcomes, including the implementation of the Aboriginal Child Placement Principle (s.13) and provisions for Aboriginal agencies to take full responsibility for Aboriginal children on protection orders (s.18). Yet, there was still wide spread concern that the FVISS in combination with the Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS) could lead to an increase in the involvement of Child Protection in Aboriginal mothers’ lives. Some participants valued the opportunity the Scheme for greater shared attention to children’s risk and more collaborative relationships between child and family welfare agencies and specialist family violence services. Most were concerned the Scheme raised the risk that women experiencing family violence would avoid or disengage from services to maintain their privacy, autonomy and, critically, to avoid Child Protection involvement. The Scheme, and family violence reforms generally, have had significant resource implications for Aboriginal organisations dealing with family violence. Family Safety Victoria has put in place strategies to facilitate the inclusion of Aboriginal perspectives on the reforms. Despite some additional resourcing and consultation with Aboriginal organisations, there was a view that cultural safety and competence was not being sufficiently embedded in mainstream services and that Aboriginal perspectives and knowledges were not being sufficiently incorporated into information sharing training.

Recommendation 2Monitoring of the interaction and impacts of the FVISS and the CISS on Aboriginal people, especially mothers experiencing family violence, should be undertaken centrally to produce robust specific datasets of these interactions and outcomes. The development of these datasets is critical to ensure any adverse effects on First Nations peoples and communities are addressed. |

Recommendation 3The strategies that Family Safety Victoria has put in place to ensure that Aboriginal perspectives are included in the FVISS and MARAM (Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management) reforms, including sector grants, working groups, the Dhelk Dja partnership forum, regional coordinators and Aboriginal Practice Leaders at Orange Door sites, should continue to be funded and resourced. |

Recommendation 4In order to ensure best practice support for Aboriginal people experiencing family violence, increased funding should be provided to Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (ACCO) to address existing and emerging service needs associated with family violence reforms generally and the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme in particular. |

Recommendation 5ACCO need more resources to contribute to the development and delivery of training on Family Violence Information Sharing so all training builds cultural safety and competence across all mainstream services in order to better support good outcomes for Aboriginal women and children experiencing family violence. |

Recommendation 6In order to ensure that Aboriginal people receive culturally safe and appropriate services when they disclose family violence the continuing shortage of Aboriginal workers in the family violence sector should be addressed urgently. |

Recommendation 7In consultation with Aboriginal organisations, Family Safety Victoria should ensure that there is an annual forum or other opportunity where key stakeholders consider any adverse impacts of the Scheme on Aboriginal people. This forum or other opportunity should specifically consider the impacts of the Scheme on mothering and any issues related to Child Protection. |

1. Has the Scheme been implemented effectively to date?

These findings relate specifically to the central support that has been provided mainly but not exclusively by FSV. It includes training, Ministerial Guidelines, an Enquiry Line, sector grants and Practice Guidance. There is solid evidence that the Scheme’s implementation has been broadly effective. There are lessons for effective implementation that can be used to improve implementation to Phase Two. The effectiveness of training has been variable, due to the interlinked issues of availability and accessibility, timing and sequencing, quality and communication. The sector grants have been a critical component of effective implementation and will be important to assist the ongoing process of implementation in each phase of the rollout and to support the extra organisational activity produced by the Scheme. The Enquiry Line provides an important support mechanism and should be continued and expanded in anticipation of Phase Two. The Ministerial Guidelines provide a firm foundation for the Scheme’s policy framework. The Practice Guidance now available to organisations is extensive and will assist Phase Two implementation.

Recommendation 8Timing and sequencing issues must be addressed before the prescription of Phase Two organisations in order to allow for the development of quality training content, including quality accompanying materials. Adjustments from piloted training need to be made prior to prescription. Training timelines will need to take into account the limited number of family violence expert trainers. |

Recommendation 9Those engaged to deliver training should be both expert trainers and experts in family violence. A distinct training pipeline for expert family violence trainers will need to be established to serve the training needs of Phase Two. |

Recommendation 10In order to be effective, cross sector training needs to be more oriented towards experiential learning based on best practice adult education strategies, such as case studies and practice specific exercises. |

Recommendation 11All training and training materials need to emphasise the circumstances in which it is appropriate to use either the FVISS or the CISS and that both schemes have the same consent requirements. In particular the Ministerial Guidelines on this issue should be highlighted and practical exercises and case studies should be developed focused on this aspect. |

Recommendation 12In the prescription of Phase Two organisations, Family Safety Victoria and other relevant departments should communicate the training strategy, plan, content and timing clearly and well in advance of the scheduled training. |

Recommendation 13Consideration should be given to extending the operating hours of the telephone aspect of the Enquiry Line to business hours. Where there is the need for expert legal advice, an appropriate referral to obtain such advice should be provided to the enquiring organisation, where that organisation does not otherwise have ready access to such advice. The Enquiry Line should be fully resourced for at least two years after the prescription of Phase Two organisations. |

Recommendation 14The on-line list of ISEs should be completed and made available to all ISEs prior to the prescription of Phase Two. |

Recommendation 15The sector grants need to be continued for the Initial Tranche and Phase One organisations until at least June 2023 to continue the process of embedding the Scheme. These grants will be critical for Phase Two. The level of these grants should recognise the scale of the organisational work and cultural change required, particularly for organisations that have not previously been directly engaged in family violence work. |

2. Has the Scheme been implemented as intended to date?

Some elements of the Scheme have been implemented as intended, while others have not. The major divergence between initial plans for implementation and the actual implementation relate to the substantial delay in the delivery of critical components of the MARAM (Multi Agency Risk Assessment and Management). The prescription of the Initial Tranche and Phase One were both slightly delayed. The original timelines were ambitious, and these slight delays are not considered a major issue. The CISS was implemented in September 2018 and aligned with the FVISS. The implementation of the CISS in conjunction with the FVISS was not initially contemplated. The dual implementation has made the implementation of FVISS more complex and time consuming. In the Initial Tranche, training was provided to less workers prior to prescription than originally contemplated and no training was available to Phase One workers prior to prescription. By the end of 2019 the majority of Phase One workers had not received training in the FVISS or MARAM.

The physical distancing requirements of COVID-19 may impact on training of Phase Two workers. These impacts cannot be predicted with any certainty at time of writing. The recommendations with regard to Phase Two training should be read taking into account the uncertain impact of COVID-19.

Recommendation 16Timing and sequencing for Phase Two needs to ensure the training of a sufficient number of Phase Two workers prior to prescription. |

Recommendation 17Consideration should be given to how the perpetrator aspect of risk assessment will be incorporated into Phase Two training. The sequencing and timing of the implementation of Phase Two, particularly in relation to the perpetrator aspects of MARAM, and the rationale for this, should be communicated clearly to key stakeholders. |

3. Has the implementation of the Scheme had any adverse organisational impacts?

The benefits of the Scheme were widely understood to be significant. However, the Scheme has created additional workload for organisations. Although most participants highlighted an additional workload to implement the Scheme, each organisation had different views on the extent of ongoing additional work it was creating. The early implementation stages created extra work related to attending training, creating new policies and procedures and in many cases, tailoring templates to suit specific workplaces or sectors. For many organisations, there is ongoing additional workload, depending on the volume of requests being made and received and the extent to which this exceeded previous sharing practices. Overall however, participants felt the additional workload was worth the benefit of receiving more thorough and accurate information for family violence risk assessments and management. For non-specialist organisations in particular, the heightened awareness of and training about family violence that has accompanied the introduction of the Scheme has provided the impetus for some staff in those organisations to disclose, often for the first time, their own historical or ongoing experiences of family violence. These disclosures, which may be made in the workplace, highlight the need for such organisations to have policies in place that address staff related family violence issues.

Recommendation 18Prior to the implementation of Phase Two, resources and policies should be in place in all prescribed and all soon to be prescribed organisations to support workers who disclose family violence. |

4. What were the key barriers and enablers for implementation?

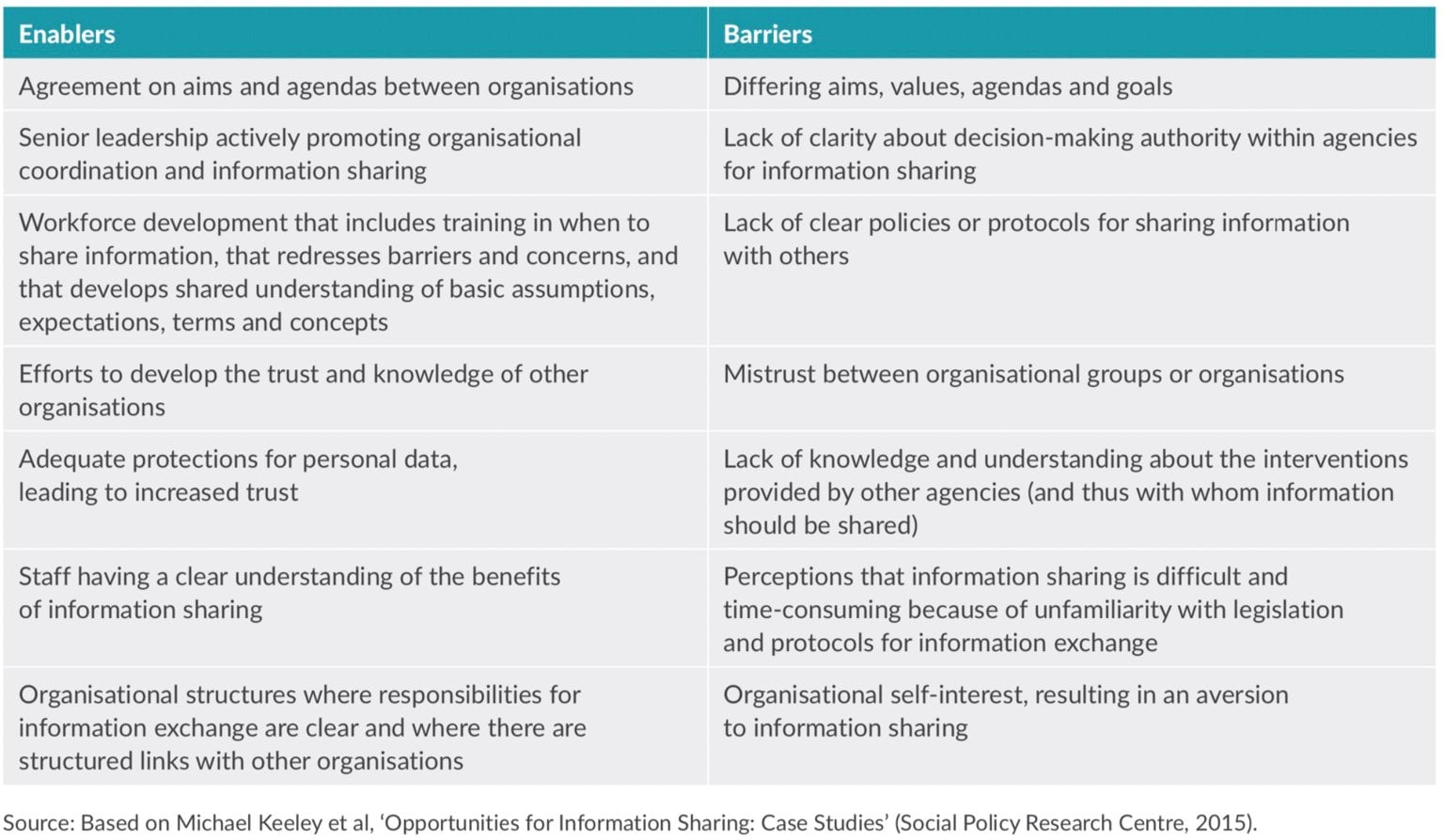

The key barrier for the rollout of the Scheme was the timing and/or sequencing of interdependent elements such as MARAM and training especially for those in Phase One organisations that have not historically been required to respond to or understand family violence risk. This barrier was consistently identified in each period of data collection. Other barriers include diverse and incompatible IT systems and platforms, and organisational cultures, such as the AOD sector, which have historically placed a high priority on client confidentiality. While Child Protection Practice advice was updated in September 2018 to address obligations under the Scheme, issues were consistently identified with Child Protection which is perceived as not readily sharing family violence risk relevant information, while continuing to seek high levels of victim/survivor information.

Key enablers are the ongoing strong support for the Scheme and its aims. This support is demonstrated through ongoing goodwill and commitment to work around any implementation barriers and engage in the work required to effectively operationalise the Scheme. The Scheme has provided an environment for greater interagency cooperation which has been widely embraced as a key enabler of information sharing. Another key enabler was the policy and protocol development work of lead agencies such as Victoria Police, the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria (MCV) and the Children’s Court of Victoria (CCV) and Corrections Victoria which have worked collaboratively to set up systems to effectively share perpetrator information. The advisors in the AOD and mental health agencies have been significant enablers of the Scheme. These positions play an important role in embedding information sharing practice and leading the necessary cultural change in Phase One organisations that have not previously dealt with family violence as part of their professional practice. Programs such as the Strengthening Hospitals Response to Family Violence Initiative have done some of the groundwork in preparing Phase Two for implementation of the Scheme. The developing maturity of family violence information sharing processes, less concern about workloads and potential adverse consequences, and growing experiences of 'good outcomes' has resulted in the overcoming of some barriers to the Scheme, which were identified during the earlier stages of implementation.

Recommendation 19In the lead up to Phase Two, a thorough audit of existing schemes promoting family violence literacy in Phase Two organisations should be undertaken. Careful consideration should be given to extending existing government initiatives such as the Strengthening Hospitals Response to Family Violence Initiative so they remain in place as Phase Two organisations are prescribed and in the process of embedding the Scheme. |

5. Has the Scheme resulted in increased levels of relevant information sharing between prescribed agencies?

The Scheme has resulted in an increase in both the quantity and risk-relevance of family violence information sharing, which has in turn led to enhanced understanding of the responsibilities and benefits of information sharing. There is good evidence of an increase in the sharing of perpetrator information. Broad-based support for the Scheme combined with the increase in the quantity of information sharing has worked to decrease fear of legal consequences and bolster pro-sharing attitudes. Workers have seen the benefits of the operation of the Scheme to effective and enhanced risk assessment in individual cases as a consequence of access to additional information and this has, in turn, enhanced sector understanding of the responsibility to share risk relevant information. While some workers continued to rely on pre-scheme processes for sharing, there was negligible evidence of inappropriate sharing.

6. Has the Scheme led to improved outcomes for victim/survivors and increased the extent to which perpetrators are in view?

The Scheme has produced positive outcomes particularly around the increased sharing of perpetrator information. One aspect supporting the extent to which perpetrators are kept in view is the further integration of men’s specialist family violence services, such as Men’s Behaviour Change Programs (MBCPs) into family violence risk assessment and management. There is some evidence that some victim/survivors are experiencing improved outcomes, but there are also concerns expressed by family violence specialists and other agencies about Child Protection’s focus on victim/survivor information and low levels of family violence risk relevant information sharing with family violence services in order to support the safety of women and children. The RCFV (2016) urged the strengthening of Child Protection practitioners’ understanding of family violence risk. In response to RCFV recommendations, ‘Tilting the Practice’ family violence training was rolled out to Child Protection practitioners in 2018 to encourage working supportively with mothers and focusing more on perpetrator behaviour. Yet, according to the evidence gathered in the Review, Child Protection did not always appear to fully recognise or effectively respond to family violence risk. This data suggests that work needs to continue to embed cultural change.

Recommendation 20Case studies which demonstrate positive outcomes of the Scheme should be used to illustrate the value of family violence information sharing in meeting its aims of enhancing women and children’s safety and keeping perpetrators in view. These case studies will be useful for enhancing practitioner understanding of the responsibilities of information sharing and the benefits of risk relevant sharing. |

Recommendation 21Prior to Phase Two specific practice guidance on and templates for family violence data security standards should be developed by FSV for training and implementation. These practice guidance and template materials should support the development of data security standards for family violence information and information sharing, in line with pre-existing privacy obligations. These materials should form part of the induction of Phase Two organisations into the FVISS. Training materials for Phase Two organisations should stress that data security standards must be transparent to victim/survivors. |

7. Has the Scheme had any adverse impacts?

The adverse impacts of the Scheme include concerns about the potential for women victim/survivors as well as perpetrators to disengage from support services. There are concerns that as part of the Mental Health Tribunal processes, the sharing of perpetrator information under the Scheme may be disclosed with a perpetrator applicant and that this could potentially impact on the safety of victim/survivors. There were also concerns about data security. The concerns were in many cases, based on hypothetical scenarios. There was a concern that these adverse impacts would be heightened for particular communities, including Aboriginal and LGBTIQ communities.

Recommendation 22The Victorian Government should work with the Mental Health Tribunal to ensure that victim/survivor safety is prioritised as part of its processes and to avoid the risks of any adverse consequences arising from the Scheme. In particular it should communicate with the Mental Health Tribunal about the family violence risks associated with disclosing to perpetrator/applicants any part of their file which indicates that family violence risk information has been shared without their knowledge under the Scheme. |

Introduction and context

Introduction and context of Review of the Family Violence Information Sharing Legislative Scheme Final Report.

The Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS - the Scheme) was established under Part 5A of the Family Violence Protection Act 2008. The Scheme commenced on 26 February 2018. The establishment of the Scheme was a key recommendation of the Royal Commission into Family Violence (State of Victoria 2016; Recommendation 5). The Royal Commission into Family Violence (RCFV) considered sharing information about family violence risk a critical to reform:

Sharing information about risk within and between organisations is crucial to keep victims safe. It is necessary for assessing risk to a victim’s safety, preventing or reducing the risk of further harm, and keeping perpetrators ‘in view’ and accountable.

The Scheme aims to better protect victim/survivors and enhance perpetrator accountability by facilitating, regularising and increasing the sharing of information about family violence risk across specialist family violence services and all other organisations and services that come into contact with victim/survivors or perpetrators.

The Royal Commission was particularly focused on the increased sharing of information about perpetrators. Organisations working directly with those experiencing family violence were authorised to share information where risk was assessed as ‘serious and imminent’ under the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 and the Health Records Act 2001. However, much of the shared information about family violence risk was information obtained from and about victim/survivors, usually with their consent. Perpetrator information was often less extensive and was less often shared.

At times, existing information about perpetrators was not shared because it was often considered unsafe to ask them to consent to share and the prevailing view was that their information could not be shared without consent except in exceptional circumstances. The Scheme has addressed barriers to sharing family violence risk information from and about perpetrators and created an obligation for proactive sharing of perpetrator information for a much wider group of organisations.

An independent Review of the FVISS is legislatively mandated to ensure that it meets its aims and avoids or minimises any adverse or unintended consequences. The Scheme has been rolled out to an Initial Tranche (February 2018) and Phase One (September 2018) of Information Sharing Entities (ISE).

There is a sub category of ISEs that are Risk Assessment Entities (RAE). These entities can request, collect and use information for a family violence assessment purpose, to establish and assess risk at the outset. The findings of this Review and consequent recommendations aim to ensure the optimal operation of the Scheme as it is extended to Phase Two in the first half of 2021 to include a much wider pool of universal services.

Family Violence Information Sharing reform background

It is well established that appropriate and timely sharing of information is critical in assessing, responding to and managing the risks of family violence. In Victoria and nationally, family violence has received unprecedented attention.

This attention has arisen from and contributed to greater awareness of the enormous costs of family violence for individuals, families, the community and to the economy. There is a growing body of research on the prevalence and impact of family violence. Intimate partner violence by men against women is the most common type of family violence and the evidence base about this type of violence is well established.

There is growing evidence and awareness about a range of different forms of family violence, including elder abuse and adolescent family violence. In addition, there is increasing knowledge about the distinctive impacts and manifestations of family violence in and on different communities, such as people living with disability, women from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) communities and the LGTBIQ community. While family violence, as the most common type of violence against women, is driven by gender inequality other types of discrimination and oppression such as ableism, ageism, heteronormativity, and precarious immigration status often intersect with gender inequality, in ways that compound and intensify the risk and impacts of family violence.

The continuing history of colonial relations of power mean that First Nations people, and First Nations women and children in particular, are disproportionally affected by family violence and often encounter barriers to accessing services. It is estimated that violence against women costs Australia $21.7 billion a year, of which $12.6 billion is related to violence by a partner (PriceWaterhouseCoopers 2015). Family violence has significant negative effects on women’s mental health (Franzway et al. 2015).

It is the leading cause of homelessness amongst women, contributing to a cycle of unemployment and poverty (State of Victoria (Department of Premier and Cabinet) 2016). Family violence is a recurrent factor in Child Protection notifications (State of Victoria (Department of Premier and Cabinet 2016). Exposure to family violence can cause significant harm to children, which can begin during pregnancy and progress through all stages of child development (State of Victoria 2016b).

Each week in Australia at least one woman is killed by a man, typically an intimate partner (Cussen, Tracy & Bryant 2015). Each year, 40 percent of all homicides in Victoria occur between parties in an intimate or familial relationship (State of Victoria 2016a). Australia wide intimate partner violence contributes to more death, disability and illness in women aged 18 to 44 than any other preventable risk factor (VicHealth 2004; Webster 2016). Family violence is a major social, criminal justice, human rights, economic and public health issue.

With unprecedented state and national attention directed to ameliorating the impacts of family violence, numerous Australian enquiries have recommended the introduction of legislation to improve family violence information sharing with the aim of enhancing victim/survivor safety and perpetrator accountability. These recommendations have resulted in most Australian jurisdictions adopting family violence information sharing legislation (Jones 2016, p. 20). While there had previously been information sharing between agencies about family violence risk, the legal basis for sharing such information was not always clear and concerns about client privacy were often prioritised over victim/survivor safety. Legislative family violence information sharing schemes provide an authorising environment for sharing family violence risk related information and signal a major change in the priority given to victim/survivor safety.

In Victoria, the RCFV (State of Victoria 2016) and the Coronial Inquest into the killing of eleven- year-old Luke Batty by his father (Coroners Court of Victoria 2015) recommended the introduction of a family violence information sharing scheme. Another key reform linked to the introduction of the FVISS is the review and redevelopment of the Common Family Violence Risk Assessment Framework (CRAF). Family Safety Victoria (FSV) is responsible for the implementation of the FVISS and the redeveloped CRAF, now renamed the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Risk Management (MARAM). The Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS) intersects substantially with the FVISS. Understanding the nature and dynamics of family violence and family violence risk is critical to the effective operation of the FVISS. In turn, family violence risk assessment and management cannot be effectively carried out without adequate knowledge of family violence risk (Family Safety Victoria 2019).

The FVISS has been implemented as part of wide ranging reform to the family violence prevention and response policy landscape. Other critical reforms, in addition to the MARAM and CISS, currently being implemented in Victoria include Roadmap for Reform: strong families, safe children; Free from violence – Victoria’s prevention strategy; initiatives as part of Building from Strength: 10-year industry plan for family violence prevention and response; and the extension of the Specialist Family Violence Courts model. This program of reform is a once in a generation opportunity to make progress towards eliminating family violence and creating a society free from violence. The RCFV made 227 recommendations, all of which the Andrews’ Labor government is committed to implementing. The Victorian government has invested $2.7 billion to achieve the reforms and a number of new family violence governance arrangements have been implemented including the creation of a Ministerial portfolio for the prevention of family violence, and the establishment of two dedicated entities focused on family violence prevention, Family Safety Victoria and Respect Victoria. The FVISS and the MARAM are critical centrepieces of the reforms. The RCFV set out an ambitious five-year time frame for the implementation of all of its recommendations. The aims of transformative policy change involving a wide range of workforces and government departments is complex and has required significant and sustained commitment from all involved.

The FVISS received Royal Assent on 13 June 2017 and commenced operation on 26 February 2018. The FVISS has two aims:

- to better identify, assess and manage the risks to adult and child victim/survivors’ safety, preventing and reducing the risk of harm; and

- to better keep perpetrators in view and enhance perpetrator accountability

A phased approach has been taken to the implementation of the FVISS. This approach has comprised three distinct stages; Initial Tranche, Phase One, commenced in early and late 2018 respectively and Phase Two, to commence in the first half of 2021. This approach has been taken to ensure workforce readiness and sector capacity to meets the aims of the Scheme with a critical focus on minimising the risk of adverse or unintended consequences. The Initial Tranche was limited to entities with a level of ‘criticality, family violence literacy and ability to operate in a regulatory environment’ (Family Safety Victoria 2017b, p. 3).

The relatively small number of Initial Tranche entities are the most well-informed about family violence, its gendered dynamics, family violence risk, and the principles underpinning family violence information sharing. Initial Tranche entities were considered to be in the best position to implement and absorb the initial FVISS implementation (c. 5,000 workers) and were prescribed on 26 February 2018.

Phase One (c. 38,000 workers) commenced on 27 September 2018. Phase One includes organisations and services that hosted Initial Tranche entities, and whose core business is not family violence risk assessment and response but that spend a significant proportion of their time responding to victim/survivors or perpetrators, as well as non-family violence specific support or intervention agencies.

Phase Two entities (with c. 370,000 workers) are due to be prescribed in the first half of 2021. Phase Two includes universal services and first responders, such as health, education and social services, that are often early contact points for victim/survivors (Family Safety Victoria 2019, pp. 15-6). Research indicates most victim/survivors do not report family violence to police or seek assistance from specialist family violence services (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2017). In these cases, Phase Two organisations and services may be an early or sole point of contact for victim/survivors.

See Table 1 below for a summary of each of the three stages of implementation of the FVISS. For a full list of entities prescribed in each stage see Appendix One.

Table 1: Stages of FVISS Implementation

|

|

Initial Tranche |

Phase One |

Phase Two |

|

Date Prescribed |

26 February 2018 |

27 September 2018 |

First half of 2021 |

|

Type of Entities |

Specialist family violence services and other organisations with high level of family violence risk literacy. |

Entities whose core business is not directly related to family violence, but which spend a significant proportion of their time responding to victim/survivors or perpetrators. |

Universal services and first responders, such as health, education and social services, that are often contact points for victim/survivors. |

|

Number of workers |

c. 5,000 |

c.33,000 |

c. 370,000 |

|

Rationale |

These workforces best placed to absorb and begin the implementation process. |

Typically providing services to client group that are understood to include significant proportion of victim/survivors or perpetrators. |

Victim/survivors often do not seek out specialist services so these services may often provide opportunities for intervention that would not otherwise occur. |

|

Pre-existing family violence risk management knowledge |

Some 30% used CRAF*

|

Very limited |

Very limited |

*Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor (2020)

A key stakeholder in the FVISS Review is FSV which is responsible for the FVISS reform and its Review. The Information Sharing/MARAM Working Group, convened by FSV, including representatives from FSV, DHHS, DET, Victoria Police, the Magistrates’ and Children’s Courts and Department of Premier and Cabinet, assisted to guide the development of this project providing feedback on the Project and Evaluation Plan developed by Monash, the Baseline Report, the Interim Report, the Updated Evaluation Framework and this Final Report.

Early in the Review process a document for managing independence was jointly developed and agreed by FSV and the Review team. Those managing and assisting the Review at FSV proactively provided a large amount of relevant documentation to assist the Review process. They promptly and fully responded to requests for further information, provided pathways for accessing key stakeholders, assisted with distribution of information about the Review to relevant individuals and organisations, and arranged for the Review team to be briefed about a range of intersecting reforms or components of the FVISS including MARAM, CISS, Orange Door and CIP. Regular face-to-face meetings were held where issues were discussed and clarified and Review related challenges were identified and addressed. An Interim Report on the implementation of the FVISS to the Initial Tranche was provided to FSV in June 2018. The Interim Report included a number of recommendations. The Review team presented to FSV on the findings for this Final Report in February 2020. The presentation provided an opportunity for discussion and clarification of issues prior to the finalisation of the Report. Annexure One provides a record of FVS, DHHS and DET feedback on this Report and the Monash response. Annexure Two provides information about conflict of interest.

Those services and organisations that were prescribed as ISEs in the Initial Tranche and Phase One are key stakeholders in the FVISS, along with FSV and other government departments. Practitioners and managers from these ISEs have been engaged as participants in the Review through the surveys, focus groups and/or interviews. In addition, a number of family violence experts have been interviewed. A host of submissions made to FSV by stakeholders as part of the consultation process at various stages of the FVISS implementation have also been considered in the Review (see Appendix Nine for a full list of submissions reviewed). Finally, victim/survivors are critical stakeholders and a total of 26 women took part in focus groups and interviews.

Family Violence Information Sharing Review framework

The FVISS legislation includes a mandated independent Review after two years of operation. The Review considers both the process of implementation and outcomes. As set out in the limitations section 6.5, however, for various reasons the outcomes of the reform are difficult to identify with a high degree of confidence at this point in time.

Though a number of family violence information sharing schemes have been introduced in Australian and internationally, few have been systematically evaluated (State of Victoria 2016: 158; see Appendix Three for a list of these schemes and relevant evaluations). Government-funded evaluations and recent academic literature on family violence information sharing primarily focus on the broader mechanisms of multiagency coordination and collaboration, rather than information sharing specifically (see the Literature Review, section 7). The Review of the FVISS provides a unique opportunity to assess the effectiveness of a legislative family violence information sharing scheme. Existing research, mainly based on reviews and evaluations of child information sharing schemes, consistently concludes that the enabling effect of legislation on information sharing alone is limited and that messaging about information sharing, practice guidance, training, operational and organisational issues are more significant as barriers and enablers of information sharing than legislation or policy.

Review purpose

This two year Review is designed to evaluate the implementation and outcomes of the Scheme to ensure that it is being implemented effectively and adverse or unintended consequences are limited and/or addressed. In particular it is designed to inform the process of implementation to Phase Two organisations and services. The Initial Tranche and Phase One implementation involved c. 408,000 workers in total. Phase Two includes c. 370,000 workers. Phase Two workers will typically have considerably lower levels of family violence risk literacy than the Initial Tranche and many Phase One workers. The large number of people who will be authorised to share family violence risk relevant information in the next phase of FVISS implementation, combined with the relatively low level of family violence risk literacy amongst these workers may increase the risks of adverse or unintended consequences. While these risks cannot be eliminated, they can be mitigated by capturing and diligently applying the learnings from this two year Review of the implementation and outcomes of the Scheme in its earlier stages. As pointed out by the (former) Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor there is significant risk inherent in family violence reform activity generally and family violence information sharing in particular (Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor 2019). The Review of the FVISS is critical in assisting to ensure that the FVISS meets its primary aim of improving the safety of victim/survivors and enhancing perpetrator accountability and mitigating any risks to victim/survivors arising from the FVISS.

This Review Report, based on the reflections, insights and experiences of practitioners, managers, experts and victim/survivors, supplemented by review of relevant documents, training observations, sharing data from lead agencies and a comprehensive literature review, is designed to maximise the effectiveness of the FVISS. The Report, including key findings, recommendations and discussion, is offered with a view to building upon the substantial achievements in the rollout in Initial Tranche and Phase One organisations as the Scheme is extended to a larger number of practitioners employed in more universal non-specialist entities and services in 2021.

Key review questions

The Review was guided by seven key questions related to implementation and outcomes of the FVISS. These questions were set out in FSV’s Request for Quote for the Review of the FVISS in 2017. The key questions were considered by the Review team to be succinct, clear, pertinent and comprehensive and remained unchanged during the Review. These key questions, sub-questions, and topics are set out below. Some of the sub-questions and topics were adjusted during the Review to reflect emerging issues.

Table 2: FVISS review questions

Consider: Effectiveness of training, guidelines, sector grants, Enquiry Line, extent that legislative requirements have been embedded in practice guides and procedures of ISEs. |

Consider: Whether elements have been delivered on time, to the necessary work forces and parts of work forces. |

Consider: Any adverse impacts on workforces in ISEs, e.g. increased workload (additional time taken each time information is shared and/or greater volume of information sharing) and changes in ways of working with clients. |

Consider: What are the key lessons to inform further roll out of the Scheme, including:

Plus: have initial barriers identified through the Review been addressed? |

Consider: Has the Scheme resulted in the following results for service workers in ISEs:

Plus: have these factors led to an increase in relevant information being shared (i.e. information that has informed risk assessment or risk management)? |

Consider: Has information sharing increased the extent to which perpetrators are in view? Has information sharing improved victim/survivor’s experience of services (e.g. avoiding re-telling of story, obtaining risk relevant information about perpetrators)? How has the scheme impacted on adolescents as victim/survivors and perpetrators of family violence? Is there evidence to show that information sharing under the Scheme has decreased the risk or incidence of family violence? |

Consider: Has there been any decreased engagement in services by victim/survivors or perpetrators, increased risk or incidents of family violence, increased privacy breaches, other adverse impacts? Has misidentification of the primary perpetrator been an issue? What has been the impact on victim/survivors or perpetrators from diverse communities? What has been the impact on Aboriginal people including Aboriginal women? Has sharing of information without consent (as permitted by the law when assessing and managing risks for children) led to a decrease in victim/survivor engagement with the service system? Has there been an increase in sharing of information that is irrelevant or inappropriate? Are any changes to the legislation or other aspects of the Scheme necessary to address adverse impacts or otherwise improve the scheme? |

The table below provides an overview of the evaluation framework

Table 3: Evaluation framework

|

Key evaluation question |

Indicator |

Measure |

Data source |

|

Participants’ perceptions regarding effective implementation generally and, particularly in relation to sub-question elements.

|

Question to participants as per key question 1 and sub-questions. |

Focus groups with ISEs services providers, managers and experts.

Interviews with ISEs service providers, managers and experts. |

|

Survey One and Two enabled measures of behaviour, attitudes, and relevant information regarding information sharing processes and systems pre-implementation of ISS for Initial Tranche and Phase One workforces and post-implementation. |

Relevant questions in Survey One and Two. |

Survey One and Two.

|

|

|

Analysis in relation to the Review questions. |

Relevant document content. |

Any documents relating to sub-elements of the question. |

|

|

The material gaps between the plans and actions. |

Reconciliation of implementation plans against implementation actions. |

FSV implementation plans. |

|

Participants’ perceptions regarding awareness of the FVISS and its implementation relevant to overall delivery. |

Question to participants as per key question 2 and sub-questions. |

Focus groups with ISEs service providers, managers and experts. Interviews with ISEs services providers, managers and experts. |

|

|

|

Relevant questions in Survey One and Two. |

Survey One and Two. |

|

|

Upward trends in the number of complaints. Upward trends in the number of substantiated/ upheld complaints. Considerations related to the seriousness of complaints and any particular impacts on groups considered particularly vulnerable. |

Number and nature of complaints to ISEs and Privacy Commissioners. |

Complaints to Privacy Commissioners and ISEs. |

|

Participants’ perceptions regarding impacts of the scheme generally and, particularly in relation to sub-question elements. |

Question to participants as per key question 3 and sub-questions. |

Focus groups with ISEs services providers, managers and experts. Interviews with ISEs services providers, managers and experts. |

|

|

|

Relevant questions in Survey Two. |

Survey One Two. |

|

|

Participants’ perceptions regarding information sharing practice and experience, and attitudes to information sharing, noting that key barriers and enablers for implementation identified in the Interim Report were timing; communication; legal, policy and practice frameworks; and existing systems and data security. |

Question to participants as per key question 4 and sub-questions. |

Focus groups with ISEs services providers, managers and experts. Interviews with ISEs services providers, managers and experts. |

|

|

Relevant questions in Survey Two. |

Survey Two. |

|

|

Participants’ perceptions regarding information sharing practice and experience including information requesting and, particularly in relation to sub-question elements. |

Question to participants as per key question 5 and sub-questions. |

Focus groups with ISEs services providers, managers and experts. Interviews with ISEs services providers, managers and experts. |

|

Survey Two will measure the experience of Initial Tranche and Phase One workforces after the Phase One roll out, to capture the impact the scheme has had on information sharing, changes to risk assessment and risk management as a consequence of ISS implementation and the adequacy of training to prepare workers for ISS. This data will be compared to findings from Survey One. |

Relevant questions in Survey One and Two. |

Survey One and Two. |

|

|

Participants’ perceptions regarding improved outcomes for victim/survivors and the extent to which perpetrators are in view, and particularly in relation to sub-question elements. |

Question to participants as per key question 6 and sub-questions. |

Focus groups with ISEs services providers, managers and experts. Interviews with ISEs services providers, managers and experts. |

|

|

Relevant questions in Survey Two. |

Survey Two. |

|

|

Perceptions of victim/survivors and perpetrators particularly in relation to the relevant sub-questions.

|

Question to participants as per key question 6 and sub-questions. |

Interviews and focus groups with victim/survivors and perpetrators. |

|

|

Participants’ perceptions regarding information sharing practice and experience generally and, particularly in relation to sub-question elements. |

Question to participants as per key question 7 and sub-questions. |

Focus groups with ISEs services providers, managers and experts. Interviews with ISEs services providers, managers and experts. |

|

|

Relevant questions in Survey Two. |

Survey Two. |

|

|

Perceptions of victim/survivors and perpetrators particularly in relation to the relevant sub-questions. |

Question to participants as per key question 7 and sub-questions. |

Interviews and focus groups with victim/survivors and perpetrators. |

Scope

This two-year Review focuses primarily on the first twenty-two months of the implementation of the FVISS. The Review formally commenced in October 2017.

The Scheme commenced in February 2018. The temporal scope of the Review in terms of data collection from key stakeholders was November 2017 to December 2019.

The Review’s primary stakeholder groups in terms of data collection are practitioners and managers in the Initial Tranche and Phase One organisations and services, family violence experts and victim/survivors.

Data collection from these key stakeholders commenced with a survey prior to the implementation of the Scheme to the Initial Tranche and Phase One in order to construct a working baseline from which to measure the impacts of the establishment and operation of the FVISS.

There were two periods of Interviews and focus groups after the implementation of the Scheme to the Initial Tranche and the Phase One. Data gathering with stakeholders was completed in December 2019.

The collection and review of relevant documents continued through the whole period of the Review. The literature review was initially undertaken in April 2018 and was updated over the duration of the Review (see section 6.4 on timings below for further information on the timings related to key Review tasks).

The MARAM, CISS, and the Orange Door reforms are closely related to the FVISS. In addition, the Central Information Point (CIP) is an important component of the FVISS. The CIP allows the MCV and CCV, Victoria Police, Corrections and the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) to consolidate and share critical information about perpetrators of family violence, when requested from within an Orange Door or Berry Street, providing a single comprehensive report to frontline family violence specialists.

The impact of these reforms on the FVISS, or as part of it, are referred to throughout the Report as relevant to the specific Review questions. However, the MARAM, Orange Door, CISS and CIP reforms have been or are subject to separate reviews and are not a primary focus of this Review.

Design, method and data

Design, method and data for Review of the Family Violence Information Sharing Legislative Scheme Final Report.

The research was guided by the seven key questions related to the implementation and outcomes of the FVISS. The research involved a multi methods approach including qualitative and quantitative methods, document review, training observation and a comprehensive literature review.

Review design, method and approach

The research designed included surveys, interviews, focus groups, document review, training observations, quantitative data from lead agencies, and a comprehensive national and international literature review. The diagram below captures the Review method.

Surveys were the primary quantitative method with two surveys used for this Review. While the surveys were both quantitative (multiple choice and scale responses) and qualitative (open-ended questions), the large number of quantitative questions means the survey focuses primarily on breadth over depth by capturing a large number of responses with limited capacity for detail. The surveys were designed to gain a broad understanding of practitioners’ experiences, attitudes and practices in relation to family violence information sharing and to enable some insight into shifts over time, post-implementation, regarding attitudes and practice.

In lieu of any existing and accessible Client Relationship Management (CRM) records which capture the history of family violence information sharing practice, a survey was considered the most appropriate method to collect baseline data. The items in the baseline survey, Survey One, were pre-FVISS measures of formal and informal information sharing practices and perceptions about information sharing in the Initial Tranche and Phase One workforces. Survey Two was undertaken with the Initial Tranche and Phase One approximately 12-18 months after implementation in order to capture the impact of the FVISS. Survey One questions were mapped to align with the Review questions that focus on the impact of the initial implementation of the FVISS. Outcomes and impacts of the implementation of the FVISS on information sharing were measured through Survey Two that provided data about changes benchmarked against the baseline established in Survey One. The survey design across Survey One and Two was a panel design, where we sought to analyse individual responses at two points in time, to more accurately measure change in practice and attitudes. However, the attrition rate between surveys was too high and the panel sample was not large enough to produce robust panel data. Therefore, the Report relies on broad trend data to review change between Survey One and Two regarding attitudes and practice.

Survey One included 83 questions and Survey Two included 95 questions. Both surveys comprised multiple choice, Likert-scale responses (i.e. questions with graded response options) and open-ended questions, which represent the surveys’ qualitative element. The surveys were conducted using Qualtrics. Survey One was piloted with 13 Victorian family violence practitioners and reviewed by Family Safety Victoria (FSV). Based on the feedback minor modifications to the survey were made prior to its release. Survey Two was reviewed by FSV. This data complements and captures broad attitudes and experiences, that align with the more detailed interviews and focus group discussions.

Quantitative data on the volume of post-scheme information sharing was requested and received from lead organisations; Victoria Police, DHHS, the Department of Justice and Community Safety, MCV and CCV. These organisations were asked how many requests for information they had received and made under the Scheme and details about which organisations were requesting information and which organisations they were sharing information with. Further details were also requested such as whether the information related to victim/survivors, perpetrators, children or others was requested and how many requests were denied. A month by month breakdown of the data was requested. There is a lack of of legislative obligation to record the volume of information sharing or details about such sharing under the Scheme. As a result of this, the data supplied by each of the lead organisations varied in content and format.

The qualitative part of the Review methodology (interviews and focus groups) was designed to capture in depth and detail the experienced and impact of the FVISS, to illuminate and explore key issues in the Review’s Interim and Final Reports. Qualitative research methods were used to understand the experiences, attitudes and practices of family violence information sharing. The qualitative methods involved interviews and focus groups that sought the perceptions, experiences and opinions of participants. These were undertaken in two periods; after implementation of the Scheme to the Initial Tranche and after implementation to Phase One. Qualitative research methods produce robust, rich and detailed data that is not readily available via quantitative instruments: they encourage disclosure and reflection amongst participants. The primary skills involved are attentive listening and facilitation of discussion that is simultaneously focused and open. Focus groups allow for the gathering of sufficient relevant information while openness ensures space for unanticipated opinions or information to be captured. A feature of qualitative research is that participants and interviewers or focus group facilitators jointly shape the discussion that takes place. In a process of reform such as the FVISS that is built on the existing expertise of practitioners and the knowledge and expert insights of those who have experienced family violence, such methods are particularly valuable.

Interviews and focus groups were based on semi-structured questions developed from the key Review questions (see Appendix Four). These questions were refined slightly after early focus groups and interviews. Semi-structured questions act as a guide to discussion rather than a firm schedule. In some cases, the interviewer/facilitator will ask each question on the interview schedule; at other times the interviewee or participant/s with a good understanding or strong opinions of the topic area, will cover all relevant issues with little prompting. In addition, participants may provide information they consider is relevant, even if it does not align directly with key questions identified by the interviewer/facilitator. In qualitative research, such additions are viewed as important data as they reveal the ways in which issues are understood by participants and can illuminate or point to ‘unintended consequences’ that may occur in practice.

Notes were taken of pertinent issues in focus groups and interviews with practitioners and experts and shared between Review team members. Trend data from the focus groups and interviews was used to aid discussion in future focus groups and interviews and as a way of focusing questions or seeking further data where relevant. Where focus groups were convened with specific organisations or sectors, discussion concentrated on those aspects most relevant to the knowledge and practise base of those participants (see Appendix Five for a list of focus groups). Where people were unable to attend a focus group they were invited to participate in a phone interview. Two Review team members typically attended each of the focus groups.

Participation by victim/survivors: This process was carefully managed to ensure appropriate and adequate recognition of participant needs. These participants are critical to the Review and the Report. Women were recruited through support services (family violence and disability services) and so had received the support of these services prior to their participation. Women were provided with vouchers to support their participation and in recognition of the provision of their expertise. The focus of the interviews was on women’s experiences of service responses, particularly as pertinent to the sharing of family violence information. The participants were not required to discuss their experiences of family violence. The interviewers have expertise in relation to the impact of family violence and the nature of the service and response systems. The victim/survivor participants had significant experience of having information gathered and/or shared as they interacted with various services. The victim/survivor participants had control over the timing and location of their engagement with the Review. Most were interviewed or attended focus groups at specialist family violence services, locations where they felt comfortable. Others elected to participate by phone in order to better ensure their contributions were confidential.

A wide range of relevant documents and data including training content, training participation and feedback, Enquiry Line data, stakeholder submissions, FSV plans, reports to FSV about the implementation of the FVISS and other relevant reforms, and relevant Regulatory Impact Statements, were reviewed. A comprehensive literature review was also undertaken to understand the international and national context in which family violence schemes have been implemented and to take into account the learnings of reviews of these schemes in other contexts.

The advantages of the multi methods design are that it allows for breadth (surveys and other quantitative data), depth (interviews and focus groups) and context (literature review). The documents, depending on category, provided context, quantitative data, or the views of stakeholders. The range of data sources allows for robust triangulation whereby the themes present in one data set can be matched, confirmed or contrasted with those from other sources.

Participants, data sources and analysis

Participants

There were more than one thousand participants in the Review over the two data collection periods. Two hundred stakeholders were interviewed or took part in focus groups and 792 people responded to the survey. Those who participated in focus groups or responded to the surveys included workers and managers in the Initial Tranche and Phase One organisations, family violence experts and victim/survivors. Family violence experts included family violence trainers, academics, those working in peak organisations, policy leaders, managers, family violence advisors and judicial officers.

Recruitment for the surveys, interviews and focus groups was facilitated through multiple pathways

These pathways included the Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre (MGFVPC) and FSV website, FSV newsletters, the MGFVPC monthly e-Digest, emails to all relevant peak bodies and government departments. Where FVISS training participants provided permission for their details to be shared for the purposes of recruitment to the Review these potential participants were emailed directly with an invitation to take part in the Review. Each survey was distributed through the same pathways via a survey link along with information about the survey and invitations to participate in the survey and share it with other practitioners if appropriate.

The participation of geographically diverse stakeholders was considered important. Four focus groups were held in regional or remote areas, including Shepparton, Sale, Bairnsdale and Geelong.

Victim/survivors were recruited through specialist family violence services. This process was designed to assist in ensuring that they were safe and adequately supported throughout their participation. Prioritising victim/survivor safety is the primary logic for the reform under Review. Such consideration is an integral part of an ethical approach to engaging with victim/survivor participants. Victim/survivors were provided with a $50 Coles voucher as recognition for their sharing of expertise and experiences.

All potential participants were offered the opportunity to participate by telephone or via email if attending a focus group or interview was not convenient or possible.

The Review did not aim for a representative sample; that is representation that mirrors proportionally the number of each category of ISE organisation. However, it did seek a wide range of views, thereby reflecting the diversity of organisational types included in the FVISS. Where participation by a particular category of ISE in the Initial Tranche or Phase One was not readily forthcoming efforts were made to recruit participations from these categories. Such efforts included direct contact with potential participants where details were publicly available, and, where appropriate, contact with a peak body, relevant government department, or particular ISEs.

Recruiting participants in the second period of data collection proved more challenging than in the first. Recruiting workers for focus groups and managers for interviews required more sustained effort and the participant numbers in Survey Two (258) were substantially less than for Survey One (534). One explanation for this may be ‘research fatigue’. Family violence practitioners and managers are being recruited to participate in multiple reviews, while services are facing increased demand and while implementing multiple reforms.

Initially it was intended that perpetrators of family violence would be included as participants in the Review. We anticipated that access to known perpetrators of family violence would be facilitated through Men’s Behaviour Change Programs (MBCP). However, despite best attempts and the willingness of men’s services to engage with the review, recruitment proved challenging. We note that No To Violence, the peak organisation for MBCP, was willing to assist with recruitment. In addition, the Review team have a number of established relationships with individual MBCP and these were contacted directly with requests to facilitate access to potential participants. However, sustained attempts to recruit perpetrators were unsuccessful. The barriers to recruitment included:

- the workloads of MBCP: many have substantial waiting lists. As a result of these pressures, a number of MBCP felt unable to commit to facilitating perpetrator involvement in the Review