- Published by:

- Family Safety Victoria

- Date:

- 24 Feb 2023

Acknowledgements

Aboriginal acknowledgement

The Victorian Government acknowledges Victorian Aboriginal people as the First Peoples and Traditional Owners and Custodians of the land and water on which we rely. We acknowledge and respect that Aboriginal communities are steeped in traditions and customs built on a disciplined social and cultural order that has sustained 60,000 years of existence. We acknowledge the significant disruptions to social and cultural order and the ongoing hurt caused by colonisation.

We acknowledge the ongoing leadership role of Aboriginal communities in addressing and preventing family violence and will continue to work in collaboration with First Peoples to eliminate family violence from all communities.

Victim survivor acknowledgement

The Victorian Government acknowledges victim survivors. We keep at the forefront in our minds all those who have experienced family violence or other forms of abuse, and for whom we undertake this work.

Family violence support

If you have experienced violence or sexual assault and require immediate or ongoing assistance, contact 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) to talk to a counsellor from the National Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence hotline.

For confidential support and information, contact the Safe Steps 24/7 family violence response line on 1800 015 188.

If you are concerned for your safety or that of someone else, please contact the police in your state or territory, or call Triple Zero (000) for emergency assistance.

Message from the Minister for Prevention of Family Violence

I am proud to present the annual report on the implementation of the Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM) 2021–22.

This report outlines the key activities and achievements of Victorian Government departments, sector peak bodies and prescribed organisations to align their policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools to MARAM.

MARAM is a critical part of Victoria’s family violence reform, enabling workforces across a range of sectors to identify and respond to family violence more effectively.

Ending family violence remains a government priority. The Victorian Government has invested more than $3.7 billion since the Royal Commission into Family Violence to prevent and respond to family violence. This includes $97 million of investment in the Victorian State Budget 2021–22 to support changes to keep people safer, including implementing MARAM, alongside critical information-sharing reforms.

The effective rollout of MARAM and information sharing requires training for over 370,000 workers across a range of workforces. Since the commencement of the reforms in 2018, I am pleased to highlight that:

- more than 107,000 professionals have undertaken training in MARAM and the related information-sharing schemes

- more than 82,000 risk assessments and safety plans have been undertaken (using MARAM online tools)

- more than 15,000 Central Information Point reports have been delivered.

In this fourth annual report into the operation of the MARAM Framework, it is clear that confidence in undertaking risk assessments and information

sharing under MARAM continues to grow, as we build a system that keeps people safer.

I would like to thank all former and current ministers with framework organisations withintheir portfolios for the continued work undertaken

to implement this critical reform. This report is consolidated from my own portfolio report and those provided to me by:

- the Hon. Melissa Horne MP, (former) Minister forConsumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation

- the Hon. Jaclyn Symes MP, Attorney-General

- the Hon. Mary-Anne Thomas MP, Minister for Health, (former) Minister for Ambulance Services

- the Hon. Lizzie Blandthorn MP, Minister for Child Protection and Family Services, Minister for Disability, Ageing and Carers

- the Hon. Gabrielle Williams MP, Minister for Mental Health

- the Hon. Anthony Carbines MP, Minister for Police, Minister for Crime Prevention

- the Hon. Ingrid Stitt MP, Minister for Early Childhood and Pre-Prep

- the Hon. Natalie Hutchins MP, Minister for Education

- the Hon. Danny Pearson MP, (former) Minister for Housing

- the Hon. Sonya Kilkenny MP, (former) Minister for Corrections, (former) Minister for Youth Justice, (former) Minister for Victim Support.

I would also like to acknowledge the work across government, the sector and community services for their continued dedication to improving our response to family violence. This includes Family Violence Regional Integration Committees, peak bodies, Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations, the Strengthening Hospital Responses to Family Violence resource centre, and many other organisations and services who are ensuring MARAM practice is a reality.

I particularly wish to acknowledge the work of Specialist Family Violence Services (including sexual assault services) and The Orange Door Network who are crucial partners in our efforts to effectively respond to family violence.

I would also like to thank all those with lived experience, in particular, past and present members of the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council,

for their ongoing contribution and influence in the delivery of MARAM practice guidance.

Finally, as we progress these important reforms, I acknowledge all those across government and the services sector who have contributed to this report, and those who dedicate their time, passion and effort to improving the safety of all Victorians.

The Hon. Ros Spence MP

Minister for Prevention of Family Violence

Whole of government snapshot 2021–22

- 107,456 workers have undertaken training in MARAM and the related information-sharing schemes from inception until 30 June 2022.

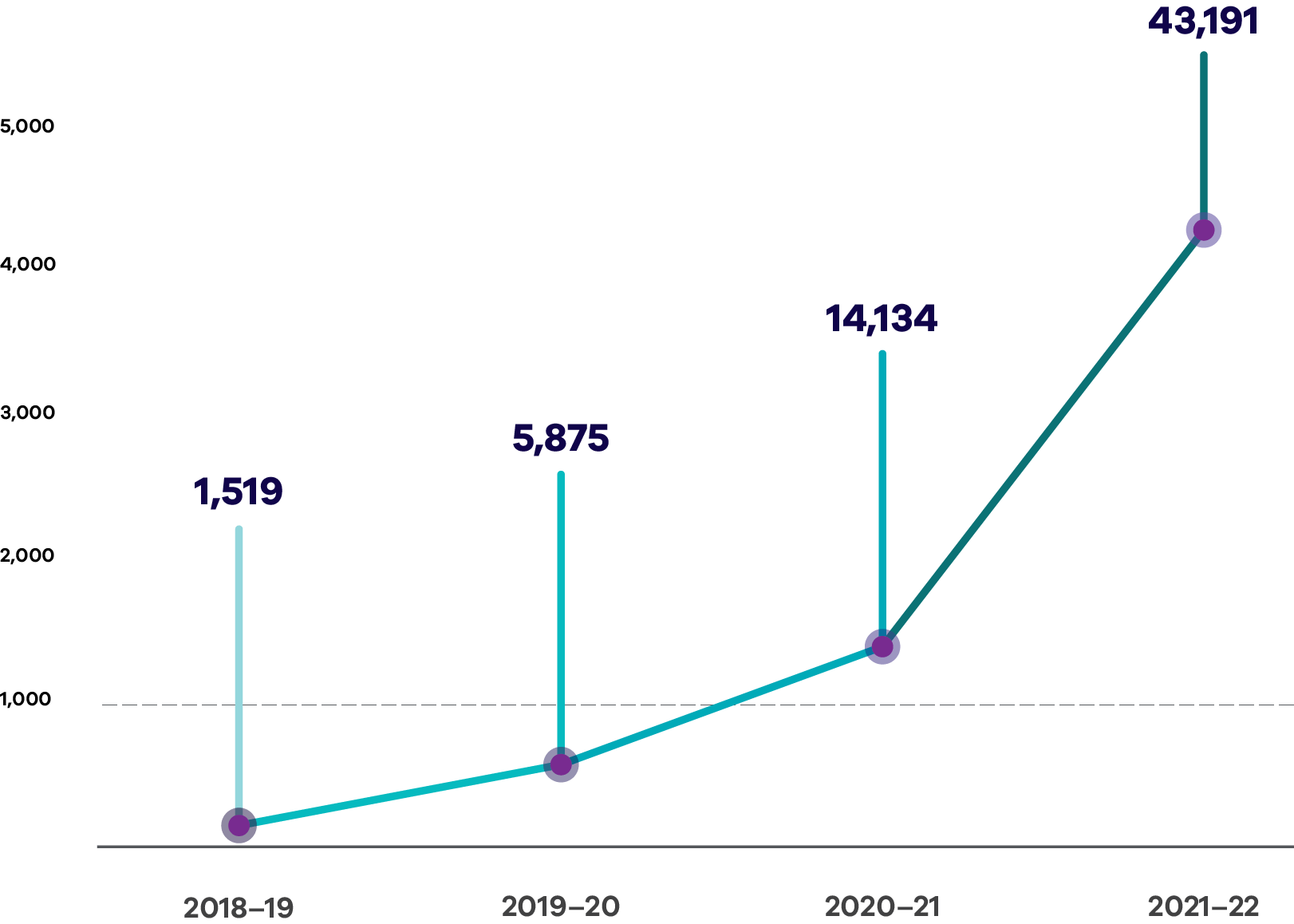

- 43,191 workers received MARAM training in 2021–22.

- over 15,150 Central Information Point reports have been delivered from commencement in April 2018 until 30 June 2022.

- over 82,000 risk assessments and safety plans have been undertaken using The Orange Door online systems (Tools For Risk Assessment.

and Management and Client Relationship Management System) since inception. - 4530 Central Information Point reports delivered during 2021–22.

- The MARAM website has averaged month (Sept 21 to Sept 22) 60,000 page views per month (Sept 21 to Sept 22).

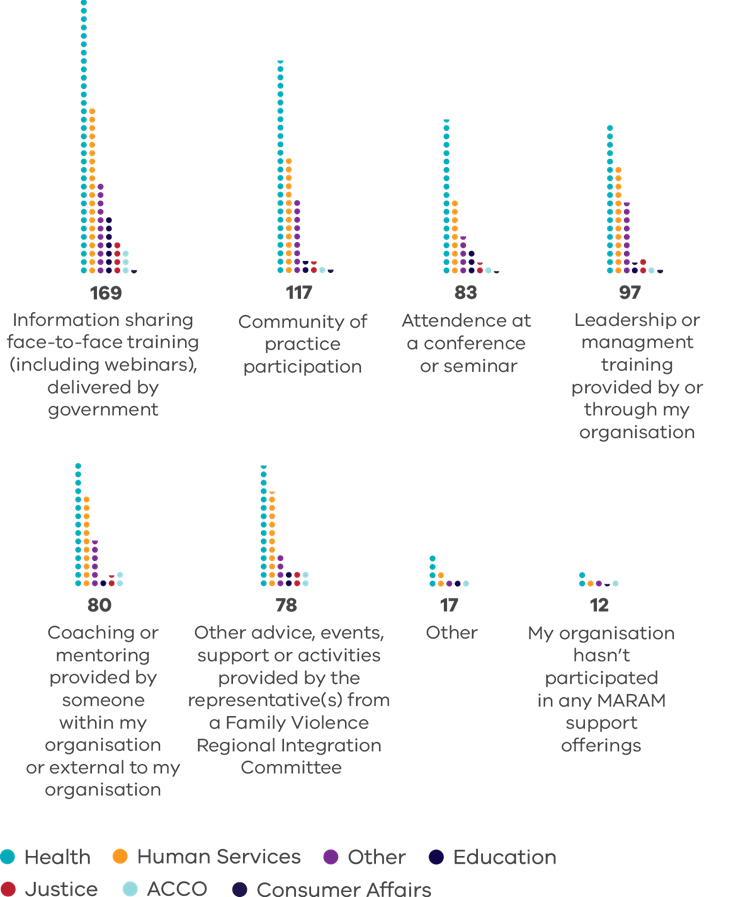

- 243 organisations responded to the MARAM Annual Survey, representing over 376 workforces.

Introduction

The Royal Commission into Family Violence (the Royal Commission) was established in 2015 after a number of family violence-related deaths in Victoria – most notably, the death of Luke Batty.

The role of the Royal Commission was to find ways to prevent family violence, improve support for victim survivors and to hold perpetrators to account.

The Royal Commission found existing programs were not able to:

- reduce the frequency and impact of violence

- prevent violence through early intervention

- support victim survivors

- hold perpetrators to account for their actions

- coordinate community and government services.

The Royal Commission identified 227 recommendations for the family violence system. Recommendation 1 was for the Victorian Government to review and begin implementing a revised family violence risk assessment and risk management framework, in order to deliver a comprehensive framework that sets minimum standards, roles and responsibilities for screening, risk assessment, risk management, information sharing and referral throughout Victorian agencies. The Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM) is the response to Recommendation 1.

Section 193 of the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic) requires a report to be tabled in Parliament annually on the progress of MARAM implementation[1]. This is the fourth report to be tabled.

Implementation of the reforms is structured with Family Safety Victoria as the lead. This requires Family Safety Victoria to design and develop the policies, resources and training for the reforms. Family Safety Victoria also oversees implementation across the Whole of Victorian Government (WoVG), through governance, reporting and annual surveys.

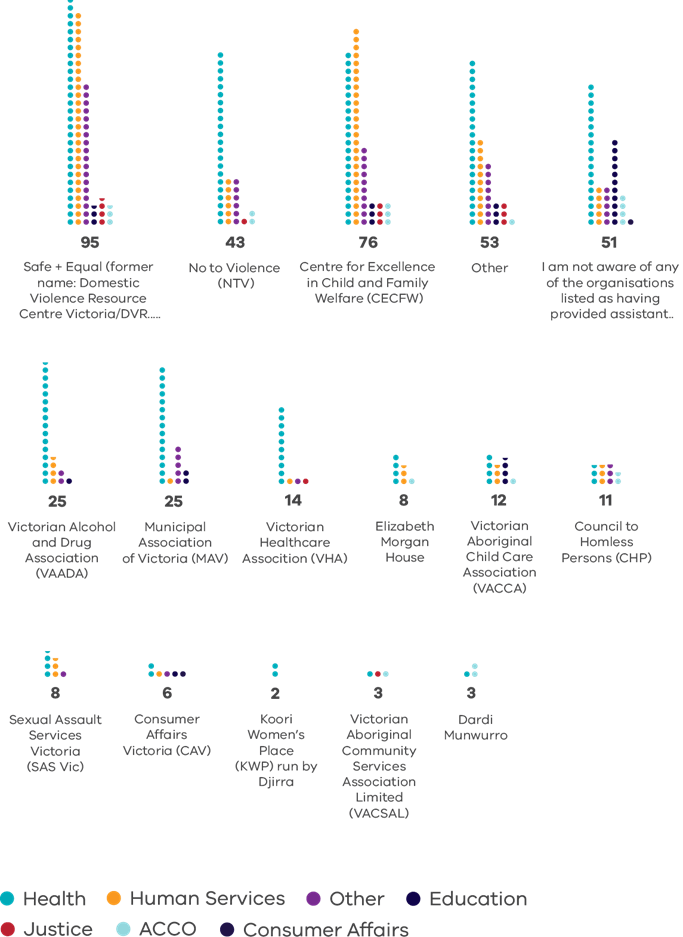

Departments are responsible for tailoring the policies, resources and training to their specific workforce needs, communicating about the reforms and responding to barriers in the workforces[2]. Sector peak bodies and leading organisations are funded to support implementation more directly with practitioners. Family Safety Victoria has funded 16 organisations in 2021–22 through ‘sector capacity-building grants’.

Those organisations are:

- Adult Multicultural Education Services (AMES)

- Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare (CFECFW)

- Council to Homeless Persons

- Dardi Munwurro

- Djirra

- Elizabeth Morgan House

- Jewish Care

- No to Violence (NTV)

- Safe and Equal

- Sexual Assault Services Victoria

- Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA)

- Victorian Aboriginal Community Services Association Limited (VACSAL)

- Victorian Alcohol and Drug Association (VAADA)

- Victorian Health Association (VHA)

- Whittlesea Community Connections

- Youth Justice.

Chapter 1 lists the portfolios providing reports. Chapter 2 is a note on the language used throughout the report, which aligns to MARAM. Chapter 3 summarises the legislative provisions, regulations and policies developed to create MARAM. Chapter 4 summarises the MARAM structure on a page, with further details available in Appendices 2 and 3.

Chapters 6 to 9 cover the 4 strategic priorities identified to support the changes necessary to implement MARAM. A chapter is dedicated to each strategic priority:

- Clear and consistent leadership (Chapter 6)

- Supporting consistent and collaborative practice (Chapter 7)

- Building workforce capability (Chapter 8)

- Reinforcing good practice and commitment to continuous improvement (Chapter 9)

Each chapter is then subdivided into the work undertaken by Family Safety Victoria as lead in the reforms, departments as lead to their workforces and sector (peak bodies and organisations) to support practitioners.

From 2021–22, Family Safety Victoria is no longer a separate administrative body, but is a division of the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, where work to support Specialist Family Violence Services can now be found.

[1] Further information on legislative MARAM reporting requirements is detailed at Appendix 2.

[2] A full list of program areas with MARAM responsibilities is detailed at Appendix 6.

Chapter 1: List of portfolios reporting

This table sets out the departments, ministers, portfolios and program areas that are referenced in this report.

See Appendix 1 and Appendix 2 for portfolios prescribed in Phase 1 and 2 respectively, and Appendix 6 for a more detailed description of each program area's work profile.

Table 1: Ministers, portfolios and responsibilities for the 2021–22 reporting period

| Minister | Portfolio | Responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

|

The Hon. Ros Spence MP |

Minister for Prevention of Family Violence |

specialist family violence services sexual assault services the Orange Door Network Risk Assessment and Management Panels |

|

The Hon. Ros Spence MP |

Minister for Multicultural |

Organisations that provide settlement or targeted |

|

The Hon. Jaclyn Symes MLC |

Attorney-General |

Magistrates’ Court of Victoria Children’s Court of Victoria Court Network Dispute Settlement Centre of Victoria Aboriginal Justice Group funded programs:

|

|

The Hon. Gabrielle Williams MP |

Minister for Mental |

Mental health Community-managed mental health |

|

The Hon. Anthony Carbines MP |

Minister for Police |

Victoria Police |

|

The Hon. Anthony Carbines MP |

Minister for Crime |

Organisations that provide settlement or targeted |

|

The Hon. Colin Brooks MP |

Minister for Child |

Child Protection Community-based child and family services (including Child FIRST) Registered out-of-home care services (including Secure Welfare Services, care services and Hurstbridge Farm) Refugee Minor program Supported playgroups |

|

The Hon. Colin Brooks MP |

Minister for Disability, |

Forensic Disability Services Multiple Complex Needs Initiative State-funded aged care services |

|

The Hon. Mary-Anne Thomas MP |

Minister for Health |

Hospitals Community Health Services Early Parenting Centres Bush Nursing Centres General practitioners General practice nurses Maternal and child health Alcohol and other drugs |

| The Hon. Mary-Anne Thomas MP | Minister for Ambulance Services |

Ambulance Victoria |

| The Hon. Melissa Horne MP | Minister for Consumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation |

Consumer Affairs Victoria-funded programs:

|

| The Hon. Sonya Kilkenny MP | Minister for Corrections |

Adult Parole Board Community Correctional Services (CCS) Corrections Victoria Justice Health Post Sentence Authority |

| The Hon. Sonya Kilkenny MP | Minister for Youth Justice |

Youth Justice Youth Justice Funded Services Youth Parole Board |

| The Hon. Sonya Kilkenny MP | Minister for Victim Support |

Victims of Crime Helpline Victims Assistance Program |

| The Hon. Danny Pearson MP | Minister for Housing |

Public housing Community housing Homelessness services |

| The Hon. Ingrid Stitt MLC | Minister for Early Childhood and Pre-Prep |

Department of Education Centre-based early childhood education and care services |

| The Hon. Natalie Hutchins MP | Minister for Education |

Department of Education Schools Education services |

Chapter 2: Use of language within this report

Adults, children and young people who have experienced family violence are referred to as victim survivors, noting that some prefer the term

people who experience violence.

The word family has many different meanings. This report uses the definition from the Family Violence Protection Act (the Act), which acknowledges the variety of relationships and structures that can make up a family unit, and the range of ways family violence can be experienced, including through family-like or carer relationships (in non-institutional paid carer environments).

The term family violence reflects the FVPA and includes the wider understanding of the term across all communities. Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families defines family violence as an issue focused on a wide range of physical, emotional, sexual, social, spiritual, cultural, psychological and economic abuses that occur within families, intimate relationships, extended families, kinship networks and communities. It extends to one-on-one fighting, abuse of Indigenous community workers as well as self-harm, injury and suicide.

Throughout this document, the term Aboriginal is used to refer to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Intersectionality describes how systems and structures interact on multiple levels to oppress, create barriers and overlapping forms of discrimination, stigma and power imbalances based on characteristics such as Aboriginality, gender, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, ethnicity, colour, nationality, refugee or asylum seeker background, migration or visa status, language, religion, ability, age, mental health, socioeconomic status, housing status, geographic location, medical record or criminal record. This compounds the risk of experiencing family violence and creates additional barriers for a person to access the help they need.

The term perpetrator describes adults who choose to use family violence, acknowledging the preferred term for some Aboriginal people and communities, as well as in practice, is a person who uses violence.

Adolescents who use family violence require a different response to family violence used by adults, because of their age and the possibility that they are also victim survivors of family violence. The term perpetrator does not refer to adolescents who use family violence.

The Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework is referred to in this report as MARAM.

Chapter 3: Legislation and regulations

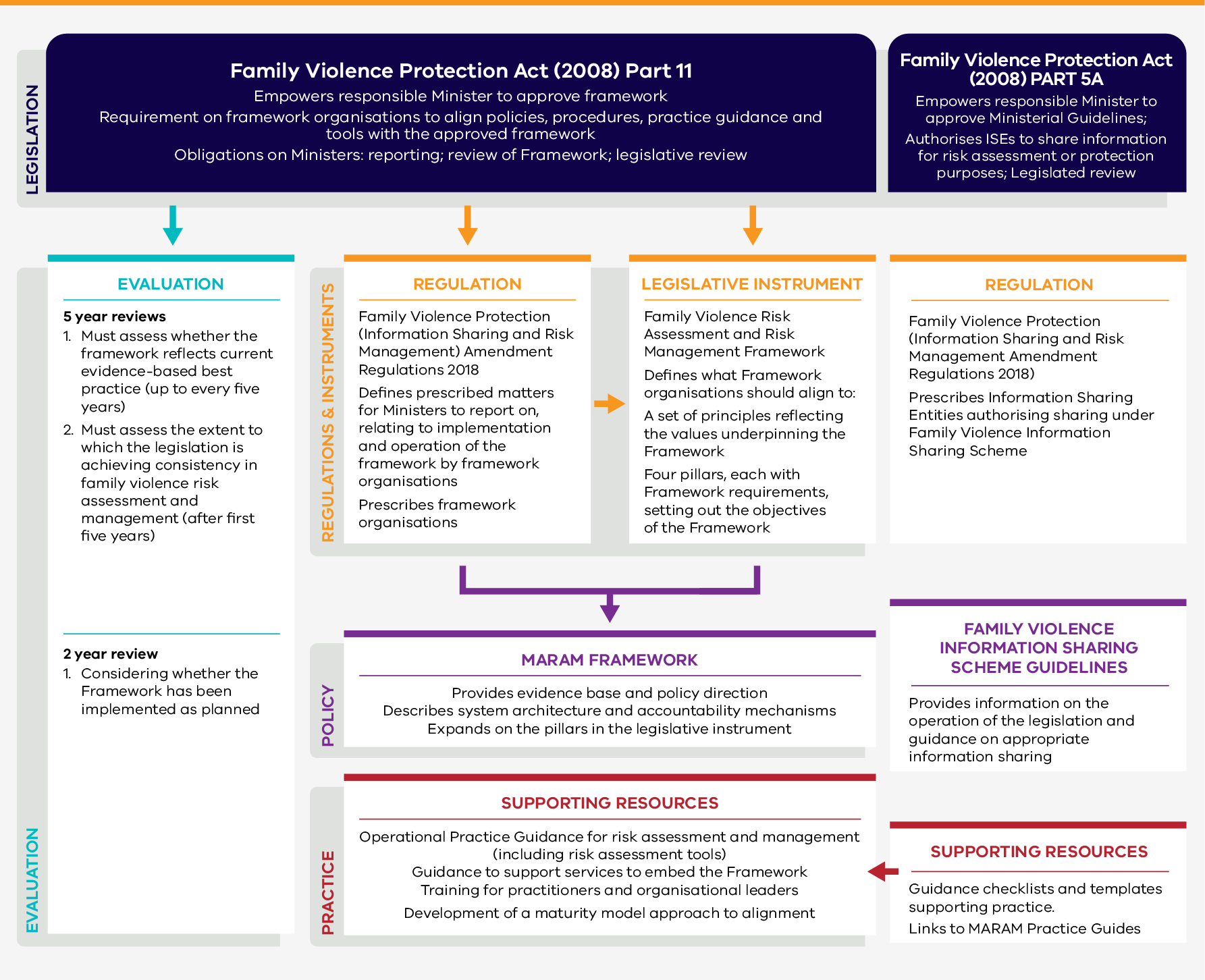

The legislative structure around MARAM is shown in Figure 2.

The top line contains the legislative provisions in the Family Violence Protection Act. Part 11 enables the Minister to approve a framework for family violence response and require framework organisations to align with it. It also establishes formal review and reporting mechanisms. Part 5A of the Act enables the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS).

The second line references the regulations and legislative instruments that operationalise Part 11 and Part 5A of the Act. These name the prescribed workforces and services, and define the core components of the framework and report requirements.

The third line contains the policy documents, namely MARAM and the FVISS Ministerial Guidelines.

The fourth and last line has the supporting resources that put the policy into practice. This includes the MARAM Practice Guides for practitioners, as well as embedding guidance for organisational leaders. This image only highlights the resources produced centrally by Family Safety Victoria as lead agency, and not the many tailored and updated resources applicable to various workforces.

The left side of the image refers to the legislated 5-year evaluations, the first of which will take place in 2022–23. The two-year evaluations were initiated by Family Safety Victoria to guide the implementation activities.

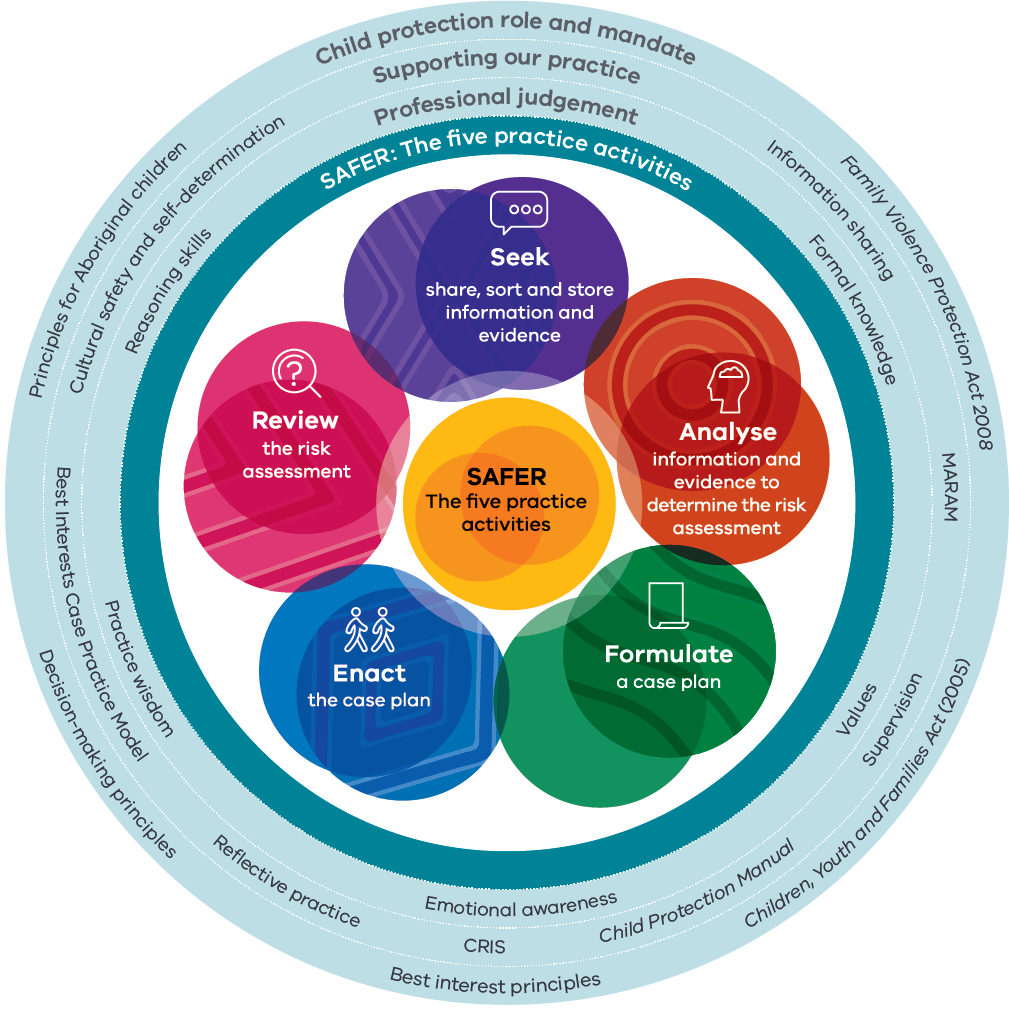

Chapter 4: MARAM structure

The 3 core components of MARAM are illustrated in Figure 3. The MARAM Pillars are set at an organisational level. They each contain a requirement to which organisations must align. Alignment is defined as actions taken by organisations to effectively incorporate the 4 pillars into existing policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools, as appropriate to the roles and functions of the entity and its place in the service system. The MARAM Pillars can be found at Appendix 3.

The MARAM Principles guide a shared understanding of family violence response across the service system to guide consistent practice. The full text of the principles can be found at Appendix 4.

The MARAM Responsibilities set out the practice expectations for workers in relation to family violence risk identification, assessment and management. Organisations determine how the MARAM Responsibilities are met within their workforce. The full details of the responsibilities can be found at Appendix 5.

The responsibilities can be broadly summarised into 3 levels of practice:

- Identification – this role incorporates all MARAM Responsibilities, except those related to assessment and management of risk (3–4 and 7–8). It would apply to people who interact with Victorians in the course of their work, where they could identify family violence is taking place. They may be able to observe family violence narratives or behaviours, and/or ask sensitive questions of victim survivors (for example, at schools and early childhood centres).

- Intermediate – this role incorporates all MARAM Responsibilities, except specialist risk assessment and management (7–8). It would apply to people who interact with Victorians in the course of their work, where they can assess or manage a presenting ‘need’ (for example, alcohol or drug use, mental health or housing crisis).

- Comprehensive – this role incorporates all 10 MARAM Responsibilities. It would apply to people who interact with Victorians in a specialist capacity to directly respond to family violence (for example, Specialist Family Violence Services and refuges).

Chapter 5: MARAM Annual Framework Survey

Family Safety Victoria has committed to undertaking an annual survey of framework organisations to understand:

- the progress of implementation across different sectors

- how sectors can be more effectively supported to implement MARAM and enable continuous improvement.

This reporting period is the second year the survey has been undertaken. It is a voluntary survey targeted to those who have a substantial role in supporting MARAM alignment. For this reason, some workforces may have a limited number of responses as a result of the stage or process applied for implementation.

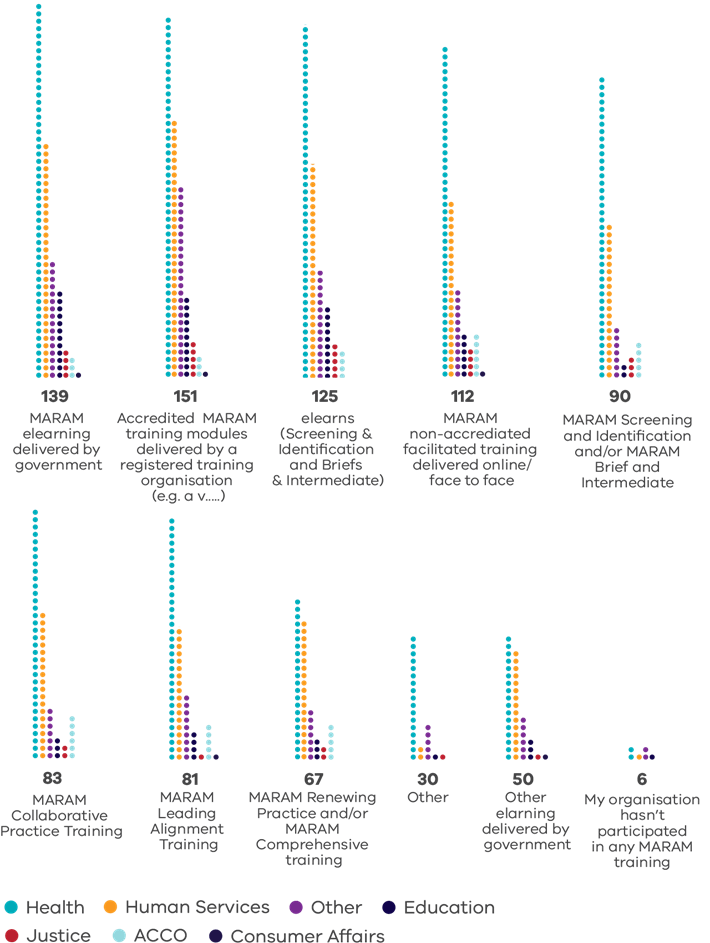

This chapter summarises the results of the survey. It will be referred to at other points in the report where it relates to specific matters, such as training in Chapter 8.

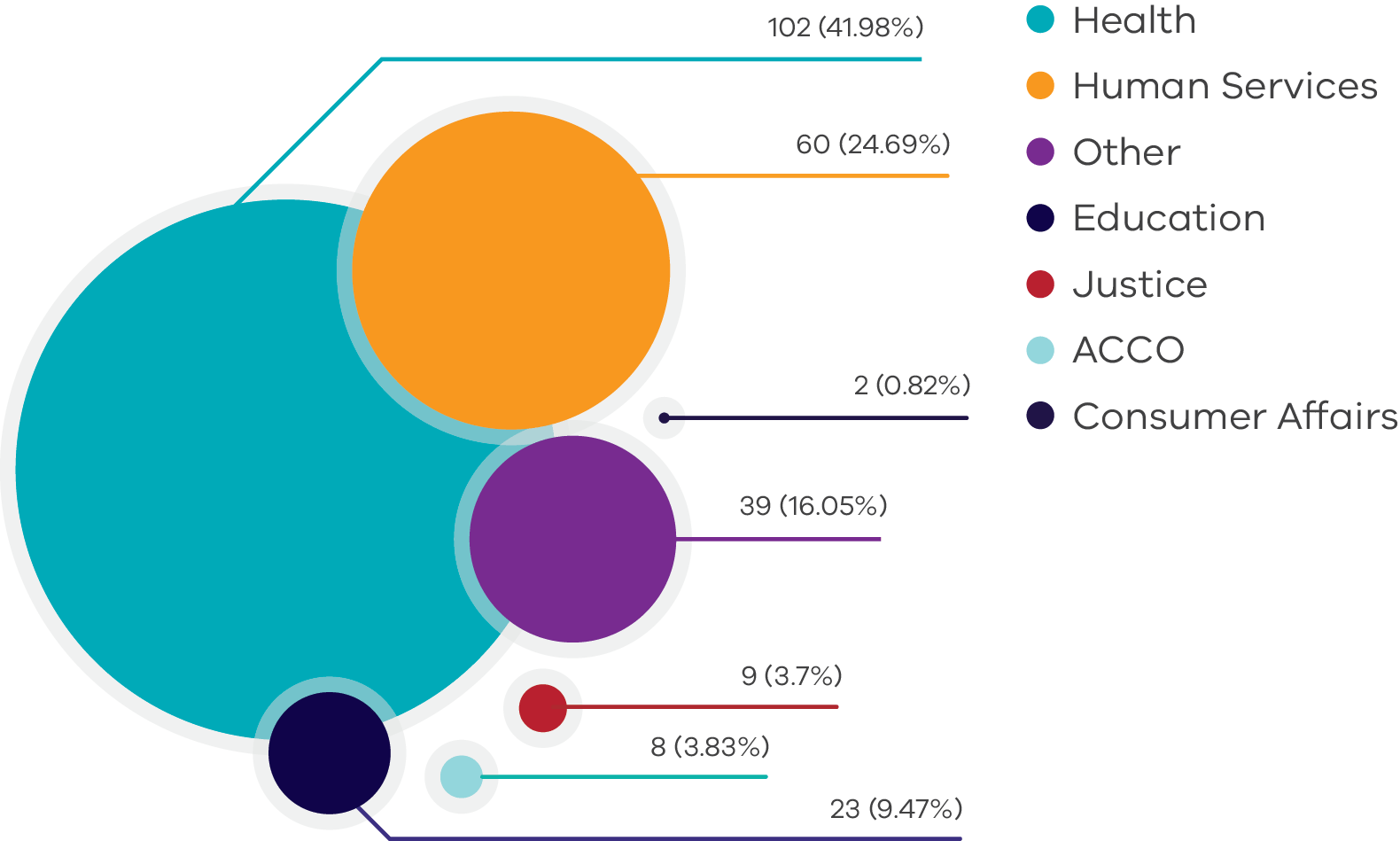

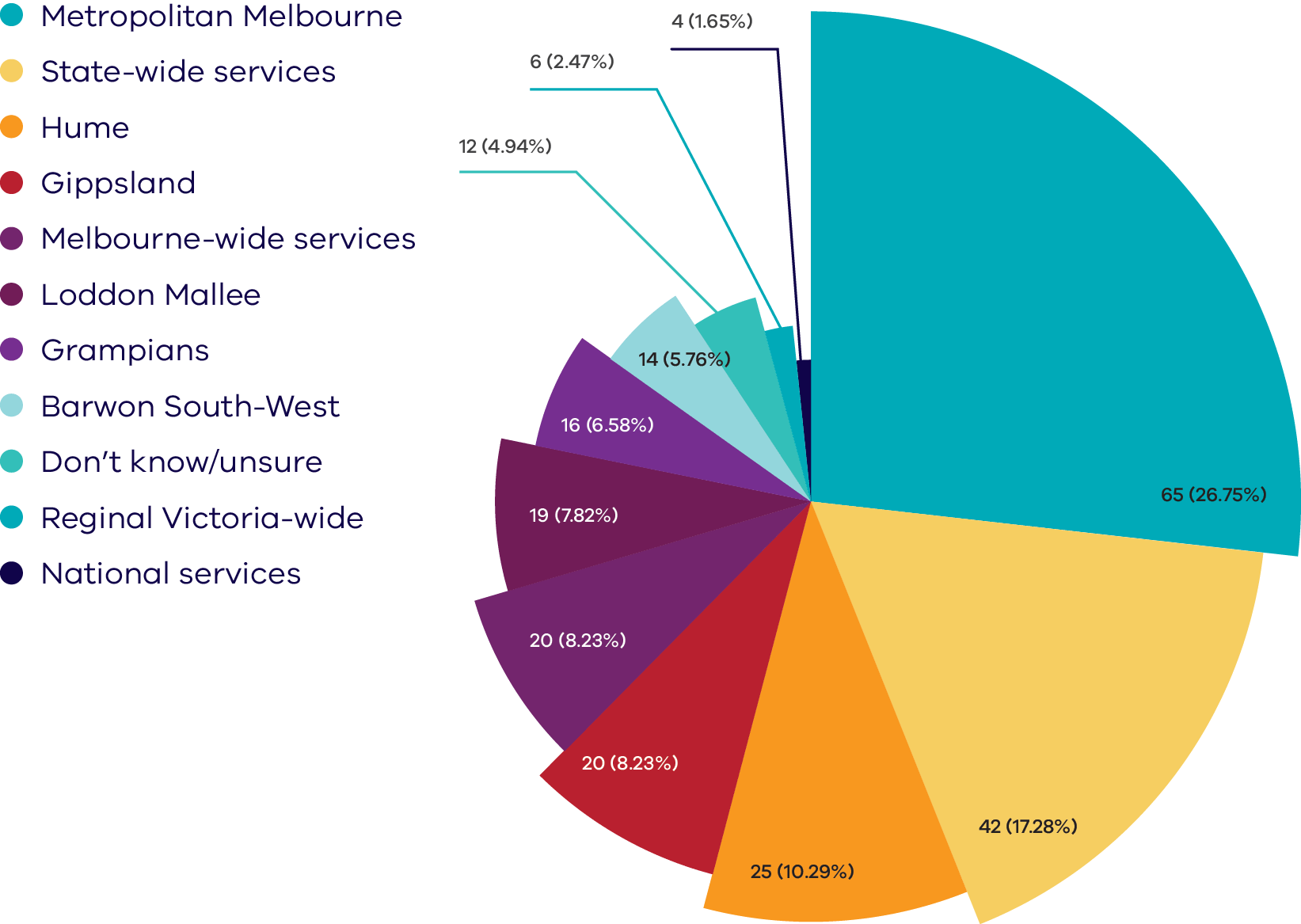

Demographics

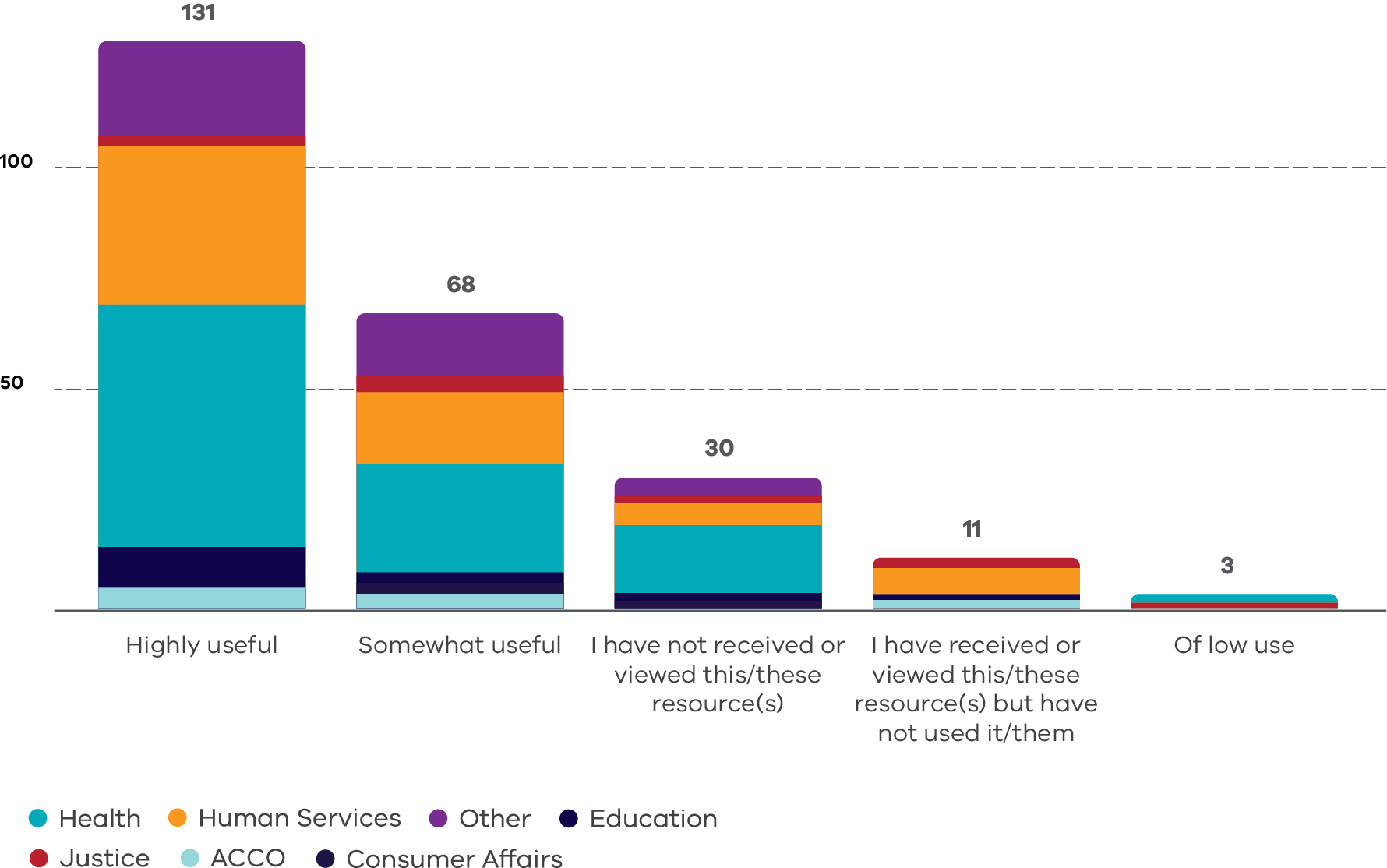

The annual survey captured a total of 243 responses. Most responses (162) were from those employed in large organisations across the health and human services sectors. ‘Other’, with 39 responses, was the third-largest group. This group also mostly represents workers in the broader health and human services sectors. However, these respondents preferred to free text, and one explanation for some could be that they belong to not-for-profit and nongovernment organisations, which did not feel represented in the options provided by the survey.

There was a good spread of responses across metropolitan, regional and statewide services. A further breakdown of data suggests there was a very good representation in the results of public hospitals, community health services, Specialist Family Violence Services, alcohol and other drug services, maternal and child health services, child and family services, and aged care. There was a broad range of responses from other human services, along with some schools, courts and justice areas.

MARAM alignment

In 2020–21, 81 per cent of respondents understood what organisational alignment to MARAM means, 18 per cent understood some aspects, and one per cent did not understand what organisational alignment means.

The results for 2021–22 show that 76 per cent of respondents now understand MARAM alignment, 22 per cent understand some aspects, and 2 per cent (4 respondents) do not understand what organisational alignment means[1]. While this is a slight drop in understanding, it may reflect that the survey was sent to services newly prescribed to MARAM in April 2021 (noting 2 of the 4 respondents were a health service and ‘other’).

In the 2020–21 survey, 85 per cent of respondents identified MARAM alignment as a high priority, and 15 per cent identified it as a medium priority.

In the 2021–22 survey, 77 per cent identify alignment as a high priority, 17 per cent as a medium priority and 5 per cent as a low priority, not a current priority or unsure. The responses in the 5 per cent were primarily made up of health services. This may be indicative of reform fatigue, and the ongoing pressures resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and the continuing impact in health settings.

In the 2020–21 survey, 77 per cent of respondents had a detailed understanding of MARAM Responsibilities for their workforce, 22 per cent had some understanding, and the remaining one per cent had no or limited understanding.

In the 2021–22 survey, 67 per cent of respondents had a detailed understanding of MARAM Responsibilities for their workforce, 32 per cent had some understanding, and one per cent had no understanding. Health services make up the significant portion with some understanding. This, again, may be because health services were only prescribed in 2021, and have been responding to the COVID-19 pandemic as a priority.

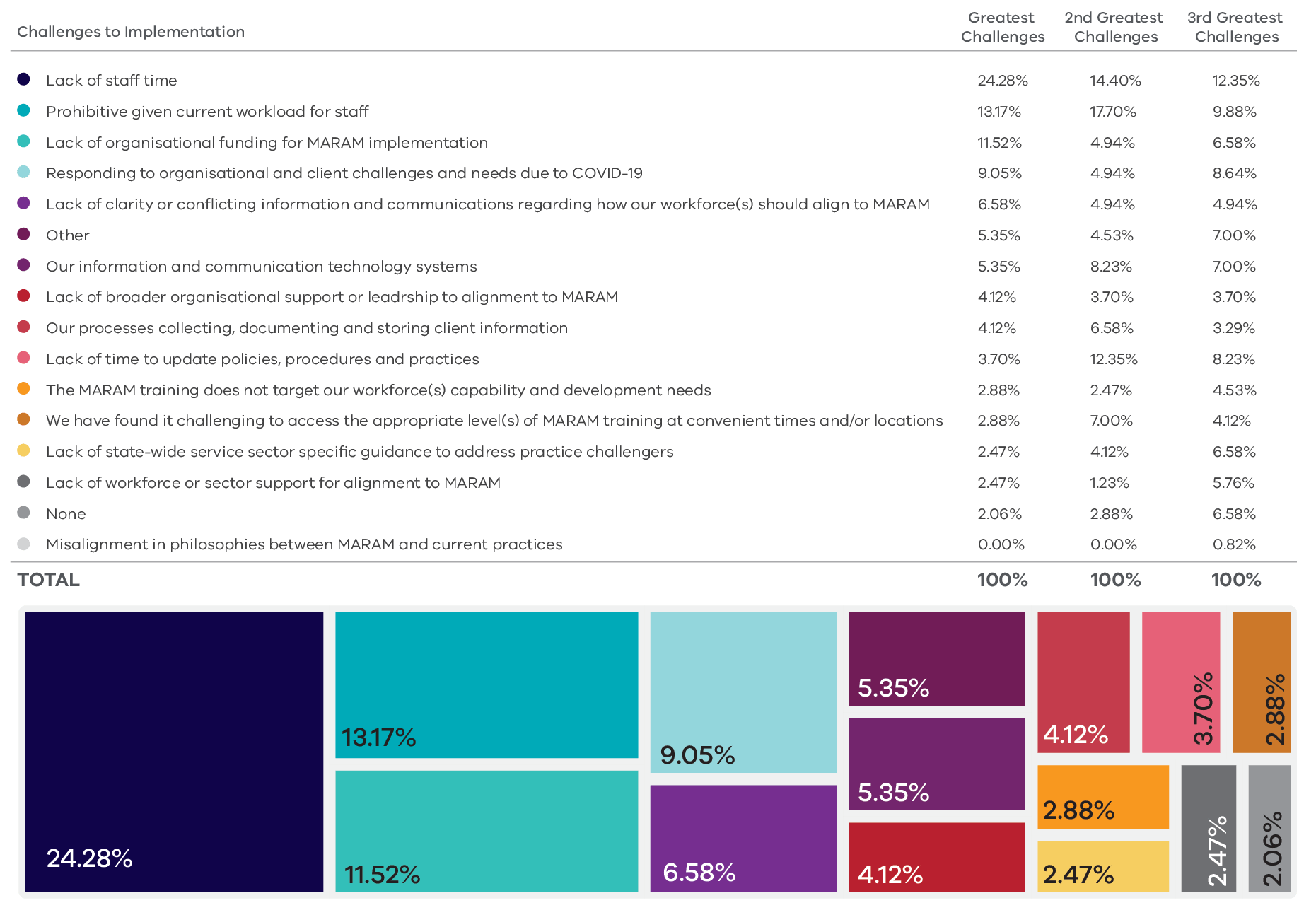

Challenges

In 2020–21, 70 per cent of respondents identified lack of staff time and prohibitive current workload of staff as top challenges to MARAM alignment. For 47 per cent of respondents, lack of organisational funding for MARAM implementation was a challenge.

In 2021–22, the top 3 reasons identified as an implementation challenge continue to be:

- lack of staff time (50 per cent total, 24 per cent as the greatest challenge)

- prohibitive current workload of staff (41 per cent total, 13 per cent as the greatest challenge)

- lack of organisational funding for MARAM implementation (24 per cent total, 12 per cent as the greatest challenge).

It is notable that 23 per cent total recorded that responding to COVID-19 remained a challenge, with 9 per cent rating this as their greatest challenge.

[3] Percentages 0.5 and below are rounded down, 0.6 and above are rounded up.

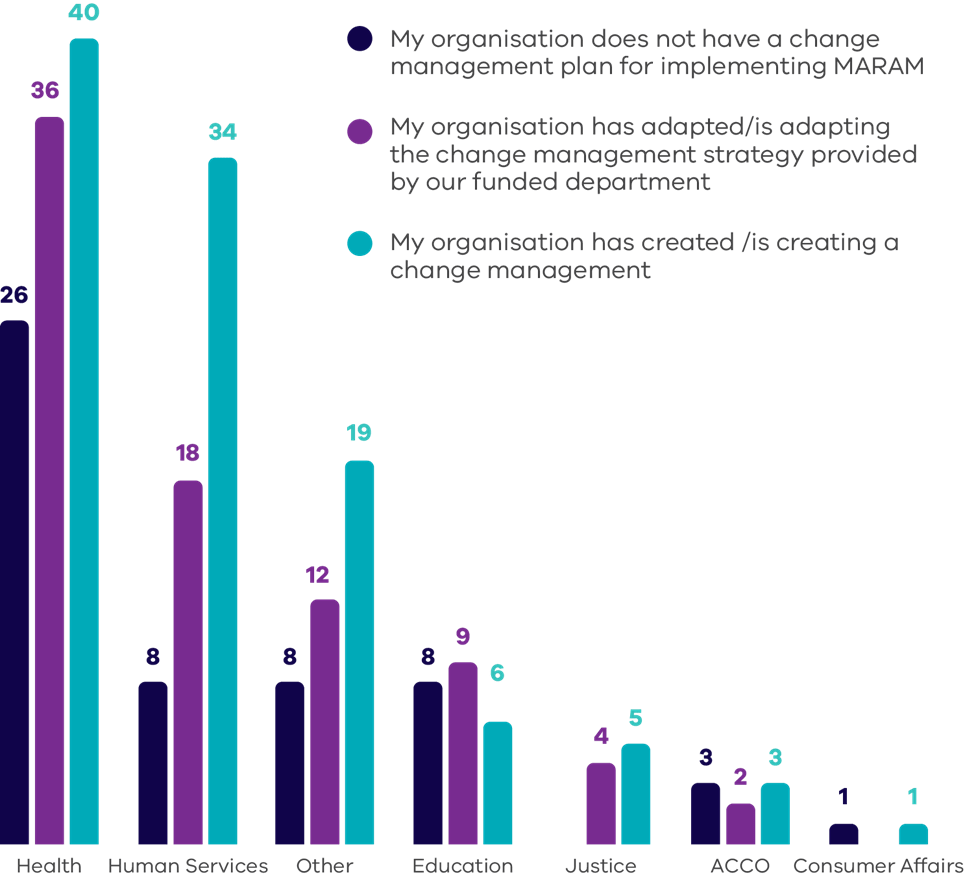

Chapter 6: Clear and consistent leadership

Any reform that requires a change to practice and ways of working relies on strong leadership. Leadership in these reforms requires:

- strategic plans for change management[4]

- governance to monitor and support implementation efforts

- consistent and accurate messaging

- ensuring sector readiness through implementation supports.

Section A: Family Safety Victoria as WoVG lead

Family Safety Victoria demonstrates leadership through coordinating and supporting the work taking place across the government.

MARAM governance for implementation

The Family Violence Reform Board, chaired by Family Safety Victoria, is the strategic leadership body for all family violence reforms, providing oversight and engagement across WoVG reform level issues.

The MARAM and Workforce Directors’ Group oversees the implementation of MARAM and the FVISS scheme. The Directors Group has oversight of budget expenditure, risks and issues of multi-lateral importance, and achievement of milestones and deliverables against agreed project plans.

Supporting these formal governance structures are:

- bilateral meetings between Family Safety Victoria and departments to promote proactive joint management of identified bilateral implementation issues

- manager workshops to discuss any multilateral developments or issues of WoVG relevance at policy level.

This approach provides a platform for strong and effective oversight of MARAM implementation.

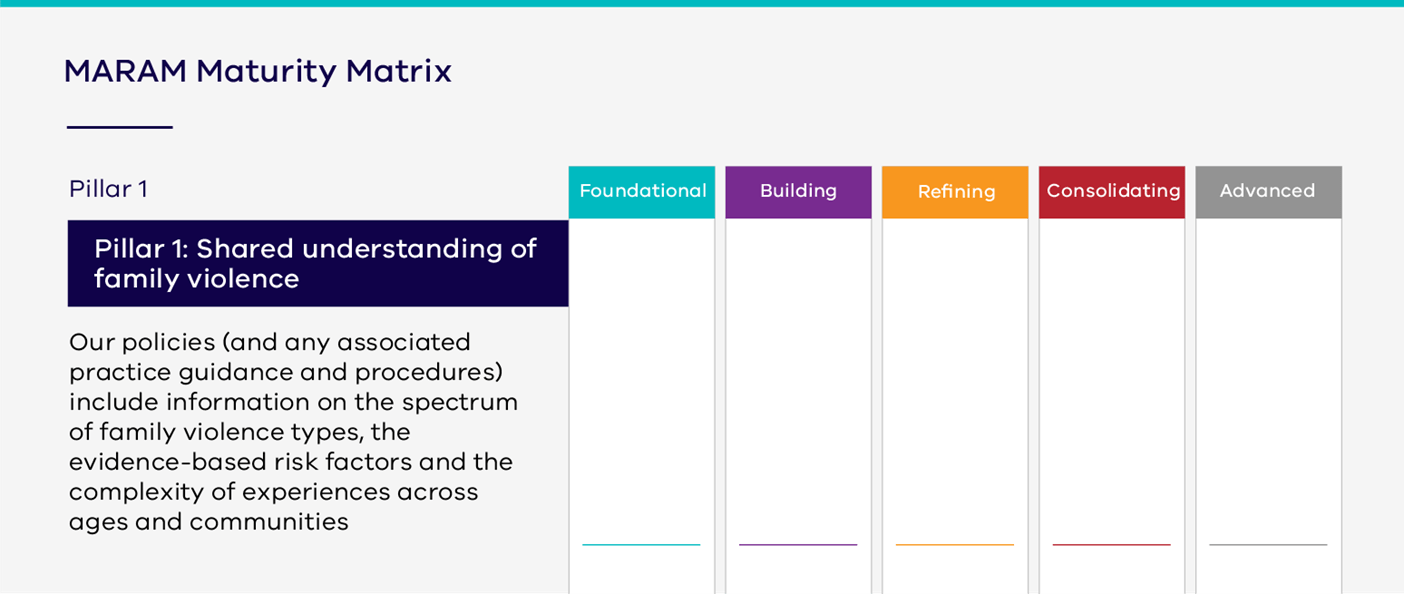

MARAM Maturity Model

The development of a MARAM Maturity Model was initially identified in MARAM as a core product to be developed. Subsequent reviews and evaluations strongly recommended the Maturity Model as a priority piece for implementation[5] [6].

The purpose of the Maturity Model is to provide a common language for organisational improvement through clear alignment milestones. This is achieved by describing the milestones in terms of outcomes, with measurement across a continuum from foundational to advanced.

The continuum will contain examples of each level to help an organisation assess its own progress against an objective scale. There will also be a suite of products to help organisations self-audit and progress in maturity along the continuum.

In progressing the Maturity Model project, Family Safety Victoria is demonstrating a clear commitment to leading reform outcomes. The Maturity Model will set clear standards and expectations for alignment, and large and small organisations will use this to improve their family violence response over time.

Given the complexities that apply to multiple services, it is anticipated that policy development and design for the Maturity Model will continue over 2022–23, with implementation not anticipated to start until 2023–24.

Related strategies, policies and action plans

MARAM sets responsibilities for responding to family violence, but also touches on many other government priorities and aspects of practice.

This includes embedding an intersectional approach in practice, workforce supply and retention, sexual violence and harm, Aboriginal cultural safety and perpetrator accountability. Key policies and government commitments that support and intersectwith MARAM implementation include:

- The Everybody Matters: Inclusion and Equity Statement articulates the Victorian Government’s 10-year vision for an inclusive, safe, responsive and accountable family violence system. Everybody Matters identifies and addresses the barriers that people from a diverse range of communities face when reporting family violence, and seeking and obtaining help. Everybody Matters emphasises the need to address systemic barriers to equitable service delivery and access that is underpinned by the theory of intersectionality.

- A forthcoming 10-year Sexual Violence and Harm Strategy is led by the Department of Justice and Community Safety, in partnership with the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, to improve responses to sexual violence. MARAM will support risk identification and management across all key initiatives in the strategy that intersect with family violence.

- The Building from Strength: 10-year Industry Plan for Family Violence Prevention and Response outlines the Victorian Government’s long-term vision for workforces to prevent and respond to family violence. The building and retention of capable workforces are integral to supporting multi-agency collaborative practice and secondary consultations.

- The Dhelk Dja – Safe Our Way: Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families (Dhelk Dja) agreement is the key Aboriginal-led Victorian agreement. It commits the signatories – Aboriginal communities, Aboriginal services and government – to work together and be accountable for ensuring that Aboriginal women, men, children, young people, Elders, families and communities are stronger, safer, thriving and living free from family violence. It requires the voices of the Aboriginal people across Victoria to be reflected in policy. The three-year action plans are delivered in partnership with the agreement’s signatories.

- The development of the Aboriginal Family Violence Industry Strategy under Dhelk Dja will provide a culturally informed framework to continue to build the capacity of Aboriginal services and its people in the family violence sector. Building on the strong foundations of experience in the sector, it will increase the number of Aboriginal people engaging in further education, prioritise Aboriginal-led family violence programs and prevention initiatives, and highlight the importance of Aboriginal culture in the sector.

[4] The Strategic Priorities of the MARAM Change Management Strategy are outlined at Appendix 7.

[5] The Cube report relates to the ‘Process evaluation of the MARAM reforms’ June 2020 evaluation by the Cube Group, which is not a publicly accessibly report.

[6] Monitoring Victoria’s family violence reforms: Early identification of family violence within universal services, May 2022, Report of the Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor.

Section B: Departments as portfolio leads

Departments demonstrate leadership through the tailored approaches they apply to their workforces, ensuring that the change management process is able to support them.

Department of Education and Training

The Department of Education[7] (formerly the Department of Education and Training) provide leadership and oversight of reform implementation through the Child Safety and Family Violence Project Control Board. The Project Control Board is governed by the Department of Education’s Executive Board as a decision-making body responsible for major project lifecycles (from design to evaluation).

It also manages the strategic direction, coordination and integration of child safety frameworks that include:

- the Child Safe Standards

- the Reportable Conduct Scheme

- information sharing and risk frameworks – the Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS), FVISS and MARAM

- mandatory reporting in early childhood education and care settings, and schools

- criminal offences – a failure to disclose offence and failure to protect offence.

In the reporting period, the Child Safety and Family Violence Project Control Board has approved further targeted MARAM training, tools and reviewed guidance, and the approach to operating MARAM in education and care services.

The MARAM Annual Framework Survey noted that all Department of Education workforces who responded understood what organisational alignment to MARAM means, either in full or some aspects. It also highlighted that all Department of Education workforces who responded identified MARAM alignment as either a high or medium priority.

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing

In 2021–2022, the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing demonstrated clear and consistent leadership through their work on the practice change strategy and in The Orange Door. The inaugural MARAM and Information Sharing week was held from 26 to 29 April 2022. The event was officially opened by the Secretary to the department, Ms Brigid Sunderland and closed by The Hon Gabrielle Williams MP the then Minister for Prevention of Family Violence.

The week comprised 4 webinars of 2 hours each, with a keynote speaker and a panel discussion with experts and people with lived experience of family violence.

The topics were:

- Collaborative practice — sharing information to identify, assess and manage risk to children and families

- Child-centred practice — working with children and young people

- Intersectionality in practice

- Coercive and controlling behaviours and working with people who use violence.

Over 2,000 people registered for the event, with more than 300 people at each session. Attendees were from across the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing workforces, including public housing, community housing, homelessness services, multicultural and settlement services, Child Protection, child and family services, and aged care services.

A highlight was the presentation led by honoured guests, Sue and Lloyd Clarke, founders of the Small Steps for Hannah Foundation and recipients of the 2022 Queensland Australian of the Year award, for their advocacy in raising awareness of coercive control as a form of family violence.

In 2020–21, the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing reported it was developing a MARAM Enabling Practice Change Strategy. This is an internal document to complement formal learning opportunities to apply MARAM practice on a daily basis. The strategy includes a series of behaviour statements to build practitioner confidence and competence in recognising and responding to family violence within the context of their work.

The strategy has now been completed and is used by Department of Families, Fairness and Housing program areas as a resource to retain MARAM consistency when tailoring resources.

The Orange Door network has also demonstrated clear and consistent leadership, as new sites continue to be opened across the state. This includes operationalising the Inclusion Action Plan for The Orange Door, which outlines the baseline and key measures to ensure all users of The Orange Door feel safe, welcomed and respected. There are 18 Aboriginal Cultural Safety Advisors across The Orange Door network, who have been funded to embed the Strengthening Cultural Safety in The Orange Door project. All sites will undertake a Cultural Safety Assessment, and create and implement rolling action plans.

The MARAM Annual Framework Survey notes that all but one human services respondent indicated they understand what organisational alignment to MARAM means, either in full or some aspects. It also highlighted that most human services workforces who responded identified MARAM alignment as either a high or medium priority. However, 12 services identified MARAM alignment as a low priority or were ‘not sure’ of priority, suggesting there is further work required to reach all organisations.

Department of Health

The Department of Health has worked closely with respected health services to provide clear and consistent leadership. In 2021–22, leadership activities have been undertaken with Ambulance Victoria and health services, through the Strengthening Hospital Responses to Family Violence (SHRFV) initiative.

Ambulance Victoria has undertaken a MARAM organisational audit and made key recommendations to drive alignment. It has led briefings on MARAM alignment to Ambulance Victoria leaders, and presented at organisational governance committees, such as the Best Care Committee and the Consumer Advisory Council.

The SHRFV initiative has led alignment across multiple health services through the development of guidance that supports mapping

of MARAM Responsibilities, and aligning policies and procedures.

For community health services, early parenting centres, hospitals and bush nursing centres, the Department of Health has initially focused on delivery of consistent and accurate messaging, to support sector readiness and long-term culture change.

The Department of Health has also demonstrated leadership in response to family violence by prioritising the development of resources to support healthcare workers who are experiencing family violence.

The MARAM Annual Framework Survey notes that health workforces primarily agreed that they understand what organisational alignment to MARAM means, either in full or some aspects. Most health workforces also identified MARAM alignment as a high or medium priority for their organisation. Only 2 health services who responded did not understand what MARAM alignment means.

Out of 102 responses, 9 health services rated MARAM as a low priority, not a current priority or ‘not sure’. As noted above, these results should be interpreted in the context of health services only being prescribed in 2021, and the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health services. It is clearly evident that despite the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the training numbers achieved, and successful embedding of training and establishing collaborative practice and referral pathways, are significant and are a testament to the effectiveness of the SHRFV initiative. These achievements reflect the commitment from Victorian hospitals and health services to embed systems, structures and processes that will identify and respond to family violence.

Department of Justice and Community Safety

The Department of Justice and Community Safety convenes the MARAM and Information Sharing (MARAMIS) Working Group, chaired by the Director of the Family Violence and Mental Health Branch. This working group includes members from across the Department of Justice and Community Safety, including Victim Services, Support and Reform (VSSR), consumer affairs, liquor, gaming and Annual report on the implementation of the Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework 2021–22 25 dispute services, Corrections and Justice Services (CJS), and Youth Justice. The group works collaboratively to support the ongoing reforms and implementation across the department.

CJS has expanded its established family violence governance arrangements by introducing a CJS MARAM Group, in addition to the CJS

Family violence Steering Committee, which holds responsibility of CJS’s MARAM alignment. The CJS MARAM Group provides a platform for information sharing, collaboration and awareness of the work being undertaken on family violence.

The Department of Justice and Community Safety has funded roles across the portfolios to directly support change management. These

include:

- MARAM Sector Support Officers in consumer affairs, liquor, gaming and dispute services, Justice Health, VSSR, the Koori Justice Unit and Youth Justice (which receives extra funding from Family Safety Victoria)

- 2 CJS Family Violence Practice Leads, who have commenced mapping current processes to identify suitable solutions to align to MARAM

- a MARAM Change Manager in CJS.

Three Family Violence Practice Lead roles in the Victims of Crime Helpline play a critical role in building family violence capability and embedding MARAM into practice. The Family Violence Practice Leads also provide subject matter expertise in working with male victims of family violence. The roles provide opportunities to upskill other workforces on how to work safely and effectively with male victims, which include supporting increased capability in predominant aggressor identification.

The MARAM Annual Framework Survey notes that all Department of Justice and Community Safety workforces who responded understand what organisational alignment to MARAM means, either in full or some aspects. It also highlighted that all justice workforces who responded identified MARAM alignment as either a high or medium priority.

The courts

An internal working group was established by the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria (MCV) in 2021, bringing together expertise to plan for the implementation of adults using family violence MARAM responsibilities, practise guidance and tools. This includes mapping of court roles to

each responsibility, tailoring and embedding of tools, and assessing changes to systems, tools, policies and procedures.

MCV has also shown leadership in ensuring that MARAM-aligned practice is embedded within the 7 new Specialist Family Violence Courts. This will support strengthening family violence capability within the MCV. MARAM Annual Framework Survey results are not available for the courts as an entity within the Justice portfolio.

Victoria Police

Victoria Police is a critical workforce to support initiatives that develop and embed practice. This is particularly the case with working with persons who use family violence.

In consultation with the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, and Family Safety Victoria, Victoria Police led the development of a strategic intelligence assessment to examine the incidence and numbers of youth issued with a Family

Violence Intervention Order.

The assessment was delivered in August 2021 to assist the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing understand the number of youths that may require crisis accommodation. Key findings from the intelligence assessment and stakeholder engagement indicated that police would also benefit from the development of specific practice guidance.

As a result, the internal practice guidance, Responding to Adolescent Family Violence, was published in January 2022. The guidance promotes consideration of early childhood experiences of trauma, confirmation of emergency accommodation, and the support of cautions and diversions, to avoid further contact with the justice system for young people.

A project has also been established in Family Violence Command to refine Victoria Police policy and progress activity regarding predominant aggressor identification, to reduce the occurrence and impact of misidentification by police.

This work will be completed in conjunction with the outcomes of the Misidentification Predominant Aggressor Working Group. This Working Group, led by the Department of Justice and Community Safety, brings together Victoria Police, MCV and legal services, Child Protection and support services.

The Working Group addresses issues such as:

- supporting and providing training to police officers to identify the predominant aggressor before commencing a risk assessment, and before it is committed to the Law Enforcement Assistance Program crime database

- reviewing how family violence records are captured in the Law Enforcement Assistance Program crime database to ensure that when misidentification has occurred, remedial action is taken to resolve the issue

- developing a clear process for an urgent return to court in matters where misidentification has occurred

- working with other services, such as Child Protection and The Orange Door, to deliver greater clarity on reporting concerns and providing support, and to ensure that when they do address protective concerns, perpetrators are also held to account.

- MARAM Annual Framework Survey results are not available for the Victoria Police as an entity within the Justice portfolio.

[7] The Department of Education and Training was renamed The Department of Education in January 2023 following Machinery of Government change.

Section C: Sectors as lead

Funded sector capacity-building participants have consistently demonstrated leadership in embedding the reforms within their workforces.

Some highlights include:

- The Council to Homeless Persons has developed a Specialist Homelessness Sector Learning Hub to demonstrate an evidence based, shared understanding of family violence risk and impact. The Learning Hub is a central place to host useful MARAMIS learning products and resources that are relevant to the homelessness services sector.

- The CFECFW developed and released an Emerging Themes video series that explores common themes across MARAM, FVISS and CISS for all workforces. The videos support MARAM learning across the sector and can be embedded into an organisation’s own learning and development system. They also provide clear and consistent leadership on recognising children as victim survivors of family violence, and safe and effective engagement with young people.

- Court Network is a community organisation providing non-legal information, referral and support to court users via telephone, online and in court. Court Network provides trained volunteers in all Victorian court jurisdictions and at 28 courts. Court Network empowers and increases the confidence of court users to manage their court matters through before, during and post-court options for engagement. It developed the Court Network Volunteer Family Violence Practice Guide to provide consistent messaging and leadership to volunteers.

- VAADA produces a monthly newsletter as part of its communications strategy. This is sent to alcohol and other drug workforces and includes items that are specifically related to MARAM. It also promotes the availability of MARAM training and Family Safety Victoria updates, as well as news from the broader family violence sector. The first newsletter received close to a 40 per cent click-to-open rate, which is far above the industry standard of around 26 per cent.

- Jewish Care delivered a series of E-bulletins consisting of 27 resources to prescribed organisations. The E-bulletins included resources to clarify the requirements of phase 2 organisations to align to MARAM, support organisational leaders to align to the MARAM Pillars, and to support workers who are new to family violence to embed MARAM tools into their practice.

- Dardi Munwurro completed a workforce mapping exercise across all programs and services, to determine the MARAM Responsibilities that are applicable to its staff. There are 95 per cent of Dardi Munwurro staff who now understand the requirements needed to align their practice to the MARAM framework.

The Orange Door

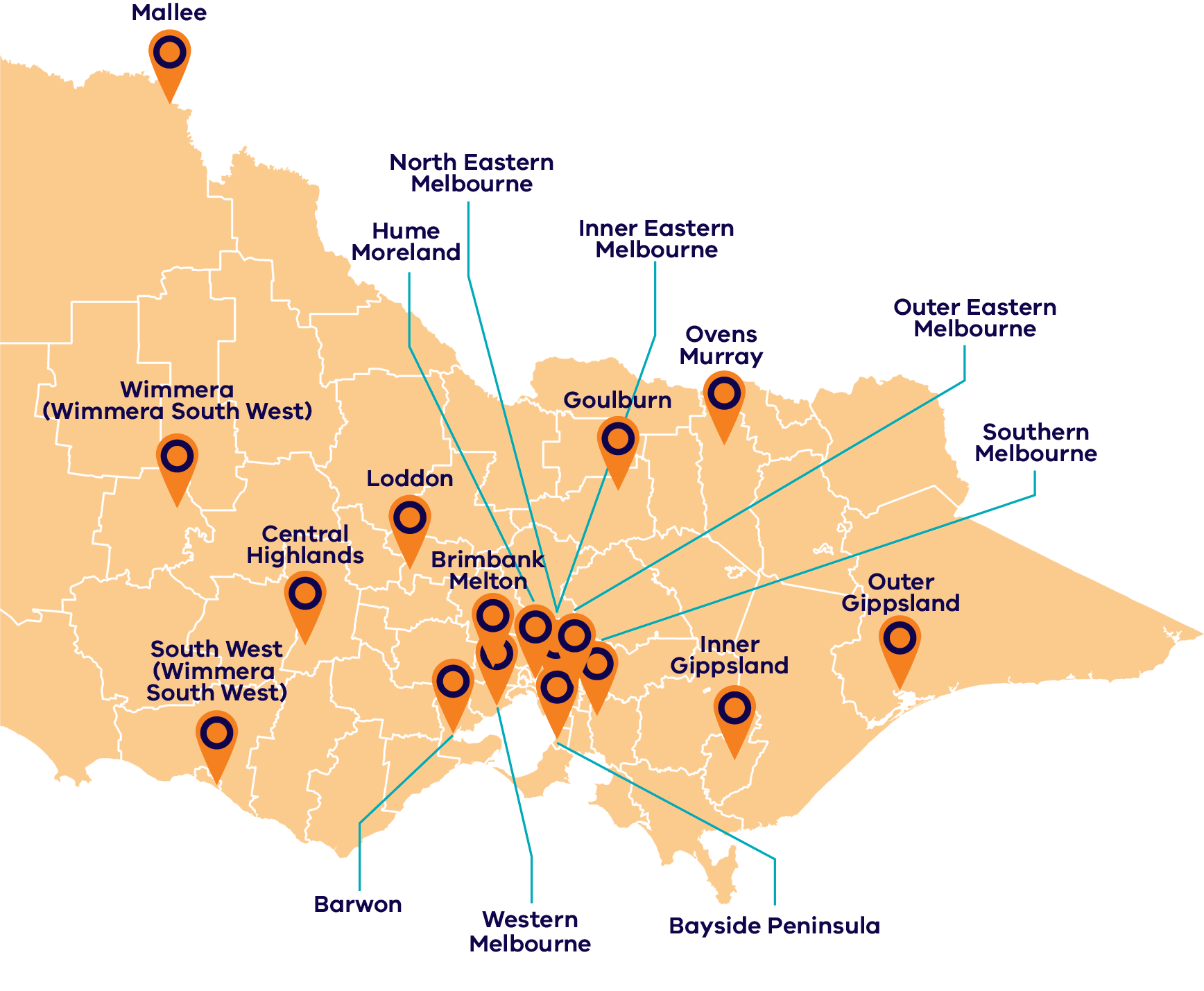

The Orange Door network was established in response to Recommendation 37 of the Royal Commission for ‘a single, area-based and highly visible intake point’ to be available in each Department of Families, Fairness and Housing region.

The Orange Door is a free service for adults, children and young people who are experiencing or have experienced family violence, and families needing support with their wellbeing and development of their children. It assesses and responds to a person’s immediate needs and risk, and connects people to family violence services, ACCOs, family services and services for people using violence.

The Orange Door network provides coordinated support, including crisis assistance and support, risk and need assessments, and safety planning, as well as supporting people to connect to other services for longer-term support.

In 2021–22, The Orange Door network finalised the statewide rollout, so that no matter where people experiencing family violence live, they can now access support through The Orange Door network.

Operational guidance for The Orange Door is developed in consultation with key stakeholders, including MARAM and Practice Development teams in Family Safety Victoria, to ensure the guidance is aligned to MARAM.

Since its inception in 2018, The Orange Door network has assisted more than 238,000 people, including 95,000 children statewide. It has also completed 82,051 risk assessments and safety plans. This is a clear example of the outcomes that can be achieved with clear leadership.

| Case Study: The Orange Door |

|---|

|

The Bandara family attended The Orange Door seeking financial assistance to buy food and other items. Dayani* and Fernando* were unable to access income support as they were seeking asylum in Australia. The family was being supported by a number of agencies, including health and culturally specific organisations. Dayani shared a recent family violence incident resulting in Fernando being served with a limited intervention order, with conditions. Dayani wished to remain in the relationship and the family home, and was concerned for Fernando’s wellbeing. The Orange Door practitioner undertook a MARAM risk assessment and went through a MARAM safety plan with Dayani, which included advising her of support options, as well as strategies in the event of family violence continuing. Dayani declined family violence support, as she was satisfied with the therapeutic support she was receiving from her culturally specific organisation. With Dayani’s consent, The Orange Door contacted the organisation and shared Dayani’s MARAM safety plan and The Orange Door’s MARAM family violence assessment. During Fernando’s assessment, he discussed his use of violence, lack of employment, depression and substance misuse. He acknowledged his values and belief systems had shaped his choice to use violence. The practitioner referred Fernando to a culturally specific Men’s Behaviour Change Program specialising in cultural values and issues relating to migration that may be contributing factors to family violence risk. Fernando also agreed to engage in a drug and alcohol service. The Orange Door practitioner and Fernando contacted the service together, and completed a preliminary assessment and arranged a follow-up appointment in 2 days. The Family Services worker undertook to coordinate a case conference with the professionals involved after their home visit, and continued to monitor and assess the family violence risk. Note: Risk assessments and safety plans would also be undertaken on the children’s experience of family violence. *Not their real names. |

| Case Study: Safe Steps |

|---|

|

Tanya* called Safe Steps on a Sunday afternoon while her partner and her children were away from home. She was not sure why she called Safe Steps, describing herself as in an ‘ok’ marriage with fights time to time like ‘most normal relationships’. The crisis response worker identified some common indicators of trauma based on using her professional judgement. Minimising risk to safety is a common response of victim survivors. Tanya agreed to participate in a discussion to inform a MARAM risk assessment. The assessment identified a range of serious risk factors and determined Tanya’s risk level at ‘serious risk’. This included physical harm, sexual assault, controlling behaviours and financial abuse. Tanya was being prevented from training to return to the workforce, as well as access to the doctor. Tanya decided to stay in her relationship for the time being. Using the MARAM risk assessment tool helped Tanya understand that what she was experiencing was family violence and enabled her to take steps to engage in safety planning. Tanya was supported to understand that help is available if she needs to leave the relationship or if risk escalates and she needs support for her safety. Note: Risk assessments and safety plans would also be undertaken on the children’s experience of family violence. Information would be sought about the perpetrator to understand other risk factors present. Referral to therapeutic supports for Tanya and children would be supported. *Not their real names. |

The Safe Steps case study demonstrates the use of:

- a MARAM Risk Assessment

- MARAM Safety Plans

- respect for the victim survivor’s agency

- trauma-informed practice

- the use of structured professional judgement.

Summary of progress

Family Safety Victoria, government departments and the sector are working hard to communicate the intent and impact of the reforms to workforces, and to create systems for feedback and continuous improvement.

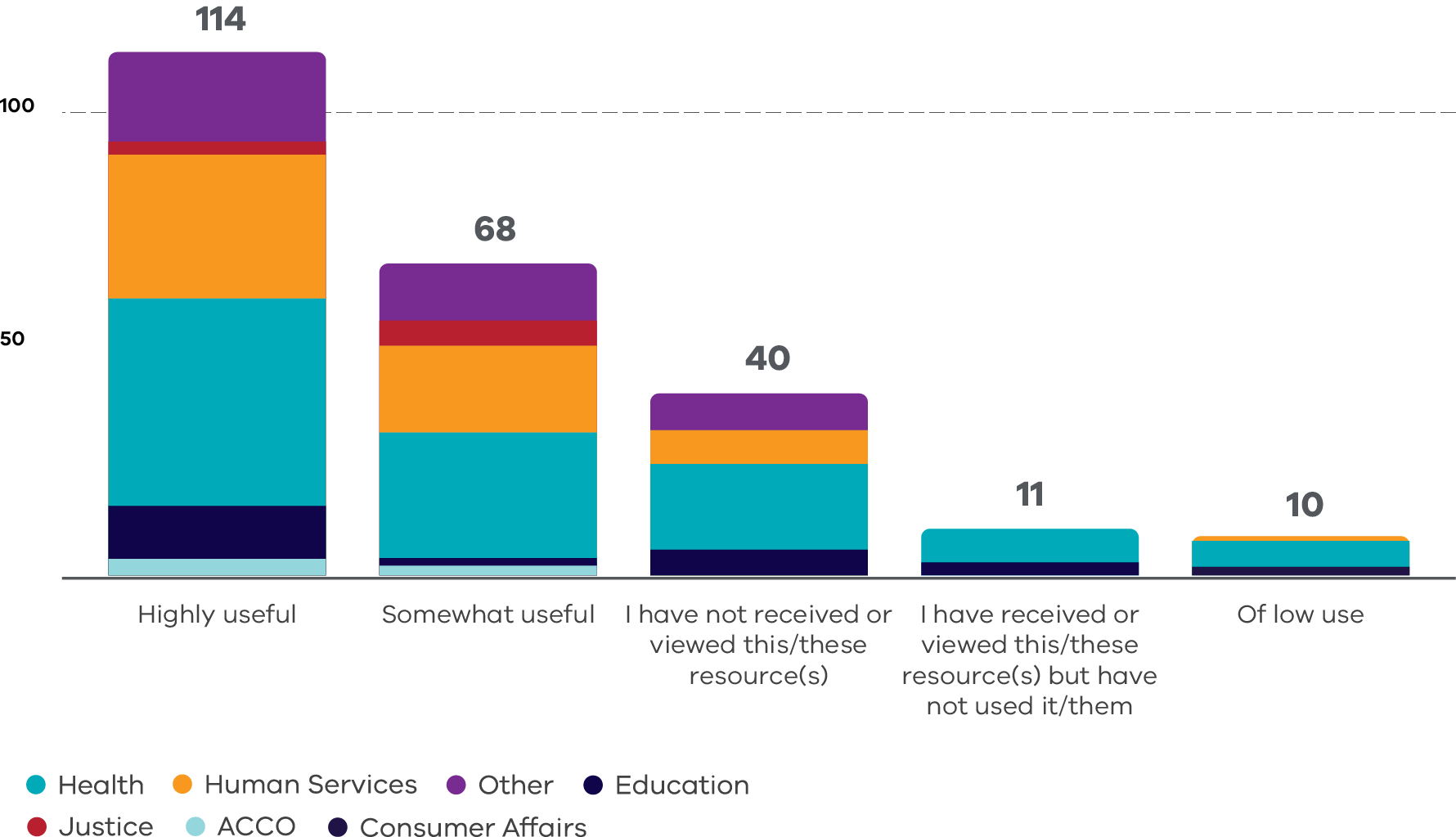

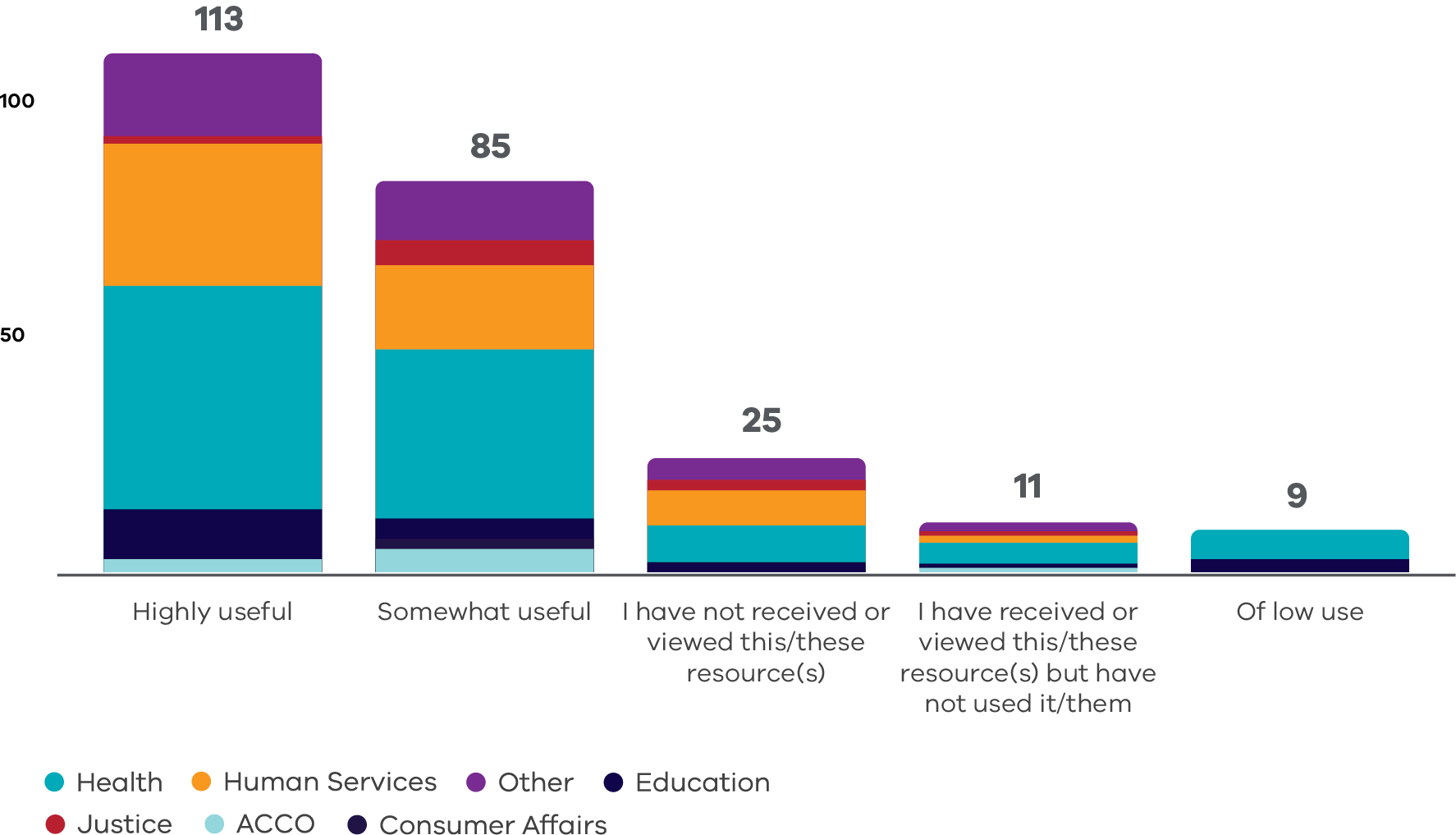

The MARAM Annual Framework Survey results confirm that:

- 74 per cent found Family Safety Victoria communications and information highly or somewhat useful

- 81 per cent found department communications and information highly or somewhat useful

- 82 per cent found peak body communications and information highly or somewhat useful

- 73 per cent found management communications and information highly or somewhat useful.

This suggests that there is some room for improvement in how messaging is reaching workforces, and to determine what communications and information are the most effective. There are limited mechanisms for drilling down further into this feedback, but opportunities to engage with workforces will be considered.

Chapter 7: Supporting consistent and collaborative practice

One objective of MARAM is to ensure its consistent use across prescribed organisations[8] and services. Pillar 2 expands on this to require organisations to have a ‘shared approach to identification, screening, assessment and management of family violence risk’. This is achieved using tools consistent with the MARAM evidence-based risk factors.

Consistent practice does not require using the MARAM practice guidance and tools in their original form. This would not allow for the nuance across multiple services and practices. Instead, it requires services in education, health, justice and community to base their practice on MARAM practice guidance and tools. The purpose is so that family violence risk is assessed and managed on the same understanding and evidence base, no matter the service engaged with.

Consistency also improves collaboration, as services are able to use the same language and understanding of family violence risk to work together to keep victim survivors safe and perpetrators accountable.

Family Safety Victoria creates centralised, evidence-based resources that are shared with departments and sectors to tailor and embed into their workforces.

This chapter summarises the work of:

- Family Safety Victoria to continue to develop centralised resources required to support MARAM

- departments to interpret and tailor the centralised resources into workforce operational contexts

- sector peak bodies to bring the practice to life directly with practitioners.

[8] A full list of MARAM prescribed organisations is provided at Appendix 1.

Section A: Family Safety Victoria as WoVG lead

MARAM Practice Guides and Tools

The adult perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides and tools were developed throughout 2020 to 2022, in partnership with NTV. The guides and tools were released in July 2021 for non-specialist workforces, and in February 2022 for specialist workforces.

The guides draw on a range of evidence and best-practice models available across Australia and internationally. Over 1,000 professionals were extensively consulted to develop the guides.

The perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides and tools include guidance on broad-ranging areas of practice. They promote victim-centred practice, an intersectional and a trauma-and-violence-informed lens, and an understanding and assessment for coercive control, across types of relationships, identities and community groups[9].

Guidance and a tool are also included to support the accurate identification of the predominant aggressor/perpetrator. This is the first misidentification tool developed for statewide use in Australia. Accurate identification of the perpetrator of family violence is a critical component of risk assessment and risk management.

The MARAM Practice Guides highlight the use of systems abuse and provide professionals with guidance on identifying and mitigating any immediate and long-term impacts caused by misidentification or system errors.

The misidentification guidance and tool were developed in consultation with Victoria Police, the Magistrates’ Court, Victims of Crime Helpline, Child Protection, NTV, Safe and Equal, the Victim Survivor Advisory Council[10]. Professionals working with Aboriginal and diverse communities also contributed to the tool and guidance development.

Increased use of MARAM online tools in specialist services

Tools For Risk Assessment and Management (TRAM)[11], The Orange Door Client Relationship Management System (CRM)[12] and the Specialist Homelessness Information Platform (SHIP)[13] are the online data systems that provide access to MARAM tools for use by practitioners to conduct risk assessments and safety plans. They are primarily used by Specialist Family Violence Services and homelessness services. Their availability is being extended to new organisations to support consistent use of MARAM tools across these services.

The continued year-on-year increases suggest numerous contributing factors, such as:

- the increasing number of The Orange Door sites opening across Victoria

- caseloads

- the number of on-ground practitioners

- greater risk assessment and management confidence

- an increase in the number of services conducting the assessments.

[9] As outlined in the MARAM Foundation Knowledge Guide, coercive control is a pattern of behaviours, including emotional, financial, controlling, sexual and physical violence. The behaviour is intended to harm, punish, frighten, dominate, isolate, degrade, monitor or stalk, regulate or subordinate the victim survivor.

[10] The Victim Survivor Advisory Council was formed in July 2016 to give people with lived experience of family violence a voice, and to ensure they are consulted in the family violence reform program. Members are appointed by the Minister for Prevention of Family Violence.

[11] TRAM: Tools for Risk Assessment and Management are used by practitioners in The Orange Door for risk assessment, and a select number of specialist family violence agencies for risk assessment and safety planning.

[12] CRM: Client Relationship Management system is used by practitioners in The Orange Door for safety planning.

[13] SHIP: Specialist Homelessness Information Platform is used by specialist family violence and homelessness services for risk assessment and safety planning.

Section B: Departments as portfolio leads

Department of Education

To support the development of consistent practice, the Department of Education developed an information-sharing and family violence reforms toolkit and guidance. The toolkit sits alongside and complements training and eLearning modules (see Chapter 8) provided to centre-based early childhood education and care services, schools, system and statutory bodies, education health, wellbeing and inclusion workforces, and Department of Education corporate workforces.

The toolkit contains templates, checklists and materials that can be adapted to meet the needs of the school, service or organisation. The guidance has been developed to provide general information and support for education and care workforces that are authorised to use the reforms. The toolkit and guidance support the legally binding Ministerial Guidelines for CISS and FVISS. Hard-copy versions of the toolkit were mailed out to all centre-based early childhood education and care services, and schools in Terms 3 and 4, 2021.

Family Safety Victoria and the Department of Education also provided Early Childhood Australia (ECA) with funding to scope the family violence identification and response needs of the centre-based early childhood sector to align with MARAM and capability frameworks. ECA also developed a MARAM toolkit, including tools, resources, policies, procedures and guidance to support MARAM alignment and workforce capacity building, and to complement the Department of Education’s information-sharing and family violence reforms guidance.

The ECA toolkit was piloted in 5 early childhood services. Before piloting commenced, the 5 pilot services were surveyed in 2021 to understand how confident staff were to identify and respond to family violence, what policies, procedures and training were being used, and what support staff had to identify and respond to family violence.

The Department of Education continues to support all Victorian Respectful Relationships schools to implement and embed Respectful Relationships, which is a primary prevention of family violence initiative. It supports schools to promote and model respect, positive attitudes and behaviours, and teaches students how to build healthy relationships, resilience and confidence. As at 30 June 2022, a total of 1,951 Victorian government, Catholic and independent schools are signed on to the Respectful Relationships initiative.

The Department of Education’s Respectful Relationships area staff provide on-the-ground support to schools, including Project Leads to guide implementation and Liaison Officers to support schools to identify and respond to disclosures of family violence, and to implement FVISS and MARAM. The Department of Education engaged Safe and Equal to update the Identifying and Responding to Disclosures of Family Violence training for the Department of Education’s Respectful Relationships workforce, to align with CISS, FVISS and MARAM (see Chapter 8).

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing

With responsibility for multiple workforces prescribed under MARAM, the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing has continued to review the frameworks, guidelines and tools that are required to be updated, to align to MARAM to support consistent and collaborative practice.

The progress made in 2021–22 included:

- The Service Provision Framework: Complex Needs sets out the service model, operational processes and decision-making points for the development and implementation of 2 complex needs services – the Multiple and Complex Needs Initiative (MACNI) and Support for High-Risk Tenancies. These services are delivered collaboratively by government, ACCOs, and health and community service organisations. This workforce holds identification of MARAM Responsibilities, and the updates made to the Service Provision Framework supports MARAM-aligned practice.

- The SAFER children framework is a risk assessment and management framework to support the work of child protection practitioners. Work was undertaken to align the SAFER children framework to MARAM, and it was launched in November 2021. As part of the alignment, MARAM risk assessment tools have been built into the Client Relationship Information System used by practitioners as part of the overall SAFER risk assessment. The outcome is that the combined tools deliver greater visibility of the intersecting risks of family violence, and support a consistent response when family violence is identified.

- MARAM Operational Guidelines for Public Housing Staff provide for the application of victim-survivor-focused MARAM practice across public housing operations. The finalisation of the guidelines was highlighted as a Department of Families, Fairness and Housing priority in the 2020–21 annual report. The guidelines set out key principles and pillars that should be embedded into procedures, service delivery and practice. They describe a shared responsibility between prescribed services and sectors to identify and respond to family violence. The aim is to build a consistent and collaborative practice by outlining MARAM practice requirements, including:

- MARAM Responsibilities

- a process for when family violence is suspected or disclosed

- basic safety planning

- information sharing

- tools to support identification and safety planning.

- The Homelessness Services Guidelines and Conditions of Funding 2014 document sets out the requirements for delivering state-funded homelessness services, particularly the essential pre-requisites that must be delivered to meet service agreement obligations. An initial MARAM updated has been included in the COVID-19 amendment to require organisational leaders to determine which MARAM Responsibilities apply to their organisations. Revised Homelessness Services Guidelines are intended to be published in 2023, which will include further content to support MARAM alignment.

- Family Safety Victoria completed significant work in 2021–22 to update the Risk Assessment and Management Panel (RAMP) Operational Requirements to ensure MARAM alignment. The requirements outline the responsibilities of RAMP Core Members under MARAM and the FVISS and CISS Schemes, and ensure consistent application across the network. The updated requirements situate RAMP’s approach to risk assessment and management to align to the MARAM framework, and extensively reference the MARAM Practice Guides, templates and tools.

- The expansion of the Central Information Point (CIP) to RAMPs was undertaken as a phased rollout from 2020, which was completed within the 2021–22 financial year. RAMP access to the CIP is part of the Royal Commission’s recommendation to establish the CIP[14]. RAMP coordinators who have completed CIP training have provided consistent feedback on the positive impact of the CIP expansion, and that it supports a consistent and collaborative approach to responding to high-risk cases.

Department of Health

A dedicated team within the Department of Health is responsible for supporting program areas and peak bodies to identify and update policies and guidelines. In 2021–22, achievements to support consistent and collaborative practice included:

- Mental Health and Alcohol and Other Drugs – Approximately 40 Specialist family violence advisors are established in each of the 17 department areas to support alcohol and other drug and mental health services. The Department of Health led the revision of the Specialist Family Violence Advisor guidelines, which outline specific responsibilities on MARAM implementation.

- Hospitals – In May 2022, SHRFV released a new resource to support hospitals to undertake workforce mapping for working with adults who use family violence.

- Ambulance services – Ambulance Victoria has developed a range of tailored family violence resources, and taken actions to support consistent and collaborative practice, including:

- contextualisation of the MARAM Brief Assessment Tool for use by paramedics in home and community settings

- working closely with The Orange Door to support effective statewide referrals and information sharing, as well as supporting paramedics to make consistent referrals to patients when not transported

- development and implementation of systems and day-to-day operations to support the FVISS and CISS

- audit of electronic patient record software capabilities against MARAM requirements with recommendations for technical changes required.

- Health workforces – the Department of Health has developed resources for all health services to support healthcare workers who are experiencing family violence. This includes a guide to developing a family violence and workforce policy, and a guide to managers on how to support staff.

Department of Justice and Community Safety

Throughout 2021–22, the Department of Justice and Community Safety continued to update policies, procedures, and practice guidance to support a broad range of workforces, including:

- CJS has been able to progress several actions to build consistent and collaborative practice, such as:

- content from the Managing Family Violence in Community Corrections Services Practice Guideline that has been merged into other existing practice guidelines, which reflects a move to family violence being ‘business as usual’. There are now family violence processes embedded across 17 practice guidelines in addition to a standalone document

- the Managing Family Violence Incidents in Prisons Guideline has been amended to include The Orange Door as a resource option and updated references to specific family violence offences.

- the CJS Family Violence Flag Project aims to improve the identification of victim survivors and persons using family violence in the CJS information management systems. In this reporting period, the information technology (IT) solution has been designed and approved, and work has progressed towards commencement of the build of the IT solution.

- the Women’s Prison System is assessing all operational policies and procedures to embed a trauma-informed approach. To date, 24 Local Operation Procedures have been reviewed using the Trauma Impact Assessment.

- Justice Health has developed a new resource to support FVISS and CISS awareness within its Information Sharing Entities and Risk Assessment Entities, which includes health information-sharing processes and how to access Justice Health services. This has resulted in a 61 per cent increase in requests for information under FVISS this reporting year, demonstrating a significant increase in collaborative practice.

-

There is ongoing development of the Family Violence Practice Manual and the Helpline Standard Operating Procedures that provide guidance and direction to the Victims of Crime Helpline staff. They ensure staff understand MARAM and their responsibilities in supporting male victims of family violence. The helpline also undertook updates to the Helpline Client Relationship Management database for increased functionality to enhance triage practices currently in place to ensure L17s are prioritised, based on victim status and risk.

-

Consumer Affairs Victoria has developed a Family Violence Information Sharing Practice Toolkit, building on resources and training. The toolkit addresses gaps in practice knowledge, particularly knowing what to share, when and with whom, to support a consistent approach to information sharing for financial counsellors and Tenancy Assistance and Advocacy Program (TAAP) workers.

-

The Dispute Settlement Centre of Victoria is in the process of drafting new procedures that will assist staff with identifying clients who may be experiencing family violence.

-

Youth Justice worked collaboratively with Victoria Police and the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing towards improved, systematic information-sharing processes to inform family violence risk assessment, planning and management of young people under Youth Justice supervision. During this reporting period, Youth Justice was granted access to the L17 (police) portal to allow timely access to referral information, to inform family violence risk assessment and management.

| TAAP reflection |

|

‘Due to our external partnerships with Specialist Family Violence Services, our TAAP team regularly receives direct warm referrals. These are received directly by our TAAP workers and are always given our highest priority. Clients are contacted almost immediately upon receipt of referral. Due to our professional relationships with family violence organisations and VCAT, where there are impending VCAT hearings these matters are expedited. Often these matters entail complex family violence and assistance with removal from leases and apportionment of debts and damage caused to properties because of family violence.’ |

| Financial counsellor reflection |

|

‘A client answered ‘no’ when asked at intake if she was experiencing family violence. Going over the MARAM questions in the first appointment revealed she was fearful of her daughter when she stayed over and took drugs with her friends. Some clients do not like to open up too much during the intake, so these questions are an important opportunity to explore any concerns. She did not see herself as experiencing family violence until we went through the assessment. I was able to develop a safety plan, apply for a Flexible Support Package and negotiate debts due to the family violence. The MARAM FV Risk Assessment itself is easy to navigate and I find it flows well. It is extremely vital in not only identifying the presence of FV but also the assessment of risk and development of a safety plan.’ Mallee Family Care |

The courts

With all MCV staff trained in affected family member MARAM practice guidance and tools completed, focus has shifted to additional activities to strengthen consistent and collaborative practice. Work undertaken in 2021–22 included:

- The Pre-Court Engagement Initiative was introduced by MCV in the 2020–21 financial year to support court users through early engagement and referrals to legal and support services. The initiative has strong engagement and currently supports 7 courts. This has resulted in over 2,500 referrals to MCV’s family violence practitioners.

- Dedicated practitioners – MCV has Umalek Balit (a dedicated Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander family violence support program) and an LGBTIQA+ family violence practitioner service. Since October 2021, the Pre-Court Engagement Initiative facilitated 187 referrals to Umalek Balit practitioners and 268 referrals to LGBTIQA+ practitioners.

Victoria Police

Victoria Police has undertaken further updates to the Victoria Police Manual and Family Violence Practice Guides by way of continuous improvement in consistent and collaborative practice. The changes include:

- a new Police Manual addressing family violence involving Victoria Police employees. This covers incident response through to prosecution, application of discipline procedures, and management responsibilities for victim survivors and persons using family violence

- updated Family Violence Practice Guides, including:

- personal property conditions for Family Violence Intervention Orders that direct the return of essential property, noting exclusion conditions that enable a return to the residence to collect personal belongings in the presence of police

- taking reports of family violence by telephone, which allows prompt recording of family violence incidents where it is determined that there is no risk of harm to any party. This guide assists members to make evidence-based decisions to provide a more accurate assessment of a current family violence episode, with consideration to historical episodes

- standalone Practice Guides for priority community and diverse community responses, which are now comprehensive, standalone documents to ensure increased understanding, rather than a previous consolidated version.

[14] Recommendation 7 of the Royal Commission into family violence recommended that the Victorian Government establish a secure Central Information Point, with a summary of the information being available to RAMPS.

Information sharing

Information sharing is an indicator of consistent and collaborative practice. Where instances of information sharing are increasing, it suggests an increase in family violence being identified and practitioner confidence in the benefits of multi-agency collaboration.

As the MARAM reforms have progressed in maturity, information-sharing demand has increased considerably across the sector, when compared to the 2020–21 period. It also reflects the prescription of additional workforces in April 2021, and the impact of continued training and capability-building activities.

It should be noted that there is no legal requirement to collect FVISS and CISS data. Data that is available is from departments with the ability to collect central information. For those that do, this section outlines information-sharing demand and activity in the 2021–22 reporting period.

The courts

In 2021–22, the courts experienced significant growth in demand and received 34,326 requests for information, which is a 20 per cent increase from the previous financial year.

The Department of Families, Fairness and Housing’s Child Protection continues to be the primary source of information-sharing requests, with a total of 12,744 requests made, accounting for 37 per cent of all requests to the courts.

The number of requests received from The Orange Door network has more than doubled, with 11,938 requests received, compared to 5,475 requests in 2020–21. The Orange Door network accounted for 35 per cent of the total number of requests received by the courts.

A further 9,644 or 28 per cent of requests were received from specialist family violence service providers, including Safe Steps and other community-based organisations.

Table 2: The courts’ information-sharing activity 2021–22

| Type of activity | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Total financial year | Total since February 2018 |

| Requests | 8,007 | 7,897 | 8,575 | 9,847 | 34,326 | 91,295 |

Victoria Police

In 2021, Victoria Police introduced a new record-keeping solution for the FVISS and CISS to improve data capture, workflow processes and the output shared with other Information Sharing Entities. This is indicated in Table 3, with an increase in the number of categories now available, which has allowed for more precise data to be available for business and reporting needs.

The number of requests in this reporting period have increased significantly with 1,119 additional requests received, compared to the previous year, an increase of 20 per cent over the previous year.

Table 3: Victoria Police’s information-sharing activity 2021–22

| Type of activity | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Total financial year |

| Requests received | 1,611 | 1,533 | 1,682 | 1,794 | 6,620 |

| Shared | 1,576 | 1,508 | 1,489 | 1,688 | 6,241 |

| Not shared | 35 | 25 | 193 | 126 | 379 |

| Voluntary | 113 | 105 | 79 | 62 | 359 |

Department of Justice and Community Safety – Corrections Victoria

Corrections Victoria saw its FVISS requests double in 2021–22 compared to 2020-21. The increase is likely due to the addition of health and education services to the reforms in April 2021, and additional information requests directly to CV from The Orange Door.

To meet the increased demand, Corrections Victoria has provided additional staffing resources.