- Date:

- 16 July 2021

Introduction

The Foundation Knowledge Guide explains key elements of the MARAM Framework, as well as additional foundational knowledge to guide all professionals who will go on to use the MARAM Practice Guides.

This updated version of the Foundation Knowledge Guide (2021) includes information from both the victim survivor and perpetrator-focused practice lenses to provide a complete resource for all professionals and organisations with responsibilities under the MARAM Framework.

It includes evidence-based information about the effects and experiences of risk across a range of age groups, as well as in Aboriginal communities, diverse communities and at-risk age groups, including children, young people and older people.

2.1 A shared responsibility

It builds on the findings and recommendations of the Royal Commission, and most importantly, it provides the basis for a consistent, system-wide shared responsibility to identify, screen, assess and manage family violence across a broad range of workforces and services.

This shared responsibility stretches between individual professionals, services and whole sectors.

It gives services more options to keep victim survivors safe, and provides a stronger, more collaborative approach to holding perpetrators accountable for their actions and behaviours.

2.2 About this guide

The Foundation Knowledge Guide covers:

- a principles-based approach to practice

- the legislative authorising environment for practice under the MARAM Framework

- an overview of the service system, including entry points for service users (both victim survivors and perpetrators)

- guidance for organisational leaders, individual professionals and services to identify the responsibilities that make up their role, and how to use the victim-survivor and perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides in their work

- information about family violence — including the definition under the Act, behaviours that constitute family violence, evidence-based risk factors and presentations of risk for victim survivors caused by perpetrators’ use of violence, across age groups, and across communities

- working with child and adult victim survivors and adult perpetrators of family violence, including concepts of the predominant aggressor and misidentification

- key concepts for practice, including structured professional judgement, intersectional analysis, trauma and violence–informed practice, person or victim-centred practice, and the legislation supporting information sharing.

Overview of the MARAM Framework and resources

Family violence is an endemic issue that has terrible consequences for individuals, families and communities in Victoria.

To address this crime and improve the complex, interconnected system of services that respond to it, the Victorian Government launched Australia’s first Royal Commission into Family Violence (the Royal Commission) in February 2015. The Royal Commission delivered its report and recommendations in March 2016.

The 227 recommendations outline a vision for a Victoria that:

- is free from family violence

- keeps adults, young people and children safe

- responds to victim survivors’ wellbeing and needs

- holds perpetrators to account for their actions and behaviours.

1.1 Reforms to risk assessment and management

In particular, the Royal Commission’s recommendations focus on providing consistent, collaborative approaches to identifying, assessing and managing family violence risk.

The Royal Commission noted the strong foundations of existing practice, which was based on the Family Violence Risk Assessment and Risk Management Framework (also known as the Common Risk Assessment Framework or CRAF).

To address key gaps and issues, however, the Royal Commission recommended redeveloping the CRAF, and embedding it into the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic) (the FVPA).

1.2 The MARAM Framework

The Victorian Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM Framework) updates and replaces the CRAF.

The MARAM Framework provides a system-wide approach to risk assessment and risk management.

It aims to:

- increase the safety of people experiencing family violence

- ensure the broad range of family violence experiences and risks are represented, including for Aboriginal and diverse communities, children, young people and older people, and across identities and family and relationship types

- keep perpetrators in view of the system and hold them accountable

- align practice across the broad range of organisations that are responsible for identifying, assessing and managing family violence risk

- ensure consistent use of the framework across these organisations and between the sectors that comprise the family violence system.

To meet these aims, the MARAM Framework provides:

- 10 Framework Principles to underpin practice across the service system

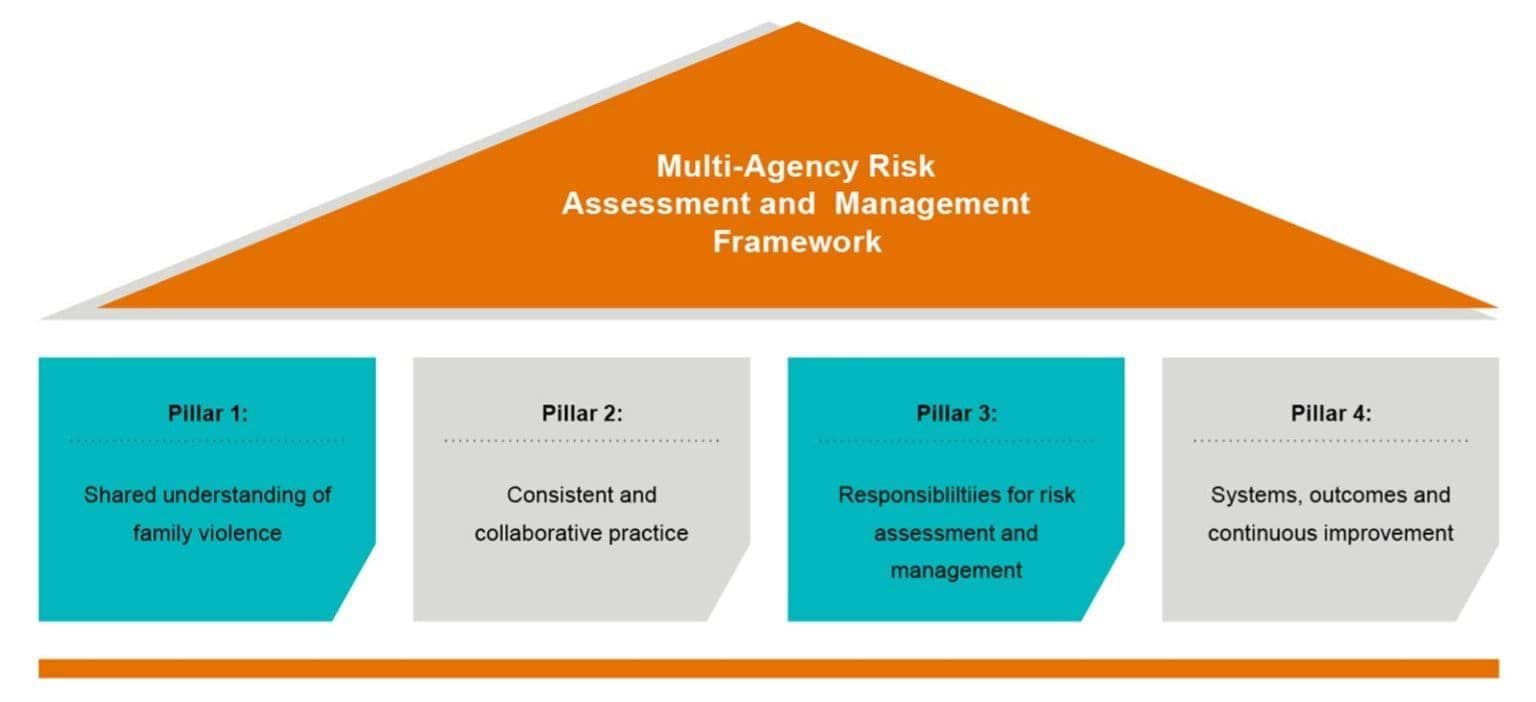

- four conceptual ‘pillars’ against which organisations will align their policies, procedures, practice guidelines and tools

- 10 Responsibilities for Practice that describe the roles and expectations of framework organisations

- information to support a shared understanding of family violence, including the experience of risk and its effect on individuals, families and communities.

In addition, the MARAM Framework provides for an expanded range of organisations and sectors that have a formal role in family violence risk assessment and risk management practice.

1.3 Prescribed organisations

Under amendments to the FVPA, organisations across the many parts of the social service system must now ensure their policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools align with the MARAM Framework.

These are known as prescribed organisations.

From April 2021, organisations and professionals covered under the reforms, include:

- 6,710 organisations and 392,000 professionals will be prescribed under MARAM

- 8,386 organisations and 408,000 professionals will be prescribed under FVISS.

Ensuring prescribed organisations align their risk assessment and management activities with the MARAM Framework means there will be a consistent response to family violence across Victoria’s service system.

1.4 Risk assessment and management responsibilities

The MARAM Framework outlines the 10 practice responsibilities that prescribed organisations must adhere to in their work with victim survivors and perpetrators of family violence:

- Responsibility 1: Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement

- Responsibility 2: Identification of family violence

- Responsibility 3: Intermediate risk assessment

- Responsibility 4: Intermediate risk management

- Responsibility 5: Seek consultation for comprehensive risk assessment, risk management and referrals

- Responsibility 6: Contribute to information sharing with other services (as authorised by legislation)

- Responsibility 7: Comprehensive assessment

- Responsibility 8: Comprehensive risk management and safety planning

- Responsibility 9: Contribute to coordinated risk management

- Responsibility 10: Collaborate for ongoing risk assessment and risk management

The MARAM Practice Guides provide practical advice for people working in prescribed organisations to embed these responsibilities in their engagement with victim survivors and perpetrators.

1.5 About this document and the MARAM Practice Guides

This document, the Foundation Knowledge Guide, is part of a suite of resources known as the MARAM Practice Guides.

These resources comprise:

- this Foundation Knowledge Guide

- MARAM Practice Guides that show you how to implement the Responsibilities in your work

- risk assessment and management tools and templates that support the MARAM Practice Guides

- the Organisation Embedding Guidance and Resources to support organisational leaders.

A MARAM Practice Guide for adolescents who use violence is currently under development.

The MARAM Framework and Practice Guides were developed through extensive consultation with experts, departmental policy and practice areas, and professionals in specialist and universal services, including those specialising in working with Aboriginal communities, diverse communities, children, young people and older people.

The MARAM Framework and Practice Guides will be evaluated and updated as the evidence base evolves.

1.5.1 Foundation Knowledge Guide

The Foundation Knowledge Guide isfor all practitioners who use the MARAM Framework.

It focuses on the legislative context, roles and interactions within the service system, risk factors, key concepts for practice, and an overview of the gendered lens and drivers of family violence and presentations of risk across different age groups and Aboriginal and diverse communities.

The Foundation Knowledge Guide is required reading for all professionals across leadership and governance, management and supervision to direct practice roles.

You should read it first before moving on to the relevant victim–survivor or perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides 1–10.

1.5.2 MARAM Practice Guides

The MARAM Practice Guides each comprise 10 chapters relating to the 10 MARAM Responsibilities. They are for professionals working with adult and child victim survivors of family violence, and adult perpetrators of family violence:

- Responsibilities for Practice Guide when working with adult and child victim survivors of family violence (2019), referred to as the victim survivor–focused MARAM Practice Guide

- Responsibilities for Practice Guide when working with adults using family violence (2021), referred to as the perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guide.

There is some overlap in content between the two sets of guides, as many of the same principles and practice concepts apply to working with both victim survivors and perpetrators.

Each guide gives you detailed advice on how to ensure your practice aligns with your organisation’s MARAM Framework responsibilities.

The guides cover applying foundation knowledge, and then build on this to provide practice guidance for:

- safe engagement

- identification of risk

- levels of risk assessment and management

- secondary consultation and referral

- information sharing

- multiagency and coordinated practice.

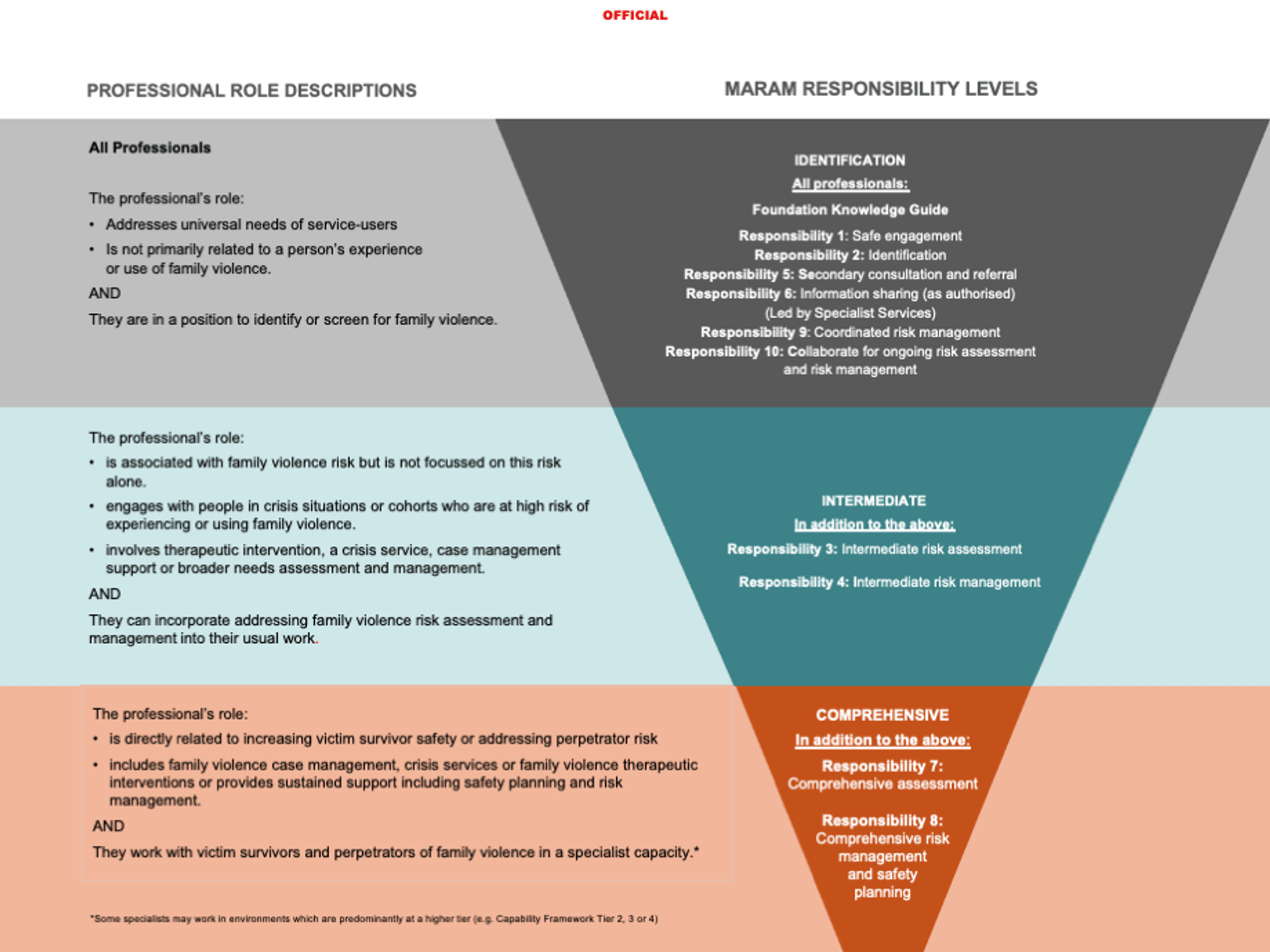

Different professionals within prescribed organisations will have different levels of responsibility, which will be informed by the contact they have with victim survivors and perpetrators.

You should work with your organisational leaders to understand your role and to identify which responsibilities to apply in practice.

You must understand how to apply each of the responsibilities that are a part of your role.

Note: Guidance on working with adolescents and young people as victim survivors is provided in the victim survivor–focused MARAM Practice Guide. Supplementary guidance for working with adolescents who use family violence will be published in 2024.

Young people aged 18 to 25 years should be considered with a developmental lens and to ensure any therapeutic needs relevant to their age and developmental stage are met. The adult perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guide has relevant information for assessing and managing risk when working with young people aged 18 to 25 years who use family violence.

Supplementary guidance for working with children and young people to directly and comprehensively assess risk and needs will be published in 2024.

1.5.3 Organisation Embedding Guidance and Resources

The Organisation Embedding Guidance and Resources are for organisational leaders. It aims to help leaders support their professionals and services in their roles and responsibilities under the MARAM Framework.

It includes specific activities organisational leaders can undertake to determine responsibilities for staff across their organisation.

Evidence-based risk factors and the MARAM risk assessment tools

There are 3 categories of risk factors under the MARAM Framework.

Comprising those that are:

- specific to an adult victim survivor’s circumstances

- caused by a perpetrator’s behaviour towards an adult or child victim survivor

- additional risk factors caused by a perpetrator’s behaviour specific to children, which recognises that children experience some unique risk factors, and that their risk must be assessed independently of adult victim survivors.

There is also a separate category reflecting children’s circumstances that may indicate (not determine in isolation) that family violence is present or escalating and should prompt assessment of children.

The risk factors reflect the current and emerging evidence base relating to family violence risk.

International evidence-based reviews[27] and consultation with academics and expert professionals have informed the development of a range of evidence-based risk factors that signal that family violence may be occurring.

This practice guidance is concerned with risk factors associated with an adult perpetrator’s family violence behaviours towards adult and child victim survivors.

Each perpetrator’s patterns of behaviour towards adult and child victim survivor(s) can be understood as coercive and controlling behaviour, or coercive control.

Perpetrators exert coercive control using a range of behaviours over time, and their effect is cumulative.

Coercive control can be exerted through any combination or pattern of the evidence-based risk factors.

It is often demonstrated through patterned behaviours of emotional, financial abuse and isolation, stalking (including monitoring of technology), controlling behaviours, to choking/strangulation, sexual and physical violence.

One occurrence of family violence behaviour can create the dynamic of ongoing coercion or control, due to the threat of possible future family violence behaviour and the resultant ongoing fear, even if ‘high-risk’ behaviours do not re-occur.

The implication for professionals working with perpetrators of family violence is that narratives and behaviours that appear innocuous may in fact be part of a pattern of behaviour making victim survivors feel unsafe and elevating their level of risk.

In addition, understanding adult and child victim survivors’ and perpetrators’ broader needs and circumstances can help you to identify, assess and manage risk according to your level of MARAM responsibility.

In Table 3, emerging evidence-informed family violence risk factors are indicated with a hash (#).

Serious risk factors — those that may indicate an increased risk of the victim being killed or almost killed — are highlighted with orange shading##.

Table 3: Evidence-based risk factors

|

Risk factors relevant to an adult victim’s circumstances |

Explanation |

|---|---|

|

Physical assault while pregnant/following new birth |

Family violence often commences or intensifies during pregnancy and is associated with increased rates of miscarriage, low birth weight, premature birth, foetal injury and foetal death. Family violence during pregnancy is regarded as a significant indicator of future harm to the woman and child victim. This factor is associated with control and escalation of violence already occurring. |

|

Self-assessed level of risk |

Victims are often good predictors of their own level of safety and risk, including as a predictor of re-assault. Professionals should be aware that some victims may communicate a feeling of safety, or minimise their level of risk, due to the perpetrator’s emotional abuse tactics creating uncertainty, denial or fear, and may still be at risk. |

|

Planning to leave or recent separation |

For victims who are experiencing family violence, the high-risk periods include when a victim starts planning to leave, immediately prior to taking action, and during the initial stages of or immediately after separation. Victims who stay with the perpetrator because they are afraid to leave often accurately anticipate that leaving would increase the risk of lethal assault. Victims (adult or child) are particularly at risk during the first two months of separation. |

|

Escalation - increase in severity and/or frequency of violence |

Violence occurring more often or becoming worse is associated with increased risk of lethal outcomes for victims. |

|

Imminence |

Certain situations can increase the risk of family violence escalating in a very short timeframe. The risk may relate to court matters, particularly family court proceedings, release from prison, relocation, or other matters outside the control of the victim which may imminently impact their level of risk. |

|

Financial abuse/difficulties |

Financial abuse (across socioeconomic groups), financial stress and gambling addiction, particularly of the perpetrator, are risk factors for family violence. Financial abuse is a relevant determinant of a victim survivor staying or leaving a relationship. |

|

Risk factors for adult or child victim survivors caused by perpetrator behaviours |

Explanation |

|

Controlling behaviours |

Use of controlling behaviours is strongly linked to homicide. Perpetrators who feel entitled to get their way, irrespective of the views and needs of, or impact on, others are more likely to use various forms of violence against their victim, including sexual violence. Perpetrators may express ownership over family members as an articulation of control. Examples of controlling behaviours include the perpetrator telling the victim how to dress, who they can socialise with, what services they can access, limiting cultural and community connection or access to culturally appropriate services, preventing work or study, controlling their access to money or other financial abuse, and determining when they can see friends and family or use the car. Perpetrators may also use third parties to monitor and control a victim or use systems and services as a form of control over a victim, such as intervention orders and family court proceedings. |

|

Access to weapons |

A weapon is defined as any tool or object used by a perpetrator to threaten or intimidate, harm or kill a victim or victims, or to destroy property. Perpetrators with access to weapons, particularly guns and knives, are much more likely to seriously injure or kill a victim or victims than perpetrators without access to weapons. |

|

Use of weapon in most recent event |

Use of a weapon indicates a high level of risk because previous behaviour is a likely predictor of future behaviour. |

|

Has ever harmed or threatened to harm victim or family members |

Psychological and emotional abuse are good predictors of continued abuse, including physical abuse. Previous physical assaults also predict future assaults. Threats by the perpetrator to hurt or cause actual harm to family members, including extended family members, in Australia or overseas, can be a way of controlling the victim through fear. |

|

Has ever tried to strangle or choke the victim |

Strangulation or choking is a common method used by perpetrators to kill victims. It is also linked to a general increased lethality risk to a current or former partner. Loss of consciousness, including from forced restriction of airflow or blood flow to the brain, is linked to increased risk of lethality (both at the time of assault and in the following period of time) and hospitalisations, and of acquired brain injury. |

|

Has ever threatened to kill victim |

Evidence shows that a perpetrator’s threat to kill a victim (adult or child) is often genuine and should be taken seriously, particularly where the perpetrator has been specific or detailed, or used other forms of violence in conjunction to the threat indicating an increased risk of carrying out the threat, such as strangulation and physical violence. This includes where there are multiple victims, such as where there has been a history of family violence between intimate partners, and threats to kill or harm another family member or child/children. |

|

Has ever harmed or threatened to harm or kill pets or other animals |

There is a correlation between cruelty to animals and family violence, including a direct link between family violence and pets being abused or killed. Abuse or threats of abuse against pets may be used by perpetrators to control family members. |

|

Has ever threatened or tried to self-harm or commit suicide |

Threats or attempts to self-harm or commit suicide are a risk factor for murder–suicide. This factor is an extreme extension of controlling behaviours. |

|

Stalking of victim |

Stalkers are more likely to be violent if they have had an intimate relationship with the victim, including during, following separation and including when the victim has commenced a new relationship. Stalking when coupled with physical assault, is strongly connected to murder or attempted murder. Stalking behaviour and obsessive thinking are highly related behaviours. Technology-facilitated abuse, including on social media, surveillance technologies and apps is a type of stalking. |

|

Sexual assault of victim |

Perpetrators who sexually assault their victim (adult or child) are also more likely to use other forms of violence against them. |

|

Previous or current breach of court orders/intervention orders |

Breaching an intervention order, or any other order with family violence protection conditions, indicates the accused is not willing to abide by the orders of a court. It also indicates a disregard for the law and authority. Such behaviour is a serious indicator of increased risk of future violence. |

|

History of family violence |

Perpetrators with a history of family violence are more likely to continue to use violence against family members and in new relationships. |

|

History of violent behaviour (not family violence) |

Perpetrators with a history of violence are more likely to use violence against family members. This can occur even if the violence has not previously been directed towards family members. The nature of the violence may include credible threats or use of weapons and attempted or actual assaults. Perpetrators who are violent men generally engage in more frequent and more severe family violence than perpetrators who do not have a violent past. A history of criminal justice system involvement (for example, amount of time and number of occasions in and out of prison) is linked with family violence risk. |

|

Obsession/jealous behaviour toward victim |

A perpetrator’s obsessive and/or excessive behaviour when experiencing jealousy is often related to controlling behaviours founded in rigid beliefs about gender roles and ownership of victims and has been linked to violent attacks. |

|

Unemployed / Disengaged from education |

A perpetrator’s unemployment is associated with an increased risk of lethal assault, and a sudden change in employment status — such as being terminated and/or retrenched — may be associated with increased risk. Disengagement from education has similar associated risks to unemployment. |

|

Drug and/or alcohol misuse/abuse |

Perpetrators with a serious problem with illicit drugs, alcohol, prescription drugs or inhalants can lead to impairment in social functioning and creates an increased risk of family violence. This includes temporary drug-induced psychosis. |

|

Mental illness / Depression |

Murder–suicide outcomes in family violence have been associated with perpetrators who have mental illness, particularly depression. Mental illness may be linked with escalation, frequency and severity of violence. |

|

Isolation |

A victim is more vulnerable if isolated from family, friends, their community (including cultural) and the wider community and other social networks. Isolation also increases the likelihood of violence and is not simply geographic. Other examples of isolation include systemic factors that limit social interaction or facilitate the perpetrator not allowing the victim to have social interaction. |

|

Physical harm |

Physical harm is an act of family violence and is an indicator of increased risk of continued or escalation in severity of violence. The severity and frequency of physical harm against the victim, and the nature of the physical harm tactics, informs an understanding of the severity of risk the victim may be facing. Physical harm resulting in head trauma is linked to increased risk of lethality and hospitalisations, and of acquired brain injury. |

|

Emotional abuse |

Perpetrators’ use of emotional abuse can have significant impacts on the victim’s physical and mental health. Emotional abuse is used as a method to control the victim and keep them from seeking assistance. |

|

Property damage |

Property damage is a method of controlling the victim, through fear and intimidation. It can also contribute to financial abuse, when property damage results in a need to finance repairs. |

|

Risk factors specific to children caused by perpetrator behaviours |

Explanation |

|

Exposure to family violence |

Children are impacted, both directly and indirectly, by family violence, including the effects of family violence on the physical environment or the control of other adult or child family members.[28] Risk of harm may be higher if the perpetrator is targeting certain children, particularly non-biological children in the family. Children’s exposure to violence may also be direct, include the perpetrator’s use of control and coercion over the child, or physical violence. The effects on children experiencing family violence include impacts on development, social and emotional wellbeing, and possible cumulative harm. |

|

Sexualised behaviours towards a child by the perpetrator |

There is a strong link between family violence and sexual abuse. Perpetrators who demonstrate sexualised behaviours towards a child are also more likely to use other forms of violence against them, such as:[29]

Child sexual abuse also includes circumstances where a child may be manipulated into believing they have brought the abuse on themselves, or that the abuse is an expression of love, through a process of grooming. |

|

Child intervention in violence |

Children are more likely to be harmed by the perpetrator if they engage in protective behaviours for other family members or become physically or verbally involved in the violence. Additionally, where children use aggressive language and behaviour, this may indicate they are being exposed to or experiencing family violence. |

|

Behaviour indicating non return of child |

Perpetrator behaviours including threatening or failing to return a child can be used to harm the child and the affected parent.[30] This risk factor includes failure to adhere to, or the undermining of, agreed childcare arrangements (or threatening to do so), threatened or actual removal of children overseas, returning children late, or not responding to contact from the affected parent when children are in the perpetrator’s care. This risk arises from or is linked to entitlement-based attitudes and a perpetrator’s sense of ownership over children. The behaviour is used as a way to control the adult victim, but also poses a serious risk to the child’s psychological, developmental and emotional wellbeing. |

|

Undermining the child–parent relationship |

Perpetrators often engage in behaviours that cause damage to the relationship between the adult victim and their child/children. These can include tactics to undermine capacity and confidence in parenting and undermining the child–parent relationship, including manipulation of the child’s perception of the adult victim. This can have long-term impacts on the psychological, developmental and emotional wellbeing of the children, and it indicates the perpetrator’s willingness to involve children in their abuse. |

|

Professional and statutory intervention |

Involvement of Child Protection, counsellors, or other professionals indicates that the violence has escalated to a level where intervention is required and indicates a serious risk to a child’s psychological, developmental and emotional wellbeing. |

|

There is evidence that the following child circumstance factors may indicate the presence or escalation of family violence risk. If any of these are present, you should undertake an assessment of risk for children. |

|

|

Risk factors specific to children’s circumstances |

Explanation |

|

History of professional involvement and/or statutory intervention |

A history of involvement of Child Protection, youth justice, mental health professionals, or other relevant professionals may indicate the presence of family violence risk, including that family violence has escalated to the level where the child requires intervention or other service support.[31] |

|

Change in behaviour not explained by other causes |

A change in the behaviour of a child that cannot be explained by other causes may indicate presence of family violence or an escalation of risk of harm from family violence for the child or other family members. Children may not always verbally communicate their concerns, but may change their behaviours to respond to and manage their own risk, which may include responses such as becoming hypervigilant, aggressive, withdrawn or overly compliant. |

|

Child is a victim of other forms of harm |

Children’s exposure to family violence may occur within an environment of polyvictimisation. Child victims of family violence are also particularly vulnerable to further harm from opportunistic perpetrators outside the family, such as harassment, grooming and physical or sexual assault. Conversely, children who have experienced these other forms of harm are more susceptible to recurrent victimisation over their lifetimes, including family violence, and are more likely to suffer significant cumulative effects. Therefore, if a child is a victim of other forms of harm, this may indicate an elevated family violence risk. |

9.1 Using assessment tools to identify and assess risk to victim survivors

The risk factors above are central to the identification, screening and assessment processes of Responsibilities 2, 3 and 7outlined in the MARAM Practice Guides.

Identification and screening with victim survivors helps you understand if risk is present, and to decide whether an immediate response is required.

Family violence risk assessment is used to understand the presentation of risk (what risk factors or ‘behaviours’ are being used by a perpetrator) and to determine level of risk. This is informed by analysing the presence and ‘seriousness’ of evidence-based risk factors and pattern of coercive control via a MARAM risk assessment tool.

The evidence-based risk factors are associated with family violence occurring and/or strongly linked to the likelihood of a perpetrator killing or seriously injuring a victim survivor.

In addition, the victim survivor–focused MARAM Practice Guides describe how risk factors might be experienced in Aboriginal communities, diverse communities and for older people, children and young people. The victim survivor–focused risk assessment tools provide specific questions tailored to these communities to help determine if risk factors are present.

For example, for people with disabilities, the comprehensive assessment tool asks whether anyone in the person’s family has used their disability against them (a manifestation of the ‘controlling behaviours’ risk factor for people with disabilities).

New evidence will emerge as professionals use the MARAM assessment tools and Practice Guides, which account for a broad range of experiences across the spectrum of seriousness and presentations of risk.

This will inform continuous improvement and practice change through future updates to the MARAM Framework and Practice Guides.

9.2 Using assessment tools to identify and assess risk by perpetrators

Victim survivor safety is the primary consideration when working with perpetrators.

When identifying and assessing the risk presented by perpetrators, professionals use their understanding of how family violence risk factors and patterns of family violence behaviours are targeted towards, and experienced by, adult and child victim survivors.

The MARAM risk factors also underpin the design of the perpetrator-focused identification and assessment tools under Responsibilities 2, 3 and 7 of the perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides.

A person’s narratives, behaviours, presenting needs and circumstances can support identification of indicators or risk factors demonstrating their use of family violence behaviours.

The perpetrator-focused risk identification and assessment tools support observation, information gathering, contextualisation of presenting needs and circumstances and processes for direct assessment of the perpetrator, without colluding with or minimising or justifying their use of violence. The assessment tools also enable identification of patterns of coercive and controlling behaviours, points of escalation and opportunities for intervention.

In addition, these tools support information sharing to ensure the experience of the victim survivor is central to assessing the level of risk and developing risk management interventions.

You should determine victim survivors’ identity, circumstances, impacts of disadvantage or lived experience in order to understand how perpetrators may target these as part of their pattern of coercive controlling behaviour.

You should also be aware that perpetrators’ own lives are complex, and they may have had experiences of family violence (for example, when they were children) and other forms of discrimination and oppression.

Understanding perpetrators in their context is important to support more accurate identification, risk assessment and tailored risk management plans.

A principles-based approach to practice

The MARAM Framework, Foundation Knowledge Guide and victim-survivor and perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides are guided by 10 MARAM Principles.

These principles provide professionals and services with a shared understanding of family violence. They will ensure consistent, effective and safe family violence responses for adult and child victim survivors as well as adult perpetrators, while centralising perpetrator accountability.

The principles are underpinned by the right of all people to live free from family violence. They inform the ethical engagement of professionals and services working with all service users, both victim survivors and perpetrators.

The 10 principles are:

- Family violence involves a spectrum of seriousness of risk and presentations, and is unacceptable in any form, across any community or culture.

- Professionals should work collaboratively to provide coordinated and effective risk assessment and management responses, including early intervention when family violence first occurs to avoid escalation into crisis and additional harm.

- Professionals should be aware, in their risk assessment and management practice, of the drivers of family violence, predominantly gender inequality, which also intersect with other forms of structural inequality and discrimination.

- The agency, dignity and intrinsic empowerment of victim survivors must be respected by partnering with them as active decision-making participants in risk assessment and management, including being supported to access and participate in justice processes that enable fair and just outcomes.

- Family violence may have serious impacts on the current and future physical, spiritual, psychological, developmental and emotional safety and wellbeing of children, who are directly or indirectly exposed to its effects, and should be recognised as victim survivors in their own right.

- Services provided to child victim survivors should acknowledge their unique experiences, vulnerabilities and needs, including the effects of trauma and cumulative harm arising from family violence.

- Services and responses provided to people from Aboriginal communities should be culturally responsive and safe, recognising Aboriginal understanding of family violence and rights to self-determination and self-management, and take account of their experiences of colonisation, systemic violence and discrimination and recognise the ongoing and present day impacts of historical events, policies and practices.

- Services and responses provided to diverse communities and older people should be accessible, culturally responsive and safe, service-user centred, inclusive and non-discriminatory.

- Perpetrators should be encouraged to acknowledge and take responsibility to end their violent, controlling and coercive behaviour, and service responses to perpetrators should be collaborative and coordinated through a system-wide approach that collectively and systematically creates opportunities for perpetrator accountability.

- Family violence used by adolescents is a distinct form of family violence and requires a different response to family violence used by adults, because of their age and the possibility that they are also victim survivors of family violence.

3.1 Principles for working with perpetrators

As a result of recommendations from the Royal Commission, the Victorian Government formed the Expert Advisory Committee on Perpetrator Interventions (EACPI) to provide advice on how to increase accountability of family violence perpetrators.

In its final report, the EACPI outlines eight principles for perpetrator interventions.

These are consistent with and supplement the MARAM Principles. They provide for a strong victim-focused lens and support perpetrator accountability at the individual, service and systems level.

The EACPI principles also inform ethical practice of professionals in their engagement with all service users.

They ensure that victim survivor safety is the key consideration when working directly with perpetrators to address their risk and needs.

Legislative, policy and practice environments

The MARAM Framework is embedded in Victorian law and policy.

It establishes the architecture and accountability mechanisms of a system-wide approach to, and shared responsibility for, responding to the family violence risk that perpetrators cause.

These elements are set at the organisational level.

They provide the authorising environment, and enablers of practice, for individual professionals and services within organisations in their work with adult and child victim survivors and adult perpetrators.

4.1 Key aspects of the MARAM Framework

- Part 11 of the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (FVPA) establishes the authorising environment for the MARAM Framework by creating a legislative instrument and enabling prescription of organisations through regulation.

- The Framework’s legislative instrument describes the four pillars, the requirements for alignment, the guiding principles, the 10 Responsibilities for practice, and the evidence-based risk factors.

- ‘Framework organisations’ and ‘section 191 agencies’ are prescribed under the Family Violence Protection (Information Sharing and Risk Management) Regulations 2018. Prescribed organisations are required to progressively align their policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools with the Framework legislative instrument.

- The MARAM Framework complements and provides further information about the legislative instrument.

4.2 Information Sharing Schemes

The Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme is a key enabler of the MARAM Framework and associated Practice Guides.

- Part 5A of the FVPA establishes the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme, which allows prescribed organisations to share information relevant to family violence risk assessment and management practice, in relation to victim survivor and perpetrator-focused Responsibilities 5 and 6.

- The Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme Guidelines outline how information is to be shared in practice.

The Child Information Sharing Scheme further assists in responding to safety and wellbeing for children.

- Part 6A of the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005 (Vic.) establishes the Child Information Sharing Scheme, which allows the sharing of information for the purpose of promoting a child’s wellbeing or safety, including but not limited to the context of family violence. This may include information relating to a child’s stabilisation and recovery from family violence, reflected in the protective factors outlined in victim survivor–focused Responsibility 3.

Other complementary information sharing and reporting obligations continue to apply.

- The Information Sharing Schemes do not affect the reporting obligations created under other legislation, such as mandatory reporting under the Children, Youth and Families Act 2005 (Vic.).

- The Information Sharing Schemes complement and build on existing permissions held by organisations and services to share information under other laws, such as the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 (Vic.), the Health Records Act 2001 (Vic.), and the Children Youth and Families Act 2005 (Vic.).

4.3 Policy and practice direction

The MARAM Framework and Practice Guides, including this Foundation Knowledge Guide, provide policy and practice direction.

They are for professionals and leaders working within prescribed organisations and services that undertake family violence risk assessment and risk management practice in Victoria.

Leaders of prescribed organisations make decisions at the organisational level to identify the practice responsibilities for their professionals and services and ensure they are applied in practice.

Professionals need to have a clear understanding of their own role in relation to responding to family violence within the broader service system.

This will help to determine which level of risk identification, assessment and management applies to your role and which MARAM Responsibilities and Practice Guides are relevant to your work.

More detail on the legislative, policy and practice environment is described in ‘Part B: System architecture and accountability’ of the MARAM Framework.

4.4 The MARAM Framework Pillars

The MARAM Framework is structured around four conceptual pillars. Organisations will align their risk assessment and management policies, procedures, practice guidelines and tools with these pillars.

Each pillar has its own objective and requirement for alignment. The objectives of the pillars are outlined below.

4.4.1 Pillar 1: Shared understanding of family violence

Everyone working in the service system, regardless of their role, needs to have a shared understanding of family violence and perpetrator behaviour, including its drivers, presentation, prevalence and impacts.

This enables a consistent approach to risk assessment and management across the service system and helps keep perpetrators in view and accountable and victim survivors safe.

Pillar 1 creates a shared understanding of:

- what constitutes family violence, including common perpetrator actions, behaviours and patterns of coercion and control

- the causes of family violence, particularly community attitudes about gender, and other forms of inequality and discrimination

- established evidence-based risk factors, particularly those that relate to increased likelihood and severity of family violence.

4.4.2 Pillar 2: Consistent and collaborative practice

Pillar 2 builds on the shared understanding of family violence created in Pillar 1 by developing consistent and collaborative practice for family violence risk assessment and management across different professional roles and sectors.

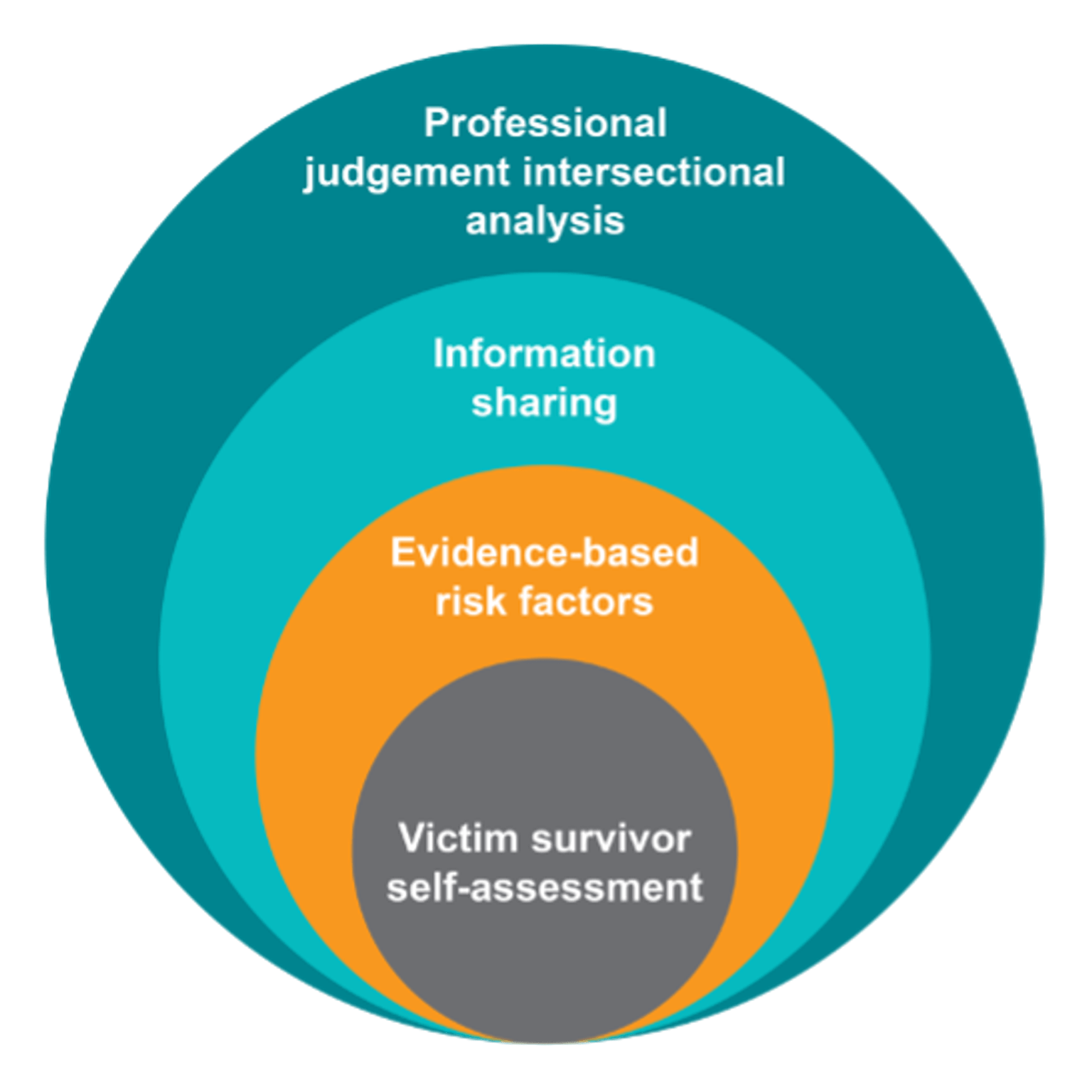

You should use Structured Professional Judgement in your role to assess the level or ‘seriousness’ of risk, informed by:

- the victim survivor’s self-assessed level of risk

- evidence-based risk factors (using the relevant assessment tool)

- sharing information with other professionals as appropriate to help inform professional judgement and decision-making

- using an intersectional analysis when applying professional judgement to determine the level of risk.

4.4.3 Pillar 3: Responsibilities for risk assessment and management

Pillar 3 builds on Pillars 1 and 2. It describes responsibilities for facilitating family violence risk assessment and management.

It provides advice on how professionals and organisations define their responsibilities to support consistency of practice across the service system, and to clarify the expectations of different organisations, professionals and service users.

4.4.4 Pillar 4: Systems, outcomes and continuous improvement

Pillar 4 outlines how organisational leaders and governance bodies contribute to, and engage with, system-wide data collection, monitoring and evaluation of tools, processes and implementation of the Framework.

This pillar describes how aggregated data will support better understanding of service user outcomes and systemic practice issues, and it will assist in continuous practice improvement.

This information will also feed into the legislated five-yearly reviews of the Framework to ensure it continues to reflect evidence-based best practice.

Terminology and definitions

Language relating to family violence and individual identities is always evolving and can vary for individuals and communities.

Language relating to family violence and individual identities is always evolving and can vary for individuals and communities.

As practitioners, it is important to use language that service users are comfortable with. This helps build trust and keep the person engaged.

This section provides guidance about some commonly used terminology. The MARAM Practice Guides also contain information on identity that will help you talk to service users.

Throughout this guide, the term Aboriginal people is used to refer to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The terms diverse communities and at-risk age groups are used broadly, and include:

- diverse cultural, linguistic and faith communities

- people with disability

- people experiencing mental health issues

- LGBTIQ people

- women in or exiting prison or forensic institutions

- people who work in the sex industry

- people living in regional, remote and rural communities

- male victim survivors

- older people (aged 65 years and older, or 45 years and older for Aboriginal people)

- children (0 to 4 years of age are most at risk) and young people (12 to 25 years of age).

A full list of definitions is provided at the end of this document in Section 14, ‘Definitions’.

5.1 Language around gender

The MARAM Practice Guides use an intersectional analysis and feminist lens, which strongly acknowledge that family violence is gendered.

However, gendered language is not used to describe every form of family violence. This is to ensure we encompass the full range of victim survivors who may experience family violence, including those who may have historically had difficulty being recognised.

In line with the Royal Commission and the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme Guidelines, this document and the MARAM Practice Guides refer to victim survivors and perpetrators (or person using violence),recognising that these are the most widely used terms in the community.

The term victim survivor refers to adults, children and young people who experience family violence.

Under the FVPA, children are considered victim survivors if they experience family violence directed at them, or they are exposed directly to family violence and/or its effects.

Women who use force describes victim survivors who, in their intimate partner relationships, have used force in response to violence where there is a pattern and history of ongoing perpetration of violence against them.[1] This may sometimes be referred to as ‘violent resistance’ or ‘resistive violence’. Section 12.1.13 on ‘Women who use force in heterosexual intimate partner relationships’ provides further guidance.

Some women who use force who are victim survivors do not identify as victims, because this does not match with their experience as ‘strong’ or ‘weak’, and their use of force may be in response to pushing back against a ‘weaker’ identity of victim survivor.[2]

Women who use force in response to a pattern of family violence and coercive control from a perpetrator/predominant aggressor are not themselves perpetrators. However, if you are uncertain about the identity of a victim survivor or predominant aggressor/perpetrator, refer to Section 12.2.1, ‘Perpetrator/predominant aggressor and misidentification’.

5.2 Variations of language

Recognised variations of language include the following:

- Aboriginal people and communities may prefer to use the term people who use violence rather than perpetrator.

- Aboriginal people and communities may prefer to use the term people who experience violence rather than victim survivor.

- Parts of the service system use the term men who use violence rather than perpetrator, particularly in client/service user–facing practice settings that work exclusively with men.

- For adolescents and young people, the term adolescent or young person who uses family violence is used, rather than perpetrator. This form of family violence requires a distinct response, given the age and developmental stage of the young person and their concurrent safety and developmental needs and circumstances. In addition, it is common for the adolescent or young person to have experiences of past or current family violence perpetrated by other family members. The term is applied across a broad age range from 10 to 18 years.

- Family violence towards an older person is often described as elder abuse. In this document, elder abuse refers to family violence experienced by older people within the family or family-like contexts, including co-resident violence in residential care services and supported residential settings, as it is defined in the FVPA. It does not extend to elder abuse from professional carers occurring outside the family context, such as in institutional or community settings.

- Family violence towards or between persons with a disability or a young person within the family or family-like relationships, such as residential care facilities, is included as it is defined in the FVPA. It does not extend to professional carer relationships outside of the family context, such as in institutional settings.

5.3 Language used in the justice system

Other terms may be used for different functions or points in time within the service system.

These include terms used in the justice system:

- Police-made applications for family violence intervention orders use the term affected family member to describe the person who is to be protected by the order, and the term respondent or other party to describe the person against whom the order is sought.

- In applications for intervention orders that are not made by police, the term applicant is used to describe the person seeking the order who may be an affected family member or another person making the application on their behalf, and respondent is used to describe the person against whom an order is sought.

- The term accused is used to describe a person being prosecuted for a family violence offence, and offender describes a person who has been found guilty of an offence.

5.4 Language relating to perpetrators

The term person using family violence is used through this guide and the MARAM Practice Guides to refer to the person causing family violence harm.

The term perpetrator is used at a legal and policy level in Victoria. The term is used in this guide in relation to policy statements.

When discussing violence across a range of identities and communities, the terms men who use family violence and/or person using family violence can be used, as applicable.

In direct practice with a person using violence, you should not use the term perpetrator. It is a label that de-emphasises the person’s agency for change, and in practice it may make them feel judged and more hostile or resistant to engaging with you.

If you are working with adult and child victim survivors, they may not feel comfortable with the use of the word perpetrator when they are seeking support. Understanding and mirroring the words a victim survivor uses to describe their parent, partner, ex-partner, or family member is also an important part of the engagement process in direct practice.

In addition, the use of the term perpetrator can limit your own capacity to understand or consider the person in their context, that is their presenting needs, history and experiences, risks, strengths and environmental contexts or circumstances that contribute to their use of violence. This label may also impact professionals’ capacity to apply an intersectional lens and adopt trauma and violence–informed approaches (where appropriate).

The term perpetrator accountability[3] refers to systemic legislative and policy responses that keep perpetrators in view of the service system and held to account for their behaviour. It also refers to how an individual can take personal accountability for safety and change.

This term encompasses a range of actions and approaches that occur at the:

- the individual level (by and with the person using violence) it means that perpetrators are encouraged to take responsibility for their use of violence and its impacts and to change their behaviour to stop using violence.

- the service level (by professionals in applying accountability in practice through risk assessment and management of the person using violence) it means that wherever perpetrators interact with the service system, the primary consideration is to support the safety, wellbeing and needs of victim survivors, and to avoid collusion while providing support for perpetrators to gain awareness, take responsibility and engage in positive behaviour change.

- system level (system-wide policy or direct interventions or other accountability measures) it means there is a collective responsibility to keep perpetrators ‘in view’. This ensures that perpetrators’ use of violence and control is seen as unacceptable at a community level, and there are clear consequences for family violence, underpinned by legislation and compliance measures.

Perpetrator accountability includes:

- understanding and responding to the needs of victim survivors, their experiences of perpetrators’ use of violence, and their views about the outcomes they are seeking to achieve

- prioritising women and children’s safety through effective, coordinated and ongoing risk assessment and management[4]

- encouraging perpetrators to take responsibility for their actions, including the impact of their actions on family members such as intimate partners and their children

- providing options to assist perpetrators to gain insight into and awareness of their actions and change their behaviour, tailored to their risk profile

- a strong set of laws and legal processes that impose clear consequences and sanctions for perpetrators' violent and abusive behaviour and failure to comply with police interventions and court orders

- fostering collective responsibility among government and non-government agencies, the community and individuals for denouncing perpetrators’ use of violence.

Who has a role in the service system?

Family violence risk assessment and management is a shared responsibility across Victoria’s service system.

As the final report of the Royal Commission states:

Broadening responsibility for addressing family violence will require each sector or component part of the system to reinforce the work of others, collaborate with and trust others, to understand the experience of family violence in all its forms.[5]

Professionals from a broad range of services, organisations, professions and sectors have a shared responsibility for identifying, assessing and managing family violence risk, even where it may not be core business.

Together, they form the family violence service system, and are formally recognised and prescribed by regulation as ‘framework organisations’. The full list of framework organisations is available online.

Many professionals who have not traditionally had a role in assessing and managing family violence risk with victim survivors or perpetrators will now need to be familiar with these processes.

You are not expected to become a family violence expert – but everyone has a role.

This will vary based on the nature of your organisation and the type of contact you have with people experiencing and using family violence.

The MARAM Framework and Practice Guides are designed to help professionals in the service system, spanning specialist family violence services, community services, health, justice and education, to work together in responding to family violence, supporting victim survivors to be safe and recover from violence, and keeping perpetrators in view and held to account.

Given the prevalence of family violence, it is likely that most professionals and services across the community will come into contact with people experiencing and using family violence.

Any organisations not prescribed as ‘framework organisations’ can be guided by the MARAM Framework to identify how adult and child victim survivors can be better supported to disclose, be safe and recover from family violence, and to engage with perpetrators to invite personal accountability for their use of violence and motivate them to change.

While non-prescribed organisations and professionals are not required under the FVPA to align their policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools with the MARAM Framework, they are encouraged to do so.

This includes understanding the MARAM Framework and its application to their service users and incorporating relevant guidance on foundation knowledge and responsibilities into their work.

You may find the MARAM Framework and the Practice Guides can improve your response to family violence and assist with intervening earlier and connecting service users to the family violence service system.

6.1 Working with perpetrators

Professionals across the service system have a role in keeping perpetrators engaged and in view of services, contributing to accountability for their use of family violence and supporting them to change their behaviour – whether directly or indirectly.

The Royal Commission identified opportunities for a broader range of professionals and sectors to play a role in the integrated family violence system and support identification, risk assessment and management of people who use violence.[6] Working with people using violence can support professionals and the service system to keep victim survivors safe from violence. Identifying, assessing and managing family violence risk are crucial elements of a broad robust approach to perpetrator accountability.

Your professional and sector role will determine your level of responsibility in relation to perpetrators, and guidance and tools are provided in the perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guide.

6.1.1 Increased risk arising from perpetrator interventions

Interventions with perpetrators may increase risk to adult and child victim survivors.

They may also increase a perpetrator’s risk to themselves (from suicide or self-harm) or to professionals/community (such as threats to harm). Call Triple Zero (000) in an emergency or if there is imminent risk.

You should understand the potential for certain interventions to adversely affect people using violence from Aboriginal communities based on their connection, or lack of connection, to community and culture.

Seek secondary consultation with specialist Aboriginal community organisations to inform your understanding of interventions and their possible unintended effects.

Refer to your service’s policies and procedures for working with service users both within agency environments and when conducting home visits or outreach activities.

If you have a role in also working with a victim survivor, consider if it is safe, appropriate and reasonable to contact them and share information about increased risk, or another service working with a victim survivor to respond to increased risk.

Plan your approach to assessment to support safe engagement.

You should also engage in reflective practice and supervision to explore both perceived and real risks to your own safety, including any fears you have of directly working with perpetrators.

In planning with your supervisor, determine required supports, ways to manage risks to yourself and the service user, and alternative arrangements, if appropriate, to support the engagement and monitoring of the person using violence.

Secondary consultation with specialists may support your safe engagement.

Share information with other engaged services to ensure support is provided for the victim survivor as needed, due to increased risk that may arise from some perpetrator interventions if not actively managed.

The Organisation Embedding Guidance and Resources contains more information on worker safety.

MARAM practice responsibilities for professionals

Pillar 3 of the MARAM Framework outlines 10 Responsibilities of practice for professionals working in organisations and sectors across the family violence service system.

Organisational leaders will support professionals and services to identify which victim-survivor and perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides are relevant for their role and functions.

The Practice Guides have been developed for working directly with service users (victim survivors and/or perpetrators).

Responsibilities 1, 2, 5, 6, 9 and 10 as outlined below apply to all relevant professionals and services within prescribed organisations.

Some professionals also have a role in risk assessment and management at either the intermediate (Responsibilities 3 and 4) or comprehensive (Responsibilities 7 and 8) levels.

All organisational leaders in prescribed framework organisations are required to understand the roles and responsibilities of professionals and services within their organisation.

Identifying and mapping these roles within and across the organisation will support shared understanding of roles and responsibilities.

This will help professionals and services to work together to identify, assess and manage family violence risk through information sharing, secondary consultation and referral.

Remember

Professionals across a range of services and sectors have a role in working with victim survivors and/or perpetrators of family violence. The MARAM Practice Guides reflect what a professional should know to work with adult and child victim survivors, and adult perpetrators.

Table 1: Description of each practice responsibilities[7]

|

Risk assessment and management responsibilities |

Expectations of framework organisations and section 191 agencies |

|

Responsibility 1: Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement |

Ensure staff understand the nature and dynamics of family violence, facilitate an appropriate, accessible, culturally responsive environment for safe disclosure of information by victim survivor service users, and to respond to disclosures sensitively. Ensure staff recognise that any engagement of service users who may be a perpetrator must occur safely and not collude or respond to coercive behaviours. |

|

Responsibility 2: Identification of family violence |

Ensure staff use information gained through engagement with service users and other providers (and in some cases, through use of screening tools to aid identification/or routine screening of all service users) to identify indicators of family violence risk and potentially affected family members. Ensure staff recognise that any engagement with a service user who may be a perpetrator must also be culturally responsive and respond to coercive behaviours in a safe, non-collusive way. |

|

Responsibility 3: Intermediate risk assessment |

Ensure staff can competently and confidently conduct intermediate risk assessment of adult and child victim survivors using Structured Professional Judgement and appropriate tools, including the Brief and Intermediate Assessment tools. Where appropriate to the role and mandate of the organisation or service, and when safe to do so, ensure staff can competently and confidently contribute to risk assessment through engagement with a perpetrator, including using Structured Professional Judgement and the Intermediate Assessment, and contribute to keeping them in view and accountable for their actions and behaviours. |

|

Responsibility 4: Intermediate risk management |

Ensure staff actively address immediate risk and safety concerns relating to adult and child victim survivors, and undertake intermediate risk management, including safety planning. Those working directly with perpetrators attempt intermediate risk management when safe to do so, including safety planning. |

|

Responsibility 5: |

Ensure staff seek internal supervision and further consult with family violence specialists to collaborate on risk assessment and risk management for adult and child victim survivors and perpetrators, and make active referrals for comprehensive specialist responses, if appropriate. |

|

Responsibility 6: Contribute to information sharing with other services (as authorised by legislation) |

Ensure staff proactively share information relevant to the assessment and management of family violence risk and respond to requests to share information from other information sharing entities under the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme, privacy law or other legislative authorisation. |

|

Responsibility 7: Comprehensive assessment |

Ensure staff in specialist family violence positions are trained to undertake Comprehensive assessment of risks, needs and protective factors for adult and children victim survivors. Ensure staff who specialise in working with perpetrators are trained and equipped to undertake Comprehensive risk and needs assessment to determine seriousness of risk of the perpetrator, tailored intervention and support options, and contribute to keeping them in view and accountable for their actions and behaviours. |

|

Responsibility 8: Comprehensive risk management and safety planning |

Ensure staff in specialist family violence positions are trained to undertake comprehensive risk management through development, monitoring and actioning of safety plans (including ongoing risk assessment), in partnership with the adult or child victim survivor and support agencies. Ensure staff who specialise in working with perpetrators are trained to undertake comprehensive risk management through development, monitoring and actioning of risk management plans (including information sharing); monitoring across the service system (including justice systems); and actions to hold perpetrators accountable for their actions. This can be through formal and informal system accountability mechanisms that support perpetrators’ personal accountability, to accept responsibility for their actions, and work at the behaviour change process. |

|

Responsibility 9: Contribute to coordinated risk management |

Ensure staff contribute to coordinated risk management, as part of integrated, multidisciplinary and multiagency approaches, including information sharing, referrals, action planning, coordination of responses and collaborative action acquittal. |

|

Responsibility 10: Collaborate for ongoing risk assessment and risk management |

Ensure staff are equipped to play an ongoing role in collaboratively monitoring, assessing and managing risk over time to identify changes in assessed level of risk and ensure risk management and safety plans are responsive to changed circumstances, including escalation. Ensure safety plans are enacted. |

The Organisation Embedding Guidance and Resources and the Responding to family violence capability framework provides information for organisational leaders on how to support their staff to identify the 10 Responsibilities that apply to their roles and services.

The relevant knowledge and skill indicators have been considered in the development of these MARAM Practice Guides for the MARAM Framework.

The MARAM Framework and Practice Guides should be interpreted to complement and build on existing practice frameworks, that will also continue to apply.

A high-level description of the MARAM Responsibilities and role descriptions are in Figure 2.

7.1 How victim survivors or perpetrators access the service system

Victim survivors and perpetrators of family violence can access or interact with the family violence service system in a number of ways including:

Table 2: Entry points and services

|

Entry points |

Description of service types |

|

Specialist family violence and sexual assault services |

Specialist family violence services[8] such as crisis refuge services and services that specialise in working with Aboriginal communities, diverse communities and older people experiencing family violence or using family violence Multi-Disciplinary Centres and sexual assault support services |

|

The Orange Door |

Specialist family violence services for adult and child victim survivors, child and family services, adult perpetrator services |

|

Victim Support Agency |

Specialist family violence responses for adult male victims |

|

Prescribed justice and statutory bodies |

Police, courts, tribunals and correctional services, services for victims of crime, Child Protection and legal services[9] |

|

Prescribed universal services |

Education, social/public housing services, health services, maternal and child health services, state funded aged care services, mental health services, drug and alcohol services, disability services, financial counselling and community-based child and family services |

|

Targeted community services |

Services (in addition to community-specific specialist family violence services, above) with an expert knowledge of a particular diverse community and the responses required to address the unique needs and barriers faced by this group. Targeted services may also include community-specific services, such as ethno-specific, LGBTIQ and disability services that focus on primary prevention or early intervention. |

Having multiple entry points to the family violence service system means people can access the services they need and also be connected to appropriate support in relation to their experience or use of family violence.

A broad range of sectors and organisations serve as entry points for victim survivors and perpetrators[10] through risk identification, assessment and risk management, as appropriate to their role and the responsibilities embedded within their internal policy arrangements.

These sectors and organisations must also work with other services (such as specialist family violence services) to support coordinated and collaborative responses to family violence risk, such as sharing information to support risk assessment and management through secondary consultation.

About family violence

Family violence is behaviour that controls or dominates a family member and causes them to fear for their own or another person’s safety or wellbeing.

Family violence is behaviour that controls or dominates a family member and causes them to fear for their own or another person’s safety or wellbeing.

It includes exposing a child to these behaviours, as well as their effects and impacts. Family violence presents across a spectrum of risk, ranging from subtle exploitation of power imbalances, through to escalating patterns of abuse over time.

As described throughout this Foundation Knowledge Guide, family violence is deeply gendered. While people of all genders can be perpetrators or victim survivors of family violence, overwhelmingly, perpetrators are men, who largely perpetrate violence against women (who are their current or former partner) and children.

However, family violence can occur in a range of ways across different relationship types and communities, including but not limited to the following:

- children and young people as victim survivors in their own right who have unique experiences, vulnerabilities and needs

- older peoples’ experiences of family violence, often described as elder abuse, from intimate partners, adult children or carers, or extended family members

- varying experiences of family violence for people from Aboriginal communities may occur in intimate relationships, other family relationships, from people outside of the Aboriginal community who are in intimate relationships with Aboriginal people, and violence in extended families, kinship networks and community violence, or lateral violence, within the Aboriginal community (often between Aboriginal families).It extends to one-on-one fighting, abuse of Aboriginal community workers, as well as self-harm, injury and suicide[11]

- experiences of family violence for people from diverse communities, including in intimate relationships, extended family networks community violence and violence from a family of origin.

The FVPA provides a broad definition of family violence and ‘family’ or ‘family-like’ relationships, as outlined below. Family violence takes a variety of forms and occurs in a range of relationships, including and outside of intimate, domestic partners. The Preamble to the FVPA also notes a range of features of family violence and its significant effects on individuals, communities and families.

8.1 How the Act defines family violence

The FVPA defines family violence as behaviour by a person towards a family member or person that is:

- physically or sexually abusive

- emotionally or psychologically abusive

- economically abusive

- threatening

- coercive

- in any other way controls or dominates the family member and causes that family member to feel fear for the safety or wellbeing of that family member or another person.

It also includes behaviour by a person that causes a child to hear or witness, or otherwise be exposed to the effects of behaviour referred to in these ways.

Examples of family violence that are referred to in the Act (s. 5(2)) include:

- assaulting or causing personal injury to a family member, or threatening to do so

- sexually assaulting a family member or engaging in another form of sexually coercive behaviour, or threatening to engage in such behaviour

- intentionally damaging a family member’s property, or threatening to do so

- unlawfully depriving a family member of their liberty or threatening to do so

- causing or threatening to cause the death of, or injury to, an animal, whether or not the animal belongs to the family member to whom the behaviour is directed, so as to control, dominate or coerce the family member.

Coercive control

Coercive control is recognised within the FVPA, where family violence is framed as ‘patterns of abuse over a period of time’, inclusive of behaviours that coerce, control and dominate family members.[12] Coercive control is central to the definition of family violence within Victoria and understanding of risk identification and assessment.

Coercive control is not a standalone form of family violence. The term reflects the pattern and underlying feature or dynamic created by a perpetrator’s tactics and use of family violence and its felt impact or outcome on victim survivors.[13] As a tactic, coercive control can include any combination of family violence behaviours (risk factors) used by a perpetrator to create a pattern or ‘system of behaviours’ intended to harm, punish, frighten, dominate, isolate, degrade, monitor or stalk,[14] regulate and subordinate the victim survivor.

Coercive controlling behaviours may or may not include physical or sexual assault or threats to kill the adult or child victim survivor. However, the use or threat of these behaviours, even once, can create significant, ongoing threat of reoccurrence, creating and reinforcing an environment of coercive control.

The power and control dynamics underpinning family violence can have significant cumulative psychological, spiritual and cultural, physical and financial impacts on victim survivors. This can undermine a victim’s autonomy, capacity for resistance and sense of identity and self-worth.[15] A victim survivor can feel trapped within their experience of coercive control, where their options for accessing safety and support are removed, restricted or regulated.

High levels of coercive control are an indicator for increased likelihood of adult or child victim survivor/s being killed or seriously injured.[16]

Recognising patterns of behaviour that underpin coercive control can enable broader recognition of family violence outside of overt or discrete ‘incidents’ of physical and sexual violence.