- Date:

- 27 Feb 2020

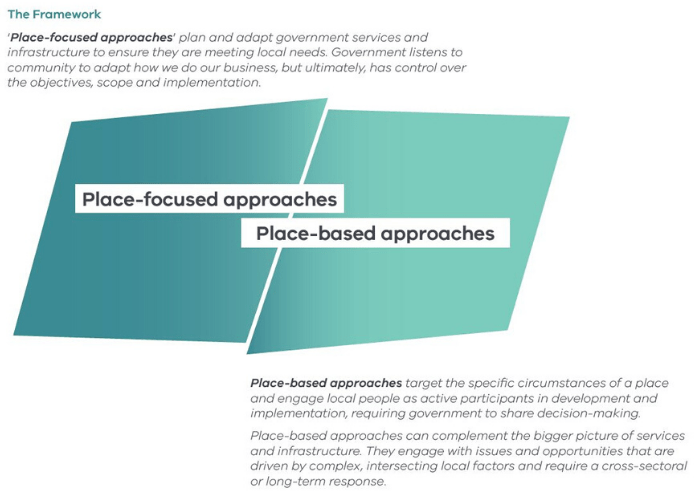

To continually improve how we work in place, we need to have a clear and shared understanding and way of talking about it. The Victorian Government’s Framework for Place-Based Approaches describes a way of thinking about place that will better enable Victorian Public Service employees to effectively communicate across government.

The framework clarifies the difference between approaches that invite local communities to inform or contribute to government decision-making (place-focused) and those where we hand over control or are an equal partner in decision-making with communities (place-based).

Place-focused approaches

- Plan and adapt government services and infrastructure to ensure they are meeting local needs.

- Government listens to community to adapt how we do our business, but ultimately, has control over the objectives, scope and implementation.

Place-based approaches

- Can complement the bigger picture of services and infrastructure. They engage with issues and opportunities that are driven by complex, intersecting local factors and require a cross-sectoral or long-term response.

- Place-based approaches target the specific circumstances of a place and engage local people as active participants in development and implementation, requiring government to share decision-making.

Executive summary

This section provides an executive summary of the Framework for place-based approaches.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Aboriginal people as the First Peoples and Traditional Owners and custodians of the land and water on which we all rely. We acknowledge that Aboriginal communities are steeped in traditions and customs, and we respect this. We acknowledge the continuing leadership role of the Aboriginal community in striving to redress inequality and disadvantage and the catastrophic and enduring effects of colonisation.

This framework is the start of a conversation about how we can resource, learn from and support place-based initiatives more consistently across government.

To tackle the broad opportunities and challenges facing us - urbanisation, inequality, intergenerational disadvantage, demographic shifts, environmental change - we need to see them from a local perspective and work with local people and communities.

Working with communities is a key capability for government

With higher expectations of government, the community’s trust in government institutions to meet their needs is declining. Interventions planned, funded and coordinated centrally by government are not enough to deal with the complex challenges that some Victorians face. In this context, ‘place’ can provide a

valuable focus point for government. It can help to:

- support civic engagement by enabling communities to apply local skills and strengths, and have a sense of ownership over decisions that are made

- think holistically and systematically by helping to understand how systems impact on people’s lives, and bring together players from different portfolios and sectors to develop solutions

- support preventative, cost effective responses by building resilient communities and targeting investment based on what works locally

To improve how we work in place, we need to improve how we understand and talk about it

Government has a long history of engaging with communities and working towards local solutions. Across government, we work in different ways to achieve these goals. Yet we often use similar language to talk about different ways of working that have different objectives.

This framework describes a way of thinking about place that will enable us to effectively communicate across government

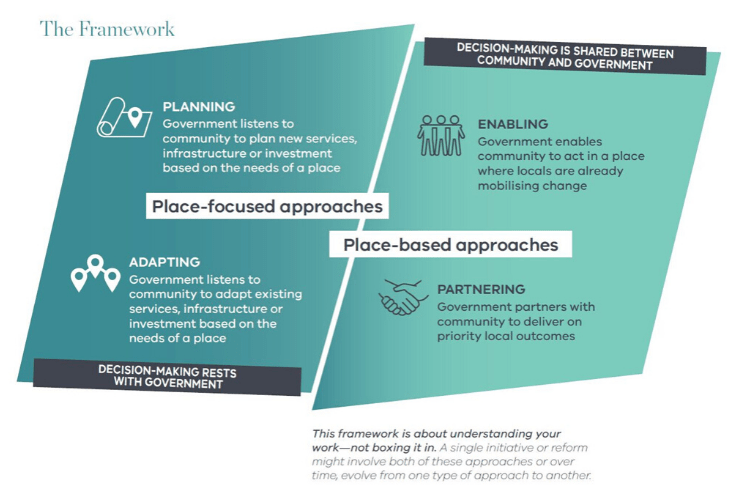

The framework clarifies the difference between approaches that invite local communities to inform or contribute to government decision-making, and those where we hand over control or are an equal partner in decision-making with communities.

The Framework

'Place-focused approaches' plan and adapt government services and infrastructure to ensure they are meeting local needs. Government listens to community to adapt how we do our business, but ultimately, has control over the objectives, scope and implementation.

'Place-based approaches' target the specific circumstances of a place and engage local people as active participants in development and implementation, requiring government to share decision-making. Place-based approaches can complement the bigger picture of services and infrastructure. They engage with issues and opportunities that are driven by complex, intersecting local factors and requiring a cross-sectoral or long-term response.

Both approaches are equally valuable ways we can engage with local context

Both place-focused and place-based approaches engage communities, pay attention to local needs and wants, and leverage the passion and expertise of local people. Neither approach is better or worse; rather, they are used based on local context and what will be most effective in achieving outcomes for a community.

This framework will delve deeper into place-based approaches

This framework defines and describes the two approaches, and then delves deeper into place-based approaches to explain how they can be designed and implemented, and how government can better support them.

Because we know that is where government needs to build its capacity

We know that government could be better set up to support place-based approaches. Place-based approaches push up against traditional ways of working and our standard systems and processes. Current policies and practices can hinder the collaborative, cross-government and relational work that is crucial for successful initiatives.

About this document

This section outlines the purpose, audience and structure of the Framework for place-based approaches.

Purpose

This framework is intended to:

- provide a common language for the different ways government works with local communities in places

- support clear communication within government and with community partners

- start a conversation about how government can better support place-based approaches that partner with local communities in decision-making

Audience

The framework is intended for Victorian public servants.

Structure

This paper will:

- define and describe the two ways that government works in place - ‘place-focused approaches’ and ‘place-based approaches’

- delve deeper into ‘place-based approaches’ and explain how they can be designed and implemented

- outline what needs to change in government to enable place-based approaches to succeed

While this framework does not go into depth on designing and implementing place-focused approaches, they remain a critical tool for government to achieve improved outcomes for local communities.

Inclusive and accessible engagement results in diverse voices being heard by decision-makers and the broader public.

Definitions

This section of the framework defines terms used within the Framework for place-based approaches.

What do we mean by the following terms?

Government?

By ‘government’ we mean us - the Victorian Government.

Community?

By ‘community’ we mean local people and organisations that live, work or operate in a place. This can include local people, businesses, service providers, associations, etc.

Place?

By ‘place’ we mean a geographical area that is meaningfully defined for our work.

For broader work in place, such as regional development work, a place might be a departmental region or a larger area where economic, social or ecological trends interact and play out.

For more localised initiatives, a place might be a local government area, a suburb or an area that crosses these types of administrative boundaries but where locals feel connected to or affected by what happens there.

Places and boundaries recognised by Aboriginal Victorians and Aboriginal Traditional Owners may differ from those recognised by non-Aboriginal Victorians and may cross accepted non-Aboriginal boundaries, including state boundaries.

Often, place is best defined in collaboration with local people to ensure it is a geographical area that is meaningful to them on a social, economic or environmental level.

Power?

By ‘power’ we mean the ability to control or influence, or be accountable for, decisions and actions that effect an outcome throughout the design, implementation and evaluation of programs or initiatives.

The systems and structures that produce or reinforce power are complex and shifting these is difficult.

Sharing decision-making control, influence and accountability?

We, as government, can share control, influence and accountability with community by partnering in decision-making with local people and organisations. This can happen, for example, through:

- collaboratively defining outcomes and objectives

- active participation in governance groups

- flexible funding that allows for local decision-making

- control over design and ongoing implementation

- designing evaluations and the process for incorporating learning

When we share or devolve control to community, we should be clear about our tolerance for risk and supporting accountability

Place-focused approaches?

‘Place-focused approaches’ tailor government services, infrastructure and investment to ensure they are meeting local needs.

They involve listening to community to understand how we can meet their needs and keeping them informed throughout design, implementation or evaluation.

Place-based approaches?

'Place-based approaches' target the specific circumstances of a place and engage local people from different sectors as active participants in development and implementation.

They can happen without government, but, when we are involved, they require us to share decision-making with community to work collaboratively towards shared outcomes.

Introducing the framework

This section introduces the framework, why a focus on place is beneficial and why a framework.

Why place?

Place affects the lives and outcomes of Victorians. By applying a place lens, we can support whole of government and whole of community responses to interconnected factors at a local level.

The places where we live, learn, work and play shape us

Victoria is made up of different places, each with their own unique built environments, social networks, economic conditions and people. These all affect how connected and supported people feel in their community, as well as how their lives are impacted by broader trends.

Evidence shows a person’s postcode directly affects their outcomes in life. The place where someone grows up and lives influences their health and wellbeing, as well as their access to opportunities.

Many opportunities and challenges are concentrated in place

Government has a strong growth agenda investing broadly in communities right across the state. This means there are opportunities in communities to leverage our investments to create better outcomes for local people.

Equally, many challenges are concentrated in places: communities can face multiple issues that intersect in a local area and require holistic responses that leverage the knowledge and skills of local people. All people live in places, contribute to places and are affected by places

Government needs ways of working that focus on place

Portfolio and departmental structures mean that we often focus our effort on one need, problem or population group at a time. Unfortunately, these top-down or centrally led approaches often miss opportunities and issues that are influenced by local contexts.

As a result, our current interventions and investments in disadvantaged places can be ineffective - with an increasing divide between many

disadvantaged places and the wider population.

We need approaches that span organisational boundaries and sectors to deal with causes, rather than problems. Working in place is one of these approaches.

" All people live in places, contribute to places and are affected by places." Griggs, J., Whitworth, A., Walker, R., McLennan, D., & Noble, M. (2008). Person or place-based policies to tackle disadvantage? York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Using place a frame of reference helps to do the following

Support civic engagement

Place-based approaches focus our effort and intention on communities and their strengths.

By working in place, we can:

- unlock the knowledge and passion of local people

- provide a meaningful forum for local agency

- enable communities to apply their skills and knowledge and have a sense of ownership over the decisions that are made

- build community connectedness and resilience

Think holistically and systemically

Focusing on place can help us ensure evidence-based policy decisions are implemented effectively across different local circumstances.

Thinking about how government comes together in a place:

- is a helpful frame for understanding how systems interact with and impact on people’s lives

- supports policy-makers to think differently about how government levers link and how we can bring together a different, or more holistic, group of stakeholders

- starts to break down the barriers between sectors and portfolios to drive new solutions to local issues

Support preventative, cost-effective responses

By building resilience and protective factors across the whole community, working in place supports government to focus on preventative responses, rather than crisis responses for individuals.

Targeting responses based on what works locally can support us to direct our investment where it will be most effective and have the greatest impact.

"Programmatic interventions help people beat the odds. Systemic interventions can help change their odds." Weaver, Liz (2019). The Journey of Collective Impact: Contributions to the Field from Tamarack Institute. Friesenpress. Karen Pittman, CEO of the Forum on Youth Investment

Why a framework?

Across government, much of our work is delivered at a local level. But not all this work is the same:

- Place-focused approaches use community input to improve how we do our business

- Place-based approaches add to this by sharing decision making with the community

This framework is designed to help public servants clarify the difference between approaches and support us to clearly communicate about

our work within government and with communities.

Government works in place in different ways

Government has a long history of engaging with communities and working towards local solutions. But, across government, we work in

different ways to achieve this.

‘Place-focused approaches’ involve planning and adapting our services and infrastructure with a focus on the needs of places. It is a tried and tested approach that ensures government services meet local needs.

But ‘place-based approaches’ are different. Place-based approaches can happen without government. But where we are involved, they go

further than government listening to community: they involve supporting local people and organisations to partner with us in decision-making.

Place-based approaches require us to let go of control and accept a level of uncertainty around priorities and implementation, as we work together with local partners to determine how to achieve shared outcomes.

Naming these different ways of working can help us work better together

Each approach is used for different reasons and is suited to different circumstances. There is no one right way to work in place - but different

approaches require particular skills and capabilities.

Understanding the difference between ‘place-focused approaches’ and ‘place-based approaches’ allows us to be clear about when we are inviting community to inform government decision-making versus when we are being an equal partner or handing over control in decision-making with community.

Recognising where we need to build capability

By recognising the different skills and resources required for working in place, we can identify where we need to improve. While we have strong

capabilities in listening to community, the things we need to support place-based approaches are not yet as systemically embedded

across government.

How can I use this framework?

Policy and program staff, managers, executives and decision-makers are encouraged to use this framework as a starting point to:

- reflect on current practice and your own role in working in place with communities and other parts of government

- consider and explore what opportunities there may be for you to work differently with communities and more collaboratively with cross government colleagues

- think about the influence you have supporting others in your organisation, or the broader system, to work in these ways

- find resources to support you to work better in place

The framework

This section delves into the framework and explains place-focused approaches and place-based approaches.

A whole of government framework for understanding place-based approaches

This framework provides a common language for different ways of working in place.

It supports clear communication within government and with the community about what we are trying to achieve and how we will go about it.

The framework is not intended to box your work into a single quadrant. Instead, it describes how different ways of working with communities

are appropriate for different circumstances.

Working well in place means being responsive to the needs of the local community—starting at the local context and shifting your ways of working as the context changes.

This means a single initiative or reform might involve more than one of these ways of working and, over time, will often evolve from one to another.

The Framework

Place-focused approaches

Place-focused approaches tailor services, infrastructure and investment to ensure they are meeting local needs.

They might involve collaborative practices like co-design or advisory groups, but ultimately, government has control over the objective, scope and implementation.

What are place-focused approaches?

Government delivers many services, infrastructure and investments in local communities.

Place-focused approaches recognise this and engage with communities to understand how the design and delivery of these activities can best meet their needs.

Across the Victorian Government, it is best practice to ensure our work is meeting the needs of local communities.

By engaging communities to understand how services and projects can work best for them, we can improve the effectiveness and outcomes of our support and investment.

When should you use a place-focused approach?

This approach can be applied to any government service, infrastructure and investment. We might use them where:

- a broader issue or trend is impacting different communities in different ways

- we know we have the tools at our disposal to respond effectively with government service delivery, infrastructure or investment

- community input or developing a shared understanding of local conditions would improve the effectiveness of a planned service response or infrastructure project

- community is willing and can be supported to participate in consultation and design processes

Who is involved?

- Government leads the process and is in charge of its design. Government is also in control of implementation, either by directly delivering services and initiatives or through funding and reporting requirements.

- Community is consulted and involved in the process. Their needs guide the design and ongoing implementation of services and infrastructure. They may share their views through consultation processes, co-designing elements of a project or sitting on advisory groups.

- Local government is a critical player and may inform or partner in design and delivery in local areas.

- Traditional Owners should be meaningfully engaged throughout the process and enabled to make decisions in accordance with principles of self-determination.

- Other stakeholders such as service providers, businesses and philanthropy are engaged as required depending on the needs of the project.

How does government use place-focused approaches?

There are two main ways that government ensures its activities are meeting local needs: planning and adapting.

Planning

Government listens to community to plan services, infrastructure or investments based on the needs of a place.

Used when there is an area in the state that is experiencing, or will experience, significant demographic changes, or will host major infrastructure of investment projects.

Case studySunshine Planning PrecinctSunshine |

|

Government’s major rail investment in the Sunshine area presented an opportunity to engage with community to plan new infrastructure and services that optimise investment and support social and other economic outcomes. Government consulted with the City of Brimbank, as well as local education and health providers, to develop an Opportunity Statement outlining the intent to make Sunshine an area of strong job growth and high-quality and affordable housing. A roadmap is being developed within government with implementation options for core planning, investment, social inclusion and value capture. Place-based approaches will also be important to guiding delivery and implementing the precinct plan. With the release of a public statement in 2020, broader stakeholder and community engagement will inform planning and may reveal opportunities for government to partner with community or enable community action. By tailoring government infrastructure investment to community needs and the local environment, the Sunshine Precinct is a good example of place-focused planning. Successful delivery of this precinct will involve ongoing collaboration with community, industry and landowners and businesses. |

Case studyCommunity bushfire planningStatewide |

|

Almost a third of Victorians live in regional areas, and the number of visitors to the state’s coasts and rural areas is growing. This exposes more people to bushfire risk. Managing this is an ongoing and shared responsibility, with the best decisions are shaped by the people they affect. Safer Together combines knowledge and experience of local communities with the expertise of fire and land agencies, to plan the most effective ways to reduce fire risk across all land tenure. Community First Projects are building capability of land and fire agency staff, providing eight community-based bushfire management officers working across 22 communities to:

This planning and engagement occurs all year round and provides communities with greater input over where and when planned burning should occur. As a result, firefighters are better able to work with local communities, land and fire agencies and ensure their activities to reduce risk are complementary. These activities are a good example of place-focused planning. They involve local community members so they have a greater say on how to reduce the risk of bushfire, including where and when planned burning should occur. Likewise, the activities seek to promote bushfire risk management as an ongoing and shared responsibility by leveraging the knowledge, experience and understanding that communities hold. |

Case studyLevel-crossing removalsStatewide |

|

Government is removing 75 dangerous and congested level crossings across Melbourne by 2025. The project will improve safety, create jobs and reduce travel time around our city for public transport users, pedestrians, The project is benefiting from extensive community involvement in planning. This can be seen in the design of the rail bridge to remove all level crossings between Bell Street in Coburg and Moreland Road in Brunswick. The design will create 2.5 km of public parkland and open space, with artist impressions reflecting local feedback collected from survey responses and drop-in sessions. Level crossing removals are a good example of a place-focused approach to planning. Community members help to shape the implementation of a major government infrastructure project by being consulted with and invited to share their views on how this will affect their local area.

|

Adapting

Government listens to community to adapt existing services, infrastructure or investment based on the needs of a place.

Used when a local area has a specific need that services or infrastructure can help meet, and tailoring to local context can improve the effectiveness of government's response.

"At the heart of all successful place-based partnerships are communities that provide maximum practicable input in all decision-making."

Case studyThe Orange DoorStatewide |

|

The Orange Door is a free service being rolled out across the state. It is for adults, children and young people who are experiencing, or have experienced, family violence and families who need extra support with the care, development and wellbeing of children. The statewide concept and service model outlines the functions of The Orange Door, but has been developed to allow for local tailoring and flexibility for continued improvement and development. In addition to statewide oversight and consultation, local engagement and governance mechanisms inform the establishment and operation of The Orange Door in each area. The Orange Door is delivered through a partnership between government and local community service organisations. People with lived experience of the service system (including victim survivors of family violence) informed the development of the statewide concept and service model, and understanding of client experience informs the ongoing improvement of the service offering in each area. The Orange Door is a good example of adapting, because the service has been designed to provide for a consistent level of service statewide as well as local adaptations. As The Orange Door is rolled out, Family Safety Victoria is learning more about the challenges and strengths of implementing an adaptable model which can be leveraged by other areas of government. The 2018 evaluation of The Orange Door found that there were opportunities to clarify operational issues where statewide standardisation is needed, and what can be localised for each area. The evaluation also advised that Family Safety Victoria becomes a more overt system steward to lead The Orange Door through the implementation phase. Family Safety Victoria is working with partners to strengthen consistency across workflows, processes and practice in The Orange Door. |

Case studyLearning places and education plansStatewide |

|

In 2016, the Department of Education and Training (DET) introduced the Learning Places model, which was established within 17 areas that align with local government areas across DET’s four regions. Under the model, schools, early childhood services and training organisations work on local outcomes with regional DET offices which link to DET’s central office and relevant service providers. In doing so, Learning Places facilitates cross-government initiatives and integrated service provision. The service delivery model allows localised, tailored and integrated decision-making, service and support partnerships and community central to improving the education system. Place-Based Education Plans, in seven communities across Victoria, support the Learning Places model and enable the department to collaborate with local communities and education partners to transform local education outcomes in areas with complex challenges. These strategies, particularly the Education Plans, are a good example of adapting universal service delivery. They have been designed to draw on and adapt to local contexts, so they can be applied to diverse communities across Victoria. In delivering the plans, DET is learning more about the challenges and strengths of implementing an educational model that can be adapted to the unique challenges and priorities of a local community - which can be leveraged by other areas of government |

|

Case study DELWP community charter Statewide |

|

The community charter of the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) The charter’s commitments set out what individuals and communities can expect from the department. Its commitment to ‘be available’ includes working with a place-based community focus by engaging with and being visible in local communities. DELWP is also committed to respecting the way communities want to work with them and adapting their approach to local needs. Through the charter, DELWP recognises and harnesses Victorian communities in delivering services to support liveable, inclusive and sustainable communities and thriving natural environments. The charter is demonstrated through the Loddon Mallee Climate Change Adaptation program. In this program, local communities will develop and drive their adaptation actions and strategies by participating in a range of initiatives designed to forge strong partnerships and learning networks, including:

DELWP’s community charter is a good example of adapting the way government operates to respond to the needs and views of local communities. It demonstrates how DELWP will be visible in local communities and talk to community members where they live, work and play. The charter is the beginning of DELWP’s work to deliver services that support thriving environments and communities. It engages community members to communicate openly and honestly about their issues and aspirations. DELWP will work with communities to make sure the charter delivers at a practical level throughout Victoria, by inviting community feedback and hearing their experience, to make sure communities feel included and that they are part of the decision-making process.

|

Place-based approaches

Place-based approaches go beyond listening to the community to inform our business: they are initiatives designed around the specific circumstances of a place and enable local people and organisations to make decisions when defining, designing and implementing a response.

What are place-based approaches?

Place-based approaches target the specific circumstances of a place and engage the community and a broad range of local organisations from different sectors as active participants in their development and implementation.

They are focused on shared outcomes and, crucially, they require us to partner with local people and organisations when defining and working towards these outcomes.

When should you use a place-based approach?

Place-based approaches are not suitable for all circumstances— they should complement government services, infrastructure and investment when these levers alone cannot be effective in meeting

local needs. We might use them where an issue or opportunity:

- is multifaceted, complex and concentrated in a place

- cannot be addressed through services, infrastructure or investment alone—existing government initiatives have not had the desired impact

- does not have a clear solution and requires the active involvement of local people and organisations to discover and develop meaningful responses

- requires a whole of government or whole of community response

- requires a cross-sectoral response

- requires a long-term response.

Who is involved?

Community is the driving force. Community leads action or is an equal partner with government in designing and implementing an initiative focused on something that matters to them. They are supported to partake in decisions about design and implementation.

Government can partner with community or enable their leadership and action. Government provides resources, knowledge and connections to support the initiative.

Local government is an essential player partnering with community or as a key enabler to their leadership

and action. Its resources, knowledge and connections are important to support an initiative.

Traditional Owners should be meaningfully engaged throughout the process and enabled to make decisions in accordance with principles of self-determination.

To be truly whole of community, a broad range of stakeholders - different levels of government, service providers, academic institutions and philanthropic organisations - will be actively engaged in the initiative. Business and employers are often key partners who are well-connected with local communities and hold levers to boost local growth and employment, which have strong links to social, economic, and wellbeing outcomes that are key to many place-based approaches.

How does government support place-based approaches?

There are two main ways that government supports place-based approaches: partnering and enabling.

Partnering

Government partners with community to delivery on outcomes agreed locally.

Often used to enable collaborative responses to shock or trigger event in a local area (such as a natural disaster, economic change or emerging social issue.

May be used where there is a locally concentrated issue or opportunity, but community does not yet have the connections and resources to respond without support.

Case studyMetropolitan and regional partnershipsStatewide |

|

The Metropolitan and Regional Partnerships create opportunities for the community to influence local decisions and shape their future. The partnerships facilitate the identification of local priorities, before presenting these priorities to the Regional and Suburban Partnership Committee of Cabinet. The partnerships include representation from business, the community and all three levels of government. Coordinating government responses helps to improve the liveability, prosperity and sustainability of Victoria’s suburbs and regions. These partnerships provide a chance for government, business and communities to collaboratively drive change by identifying opportunities to improve social, economic and environmental outcomes. Healthy Heart of Victoria (HHV) is working to improve the health of people in the Loddon Campaspe region – the ‘heart’ of Victoria. HHV is supported by the Loddon Campaspe Regional Partnership, the Department of Health and Human Services and the six Loddon Campaspe Local Government Areas. Collaborative decision making has been central for HHV, resulting in a codesigned, community led initiative that is supported by an Implementation Framework. HHV brought together 96 people from 20 different organisations, with over 500 hours spent developing and undertaking workshops across the region. This resulted in a co-designed, regionally owned, implementation model with three components:

The Metropolitan and Regional Partnerships, and HHV, are a good example of partnering because they collaboratively respond to local issues and opportunities that communities identify themselves. Communities and government share decision-making authority to actively involve community members in delivering locally agreed outcomes which vary and are driven by local circumstances. |

Case studyOur placeAt 10 schools across Victoria |

|

Our Place is a place-based partnership approach to delivering education and family services to communities facing disadvantage. In 2012, the Colman Foundation partnered with DET and invested in Doveton College to deliver the Our Place model. Our Place seeks to integrate a school and early childhood centre with facilities where parents and families can access early childhood, school and adult education services. Delivery of these services is facilitated by the Colman Foundation and provides families with access to a range of education and support services at a single location. After eight years of implementation, the results at Doveton College are encouraging and include:

Based on the success of the Our Place model, DET has entered into a ten-year partnership with the Colman Foundation to deliver the Our Place model at 10 sites across Victoria. The Our Place model is an example of partnering, where the Colman Foundation works with the community and responds to the identified needs to deliver tailored support for children and their families. The model recognises that schools are at the centre of the community, and by working in partnership with local council and other service providers, creates an integrated community resource that supports children and their families to succeed. |

|

Case study Latrobe Valley Authority Gippsland |

|

The Latrobe Valley Authority (LVA) was established in November 2016 following the announcement that the Hazelwood Power Plant and Mine would close in March 2017. Initially, the LVA worked with the community to support immediate worker transition needs with planning in mind to improve economic, social and environment outcomes for the Latrobe Valley community. While maintaining a focus on job creation, the LVA is now moving toward region-wide, long-term strategic growth opportunities to set the region up for a strong future. For example, the LVA has adopted a Smart Specialisation strategy to support the Gippsland region to identify key growth sectors and implement a strategic approach across food and fibre, new energy, health and wellbeing and visitor economy. By encouraging collaboration and innovation, the LVA has improved business conditions to bring more jobs to the region and build infrastructure that meets community needs (and creates jobs in the process). This collective work has already resulted in more than 2,500 new jobs and helped generate more than $99 million of private investment in the Latrobe Valley. The LVA is a good example of partnering because it draws on the best ideas and aspirations of those who live in the region and drives coordinated action across all levels of government to achieve shared outcomes. By listening, learning and understanding the local community, the LVA has instilled local pride and ownership and evolved how it works over a 4 year period. The LVA work highlights the importance of partnerships and building relationships at the local level, in response to a trigger event, to design and deliver meaningful outcomes for the region’s future. As community readiness and capacity grows, there is an increasing focus on how the government’s role evolves from supporting implementation to enabling the community to lead on prioritising its key needs. |

Enabling

Government enables community to act in a place where locals are already mobilising change.

Often used where a community is leading change towards an outcome that aligns with government priorities and government support can meaningfully assist the initiative to achieve its objectives.

" At the heart of all successful place-based partnerships are communities that provide maximum practicable input in all decision-making." Centre for Community Child Health, Royal Children’s Hospital

Case studyCommunity support groupsDandenong, Melton and Wyndham |

|

Community Support Groups (CSGs) work with culturally specific communities to strengthen services for individuals who may be at risk of youth disengagement or antisocial behaviour. Local conditions influence the CSGs, which are funded by government to:

The CSGs also build capacity to make services more culturally appropriate and responsive to the needs of the communities with which they work. The CSGs vary in their emphasis between locations, but all use community-led, place-based prevention and early intervention approaches to build protective factors to support young people and mitigate against early factors that lead to youth disengagement. Government funds community-led auspice agencies, staffed by community members, to oversee the day-to-day operations of the CSGs. At each site, Local Reference Groups (LRGs) advise the auspice agency and help to develop and prioritise activities and programs. LRG membership includes community members and government representatives from relevant departments/agencies. CSGs exemplify enabling—the flexibility to work with communities and on their priorities. CSGs provide an example of how government, alongside local leadership, can find opportunities to meaningfully assist community initiatives that are already underway. |

Case studyCommunity revitalisationFlemington |

|

The Flemington Works project was established through the support of the Victorian Government to tackle complex, systemic barriers to employment and economic participation for Flemington public housing estate residents - particularly women and young people - who experience some of the highest levels of social and economic disadvantage in Victoria. Delivered by the Moonee Valley City Council (MVCC), the project works with residents who are active participants in co-defining issues and co-designing and delivering solutions. Activities are coordinated at the Community Centre, which facilitates support services and social events. The approach emphasises building relationships, networks and trust to establish community-led, long-term responses to entrenched social and economic exclusion. Initiatives to support pathways to employment, micro-entrepreneurship and community leadership have been complemented by collaboration with local industry and Jobs Victoria. The project has also driven a significant change agenda to reform the council’s social procurement and recruitment processes. Flemington Works also exemplifies enabling because it actively involves communities in co-defining, co-designing and delivering solutions to improve economic participation. Flemington Works is an example of how state and local government and communities can draw on local knowledge, strengths and relationships to address significant and geographically specific social and economic disadvantage.

|

"Place-focused approaches work when we know what the answers are. When faced with complex challenges and when we don’t know the answer, place-based approaches offer a platform for finding these solutions together." Centre for Community Child Health, the Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne (2011). Policy brief: Place-based approaches to supporting children and families.

Case studyGunaikurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal corporation |

|

In 2010, the Victorian Government committed to collaborate with Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation (GLaWAC) to establish a natural resource management (NRM) and cultural heritage enterprise to be owned by GLaWAC and to employ Gunaikurnai People to work on Aboriginal title and other lands. The government worked with GLaWAC to develop and implement business and marketing plans, establish a separate legal entity and to incubate the Gunaikurnai NRM and cultural heritage enterprise. GLaWAC has led significant cultural training, recruitment and retention programs which requires the investment of time and resources. GLaWAC has also worked hard with partners to improve procurement processes. The NRM enterprise is now commercially viable and employs Gunaikurnai and other Indigenous persons. GLaWAC and the Gippsland Environment Agencies (GEA) are signatories of a Partnership Agreement to commit to work together towards shared objectives and mutual opportunities that meet respective goals. They share four common objectives:

GLaWAC and GEA agree that to achieve these shared objectives, they will work together to share strengths, build opportunity and develop close working relationships that benefits all partners. All 14 signatories to the Partnership Agreement commit to an annual planning cycle and an individual partner action plan with quarterly meetings, regular review and open communications. The partnership between GLaWAC and the GEA is a good example of how communities that already mobilising for change can be enabled to work towards a shared outcome with government. The GLaWAC play a key role in decision during quarterly meetings, where they and several government and community groups in the area can plan and review the actions they are jointly taking. |

Place-based approaches in action

This section illustrates place-based approaches in action, designing place-based approaches and explains how to design and implement place-based approaches.

Designing place-based approaches

Place-based approaches are not for the faint-hearted - they require the right mix of capabilities, mindsets, policies and resources from both community and government.

All successful place-based approaches share a commitment to collaboration and shared outcomes. But in practice, initiatives use different models, methodologies and strategies depending on the local context.

Every place-based approach is, by definition, unique to the place it is targeting

Place-based approaches share common characteristics that guide their design and implementation - they:

- respond to complex, intersecting local drivers that require a cross-portfolio and sectoral response

- develop a shared understanding of local context drawing on a broad range of evidence, from data to research to lived experience and local knowledge

- are based around shared outcomes that reflect locally agreed priorities and unite local stakeholders

- embed deep engagement and collaborative governance structures that engage across sectors and with a diverse cross-section of the community

- are implemented through shared action, with an iterative approach and progress monitoring that supports continual learning

- apply formal approaches to evaluation to enable accountability and guide strategy

However, how partners want to (and are ready to) work will be different in each case.

This section will unpack some of the differences that arise when designing place-based approaches and will require consideration by government when considering or embarking on a place-based initiative.

This section will explore:

|

Different levels of readiness

Place-based approaches work best when communities and government share the right capabilities, policies, mindset and intent. Their success relies on shared outcomes and the strength of relationships.

To work together in a place-based approach, community and government need to be ready or willing to build readiness.Readiness can be gauged by looking at factors such as:

- Leadership

- Government and community leaders with connections, knowledge and influence who are willing to apply their resources to an issue and ‘model the message’ by collaborating.

- Connections

- Across community and government, existing relationships between people and organisations are a starting point for mobilising around shared outcomes.

- Mindsets and willingness to learn

- A willingness to work outside of traditional processes and across organisational boundaries; adapt to changing contexts; and continually innovate in pursuit of shared outcomes.

- Existing effort

- Existing programs, policies or actions around an issue or opportunity can demonstrate an ability to mobilise around outcomes and an attitude of awareness and empowerment.

- Knowledge of past efforts

- People who know what has gone before (and can identify what does and does not work in improving outcomes for the local community) are key to ensuring that initiatives build on lessons learnt.

- Resources and skills

- Staff, time, funding, facilities, skills, etc. in the community and within government that can be made available to work towards shared outcomes are a key enabler.

Satisfying all of these conditions is not common, and when working in a place-based way, you always need to start where government and the community are at.

Government can be uncomfortable with the time it takes and the process of sharing influence, control or accountability. Staff often do not have the right mix of capabilities and mindset or feel appropriately authorised to engage effectively.

Communities also might need to build the skills or leadership to stay the course.

When this is the case, partners can be supported to build readiness through capability-building, community-strengthening activities or, as a starting point, more partnered approaches.

Different supporting teams or organisations

All successful place-based approaches will be led by a collaborative governance group, with clear terms of reference that ensure representation from across the community.

All kinds of governance benefit from diversity—this is especially true when working in a place-based way. When establishing a governance group, conscious effort should be made to include a range of voices in a community, rather than replicating existing power structures or only engaging the ‘usual suspects’.

All governance groups should include Aboriginal leadership.

Place-based approaches also require a structure, team or organisation to support the governing group and coordinate the work (sometimes referred to as a ‘backbone’).

Different place-based initiatives will choose different homes for this coordinating function, depending on who is best-placed with the readiness, connections, drive and resources to take on the role.

Following are some examples of potential homes for supporting teams, and how government can support them.

| Government team |

| Involves - establishing a new or using an existing state government team or authority. |

|

Best suited to issues or opportunities where state government:

|

| Example Latrobe Valley Authority. |

This model is housed within the Victorian Government, and the types of resources it might require include:

|

|

Community organisation team |

Local government team | Coalition team |

|

|

|

|

Best suited to issues or opportunities where community:

|

Best suited to issues or opportunities where local government:

|

Best suited to issues or opportunities where:

|

|

Example The Centre for Multicultural Youth and the Wyndham Community and Education Centre are the auspice organisations for Community Support Groups. |

Example The local council coordinates and delivers the Flemington Works project. |

Example Tasmania’s Burnie Works initiative is supported by a distributive backbone support team with members from government, non-government and business sectors. |

These models are led by partners outside of the Victorian Government. Government can support them by providing:

|

Different methodologies, models and tools

The most effective place-based approaches involve a diverse group of stakeholders coming together to work towards shared outcomes.

Collaborative approaches support and guide people to achieve change, with an emphasis on agile and adaptive ways of working to support cycles of small-scale testing and learning.

When collaborating to achieve change, government partners contributing to place-based approaches can draw on a broad range of methodologies and tools—whether established or newly developed.

Identifying the most suitable methodology and tools depends on purpose, context and objectives. Place-based approaches may draw

primarily on one of them or use a mix to achieve agreed goals.

Because there are many ways to implement place-based approaches, these can be used to guide effort depending on the phase of work the place-based approach is in. Methodologies that offer a structure to guide the implementation through the different phases of collaborative place-based work include:

- Collective Impact Framework

- utilised for population-level change outcomes

- Smart Specialisation Strategy—

- utilised for regional development outcomes

- Asset-based community

- development—utilised for local community-level strengthening

A number of models and tools are available that can support ways of working and provide mechanisms to enable the place-based approaches to achieve agreed priorities include:

- Systems change

- Adaptive cycle

- Co-design and human-centred design

Policy designers can draw on these options as they work with local stakeholders to identify those that are best suited to the local context and desired level of change.

This will involve engagement with different groups and communities, based on the demographics of the local area, to understand their experience of place, and ensure activities will support their needs. It is critical that methodologies, models, tools and engagement approaches are tailored to meet the unique needs of diverse community members, including Aboriginal Victorians, people from culturally and linguistically diverse communities, people with disabilities, children and young people, older people and LGBTQI people.

Victoria’s Public Engagement Framework, which is being developed, can be used as a tool to promote inclusive engagement.

Different ways of sharing decision-making influence, control and accountability

Government could share decision-making, influence, control and accountability—it is important to consider not just how but why.

Community having some authority within the initiative is a defining feature of place-based approaches. Central to their success are shared objectives, accountability and partnership.

An awareness of the structures and systems that produce or reinforce power (including governmental power) is key to doing this work well. Power-mapping can be a useful tool to help you.

When and how will vary according to government’s appetite for risk and local partners’ capacity or readiness. It is important to note these might change throughout the life of the initiative.

Throughout an initiative, government needs to continually interrogate if we are sharing the right level of decision-making, influence, control and accountability and if we are sharing them in the right way, for example by asking:

- Are the people with the most knowledge and expertise supported to decide how to engage with an issue or opportunity?

- Are Aboriginal Victorians and communities being empowered consistent with the principles of self-determination and the Victorian Government Aboriginal Affairs Framework and the Self-Determination Reform Framework?

- Is partnered decision-making supporting stakeholders to progress towards an outcome?

"Collaboration…comes with uncertainty, and it requires decision-makers to share power and be open to sharing data, lessons and failures". Centre for Public Impact (2019). The Shared Power Principle: How governments are changing to achieve better outcomes.

Self-determination and place-based approachesThe Victorian Government is committed to advancing Aboriginal self determination through systemic and structural transformation. This commitment is articulated through the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework 2018–2023 and the Self-Determination Reform Framework. The Victorian treaty process marks a new era of governing and policy making in the Victorian Government. It will require public servants to work in new, collaborative and innovative ways to support Aboriginal self determination to create fundamental change for Aboriginal Victorians Place-based approaches can be a key tool for the Victorian Public Service to enable self-determination as they support the transfer of power and resources to Aboriginal communities and organisations to pursue their economic, social and cultural priorities. With commitment from government to reform its systems and structures to support self-determination, place-based approaches can support Aboriginal communities and organisations to define and work towards priorities and outcomes that reflect community aspirations. Place-based approaches do not inherently empower Aboriginal Victorians. We must consciously incorporate principles of self-determination to ensure these approaches include Aboriginal Victorians and recognise their unique and enduring connection to place as the Traditional Owners of Victoria’s lands and waters. Place-based approaches should commit to inclusive engagement and include self-determination as a guiding principle, regardless of the outcome or model identified. |

"Change happens at the speed of trust...Working, trusting relationships at every level is key to these initiatives...Trust is built through principled action that demonstrates people do what they say and through people seeing outcomes." The Australian Centre for Social Innovation (2019). Place-based collective impact: Framework for Practice.

Implementing place-based approaches

Place-based approaches take time and patience—they do not follow a traditional program or policy cycle.

In practice, place-based approaches are cyclical journeys that move at the ‘speed of trust’

Place-based approaches differ from traditional program or policy development processes: they focus more on building readiness and creating shared outcomes that will enable collaborative implementation.

Table 1 outlines a typical process of how a place-based approach might play out. However, this process is often not linear. Initiatives may cycle back to earlier phases to build readiness and shape a shared vision as new barriers are discovered or new partners come on board.

Furthermore, because place-based approaches often start within community, government may later join the process. For example, government might become engaged when community has developed a shared vision for change and is starting to plan for the resources and skills they will need to make it happen.

This is especially true of enabling responses, and requires us as government to focus on supporting initiatives, rather than shaping them.

Table 1: Typical process for developing and implementing a place-based approach

| 1. Identify if a community would benefit from a place-based approach |

Use in-depth local knowledge to assess if a place-based approach would be an appropriate response to local opportunities or challenges. |

| 2. Assess readiness |

Assess if a community is ready to or is already self-mobilising around an opportunity or issue, and if government is able to meaningfully contribute. This considers if the required resources, leadership, connections and mindsets exist—or if they could be built. |

| 3. Develop a shared vision for change | All community members and organisations with an interest come together to identify the change they want to make in the community. This is articulated with clear outcomes, measures of progress and impact and a plan for making it happen. |

| 4. Implement together | Local partners work with government and other organisations, such as business and philanthropy, to resource and implement the plan. A local collaborative governance group oversees the implementation and has the ability to make changes. |

| 5. Embed a culture of learning and continual improvement | All partners embed a culture of learning to bring in new ideas and keep the initiative effective and relevant. Evaluation enables them to assess if work is progressing shared outcomes, learn from failures and consider how practice and policy changes can be embedded into their organisations over the long term. |

| 6. Celebrate and communicate success | Everyone should be supportive of each other and ensure achievements are recognised and celebrated. |

The cyclical nature of this process, and the fact that place-based approaches are often responding to complex or intersecting factors, means the timeframe in which you would expect to see impacts may also differ from a traditional program.

Figure 2: Place-based approaches often take some time to demonstrate impacts. Adapted from: Dart, J. 2018. Place-based Evaluation Framework: A national guide for evaluation of place-based approaches, report, Commissioned by the Queensland Government Department of Communities, Disability Services and Seniors (DCDSS) and the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS).

| Late years 5–9 | Local population impact Sustainable positive outcomes are being observed in the whole of the community or the targeted cohorts (rather than specific users), showing how people’s lives or places have changed and inspiring others to become involved in the approach |

| Middle years 3–5 | Systemic changes in the community

|

| Initial years 1–3 | Enablers for change Things are being put in place (e.g. community priorities to direct investment; capacity building; transparent governance; an integrated learning culture) to enable an approach to create systemic change. |

| Set-up phase | Foundations The readiness of people to begin the change journey is being built. Because every initiative will start from a different point and require different foundations, the length of this phase will be different for each place-based approach but will take at least one to two years. |

|

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR MEASURING SUCCESS? Place-based approaches are often regarded as challenging to evaluate because they deal with complex issues over a longer-term period and with a broad range of stakeholders. Because place-based approaches encourage working across organisational boundaries and ensuring the locus of control is with the people best-placed to lead, they can also have a ‘popcorn’ effect: a great idea might ‘pop up’ because of the time and space a place-based approach has created (e.g. collaborative governance groups, facilitated exploration of shared outcomes), but it might end up being led by another group or initiative and, so, would not be directly attributable in a traditional evaluation context. However, it is crucial to thoroughly evaluate place-based approaches—to support a culture of continual learning and to ensure effort is translating into systemic change for people and communities. Evaluations should be designed to measure the appropriate type of impact over the lifetime of an initiative (as outlined in Figure 2). It is important to define the anticipated changes in community outcomes as well as the measures and datasets that will allow progress to be tracked. For example, in the initial years, measures of success might focus more on enabling conditions and processes—looking at whether strong governance is in place, partners are working collaboratively together, and flexible and innovative mindsets are being embedded. As the project develops, it is important to assess if these ways of working are translating into outcomes for individuals or specific cohorts. Over the longer-term, evaluation can show if an approach is embedding systemic change that improves outcomes for target cohorts or the whole community. Because place-based approaches actively engage the community, evaluations must also involve local partners in the design, collection of data and development of recommendations. To value and capture community voice, evaluations are also inclusive of different types of evidence, including cultural and local knowledge. |

What now?

This section delves into the key areas of change that government needs to explore to improve how it partners in place.

What needs to change in government?

Place-based approaches are being successfully supported across government, but this success is often dependent on the skills and tenacity of individual people and teams.

We need to change, systemically, how we fund, resource, learn from and support place-based initiatives.

Individual departments and initiatives across government are working with communities using

innovative place-based approaches.

But the preconditions for success are not yet embedded systematically across government, meaning initiatives are often implemented in isolation without their lessons being shared and translated into systemic change.

The Victorian Government is committed to building on our experiences, deepening our knowledge and understanding of place-based approaches and strengthening how we partner with communities through:

- culture, capabilities and leadership

- funding and resourcing

- information and learning

- effective and sustainable way to provide support

Culture, capabilities and leadership

For public servants to work in place-based ways, we need enabling mindsets that focus on collaboration, innovation and seizing opportunities.

Adaptive leadership and ‘change champions’ that support cross government work and innovation can unlock opportunities and break down bureaucratic barriers that restrict place-based approaches.

Currently, much cross-government work is supported by structures like interdepartmental committees. But we can also explore new ways of blending teams and creating an authorising environment for collaborative cross-portfolio work.

While culture and capabilities are important, we need to be cognisant of policy settings that enable cross-portfolio planning and implementation.

Funding and resourcing

Programmatic or siloed funding approaches counteract this work. Government needs to be flexible and innovative in how it resources place-based approaches. For example, by providing funding that is flexible at a local level, or by pooling funding with multiple departments and partners operating in an area.

Embedding models of shared accountability and reporting can also help overcome challenges associated with individual program funding streams.

Information and learning

To ensure place-based work is building on lessons learnt, government needs to make sure that data and evidence is in the hands of the people who need it and that they are supported to use it.

Powerful ways that government can support place-based projects include:

- embedding systems that support sharing of learnings

- supporting a culture of adaptive learning

- sharing data across agencies and with communities

- providing local data that is accessible and meaningfully communicated to local partners

Effective and sustainable ways to provide government support

To embed place-based work as part of everyday business, we need to better coordinate policy and practise capability within government, ensuring there are processes for initiatives to access required supports.