- Date:

- 5 Mar 2023

Introduction

Joined-up work

Although there are many definitions, ‘joined-up work’ is a term used to describe collaboration across organisations, industries, and sectors, to achieve a common goal. Joined-up work is not a new concept; it has been explored by a range of organisations throughout the world for some time. Governments at all levels have experimented with joined-up ways of working to deliver better responses to complex social and economic issues.

More recently, ‘boundary spanning’ is being used to describe collaboration across organisational and sectoral boundaries to achieve identified objectives (ANZSOG 2020).

For place-based approaches, joined-up ways of working are critical. The success of place‑based approaches is often dependent on the extent to which partners, stakeholders and government can work together to achieve positive outcomes and impacts for local communities. Place-based approaches require government to adopt bottom-up, collaborative, locally embedded and participatory ways of working.

This report

This report sets out the key learnings on joined-up work in the place-based context. It provides guidance and policy advice for Victorian Public Service (VPS) employees with a view to strengthen the culture, skills, and capacity of the VPS to effectively partner with place-based initiatives. It is intended to inform learning and to encourage constructive change.

The report draws on desktop research on joined-up government from Australia and overseas, as well as practice insights gathered through targeted interviews with VPS employees and a workshop with Working Together in Place learning partners.1

The report begins by exploring the various definitions associated with joined-up work and how these apply to different contexts.

It proposes a framework describing the supporting conditions needed for effective joined-up work, alongside practice examples of effective collaboration.

The report concludes with tools for further reference and a call to action for next steps.

Whole-of-Victorian-Government Place-Based Agenda

This report was developed as part of a Victorian Government Place-Based Agenda that was designed to strengthen how government partners with place-based initiatives to better support and enable the achievement of locally identified priorities. It focused on increasing the capabilities of the VPS and creating systems change within government in the areas of funding, community access to data, research, monitoring, evaluation and learning, and VPS culture and capability.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to VPS staff from the Latrobe Valley Authority, Department of Education and Training, and Department of Justice and Community Safety for your valuable contribution. Thanks to Cynthia Lim and Carolyn Atkins from the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions (DJPR), and Deb Blaber from EMS Consulting for sharing their experiences of joined-up efforts in past Victorian initiatives. Thanks also to Working Together in Place learning partners from Go Goldfields, Upper Yarra Partnership, Our Place Robinvale, Impact Brimbank, and the Mornington Peninsula Foundation for generously sharing their knowledge and insights.

1 The Working Together in Place initiative (WTIP) was established to identify how the Victorian Government can work better to support and enable communities through collaborative, community-led place-based approaches to achieved improved outcomes at the local level. The initiative was part of the government’s broader Whole-of-Victorian Government Place-based Agenda led by the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions.

Exploring the meaning of joined-up work

Definition of joined-up work

Although there is no universally accepted definition of joined-up work, the term is broadly used to describe ‘collaboration of public, private, and voluntary sector bodies across organisational boundaries towards a common goal’ (UK National Audit Office 2001).

The distinguishing characteristic of joined-up work is that there is an emphasis on objectives shared across organisational boundaries as opposed to working solely within an organisation (Victorian State Services Authority 2007).

Joined-up work can occur through formal and informal partnerships or through carefully and strategically structured governance arrangements. It also represents different ways of working, from interpersonal interactions to formal and interdependent arrangements based on mutual benefit and common purpose (Buick 2012).

For the purposes of this report, ‘joined-up work’ is defined as:

The coordination and collaboration of work by the VPS to support place-based approaches, and the authorisation to do so, both within government and with non-government partners, including communities.’

The terms ‘coordination’ and ‘collaboration’ have varied meanings depending on the context in which they have been used.

Continuum of horizontal engagement

The continuum below distinguishes the various forms of horizontal engagement that can occur among stakeholders: varying from informal and ‘lighter’ forms of engagement such as networking and cooperation, through to deeper forms of coordination and collaboration (Szirom 2014).

The depth and breadth of these engagements differ depending on how power, decision-making and resources are shared between stakeholders. While networking and cooperation can be considered as a form of joining-up, in line with the definition above, this report prioritises coordination and collaboration as most relevant for government when working with place-based initiatives.

Continuum of horizontal engagement (Halligan 2011)

Networking

- Characterised by informal relationships

- Information sharing for mutual benefit

- Minimal time and commitment

- No turf sharing

Cooperation

- Characterised by short-term informal relationships

- Information is shared as needed

- Authority is retained by each organisation

- Resources and rewards remain separate

- No turf sharing

Coordination

- Characterised by formal relationships and mutually compatible missions

- Common planning and joint decision‑making

- Clear division of tasks and roles

- Formal communication channels

- Stakeholders retain authority

- Resources shared between stakeholders

- Shared benefits and risks

Collaboration

- Characterised by formal, intensive, and longer-term arrangements

- Requires organisations to share power

- Shared resources, risks, benefits, and rewards in the pursuit of a common purpose

- Organisations operate inter‑dependently

- Joined-up structure, shared responsibility and mutual authority and accountability.

The way that stakeholders (from government and the community) approach collaboration (e.g. degree of formality, and level of collaboration) is influenced by various factors including (Weaver 2021):

- context of the community

- pre-existing relationships, connection, and trust between the partners

- history and experience with collaboration

- complexity of the problem or issue being addressed

- availability of resources to support the collective effort.

Organisational culture is fundamental to collaboration as it influences the willingness and readiness of staff, and how collaborative efforts are incorporated into organisational practice.

What is the purpose of joined-up work and when is it suitable?

Joined-up approaches have been promoted by various governments to overcome government silos and address competition between departments (Christensen 2007). At the same time, governments are increasingly adopting place-based approaches to address locational disadvantage in communities.

Attempts to join-up government have achieved some successes often in the areas of disaster management such as bushfires, cyclones, food relief efforts in response to COVID-19 lockdowns, and local initiatives that draw on the collective impact framework (e.g. GROW21 Geelong Regional Alliance, Logan Together, Hands up Mallee).

Joined-up work has been used in multiple contexts (Shergold 2004) - ranging from top-down decisions that require a cross-portfolio approach; local agencies working together to achieve shared goals for a community; or work spanning any or all levels of federal, state/territory and local governments in Australia.

Joined-up ways of working are not a panacea for all problems and may not be appropriate in all circumstances. However, joined-up work approaches can be used for the following purposes (State Government of Victoria State Services Authority 2007):

- to address complex, intersecting, and long-standing issues at the local/community level using place-based approaches/initiatives

- to improve outcomes for specific cohorts through multi-pronged strategies and an integrated approach across policy areas (e.g., health, housing, employment, justice)

- to improve accessibility, responsiveness to service user expectations, and improve efficiency of government through integrated service delivery

- to deliver cross-cutting policy solutions by working across portfolios and jurisdictions (local, state, and federal).

Why does joined-up work matter?

Joined-up ways of working can help governments to overcome unhelpful ways of working when partnering with place-based initiatives, including:

- A programmatic focus

- 'Top-down’ ways of working

- Lack of collaboration and information sharing with local communities

- Lack of authorisation to engage as an equal partner with a place-based initiative.

Case study: Hands Up Mallee

Taking a relational approach to emergency food relief

Hands Up Mallee (HUM) is a place-based initiative in Mildura that supports local responses driven by what the community needs and wants. During the initial lockdowns in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, HUM quickly created a joint approach to emergency food relief in response to the community’s food scarcity challenges.

HUM drew on their existing relationships to convene more than 16 organisations to pool resources. They strengthened the state funded food relief efforts by ensuring that support needs were tailored to the needs of culturally diverse groups.

By the end of the lockdown period between March and November 2020, 3,354 people were supported through nearly 900 immediate food parcels, 171 activity packs, and 194 referrals between organisations.

Joined-up ways of working within a place-based context

Joined-up work is already undertaken daily throughout the VPS, including through existing partnerships with place-based initiatives. However, government’s centralised approaches, including centrally determined targets and top-down performance management, can sometimes present barriers to joined-up work (O'Flynn 2011).

Real and lasting system change will require agencies to shift priorities to embrace the notion that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts and that ‘system trumps agency.’

(Davison 2016)

This chapter outlines the supporting elements needed for better joined-up work so that government can meaningfully partner with communities to drive sustainable outcomes for local communities.

Supporting conditions for joined-up work

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to joined-up work. There needs to be variety of mechanisms and processes to facilitate collaboration (Shergold 2004). However, the research confirms that there are key supporting conditions capable of supporting good practice joined-up work.

Supporting conditions and mechanisms for achieving them

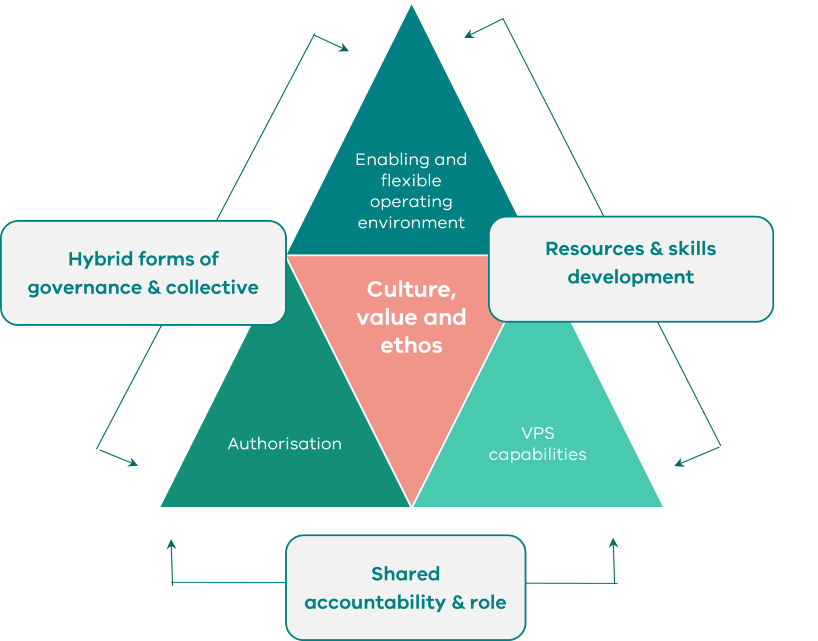

The framework in Figure 1 identifies three interconnected elements that are necessary conditions for joined-up work, as represented in the inner triangles of the pyramid:

- An enabling and flexible operating environment that supports new ways of working

- Supportive authorisation to undertake joined-up ways of working

- Capabilities of VPS staff to confidently engage in joined-up ways of working.

The remainder of this report is structured around these supporting conditions and will touch on the mechanisms required to achieve them. These are represented in the outer boxes of the pyramid in Figure 1 below, and are:

- hybrid forms of governance and collective leadership

- resources and skills development

- shared accountability and role fluidity.

Finally, the central triangle indicates that an enabling culture, values and ethos is essential for enabling joined-up ways of working to flourish.

An enabling and flexible operating environment

As outlined above, joining-up across government and communities can occur to various degrees and in various ways.

A supportive and flexible operating environment is necessary for effective cross-collaboration as it can re-shape incentives and enable behavioural change in the VPS (Marsh 2017). As illustrated in Figure 1, collective leadership, hybrid forms of governance and adequate resourcing accompanied by skills development (for collaborative ways of working) are needed to create a flexible environment for better cross-collaboration within government and with community stakeholders.

Inflexible top-down structures can constrain the capacity of staff to respond effectively and in a timely manner to changing community needs.

Factors that contribute to an enabling and flexible operating environment include:

- tailored and flexible funding that facilitates opportunities for VPS to develop sustainable relationships with stakeholders

- careful balancing of horizontal accountabilities (joint action, common standards, shared systems) with vertical accountability for individual agency performance

- supportive communication and information sharing infrastructure

- new accountabilities and incentives for staff to engage in joined-up ways of working across government and with communities (e.g. ensuring that cross-agency targets are equally as important as agency-specific targets)

- introducing performance measures that recognise the value of relational and collaborative work undertaken by VPS.

While top-down approaches are important to set priorities and push through joined-up ethos, cooperative relations on the ground may prove to be more important in the long-run. (Keast, 2011 p.229)

Authorisation

As illustrated in Figure 1, authorisation is initiated through hybrid forms of governance and collective leadership as well as shared accountability and role fluidity. An overview of each – and how they link to effective authorisation – is provided below.

Without careful attention to, and investment in, creating [supportive] architecture, most attempts at joining-up government are doomed to fail, as the power of embedded ways of doing things restrains innovation and undermines cooperation. (O’Flynn 2011, p.11)

Governance

Governance is built on factors such as accountability, obligations, authorisation and delegations in decision-making, effective risk management, and values among others (Victorian Public Sector Commission 2015).

There are two important and inter-related aspects of governance that impact on the effectiveness of place-based approaches: the governance structures of the PBIs themselves, and the ‘governance of government’ in the context of place-based approaches (Australian Social Inclusion Board, 2011).

Place-based approaches require governance mechanisms that (Marsh 2017):

- are collaborative

- share accountability

- are tailored to local context

- enable genuine power sharing

- enable meaningful community involvement in decision-making.

There also needs to be flexibility to evolve over time to reflect different stages of work, new learnings, shifts in context, and changes to membership (Byers 2011).

Despite the well-known barriers encountered by place-based approaches partnering with government, little attention is paid to the role of the governance of government and how it influences outcomes of place-based approaches (Alderton 2022).

Effective joined-up work within government requires multiple horizontal efforts (sometimes also including place-based initiatives) that are supported by strong vertical mechanisms (Christensen 2007). However, a key challenge associated with such hybrid forms of governance is the tension between multiple and conflicting accountabilities—horizontally across partners and vertical accountabilities of staff within their agency (Ferguson 2009).

Partners must negotiate between multiple accountabilities, priorities, constraints, interests and manage risks across departments, sectors and the community who share responsibilities for decisions and outcomes within place-based initiatives.

Reaching consensus and deciding what is feasible will require navigating and negotiating with existing systems through intermediary processes. ‘Navigating the middle’ (see Figure 2 below) between top-down and bottom-up processes involves shaping top-down issues so that they are context sensitive and systemically tapping into local knowledge on the ground and feeding them back up to the centre (McKenzie 2020).

Balancing these tensions requires performance measures and accountability structures that support and reward horizontal and vertical targets including shared outcomes, instead of outputs (State Government of Victoria State Services Authority 2007).

Key factors to consider when setting up collaborative place-based governance arrangements (Emerson 2012):

- Contextual factors

- political dynamics and power relations, within communities and across government

- degree of connectedness and relationship maturity and quality among stakeholders

- levels of trust and impacts on working relationships across stakeholders

- resourcing conditions

- policy/regulatory/administrative frameworks and procedures

- prior failure, to address issues through traditional/standard processes and mechanisms.

- Drivers of collaboration

- incentives, such as resourcing needs and opportunities, situational/institutional crises that require joined-up action/solutions and stakeholder interests

- inter-dependence, when organisations are unable to achieve objectives on their own

- addressing uncertainty, addressing challenging social problems that require groups to collaborate to reduce, diffuse and share risk

- collective leadership, for influencing, securing of resources and solution brokering.

Case study: The Geelong Aboriginal Employment Taskforce

Example of a model of collaboration between government and community

As part of the Geelong targeted employment plan, the Geelong Aboriginal Employment Taskforce (the Taskforce) brings together senior Aboriginal, community, public and private sector leaders to drive positive change in the region. DPJR supports the work of the Taskforce by facilitating strategic opportunities to improve employment and career development for Aboriginal people living in Geelong.

The Taskforce is providing a model for how government can come to the table in a collaborative way to build stronger accountability in delivering inclusive economic outcomes based on the needs of local communities

To date, this includes identifying ways to optimise Jobs Victoria services in the region and to support Aboriginal people, business and wealth creation through the Victorian Aboriginal Employment and Economic Strategy, Yuma Yirramboi. A priority of the Taskforce is the development of a Geelong Aboriginal Public Sector Employment Strategy. The strong partnership between DJPR and the Taskforce is driving robust accountability through senior executive representation from Geelong-based public sector employers and across the VPS.

Moving forward, DJPR intends to actively engage the Taskforce to ensure that the local Aboriginal community and business sector derive strong economic benefits from an unprecedented period of investment in Geelong. This includes leveraging opportunities through the Social Procurement Framework as part of Victoria’s Big Build and in the lead‑up to the Victoria 2026 Commonwealth Games.

Cross-boundary governance models

There are various governance models or arrangements that can be adapted to place-based ways of working. These models align both vertical and horizontal structures while providing a degree of flexibility required to tailor collaboration at the local level to meet localised needs. The models or arrangements include:

- multilevel governance, which is a form of ongoing partnership dialogue and a strategy that enables different partners to work together (Miren 2019)

- network and collaborative governance which invests new degrees of power and influence in communities to enhance learning (feeding into policy design) through relationships and partnerships across public, private, community and third sectors (Wolfe 2018)

- distributed governance, which involves combining resources of governmental and non‑governmental actors in the forms of horizontal networks (Wolfe 2018).

- The Constellation Model, action-driven and ideal for groups that need to mobilize quickly around emergent issues and opportunities (Surman 2006).

- Coordinated Project, Campaign Coalition, and Ongoing Partnership models: developed by the Institute for Conservation Leadership. These models range from simple information networks to complex organizational structures (Byers 2011).

Shared accountability

For place-based approaches, accountability is based on locally‑driven outcomes tailored to local circumstances and shared between all stakeholders and government engaged in place-based work (Marsh 2017). Shared accountability, tied to outcomes, is necessary to ensure transparency and accountability in joined-up work. Shared accountability is guided by a clear shared vision driven by outcomes, jointly developed objectives, and trust between partners.

Case study: Community Revitalisation

A practice example for shared learning and accountability

Community Revitalisation (CR) is a community-led place-based initiative that operates in five communities in Victoria. The initiative brings together communities, their local leaders and government to design approaches to improve economic inclusion that are responsive to local needs and aspirations. Several learning activities have been used to support effective implementation of CR including:

- Quarterly Learning Forums with all CR sites to support collaborative design and decision‑making and drive effective CR delivery. DJPR staff co-develop the agenda and are active participants in the forums.

- Reflection points at different levels of frequency (weekly, fortnightly, monthly) to identify and respond to enablers, challenges and risk, and ground learnings to inform policy approaches.

- Interviews with stakeholders to surface initial learnings which informed the guiding model of CR, while also allowing for an iterative review of the model underpinning CR’s systemic focus.

- Collaborative design process alongside CR sites (including community members and other stakeholders) to inform theory of change and co-develop tailored impact and learnings plans for each site to track progress towards outcomes.

- Participation in peer-to-peer learning forums on a national scale – DJPR staff participated in online workshops and shared experiences about CR with the Federal Government’s Department of Social Services Place-Based branch, ensuring that valuable insights are shared across contexts on a national scale.

Role fluidity

Effective joining-up requires role fluidity, and not restricting to formal roles and responsibilities. ‘Role fluidity’ is the ability to move around multiple roles (e.g., diplomat, advocate, negotiator) to mobilise local actions, challenge systems and initiate change for enhanced collaboration across government and with local communities (McKenzie 2020).

Collective leadership and other key roles

Collaborative initiatives are often instigated and driven by the personal dedication and energies of a few individuals; and changes in leadership can affect momentum. Therefore, effective joined-up work requires a shift away from the dependence on the leadership of a few individuals to broader ‘collective ownership’ across multiple levels ranging from strategic, managerial, and local levels (Davison 2016).

Senior leadership has a role to play in supporting interagency collaboration and activity and setting the cultural tone and ethos for collaboration within their respective agencies. In the joined-up context, effective leaders will display ‘craftmanship,’ by using smart practices to step outside of formal structures or rules to facilitate joined-up working (Carey 2015). In this sense, strong leaders can break down existing patterns of working and entrenched practices.

Collective leadership has a critical role in nurturing the right skills and attitudes amongst staff and in finding workarounds for structural issues. They play a central role in developing, promoting, and strengthening a joined-up culture, values, and ethos.

Leadership is also needed establish a shared vision and strengthen horizontal linkages between agencies. Leaders as ‘purposive practitioners’ who can leverage opportunities for inter-agency collaboration, engage in joint problem‑solving and overcome obstacles to success (O'Flynn 2011).

The role of boundary spanning

Boundary spanning is a key means by which VPS staff and leadership can engage in joined‑up ways of working across government and with communities. Staff who act as boundary spanners traverse and build bridges across organisational, cultural, jurisdictional boundaries for the realisation of shared goals. Boundary spanning roles are described in various terms including networker, collaborator, conduit, ambassador, civic entrepreneur depending on the institutional context, the quality of relationships and their individual characteristics and skills (Williams 2002). Key functions of boundary spanning include (Barner-Rasmussen 2010):

- Linking

- connecting/linking different people and processes across organisational boundaries

- building sustainable and effective relationships and networks, including through:

- information sharing and exchange

- translating across boundaries (bringing together two world domains, speaking different languages and functioning according to different principles, routines, and procedures)

- marshalling expertise across portfolios and building social capital.

- Facilitating

- creating and establishing new or innovative cooperative arrangements between local community, local government and/or professional organisations

- Intervening (actively intervene to create positive outcomes)

- solution brokering

- negotiators.

VPS capabilities

The culture and capability of the VPS is critical for successful joined-up efforts.

In the context of capability building, factors that promote a joined-up culture of working are:

- investment in a learning culture that facilitates collegiate behaviour and opportunities for cross-fertilisation, information-sharing and the development of strong networks across the VPS

- commitment of time for VPS capacity building

- commitment to sufficient budget, time, and resources to develop, manage and support engagement and collaboration processes and practices with community and other stakeholders

- skills, training, and leadership support for the VPS to authorise and engage in joined‑up work

- development of appropriate tools and resources to facilitate stakeholder collaboration and engagement in place-based initiatives.

Skills, training, and support required for effective joined-up work

Joined-up approaches require skillsets and capabilities, and as noted above, these need to be complemented by supportive systems and processes as well as an enabling culture that promotes better collaboration across government and communities. Inadequate training for staff can weaken efforts to facilitate joined-up ways of working (O'Flynn 2011).

The following key skills and capabilities have been identified as fundamental to effective joined-up work (Shergold 2004; State Services Authority 2007; Halligan, Buick & O’Flynn 2011; Carey & Crammond 2015).

Key capabilities:

- capacity to balance the tension between short-term and long-term goals

- readiness to think and act across agency boundaries

- knowledge of both how to work with community and how to obtain information about community (demographics, needs and so on)

- the capacity to build strategic alliances, collaboration, and trust

- flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances

- capacity among public sector staff to engage in cross-sector, co-creation efforts.

Skills:

- willingness to undertake emotional labour associated with relational working

- relational skills to foster trust, reciprocity, empathy and mutual accountability towards commitments and shared outcomes

- coordination

- effective knowledge management

- creative conflict resolution

- inter-agency project management

- cultural and solution brokering (seeing what needs to happen)

- community engagement

- technological know-how (e.g., data sharing platforms).

Tools and resources for the VPS that enable better joined‑up ways of working in place

As illustrated in this report, effective joined-up work is enabled through supportive organisational systems and processes coupled with appropriate skills, mindsets and cultures.

While joined-up work is fundamental to place-based approaches, it is also highly relevant to how government can effectively address complex and cross-cutting policy challenges and build a more responsive public service.

The Place-based Agenda has developed a suite of resources and tools to support VPS to enable better place-based and joined-up ways of working, including:

- The Place-Based Guide: provides advice on working with communities to design and implement place‑based approaches including collaborative ways of working

- The Funding Toolkit: in-depth guidance on agile and adaptive funding

- The Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL) Toolkit: in-depth guidance on designing and implementing MEL in place-based contexts with communities

- The Place-based Capability Framework: developed in partnership with the Victorian Public Service Commission defines and describes clear, concise, observable, and measurable capabilities that are needed when working with place-based approaches. It can be used throughout the employee lifecycle, from recruitment and selection to performance, team, and career development.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Joining-up across government and communities is a dynamic process which requires versatile systems, structures and processes that can shift over time with changing priorities, situations, and stakeholders.

There is no one-size-fits all approach to joined-up work. It is a long-term endeavour that requires time, patience, and willingness to implement. Accountability and risk management are central concerns, as are a careful balancing of vertical and horizontal accountabilities.

Joined-up ways of working break down government silos and enable cooperation through the sharing of resources and rewards across departments. They can improve communication and information sharing between departments and community stakeholders and increase flexibility needed to address cross‑cutting issues. For place-based ways of working, joined-up work encourages innovation, deepens public trust in government, and enables the VPS to be an effective partner to place-based initiatives.

Joined-up work requires effective changes in accountability systems, VPS culture and ethos and structural arrangements; all of which influence how the VPS engages with community and other stakeholders. Effective collaboration (for generating change and community impact) should be built on a sound foundation; and this involves identifying a shared agenda, determining how to effectively work together, and developing a strategy to move from idea to impact.

A series of proposals have been developed as a ‘call to action’ for the VPS designed to address ongoing challenges and capitalise on opportunities, based on research and consultations with key stakeholders.

The effectiveness of joined-up work is dependent on strong leadership commitment, investment in time and resources, individual and organisational flexibility, and openness to creativity and innovation.

A ‘Call to Action’ for the VPS

- Dedicated leadership to provide an authorising and enabling environment for joined-up work across the VPS by:

- securing cross-government commitment to joined-up ways of working in line with public sector values and First Nations’ principles for self-determination

- developing strong ‘inter-organisational’ executive leadership to:

- champion and advocate for place-based efforts

- build links and networks across VPS

- set goals for collaboration

- facilitate consensus and broker resources to achieve collective goals

- building strong inter-organisational executive capability to lead joined-up and place‑based ways of working.

- When working ‘in place’ alongside other departments or agencies, work collaboratively to:

- identify opportunities to determine shared approaches, objectives, and outcomes

- share accountability through collaborative governance structures

- develop joint models or approaches for funding and reporting that support joined-up practices and arrangements (for example, pooled budgets for cross‑cutting issues).

- Invest in systems that enable joined-up work by:

- dedicating resourcing and supportive infrastructure to facilitate better coordination, communication and information sharing across VPS. For instance, improved platforms and processes for locating key contacts or accessing relevant information across government or provide VPS staff with a digital shared space to collaborate

- developing and agreeing a coordinated approach to streamline the work of departments engaged in place-based work.

- Enhancing appropriate VPS skills and capabilities by:

- dedicating resourcing for skills training in collaborative approaches

- creating dedicated ‘boundary spanning’ roles at the appropriate VPS levels

- developing inbound-outbound staff exchange programs to share expertise, foster greater respect and trust and shared perspectives between the public, private and third sectors

- providing ongoing localised cultural awareness training for cross- portfolio staff

- creating incentives for VPS staff to work more collaboratively by:

- embedding collaborative work as a key performance indicator and essential criteria in position descriptions, and

- setting goals and expectations for collaborative work with other departments and shared outcome targets in staff performance development plans.

References

Alderton, A, Villanueva, K, Davern, M., Reddel, T, Lata, L.N., Moloney, S, Gooder, H, Hewitt, T, DeSilva, A, Coffey, B, McShane, I, Bayram, M, 2022, What works for place-based approaches in Victoria. Part 1: A review of the literature. Report prepared for the Victorian Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions.

ANZSOG (Australian and New Zealand School of Government), Becoming a boundary spanning public servant, October 2020.

Australian Social Inclusion Board, 2011, Governance Models for Location Based Initiatives, Australian Social Inclusion Board Secretariat, DPC, Canberra, p. 30.

Barner-Rasmussen, W, Ehrnrooth, M, Koveshnikov, A, Mäkelä, K 2010: Functions, resources and types of boundary spanners within the MNC, Proceedings, pp. 1–6.

Buick, F, 2012. Panacea for joined-up working: the rhetoric and reality gap, doctorate thesis, University of Canberra.

Byers, R 2011, Models and elements of collaborative governance, Ontario Public Health Association, Ontario.

Carey, G & Crammond, B. 2015, What works in joined-up government? An evidence synthesis, International Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 00, No. 1-10.

Christensen, T & Lægreid, P, 2007, The whole-of-government approach to public sector reform. Public Administration Review, No. 67, Vol. 6, pp.1059–1066.

Davison, N, 2016, Whole-of-government reforms in New Zealand: The case of the Policy Project, Institute of Government, London.

Ferguson, D, Phil, M. & Burlone, N 2009, Understanding Horizontal Governance, Research brief.

Halligan, J Buick, F & O’Flynn, J 2011, Experiments with joined- up, horizontal and whole- of- government in Anglophone countries, In A Massey (Ed.), International Handbook on Civil Service Systems (1 ed., pp. 77-99). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Marsh, I Crowley, K Grube, D & Eccleston, 2017, R Delivering public services: locality, learning and reciprocity in place based practice, Australian Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 76, No. 2, pp. 443-456.

McKenzie, F & Cabaj, M 2020, Changing Systems, Power & Potential, A synthesis of insights from the Canberra Workshop 2-3 March 2020, Collaboration for Impact.

Miren, L Miren, E Martina, P. 2019, Multilevel governance for Smart Specialisation: basic pillars for its construction, EUR 29736 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Emerson, K, Nabatchi, T & Balogh, S. 2012, An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Vol: 22, No: 1, pp. 1–29.

O'Flynn, J, Buick, F Blackman, D & Halligan, J 2011, You Win Some, You Lose Some: Experiments with Joined-Up Government, International Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 34: No. 4, pp. 244 — 254.

Shergold, P, 2004, Connecting government: Whole of government responses to Australia’s priority challenges, Management Advisory Committee, Canberra.

State Government of Victoria State Services Authority, 2007, Victorian approaches to joined-up government, an overview, State Services Authorly, Melbourne.

Surman, T 2006, Constellation Collaboration: A model for multi-organizational partnership, Centre for Social Innovation, Toronto.

Szirom, T, 2014. Thinking through Joint Action Workbook, Brotherhood of St Laurence.

UK National Audit Office, 2001, Joining Up to Improve Public Services, London: Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General, House of Commons, Session 2001–2002.

Weaver, L, 2021, Solving the puzzle of collaborative governance, Tamarack Institute, Ontario.

Williams, P 2002, The Competent Boundary Spanner. Public Administration, vol. 80, pp. 103-124.

Wolfe, D 2018, Experimental Governance: Conceptual approaches and practical cases, Background paper for an OECD/EC Workshop on 14 December 2018 within the workshop series “Broadening innovation policy: New insights for regions and cities”, Paris.