- Date:

- 5 July 2021

Introduction

The Victorian Independent Remuneration Tribunal (Tribunal) was established in 2019 by the Victorian Independent Remuneration Tribunal and Improving Parliamentary Standards Act 2019 (VIRTIPS Act) to support transparent, accountable, and evidence-based decision-making in relation to the remuneration of elected officials and public sector executives in Victoria.

To date, the Tribunal has made Determinations setting the value of:

- salaries and allowances for Members of the Parliament of Victoria

- remuneration bands for executives employed in public service bodies

- remuneration bands for executives employed in prescribed public entities.

On 6 April 2020, the VIRTIPS Act was amended to require the Tribunal to make a Determination setting the value of the amount of the allowance payable to Mayors, Deputy Mayors and Councillors (Council members) and providing for Council allowance categories.1

Council members are elected every four years to represent their municipal community.

The Local Government Act 2020 (Vic) entitles Council members to receive an allowance in accordance with a Determination of the Tribunal.2

On 17 June 2021, the Minister for Local Government, in consultation with the Minister for Government Services, formally requested the Tribunal to make the Determination for Council members. This request was made under section 23A(4) of the VIRTIPS Act.

In July 2021, along with this consultation paper, the Tribunal published on its website a notice of intention to make the first Determination of allowances for Mayors, Deputy Mayors and Councillors.

The VIRTIPS Act provides that the Tribunal’s first Determination on local government takes effect on the day after the expiry of the period of six months after the Tribunal receives the request from the Minister for Local Government’.3 Therefore, the first Determination will take effect on 18 December 2021.

This consultation paper:

- sets out the matters the Tribunal proposes to consider in making the Determination

- invites interested persons or bodies to make a submission to the Tribunal on these or other relevant matters

- includes specific questions the Tribunal would particularly like to see addressed in submissions.

References

- VIRTIPS Act, s23A(1) and (2).

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), s39.

- VIRTIPS Act, s23A(4).

Call for submissions

The Tribunal invites interested persons or bodies to make a written or oral submission in relation to the Determination.

Submissions (and requests for assistance with making a submission) may be made at localgovernment@remunerationtribunal.vic.gov.au.

Written submissions must be received by the Tribunal by 5pm on Monday 16 August 2021.

Those wishing to make an oral submission must advise the Tribunal by 5pm on Monday 26 July 2021.

All submissions will be published (in full or in summary) on the Tribunal website unless the person or body making the submission seeks confidentiality. If a submission contains commercially-sensitive information, it will be published in a form which protects commercial sensitivity.

Submissions that contain offensive or defamatory comments, or which are outside the scope of the Determination, will not be published.

The Tribunal may receive a request under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (Vic). Any such requests will be determined in accordance with that Act which has provisions designed to protect personal information and information given in confidence. Further information can be found at the Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner.

In addition to inviting submissions, the Tribunal will directly invite current Council members to complete an online questionnaire.

Consultation questions

Without limiting the matters persons or bodies may wish to raise in a submission, the Tribunal is particularly interested in receiving submissions on the following questions.

Roles of Council members

- What are the most important duties and responsibilities of Mayors, Deputy Mayors and Councillors?

- How have the roles and responsibilities of Council members changed since the last review of Councillor allowances in 2008? What future challenges may emerge?

- How are Council member roles affected by a Council’s electoral structure (for example, ward structure or ratio of Council members to population)?

Purpose of allowances

- What is, or should be, the purpose of allowances for Council members?

Allowance category factors

- What factors should be considered when allocating Councils to allowance categories? Is the existing system, in which Councils are allocated to categories based on population and revenue, appropriate?

Adequacy of allowances

Are current allowance values adequate, for example to:

- attract suitable candidates to stand for Council?

- reflect the costs (e.g. time commitment) and benefits of Council service?

- support diversity amongst Council members and potential candidates?

Superannuation

- How, if at all, should superannuation be considered in determining allowance values?

Comparators

- The Tribunal is required to consider allowances for persons elected to ‘voluntary part‑time community bodies’ when making the Determination. Which bodies should the Tribunal consider, and why?

- The Tribunal is also required to consider similar allowances for elected members of local government bodies in other States. Which States are particularly relevant (or not) for this purpose, and why?

Financial impacts

- What are the financial impacts of varying allowance values for Council members?

Scope of the Determination

Section 23A(1) of the VIRTIPS Act states that the Tribunal must make a Determination setting the value of the amount of the allowance payable to Council members. There are Council members in 79 Councils in Victoria.

The Determination must provide for Council allowance categories (which may be specified for a single Council, or for a group of Councils).4 When making the first Determination in relation to Council members, the Tribunal must:5

- include a comprehensive review of the existing allowance categories and Councillor and Mayoral allowances under the Local Government Act 1989 (Vic), taking into account similar allowances for elected members of local government bodies in other States and allowances for persons elected to other ‘voluntary part-time community bodies’

- provide for the annual indexation of allowances

- set the value of allowances at not less than the existing equivalent allowances under the Local Government Act 1989 (Vic)

- provide for any other relevant matter that the Tribunal considers relevant.

Until the Tribunal’s first Determination is made and comes into effect, the allowances set under the Local Government Act 1989 (Vic), City of Melbourne Act 2001 (Vic) and City of Greater Geelong Act 1993 (Vic) continue in effect.

The Determination will not apply to the following:

- administrators and Municipal Monitors appointed to a Council — remuneration for these roles is fixed by the Minister for Local Government6

- Council staff, including the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of each Council.7

The Determination will also not apply to Council expenses policies, which relate to the reimbursement of out-of-pocket expenses for Council members, or to the resources and facilities provided by Councils to Council members to perform their role.8

The Determination will not apply to a member of a delegated committee9, unless the member is also a Council member.

References

- VIRTIPS Act, ss23A(2) and (3).

- VIRTIPS Act, s23A(5).

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), ss179 and 220.

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), s45.

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), ss41 and 42.

- Under s11 of the Local Government Act 2020, a Council may delegate certain powers, duties or functions to a delegated committee. A delegated committee must include at least two Councillors and ‘may include any other persons appointed to the delegated committee by the Council who are entitled to vote’ (s63 of the Local Government Act 2020 (Vic)).

The Tribunal's proposed approach

In making a Determination, the Tribunal must also consider:

- any statement or policy issued by the Government of Victoria which is in force with respect to its wages policy (or equivalent) and the remuneration and allowances of any specified occupational group

- the financial position and fiscal strategy of the State of Victoria

- current and projected economic conditions and trends

- submissions received in relation to the proposed Determination

- any other prescribed matter.10

As earlier indicated, without limiting the matters on which persons or bodies might wish to make a submission, the Tribunal is particularly interested in receiving submissions on:

- the role of Council members

- the purpose of allowances for Council members

- the factors for consideration in allocating Councils to allowance categories

- the adequacy of the current allowance values

- how superannuation should be taken into account in determining allowance values, if at all

- the relevant ‘voluntary part-time community bodies’ and local government bodies for allowance comparison purposes

- the financial impacts of varying allowance values.

To help facilitate submissions, some of these matters are discussed in the following chapters.

References

- VIRTIPS Act, s24(2).

Overview of roles of Councils and Council members

In Victoria, local government is a distinct tier of government consisting of democratically-elected Councils.11 Each Council represents a municipal district, and each must consist of between five and 12 Council members who are elected by residents of the district and ratepayers.12

The role of each Council is to provide good governance for the benefit and wellbeing of the municipal community,13 which includes residents, ratepayers, traditional landowners and people and bodies who conduct activities in the municipal district.14

Councils receive funds by levying municipal rates. Councils also receive grant funding from federal and state governments. Councils have wide-ranging responsibilities under more than 120 pieces of Victorian legislation, including land use planning and building control, public health services, domestic animal control and environmental protection legislation.15

Councils are also responsible for maintaining community infrastructure (e.g. town halls, libraries, parks and gardens) and may make and enforce local laws, provided they do not contradict existing state or federal laws.16

In November 2020, a Ministerial Statement on Local Government set out the Victorian Government’s priorities for the local government sector, including:

- setting out the role of Councils in supporting Victoria’s pathway through social and economic recovery from the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic

- implementing a fairer rating system for those experiencing hardship

- supporting local businesses

- starting a conversation on cultural change

- building on the Local Government Act 2020 (Vic) reforms to continue to strengthen the sector.

Municipal districts in Victoria vary significantly in terms of population, total recurrent revenue17 and geographical size. For example, the smallest municipal district is just under 9 km2 (Borough of Queenscliffe) and the largest is over 22,000 km2 (Rural City of Mildura).18 The Borough of Queenscliffe also has the smallest population (approximately 3,000 people) while the largest population – over 350,000 people – is found in the City of Casey.19 In 2019-20, the Borough of Queenscliffe had total recurrent revenue of around $12 million, while the City of Melbourne had over $760 million – a more than 60-fold difference.20

To undertake a comparative analysis of Council performance, Local Government Victoria (LGV)[11] divides Councils into five categories – Metropolitan, Interface, Regional City, Large Shire and Small Shire. The Councils included in each category vary widely in terms of population, geographical size and recurrent revenue (table 1).

Table 1: Population, area and total recurrent revenue by LGV Council category

| Category | Resident population (estimated) |

Area (km2) |

Total recurrent revenue ($ million) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metropolitan |

maximum average minimum |

209,568 147,381 93,482 |

130 66 20 |

761 214 139 |

| Interface |

maximum average minimum |

353,962 195,302 65,099 |

2.468 820 409 |

519 296 99 |

| Regional City |

maximum average minimum |

258,938 81,073 19,920 |

22,082 3,938 121 |

399 159 53 |

| Large Shire |

maximum average minimum |

53,394 31,478 16,017 |

20,940 4,912 866 |

106 71 39 |

| Small Shire |

maximum average minimum |

16,699 9,846 2,939 |

9,108 4,509 9 |

40 30 12 |

Sources: ABS, Estimated Resident Population by Local Government Area, June 2019; ABS, Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): Volume 3 – Non ABS Structures, cat. no. 1270.0.55.003, June 2020; Victorian Local Government Grants Commission data collection for the 2019-20 financial year, https://www.localgovernment.vic.gov.au/council-funding-and-grants/victo….

Role and responsibilities of Mayors

The Mayor serves as the Council’s leader and principal spokesperson.22 Apart from Melbourne City Council and Greater Geelong City Council, Council members are required to elect a Council member to the role of Mayor by absolute majority for a term of one or two years.23

For Melbourne City Council, the Lord Mayor is directly elected by residents and ratepayers for a four-year term.24 For Greater Geelong City Council, the Mayor is elected for a two-year term.25

Key aspects of a Mayor’s role

- chair Council meetings

- lead regular reviews of the performance of the CEO

- promote behaviour among Councillors that meets the standards of conduct set out in the Councillor Code of Conduct

- assist Councillors to understand their role

- provide advice to the CEO when the CEO is setting the agenda for Council meetings

- perform civic duties on behalf of the Council

- report to the municipal community, at least once each year, on the implementation of the Council Plan

- lead engagement with the municipal community on the development of the Council Plan

- be principal spokesperson for the Council.

The Mayor is responsible for leading regular reviews of the performance of the CEO, who is the only staff member appointed by the Council. The role of the CEO is to oversee the day-to-day management of the Council's operations, provide advice to Council and ensure that Council decisions are implemented. The CEO is also responsible for supporting the Mayor and the development, implementation and enforcement of policies to manage interactions between Council members and Council staff.

Mayors also have the power to:

- appoint a Councillor to be the chair of a delegated committee

- direct a Councillor, subject to any procedures or limitations specified in the Governance Rules, to leave a Council meeting if the Councillor’s behaviour is preventing the Council from conducting its business

- require the CEO to report to the Council on the implementation of a Council decision.26

Role and responsibilities of Deputy Mayors

Prior to November 2020, the office of Deputy Mayor was only recognised in legislation for Melbourne City Council and Greater Geelong City Council.27

Since that time, all Councils may establish an office of Deputy Mayor.28 As at November 2020, 69 of the 79 Councils had elected Deputy Mayors.29

For Councils other than Melbourne City Council, if a Council chooses to establish an office of Deputy Mayor, the Deputy Mayor must be elected by an absolute majority of Councillors at a meeting that is open to the public.30 Deputy Mayors are appointed for a term of one or two years, after which a new election must be held.31

In comparison, the Deputy Lord Mayor of Melbourne City Council is directly elected by residents and ratepayers for a four-year term.32

Where a Council has established an office of Deputy Mayor, Deputy Mayors must perform the role of the Mayor, and may exercise the Mayoral powers, in any of the following circumstances:

- when the Mayor is unable for any reason to attend a Council meeting, or part of a Council meeting

- when the Mayor is incapable of performing the duties of the office of Mayor for any reason, including illness

- when the office of Mayor is vacant.33

Role and responsibilities of Councillors

The key aspects of a Councillor’s role include participating in the decision-making of Council, representing the interests of the municipality and participating in strategic planning activities.

Key aspects of a Councillor's role:

- liaise with other levels of government, the private sector and non-government community groups

- participate in the decision-making of the Council

- take part in Council committees

- represent the interests of the municipal community when making decisions

- contribute to the strategic direction of the Council through development and review of key strategic documents, including the Council Plan

- together with other Councillors, determine the Council's financial strategy and budget and allocate resources

- attend Council meetings and relevant community events

- together with other Councillors, appoint a CEO and manage and review their performance.

Councils also play a key role in setting and administering planning schemes and providing permits in accordance with those schemes for the municipal area. According to the Good Governance Guide for local government decision-makers:

Another challenging aspect of a councillor’s role can occur when council is the Responsible Authority under the Planning and Environment Act 1987. In this instance council, and therefore councillors, are in quasi-judicial role making planning permit decisions based on the interpretation of the relevant legislation.34

Time commitment of Council role

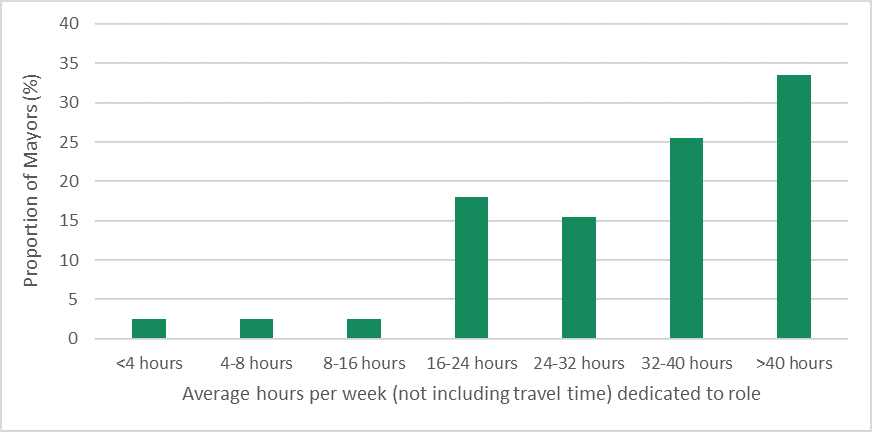

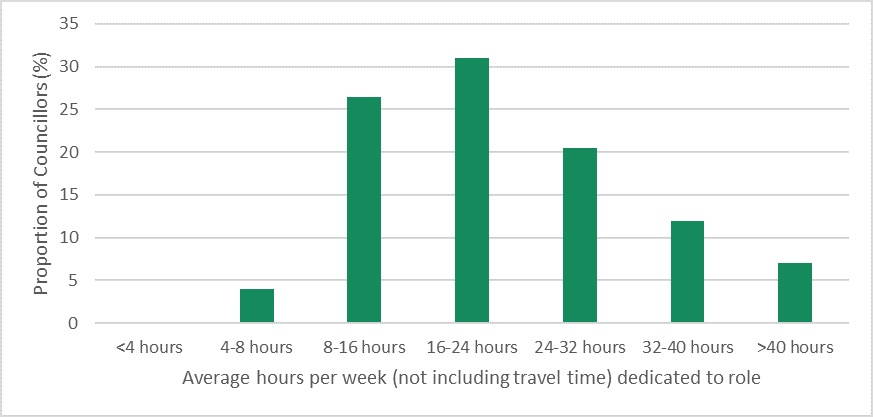

The role of Mayor has been described as a full-time commitment.35 For example, in a 2019 survey conducted by the Local Government Inspectorate (LGI),36 around one-third of respondents who were Mayors reported spending more than 40 hours per week on the role, and approximately one-quarter reported spending between 32 and 40 hours per week.

Other impacts of Council role

Many Council members participate in paid employment outside their role on Council,44 and some may find it challenging to manage the demands of both roles.45 In addition, a Council member’s duties may affect their ability to undertake caring or other responsibilities.

The MAV Councillor census conducted in 2017 reported that around half of all female respondents had caring responsibilities for children and/or dependents, compared to less than 30 per cent of male respondents.46 The 2019 LGI survey reported that over 80 per cent of respondents who were Mayors, and around 75 per cent who were Councillors, indicated that balancing work, family and their role on Council was the most challenging or difficult part of the role.47

On the other hand, there may be benefits to serving on Council. A 2013 survey of newly-elected Council members, conducted by the Victorian Local Governance Association (VLGA),48 found that respondents generally viewed their overall experience as positive with benefits such as:

- exposure to new learning experiences

- the opportunity to make a difference in the local community and the satisfaction of participating and bringing their voice to Council

- a sense of privilege and honour from representing and working with the community.49

Serving on a Council may also provide relevant experience for Council members who intend to stand for state or federal parliament. For example, as at May 2021, almost 20 per cent of the sitting Members of the Parliament of Victoria had previously served as a Council member.50

Trends affecting the roles of Council members

Some recent trends that may have affected the roles of Council members include:

- changes in the role of Councils

- governance changes for Councils

- population changes within Council areas

- increased use of social media.

Changes in the role of Councils

The Ministerial Statement on Local Government noted that the COVID-19 pandemic:

… has seen a change in the way many Victorians interact with the local services, businesses and recreation opportunities closer to home.51

The Ministerial Statement also drew attention to the role of Councils in supporting social and economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, including through investing in community infrastructure and supporting local businesses.52

Governance changes

Amendments to local government legislation made in 2020 require Councils to undertake longer-term planning. For example, Councils must develop, adopt and keep in force both a financial plan and an asset plan addressing at least the next ten financial years.53

Population changes

Between 2009 and 2019, Victoria’s population increased by around 23 per cent while the number of Councils remained unchanged.

Population growth has been unevenly distributed across municipal districts. For example, while the population of the City of Melbourne grew by around 90 per cent between 2009 and 2019, the Shire of West Wimmera experienced a decline of around 13 per cent over the same period. A 2018 Parliament of Victoria inquiry noted that Councils with an increasing population are required to manage their community’s growing need for infrastructure and services, while small Councils with a declining population face the challenge of maintaining services and assets with a decreasing revenue base.54

Use of social media

Social media is increasingly used as a tool to communicate with members of the community and to campaign at elections, particularly in metropolitan areas.55 While social media can make it easier for Council members to reach their constituents, it may also expose them to online harassment and attacks, including by anonymous parties.56

References

- Constitution Act 1975 (Vic), s74A.

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), ss12 and 13.

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), s8(1).

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), s3.

- Local Government Victoria, ‘Guide to Councils – How Councils Work: Acts and Regulations’, Know Your Council, accessed 2 March 2021, https://knowyourcouncil.vic.gov.au/guide-to-councils/how-councils-work/….

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), s71.

- Section 73A(5) of the Local Government Act 1989 (Vic) defines total recurrent revenue as ‘the total revenue of the Council reported in the financial statements of the Council for the previous financial year after adjusting for any items that are extraordinary, abnormal or non-recurring’. This includes rates, charges and some grants, but excludes one-off payments.

- ABS, Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): Volume 3 – Non ABS Structures, cat. no. 1270.0.55.003, June 2020.

- ABS, Estimated Resident Population by Local Government Area, June 2019.

- Victorian Local Government Grants Commission data collection for the 2019-20 financial year, https://www.localgovernment.vic.gov.au/council-funding-and-grants/victo….

- LGV is a part of the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions. LGV provides policy advice and works with local Councils to support delivery of local government services. Local Government Victoria, ‘What we do’, Local Government Victoria, accessed 21 April 2021, https://www.localgovernment.vic.gov.au/.

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), s18.

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), ss25 and 26.

- City of Melbourne Act 2001 (Vic), ss12 and 14.

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), s26(2).

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), s19.

- City of Melbourne Act 2001 (Vic), s6; City of Greater Geelong Act 1993 (Vic), s11C.

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), s20A.

- Tribunal analysis based on Local Government Victoria, ‘Find a Council’, Know Your Council, accessed 21 April 2021, https://knowyourcouncil.vic.gov.au/councils.

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), s27.

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), s27.

- City of Melbourne Act 2001 (Vic), ss12 and 14.

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), s21.

- VLGA, MAV, LGV and Local Government Professionals, Good Governance Guide (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, 2012), 22.

- Local Government (Councillor Remuneration Review) Panel, Local Government (Councillor Remuneration Review) Panel Report (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, January 2008), 15.

- LGI is an independent agency tasked with ensuring that Councils follow the Local Government Act 2020 (Vic). LGI, ‘About the Local Government Inspectorate’, accessed 29 June 2021, https://www.lgi.vic.gov.au/about-local-government-inspectorate.

- LGI, Councillor expenses and allowances: equitable treatment and enhanced integrity (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, September 2020).

- MAV is a body corporate established under the Municipal Association Act 1907 (Vic) to support and promote local government in Victoria. Each Council in Victoria may appoint a Council member as its MAV representative, and the appointed representatives together constitute the MAV.

- MAV, ‘Councillor expectations and support’, Vic Councils, accessed 21 April 2021, https://www.viccouncils.asn.au/stand-for-council/being-a-councillor/cou….

- LGI, Councillor expenses and allowances: equitable treatment and enhanced integrity (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, September 2020), 13.

- Local Government Electoral Review Panel, Local Government Electoral Review Stage 2 Report (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, July 2014), 4; Victorian Electoral Commission, Local Council Representation and Subdivision Reviews 2019‑20 Program Report (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, 2020), 6.

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), s4.

- Victoria, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 14 November 2019, 4322 (Marlene Kairouz, Minister for Consumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation, Minister for Suburban Development, second reading speech for the Local Government Bill 2019).

- The MAV Councillor Census conducted in 2017 found that around two-thirds of respondents were either working in paid employment or self-employed in addition to their role on Council. MAV, MAV Councillor Census (Municipal Association of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, 2018), 13.

- VLGA, Journey from Citizen to Councillor: A report on newly elected Councillors in Victoria (Victorian Local Governance Association: Carlton, 2014), 13.

- MAV, MAV Councillor Census (Municipal Association of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, 2018), 3.

- LGI, Councillor expenses and allowances: equitable treatment and enhanced integrity (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, September 2020).

- The VLGA is an independent organisation that supports Councils and Councillors, including through opportunities for networking, professional development and information exchange. VLGA, ‘About’, accessed 16 June 2021, https://www.vlga.org.au/about-vlga.

- VLGA, The Journey from Citizen to Councillor, a report on new newly elected councillors in Victoria (Victorian Local Governance Association: Melbourne, Victoria, July 2014), 21.\

- Data provided to the Tribunal by the Parliamentary Library, Parliament of Victoria

- The Hon Shaun Leane MP, Ministerial Statement on Local Government, 2020, 1.

- The Hon Shaun Leane MP, Ministerial Statement on Local Government, 2020, 3-4.

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), ss91 and 92.

- Parliament of Victoria, Final report of the inquiry into the sustainability and operational challenges of Victoria’s rural and regional councils (Victorian Government Printer: Melbourne, Victoria, March 2018), 24-26.

- Wayne Williamson and Kristian Ruming, ‘Social Media Adoption and Use by Australian Capital City Local Governments’, in Mehmet Zahid Sobaci (ed), Social Media and Local Governments (Springer International Publishing: Switzerland, 2016): 113‑130.

- VLGA, Submission to the Inquiry into the Impact of Social Media on Elections and Electoral Administration, 4 November 2020; More Women for Local Government Facebook Group, Submission to the Inquiry into the Impact of Social Media on Elections and Electoral Administration, 30 October 2020.

Existing Council allowances system

The existing Council allowances system consists of:

- Council allowance categories, which group Councils according to recurrent revenue and estimated resident population

- allowance limits and ranges that apply to Council members according to their Council category

- a payment in lieu of superannuation entitlements — eligibility requirements apply

- a Remote Area Travel Allowance — eligibility requirements apply.

The existing system largely reflects the outcomes of reviews undertaken by government-appointed panels in 2000 (2000 Allowances Review)57 and 2008 (2008 Allowances Review).58

Purpose of allowances

The purpose of Council member allowances is not set out in legislation.

In making the Determination, the Tribunal is required to consider any statement or policy issued by the Government of Victoria with respect to the remuneration and allowances of Mayors, Deputy Mayors and Councillors.59

In 2008, the Victorian Government released Recognition and Support, the Victorian Government’s Policy Statement on Local Government Mayoral and Councillor Allowances and Resources (2008 Policy Statement).60

The letter from the Minister for Local Government to the Tribunal, dated 17 June 2021, cited the 2008 Policy Statement and stated that:

While this policy notes that the Government views councillor allowances not as a form of salary, but as recognition of the contributions made by those elected to voluntary, part-time roles in the community, the Tribunal may wish to consider whether this view supports a contemporary local government sector that attracts diverse community perspectives to civic life.

The 2019 LGI survey revealed differences in how Mayors and Councillors viewed the purpose of their allowance:

- the most common response from Mayors was that their allowance is a form of salary or wages (37 per cent)

- the most common response from Councillors was that their allowance covered costs relating to the role (35 per cent)

- around one-quarter of both Mayor and Councillor respondents characterised their allowance as representing recognition of their contributions as elected representatives.61

Existing Council allowance categories

With the exception of Melbourne City Council, Councils are currently assigned to one of three allowance categories via a ‘Category Points’ system, which takes into account each Council’s total recurrent revenue and estimated resident population.62

Council allowance categories were first introduced in Victoria in 2001.63 This followed the 2000 Allowances Review which found that, in the absence of more robust measures of the complexity of a Council member’s role:

- population size was a reasonable indicator of the representational workload involved

- total revenue was an indicator of the size and complexity of the governance role.64

The 2000 Allowances Review led to the establishment of a three-category allowance framework. Each category corresponds to a range of allowance values that may be paid to Council members. Each Council may select an actual allowance value taking into account factors such as:

- whether the Council has a greater regional focus than others in the same allowance category

- socio-economic or demographic differences that result in ‘higher than usual’ demands on Council services, relative to other Councils in the same allowance category

- expectations placed on the Mayor by the community.65

Council allowance categories and Category points ranges

- Category 1 - 0-40

- Category 2 - 41-190

- Category 3 - 191+

Source: State Government of Victoria, Recognition and Support, the Victorian Government’s Policy Statement on Local Government Mayoral and Councillor Allowances and Resources, 2008.

Calculating a Council’s Category Points

Category Points=(R×D+P) / 1,000

Where:

- R is the Council’s total recurrent revenue (in $’000s) for the most recent financial year as submitted by the Council to the Victorian Local Government Grants Commission.

- D is an index for discounting total recurrent revenue (used to avoid increases in Category Points resulting from revenues increasing with inflation) which is calculated annually using Average Weekly Earnings data published by the ABS.

- P is the estimated resident population of the Council based on the latest data published by the ABS as at 30 June in the most recently completed financial year.

Source: State Government of Victoria, Recognition and Support, the Victorian Government’s Policy Statement on Local Government Mayoral and Councillor Allowances and Resources, 2008.

A Council, not otherwise eligible according to its Category Points result, may be assigned a higher allowance category in exceptional circumstances (e.g. by making a successful submission to a Local Government Panel).66

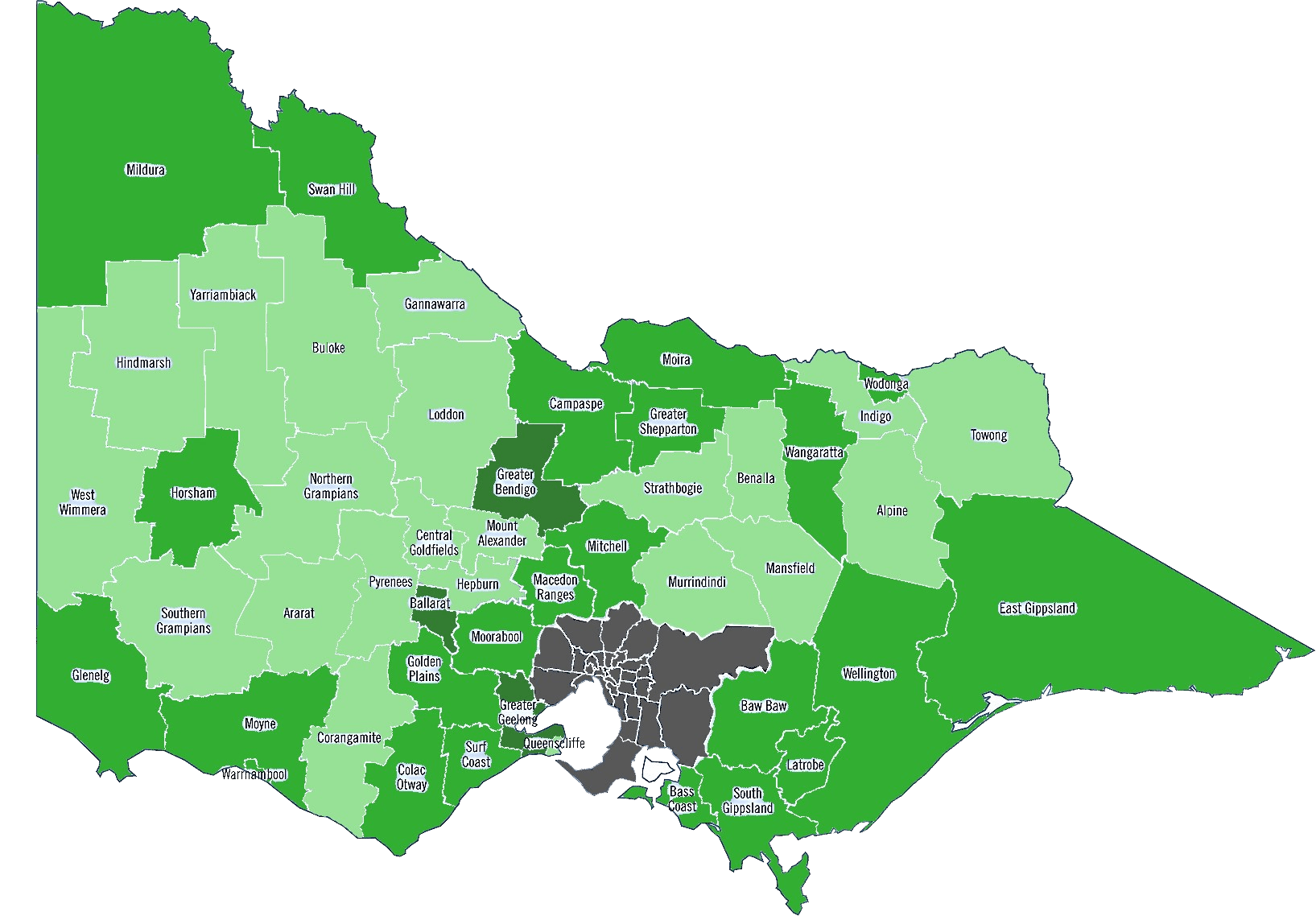

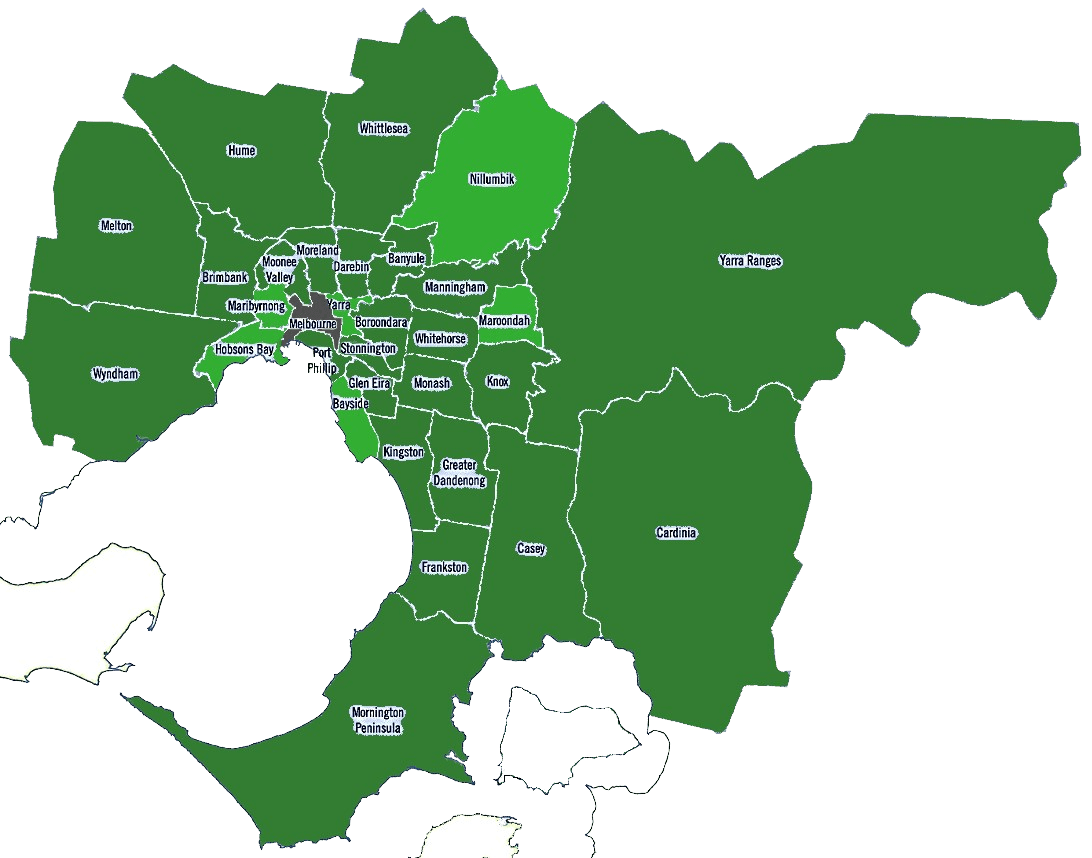

Figure 5 shows the location of Councils in Victoria and the allowance categories that apply to them. Appendix A also lists Councils by their allowance category as at June 2021.

Of the 31 Councils in LGV’s ‘Metropolitan’ and ‘Interface’ Council categories:

- around 75 per cent (24 Councils) are in allowance Category 3

- around 20 per cent (six Councils) are in allowance Category 2

- none are in allowance Category 1

- one Council (Melbourne City Council) does not belong to any allowance category.

In comparison, of the 48 Councils in LGV’s ‘Regional City’, ‘Large Shire’ and ‘Small Shire’ Council categories:

- just over half (25 Councils) are in allowance Category 2

- around 40 per cent (20 Councils) are in allowance Category 1

- around 6 per cent (three Councils) are in allowance Category 3.

Existing Council member allowance values

Table 3 sets out existing allowance ranges that apply to Council members according to their Council category.[1]

| Council allowance category |

Mayoral allowance limit $ per annum(a) |

Councillor allowance range $ per annum(a)(b) |

|---|---|---|

| Category 1 | Up to 62,884 | 8,833 - 21,409 |

| Category 2 | Up to 81,204 | 10,914 - 26,245 |

| Category 3 | Up to 100,434 | 13,123 - 31,444 |

Notes: (a) Values do not include an additional amount equivalent to the Superannuation Guarantee contribution.

(b) Deputy Mayors are subject to the same allowance range as Councillors, for a given category.

Source: LGV, ‘Guide to Councils – How Councils Work: Acts and Regulations’, Know Your Council, https://knowyourcouncil.vic.gov.au/guide-to-councils/how-councils-work/….

Until the Tribunal’s Determination takes effect, a Council is required to set the value of its allowances (within the applicable Council allowance category range) within six months of a general local government election, or by 30 June following the election (whichever is later). A Council may also adjust the value of its allowances if the Council’s allowance category is changed by the Minister for Local Government.68

The 2019 LGI survey found that most Councillors and Mayors received an allowance at, or near, the top of the range for their allowance category.69

The 2019 LGI survey also suggested that a high proportion of respondents were dissatisfied with the value of the allowance received. Of those that responded:

- 44 per cent of Mayors and 59 per cent of Councillors agreed with the statement ‘I do not get paid enough’

- however, 50 per cent of Mayors and 27 per cent of Councillors agreed with the statement ‘I am paid an appropriate amount’.70

The remainder of respondents said they did not have an opinion on the matter, or that Councillor allowances were too high.71

Allowances for Melbourne City Council

Allowances for Melbourne City Council are currently set in an Order made by the Governor in Council. These allowances are set by reference to the level of allowances set for Category 3 Councils. As at June 2021, for Melbourne City Council:

- the Lord Mayor’s annual allowance of $200,870 is double the maximum annual allowance of a Category 3 Mayor

- the Deputy Lord Mayor’s annual allowance of $100,434 is equal to the maximum annual allowance of a Category 3 Mayor

- a Councillor’s annual allowance of $47,165 is equal to one-and-a-half times the maximum annual allowance of a Category 3 Councillor.72

Allowances for Greater Geelong City Council

Although Greater Geelong City Council is a Category 3 Council, allowances for the Mayor and Deputy Mayor are set in an Order made by the Governor in Council. As at June 2021, for Greater Geelong City Council:

- the Mayor’s annual allowance of $100,434 is equal to the maximum annual allowance of a Category 3 Mayor

- the Deputy Mayor’s annual allowance of $31,444 per annum is equal to the maximum annual allowance of a Category 3 Councillor.

Allowances for other Councillors in Greater Geelong City Council are set according to the same process which applies to other Category 3 Councils.

Trends in allowance values

From 2001 to 2007, there was no change to allowance limits and ranges. Allowance levels were increased by around 30 per cent following the 2008 Allowances Review. This change reflected increases applied to the remuneration of Victorian statutory and executive officers since 2000, and the finding of the 2008 Allowances Review that allowance levels presented a barrier to candidacy for women, young people and mid-career professionals.73

Since 2008, Council member allowances have been adjusted annually in line with the ‘annual adjustment guideline rate’ set by the Premier for public sector executives and board members in Victoria.74 For 2020-21, the annual adjustment rate was zero and no changes were made to allowances.

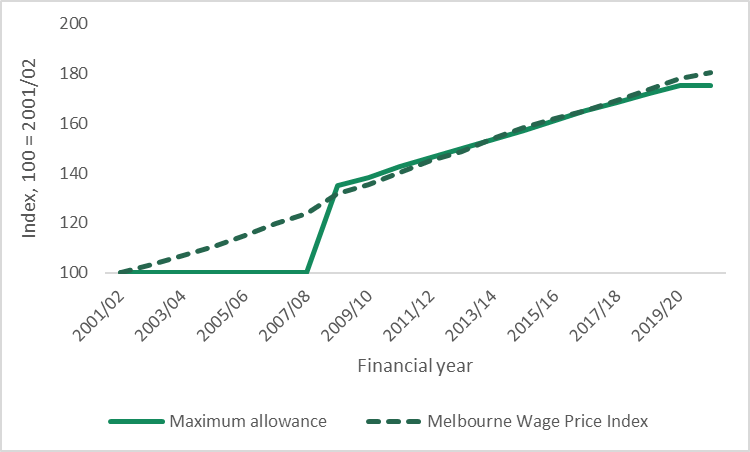

Figure 6 provides an example of how the maximum allowance payable to Councillors in a Category 1 Council has changed since 2001-02 and compares this to changes in the growth in the Melbourne Wage Price Index since that time.

Similar changes occurred to the maximum allowance payable to Councillors in categories 2 and 3 over the same period.

Superannuation arrangements

Superannuation arrangements for Council members are complex.

The Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992 (Cth) (SG Act) provides that employers must contribute a minimum amount to a complying superannuation fund on behalf of each eligible employee. SG contributions are expressed as a percentage of ordinary time earnings and are set at 10 per cent for 2021-22.

The SG Act excludes Mayors and Councillors across Australia from the definition of ‘employee’. This means that Councils would not ordinarily be required to pay the SG contribution to Council members. Section 12(9A) of the SG Act states that:

a person who holds office as a member of a local government council is not an employee of the council.

However, the Australian Taxation Office does allow Council members to re-direct their allowances to superannuation on a pre-tax basis if they wish to do so.75

In addition, each Council has the option to resolve to become an Eligible Local Governing Body (ELGB) under the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth).76 Where a Council has made such a resolution, Council members are considered to be employees for a variety of taxation purposes and for the purposes of the SG Act.77

Since 2008, an amount equivalent to the SG contribution is paid to Council members in those Councils that have not resolved to become ELGBs. This followed a recommendation of the 2008 Allowances Review which noted that:

For those who forgo income and/or employment to participate in local government the loss of superannuation has been identified as a significant issue. This can become a barrier to participation for both existing and potential Councillors.78

As a result of the factors above, the Tribunal understands that all Council members receive either an SG contribution or an amount equivalent to the SG contribution in addition to their allowance.

Remote Area Travel Allowance

A Remote Area Travel Allowance — paid as compensation for time spent on long‑distance travel — is available to eligible Council members.79

To be eligible, a Council member must normally reside more than 50km by the shortest practicable road distance from the location specified for Council meetings, or for municipal or community functions which the Council member has been authorised by Council to attend.

The Remote Area Travel Allowance is equal to $40 per day for authorised events that are attended, subject to an annual cap of $5,000 per Council member.80

Impact of allowance levels on Council member diversity

The Minister for Local Government’s letter to the Tribunal noted that:

The Tribunal may wish to consider the impact that allowances may have on representation in local leadership roles, especially in terms of the representation of women.

Past reviews have found that the value of the allowance payable to Council members can have a significant impact on an individual’s decision to stand for Council, with implications for diversity of representation. For example, the 2008 Allowances Review found allowance values presented a barrier to standing for election (and re-election) for certain groups. The 2008 Allowances Review reported that increasing the value of allowances would encourage women, young people and people from culturally - and linguistically diverse backgrounds, in particular, to nominate for election to Council.

Several Victorian Government initiatives aim to promote diversity in the local government sector.

Victorian Government initiatives to promote diversity in local government:

Gender equality initiatives

Setting a target of 50 per cent women Councillors and Mayors by 2025, as part of the Gender Equality Strategy.

- Forming a Gender Equality Advisory Committee to advise the Minister for Local Government and Minister for Women on how to deliver the 50 per cent target and improve gender equality across the sector, including through implementation of the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic).

Providing funding for the:

- ‘It’s Our Time’ campaign to promote and support women on councils

- Victorian Local Governance Association’s ‘Local Women Leading Change’ program

- Australian Local Government Women’s Association – Victoria to continue and expand its mentorship program, pairing 43 newly-elected female Councillors with experienced mentors from across the State.

Increased participation by Aboriginal communities

- Providing funding to encourage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to nominate as candidates in the 2020 local government elections.

Sources: Department of Premier and Cabinet, Safe and Strong, a Victorian Gender Equality Strategy, accessed 29 June 2021, https://www.vic.gov.au/our-gender-equality-strategy; LGV, ‘Gender Equality in Local Government’, accessed 29 June 2021, https://www.localgovernment.vic.gov.au/our-programs/gender-equity; Premier of Victoria, ‘Support for Next Generation of Women on Councils’, Premier of Victoria, media release, 11 March 2021.

In the local government elections in Victoria in 2020:

- the proportion of female Council members increased to over 43 per cent, representing the highest proportion of female Council members in Victoria’s history, and in any Australian jurisdiction

- at least 28 openly LGBTIQ+ candidates were elected to 20 Councils, an increase from 11 elected at the 2016 local government elections.81

References

- Victorian Councillor Allowances Review Panel, Review of the remuneration of mayors and councillors (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, June 2000).

- Local Government (Councillor Remuneration Review) Panel, Local Government (Councillor Remuneration Review) Panel Report (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, January 2008).

- VIRTIPS Act, s24(2)(a).

- State Government of Victoria, Recognition and Support, the Victorian Government’s Policy Statement on Local Government Mayoral and Councillor Allowances and Resources (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, April 2008), 1.

- LGI, Councillor expenses and allowances: equitable treatment and enhanced integrity (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, September 2020), 11. The other response options for this question were ‘It accounts for the opportunity cost of being a Councillor’, ‘I don’t have a strong view on the matter’ and ‘Other’.

- State Government of Victoria, Recognition and Support, the Victorian Government’s Policy Statement on Local Government Mayoral and Councillor Allowances and Resources (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, April 2008), 15.

- Victoria, Victorian Government Gazette, No. G 13, 29 March 2001, 556-558.

- Victorian Councillor Allowances Review Panel, Review of the remuneration of mayors and councillors (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, June 2000), 21.

- Victorian Councillor Allowances Review Panel, Review of the remuneration of mayors and councillors (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, June 2000), 22.

- State Government of Victoria, Recognition and Support, the Victorian Government’s Policy Statement on Local Government Mayoral and Councillor Allowances and Resources (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, April 2008), 11.

- LGV, ‘Guide to Councils – Councillor remuneration’, Know Your Council, accessed 2 March 2021, https://knowyourcouncil.vic.gov.au/guide-to-councils/how-councils-work/….

- Local Government Act 1989 (Vic), s74(1).

- LGI, Councillor expenses and allowances: equitable treatment and enhanced integrity (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, September 2020), 11.

- LGI, Councillor expenses and allowances: equitable treatment and enhanced integrity (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, September 2020), 11.

- LGI, Councillor expenses and allowances; equitable treatment and enhanced integrity (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, September 2020), 11. 179 Councillors and 38 Mayors responded to this question.

- Local Government Electoral Review Panel, Local Government Electoral Review Stage 2 Report, (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, July 2014), 79

- Local Government (Councillor Remuneration Review) Panel, Local Government (Councillor Remuneration Review) Panel Report (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, January 2008), 1.

- Tribunal’s analysis of Ministerial notices published in the Government Gazette which specified the rate of adjustment.

- Australian Taxation Office, ‘Interpretative Decision 2007/205 - Assessability of superannuation contributions made in favour of local government councillors’, 24 October 2007.

- Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth), s446-5(1)(a) and Schedule 1, 12-45(1)(e).

- Local Government (Councillor Remuneration Review) Panel, Local Government (Councillor Remuneration Review) Panel Report (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, January 2008), 20.

- State Government of Victoria, Recognition and Support, the Victorian Government’s Policy Statement on Local Government Mayoral and Councillor Allowances and Resources (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, April 2008), 14.

- Local Government (Councillor Remuneration Review) Panel, Local Government (Councillor Remuneration Review) Panel Report (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, January 2008), 14.

- Victoria, Victorian Government Gazette, No. G 27, 5 July 2012, 1489-1492.

- MAV, ‘News – Diversity on the up in Victorian councils’, Municipal Association of Victoria, accessed 21 April 2021, https://www.mav.asn.au/news/2020-news/diversity-on-the-up-in-victorian-….

Jurisdictional comparisons

In making the Determination, the Tribunal is required to consider similar allowances for elected members of local government bodies in other States.82 The Tribunal also proposes to consider allowances paid to Council members in the Northern Territory. The Australian Capital Territory does not have a separate system of local government.

In Australian states, an independent tribunal or commission generally sets the value of Council member allowances (as an exact amount or a range). The exception is Tasmania, where the values are set in regulations.

In the Northern Territory, allowance ranges are currently set in guidelines issued by the Minister for Local Government. However, legislative reforms made in 2019 gave the Northern Territory Remuneration Tribunal the power to set the maximum values of allowances.83

Each Australian jurisdiction groups Councils in allowance categories, and sets the value of allowances (or allowance ranges) differently for each group. The factors used to divide Councils into allowance categories vary between jurisdictions (table 4). For example:

- Councils in Tasmania are categorised based on revenue and population, in a way similar to Victoria

- New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia use a wider variety of factors to categorise Councils.

Table 4: Factors used to determine allowance categories for Councils across Australian jurisdictions

| Jurisdiction | Population Size | Revenue/ expenditure | Geography(a) | Extent of services provided | Infrastructure and assets | Growth potential/extent of development | Other factors(b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New South Wales | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Victoria | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Queensland | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| South Australia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Western Australia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Tasmania | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Northern Territory | Yes |

Notes: (a) Includes the size of a local government area and the spread or distribution of its population. (b) Includes social, economic and environmental factors.

Sources: Department of Housing, Local Government and Regional Services (NT), Discussion Paper: Elected Member Allowances (NT Government: Darwin, 2009); Local Government Act 1993 (NSW), s240(1); Local Government Act 1999 (SA), s76(3); Local Government Regulation 2012 (Qld), s242; State Government of Victoria, Recognition and Support, the Victorian Government’s Policy Statement on Local Government Mayoral and Councillor Allowances and Resources (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, 2008); Tasmanian Industrial Commission, Report into Councillor Allowances (Tasmanian Industrial Commission: Hobart, 2018), 17; Western Australia Salaries and Allowances Tribunal, Determination Under Section 7A of the Salaries and Allowances Act 1975 – Local Government Chief Executive Officers (Salaries and Allowances Tribunal: Perth, 2012), 8.

Australian jurisdictions generally apply different allowance arrangements to capital city Councils. For example, a capital city Council may be placed into its own allowance category, or its allowances may be set using a separate process. An exception is Tasmania, where the value of allowances for Hobart City and Launceston City Councils are the same.

Table 5 summarises the values of allowances in Councils (excluding capital cities) across Australian jurisdictions. For this group of Councils, Victoria’s maximum allowance for both Councillors and Mayors is the second lowest of all jurisdictions, after South Australia.

Table 6 summarises the values of allowances payable to capital city Council members across Australian jurisdictions. Broadly speaking, when comparing these allowances, Melbourne City Council falls somewhere in the middle of the range.

However, caution needs to be exercised when comparing Council member allowances across jurisdictions, given differences in Council roles and functions.84

Table 5: Jurisdictional comparison of Council allowances, excluding capital city Councils, June 2021

| Jurisdiction | Category | Mayor (or equivalent) | Value of allowances ($ per annum)(a) Deputy Mayor (or equivalent) | Councillors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New South Wales |

lowest highest |

18,970-38,690 57,590-144,450 |

N/A N/A |

9,190-12,160 18,430-34,140 |

| Victoria |

lowest highest |

up to 62,884 up to 100,434 |

N/A N/A |

8,833-21,049 13,123-31,444 |

| Queensland |

lowest highest |

108,222 258,066 |

62,435 178,981 |

54,110 154,006 |

|

South Australia(b)(c) |

lowest highest |

26,000 93,400 |

8.125 29,188 |

6,500 23,350 |

|

Western Australia(d) |

lowest highest |

2,308-35,902 75,862-137,269 |

1,923 - 15,576 37,419 - 54,116 |

1,795-10,550 24,604-31,678 |

| Tasmania |

lowest highest |

34,128 133,347 |

20,096 62,704 |

9,777 38,099 |

|

Northern Territory(e) |

lowest highest |

up to 35,383 up to 114,455 |

up to 14,661 up to 41,926 |

up to 12,907 up to 35,791 |

Notes: (a) Excludes County Councils established to perform specific functions. (b) Excludes a ‘travel time allowance’, which may be provided to a member of a non-metropolitan Council. (c) Presiding members of prescribed committees are entitled to an annual allowance of 1.5 times the Councillor allowance, while presiding members of committees which are not prescribed receive an additional amount of up to $1,680 per annum. (d) Councils may elect to pay Councillors a fee in respect of every meeting they attend, or provide an annual allowance in lieu of meeting fees. Values calculated on the basis of a Council opting for an annual allowance. Mayors and Deputy Mayors (or equivalent) are also entitled to an additional allowance on top of their attendance fees (whether paid annually or per meeting). (e) Values include a Base Allowance, Electoral Allowance, Professional Development Allowance, and the maximum extra meeting allowance.

Sources: Department of Local Government, Housing and Community Development (NT), Legislation, last updated 2 September 2020, https://dlghcd.nt.gov.au/publications-and-policies/local-government-leg…; Local Government (General) Regulations 2015 (Tas); Local Government Victoria; New South Wales Local Government Remuneration Tribunal, Annual Report and Determination, 2020; Queensland Local Government Remuneration Tribunal, Annual Report 2019, 2019; Remuneration Tribunal of South Australia, Allowances for Members of Local Government Councils, Determination No. 6 of 2018; Western Australia Salaries and Allowances Tribunal, Determination of the Salaries and Allowances Tribunal on Local Government Chief Executive Officers and Elected Members, 2020.

Table 6: Jurisdictional comparison of Council allowances, capital city Councils, June 2021

| Council | Mayor (or equivalent) | Value of allowances ($ per annum) Deputy Mayor (or equivalent) | Councillors |

|---|---|---|---|

| City of Sydney | 196,740 - 263,040 | N/A | 27,640 - 40,530 |

| Melbourne City Council | 200,870 | 100,434 | 47,165 |

| Brisbane City Council(b) | 365,316 | 299,538 | 160,938 |

| City of Adelaide | 177,000 | 38,895 | 25,930(c) |

| City of Perth (d) | 86,113 - 184,784 | 24,604 - 65,995 | 24,604 - 31,678 |

| City of Hobart | 133,347 | 62,704 | 38,099 |

| City of Darwin (e) | 161,897 | 58,284 | 49,517 |

Notes: (a) Depending on the jurisdiction, allowances are either specified as an exact amount (Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Hobart), a range (Sydney and Perth) or a maximum amount (Darwin). (b) The Lord Mayor and Deputy Lord Mayor of Brisbane City Council receive both a salary and an allowance, while Councillors only receive a salary. Values reflect both (but exclude superannuation entitlements). (c) Presiding members of prescribed committees are entitled to an annual allowance of 1.5 times the Councillor allowance, while presiding members of committees which are not prescribed receive an additional amount of up to $1,680 per annum. (d) Councils may elect to pay Councillors a fee in respect of every meeting they attend or provide an annual allowance in lieu of meeting fees. Values calculated on the basis of a Council opting for an annual allowance. Mayors and Deputy Mayors (or equivalent) are also entitled to an additional allowance on top of their attendance fees (whether paid annually or per meeting). (e) Figures are the maximum allowances payable, and include a Base Allowance, Electoral Allowance, Professional Development Allowance, and the maximum extra meeting allowance.

Sources: Brisbane Independent Council Remuneration Tribunal, Findings and Recommendations Report, 2019; Department of Local Government, Housing and Community Development (NT), Legislation, last updated 2 September 2020, https://dlghcd.nt.gov.au/publications-and-policies/local-government-leg…; Local Government (General) Regulations 2015 (Tas); Local Government Victoria; New South Wales Local Government Remuneration Tribunal, Annual Report and Determination, 2020; Remuneration Tribunal of South Australia, Allowances for Members of Adelaide City Council, Determination No. 7 of 2018; Western Australia Salaries and Allowances Tribunal, Determination of the Salaries and Allowances Tribunal on Local Government Chief Executive Officers and Elected Members, 2020.

References

- VIRTIPS Act, s23A(5)(a)).

- Local Government Act 2019 (NT), s106.

- Productivity Commission, Shifting the Dial: 5 Year Productivity Review, Supporting Paper No. 16, Local Government (Commonwealth Government of Australia: Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, 3 August 2017), 3-4.

Allowances for persons elected to other voluntary part-time community bodies

As well as considering similar allowances for elected members of local government bodies in other States, the Tribunal is required to consider allowances for persons elected to other ‘voluntary part-time community bodies’.85

In addition to the other matters identified, the Tribunal is also interested in receiving submissions about the types of bodies that could meet this definition.

References

- VIRTIPS Act, s23A(5)(a).

Economic and financial considerations

In making its Determination, the VIRTIPS Act requires that the Tribunal consider:

- current and projected economic conditions and trends (s24(2)(c))

- the financial position and fiscal strategy of the State of Victoria (s24(2)(b))

- any statement or policy issued by the Government of Victoria which is in force with respect to its Wages Policy (or equivalent) and the remuneration and allowances of any specified occupational group (s24(2)(a)).

Current economic and financial conditions and trends, and relevant Victorian Government policies, are set out below. In addition, the Tribunal proposes to consider the financial implications for Councils of setting different allowance values.

Current and projected economic conditions and trends

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data show that Australia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew by 1.8 per cent over the March quarter 2021, and by 1.1 per cent over the preceding 12 months. This followed consecutive quarters in which GDP growth exceeded 3 per cent — the first time this has occurred in the history of the National Accounts. As a result, GDP is now 0.8 per cent higher than its level before the COVID-19 pandemic.86

The Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) latest Statement on Monetary Policy (May 2021) noted that the Australian economy is continuing to recover strongly from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, and is:

… transitioning from recovery to the expansion phase earlier and with more momentum than expected.87

The RBA’s Statement observed that the recovery has been supported by favourable health outcomes, the removal of restrictions and substantial fiscal and monetary support, as well as stronger household spending, dwelling investment and exports. Nonetheless, the recovery is expected to be uneven as the COVID‑19 pandemic continues to weigh on some parts of the economy (e.g. tourism and educational service providers).88

In the RBA’s baseline scenario, GDP is expected to grow by 4.75 per cent over 2021 and 3.5 per cent over 2022. The baseline scenario assumes that:

- the domestic vaccine rollout accelerates in the second half of the year

- international borders are reopened gradually from early 2022

- there are no further large virus outbreaks and extended hard lockdowns, and any restrictions imposed are brief.89

ABS data show that the national unemployment rate has continued to fall, reaching 5.1 per cent in May 2021. This is the lowest the unemployment rate has been since February 2020.90

The RBA’s Statement forecast that the unemployment rate will continue to decrease, reaching 5 per cent by the end of 2021 and 4.75 per cent by mid-2022. This is expected to put some upward pressure on wages and inflation, which currently remains ‘subdued’ according to the RBA.91 The RBA expects the Australian Wage Price Index (WPI) to grow by a little under 2 per cent over 2021, with growth to increase to around 2.25 per cent by mid-2023. Meanwhile, underlying inflation is expected to increase gradually to 1.75 per cent by mid‑2022.92

According to the RBA Governor, Dr Philip Lowe:

The [RBA] Board wants to see the recent recovery transition into strong and durable economic growth, with low unemployment and faster growth in wages than we have seen recently.93

Victoria’s Gross State Product (GSP) fell by 0.5 per cent during the 2019‑20 financial year, as economic activity was curtailed due to lockdown measures.94 However, recent data suggest that Victoria’s economy has begun to recover. State Final Demand95 grew by just under 10 per cent in the 6 months to March 2021, the highest growth rate of all states and territories. This was driven by a 15 per cent increase in household consumption following the easing of public health-related restrictions.96

The Victorian Budget 2021/22 (Victorian Budget), released in May 2021, reported the following economic outlook for Victoria:97

- real GSP is estimated to have contracted by two per cent in 2020‑21 (down from the previous Budget’s forecast of four per cent) and is forecast to grow by 6.5 per cent in 2021-22

- the unemployment rate is expected to average 5.75 per cent in 2021‑22, before reaching 5.25 per cent in 2023‑24.

Regarding price movements, ABS data show that the All Groups Consumer Price Index (CPI) for Melbourne grew by 0.8 per cent between March 2020 and March 2021, the lowest growth rate of all capital cities.98 Meanwhile, the Victorian Budget forecast annual growth in CPI for Melbourne to increase to above two per cent by 2024‑25.99

Regarding wage movements, ABS data show that the Victorian WPI increased by 1.5 per cent for the 12 months to March 2021.100 The Victorian Budget forecast annual growth in the Victorian WPI to increase to 2.5 per cent by 2024‑25.101

Another commonly used measure of wage movements, full-time average weekly ordinary time earnings (AWOTE) of Victorian adults, grew by around 4.4 per cent between November 2019 and November 2020.102

Victoria’s financial position and fiscal strategy

The Tribunal is required to consider the financial position and fiscal strategy of the State of Victoria (s24(2)(b) of the VIRTIPS Act).

Victorian Auditor-General’s Office financial report

The Victorian Auditor-General’s Office (VAGO) financial report on the State of Victoria, released in November 2020, noted that the COVID-19 pandemic had:

…. necessitated a significant reset in the state’s revenue and expenditure policies… [with] significant unexpected falls in revenue and increases in expenditure, and consequently debt.103

Victorian Budget

The Victorian Budget forecast an operating deficit (for the general government sector) of approximately $11.6 billion for 2021‑22, with smaller deficits expected in the following years. Meanwhile, net debt is forecast to be $102.1 billion (20.3 per cent of GSP) in 2021-22 and to increase to $156.3 billion (26.8 per cent of GSP) in 2024-25. These forecasts reflect an improvement relative to the previous Budget, which the Victorian Budget stated is principally due to improvements in the Victorian Government’s operating position.104

The Victorian Budget noted that uncertainty around Victoria’s revenue outlook remains elevated due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, deviation from forecasting assumptions — which include that further domestic outbreaks of COVID-19 are contained and result only in localised, short-term restrictions — would weigh on the revenue outlook over the Budget and forward estimates.105 The Victorian Budget also outlined the Victorian Government’s four-step fiscal strategy:

- step 1: creating jobs, reducing unemployment and restoring economic growth

- step 2: returning to an operating cash surplus

- step 3: returning to operating surpluses

- step 4: stabilising debt levels.

The Victorian Budget includes significant infrastructure spending to support economic recovery, with annual Government infrastructure investment expected to average $22.5 billion over the Budget and forward estimates.106

The Victorian Government has also outlined several efficiency measures for departments, and the broader public sector, as part of its strategy to return to an operating surplus in the medium term. In particular:

- indexation of departments’ base funding will be revised, with different rates to apply to wage and non-wage components107

- from 1 January 2022, guaranteed annual wage increases for non-executive public sector employees will be reduced from two per cent to 1.5 per cent through the Victorian Government’s Wages Policy.108

Victorian Government Wages Policy

The Tribunal is required to consider any statement or policy issued by the Government of Victoria that is in force with respect to its Wages Policy (or equivalent) and the remuneration and allowances of any specified occupational group (s24(2)(a) of the VIRTIPS Act).

Box 3 reproduces the Victorian Government Wages Policy and the Enterprise Bargaining Framework (Wages Policy) which applies to employees in the Victorian public sector.

Victorian Government Wages Policy and the Enterprise Bargaining Framework

The Victorian Government Wages Policy and the Enterprise Bargaining Framework has three pillars:

A ‘Secondary Pathway’ is also available for public sector agencies whose current enterprise agreement reaches its nominal expiry date on or before 30 June 2020 which permits one annual wage and allowance increase capped at 2.5 per cent (instead of at 2 per cent). |

Source: Industrial Relations Victoria, ‘Victorian Government Wages Policy,’ Wages Policy and the Enterprise Bargaining Framework (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, 2019).

Victorian Government Wages Policy from 2022

The Victorian Government has announced changes to the Wages Policy that will apply from 1 January 2022. From that date:

- the annual cap on wages and conditions, under Pillar 1 of the Wages Policy, will be adjusted from 2 per cent to 1.5 per cent

- additional changes to allowances and other conditions (not general wages) under Pillar 3 of the Wages Policy will be capped at 0.5 per cent of the salary base per annum

- a limited one-year rollover option with a 2 per cent increase will be available for parties whose current enterprise agreements reach their nominal expiry date in 2022.109

Financial impacts of varying allowance levels

The Tribunal also seeks submissions on the financial impacts of any proposed changes to allowance levels for Council members.

Council operations are primarily funded through rates and charges and government grants and contributions. Councils use these funds to provide services for their communities and to renew and maintain infrastructure assets.110 These funds are also used to pay Council wages and Council member allowances.

The Results of 2019-20 Audits: Local Government, published by VAGO, stated that the local government sector remained resilient over the short term. However, it also noted that the COVID-19 pandemic affected the sector’s financial performance in 2019-20, and was expected to have a greater impact on the sector’s performance during 2020-21.111

In 2015, the Victorian Government introduced the Fair Go Rates System, also referred to as ‘rate capping’. Under the Fair Go Rates System, the Minister for Local Government may make an Order setting a maximum increase in the average rates bill that Councils can charge each year. Councils can apply to the Essential Services Commission for an exemption to the rate cap.112 The Fair Go Rates System may limit the capacity of some Councils to raise additional revenue to address increases in required expenditure (for example, if they are required to pay Council members a higher allowance).113 However, the rate cap does not prevent a Council from increasing expenditure in one part of its budget by re-allocating funds from another.

References

- ABS, Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product, March 2021.

- RBA, Statement on Monetary Policy – May 2021 (Reserve Bank of Australia: Sydney, NSW, February 2021), 71.

- RBA, Statement on Monetary Policy – May 2021, 1, 29, 71.

- RBA, Statement on Monetary Policy – May 2021, 71.

- ABS, Labour Force, Australia, May 2021.

- RBA, Statement on Monetary Policy – May 2021, 71.

- RBA, Statement on Monetary Policy – May 2021, 71, 77.

- Phillip Lowe, From Recovery to Expansion, keynote address at the Australian Farm Institute Conference, Toowoomba, 17 June 2021.

- ABS, Australian National Accounts: State Accounts, 2019-20.

- Defined by the ABS as a measure of the total value of goods and services sold in the state to buyers who wish to either consume them or retain them in the form of capital assets.

- ABS, Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product, March 2021.

- DTF, Victorian Budget 2021/22 - Overview (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, May 2021), 4.

- ABS, Consumer Price Index, Australia, cat. no. 6401.0, March 2021.

- DTF, Victorian Budget 2021/22 - Overview, 4.

- ABS, Wage Price Index, Australia, cat. no. 6345.0, March 2021.

- DTF, Victorian Budget 2021/22 - Overview, 4.

- ABS, Average Weekly Earnings, Australia, cat no. 6302.0, November 2020.

- VAGO, Auditor-General’s Report on the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria: 2019-20 (Victorian Auditor-General's Office: Melbourne, November 2020), 1.

- DTF, Victorian Budget 2021/22 – Budget Paper No. 2: Strategy and Outlook (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, May 2021), 6.

- DTF, Victorian Budget 2021/22 – Budget Paper No. 5: Statement of Finances (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, May 2021), 166.

- DTF, Victorian Budget 2021/22 – Budget Paper No. 2, 6.

- DTF, Victorian Budget 2021/22 – Budget Paper No. 2, 6.

- Victorian Government, ‘Contributing a Fair Share for a Stronger Victoria’, media release, 15 May 2021, https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/contributing-fair-share-stronger-victoria.

- Industrial Relations Victoria, ‘Victorian Government Wages Policy,’ Wages Policy and the Enterprise Bargaining Framework (State Government of Victoria: Melbourne, Victoria, 2021).

- VAGO, Results of 2019-20 Audits: Local Government (Victorian Government Printer: Melbourne, Victoria, March 2021), 5-6.

- VAGO, Results of 2019-20 Audits: Local Government (Victorian Government Printer: Melbourne, Victoria, March 2021), 20.

- Parliament of Victoria, Final report of the inquiry into the sustainability and operational challenges of Victoria’s rural and regional councils (Victorian Government Printer: Melbourne, Victoria, March 2018), 292; Local Government Act 1989 (Vic), ss185D and 185E.

- Under the Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), Council members are entitled to receive an allowance from their Council in accordance with the Tribunal’s Determination.

Summary

The Tribunal is required to make a Determination setting the values of allowances for Mayors, Deputy Mayors and Councillors. The Determination must also provide for Council allowance categories.

This Consultation Paper outlines some matters for consideration in making the Determination in order to help facilitate submissions from interested persons and bodies to the Tribunal about the terms of the Determination.

Submissions close on Monday 16 August 2021 and will be published on the Tribunal’s website, unless the person or body making the submission indicates that the submission is confidential, or unless the submission contains information that is identified as commercially sensitive. In these instances, submissions will be published in a form which protects confidentiality or commercial sensitivity. Submissions that contain offensive or defamatory comments, or which are outside the scope of the Determination, will not be published.

Appendix A: Victorian Councils by existing allowance category

| Category 1 | Category 2 | Category 3 |

|---|---|---|

|

Alpine Shire Council Ararat Rural City Council Benalla Rural City Council Borough of Queenscliffe Buloke Shire Council Central Goldfields Shire Council Corangamite Shire Council Gannawarra Shire Council Hepburn Shire Council Hindmarsh Shire Council Indigo Shire Council Loddon Shire Council Mansfield Shire Council Mount Alexander Shire Council Murrindindi Shire Council Northern Grampians Shire Council Pyrenees Shire Council Southern Grampians Shire Council Strathbogie Shire Council Towong Shire Council West Wimmera Shire Council Yarriambiack Shire Council

|

Bass Coast Shire Council Baw Baw Shire Council Bayside City Council Campaspe Shire Council Colac Otway Shire Council East Gippsland Shire Council Glenelg Shire Council Golden Plains Shire Council Greater Shepparton City Council Hobsons Bay City Council Horsham Rural City Council Latrobe City Council Macedon Ranges Shire Council Maribyrnong City Council Maroondah City Council Mildura Rural City Council Mitchell Shire Council Moira Shire Council Moorabool Shire Council Moyne Shire Council Nillumbik Shire Council South Gippsland Shire Council Surf Coast Shire Council Swan Hill Rural City Council Wangaratta Rural City Council Warrnambool City Council Wellington Shire Council Wodonga City Council Yarra City Council |

Ballarat City Council Banyule City Council Boroondara City Council Brimbank City Council Cardinia Shire Council Casey City Council Darebin City Council Glen Eira City Council Frankston City Council Greater Bendigo City Council Greater Dandenong City Council Greater Geelong City Council Hume City Council Kingston City Council Knox City Council Manningham City Council Melton Shire Council Monash City Council Moreland City Council Moonee Valley City Council Mornington Peninsula Shire Council Port Phillip City Council Stonnington City Council Whitehorse City Council Whittlesea City Council Wyndham City Council Yarra Ranges Shire Council

|

Note: Melbourne City Council does not have an allowance category.

Source: Local Government Victoria, ‘Guide to Councils – Councillor remuneration’, Know Your Council, accessed 2 March 2021, https://knowyourcouncil.vic.gov.au/guide-to-councils/how-councils-work/the-system-of-government.

Abbreviations and glossary

| Term or abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|

| 2000 Allowances Review | Victorian Councillor Allowances Review Panel (2000), Review of the remuneration of mayors and councillors. |

| 2008 Allowances Review | Local Government (Councillor Remuneration Review) Panel (2008), Local Government (Councillor Remuneration Review) Panel Report. |

| 2008 Policy Statement | State Government of Victoria (2008), Recognition and Support, the Victorian Government’s Policy Statement on Local Government Mayoral and Councillor Allowances and Resources. |

| ABS | Australian Bureau of Statistics |

| AWOTE | Average Weekly Ordinary Time Earnings |

| CEO | Chief Executive Officer |

| CPI | Consumer Price Index |

| DTF | Department of Treasury and Finance |

| ELGB | Eligible Local Governing Body |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GSP | Gross State Product |

| LGBTIQ+ | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and gender diverse, Intersex, Queer and questioning |

| LGI | Local Government Inspectorate |

| 2019 LGI survey | Local Government Inspectorate (2020), Councillor expenses and allowances: equitable treatment and enhanced integrity. |

| LGV | Local Government Victoria |

| MAV | Municipal Association of Victoria |

| MAV Councillor census | Municipal Association of Victoria (2018), MAV Councillor Census. |

| Municipal district | The district for which a Council provides local government services. |

| p.a. | per annum |

| RBA | Reserve Bank of Australia |

| SG Act | Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992 (Cth) |

| Tribunal | Victorian Independent Remuneration Tribunal |

| VAGO | Victorian Auditor General’s Office |

| Victorian Budget | Victorian Budget 2021/22 |

| VIRTIPS Act | Victorian Independent Remuneration Tribunal and Improving Parliamentary Standards Act 2019 (Vic) |

| VLGA | Victorian Local Governance Association |